Parental smoking and respiratory outcomes in young childhood cancer survivors

This study has been previously published as a meeting abstract: “Effects of parental smoking on pulmonary outcomes in young childhood cancer survivors” at the Annual Meeting of the Swiss Society of Pediatrics, June 15th, 2023. Publication site: https://doi.org/10.57187/smw.2023.40104.

Abstract

Background

Passive exposure to cigarette smoke has negative effects on respiratory health. Childhood cancer survivors (CCS) are at increased risk for respiratory disease due to treatment regimens that may harm the respiratory system. The objective of this study was to assess the prevalence of parental smoking among CCS and investigate its association with respiratory outcomes.

Procedure

As part of the Swiss Childhood Cancer Survivor Study, between 2007 and 2022, we sent questionnaires to parents of children aged ≤16 years who had survived ≥5 years after a cancer diagnosis. Parents reported on their children's respiratory outcomes including recurrent upper respiratory tract infections (otitis media and sinusitis), asthma, and lower respiratory symptoms (chronic cough persisting >3 months, current and exercise wheeze), and on parental smoking. We used multivariable logistic regression to investigate associations between parental smoking and respiratory outcomes.

Results

Our study included 1037 CCS (response rate 66%). Median age at study was 12 years (interquartile range 10–14 years). Eighteen percent of mothers and 23% of fathers reported current smoking. CCS exposed to smoking mothers were more likely to have recurrent upper respiratory tract infections (OR 2.1; 95%CI 1.1–3.7) and lower respiratory symptoms (OR 2.0; 95%CI 1.1–3.7). We found no association with paternal smoking.

Conclusions

A substantial proportion of CCS in Switzerland have parents who smoke. Exposure to maternal smoking was associated with higher prevalence of upper and lower respiratory problems. Healthcare providers can support families by addressing caregiver smoking behaviors and providing referrals to smoking cessation programs.

Abbreviations

-

- CCS

-

- childhood cancer survivors

-

- ChCR

-

- Swiss Childhood Cancer Registry

-

- CI

-

- confidence Interval

-

- CNS

-

- central nervous system

-

- IQR

-

- interquartile range

-

- OR

-

- odds ratio

-

- SCCSS

-

- Swiss Childhood Cancer Survivor Study

-

- URTI

-

- upper respiratory tract infections

1 INTRODUCTION

Childhood cancer survivors (CCS) are at increased risk of pulmonary late effects because of their cancer treatment.1 Chemotherapy, radiotherapy, and surgery involving the chest and hematopoietic stem cell transplantation may affect lung function and lead to symptoms like chronic cough and exercise-induced shortness of breath.2, 3 Cumulative incidence of adverse pulmonary outcomes continues to increase years after completing cancer treatment.4 This indicates continuing susceptibility of survivors’ lungs to initiation and exacerbation of pulmonary diseases. Cancer therapies may also result in delayed immune reconstitution, leaving patients vulnerable to infections well beyond the conclusion of their treatment.5, 6 Consequently, infectious complications, such as upper respiratory tract infections (URTI) including sinusitis and otitis media, remain an important cause of late morbidity among survivors, impacting their health and increasing hospitalization rates.6, 7

Even among otherwise healthy individuals, environmental tobacco smoke is a risk factor for respiratory symptoms and infections. Children exposed to parental tobacco smoke have increased susceptibility to recurrent otitis media, asthma, cough, wheeze, and lower respiratory illnesses.8 Globally, nearly 40% of children are exposed to tobacco smoke.9 In Switzerland, almost one-third of children (31%) grow up in homes where a parent smokes.10 Parental smoking may have persistent effects on respiratory systems of children, with potential consequences such as impaired lung function and increased risk of respiratory symptoms continuing into adulthood.11 For CCS who may already have compromised respiratory health due to cancer treatments, these effects could be particularly concerning.4 Therefore, the aims of this study were to examine the prevalence of parental smoking among Swiss CCS aged ≤16 years and to investigate the associations between parental smoking and respiratory outcomes. We hypothesized that CCS exposed to maternal or paternal smoking would be more likely to experience respiratory outcomes, including symptoms and diseases, compared with those not exposed to parental smoking.

2 METHODS

2.1 The Swiss Childhood Cancer Survivor Study

The Swiss Childhood Cancer Survivor Study (SCCSS) is a nationwide, population-based, long-term follow-up study (www.swiss-ccss.ch) of survivors registered in the Swiss Childhood Cancer Registry (ChCR; www.kinderkrebsregister.ch).12 The ChCR is a national registry founded in 1976 that includes all Swiss residents diagnosed before the age of 20 years with leukemias, lymphomas, central nervous system (CNS) tumors, malignant solid tumors, or Langerhans cell histiocytosis.13 As part of the SCCSS, we sent questionnaires to former cancer patients who had survived for 5 years or more since their initial diagnosis. Detailed methods of the SCCSS have been published elsewhere.12 For this study, we analyzed questionnaires returned between 2007 and 2022 by parents of CCS younger than 16 years at the time of the study, who had answered questions on smoking status and their child's respiratory problems. The Ethics Committee of the Canton of Bern granted ethical approval to the ChCR and the SCCSS (166/2014; 2021-0146).

2.2 Definition of respiratory outcomes

The questionnaires assessed smoking within the family and children's respiratory symptoms and infections occurring during the previous 12 months. Questions inquired about the presence of asthma (yes/no), chronic cough lasting longer than 3 months (yes/no), recurrent sinusitis (yes/no), and recurrent otitis media (yes/no) in CCS. Questionnaires sent after 2015 also asked whether CCS had ever wheezed in their life (yes/no), in the last 12 months (yes/no), and during exercise (yes/no). From these questions, we created three main groups of respiratory outcomes for the analyses: recurrent URTI, asthma, and lower respiratory symptoms. Participants with recurrent URTI included those who reported either recurrent sinusitis, recurrent otitis media, or both. Participants with lower respiratory symptoms included those who had either chronic cough, at least one episode of wheeze in the past 12 months, or wheeze during exercise. The original questions in German can be found in Figure S2.

2.3 Explanatory variables

2.3.1 Parental smoking

We asked mothers and fathers separately if they had ever smoked. The specific question was: “Have you ever smoked cigarettes?” and possible answers were “No, never,” “Yes, but quit,” and “Yes, still smoke today.” If data were missing for both the maternal and paternal smoking status, participants were excluded from further analyses. We coded parental smoking as a binary variable (yes/no) where “yes” indicated a current smoker and “no” indicated a former or never smoker. We implemented this dichotomization to focus on the association of current smoking with recent respiratory outcomes and to ensure adequate statistical power, given the limited number of respiratory events among children whose parents were former smokers.

2.3.2 Sociodemographic characteristics

We assessed the following sociodemographic characteristics of CCS: age at study, sex, Swiss language region (German, French, or Italian), living situation, parental nationality, education, and employment status. We classified the living situation of CCS as living with both parents, only with the mother, only with the father, or in other circumstances (in a children's home or with relatives). Parents’ nationality was categorized as Swiss or other. We considered survivors as having a migration background if they had at least one parent whose nationality was other than Swiss. We divided the highest level of education attained by parents into three categories: primary schooling (compulsory schooling only, ≤9 years), secondary education (vocational training or upper secondary education), or tertiary education (university or technical college education).

2.3.3 Clinical characteristics

We received the following cancer-related variables from the ChCR: age at diagnosis, time since diagnosis, chemotherapy (yes/no), radiotherapy (yes/no), surgery (yes/no), hematopoietic stem cell transplantation (yes/no), relapse status (yes/no), and diagnosis coded according to the International Classification of Childhood Cancer, third edition (ICCC-3).14

2.4 Statistical analysis

We used medians and interquartile ranges (IQR) for continuous variables and numbers and percentages for categorical variables to describe the sociodemographic and clinical characteristics of survivors and parental smoking status. To examine associations between parental smoking and respiratory outcomes, we used logistic regression. First, we fitted univariable logistic regression models to identify sociodemographic and clinical factors associated with recurrent URTI, asthma, and lower respiratory symptoms. Exposure variables that showed an association with the outcome variables at a level of p < 0.1 were included in a multivariable logistic regression model. We incorporated maternal and paternal smoking, sex, and age a priori. Since all respiratory outcomes had a low number of missing answers (<10%), we assumed that the respective respiratory symptoms or diseases were absent. If there were missing values in other independent or dependent variables, a complete case analysis was performed. We used Stata (Version 16.1; Stata Corporation, Austin, TX) for all analyses.

3 RESULTS

3.1 Characteristics of the study population

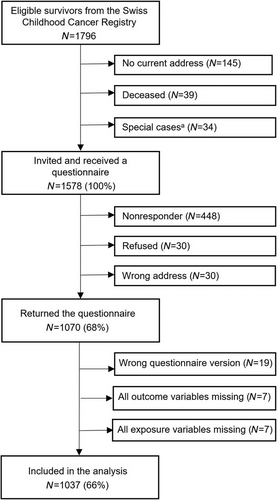

Of the 1796 eligible CCS identified through the ChCR, we sent questionnaires to the parents of 1578. Questionnaires were returned by parents in 1070 families (a response rate of 68%). We excluded questionnaires of 33 CCS for whom there were no answers to any of the questions on parental smoking or on respiratory outcomes. The final dataset used for the analysis included 1037 children (Figure 1). Their median age at the time of the study was 12 years (IQR 10−14), the median age at diagnosis was 3 years (IQR 2−5), and the median time since diagnosis was 8 years (IQR 7−10). The most common diagnoses were leukemia (39%), CNS tumors (16%), and neuroblastoma (9%) (Table 1). We compared cancer- and treatment-related characteristics of participants (n = 1037) and nonparticipants (n = 541) and found no significant differences between the groups (Table S1).

| N = 1037 | ||

|---|---|---|

| Socio-demographic characteristics | n | (%)a |

| Sex | ||

| Male | 578 | (56) |

| Female | 459 | (44) |

| Median age at study in years (IQR) | 12 (10−14) | |

| Swiss language region | ||

| German | 716 | (69) |

| French | 278 | (27) |

| Italian | 43 | (4) |

| Migration backgroundb | ||

| No | 679 | (65) |

| Yes | 358 | (35) |

| Living situation | ||

| With both parents | 889 | (86) |

| With mother only | 131 | (13) |

| With father only | 12 | (1) |

| Other (children's home, relatives) | 5 | (<1) |

| Cancer-related characteristics | n | (%)a |

|---|---|---|

| Median age at diagnosis in years (IQR) | 3 (2−5) | |

| Median time since diagnosis in years (IQR) | 8 (7−10) | |

| Diagnosis (ICCC-3) | ||

| Leukemia | 408 | (39) |

| Lymphoma | 64 | (6) |

| CNS tumor | 162 | (16) |

| Neuroblastoma | 95 | (9) |

| Retinoblastoma | 62 | (6) |

| Renal tumor | 83 | (8) |

| Hepatic tumor | 15 | (2) |

| Bone tumor | 20 | (2) |

| Soft tissue sarcoma | 67 | (7) |

| Germ cell tumor | 24 | (2) |

| Other tumorc | 2 | (< 1) |

| Langerhans cell histiocytosis | 35 | (3) |

| Treatment | ||

| Chemotherapyd | 856 | (83) |

| Radiotherapyd | 204 | (20) |

| Surgerye | 570 | (55) |

| Hematopoietic stem cell transplantationd | 86 | (8) |

| Relapse | 118 | (11) |

- Abbreviations: CNS, central nervous system; ICCC-3, International Classification of Childhood Cancer—Third Edition; IQR, interquartile range.

- a Column percentages are given.

- b Migration background was considered positive if at least one parent was not of Swiss nationality.

- c Other malignant epithelial neoplasms, malignant melanomas, and other or unspecified malignant neoplasms.

- d Any chemotherapy, radiotherapy, or hematopoietic stem cell transplantation alone or combined with other treatments.

- e Any surgery excluding port-a-cath insertion, alone or combined with other treatments.

Among parents, the median age at the time of the study was 43 years for mothers (IQR 40−47) and 46 years for fathers (IQR 42−50) (Table S2). Secondary education was the most frequently attained educational level of mothers (50%), while tertiary education was the level achieved by the highest proportion of fathers (49%). Almost all survivors lived with both parents (86%) (Table 1). Most fathers (80%), but only 10% of mothers worked full-time (Table S2).

3.2 Prevalence of parental smoking

Among mothers, 18% indicated that they currently smoked (95% confidence interval [CI] 15−20), 22% said they were former smokers who had quit before the study (95%CI 19−25), and 60% had never smoked (95%CI 57−63) (Table S2). Among fathers, 24% were active smokers at the time of the study (95%CI 21−27), 24% were former smokers (95%CI 22−27), and 52% had never smoked (95%CI 49−55). In 11% of families, both parents smoked (95%CI 9−13), and in 20% only one parent was an active smoker (95%CI 18−23). In most families, none of the parents smoked (69%, 95%CI 66−72) (Figure S1). Smoking was more common in parents with a lower educational level and among unemployed fathers (Table S3).

3.3 Prevalence of respiratory outcomes

Eight percent of survivors reported recurrent URTI (95%CI 7−10), while asthma was reported by 5% (95%CI 4−7) (Table 2). In total, 6% of survivors reported lower respiratory symptoms (95%CI 5−8), including 2% with chronic cough (95%CI 1−3), 6% with wheeze (95%CI 4−8), and 6% with wheeze during exercise (95%CI 4−8). Almost one-third of survivors with lower respiratory symptoms (32%) reported more than one of these symptoms.

| N = 1037 | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| n | % | (95%CI) | |

| Recurrent URTIa | 85 | 8 | (7−10) |

| Recurrent otitisb | 54 | 5 | (4−7) |

| Recurrent sinusitis | 35 | 3 | (2−5) |

| Asthma | 54 | 5 | (4−7) |

| Lower respiratory symptomsc | 65 | 6 | (5−8) |

| Chronic cough | 22 | 2 | (1−3) |

| Current wheezed | 33 | 6 | (4−8) |

| Wheeze during exercised | 32 | 6 | (4−8) |

- Abbreviations: CI, confidence interval; URTI, upper respiratory tract infections.

- a Defined as having reported at least one of the following recurrent infections.

- b Question not asked in a part of questionnaires (total N = 1003).

- c Defined as having reported at least one of the following symptoms.

- d Question not asked in a part of questionnaires. The percentages are derived from the participants that were asked this question (total N = 569).

3.4 Associations between parental smoking and respiratory outcomes

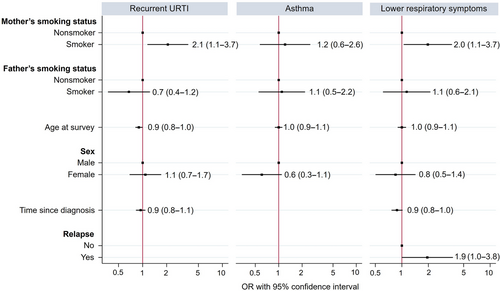

In multivariable regression, survivors whose mothers smoked were more likely to have recurrent URTI (odds ratio [OR] 2.1, 95%CI 1.1–3.7) and lower respiratory symptoms (OR 2.0, 95%CI 1.1–3.7) compared with survivors whose mothers did not smoke (Figure 2 and Table S4). Paternal smoking did not show an association with recurrent URTI, asthma, or lower respiratory symptoms.

Older survivors were less likely to have recurrent URTI (OR 0.9, 95%CI 0.8–1.0). With increasing time since diagnosis, survivors were less likely to have recurrent URTI in the univariable regression (OR 0.9, 95%CI 0.8–1.0), but this association was not seen after adjusting in the multivariable regression (OR 0.9, 95%CI 0.8–1.1). Survivors with a history of relapse were more likely to have lower respiratory symptoms in the univariable model (OR 2.1, 95%CI 1.1–3.9), with the trend persisting in the multivariable model (OR 1.9, 95%CI 1.0–3.8). Sex was not associated with any of the respiratory outcomes. Detailed results from univariable logistic regression can be found in Table S5.

4 DISCUSSION

A substantial proportion of young CCS in this nationwide, population-based cohort study are exposed to parents who smoke (31%). We found that maternal smoking was associated with a twofold increased risk of recurrent URTI and lower respiratory symptoms.

Despite the general decline in smoking worldwide over the past two decades,15, 16 our study found that a significant proportion of Swiss CCS are exposed to parental smoking, with 18% of mothers and 24% of fathers reported as smokers. A school-based survey on children's respiratory health conducted in the Canton of Zurich between 2013 and 2016 found slightly higher rates, with 20% of mothers and 30% of fathers smoking.17 Similarly, a 2017 nationwide report on tobacco use by the Swiss Federal Statistical Office indicated that 23% of women and 31% of men aged 15 years and older were daily or occasional smokers.16 Yet little is known about parental smoking in the families of CCS. A study conducted in the USA found that only 6% of parents of CCS were active smokers compared to 12% of adults in the general population.18, 19 The lower prevalence among parents of CCS may be because parents of survivors tend to adopt more health-conscious behaviors.18 However, it could also be that underreporting is more common in this population.

Our hypothesis that CCS exposed to parental smoking would be more likely to experience respiratory outcomes was partially confirmed, as only maternal smoking was associated with a greater risk of recurrent URTI and lower respiratory symptoms among young (<16 years) CCS. These results are in line with questionnaire-based studies in the general population, which consistently found a stronger impact of maternal smoking on respiratory health than paternal smoking.20-23 Women are more often primary caregivers and spend more time on average at home with their children.24 In our study, almost all CCS lived with both parents (86%) or only their mothers (13%), and there was a pronounced difference in the employment status of parents, with only 10% of mothers having full-time jobs compared with 80% of fathers. This suggests that survivors may be more susceptible to adverse effects of maternal smoking due to increased exposure to tobacco smoke within the household environment.

Passive smoking contributes to respiratory morbidity in children.8 In the late 1990s, a series of comprehensive systematic reviews with meta-analyses revealed consistent evidence for associations between maternal smoking and recurrent otitis media (OR 1.48, 95%CI 1.08–2.04),25 wheeze (OR 1.28, 95%CI 1.19–1.38), and cough (OR 1.40, 95%CI 1.20–1.64).26 A multicountry, questionnaire-based study of 220,407 children (6–7 years) and 350,654 adolescents (13–14 years) found that maternal smoking was associated with wheeze both in children (OR 1.28, 95%CI 1.22–1.34) and adolescents (OR 1.32, 95%CI 1.26–1.37).21 Compared to those results, our observations in CCS indicated slightly stronger associations between maternal smoking and recurrent URTI and lower respiratory symptoms. Survivors with a history of relapse were more likely to experience lower respiratory symptoms, perhaps because of more intense and prolonged treatments including chemotherapy, radiation, and hematopoietic stem cell transplantation27, 28 Even after accounting for the increased risk from relapse, exposure to maternal smoking was associated with lower respiratory symptoms, highlighting the independent harmful effect of parental smoking for CCS.

In contrast to previous studies conducted among the general population,21-23, 29, 30 we found no association between parental smoking and asthma. A systematic review found that children whose parents smoked were more likely to have asthma than children with nonsmoking parents (OR 1.21, 95%CI 1.10–1.34).31 The lack of association observed in our study may be due to underreporting or underdiagnosing of asthma. Several studies found that children with parents who smoke were less likely to receive an asthma diagnosis.32, 33 This could be because parents who smoke are less likely to seek medical advice regarding mild respiratory symptoms that could be related to smoking in the family.32, 33 Another potential explanation is that CCS often receive ongoing medical care focusing on late effects of cancer treatment, which may lead to respiratory symptoms being attributed to these effects rather than asthma. Additionally, immunosuppressive therapies used during cancer treatment can suppress inflammatory responses,34, 35 potentially masking asthma symptoms and contributing to underdiagnosis among survivors.

The cross-sectional design of this study does not allow causal conclusions regarding smoking and respiratory outcomes. However, the biological plausibility connecting passive smoking and respiratory conditions is well established.8 Passive tobacco smoke has toxic effects on the mucosa, impairs ciliary function and local immune defenses, and results in prolonged inflammation and susceptibility to infections such as otitis media and sinusitis.36 It also contributes to airway thickening and irritation, thereby predisposing children to respiratory symptoms including wheeze and cough.37 Future studies should apply a longitudinal design, which would not only strengthen causal conclusions regarding passive smoking and respiratory health in CCS, but also allow examination of changes in parental smoking behavior over time and associated changes in related health outcomes of CCS.

Self-reported exposures and outcomes may have been subject to recall bias and led to misclassification of some respiratory outcomes in our study. Additionally, we did not collect data on whether parents smoked in proximity to their child, limiting our ability to assess dose–response relationships and exposure to secondhand and thirdhand smoke. To accurately assess survivors’ exposure to passive smoke, future studies should include objective biological markers such as urinary cotinine levels. Due to limited statistical power from the low number of respiratory events, we could not determine associations between parental smoking and respiratory outcomes within different diagnostic and cancer treatment subgroups. Finally, our study did not have a control group. Including a control group in future studies would allow investigation of whether the effects of parental smoking and parental smoking cessation on respiratory health are larger in CCS than in peers without a cancer history.

The strengths of our study include the population-based design and a high response rate, which ensured that the study population is representative of CCSs in Switzerland. We used high-quality clinical information based on medical records from the ChCR and assessed a diverse spectrum of respiratory outcomes.

In conclusion, our study found that exposure to parental smoking is associated with an increased risk of respiratory symptoms and infections among Swiss CCS. Integrating parental smoking cessation strategies into the medical and psychosocial care of childhood cancer patients is essential to create a healthier home environment and promote respiratory health in this vulnerable population. Healthcare providers can support families by addressing caregiver smoking behaviors and providing referrals to specific smoking cessation programs, such as those offered by the Swiss Lung Association (www.lungenliga.ch), the Swiss Cancer League (www.krebsliga.ch), and the national “SmokeFree” campaign (www.stopsmoking.ch), which include effective strategies like counseling sessions and e-health interventions.38, 39 The World Health Organization offers valuable guidelines that can further support smoking cessation efforts globally.40

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank all survivors for participating in our study, the study team of the Childhood Cancer Research Group, the data managers of the Swiss Paediatric Oncology Group, and the team of the Swiss Childhood Cancer Registry. We also thank Christopher Ritter for editorial assistance. This work was supported by the Swiss Cancer Research and Swiss Cancer League (grant numbers HSR-4951-11-2019, KFS-5027-02-2020, KFS-5302-02-2021, KLS/KFS-4825-01-2019, KLS/KFS- 5711-01-2022), Childhood Cancer Switzerland, Kinderkrebshilfe Schweiz, Stiftung für krebskranke Kinder—Regio Basiliensis, and the University of Basel Research Fund for Excellent Junior Researchers.

Open access funding provided by Universitat Bern.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST STATEMENT

The authors declare no conflict of interest related to the study.