Type of cancer and complementary and alternative medicine are determinant factors for the patient delay experienced by children with cancer: A study in West Java, Indonesia

Abstract

Introduction

Most pediatric cancer patients in developing countries present at an advanced stage due to delayed diagnosis, being an important barrier to effective care. The objective of this study was to evaluate the associated factor of patient delay and explore significant parental practice-associated risk factor to patient delay.

Methods

This was a sequential mixed methodology, utilizing data from the Indonesian Pediatric Cancer Registry for clinical variables and completed interviews with parents using structured questionnaires to obtain their sociodemographic data. A binary logistic regression analysis model was fitted to identify factors associated with patient delay. Additional semi-structured interviews related to parental practice of using complementary and alternative medicine (CAM) were administered to 30 parents. Thematic framework analysis was performed on qualitative data to explore determinant factors of parental practice of using CAM.

Results

We interviewed 356 parents with children with cancer. The median patient delay was 14 days (interquartile range [IQR]: 6–46.5 days). The most extended delay was in patients with malignant bone tumors (median 66, IQR: 14–126). In multivariable logistic regression analysis, solid cancer (odds ratio [OR] = 5.22, 95% confidence interval [CI]: 2.79–9.77, p < .001) and use of CAM (OR = 1.86, 95% CI: 1.13–3.08, p = .015) were associated with patient delay. Qualitative interviews highlighted key issues relative to determinant parental factors using CAM, including vague initial childhood cancer symptoms, parental health-seeking behavior, CAM availability and accessibility, also barriers of healthcare facilities.

Conclusion

Type of cancer and use of CAM are essential factors that cause patient delay. It should be addressed in the future childhood cancer awareness and childhood cancer diagnosis pathway.

Abbreviations

-

- CAM

-

- complementary and alternative medicine

-

- IP-CAR

-

- Indonesian Pediatric Cancer Registry

-

- LMIC

-

- low middle-income country

1 INTRODUCTION

Every year, it is estimated that at least 400,000 new childhood cancer cases occur, or the equivalent of more than 1000 new cases per day.1 Far most (90%) live in countries with low middle-income per capita, with a survival rate of only 20%–40% at best, compared to countries with a higher income per capita, where the cure rate is around 80%–90%.1-8 One of the causes of the high mortality rate is the delay in patients coming to health facilities, with patients being diagnosed in an advanced stage.9 Factors that contribute to this delay are the difficulty in recognizing early signs of childhood cancer, barriers to access healthcare, and socioeconomic conditions.10-12

Patient pathways to presentation to healthcare professionals and initial management in primary care are critical determinants of outcomes in cancer.13 Reducing diagnostic delays may improve prognosis by increasing the proportion of early-stage cancers being identified.14 Patient delay is the period from the day the symptoms appear until the patient comes to the health facility for the first time.15 In previous studies, the patient's delay ranged from 3 to 86 days in developing countries, while in developed countries it was 1–9 days.15-23 The following factors that influence patient delay include cancer biology, socioeconomic characteristics, as well as geographic and cultural factors, and also healthcare system.10, 11, 16, 24 One of the sociocultural factors to be emphasized is the treatment preference of using complementary and alternative medicine (CAM) as the first choice for parental health seeking behavior largely in low middle-income countries (LMICs).25 Several oncology studies, including adult and pediatric settings, have addressed CAM as a contributing factor for diagnostic and treatment delay.26-28

There were limited studies about pediatric cancer delay and its associated factors, especially cultural factors available in Southeast Asia.16 It is important to determine whether similar clinical and social factors influence patient delay in children with cancer cared in Indonesia. To find out, we undertook a mixed methods study.

2 METHODS

2.1 Study design

This was a sequential mixed methodology that used quantitative methods, followed by qualitative methods.29, 30 Initially, we conducted a quantitative analysis to determine factors-related patient delay. To do so, we combined registry data, closed-ended questionnaire (Supporting Information S1) to complete family socioeconomic and demographic data adapted from Statistics Indonesia Socioeconomic Survey by telephone. After we identified the significant contributing factors of patient delays, we conducted in-depth interview with parents-related factors contributed to patient delays using interview-guided questions especially related to cultural factors such as parental practice of CAM (Supporting Information S2).31 Thematic analysis methods help to interpret and contextualize the qualitative finding, especially on significant factors that related to parental seeking health behavior.32

2.2 Study population

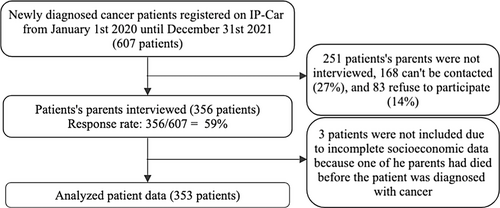

This study was conducted at Dr. Hasan Sadikin Hospital. Patient socioeconomic-demographic data and clinical variables were imported from the “Indonesian Pediatric Cancer Registry (IP-CAR)” from January 1, 2020 until December 31, 2021. We included all the patients through IP-CAR data input, and excluded them for various reasons shown in Figure 1.

2.3 Explanatory factor

We sought to determine which of the three following factors, which were patient socioeconomic and demographic characteristic, family sociodemographic, and cancer characteristic associated with patient delay. Type of cancer according to the International Classification of Childhood Cancer, 3rd edition (ICCC) based on histopathology examination, and suspect cases, were determined based on a clinically high suspicion of pediatric cancer without histopathologic confirmation.33 For further analysis, on each explanatory factor were grouping according agreement definition that can be found in Supporting Information S3.34 Patient delay was defined as the number of days elapsed between the symptoms appearing for the first time and the patient coming to the health facility for the first time. These intervals were measured in days, and designated as “early” when they were less than or equal to the median value, or as “late” when they were more than the median value.35

2.4 Data analysis

Quantitative data were analyzed with the Statistical Package for the Social Sciences for Windows (version 26.0; SPSS Inc, Chicago, IL, USA). Descriptive statistics included percentages and measurements of the central tendency (median and interquartile range [IQR]) for age, birth order, number of children, and distance to the first health facility. Bivariable analyses were performed using chi-square analyses, and multivariable analyses were carried out using a logistic regression model.36 Variables with p < .25 in the bivariate analysis and relevant were included in the multivariate analysis. Statistical significance was established at 5% for a two-sided test. The qualitative data were analyzed using thematic analysis to help interpret and contextualize the quantitative finding, especially on significant factors that related to parental seeking health behavior.32 The first author (Nur Melani Sari) conducted all the interviews. The final sample size was determined by thematic saturation (n = 30), the point at which new data appears to no longer contribute to the findings due to the repetition of themes and comments by participants.37 The interview guide used a list of questions that had been tested before and can be found in Supporting Information S4.38 First, three members of the study team independently coded questionnaires and then collaborated to construct the intial coding scheme, which was agreed upon by all team members. The Research Ethics Committee from RSUP Dr. Hasan Sadikin Bandung approved the study of Universitas Padjadjaran with the number 997/UN6.KEP/EC/2021.

3 RESULTS

During the study period, among 607 newly diagnosed patients with cancer presented at RSUP Dr. Hasan Sadikin Bandung, the parents of 356/607 (59%) children were interviewed, 168/607 (27%) parents could not be contacted through a registered phone number in the medical record (five attempts) and not responded through a letter, 83/607 (14%) families refused to participate (Figure 1). Three patients were not included in the analysis due to incomplete socioeconomic data because one of the parents had died before the patient was diagnosed. For the remaining 353, we collected patient and family characteristics, as shown in Table 1. The median duration of delay in patients was 14 (IQR: 6–46.5; range: 2–760) days.

| Variable | Total (n = 353) | |

|---|---|---|

| Patient characteristics | ||

| Sex, n (%) | ||

| Male | 194 | (55) |

| Female | 159 | (45) |

| Age at diagnosis (years), n (%) | ||

| 0–4 | 172 | (48.7) |

| 5–9 | 76 | (21.5) |

| ≥10 | 105 | (29.7) |

| Median age, IQR (years) | 5 | (2–10) |

| Birth order, n (%) | ||

| ≤2 | 298 | (84.4) |

| >2 | 55 | (15.6) |

| Median, IQR | 1 | (1–2) |

| Insurance ownership, n (%) | ||

| Government or private | 347 | (98.3) |

| Not owned | 6 | (1.7) |

| Use of CAM, n (%) | ||

| Yes | 121 | (34.3) |

| No | 232 | (65.7) |

| Cancer type, n (%) | ||

| Suspect | 34 | (9.6) |

| Solid tumor | 177 | (50.1) |

| Non-solid tumor | 142 | (40.2) |

| Cancer stage, n (%) | ||

| Early stage | 143 | (40.5) |

| Undetermined/advanced stage | 210 | (59.5) |

| Family characteristics | ||

| Parents’ marital status, n (%) | ||

| Married | 339 | (96) |

| Separated | 14 | (4) |

| Number of children, n (%) | ||

| ≤2 | 265 | (75.1) |

| >2 | 88 | (24.9) |

| Median, IQR | 2 | (1–2.5) |

| Father's age at child's diagnosis (years), n (%) | ||

| ≤35 | 146 | (41.4) |

| >35 | 207 | (58.6) |

| Median age, IQR (years) | 37 | (33–41) |

| Education, n (%) | ||

| High education | 193 | (54.7) |

| Low education/no formal education | 160 | (45.3) |

| Occupation | ||

| Formal | 124 | (35.1) |

| Informal | 222 | (62.9) |

| Not working | 7 | (2) |

| Religion, n (%) | ||

| Muslim | 347 | (98.3) |

| Non-Muslim | 6 | (1.7) |

| Income, n (%) | ||

| Above the West Java UMP | 183 | (51.8) |

| Below the West Java UMP | 170 | (48.2) |

| Mother's age at child's diagnosis (years), n (%) | ||

| ≤35 | 190 | (53.8) |

| >35 | 163 | (46.2) |

| Median age, IQR (years) | 35 | (30–38) |

| Education, n (%) | ||

| High education | 181 | (51.3) |

| Low education/no formal education | 172 | (48.7) |

| Occupation, n (%) | ||

| Formal | 17 | (4.8) |

| Informal | 17 | (4.8) |

| Housewife/not in paid work | 319 | (90.4) |

| Religion, n (%) | ||

| Moslem | 347 | (98.3) |

| Non-Moslem | 6 | (1.7) |

| Income, n (%) | ||

| Above the West Java UMP | 103 | (29.2) |

| Below the West Java UMP | 250 | (70.8) |

| Residential area, n (%) | ||

| Rural | 294 | (83.3) |

| Urban | 59 | (16.7) |

| Distance to the first health facility (km), n (%) | ||

| ≤2 | 229 | (64.9) |

| >2 | 124 | (35.1) |

| Median distance, IQR (km) | 2 | (1–4.5) |

- Abbreviations: IQR, interquartile range; UMP, provincial minimum wage.

Different components affecting the patient's delay duration for each type of cancer are in Table 2. The shortest delay was in patients with myelodysplastic syndromes (median 2, IQR: 2–1), while the most prolonged delay was in patients with malignant bone tumors (median 66, IQR: 14–126).

| Cancer type | Median patient delay [IQR], days | n (%) |

|---|---|---|

| Suspect | 12.5 [5–28.5] | 34 (9.6) |

| Solid tumor | 31 [7–69.5] | 177 (50.1) |

| Lymphomas and reticuloendothelial neoplasms | 25.5 [3.75–72.75] | 30 (16.9) |

| CNS and miscellaneous intracranial and intraspinal neoplasms | 7.5 [0–15.25] | 10 (5.6) |

| Neuroblastoma and other peripheral nervous cell tumors | 52.5 [25.75–60.75] | 8 (4.5) |

| Retinoblastoma | 49.5 [22.75–132] | 40 (22.5) |

| Renal tumors | 42.5 [7–117.5] | 20 (11.2) |

| Hepatic tumors | 38.5 [16.25–30.5] | 8 (4.5) |

| Malignant bone tumors | 66 [14–126] | 20 (11.2) |

| Soft tissue and other extraosseous sarcomas | 31 [6.5–61] | 17 (9.6) |

| Germ cell tumors, trophoblastic tumors, and neoplasms of gonads | 14 [10–24.5] | 13 (7.3) |

| Other malignant epithelial neoplasms and malignant melanomas | 21 [12–41] | 11 (6.2) |

| Non-solid tumor | ||

| Lymphoid leukemias | 8 [6–17] | 142 (40.2) |

| Acute myeloid leukemia | 11 [7–21] | 94 (66.2) |

| Chronic myeloproliferative diseases | 10 [7–17.5] | 25 (17.6) |

| Myelodysplastic syndrome and others | 4 [0.75–10] | 12 (8.5) |

| Myeloproliferative diseases | 2 [2–17] | 11 (7.7) |

Bivariate chi-square analysis showed a significantly higher risk for longer patient delay in children diagnosed with solid tumors (odds ratio [OR] = 4.17, 95% confidence interval [CI]: 2.68–6.51, p < .001), those whose diagnoses were of undetermined/advanced-stage cancer (OR = 2.29, 95% CI: 1.48–3.53, p < .001), and those who use CAM (OR = 1.63, 95% CI: 1.05–2.54, p = .031). To confirm solid tumor as a risk factor, we performed a sensitivity analysis excluding the suspected malignancy group (n = 34) as one of the cancer types in multivariate analysis (adjusted-OR = 5.02, 95% CI: 3.10–8.24, p = .000, data not shown). Sex, age at diagnosis, birth order, parent's marital status, number of children, parent's age at diagnosis, parent's education, parent's occupation, parent's religion, parent's income, residential area, and distance to the first health facility were not significantly associated with a higher risk of patient's delay in the bivariable analysis. In the multivariable logistic regression analysis, solid tumor (OR = 5.22, 95% CI: 2.79–9.77, p < .001), insurance ownership (OR = 0.08, 95% CI: 0.01–0.76, p = .035), and use of CAM (adjusted OR = 1.86, 95% CI: 1.13–3.08, p = .015) were independently associated with patient delay (Table 3).

| Bivariate analysis | Multivariate analysis | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Variable | OR | 95% CI | p | OR | 95% CI | p |

| Patient characteristic | ||||||

| Sex, n (%) | ||||||

| Male | 1 | Reference | ||||

| Female | 1.03 | 0.68–1.57 | .877 | |||

| Age when diagnosis (years), n (%) | ||||||

| 0–4 | 1 | Reference | 1 | Reference | ||

| 5–9 | 1.08 | 0.65–1.79 | .774 | 1.34 | 0.73–2.44 | .343 |

| ≥10 | 0.88 | 0.56–1.39 | .584 | 1.00 | 0.55–1.84 | .987 |

| Birth order, n (%) | ||||||

| ≤2 | 1 | Reference | ||||

| >2 | 1.15 | 0.64–2.04 | .643 | |||

| Insurance ownership, n (%) | ||||||

| Own insurance | 1 | Referenc | 1 | Reference | ||

| (Government or private) not owned | 0.197 | 0.02–1.70 | .139 | 0.08 | 0.01–0.76 | .028 |

| Use of CAM medicine, n (%) | ||||||

| Yes | 1.63 | 1.05–2.54 | .031 | 1.86 | 1.13–3.08 | .015 |

| No | 1 | Reference | 1 | Reference | ||

| Cancer type, n (%) | ||||||

| Suspect | 0.73 | 0.36–1.48 | .384 | 1.82 | 0.75–4.42 | .185 |

| Solid tumor | 4.17 | 2.68–6.51 | <.001 | 5.22 | 2.79–9.77 | <.001 |

| Non-solid tumor | 1 | Reference | 1 | Reference | ||

| Cancer stage, n (%) | ||||||

| Early stage | 1 | Reference | 1 | Reference | .953 | |

| Undetermined/advanced stage | 2.29 | 1.48–3.53 | <.001 | 1.02 | 0.55–1.87 | |

| Family characteristic | ||||||

| Marital status, n (%) | ||||||

| Married | 1 | Reference | 1 | Reference | ||

| Separated | 2.60 | 0.80–8.47 | .111 | 2.77 | 0.76–10.16 | .124 |

| Number of children, n (%) | ||||||

| ≤2 | 1 | Reference | ||||

| >2 | 0.95 | 0.58–1.54 | .829 | |||

| Father | ||||||

| Age when diagnosed (years), n (%) | 1 | |||||

| ≤35 | Reference | |||||

| >35 | 0.78 | 0.51–1.20 | .261 | |||

| Education, n (%) | ||||||

| High education | 1 | Reference | ||||

| Low education/no formal education | 0.80 | 0.53–1.22 | .308 | |||

| Occupation | ||||||

| Formal | 1 | Reference | .056 | 1 | Reference | |

| Informal | 0.66 | 0.42–1.01 | .698 | 0.62 | 0.38–1.02 | .058 |

| Not working | 1.35 | 0.30–6.12 | 0.86 | 0.14–5.06 | .864 | |

| Religion, n (%) | ||||||

| Moslem | 1 | Reference | ||||

| Non-Moslem | 0.50 | 0.09–2.75 | .423 | |||

| Income, n (%) | ||||||

| Above the West Java UMP | 1 | Reference | ||||

| Below the West Java UMP | 0.92 | 0.61–1.40 | .708 | |||

| Mother | ||||||

| Age at diagnosis (years), n (%) | ||||||

| ≤35 | 1 | Reference | 1 | Reference | ||

| >35 | 0.72 | 0.47–1.09 | .121 | 0.77 | 0.46–1.29 | .323 |

| Education, n (%) | ||||||

| High education | 1 | Reference | ||||

| Low education/no formal education | 0.84 | 0.56–1.28 | .424 | |||

| Occupation, n (%) | ||||||

| Formal | 1 | Reference | ||||

| Informal | 1.14 | 0.43–3.02 | .795 | |||

| Housewife/not working | 0.67 | 0.33–1.37 | .274 | |||

| Religion, n (%) | ||||||

| Moslem | 1 | Reference | ||||

| Non-Moslem | 0.50 | 0.09–2.75 | .423 | |||

| Income, n (%) | ||||||

| Above the West Java UMP | 1 | Reference | ||||

| Below the West Java UMP | 0.91 | 0.58–1.45 | .700 | |||

| Residential area, n (%) | ||||||

| Rural | 1.12 | 0.64–1.96 | .686 | |||

| Urban | 1 | Reference | ||||

| Distance to the first health facility (km), n (%) | ||||||

| ≤2 | 1 | Reference | ||||

| >2 | 0.91 | 0.59–1.41 | .684 | |||

- Abbreviations: CI, confidence interval; OR, odds ratio.

3.1 Qualitative results

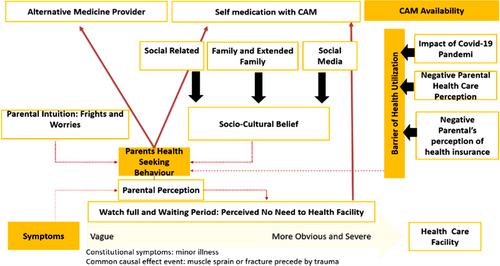

The analysis generated interrelated themes with verbatim methods that describe factors associated with parents' use of CAM prior to contact with a healthcare provider, and captured four domains that were vague initial childhood cancer symptoms, parental seeking behavior depending on sociocultural belief, parental fright and worries/self-care, parental disease perception, CAM availability, and barrier of healthcare facilities as determinant factors of the parental practice of using CAM are presented in Figure 2.

Supporting statements are presented in Table 4, while the explanation from each factor are cited in Supporting Information S4.

| Determinant factors | Statement |

|---|---|

| Vague and severity of initial pediatric cancer symptoms | “I thought it was an ordinary muscle sprain, she was feeling pain in her groin, and I thought it was a common symptom, that is why I brought her to get a massage several times.” |

| “Before I knew my daughter suspected of having leukemia, the only bothering symptoms was that she felt a decrease in appetite, so I tried to self-medicate by buying herbal medicine, which is well known and usually taken to boost immunity that has been recommended by a midwife once in the previous consultation.” | |

| Parental intuition (fright and worries) and self-medication | “I just knew there was something wrong happening with my child, she did not like usual, so I just gave her honey that I bought in the drug store.” |

| “Previously, when my child got just 2 days of fever, I went to the doctor, and the doctor gave me four types of drugs without proper explanation, I did not give the drug to her, and voila the fever disappeared.” | |

| “It has become a habit in our family to treat symptoms that are not too severe with over-the-counter medicine, just to see if there is an improvement. If there is no improvement, I will take my child to the doctor.” | |

| Parental sociocultural belief | “My grandmother having a breast cancer, so as daughter-in-law, I just followed what she said, to have natural leaves decoction if my child getting sick” |

| “My neighbors recommended a famous bone setter in the next village that has succeeded in giving treatment in many fracture cases without operation.” | |

| “When I noticed a lump in my child's neck, my close relative told me it could be an abscess, and there was a religious Moslem cleric that usually gave a holy water to resolve the symptoms, but I stopped when realized the lump was getting bigger, and even the eyes was always out from the globe” | |

| Barrier of healthcare utilization | “Primary health facility was near, but the queue was long, and my son is still a small child. I was afraid my son will have to take blood for several attempts like the previous consultation, and mostly I had been treated by midwives, the doctor is not always there.” |

| “I was planning to take my daughter to healthcare but her mother was pregnant and waiting to have birth, meanwhile my daughter was very dependent on her mother. At the same time, I got COVID-19 infected, there was no relative available to take my son to the doctor at that time.” | |

| Complementary and alternative medicine (CAM) availability | “Famous bone setter was near my village, even a lot of patients from outside the city come over to seek help, my neighbor told me that” |

| “There was a tv show to expose the success story of patient who previously succeeded without medical treatment, so at that time I wanted to try that when my child got fracture” | |

| “The Instagram feed showed the advertising of CAM, including the testimony story, and during those pandemic times, it was easy to order that online |

4 DISCUSSION

Cancer that is identified early is more likely to respond to effective treatment, and patients have a greater probability of survival, less suffering, and often require less expensive and intensive treatment.39 The current study found that the median patient delay was 14 days with a broader range of (IQR: 6–46.5; range: 2–760) days. Some of the studies from other developing countries showed the same values, shorter range (3–9 days) and even longer with a duration of 30–112 days.2, 10, 15-19 Comparing previous findings with the other early-diagnosis studies was difficult due to inconsistent and lack of consensus on the definitions and terms used, and different time intervals measured along the diagnostic path.39 Therefore, several terminologies have been nominated as preferable alternatives in the future study, such as diagnostic interval, patient lag time, appraisal interval, help-seeking interval, or “time to presentation” use.40, 41 Most of the study-related patient delays in pediatric cancer population use are largely treated as a dichotomous variable, with a defined time point beyond which the interval has previously been classified as “delayed.”15-18, 20 Most studies use dichotomous variable based on median, meanwhile another approach was to generate quartiles from their patient interval data and use the 25th and 75th quartiles to represent short and long “delay,” respectively.

In this study, both bivariate and multivariate analysis confirms only the cancer type, and the use of CAM has a significant effect on patient delays. Moreover, even though insurance ownership significantly affected patient delays (OR = 0.08, 95% CI: 0.01–0.76, p = .035), it was shown as an adverse risk. The phenomenon is contrary to the standard hypothesis that ownership will guide parents to see the healthcare facility faster. The first possible explanation is that many parents enrolled in national health insurance after seeing a medical doctor, pursuing the patient's need for diagnosis referral. The questionnaire should have been more detailed regarding the time of insurance ownership when the parent notices the sign of pediatric cancer to generalize the result to the population. The subsequent reason is that non-ownership was present in only a small group consisting of six patients, which can be easily confounded with other variables. A study from Indonesia showed that having insurance did not affect the diagnosis delay.16

The study results contrast with previous Indonesian and South African studies, which showed that cancer type has no significant effect on patient delay.16, 18 Nevertheless, other studies have shown that cancer type significantly affects patient delay.23 Malignant bone tumors had the most prolonged median patient delay, which is in keeping with findings among children in Canada and South Africa, where bone tumors also had the most extended median total delay.17, 18 This study also uncovered that solid cancers have a longer median patient delay (66, IQR: 14–126) than non-solid cancers, in line with Turkey's studies.20 The early symptoms sign of a bone tumor usually precedes pathological fracture and is manifested as a muscle sprain or strain, which is usually treated with a traditional and alternative message. The onset is mostly in the adolescent group, which was a significant risk factor for diagnosis in previous studies.10 This result was validated in the qualitative section of this study, most parents took their children to a traditional bone setter that has been well known and followed their elders' or relatives' suggestions.

The parental health-seeking behavior relating to the use of CAM before seeing the medical officer was another factor increasing the risk of patient delays. In this study, the use of CAM was found to be a strong predictor of patient delay, as in previous studies in Indonesia and other LMICs or even high-income countries.16, 32-48 CAM is very popular, and a systematic review of CAM prevalence surveys worldwide found a prevalence of 23%–62%, and for over-the-counter CAM 25%–46%, and also commonly used for children, with prevalence estimates from 12% to 51% in the United States, Canada, Australia, and the United Kingdom.49 As per the Indonesia Family Life Survey in 2014–2015, from 15,739 children (0–14 years), the proportion who found prevalence of traditional or herbal medicines use was 6.2%, the use of traditional health practitioners was 3.4%, and the use of traditional medicines and/or traditional practitioners was 8.8%.50 Studies related to the use of CAM in the Indonesian adult cancer population were more common than limited studies in pediatric. A study in the Indonesian adult cancer population observed that 43% of 153 patient delays from one national hospital in Indonesia had a history of alternative treatment.51 Time of using CAM was varied, started before the diagnosis and is less frequent than after the diagnosis was established.52

The type of CAM used was different across countries, from qualitative data, the parents have experience with CAM consisting of biology-based therapies (honey, holy water, vitamin, herbal, leaves decoction), physical therapies without tools (message, traditional bone setter), and physical therapy with tools (leech suck).53 Meanwhile, studies from South India report that 7.58% used CAMs, of which the most commonly used was Ayurveda followed by Siddha, and a study in Swiss pediatric cancer population found the most type of CAM used was homeopathy.42, 54 The information sources most often consulted by parents were friends or family, healthcare providers, as well as social media. These findings were in line with several studies, which found the importance of the role of healthcare providers, family, and relatives in the use of CAM, especially in pediatric patients. It showed the importance of communication skills of healthcare providers with parents for the proper use of CAM in their children.55-57

Parental delays in childhood cancer are closely related to parental health-seeking behavior. Parents are the individuals who first notice a physical or behavioral change in their children and initiate the diagnostic childhood pathway, so their perspective and behavior, especially in health-seeking behavior, will affect the interval of diagnostic triage.58 Our findings from the theoretical framework described the concept of the determinant of parental use of CAM, which includes vague initial childhood cancer symptoms, parental seeking behavior, CAM availability/accessibility, and barrier of healthcare facilities, could be classified as internal and external factors.59 This model was partly in concordance with Andersen's socio-behavioral model (SBM), which covered predisposing factors, enabling factors, need factors, and healthcare experience.57 Parental-seeking behavior was determined by parental fright and worries, sociocultural beliefs, and disease perception.

Our results suggest an effect of older Indonesian parents who still believe in CAM compared to modern medicine. There is a strong influence of culture and ancestral beliefs in Indonesian society. It allows older parents to prefer to use CAM first rather than directly taking the patient to the nearest health facility.60 For centuries, CAM, which was originally based on religious values, has been a common practice inside Indonesia and is still fully integrated into the daily lives of different generations of Indonesian people. Consultations with a shaman (men who can communicate with spirits or divine creatures) and herbal medicine are widespread.61 Cultural beliefs also favored traditional remedies or CAM. These practices have been passed down for generations, and this embedded culture cannot be ignored. People perceived that biomedicine was failing to cure illness; fear of side effects, dependence on medication, and medical procedures were other common reasons cited for using traditional or alternative treatments. Indonesians regard and perceive traditional remedies as safe because they are made from natural resources.

Parental fright and worries about less severe symptoms of childhood cancer contribute to self-medication practice, which is a very common practice in many developing and underdeveloped countries where without consulting a doctor or pharmacist, they handle or treat their illness by themselves.62 In Indonesia, the overall prevalence of self-medication observed is 58.82% in under-5 children by their mothers. A significant proportion of individuals handle or treat their illnesses.63 This condition additionally supported the accessibility of CAM in developing countries. As with many developing countries, most prescription medicines are available over the counter, including CAM remedies.59 Although parents' motivation to use CAM may be justified, our study illustrates that it was associated with significant delays in seeking conventional care. This may lead to cancer progression during the delay and reduced chances of survival.

Better accessibility of health facilities improved with 98.3% of patients having health insurance, although they got insurance after the patient was suspected of having childhood cancer, 54.7% of fathers and 51.3% of mothers having high education, and 64.9% having a distance 2 km or less to the nearest primary health facility, higher than other LMIC. This result may be due to this study being conducted on the island of Java, which has more health facilities even in rural areas.33 People can easily find private and public health facilities. However, this hypothesis has not been supported by publications or accurate reporting of how many pediatric cancer patients are untreated in our setting. However, still, some of the parents are reluctant to use healthcare facilities as their primary attempt due to negative parental perceptions regarding the quality of healthcare and national insurance. Our additional finding from qualitative data found that COVID-19 pandemic affected healthcare facility accessibility due to lockdown and lack of family and community support groups.64

Certain limitations of this study need to be addressed. First, the cross-sectional study design may have potentially biased our results because of wide confounding factors, such as the high proportion of nonresponder subjects and recall bias. We attempted to achieve accuracy by reviewing the dates of referral letters in the patient registry that input patient data in a prospective manner. Second, the small sample size of specific variables precluded comparing the differences in sociocultural characteristics. The current study of people's health-related behavior is made more complex due to it being a multicultural, ethnically diverse country, with a variety of healthcare providers. Unfortunately, this study was conducted in West Java Province, with the dominant influence of mostly Sundanese culture. Despite these limitations, our study also has some advantages. The study sample is representative of the population that had pediatric cancer because all the treated patients were registered at the IP-CAR, the one reference pediatric cancer center in the province. As such, our results could be generalized to the entire population of West Java. Based on the findings of our study, we recommend increasing knowledge and awareness regarding the signs and symptoms of childhood cancer in the population of developing countries and making a consensus on the more precise time or delays of each symptom. The strength of this study is its focus on patient delays during the COVID-19 period and time of data recruitment was at initial presentation of patients in the hospital, and prospective follow-up until the diagnosis was established. Further study of these issues may guide the development of appropriate interventions aimed at detecting symptomatic childhood cancer during its earliest stages, thus possibly improving the subsequent survival rate.

5 CONCLUSION

Our results demonstrate that a significant proportion of patients had delays that exceeded the suitable range. The type of cancer and use of CAM are the essential factors causing patient delay, more than socioeconomic factors. The determinant parental factor using the CAM includes parental seeking behavior, the vagueness of initial patient symptoms, CAM availability/accessibility, and the barrier of healthcare facilities. These are the important non-biology factors that can be improved and included in community childhood cancer awareness education in LMICs.

ACKNOWLEDGMENT

The authors would like to acknowledge My Child Matters Program for Sanofi Pasteur for support and the grant for the Indonesian Pediatric Cancer Registry. The authors alone are responsible for the content and writing of the paper.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST

The authors declare that there is no conflict of interest.