Paternal Contributions to Biopsychosocial Outcomes of Children With Cancer: A Scoping Review

Abstract

Though children with cancer experience better outcomes with supportive caregivers and family environments, these findings are predominantly informed by maternal perspectives. Given fathers’ increasing involvement, this scoping review examined paternal contributions to the biopsychosocial outcomes of their children with cancer. English, full-text publications from any time before October 4, 2022 including at least one search term from these three groups were included: pediatric oncology diagnosis ≤18 years old, fathers/parents, child biopsychosocial outcomes. Title and abstract screening, full-text reviews, data extraction, and quality assessments were completed by at least two reviewers. Results are presented using Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses Extension for Scoping Review guidelines. Of 10,116 studies screened, 29 were included. Most studies were poor (38%) or fair (45%) quality. Seventy-six percent presented significant associations between father contributions and child biopsychosocial outcomes, including child mental state, coping, behavioral adjustment, relationship quality in adulthood, and adherence. Fathers’ contributions were ambiguously related to children's quality of life and physical wellbeing. Limited findings suggest fathers contribute in significant, positive ways to their child with cancer's biopsychosocial outcomes. Findings underscore research gaps and suggest greater efforts should be made to include fathers in pediatric oncology research, interventions, and clinical practice.

Abbreviations

-

- QOL

-

- quality of life

1 Introduction

Annually, more than 400,000 children are diagnosed with cancer worldwide [1, 2]. Children with cancer experience better outcomes (e.g., better coping, quality of life [QOL]) with supportive caregivers (e.g., parents, step-parents, grandparents) and family environments (e.g., better family functioning, support, cohesion) [3-5]. Thus, a psychosocial standard of care for children with cancer emphasizes interventions to support parent, child, and family wellbeing [6-9]. Currently utilized interventions have low father involvement [10, 11]. In part, this may be because these interventions have primarily been developed using mother-informed research, inhibiting tailoring for fathers [3, 4]. This is a significant gap in empirical knowledge and intervention approaches, as fathers are more involved in and consequential to their children's development than ever before [12-15].

A recent systematic review examined the impact of fathers’ involvement on child biopsychosocial outcomes within pediatric chronic illness populations (e.g., asthma, diabetes) and found better father–child relationship quality was associated with better child outcomes (e.g., treatment adherence, illness management self-efficacy) [16]. However, no pediatric oncology studies were included. A review of fathers’ pediatric cancer stressors confirmed fathers’ unique, gendered experiences and support needs, but did not evaluate associations with child outcomes [4]. Recent reviews highlight the critical role of parent and family functioning in outcomes for children with cancer, including effects on family functioning [5], child adjustment [3], QOL [17], and mutual distress between parents and children [18]. However, fathers represented only a small fraction of the parents in these reviews, and none analyzed father-specific effects.

Therefore, we aimed to investigate fathers’ contributions to their child with cancer's biopsychosocial outcomes, defined as biological/physical, psychological, and social factors relevant to health [19]. Given the numerous biopsychosocial outcomes important to a child's wellbeing during treatment and survivorship [10, 20–27], these outcomes were broadly defined. This scoping review highlights current knowledge, research gaps, and ways to better integrate fathers into biopsychosocial pediatric oncology research.

2 Methods

Due to the limited, diverse nature of father-specific data in pediatric oncology, a scoping review was conducted to provide a comprehensive overview and identify literature gaps [16]. This approach allowed flexibility in capturing and characterizing the breadth of evidence on fathers' influences on their children's biopsychosocial outcomes [28]. The protocol was preregistered: https://doi.org/10.17605/OSF.IO/6MYCZ [29].

2.1 Information Sources

The research librarian (EL) generated a search strategy and terms around three main concepts (i.e., pediatric oncology, fathers/parents, child biopsychosocial outcomes), verified by authors AO and MS. An initial Medline search was conducted to identify keywords and index terms. The search strategy was adapted for Ovid Medline, Embase, APA PsycINFO, and Cochrane Central (File S1). The searches were completed on October 4, 2022. Files were imported into Covidence [30].

2.2 Inclusion Criteria

All texts mentioning fathers’ contributions to child biopsychosocial outcomes within pediatric oncology published at any time were included. Studies were included if: (i) they examined fathers/male caregivers with children who were diagnosed with cancer ≤18 years; (ii) a father's role/contribution was assessed and linked to their child with cancer's biopsychosocial outcome(s); and (iii) were English. Father roles/contributions were inclusive of psychosocial characteristics (e.g., mental health, coping behaviors), and child-related variables (e.g., parenting, involvement, relationship quality). Retrospective studies examining pediatric cancer survivors’ perspectives regarding their fathers’ contributions were included.

Studies were excluded if (i) they focused exclusively on fathers’ experiences; or (ii) did not differentiate between maternal and paternal effects.

2.3 Data Analysis

Using Covidence [30], titles, abstracts, and full-texts of selected citations were screened by two authors (AO, AB) against the inclusion criteria. Disagreements were resolved through discussion and/or with another author (MS). The data extraction tool was developed by three authors (AO, AB, MS; Table S1). All studies were extracted by at least two reviewers (AO, AB, BF, MS) who reached consensus for the final extracted information. Results are presented according to the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses extension for scoping review [31]. To consolidate heterogeneous child outcomes and father contributions for the purpose of discussion, we grouped categories of outcomes, including mental state, behavioral adjustment, physical wellbeing, and involvement. Full definitions can be found in the results and Table 1. Findings are organized by child biopsychosocial outcomes.

|

Number of studies (%) Citations |

Child mental statea | Child coping | Child behavioral adjustmentb | Child physical wellbeingc | Child quality of life | Child treatment adherence | Child relationship quality in adulthood | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Number of studies (%) Citations |

29 (100%) |

16 (55%) |

4 (14%) |

4 (14%) |

4 (14%) |

3 (10%) |

2 (7%) |

2 (7%) |

| Fathers’ mental statea |

16 (55%) |

11 (38%) |

1 (3%) [55] |

4 (14%) |

1 (3%) [48] |

3 (10%) |

— | — |

| Fathers’ involvementd |

8 (28%) |

4 (14%) |

1 (3%) [49] |

— |

2 (7%) |

1 (3%) [52] |

1 (3%) [56] |

1 (3%) [39] |

| Fathers’ coping |

6 (21%) |

2 (7%) |

3 (10%) |

1 (3%) [59] |

— | — | — | — |

| Fathers’ parenting stress |

3 (10%) |

2 (7%) |

— |

2 (7%) |

1 (3%) [48] |

1 (3%) [48] |

— | — |

| Father–child relationship quality |

3 (10%) |

1 (3%) [58] |

— | — | — | — | — |

2 (7%) |

| Fathers’ personality |

1 (3%) [40] |

— | — | — | — | — |

1 (3%) [40] |

— |

| Fathers’ communication |

1 (3%) [60] |

1 (3%) [60] |

— | — | — | — | — | — |

| Fathers’ satisfaction with caloric intake |

1 (3%) [38] |

— | — | — |

1 (3%) [38] |

— | — | — |

- Note: Rows and columns may not add to 29 as some studies presented multiple father contributions or child outcomes.

- a Mental state encompasses distress, anxiety, depression, psychopathology, negative mood, emotional problems, emotional state, internalizing symptoms, post-traumatic stress disorder, hopelessness.

- b Behavioral adjustment encompasses behavioral problems and externalizing behaviors.

- c Physical wellbeing encompasses physical activity, physical functioning, physical symptoms, and body mass index.

- d Involvement encompasses encouragement of physical activity, presence during medical procedures, participation in the study, being the primary caregiver, withdrawal from interaction with their ill child.

2.4 Quality Assessment

The Quality Assessment Tool for Observational Cohort and Cross-Sectional Studies evaluated the quality of quantitative studies [32]. For one qualitative study [33], we used the Rapid Critical Appraisal Tools for a Qualitative or Mixed-Methods Study [34]. One case report study [35] was evaluated using Rapid Critical Appraisal Questions for Case Studies [34]. Two authors (AO, AB) completed quality assessments of overall study quality: poor, fair, or good (Table 1).

3 Results

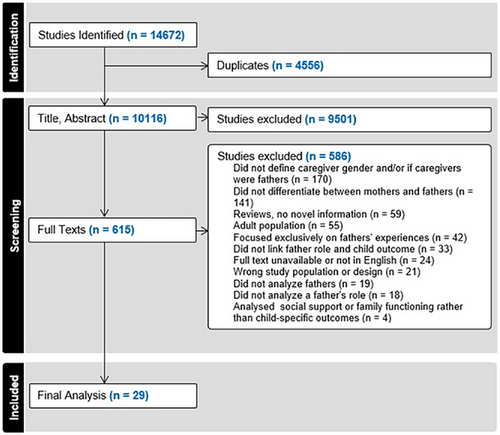

In total, 10,116 studies were screened (Figure 1). Title and abstract screening eliminated 9501 studies (e.g., mothers only, not pediatric cancer). Full-text review was conducted on 615 studies, with 586 excluded. Common exclusion reasons were undefined caregiver gender/role (e.g., father, mother, grandparent; n = 170; 29% of excluded full-texts) or lack of differentiation between mothers and fathers (n = 141; 24% of excluded full-texts).

Twenty-nine studies published between 1982 and 2022 were included. Full extracted data are given in Table S1. Sixteen studies were quantitative cross-sectional studies [36-51], nine quantitative longitudinal studies [52-60], and one each of the following: longitudinal randomized control trial [61], mixed method longitudinal study [62], qualitative study [33], and case report [35]. Quality assessments revealed most studies were fair (n = 13, 45%) [36–39, 41, 45, 46, 48, 51, 54, 57, 58, 60] or poor (n = 11; 38%) [35, 40, 42–44, 49, 50, 53, 56, 59, 61] quality; however five studies were “good” quality (17%) [33, 47, 52, 55, 62]. As scoping reviews are meant to summarize evidence regardless of methodological quality or risk of bias [31], no studies were excluded due to quality ratings.

Of 29 included studies, 17 (59%) were conducted in the United States [36–38, 40, 41, 44, 45, 47, 48, 50, 53-56, 58, 60, 61], three (10%) in Canada [35, 49, 52], and two (7%) in the United Kingdom [39, 59]. The remaining seven studies [33, 42, 43, 46, 51, 57, 62] represented seven different, high-income countries according to the World Bank Income Classification [63]. Study populations included children who were newly (i.e., less than 6 months) diagnosed or relapsed with cancer (n = 9, 31%) [37, 43, 51, 52, 55, 57, 60-62], receiving treatment for cancer (n = 7 studies, 24%) [35, 38, 40, 47–49, 56], cancer survivors (n = 10 studies, 35%) [33, 36, 39, 41, 42, 46, 50, 53, 58, 59], or involved based on time since cancer diagnosis and/or follow-up (n = 3 studies, 10%) [44, 45, 54]. All studies included both fathers and mothers. Excluding counts for eight studies where the number of fathers was unavailable [53, 57, 59, 61] or non-exact (see Table 1) [41, 45, 60, 64], there are 972 fathers and 1611 mothers of children with cancer from 21 studies [33, 35-40, 42-44, 46-48, 50-52, 54-56, 58, 62]. Only one study included more fathers of children with cancer than mothers [40], while three included equal numbers [35, 37, 44].

Across all studies, there was little consistency in fathers’ contributions and child biopsychosocial outcomes (Table 1), indicating a dearth of empirical evidence regarding fathers’ contributions to children with cancer's biopsychosocial outcomes. Most studies (76%, n = 22) presented significant associations between father contributions and child outcomes [36–42, 44, 45, 47–49, 51, 52, 54–56, 58–62], but some (17%, n = 5) presented only null associations [43, 46, 50, 53, 57]. Most studies evaluated child biopsychosocial outcomes via child self-reports (52%; n = 15) [36, 37, 39, 41, 42, 45-48, 50, 53, 55, 56, 58, 62], followed by parent proxy reports (34%; n = 10) [33, 38, 44, 48, 51, 52, 57-60], healthcare team perceptions and/or medical records (14%; n = 4) [35, 38, 54, 61], observational assessments (7%; n = 2) [49, 56], family interview (7%; n = 2) [35, 43], teacher reports (3%; n = 1) [59], or biological sample (3%; n = 1) [40].

3.1 Child Mental State

Sixteen studies (55%) [35–37, 43–50, 53, 56–58, 60] evaluated child mental state. Mental state encompassed distress, anxiety, depression, psychopathology, negative mood, emotional problems, emotional state, internalizing symptoms, post-traumatic stress disorder, and hopelessness. Ten of these studies found at least one significant association between child mental state and father's role [36, 37, 44, 45, 47–49, 56, 58, 60], and five found null associations [43, 46, 50, 53, 57]. Notably, most (80%; n = 8) of the studies identifying significant associations were published during or after 2007, whereas most (80%; n = 4) of the studies with null associations were published before 1999. Five studies examined child mental state in association with multiple fathers’ contributions (e.g., mental state, involvement, coping) [37, 44, 45, 48, 58]. Studies ranged from newly diagnosed through survivorship. Overall, significant associations suggested child mental states benefited from fathers’ contributions [36, 37, 44, 45, 47–49, 56, 58, 60].

3.1.1 Fathers’ Mental State

Child mental states were most often examined in conjunction with father mental states (n = 11 studies; 38%) [36, 37, 43–48, 50, 57, 58]. Over half of these studies (n = 6; 21%) [36, 37, 44, 45, 47, 58] identified significant associations between worse child mental states and worse father mental states. For example, Barakat et al. (1997) found that higher post-traumatic stress in children was associated with higher post-traumatic stress in fathers, and both Schepers et al. (2019) and Blotcky et al. (1985) found a significant link between worse child mental state and paternal distress. However, five studies [43, 46, 48, 50, 57] of child and father mental states did not identify significant correlations, indicating a lack of consensus regarding the nature of associations between child and father mental states.

3.1.2 Fathers’ Involvement

Child mental state was also examined in association with fathers’ involvement (n = 4 studies; 14%) [35, 45, 49, 56]. Fathers’ involvement was defined as: fathers as primary caregivers or study participants, fathers’ presence during medical procedures, fathers’ withdrawal from interacting with their child, or fathers’ encouragement of child physical activity. Three studies, primarily of children receiving treatment, identified that child mental state was benefitted by fathers’ involvement [45, 49, 56]. However, one case report suggested the child's emotional state was hindered due to the father withdrawing from the child and family [35]. Overall, results suggest child mental states are better when fathers are involved.

3.1.3 Other Father Contributions

Child mental states were also examined with four additional father contributions: parenting stress [48, 53], coping [37, 44], father–child relationship quality [58], and openness in father–child communication [60]. Two studies examined associations between child's mental states and father's parenting stress; one study of childhood cancer survivors found no significant associations [53], whereas Roddenberry and Renk (2008) found that more negative child mental states during treatment were significantly associated with greater paternal parenting stress [48]. In newly diagnosed children, better mental state was significantly associated with better father coping [37], yet was unrelated in another study of children 4 months or more post-diagnosis [44]. Finally, significant associations were identified between a more positive child mental state and more positive father–child relationship quality in childhood cancer survivors [58], as well as more openness in father–child communication among children newly diagnosed [60].

3.2 Child Coping

Four studies (14%) [49, 54, 55, 61] examined child coping. Three studies examined child coping with father coping, and found higher quality child and father coping were significantly linked [54, 55, 61], both near diagnosis [55, 61] and at 2 years post-diagnosis [54]. Additionally, Monti et al. (2017) found children engaged in less secondary control coping 14 months post-diagnosis when their fathers reported worse mental states 2 months post-diagnosis [55]. Lastly, children on treatment had significantly higher quality coping when fathers were involved [49]. Overall, studies suggested children had better coping in the context of better father coping, mental state, and involvement.

3.3 Child Behavioral Adjustment

Child behavioral adjustment (e.g., behavioral problems, externalizing behaviors) was examined in four studies (14%) [48, 51, 57, 59] evaluating associations between child behavioral adjustment and fathers’ mental state. Three studies, representing children newly diagnosed with cancer, on treatment, and in survivorship, found less optimal child behavioral adjustment was significantly associated with more negative father mental states [48, 51, 59]. However, one study of children on treatment only found this association was true for associations between fathers’ reports of child behavioral adjustment and fathers’ depression, whereas this association was nonsignificant for child and mother reports of child behavioral adjustment [48]. This aligns with the fourth study of children newly diagnosed, which found no association between child behavioral adjustment, as reported by mothers, and father's mental state [57]. Additionally, two studies of children newly diagnosed and on treatment reported a significant association between more negative child behavioral adjustment and higher paternal parenting stress [48, 51]. Finally, one study of survivors identified that more child behavioral problems were associated with more negative paternal coping strategies [59]. Overall, most studies indicate children have better behavioral adjustment when their father reports a better mental state, lower parenting stress, and less negative coping strategies.

3.4 Child Physical Wellbeing

Child physical wellbeing included physical activity, physical functioning, physical symptoms, and body mass index. Four studies (14%) [33, 38, 42, 48] examined child physical wellbeing. Two studies of childhood cancer survivors linked child physical wellbeing to fathers’ involvement; one qualitative study suggested children engaged in more physical activity when fathers were more involved and/or supportive [33], whereas a cross-sectional quantitative study found poorer child physical wellbeing was significantly associated with having a father as the primary caregiver [42]. Additionally, one study of children on treatment identified differing correlates of child physical symptoms based on child, father, and mother report of child physical symptoms in consistent, unexpected directions; for father reports, greater symptoms were associated with lower levels of fathers’ depression, anxiety, and parenting stress [48]. However, child self-reports were only associated with lower levels of fathers’ parenting stress, and mothers’ proxy reports were only associated with lower levels of fathers’ depression [48]. Finally, better child physical wellbeing on treatment was correlated with fathers’ greater satisfaction with their child's daily caloric intake [38]. Overall, associations ranged from positive to ambiguous.

3.5 Child QOL

Three studies (10%) [48, 52, 62] investigated child QOL. One study of newly diagnosed children indicated higher QOL in children was significantly associated with more negative paternal mental states [62]; however, two studies found significant associations between lower child QOL and more negative paternal mental states [48, 52]. Among these two studies [48, 52], one reported children newly diagnosed had lower QOL when a father, opposed to a mother, was the study participant [52]. No association between child QOL during treatment and fathers’ parenting stress was identified [48]. Overall, associations were ambiguous.

3.6 Child Treatment Adherence

Two studies (7%) [40, 56] of children on treatment examined child treatment adherence. Peterson (2013) found children had better treatment adherence during medical procedures when their fathers were involved versus their mothers [56], while Lansky et al. (1983) found children had greater adherence based on fathers’ personality characteristics; fathers of adherent females were avoidant of problems, whereas fathers of adherent males were hostile, concerned about their sons, under stress, responsive to external direction, and able to directly confront their problems [40]. Overall, child treatment adherence was positively associated with father contributions.

3.7 Child Relationship Quality in Adulthood

Child relationship quality in adulthood was investigated in two studies of childhood cancer survivors (7%) [39, 41]; both identified significant associations between better child close relationship quality in adulthood and positive father–child relationship quality [39, 41]. Additionally, children also had better relationship quality in adulthood when fathers were more involved (i.e., encouraging, influential) [39]. Overall, child relationship quality in adulthood benefited from father contributions.

4 Discussion

Research on how fathers influence the biopsychosocial outcomes of children with cancer is limited and varied, with only 29 studies meeting inclusion criteria, most of poor or fair quality. Fathers were underrepresented compared to mothers. Yet, findings suggest fathers may contribute in significant, largely positive ways to their child with cancer's mental state, coping, behavioral adjustment, relationship quality in adulthood, and treatment adherence, which are all important for children's wellbeing during treatment and survivorship [10, 20–27]. These findings suggest supporting fathers’ contributions (e.g., mental state, coping, father–child relationship quality, involvement) may ultimately improve outcomes for children with cancer. An equally important finding related to excluded studies, over 50% were excluded due to a lack of identification or analytically differentiating caregiver gender/type (e.g., father, grandparent, etc.). Findings underscore the importance of clear, consistent reporting of caregiver demographics, and suggest a potentially significant, positive role for fathers in the biopsychosocial outcomes of their children with cancer, though more research is needed.

Most included studies examined child mental states, a principal concern for children with cancer during treatment, when better psychological wellbeing is linked to better treatment adherence [20], as well as during survivorship, when some literature suggests an elevated risk of adverse mental health outcomes [21]. Though mental state was a broad category encapsulating several distinct concepts (e.g., distress, depression), results mostly suggested fathers significantly contribute. Specifically, better father mental states [36, 37, 44, 45, 47, 58], more father involvement [45, 49, 56], better father coping [37], lower father parenting stress [48], higher father–child relationship quality [58], and more open father–child communication [60] were all linked to better child mental states. This aligns with research identifying a principal role of parent and family functioning in children with cancer's outcomes [3, 5, 18]. However, some studies, primarily published before 2000, also found null associations between child's mental state and father's mental state [43, 46, 48, 50, 57], parenting stress [53], and coping [44]. Though these findings add some ambiguity to understanding whether child mental states are linked to father contributions, null results tended to be from older publications, likely reflecting known increases in father involvement over the past few decades [12]. Thus, results indicate fathers may play an increasingly important role in their child's mental states. We suggest future research and interventions for children with cancer should be purposefully inclusive of fathers.

Father contributions, including coping, involvement, mental state, parenting stress, and father–child relationship quality, were significantly, positively associated with child coping, treatment adherence, behavioral adjustment, and relationship quality in adulthood. These associations represent significant roles for fathers across the cancer trajectory, from diagnosis through survivorship. In the earlier stages of childhood cancer, fathers may play a positive role in their child's coping and treatment adherence, which are known to contribute to child mental state and health outcomes both in the short- and long-term [22, 24–26]. Thus, including fathers in clinical settings and early interventions targeting coping skills and treatment adherence may yield stronger outcomes [10]. Additionally, results indicated fathers significantly contribute to their child's behavioral adjustment across the cancer trajectory, as well as better adult relationships in survivorship. This suggests that supporting fathers’ mental health, integration into clinical care, and inclusion in interventions across the child's treatment and into survivorship may mitigate known struggles with behavioral adjustment for childhood cancer survivors [23]. Additionally, supporting fathers may also bolster child health in survivorship as relationship quality is an important predictor of physical health [27]. Overall, findings highlight potential short-term and long-term benefits of father involvement for children with cancer. Further exploration of these associations could expand on existing research highlighting the important role fathers play in supporting children with other chronic conditions [16].

Child QOL and physical wellbeing had more ambiguous evidence regarding father contributions. Some studies suggested when fathers had worse mental states, their child had poorer QOL [48, 52]; however, counterintuitively, another study found fathers’ negative mental state was associated with higher child QOL [62]. Further, having a male caregiver as study participant was associated with worse child QOL [52], and there was no association between child QOL and fathers’ parenting stress [48]. One potential confounding factor contributing to these mixed findings could be fathers may increase their involvement in the context of more advanced disease [16]; if fathers are more likely to be involved with their child's care or participate in research when their child is doing poorly, this could explain lower QOL in the context of poorer father mental states or father involvement in research. Thus, future studies should better account for disease severity. For physical wellbeing, two studies of childhood cancer survivors suggested a more positive role for fathers [33, 38], and two studies of children on treatment suggested their involvement contributed to worse physical wellbeing [42, 48]. Though these findings suggest some ambiguity, it may be that fathers play a more significant role in the physical wellbeing of survivors than of children on treatment. This could suggest that supporting father involvement during survivorship might bolster child physical wellbeing, though more research is needed.

Though this review had several strengths, including a comprehensive search strategy with broad inclusion criteria and a systemic perspective linking father contributions to child outcomes, results should be interpreted considering several limitations. First, though we grouped findings into related topics (e.g., mental states represented 10 constructs), specific father contributions and child biopsychosocial outcomes are quite varied, limiting generalizability. Additionally, many studies were only fair or poor quality; thus, results should be extrapolated with caution. Also, all studies were from high-income countries, so results cannot be generalized to low- and middle-income nations. These limitations underscore the importance of generating high-quality, diverse research in this area. Finally, the age range was children diagnosed with cancer ≤18 years to limit findings to children likely under their father's care. Studies were excluded due to diagnosis at a later age; thus, future reviews might consider the inclusion of emerging and/or young adults.

The results of this scoping review have future research and clinical implications. First, findings underscore fathers’ potential influence on the biopsychosocial outcomes of their child with cancer; therefore, fathers should be systematically included in research participation and clinical care. Community-partnered research may aid in the recruitment and retention of fathers in pediatric research settings [65]. Additionally, prioritizing the inclusion of fathers in research or clinical work may be context-dependent; for example, adolescent males newly diagnosed with cancer tend to be more comfortable discussing fertility preservation options with male caregivers and providers [66]. Furthermore, roughly half of articles assessed during full-text stage review were excluded for not reporting or analytically differentiating caregiver type/gender. Accordingly, researchers should better solicit, document, and report caregiver demographic characteristics, and consider examining differences based on caregiver type/gender. Research from typically developing children indicates a distinct role of fathers for child development [12, 15]; thus, aggregating all caregivers in analyses is likely to miss important aspects of family processes. Future research should consider comparisons between families of children with cancer and typically developing children, as some research suggests associations between fathers’ contributions and child biopsychosocial outcomes may differ [45, 60]. Finally, most studies were correlational; future research should consider methods that may aid in understanding causality.

As the modern family landscape changes and fathers become increasingly involved in children's lives [12-14], it is crucial to understand and support their contributions, especially for children with cancer who benefit from a supportive family environment [3, 5, 18]. This scoping review examined 29 studies on fathers’ contributions to child biopsychosocial outcomes, highlighting the father's role in their child's mental state, coping, behavioral adjustment, relationship quality in adulthood, and treatment adherence. Further research is needed to validate and identify the most effective methods for supporting fathers and children in the context of pediatric cancer.

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank Drs. Cynthia Gerhardt and Christin Burd for their mentorship. This work was supported by the Training Program for Cancer Prevention and Control at Ohio State University (T32CA229114), though they had no role in the design and conduct of the study.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.