NO CHILD LEFT BEHIND: A DEEPLY FLAWED FEDERAL POLICY

[The copyright line for this article was changed on 7 February 2018 after original online publication.]

No Child Left Behind (NCLB), the 2001 reauthorization of the Federal Elementary and Secondary Education Act, represented a sea change for the federal government's role in k-12 education, a function reserved by the U.S. Constitution for the states. Prior to that year, the federal government had relied primarily on the equal protection clause of the Constitution to promote educational opportunity for protected groups and disadvantaged students and had done so in part with Title 1 grants to schools serving low-income students. Although it accounted for only 1.5 percent of school budgets in 2000, Title I funding served as the mechanism for the federal government to use NCLB to put pressure on all individual schools throughout the country to raise student achievement. While a state could have avoided the pressure of NCLB by foregoing its share of Title 1 funds, none chose to do so.

Under NCLB, the federal government required all states to test every student annually in Grades 3 through 8 and once in high school in math and reading and to set annual achievement goals so that 100 percent of the students would be on track to achieve proficiency by 2013/2014. Each school was required to make adequate yearly progress (AYP) toward the proficiency goal and was subject to consequences if it failed to do so. This AYP requirement applied not only to the average for all students in the school, but also to subgroups defined by economic, racial, and disability characteristics. Consistent with our federal system, states were to use their own tests and to set their own proficiency standards. The act also required that all teachers of core academic subjects be highly qualified, defined as having a Bachelor's degree and subject-specific knowledge.

This bipartisan act represented a response to three types of concerns, starting with the view, embedded in the standards-based reform movement (O'Day & Smith, 1993) that this country needed higher and more ambitious standards for students who would be competing in an increasingly global and knowledge-based society. The other concerns related to purported inefficiencies in the U.S. education system and concern within the civil rights community about huge disparities in educational outcomes across groups defined by race or income. I return to these concerns below with my overall evaluation of NCLB. First, though, I turn to the question of how NCLB affected student outcomes.

IMPACT OF NCLB ON STUDENT ACHIEVEMENT

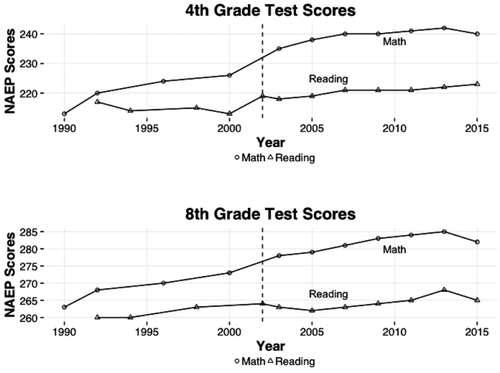

Proponents expected NCLB to boost student achievement overall and to reduce gaps between disadvantaged student subgroups and their more advantaged counterparts. The National Assessment of Educational Progress (NAEP), often referred to as the Nation's Report Card, provides a natural set of test scores for measuring such outcomes. These tests have been given to nationally representative random samples of fourth and eighth graders throughout the country since the early 1990s. NAEP scores are comparable for students across the country, and, unlike high stakes tests at the state level, are not susceptible to teaching to the test.1

Figure 1 documents the trends in 4th- and 8th-grade test scores in math and reading over time. The dashed vertical line denotes the year NCLB was adopted. Although both 4th- and 8th-grade math test scores rose in the post-NCLB period (until 2015), for the most part they simply continued the upward trend that had begun in the 1990s. Moreover, reading scores declined in the first few years of the post-NCLB period. Thus, these trends provide little or no support for the hypothesis that NCLB raised test scores.

Of course, these trends alone do not account for what would have happened in the absence of NCLB. Moreover, since it applied to all schools throughout the country and was introduced at a single point in time, there is no obvious control group to which one can compare the outcomes for those subject to NCLB. Different groups of researchers have used a variety of methods to explore the causal impacts.

The best-known studies are by Dee and Jacob (2010, 2011). To isolate the causal effects of NCLB, they make use of the fact that some states had introduced their own accountability systems in various years prior to the introduction of the national program. They view states that had no prior accountability system as the group that was treated by the federal law, with the others serving as the control group. The authors then estimate interrupted time series models that allow them to test for changes in the trend in the treated states in the post-NCLB period.2

From these analyses, they conclude that NCLB led to a moderate and statistically significant increase in test scores in math for 4th-grade students and a positive, but not statistically significant, increase for eighth graders in math, with no effects on reading scores for students in either grade. Additional analysis for 4th-grade math scores shows that the effects were largest at the bottom of the test score distribution, suggesting that NCLB was most effective in improving basic skills. They also find some positive effects by subgroup. Reporting results only for math test scores, the authors find moderately large positive effects for blacks in 4th-grade math, and positive effects in both grades for Hispanics and students from low-income families (Dee & Jacob, 2010, Table 2).

Despite the high quality of the Dee and Jacob research, they may have overstated the positive impact on 4th-grade math scores. It seems odd, for example, that the biggest test score gains in 4th-grade math show up in the NAEP scores of 2003, the first year of NCLB. Given the challenges of implementing a new program and the fact that education is a cumulative process, with outcomes in Grade 4 dependent in part on prior year achievement, any gains in 2003 seems far too early to attribute to NCLB. Not surprisingly, if that year is eliminated from the Dee and Jacob's empirical analysis, the finding of a statistically significant effect in 4th-grade scores disappears (Ladd, 2010).

Other researchers come to quite similar conclusions. Building on the Dee and Jacob methodology, but with attention to the fidelity with which NCLB was implemented by individual states, Lee and Reaves (2012) find no significant effects that can be attributed to the law on either overall achievement in reading or math or on achievement gaps. Using a very different approach that focuses on the pressure schools face when they are in danger of failing and measuring achievement by low stakes test results from national ECLS surveys rather than the NAEP, Reback, Rockoff, and Schwartz (2014) find small positive effects in reading scores, but no statistically significant effects on math or science scores during the first 2 years of NCLB.

The overall test score effects of NCLB are clearly disappointing. Moreover, its positive effects on certain subgroups in some grades and subjects were far from sufficient to move the needle much on test score gaps. Such gaps in NAEP scores remained high in 2015.

BROADER EVALUATION OF NCLB

Although NCLB included some components that generated positive, if qualified, effects, my overall conclusion is that NCLB was deeply flawed.

Positive Components

Perhaps the most positive aspect of NCLB is that it generated huge amounts of data on student achievement in math and reading. The availability of rich data on all tested students, not just samples of students, has been a bonanza for educational researchers and policymakers alike. It is hard to overstate the significance for researchers in specific states of having test score data for all tested students that can be matched over time to other educational data on teachers and schools and that can be matched in some states to other large data sets such as those on vital statistics, higher education, and labor market outcomes. Researchers connected with the Center for the Analysis of Data in Education Research (CALDER), for example, have used such data from several states to generate about 170 papers since 2006 (Caldercenter.org).3

A second positive component of NCLB, especially in the eyes of civil rights groups, is that schools are held accountable not only for the aggregate test scores of their students but also for the average test scores of subgroups of students whom they might otherwise ignore. One possible problem, though, is that individual schools may not be the appropriate unit of accountability for subgroup performance. Students in the designated categories can still be ignored when there are too few of them in individual schools. Moreover, individual schools have fewer policy levers for improving the performance of subgroups than policymakers at the district level who set the rules under which students and teachers are allocated among schools and make decisions about the resources available to individual schools. Hence, accountability for the performance of subgroups may be better placed at the district level.

A third arguably positive element of NCLB was its requirement that all teachers be “highly qualified.” Although many states initially dealt with this requirement by developing their own measures of quality, by 2006 all states had official requirements for teacher quality that complied with the law, and 88 percent of school districts reported that all teachers of core subjects would be “highly qualified” as defined by NCLB (Jennings & Rentner, 2006). The provision appears to have provided a floor on teacher quality by contributing to a dramatic reduction in the reliance on uncertified teachers (Loeb & Miller, 2006). Although not required by the act, NCLB apparently led to a higher proportion of teachers with Master's degrees (Dee & Jacob, 2010). Debate remains, however, about the usefulness of Master's degrees, especially those attained after a teacher enters the profession (Ladd & Sorensen, 2015).

Flaws of NCLB

Despite these positive elements, the law's use of top-down accountability pressure that was more punitive than constructive represents a flawed approach to school improvement. Three specific flaws deserve attention.

Its Narrow Focus

An initial problem with the test-based accountability of NCLB is that it is based on too narrow a view of schooling. Most people would agree that aspirations for education and schooling should be far broader than teaching children how to do well on multiple-choice tests. A broader view would recognize the role that schools play in developing in children the knowledge and skills that will enable them not merely to succeed in the labor market but to be good citizens, to live rich and fulfilling lives, and to contribute to the flourishing of others (Brighouse et al., 2016).

Research both on NCLB, as well as some of the state-specific accountability programs that preceded it, has shown it has narrowed the curriculum by shifting instruction time toward tested subjects and away from others. A nationally representative survey of 349 school districts between 2001 and 2007 shows that schools raised instructional time (measured in minutes per week) in English and math quite significantly while reducing time for social studies, science, art and music, physical education, and recess (McMurrer, 2007; also see National Surveys by the Center on Education Policy; Byrd-Blake et al., 2010; Dee & Jacob, 2010; Griffith & Scharmann, 2008). This narrowing of the curriculum undermines the potential for schools to promote other valued capacities, such as those for democratic competence or personal fulfillment.

Further, NCLB has led to a narrowing of what happens within the math and reading instructional programs themselves. That occurs in part because of the heavy reliance on multiple-choice tests that are cheaper and quicker to grade than open-ended questions that would better test conceptual understanding and writing skills. In addition, test-based accountability gives teachers incentives to “teach to the test” rather than to the broader domains that the test questions are designed to represent. Evidence of teaching to the test emerges from the differences in student test scores on the specific high stakes tests used by states as part of their accountability systems, and test scores on the NAEP, which is not subject to this problem (see Klein et al., 2000, for a comparison of Texas test scores on NAEP and the Texas high stakes tests).

NCLB also encouraged teachers to narrow the groups of students they attend to. Various studies document, for example, that the incentive for teachers to focus attention on students near the proficiency cut point has led to reductions in the achievement of students in the tails of the ability distribution (Krieg, 2008; Ladd & Lauen, 2010; Neal & Schanzenbach, 2010).

Unrealistic and Counter-Productive Expectations

A second flaw is that NCLB was highly unrealistic and misguided in its expectations. Even if we set aside its 100 percent proficiency goal as aspirational rhetoric, the program imposed counter-productive expectations in a variety of ways.

Recall that one of the goals of NCLB was to raise academic standards throughout the country. Given that the U.S. lodges responsibility for education at the state level, federal policymakers had to permit individual states to set their own proficiency standards. The accountability provisions of the law meant, however, that if a state chose to raise its standards without providing the additional resources and support needed to meet those standards, the result would be greater numbers of failing schools. Hence, it is not surprising that instead of states raising their proficiency standards, some states reduced them. Among the 12 states for which they had data starting in 2002/2003, Cronin et al. (2007) found that seven had lowered their proficiency standards by 2006 and declines were largest in states that had the highest initial proficiency standards. The authors also found a huge amount of variance between states in the difficulty of their proficiency standards.

The program was unrealistic as well in that many schools simply could not meet the requirements of AYP and hence were named and shamed as failures and made subject to sanctions. This requirement differed across schools and states depending on the state's proficiency standards and the timetable it set out for the schools to meet the goal by 2013/2014. In many cases, states defined the time path so that it would be more feasible to meet in the early years than in the later years. The net effect was a rising failure rate over time. By 2011, close to half of all schools in the country were failing, with the rates well over 50 percent in some (Usher, 2015). Something is clearly amiss when half of the objects of accountability, in this case individual schools, are not in a position to succeed.4

With Congress not able to reach consensus on how to modify or update ESEA between 2007 and 2015, the requirements of NCLB remained in force, leading to the untenable situation in which most schools would eventually be failing. To avoid this situation, the Obama administration intervened in 2011 by offering waivers from certain requirements of NCLB to states that requested them. A key element of the waiver agreements was a shift of focus of accountability away from test score levels to a greater focus on the growth in student test scores or progress in reducing achievement gaps. While this shift represents a sensible change, it did little to counter the narrow focus and top-down nature of NCLB. By 2015, 43 states had received waivers from the most stringent provisions of NCLB (Polikoff et al., 2015). Although the waivers were necessary to stop the rise of school failures, the fact that the Obama administration had to work outside the Congress is another undesirable outcome in that it sets a bad precedent for future policymaking.

A final counterproductive effect of NCLB has been its adverse effect on teacher morale and the harm it could be doing to the teaching profession. Although researchers and policymakers frequently point to teachers as the most important school factor for student achievement, evidence shows that NCLB has reduced the morale of teachers, especially those in high poverty schools (Byde-Blake et al., 2010). Further, clear evidence of cheating by teachers in some large cities, including Atlanta, Chicago, and Washington, DC, even if limited to small numbers of teachers, indicates the magnitude of the pressures facing some teachers under high stakes accountability of the type imposed by NCLB. Low teacher morale matters in part because it may well increase teacher attrition. Although we do not have much direct evidence on how NCLB affects attrition, we do know that the approximately 8 percent attrition rate of teachers in the United States is far higher than that in many other countries (Sutcher, Darling-Hammond, & Carver-Thomas, 2016) and that reducing the rate would substantially mitigate concerns about projected teacher shortages and the costs of teacher turnover.

Pressure without Support

A third major flaw is that NCLB placed significant pressure on individual schools to raise student achievement without providing the support needed to assure that all students had an opportunity to learn to the higher standards. In this way, NCLB included only one part of what the standards-based reformers had initially intended to be a much more comprehensive package. That package would have started with high and ambitious standards for students but would have paid attention to the capacity of teachers to deliver an ambitious curriculum and to the availability of the resources required to assure that all children had an opportunity to learn to the high standards.

NCLB relied instead almost exclusively on tough test-based incentives. This approach would only have made sense if the problem of low-performing schools could be attributed primarily to teacher shirking, as some people believed, or to the problem of the “soft bigotry of low expectations” as suggested by President George W. Bush. But in fact low achievement in such schools is far more likely to reflect the limited capacity of such schools to meet the challenges that children from disadvantaged backgrounds bring to the classroom. Because of these challenges, schools serving concentrations of low-income students face greater tasks than those serving middle class students. The NCLB approach of holding schools alone responsible for student test score levels while paying little if any attention to the conditions in which learning takes place is simply not fair either to the schools or the children and was bound to be unsuccessful.

To be sure, districts or states could have responded by providing more support services. In fact, under NCLB when a school failed to meet AYP 2 years in a row, the district was required to pay for supplementary services for the school's students. But studies show that such services were generally of low quality, and were not extensively used (Heinrich, Meyer, & Whitten, 2010; Muñoz, Potter, & Ross, 2008). In addition, state governments could have responded to the federal policy by developing the capacities of their school systems, and some did to a limited extent. The study by Dee and Jacob mentioned earlier found that states responded to NCLB by increasing per pupil spending by $570 dollars per pupil, with this investment coming in a combination of increases in teacher salaries and other non-teacher investments (Dee & Jacob, 2010). Importantly, though, the authors found no evidence of an increase in federal funding for education.

Far more resources and attention to capacity building would have been helpful for many of the low-performing schools. But more generally a “broader and bolder” approach to education, one that addresses the challenges that many disadvantaged children bring to school, was needed. Such an approach would include high-quality pre-school, better health services, and more high-quality afterschool and summer programs of the type that children from middle class families take for granted (Ladd, 2012; also see boldapproach.org).

WHAT CAN WE EXPECT FROM ESSA?

In December 2015, Congress finally managed to reauthorize the Elementary and Secondary Education Act and to replace its NCLB requirements with a new set of provisions, labeled the Every Student Succeeds Act (ESSA). Under this new law, states are still required to test all students in math and reading and to disaggregate results by subgroup (albeit a slightly different set of groups). The main change is that state governments will have primary responsibility for designing and enforcing their own accountability systems but will still be subject to some federal regulations. All states, for example, must include a non-test measure of school quality or student success. The transition to the new state plans is now in progress with full implementation occurring in the 2017/2018 school year.

It is far too early to predict with any confidence what the states will do and with what effects. The most plausible prediction at this point is that the variation across states is likely to be large. That variation will reflect the differing capacities of State Boards of Education, differing revenue-raising capacities across states, and differing commitments to the development of comprehensive new systems that build in support as well as accountability. The federal government will still have a role to play, but we can only hope that its role will be far more positive and constructive than it has been under NCLB.

ACKNOWLEDGMENT

Corey Vernot of Duke University provided excellent research support for this essay.

Biography

HELEN F. LADD is the Susan B. King Professor of Public Policy and Economics, Sanford School of Public Policy, Duke University, Durham, NC 27708 (e-mail: [email protected]).