β-Thalassemia major births after National Screening Program in Taiwan

Abstract

Objective

A National Thalassemia Screening Program was adopted in Taiwan in 1993. This report examined that program's results and impact.

Methods

Patients with β-thalassemia major born between 1994 and 2003 were recruited through the help of all thalassemia clinics in Taiwan. A structured questionnaire was designed to collect the reasons for affected births.

Results

There were 97 affected births from 1994 to 2003.These births resulted after informed choice (n = 4), screening problems (n = 83), and undetermined causes (n = 10). Approximately 83% (5/6) of affected births in 2003 came from interracial marriages.

Conclusions

This report has identified several areas that might improve the thalassemia-screening program, including carrier screening in high school rather than in early pregnancy and the involvement of genetic counselors, providing care of new female immigrants. Pediatr Blood Cancer 2008;50:58–61. © 2007 Wiley-Liss, Inc.

INTRODUCTION

The two important forms of thalassemia, α- and β-thalassemia, are recognized as the most common monogenic diseases in the world 1. They are widespread throughout the Mediterranean region, the Middle East, the Indian subcontinent, and Southeast Asia including Taiwan. Approximately 1.67% of the world's population is heterozygotic for either α-thalassemia or β-thalassemia 2. In Taiwan's population of over 22 million people, approximately 5% are carriers for α-thalassemia (4% for α-thalassemia-1 and 1% for α-thalassemia-2 3, 4) and 1.1% for β-thalassemia 5, 6. β-thalassemia major patients are born healthy; however, symptoms, such as anemia, hepatosplenomegaly, growth retardation, jaundice, and bone changes, usually develop within the first year of life, thus making regular transfusion and iron chelation therapy necessary for survival. These diseases and their treatments impose significant burdens on patient health as well as psychosocial and economic burdens on the patients, their families, and society. Bone marrow transplantation and cord blood transplantation, the only available definitive cures for β-thalassemia major, are possible only in the limited proportion of patients having an HLA-matched donor. Given the high prevalence of thalassemia and the successes of thalassemia screening programs in several Mediterranean countries 7-9, the Taiwanese government adopted a National Thalassemia Screening Program in 1993. The purpose of the program was to prospectively identify affected babies, offer parents an opportunity to have a disease-free family through prenatal counseling and termination of pregnancy.

METHODS

Current Protocol for β-Thalassemia Screening

A program for the prevention of thalassemia has been in operation in Taiwan since 1993. The screening program is not mandatory, but it is combined with the first antenatal examination to facilitate the participation of pregnant women. These women have a blood sample tested for hemoglobin level and mean corpuscular volume (MCV) as part of the prenatal routine blood investigations, and if the complete blood count (CBC) of the pregnant woman reveals a low MCV (<80 fl) or a low mean corpuscular hemoglobin (MCH) (<25 pg), testing of the male partner follows. If both partners have microcytosis or hypochromia, they are referred to a confirmation center. In the confirmation test, the serum ferritin concentration, Hb A2, and Hb F levels are determined. To rule out iron deficiency anemia, a transferrin saturation test is performed. Subjects with a normal Hb A2 (<3.5%), but low ferritin concentration and/or transferrin saturation, are treated with iron therapy first, followed by a repeat CBC 4 weeks later, before further investigations on their thalassemia status are conducted. We expect an increase in their Hb by 1 g/dL and an increase in MCV after a 4-week iron therapy course. In the presence of a normal Hb A2 (<3.5%) and normal ferritin concentration and/or transferrin saturation, we manage the females or their partner as a suspected α-thalassemia carrier. In subjects with a raised Hb A2 (<3.5%) and/or Hb F concentrations, the four common β-thalassemia mutations (IVS-II-654 (C→T), CD41/42 (-TCTT), -28 (A→G), and CD17 (A→T)) are first screened for. If no positive results are obtained, DNA sequencing is performed using polymerase chain reaction (PCR)-based techniques. If couples are identified to be β-thalassemia carriers, DNA diagnosis for the fetus by chorionic villus sampling (CVS), amniotic fluid sampling, or fetal blood sampling is performed. If prenatal testing shows that the fetus is affected, the option of termination of pregnancy is offered to the parents. To facilitate participation in the screening program, the above-mentioned tests (excluding DNA analysis) have been covered by the National Health Insurance since May 1995; however, the DNA analysis is only partly subsidized by the government and families need to pay only S50-US amount.

Recruitment of Patients With β-Thalassemia

Patients with β-thalassemia major born after 1994 were recruited through the assistance of thalassemia clinics throughout the whole country, including, National Taiwan University Hospital, Tao-Yuan General Hospital, Chang Gung Children's Hospital, Mackay Memorial Hospital, China Medical University Hospital, Kaohsiung Medical University Hospital, Chang Gung Memorial Hospital (Kaohsiung branch), Chang-Hua Christian Hospital, Tri-Service General Hospital, Buddhist Tsu Chi General Hospital, National Cheng Kung University Hospital, Taipei Veterans General Hospital, and Taichung Veterans General Hospital.

Data Collection

A structured questionnaire was designed to collect the clinical data, and reasons for birth of affected patients. Primary data were collected through the assistance of pediatric hematologists at thalassemia clinics, and reconfirmed with parents by either face-to-face or telephone interview.

DNA Analysis

DNA was extracted from peripheral blood leukocytes using standard procedures, and genomic DNA was amplified by PCR. DNA molecular investigations were performed by denaturing high-performance liquid chromatography (DHPLC) 10 and confirmed by direct sequencing.

RESULTS

β-Thalassemia Major Births After Initiation of The National Screening Program

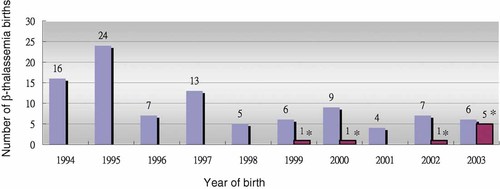

A total of 97 patients with β-thalassemia major were born from 1994 to 2003. The number of affected births per year is shown in Figure 1. The number of β-thalassemia births reached its highest level at the beginning of the National Screening Program (16 in 1994 and 24 in 1995) and decreased to less than 10 after 1998.

The number of β-thalassemia births decreased significantly after 1995. *β-Thalassemia births from interracial marriage have occurred since 1999. Five out of six patients born in 2003 came from interracial marriage, of whom, two were born despite the parents knowing they would have β-thalassemia major. [Color figure can be viewed in the online issue, which is available at www.interscience.wiley.com.]

Reasons Accounting for β-Thalassemia Births After Initiation of the National Screening Program

Four patients were born after parents were informed of their choice. Three patients were born because mothers did not receive antenatal examinations. The remaining patients were related to problems in the screening procedures including: (a) failure to detect parental risk (54/97); (b) referral problems (12/97); (c) laboratory problems (14/97); (d) unknown (Table I). Among patients born due to failure to detect parental risk, inaccurate hematologic studies, or incorrect interpretation of the CBC data by physicians) were in part responsible. Among patients with referral problems, five couples refused further prenatal diagnosis; wrong referral or late referral were also causes. The time-consuming procedure of our screening program and the lack of time for sharing relevant medical information with the parents on the part of physicians might have also contributed to this problem. Among the patients with laboratory problems, 2 couples had normal hematologic studies, and the other 12 were related to laboratory errors.

| Reasons for β-thalassemia births | Case number |

|---|---|

| Born after informed choice | 4 |

| Mother not screened | 3 |

| Failure to detect parental risk | 54 |

| Referral problems | 12 |

| Refusal of prenatal diagnosis | (5) |

| Wrong referral | (2) |

| Late referral | (5) |

| Laboratory problems | 14 |

| Laboratory errors | (12) |

| Normal parental hematologic studies | (2) |

| Unknowna | 10 |

- a The reasons for β-thalassemia births were unknown in 10 patients. One was dead, and we did not contact the family due to ethical consideration. The others could not be reached during the study period.

Impact of Interracial Marriage on β-Thalassemia Major

The number of babies born to interracial marriages has increased steadily in Taiwan (Table II). Eight out of 97 affected births were born to interracial marriages, and 5 of 6 affected births in 2003 came from interracial marriages. Among these eight affected births, one was born to a Chinese mother and two were born to Indonesian mothers. IVS-I-5 (G→C) mutation was identified in one child and his Indonesian mother 12; this was the first such mutation report in Taiwan. The mother did not receive antenatal examinations while she was pregnant. The remaining five babies were born to Vietnamese mothers. Four had E/β-thalassemia, and one had homozygous IVS-II-654 (C→T) mutations. All these five Vietnamese females received regular antenatal examinations and two births came after the parents knew that their babies would have β-thalassemia major.

| Year | Number of live births | Live births born to interracial marriages | % |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1999 | 283,661 | 17,156 | 6.05 |

| 2000 | 305,312 | 23,239 | 7.61 |

| 2001 | 260,354 | 27,746 | 10.66 |

| 2002 | 247,530 | 30,833 | 12.46 |

| 2003 | 227,070 | 30,348 | 13.37 |

| Total | 1,323,927 | 129,322 | 9.77 |

DISCUSSION

Testing for heterozygosity during pregnancy and in other settings has led to a marked reduction in the frequency of thalassemia major in several Mediterranean countries and Montreal 13, 14. Taiwan consequently developed the Taiwan National Thalassemia Screening Program.

Although affected births have decreased, there were still 97 β-thalassemia births between 1994 and 2003. We found the most important and preventable cause for affected births was failure to detect parental risk. The screening protocol in Taiwan requires CBC testing for the pregnant woman followed by testing of her partner. In addition, if iron deficiency anemia is suspected, a 4-week treatment with iron before further investigation is needed. Experience in Montreal showed all the carriers identified in the high-school screening program remembered their status, and took part in various options for reproductive counseling/prenatal diagnosis later in life. Hence, in the future, a well-planned education and thalassemia-screening program for high school students might be a better approach in which to identify individuals at risk.

After identifying individuals at risk, well-trained genetic counselors should confidentially inform these carriers about their test results and give relevant medical information to them. Under certain conditions, the genetic counselors could help at-risk individuals to make informed decisions about reproductive options and to obtain prenatal diagnosis 14. Training for genetic counselors in Taiwan is now underway. Though this is not for thalassemia only, it is a good beginning toward further improvement in the thalassemia-screening program.

Interracial marriage, involving females from China, Thailand, Vietnam, Indonesia, and Cambodia has increased during the last dozen years. A total of 224,196 female immigrants were living in Taiwan in interracial marriages at the end of August 2003 15. They have changed the epidemiology of thalassemia 16. Despite most E/β-thalassemia being traditionally classified into thalassemia intermedia, the clinical manifestations are diverse. Our patients were transfusion-dependent. This is the reason why we have included Hb E in our screening program.

We were concerned about the limited availability of antenatal examinations in the families of interracial marriage because most of them belonged to a lower socioeconomic class. National Health Insurance does not cover females from interracial marriage until they reside in Taiwan more than 4 months. The Taiwan government has recently begun paying attention to new immigrants in interracial marriages, and declared that these daughters-in-law have contributed to the creation of a new generation. As well as an educational program for female immigrants in primary schools, the government has decided to provide immigrant female spouses with an allowance (US$ 20) for each of five antenatal examinations since March 31, 2005 17.

The rate of laboratory errors was relatively high when compared with that of another report 11. Despite the 4 most common mutations account for more than 90% of mutant alleles 18, 23 β-thalassemia mutations have been detected in Taiwan, of which 19 have been found in patients with β-thalassemia major. These rare mutations have made carrier detection and prenatal diagnosis difficult 12, 19. New advances in DNA testing might overcome this problem. DHPLC has been found to be a very useful tool in detecting β-thalassemia mutations in Taiwan 10. Recent studies using microarray technology showed promising results in thalassemia mutation detection 20, 21. All these technological advances should further strengthen the screening program.

Acknowledgements

We are grateful to the following doctors for helping to collect data on patients: Chang Gung Children's Hospital: Dr. Tang-Her Jiang, Dr. Chao-Ping Yang, Dr. Iou-Jih Houng. Mackay Memorial Hospital: Dr. Lin-Yen Wang, Dr. His-Che Liu, Dr. Der-Cherng Liang. China Medical University Hospital: Dr. Kang-Hsi Wu, Dr. Ching-Tien Peng. Kaohsiung Medical University Hospital: Dr. Ren-Chin Jang, Dr. Tai-Tsung Chang. Chang Chang Gung Memorial Hospital, Kaohsiung branch: Dr. Jiunn-Ming Sheen, Dr. Chih-Cheng Hsiao. Chang-Hua Christian Hospital: Dr. Shih-Shung Wang, Dr. Ming-Tsan Lin Tri-Service General Hospital: Dr. Chun-Jung Chen, Dr. Shin-Nan Cheng Buddhist Tsu Chi General Hospital: Dr. Rong-Long Chen. National Cheng Kung University Hospital: Dr. Chao-Neng Cheng, Dr. Jiann-Shiuh Chen. Taipei Veterans General Hospital: Dr. Yuh-Lin Hsieh. Taichung Veterans General Hospital: Dr. Te-Kau Chang. We thank Professor Tsang-Ming Ko for his insightful comments. This work was partially supported by the Taiwan Foundation for Rare Disorders.