The Effect of the Child Support Performance and Incentive Act of 1998 on Rewarded and Unrewarded Performance Goals

Abstract

This paper examines the impact of the Child Support Performance and Incentive Act (CSPIA) of 1998 on child support performance measures that are rewarded financially as well as outcomes that are not rewarded. Three of the five performance measures explicitly rewarded by CSPIA are reconstructed in this analysis, as are two child support outcomes that were considered for financial rewards but were ultimately rejected. Using a panel interrupted time series model with state fixed effects and state-specific trends, this analysis finds that CSPIA had a statistically positive impact on just one rewarded performance goal, cost-effectiveness, and negatively impacted an unrewarded child support outcome—collections sent to other states. Effect sizes suggest that CSPIA had little impact on child support performance, on balance. These results provide more evidence to the ongoing debate about the ability of performance incentives to improve public sector performance. It also suggests that reforming performance systems in response to perceived problems may create new gaming responses.

INTRODUCTION

The child support enforcement (CSE) system is one of the largest programs targeted at low-income families with children and has an important effect on household income (Pirog & Ziol-Guest, 2006).1 CSE is a unique cornerstone of the social safety net; rather than rely on direct expenditures, CSE leverages transfer payments from noncustodial to custodial parents. Because this support can prevent (or offset) government assistance, CSE enjoys a unique base of support. Evidence suggests that this support is critical—child support income makes up roughly 20 percent of total family income, conditional on any child support income (United States Census, 2014). In fiscal year 2014, $28.2 billion in child support was transferred from noncustodial parents to custodial families through the child support system, collecting five-and-a-quarter dollars in child support for every dollar spent by state and local governments. By comparison, combined spending on the National School Lunch and the School Breakfast Programs totaled $12.6 billion in FY2014 and expenditures on the Special Supplemental Nutrition Program for Women, Infants and Children totaled $6.2 billion (Oliveira, 2015).2 Child support is also increasingly important for growing single-parent families—40.2 percent of births in 2012 were to unmarried mothers, compared to 18.4 percent in 1980 (Hamilton et al., 2015).3 A significant number of child support cases go without collections—41.5 percent of cases had no collections in FY2012, representing billions of dollars in uncollected child support. This problem is more severe among households currently on public assistance—65 percent of those cases do not have any child support collections (Office of Child Support Enforcement [OCSE], 2016).

In 1998, the CSE system was dramatically changed by the Child Support Performance and Incentive Act (CSPIA), the incentive system in use today. The primary intent of CSPIA was to change the single (financially rewarded) performance goal, cost-effectiveness, to a five-factor system, adding four measures widely considered to be at the core of the CSE mission (Gardiner et al., 2003). The new performance measures included paternity establishment performance, child support order establishment performance, collection of current child support, and collection of past-due child support. The system also retained a modified version of cost-effectiveness. Performance on the five measures was linked to sizable incentives payments.

This paper evaluates the impact of CSPIA both on the explicit performance measures and on potential unintended consequences resulting from gaming behavior. In previous research, Huang and Edwards (2009) found that CSPIA substantially improved child support outcomes but did not examine unintended consequences or gaming behavior. Performance systems explored in Courty and Marschke (2003) and Heinrich and Marschke (2010), among others, suggest that performance incentive systems are highly susceptible to such behaviors.

Results from this analysis suggest that CSPIA has had little impact on CSE performance; two of the explicit performance measures increased modestly after CSPIA, while one of the child support outcomes considered for performance reward (but rejected) saw a substantial decline, suggesting a gaming response. This suggests that CSPIA was not a notable improvement over the preceding incentives regime.

Unfortunately, it was not possible to collect systematic data on how states used performance information in this time period. Previous empirical literature suggests that both why and how organizations use performance information matters greatly to performance outcomes (Gerrish, 2016; Moynihan & Ingraham, 2004; Moynihan & Pandey, 2010). This results in a black-box evaluation of CSPIA, a high-powered incentives system with significant financial rewards and penalties. Whether changes in performance information use mediated the impact of CSPIA is difficult to evaluate with the data available.

The rest of this paper is organized as follows: the next section describes the CSE system and the performance incentives literature as well as two previous analyses of CSPIA. The following sections outline the measures and sources of the data used in this analysis and some of the difficulties in comparing child support outcomes before and after CSPIA. Next, I detail the empirical strategy, and present results of the baseline specification. Then robustness tests are conducted and the implications for policy and research are discussed, followed by concluding remarks.

POLICY ENVIRONMENT

While CSE activities are carried out by state and local child support officials, CSE policy is coordinated between states and the federal government. Nominally, states define who receives child support, the amount of the child support order, and how payments are to be collected. Since the 1970s, however, the federal government has used both carrots and sticks to craft a more homogeneous national CSE policy. State performance incentive payments, for example, are both carrot and stick. The federal government rewards states for pursuing national child support goals while punishing states for failing to improve on these goals, essentially through the loss of Temporary Assistance for Needy Families (TANF) block grant funding.

CSE actions are organized around cases—legal actions involving a custodial party (CP), their dependents, and a noncustodial parent (NCP) or putative father. Child support is enforced at the state and local levels by collecting money from NCPs and transferring it to CPs on behalf of dependent children. In order to do so, child support officials must first establish paternity of the child (in the most common scenario where the CP is the mother), and then establish a legal order for the NCP to pay child support. Orders may be amended to add back payments accruing from past nonsupport. Child support officials can also assist custodial parents who are not receiving their child support payments through a variety of tools, including parent location, wage withholding, and license revocation. Many families do not use the formal CSE system; they enter into informal arrangements or file their own arrangements with courts.

States are then rewarded financially by the federal government for performance on their caseload, or the total set of cases presented to them. The typical case is an unmarried white woman over the age of 30 with a single child, though African Americans and Hispanics are somewhat overrepresented as a share of the population (OCSE, 2016). The federal government rewards state and local governments through two primary mechanisms. First, the federal government provides 66 percent matching payments for most administrative expenditures. Second, the federal government disburses roughly $500 million each year to states based on annual caseload performance.4 The $500 million incentives fund comprises roughly 35 percent of all state and local child support spending, excluding federal matching payments (U.S. Government Accountability Office, 2011).5 Prior to the passage of CSPIA in 1998, states were rewarded from this fund for just one performance factor: total child support collected divided by total qualified administrative payments, known as the cost-effectiveness ratio (OCSE, 1997b).

The Personal Responsibility and Work Opportunity Reconciliation Act of 1996 (PRWORA) required that the secretary of the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services (HHS) recommend to Congress a new incentive funding system for CSE. This requirement was mandated after a number of organizations, such as the U.S. Commission on Interstate Child Support, National Conference of State Legislatures, American Public Welfare Association, and National Governor's Association, expressed concern about the current child support incentives system (OCSE, 1997b). Much of the criticism centered on the cost-effectiveness performance measure, arguing that it insufficiently addressed the evolving goals of the CSE system. In response to PRWORA, HHS formed the Incentive Funding Workgroup, consisting of 15 state and local child support directors and 11 federal representatives from HHS, largely from the OCSE. The Incentive Funding Workgroup published a report in January of 1997 proposing reforms that formed the underpinnings of the changes found in CSPIA. CSPIA changed the one-factor formula to a five-factor formula, adding (i) paternity establishment performance, (ii) child support order establishment performance, (iii) performance on collections of current support, and (iv) performance on cases paying toward past support, while maintaining a slightly modified version of the original performance factor: (v) cost-effectiveness. All four new goals are measured as percentages, although for accounting reasons some states can perform above 100 percent in some years. The new system was phased in over three years and was fully effective in FY2002 (U.S. Government Accountability Office, 2011).6

The Incentive Funding Workgroup also considered five other child support goals to be used as performance measures, but ultimately the workgroup rejected them as premature (Solomon-Fears, 2013). The alternative measures included medical support orders, collections sent to other states (interstate collections), welfare cost avoidance, payment processing performance, and customer satisfaction. In this paper, the child support goals explicitly rewarded by CSPIA are referred to as the performance measures while goals not rewarded are referred to as the alternative child support outcomes (or goals) to avoid potential confusion.

The calculation of each state's performance payment is complex, although it is important to at least outline here to understand potential gaming behaviors that may result from this particular structure of incentives. The amount of total incentives payments was capped by CSPIA, so states calculate a “hypothetical” child support incentive payment each fiscal year on the basis of their performance on the five performance measures. This amount is adjusted for the size of the state's collections base.7 The OCSE sums all hypothetical payments across states and distributes to each state its fraction of the real incentive fund. As an example, state X is entitled to $8 billion in hypothetical incentives payments resulting from a combination of its performance in the five child support goals and the size of its collections base. All other states simultaneously calculate their hypothetical incentive payments and OCSE sums these hypothetical payments nationally. If the total hypothetical incentive payments for all states and territories was $50 billion, state X would be entitled to 16 percent of the roughly $500 million incentives pool, or $80 million ($8b/$50b = 16 percent × $500m = $80m).

Additionally, all five child support performance measures also have performance ceilings and floors. If states perform at 80 percent or above of (real) performance, they are entitled to 100 percent of their hypothetical performance incentive payment.8 For paternity establishment and order establishment performance, the hypothetical performance payment is 0 percent if actual performance is less than 50 percent—a significant disincentive.9 Performance rewards are scaled such that performance between 79 and 80 percent receives 98 percent of the hypothetical performance payment, 78 to 79 percent receives 96 percent, and so on (OCSE, 2012).

CSPIA also made a number of other changes to child support policy. First, total performance payments were capped, increased from $422 million in FY2000 to $483 million in FY2008, and then pegged to inflation. The FY2010 payment was $504 million. Second, CSPIA requires that the incentive payment be reinvested by states into either the CSE program or an activity that would improve the child support program. The old incentive system allowed states to roll incentive payments into state general funds. Third, CSPIA requires that data from states are audited on an annual basis, meeting a 95 percent standard of reliability. States failing to demonstrate data reliability receive no incentive payment on the factor found unreliable and may face additional financial penalties. Finally, CSPIA formed the Medical Child Support Working Group to “identify impediments to the effective enforcement of medical support by state CSE agencies and recommend solutions to these impediments” (Ross, 1999, n.p.). The working group was created to design a medical child support performance measure. That measure was never created. However, CSPIA did make it easier to obtain health insurance by creating a National Medical Support Notice form to inform employers that their employee is required to provide health insurance to their noncustodial child(ren) (Pirog & Ziol-Guest, 2006).

A naïve examination of performance on the five performance measures after CSPIA suggests a significant improvement in many child support outcomes; performance in all five areas increased by an average of 10.5 percent between 2001 and 2010, with order establishment and cost-effectiveness experiencing the largest increases, at around 20 percent.10 Only paternity establishment declined, largely because (population-weighted) paternity establishment performance was already very high prior to CSPIA.11 These improvements give rise to “a general consensus that the CSE program is doing well” (Solomon-Fears, 2013, p. ii). However, this naïve examination ignores the trends in CSE outcomes prior to CSPIA; it is possible that these performance gains would have been achieved with or without passage of CSPIA. Moreover, performance measures have reached a plateau in the years since CSPIA—child support orders, for example, have experienced slight declines, especially when examining CPS-CSS survey data (Meyer, Cancian, & Chen, 2015).

Child Support Incentives As Performance Management

The CSPIA of 1998 is just one of the large number of policies aimed at improving public sector performance. As such, the impact of the policy falls within a larger literature on the impact of performance measurement/management on public sector performance. The modern incarnation of these policies is often given provenance in the 1970s, though there is evidence for use of performance information as early as 1903 (Williams, 2003).

At the federal level, there have been numerous policies designed at improving the performance of entirely federal agencies, including the Government Performance and Results Act (GPRA), passed by congress in 1993, followed by the Office of Management and Budget's Program Assessment Rating Tool (PART) in 2002, and the modernization of GPRA in 2010. While GPRA and PART were government-wide attempts at managing performance, there is a longer history of performance incentives in the federal departments and agencies, such as the Department of Labor's Job Training and Partnership Act of 1982. Performance rewards in child support began in 1975 and predate many other performance systems, but for whatever reason, the impact of performance rewards on child support outcomes have been largely left unexplored in the performance management literature.

The rise in the popularity of performance management in the last few decades is owed largely to its intuitive appeal—to be effective stewards of public resources, we ought to manage public agencies by measuring, then managing, public sector performance, a common refrain among early advocates (Wholey & Hatry, 1992, for example).12 However, a significant body of research has challenged performance management from a variety of perspectives, including the implicit (or explicit) values of performance management (Radin, 2006), subjectivity in interpreting performance information (Moynihan, 2008), unintended consequences (Heckman, Heinrich, & Smith, 2002; Heinrich & Marschke, 2010), and the less successful application of performance management in the public sector compared to the private sector (Hvidman & Andersen, 2014).

Performance management has been popularly defined as a “system that generates performance information through strategic planning and performance measurement routines and that connects this information to decision venues, where, ideally, the information influences a range of possible decisions” (Moynihan, 2008, p. 5). CSPIA generates performance information in the form of OCSE annual reports and, importantly, in the form of performance rewards. States and localities “[connect] this information to decision venues” in numerous ways. For example, Gardiner et al. (2003) note, “Interviews with local office supervisors indicated that many of them track the performance of individual workers on a monthly basis for all relevant indicators. One state, for instance, uses a ‘traffic light’ system to rank offices by each incentive measure: Red indicates below the minimum standard for payment; Yellow indicates below state goals but above the minimum; and Green indicates above the state goal. The officials hope this will create friendly competition among the local offices.” New York City even modeled its performance management after the “PerformanceStat” movement, holding monthly meetings to justify programmatic trends (Doar, Smith, & Dinan, 2013). However, states are likely heterogeneous in their willingness and ability to connect performance information to decision venues.

Implementation of CSPIA suggests a number of implications from the performance management literature. One would hypothesize that CSPIA ought to improve performance in the four new child support areas. This is both the global, theoretical intent of all performance incentive systems and the specific intent of this law. Unconditional improvements in child support performance after CSPIA would support this hypothesis, as does an earlier analysis of CSPIA (Huang & Edwards, 2009) that is discussed in greater detail below. However, recent findings of a meta-analysis find no effect or a small positive effect of performance management on performance (Gerrish, 2016). It is still a very open question in this literature whether performance management is empirically correlated with organizational performance.

The impact of CSPIA on the retained performance measure, the cost-effectiveness ratio, is ambiguous. Total collections (the numerator of the ratio) appear in two other performance measures. Thus, increasing current or arrears collections will have an indirect positive effect on cost-effectiveness. Administrative expenditures (the denominator) may increase if states increase expenditures to improve in the four newly rewarded measures. This would have a negative effect on the cost-effectiveness ratio. Which of these effects dominates is unclear.

There are a number of reasons to suspect that child support performance would not increase after CSPIA. These include a decline in the intrinsic (Deci, 1971; Deci, Koestner, & Ryan, 1999) or public service (Perry & Wise, 1990) motivations of state officials after more child support goals were financially remunerated. Additionally, CSPIA may not have an effect on child support outcomes because it is an exercise in performance measurement rather than performance management. Moynihan (2008), Sanger (2013), and Behn (2003), among many others, suggest that how organizations use performance information is inextricably linked to their outcomes. For instance, the use of performance leadership teams and regular performance accountability meetings is an important practice advocated by proponents of CompStat- and CitiStat-like performance management systems (Behn, 2014; Smith & Bratton, 2001). A case study of CitiStat systems found that they varied in a number of important ways, such as the type of staff in charge of the program, the data used, and the structure of leadership meetings (Behn, 2006). Moreover, a recent meta-analysis found that practices such as performance benchmarking were positively associated with performance (Gerrish, 2016). In other words, organizations may claim to be managing performance, but if the extent of their efforts is publishing key performance indicators on a website, we ought to be dubious about claims to performance improvements.

Unfortunately, there is little systematic information about how all 50 states and local governments managed child support performance information over the time period examined in this analysis. However, there is substantial anecdotal evidence surrounding child support performance rewards both before and after CSPIA to suggest that they were highly salient and were the focus of significant bureaucratic attention (Doar, Smith, & Dinan, 2013; Gardiner et al., 2003; Solomon-Fears, 2013). While the examples given above suggest that some states and localities were using some elements of performance management routines, it of course does not suggest all units were using performance information or using performance information effectively. Thus, the possible finding of a null result in this paper does not suggest that performance management is ineffective, simply that the particular system examined here may have been deficient and should be balanced against the broader literature in this area.

In addition to the expectation of positive impacts on the new performance measures, there is the potential for CSPIA to induce dysfunctional behaviors. Performance management systems are well known to create such unintended consequences, typically described as perverse, strategic, or gaming behaviors (Courty & Marschke, 2003, 2004, 2008; Heckman, Heinrich, & Smith, 2002; Heinrich & Marschke, 2010).13 It is essential to search for these behaviors as they can adversely impact performance systems. If present, these strategic behaviors can offset performance gains or reveal that supposed performance gains are illusory. Based on the design and structure of performance incentives under CSPIA, three potential strategic behaviors seem particularly applicable here. First is the pure manipulation of data on child support outcomes by states, driven by the high-powered financial incentives. Second is the timing of reporting to maximize incentives payments (or avoid penalties) in a given year. Third is multitasking behavior in which states focus on the rewarded performance measures to the detriment of goals not rewarded.

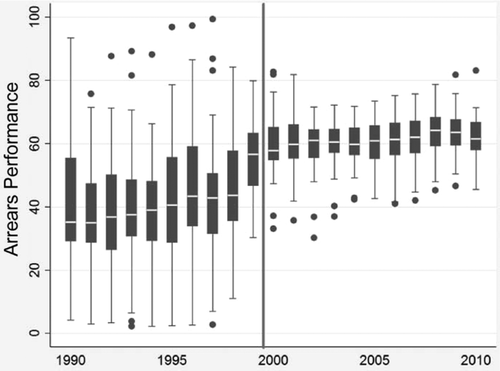

Pure data manipulation would have a dramatic effect on reported performance and on this analysis. Data manipulation is also not uncommon in performance systems; Heinrich (2007) cites a number of examples in policy fields ranging from education to health care. Although audits were performed at least once every three years prior to CSPIA, they were focused on administrative procedures rather than on the calculation of the cost-effectiveness performance measure. After CSPIA, every jurisdiction is audited for data reliability each year. The audit is conducted by identifying the universe of child support cases, from which 150 or more are selected for a data reliability audit. If a jurisdiction does not pass the data reliability audit, the state can receive zero payments for that measure and are subject to additional federal financial penalties (or receive a warning and have a corrective year). Given the severe financial penalties for lack of reliable data after CSPIA, it seems unlikely that data were manipulated, even though some states did fail audits after CSPIA.14 Prior to CSPIA there was no incentive to manipulate the child support outcomes that were later measured under CSPIA. There was so little incentive, in fact, that a few states appear to have incorrectly reported some measures in some years by making mathematical errors. States might have had an incentive to manipulate cost-effectiveness (either through collections or administrative expenditures). If this were the case, one might expect to see a discontinuity, either in the mean, median, or in the number of outliers when examining state cost-effectiveness ratios, but no such discontinuity appears in the data (box-and-whisker plots available upon request).

It is also possible that states delayed reporting of child support outcomes to maximize performance rewards. In this vein, Courty and Marschke (2004) examine the timing of graduation in the Job Training and Partnership Act, finding that managers delayed the timing of graduates. However, unlike the gaming behavior found in Courty and Marschke, delaying the reporting of child support outcomes to the next fiscal year does not appear to be a salient problem. In the case examined by Courty and Marschke, performance rewards were all-or-nothing at the cutoff. As mentioned previously, hypothetical performance payments are scaled between the 80 and 50 percent performance ceilings and floors. States above the 80 percent cutoff (states achieving at least 80 percent performance and thus obtaining 100 percent of their hypothetical performance payment) could increase performance in the next year if they delay reporting. However, once states are above 80 percent reliably year to year, delaying reporting provides no benefit. If states are delaying the timing of child support reporting, one might expect performance rewards to bunch just above the cutoffs. This does not appear to be the case. Of the 2,550 state-year performance measure observations post-CSPIA, just 76 observations are within two percentage points above the 80 percent cutoff (3 percent of observations). For states around the 50 percent cutoff (if states achieve less than the 50 percent cutoff the applicable performance reward is 0 percent), delaying performance reporting until the next fiscal year might prevent the state from being severely penalized. However, just 20 observations are within two percentage points above the 50 percent cutoff (0.8 percent of observations).15 Last, histograms of state performance found in Figure 1 suggest no bunching around the ceilings and floors; timing of reporting is not a salient problem.

CSPIA Performance Measure Reporting, by State, 2001 to 2010.

Notes: N = 459 for each histogram. Vertical lines indicate performance floors and ceilings. Bin size is 2 percent for all panels except the cost-effectiveness ratio. It is 0.1 for cost-effectiveness ratio. Source: OCSE Annual Reports, 2001 to 2010.

Unlike data manipulation and timing, however, multitasking behavior may be a concern. Multitasking is derived from a principal-agent model in Holmstrom and Milgrom (1991) in which individuals expend effort on rewarded activities and ignore or otherwise slack on unrewarded activities (or two dimensions of the same activity, like volume and quality).16 In the simplest form of their model, the firm (the principal) rewards its employee (the agent) for just one of two outcomes either due to the principal's preference or perhaps because the second outcome is unobservable. Employees then choose which activities to devote effort toward.

Multitasking behaviors after CSPIA would likely originate from increased attention to the newly rewarded child support outcomes at the expense of other goals. For example, because all five performance measures can be increased by working cases that are entirely contained within the home state, there is likely a stronger incentive (and perhaps pressure) to work these cases. On the other hand, working interstate child support cases may only contribute to a small number of performance measures (e.g., current support and the numerator of cost-effectiveness). Thus, interstate cases may be more costly and may take staff effort away from other cases. As a result, I would expect interstate collections to decline as a result of the adoption of the new performance measures.

It is an open question whether CSPIA would have created additional multitasking responses beyond those that may have existed previously. On one hand, child support services, such as medical support orders, do not contribute to total collections (the numerator of the cost-effectiveness ratio) and so, in theory, would have been underproduced both before and after CSPIA. On the other hand, anecdotal evidence suggests that some states partially ignored the cost-effectiveness ratio to focus on the child support goals they deemed more vital (Doar, Smith, & Dinan, 2013). Therefore, explicitly rewarding four new performance measures may have crowded out other child support goals, such as those considered by the Incentive Funding Workgroup: medical support orders, collections sent to other states (interstate collections), welfare cost avoidance, payment processing performance, and customer satisfaction. Ex ante, I expect new multitasking behaviors to harm the child support outcomes that were considered for performance measures but rejected.

In summary, I hypothesize that the four performance measures added by CSPIA will increase after the policy's implementation, the impact of CSPIA on cost-effectiveness will be ambiguous, and the alternative child support outcomes will decline due to a multitasking response.

Previous Analyses of CSPIA

There are two previous studies of CSPIA. Gardiner et al. (2003) prepared a report for the OCSE, as required by CSPIA. The researchers evaluated the implementation of CSPIA using a mix of data analysis and stakeholder interviews. Their analysis, using data from 2000 to 2002, found that states continued to improve in child support outcomes, even after controlling for socioeconomic factors. In interviews, they found “near-universal” support for the new incentives system among state and local child support staff, with strong support for the new performance measures as measuring the core services of the child support system.

Huang and Edwards (2009) used 1999 as the pre-CSPIA control and regressed state CSPIA performance scores on an index of CSE “capacity” as the key independent variable.17 The CSE index is roughly equivalent to a continuous quasi-treatment variable, in which a higher score indicated a higher capacity for effective policy implementation. Huang and Edward's index used three dimensions: state child support legislation, expenditures on the enforcement, and implementation ability.18 They report that a one-unit increase in the CSE index was associated with a 0.39-unit increase in the child support performance index (both indexes were standardized; units are standard deviations).

Huang and Edwards also note that states improved child support performance in all five measures. The overall collection rate for all states improved by 29 percent between 1999 and 2004 (41 to 53 percent). Similarly, paternity increased by 25 percent, order establishment by 18 percent, arrearage collection by 8 percent, and cost-effectiveness by 13 percent. They conclude that their results provide “evidence that the improvements of state child support performance and enforcement were substantial over the 1999–2004 period” (Huang & Edwards, 2009, p. 248).

The analyses in Huang and Edwards (2009) and Gardiner et al. (2003) differ from this analysis in three key ways. First, neither previous analysis considers the unintended consequences or gaming behaviors that may have resulted from a change in the incentives structure. Second, Huang and Edwards employ a CSE index that accounts for states’ ability to implement CSPIA, creating a continuous quasi-treatment variable. In contrast, this analysis uses an interrupted time series design that recognizes that all states were treated beginning in the same year. Perhaps most important, data from Huang and Edwards begin in 1999, after the reporting changes embedded in CSPIA. Similarly, Gardiner et al. (2003) use only three years of data after CSPIA. Both analyses are unable to capture underlying trends in child support outcomes prior to the passage of CSPIA. In contrast, this article extends child support outcomes back to 1990, when possible, to capture these trends. This data collection is discussed in the following section.

DATA

The performance measures rewarded by the federal government are calculated at the caseload level, and, where possible, this is the universe of my data. However, due to changes in child support reporting after CSPIA, some performance measures cannot be calculated in the same way as states are rewarded for them (or at all). Whenever possible, caseload-level variables are constructed from OCSE annual reports. When that is not possible, I use data from the Current Population Survey's Child Support Supplement (CPS-CSS) if possible. CPS-CSS differs from OCSE because determining a “case” is more difficult (more on this below). Ultimately, I was able to construct three of the five performance measures: order establishment, current collections, and the cost-effectiveness ratio. I was also able to construct two of the five alternative child support goals: interstate collections and medical support orders. Measurement of the performance measures (and the child support outcomes not rewarded) is summarized in Table 1. More detail about data collection is included in the Appendix.19

| CSPIA performance measure | How measured by CSPIA | How measured by this article | Data source | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Paternity establishment | Paternities established in that year/children born out of wedlock | N/A | N/A | Numerators have measurement discontinuities beginning in 1999. No alternative data sources available. |

| Order establishment | Number of IV-D cases with support orders/number of IV-D cases | Number of survey respondents with support orders established in that year | CPS-CSS | |

| Current collections | Amount collected for current support in IV-D cases/amount owed for current support in IV-D cases | OCSE annual reports | ||

| Arrearage collection | Number of IV-D cases paying toward arrears/number of IV-D cases with arrears due | N/A | N/A | Measurement discontinuity before and after CSPIA revealed by box plot. No alternative data sources available. |

| Cost-effectiveness | OCSE annual reports | Paper's measure and the performance measure are not the same. However, the measures have a correlation coefficient of 0.9996 between 2001 and 2010. | ||

| Total collections | N/A | Collections/population | OCSE annual reports & census | Numerator of cost-effectiveness. |

| Administrative expenditures | N/A | Administrative expenditures/population | OCSE annual reports & census | Denominator of cost-effectiveness. |

| Outcomes considered but not rewarded | ||||

| Medical support ordered and provided | N/A | Percent of respondents who are eligible for child support & have an order that stipulates medical support & medical support was actually provided | CPS-CSS | |

| Interstate collections | N/A | State collections sent to another state/population | OCSE annual reports & Census | |

| Welfare expenditures avoided | N/A | N/A | N/A | Unable to construct due to welfare policy changes. |

| Payment processing performance | N/A | N/A | N/A | Unable to construct with available data. |

| Customer satisfaction | N/A | N/A | N/A | Unable to construct with available data. |

OCSE's annual reports appear to be the most accurate source of data when they are available. Prior to state reporting changes in CSPIA, Guyer, Miller, and Garfinkel (1996) warned against using some of the data contained in OCSE annual reports in some circumstances.20 Some of those concerns are salient to this analysis. First, Guyer, Miller, and Garfinkel (1996) noted that some measures are created by summing three nonmutually exclusive categories, causing double or triple counting. These variables (i.e., caseload and orders established) are not used in this analysis. Second, they warn that the measure of total collections from OCSE reports does not adjust for state population or caseload size. In this analysis, I adjust for population, when necessary. Third, Guyer, Miller, and Garfinkel warn that OCSE data cannot control for the ability of noncustodial parents to pay child support. Control variables used here (e.g., personal income, gross state product) try to capture this variability between states.21

Ultimately, Guyer, Miller, and Garfinkel (1996) recommend using the CPS-CSS for data on child support outcomes, arguing that CPS-CSS ought to be a more accurate source of data given the low correlation between their child support index and data from OCSE annual reports. However, this paper is able to test correlations between CPS-CSS and OCSE annual reports after double counting was eliminated and state data began being audited. OCSE annual reports are now presumably the more accurate source of data.

Unfortunately, the correlation between OCSE annual reports and CPS-CSS post-CSPIA remains weak. For example, state child support order establishment from OCSE annual reports and state-level aggregates of weighted biennial data from CPS-CSS are modestly correlated with an r of 0.42 between 2001 and 2010.22 This weak correlation casts doubt on the recommendation of Guyer, Miller, and Garfinkel to prefer CPS-CSS over OCSE annual reports, as CPS-CSS is self-reported and small samples within states can make state-level estimates imprecise. OCSE annual reports may be the more accurate source for child support data when they do not suffer from the problems described above. An overarching problem between OCSE and CPS-CSS is that the denominator (a case) is often different; states may measure cases by the child or by the mother-father pairing. From CPS-CSS, it is sometimes possible to measure by child, but often data only exist for the mother. CPS-CSS and OCSE may differ, at least in part, due to this effect.23

CSPIA Performance Measures

CSPIA performance measures reward states for the stepwise process of enforcing child support: paternity establishment, order establishment, and collection of current and past-due support, as well as cost-effectiveness (total collections divided by administrative expenditures). While none of these performance measures are in mechanical opposition to one another, there may be trade-offs between cost-effectiveness and some of the other measures, particularly if new initiatives come at a higher cost than their incremental increase in collections. Some measures, such as paternity establishment and arrears performance, demonstrated data discontinuities and were not used. More detailed information about these measures can be found in the data Appendix.24

Order Establishment

Order establishment is the second step in the CSE process after paternity establishment. CSPIA measures support order establishment performance using the number of cases with child support orders under the Social Security Act of 1975 Title IV Part D (Title IV-D) divided by the number of Title IV-D cases. Unfortunately, both the numerator and the denominator have a large data discontinuity between 1998 and 1999 attributable to reporting changes. As a result, I use a measure of child support orders from the CPS-CSS. Using CPS-CSS, order establishment is measured in this paper as the percentage of children who have a biological parent absent from the household who in turn has a formal child support order that requires payments.

It is important to note, however, that this performance measure is different from the statutory measure. The mean of the variable used in this paper (50 percent) is lower than reported rates (about 80 percent) because not all individuals with an absent biological parent seek a child support order and may not be in the child support caseload. It is just as likely that survey recall is imperfect; individuals may not know that they have a child support order or whether it was formalized through the child support system.

A combination of recall error and random error while aggregating to the state level, the measure of order establishment used in this paper has a correlation coefficient of 0.46 with order establishment from OCSE administrative records after CSPIA (when data audits were introduced and double counting eliminated). This is considered a moderate correlation using a common rule of thumb of correlation coefficients, and one would hope for a higher correlation between measures of the same underlying construct even if they were measured differently. As a result, this measure of order establishment should be considered at best a “noisy” measure for the purposes of measuring the performance of CSPIA. Yet, because OCSE did not retain a consistent measure of order establishment throughout this period, this is likely the best data source available.

Current Collections

After determining paternity and establishing an order, states and local governments then start collecting current child support. Current collections are measured by CSPIA as the current support collected in the fiscal year divided by the total amount owed (collected and uncollected) for current support in child support cases. This amount is measured similarly both before and after CSPIA in the OCSE annual reports and so could be gathered directly from annual reports. There were 26 cases prior to 1999 in which the amount collected was greater than the amount due, or was unusually high given collections in previous years. These likely occurred due to mathematical reporting errors. These values have been changed to “missing.”25

Cost-effectiveness

The cost-effectiveness ratio is defined as the total Title IV-D dollars collected divided by total Title IV-D dollars expended.26 This is the only performance goal that existed before and after CSPIA. However, CSPIA changed how cost-effectiveness is measured by adding collections sent to other states to the numerator in order to promote interstate cooperation. The FY2001 annual report notes that this change caused cost-effectiveness ratios to be 25 cents higher after CSPIA ($4.17 compared to $3.92; OCSE, 2001). As indicated by this small increase in the cost-effectiveness ratio, interstate collections are only a small portion of total collections—5 to 6 percent of total collections during this period. Thus, changes in in-state collections largely overwhelm changes in interstate collections.

Total collections and administrative expenditures represent the numerator and denominator of the cost-effectiveness ratio and it is useful to examine them to separate the effect of CSPIA on the cost-effectiveness ratio. Therefore, I include real per capita total collections and real per capita administrative expenditures as dependent variables. OCSE annual reports measure total administrative expenditures, total collections, and collections sent to other states, and each is measured consistently for the period 1990 through 2010. To ensure that population is a suitable proxy for the child support caseload, I examined the correlation between state population and the child support caseload after CSPIA. I find that the correlation coefficient between state population and the size of the child support caseload is 0.94,27 suggesting that state population is an excellent proxy for the size of the child support caseload.

Child Support Outcomes Considered but Rejected

As mentioned above, the Incentives Fund Work Group considered five other child support outcomes for rewards but ultimately rejected them (Solomon-Fears, 2013). These alternative goals include medical support orders, interstate collections, welfare cost avoidance, payment processing performance, and customer satisfaction. This analysis was able to construct measures for medical support orders and interstate collections. The others were either never formally measured or not consistently reported by OCSE before and after the policy change. They also cannot be reconstructed from CPS-CSS. More detail can be found in the Appendix. As mentioned above, the decline in these alternative child support goals is suggestive of a multitasking response to explicit performance rewards.

Medical Support Orders

A medical support order stipulates whether a child support order contains a provision detailing which parent is responsible for the provision of medical care and health insurance and whether it was actually provided. CSPIA mandated that HHS and OCSE form a working group to identify the impediments to enforcement of medical child support (Ross, 1999). The group recommended that a medical child support performance goal be added as a sixth performance measure by FY2001. However, for unknown reasons, a medical support performance measure was never created (Solomon-Fears, 2013).

There does not appear to be a measure of “medical support” that is consistent in OCSE annual reports. The FY1998 OCSE Annual report, for instance, contains Table 42: “total number of support orders established that include health insurance” (OCSE, 1998). The FY1999 and 2000 annual report contains Table 24: Medical support. This includes a column labeled “Cases where health insurance is ordered” (OCSE, 2000). However, the magnitude of the two measures is very different. California, for instance, reports the medical support orders established as 175,227 in 1998 and 962,691 in 1999. No other comparable estimates can be found in OCSE annual reports before 1998.

| Order establishment | Current support | Cost-effectiveness | Total collections | Expenditures | Interstate collections | Medical support | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| State-specific quadratic (baseline) | −1.960 | 1.099 | 0.435* | 0.366 | −1.538* | −0.752** | 0.873 |

| (2.160) | (1.187) | (0.209) | (0.944) | (0.638) | (0.230) | (1.182) | |

| National linear trend | −1.764 | 0.952 | 0.407* | 0.529 | −2.197** | −0.651* | 1.074 |

| (1.824) | (1.313) | (0.174) | (1.307) | (0.664) | (0.299) | (0.974) | |

| State-specific linear trend | −2.054 | 1.489 | 0.408* | 0.353 | −1.417* | −0.676** | 1.307 |

| (1.978) | (1.183) | (0.193) | (1.183) | (0.625) | (0.221) | (1.139) | |

| National quadratic trend | −2.023 | 1.124 | 0.369* | 1.251 | −1.499** | −0.480 | 0.727 |

| (2.069) | (1.206) | (0.175) | (1.116) | (0.538) | (0.276) | (1.066) | |

| N | 867 | 1,038 | 1,071 | 1,071 | 1,071 | 1,071 | 867 |

| G | 51 | 51 | 51 | 51 | 51 | 51 | 51 |

- Notes. Standard errors clustered by state in parentheses. Only the post implementation coefficient is reported. Columns 1 and 2 contain the new CSPIA performance measures; columns 3 through 5 contain cost-effectiveness and its components; columns 6 and 7 are alternate child support outcomes (unrewarded). More detailed variable descriptions can be found in the article.

- *p < 0.05; **p < 0.01; ***p < 0.001.

As a consequence, medical support order establishment rates are collected from the CPS-CSS that ask whether the medical support, as mandated by the child support order, was actually provided. This measure mimics the medical support measure that states began reporting to the federal government in 2007. However, this measure contains the same problem of defining a “case” that applies to child support orders.28

Interstate Collections

Interstate cooperation among states has been a long-running priority of the federal OCSE. Although CSPIA did not contain a provision related to interstate child support collections, CSPIA did allow states to count collections sent to other states as part of their own collections for both current collections and cost-effectiveness performance measures. This created permissible double counting of child support collections in order to foster interstate cooperation. Collections sent to other states are dwarfed by in-state collections, as interstate collections comprise only 5 to 6 percent of all collections.

Interstate collections are measured in OCSE annual reports using the same method before and after CSPIA. In an important proof of this point, the OCSE annual report for FY1999 and FY2000 gives the amount of collections made on behalf of other states for five fiscal years. Values are consistent with (pre-CSPIA) FY1998 and FY1997 annual reports and there is no discontinuity or “jump” in the value of interstate collections. Interstate collections are measured in real per capita dollars for this analysis.

Control Variables

Control variables are included in regression models for three main reasons: first, to control for the size of the child support caseload; second, to control for the ability of noncustodial parents to pay child support; and third, to control for important changes concurrent with welfare reform.

The percentage of total births out of wedlock was collected from the National Center for Health Statistics and controls for the potential size of the child support caseload and child support administrative burden. This variable is likely to be positively associated with collections per capita (a larger base for collections) but potentially negatively associated with current collections for the same reason.

Two variables control for the likelihood both to pay and to seek orders—the poverty rate, collected from the U.S. Census Bureau Current Population Survey, and the state unemployment rate collected from the Bureau of Labor Statistics (BLS). Per capita personal income captures positive (or negative) changes in disposable income at the state level and is collected from the Bureau of Economic Analysis (BEA). It is adjusted to constant 2000 dollars using the consumer price index. These three variables should help to explain variation in collection amounts between states as well as during particular economic conditions (the late 1990s vs. the late 2000s, for example).

Finally, this paper employs three controls for changes in welfare policy and the welfare caseload. These controls are important because PRWORA had both direct and indirect impacts on the child supports system. Directly, PRWORA contained language that changed federal matching funds for paternity establishment and a requirement that states create a statewide automated data processing and information retrieval system by October 1997. The size of welfare caseloads indirectly impacts child support through two mechanisms. First, work requirements and lifetime limits may have induced some custodial parents to seek orders rather than cash assistance (the cost of seeking child support now being less than seeking cash assistance), which would positively impact both cases and collections. Second, PRWORA would have also had a negative impact on individuals who were induced to cooperate with state officials to receive assistance. This indirect effect is likely to be small because this requirement also exists in many states for other social programs, including Medicaid, state child health insurance, food stamps, and child care (Roberts, 2005).

Three variables are used to control for changes in welfare and welfare caseloads. First, a variable captures the month and year states fully implemented TANF (Crouse, 1999). This variable is measured as the percentage of the year in which states implemented TANF. Second, two variables capture the size and changes in the welfare caseload as reported by the Health and Human Services Administration for Children and Families (HHS ACF). HHS ACF reports on the size of the Aid to Families with Dependent Children (AFDC) caseload (Administration for Children and Families, 1998) and the size of the TANF caseload (Administration for Children and Families, 2014). After 2000, states started operating their own programs separate from TANF for reasons related to TANF work requirements—the controls used here include Separate State Program participants. I transform these data into the second and third variables. One is the average monthly number of TANF recipients per 1,000 residents in each state to measure the absolute size of the welfare caseload. The other variable codes for the percentage change in the average monthly number of TANF recipients by state from the previous year. This second variable helps to control for the rapid changes that occur at the outset of welfare reform.

Many of these control variables are also used by related empirical work in this area, including Huang and Edwards (2009; discussed previously) and Tapogna et al. (2004). Tapogna et al. (2004) examined potential “regression-controls” to adjust state CSPIA performance measures for socioeconomic factors in a report prepared for OCSE. The logic is that the residual variation is more likely to be attributed to state efforts and might result in more equitable performance payments between states. Regression controls were never adopted by OCSE, but the report provides a useful list of covariates that have been shown to change with child support outcomes. Two variables included in Tapogna et al. (2004) but excluded here are state expenditures per case and full-time equivalent (FTE) employees per case. These covariates likely overcontrol; the policy effect of CSPIA would be interpreted as “holding expenditures and FTE employees constant,” which makes little sense as states and localities have control over both staffing levels and expenditures.

METHODS

I examine the effect of CSPIA on state child support performance using a panel interrupted time series approach. The interruption in the panel data is the implementation of CSPIA. I model the interruption with a dummy variable representing the postpolicy period. Additionally, I include a dummy that represents the three-year implementation period between 2000 and 2002. The implementation dummy controls for changes during the first three years without excluding the implementation period from the panel. The reference period for both dummy variables is the period prior to the implementation of CSPIA. The interpretation of the policy dummy variable is the average impact of CSPIA each year on the outcomes of interest between 2003 and 2010, holding other factors constant. This dummy ought to capture both an intercept change and the average effect of a slope change. Because it is difficult to know whether CSPIA created just a sharp intercept change in child support outcomes or a gradual change, this paper also models the change as a slope shift by interacting the postpolicy dummy with a linear time trend.

Since all states implemented the changes in CSPIA at the same time, there is no natural comparison group. Lacking a comparison group, understanding the counterfactual state child support performance is an important consideration in order to estimate the policy effect. However, rather than make an untested assumption about a linear versus quadratic trend in child support outcomes prior to CSPIA, this analysis instead models several trend controls on the empirical data prior to the implementation of CSPIA (1990 to 1999). Linear and quadratic trend controls are used as well as state-level linear and quadratic functions (interaction of state fixed effects with the trend functions). All models also contain the covariates listed previously. I use both Akaike Information Criterion (AIC) and Bayesian Information Criterion (BIC) to choose between competing time trend controls. Minimization of these information criteria indicates best fit, imposing a penalty for inclusion of marginally relevant variables. This approach attempts to strike a balance between including too few versus too many time trend controls. Using both AIC and BIC, the information criterion in four of seven child support dependent variables is minimized using state-specific quadratic trends and the other three by a national quadratic trend. For simplicity, I have defaulted to the use of the state-specific quadratic trend but report the results of all four trends in a robustness check (see Table 2), finding that the choice of trend-control is largely immaterial; a national linear trend sufficiently controls for the background trend in child support outcomes and results are interpreted similarly. AIC and BIC values can be found in Table 3.

|

Order establishment | Current support | Cost-effectiveness | Total collections | Expenditures | Interstate collections | Medical support |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Akaike Information Criterion | |||||||

| National linear trend | 2,668.09 | 3,904.65 | 1,074.80 | 3,249.43 | 2,463.90 | 1,496.31 | 2,258.41 |

| State linear trend | 2,669.79 | 3,903.44 | 1,073.99 | 3,247.61 | 2,462.19 | 1,492.66 | 2,256.55 |

| National quadratic trend | 2,497.55 | 3,859.06 | 1,008.16 | 3,181.54 | 2,213.19 | 1,247.13 | 2,071.66 |

| State quadratic trend | 2,495.55 | 3,861.0 | 1,005.59 | 3,182.23 | 2,204.73 | 1,249.11 | 2,065.1 |

| Bayesian Information Criterion | |||||||

| National linear trend | 2,700.18 | 3,938.82 | 1,109.43 | 3,284.066 | 2,498.54 | 1,530.945 | 2,290.51 |

| State-specific linear trend | 2,705.88 | 3,941.88 | 1,112.97 | 3,286.578 | 2,501.16 | 1,531.63 | 2,292.65 |

| National quadratic trend | 2,533.65 | 3,899.48 | 1,042.80 | 3,216.179 | 2,247.83 | 1,281.77 | 2,103.75 |

| State quadratic trend | 2,527.64 | 3,893.22 | 1,044.56 | 3,221.196 | 2,243.70 | 1,288.08 | 2,101.24 |

- Notes. Models include state fixed effects and control variables described in the paper. Minimum values (bold) indicate best fit. Columns 1 and 2 contain the new CSPIA performance measures; columns 3 through 5 contain cost-effectiveness and its components; columns 6 and 7 are alternate child support outcomes (unrewarded).

RESULTS

Descriptive Figures and Statistics

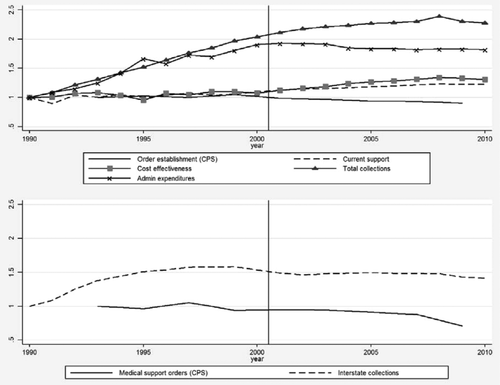

Descriptive statistics of the dependent variables and covariates can be found in Table 4. Figure 2 graphically illustrates national trends in child support outcomes. The top panel of Figure 2 contains rewarded goals (plus the components of the cost-effectiveness ratio), while the bottom panel shows trends in the goals considered but not rewarded. Every CSE outcome is rescaled to one in 1990 to provide a useful comparison among variables of different scales.29 The vertical line indicates 66 percent implementation of CSPIA.

| Mean | s.d. | Min | Max | N | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Dependent variables (notes, data source) | |||||

| Order establishment rate (0-100, CPS-CSS) | 50.09 | 9.92 | 17.47 | 80.67 | 867 |

| Proportion of current support collected (0-100, OCSE) | 55.27 | 11.34 | 3.69 | 91.92 | 1,038 |

| Cost-effectiveness ratio (OCSE) | 4.47 | 1.52 | 1.05 | 12.53 | 1,071 |

| Per capita total collections (2000$, OCSE) | 56.69 | 24.82 | 10.00 | 137.25 | 1,071 |

| Per capita administrative expenditures (2000$, OCSE) | 14.30 | 5.74 | 3.56 | 41.16 | 1,071 |

| Per capita interstate collections (2000$, OCSE) | 4.84 | 3.38 | 0.04 | 26.14 | 1,071 |

| Proportion of orders with medical support (CPS-CSS) | 18.23 | 5.33 | 0.00 | 36.39 | 867 |

| Covariates | |||||

| Proportion of births out of wedlock (0-100, NCHS) | 33.83 | 8.02 | 13.53 | 68.79 | 1,071 |

| Proportion of households in poverty (0-100, Census) | 12.70 | 3.64 | 4.50 | 26.40 | 1,071 |

| State unemployment rate (0-100, BLS) | 5.47 | 1.81 | 2.30 | 13.90 | 1,071 |

| Per capita personal income, in thousands (2000$, BEA) | 28.53 | 5.55 | 17.56 | 59.42 | 1,071 |

| TANF implementation (ACF) | 0.66 | 0.47 | 0.00 | 1.00 | 1,071 |

| Welfare recipients per 1,000 residents (ACF) | 26.30 | 19.57 | 0.50 | 132.24 | 1,071 |

| Percent change in state welfare recipients (ACF) | −0.84 | 26.56 | −82.24 | 106.52 | 1,071 |

- Notes. 2000$ indicates that dollar values have been adjusted to real 2000 dollars using CPI-U.

- OCSE, Office of Child Support Enforcement Annual Reports, 1990 to 2010; Census, Census's Population Estimates Program (black population) and Current Population Survey (poverty); CPS-CSS, Current Population Survey, Child Support Supplement from NBER (collected by researcher); NCHS, National Center for Health Statistics; BLS, Bureau of Labor Statistics; BEA, Bureau of Economic Analysis; ACF, Administration for Children and Families, a division of the Department of Health and Human Services.

Average National Child Support Outcomes, 1990 to 2010.

Notes: Variables scaled to 1 in 1990 (1993 for data from CPS-CSS). All dollar values adjusted to real dollars prior to rescaling. Vertical line indicates 66 percent CSPIA Implementation. Top panel contains measures rewarded by CSPIA (and the components of cost-effectiveness). The bottom panel contains child support outcomes not financially rewarded. Sources: OCSE Annual Reports 1990 to 2010, CPS-CSS, and U.S. Census (population).

Figure 2 speaks to the broader trends in CSE in the past two decades. As the figure suggests, significant improvements in national child support outcomes have occurred during this period. However, it also illustrates a significant “jump” in child support outcomes did not occur around the passage of CSPIA—total collections, for example, increase rapidly in the 1990s then increase at a slower rate in the post-CSPIA period. The large gains in the 1990s might be explained by two pieces of legislation in the 1980s—the Child Support Amendments of 1984 and the Family Support Act (FSA) of 1988. Both acts made a number of changes to child support processes that may have improved collections over this period. For example, one of the important provisions in both pieces of legislation relates to immediate income withholding. The 1984 law required that states enact delinquency-based income withholding. In other words, when noncustodial parents were sufficiently behind in payments, child support payment could be withheld from pay stubs much like federal income, social security, and Medicare. FSA changed the delinquency-based remedy to immediate withholding and made it presumptive unless an exception was made. One might imagine that this policy, and others like it, took time to wind through the sprawling child support caseload in the 1990s, before slowing as more child support cases had collections immediately withheld.30 Since about the year 2000, gains have been more modest, with an increase in total collections and a decline in collections sent to other states. These patterns are largely reflected in the quantitative analysis. Another trend to note is that administrative expenditures for CSE nearly doubled in the 1990s but then declined slightly through the 2000s. This may impact performance in other areas as state CSE programs attempt to do more with less.

Panel Interrupted Time Series

The results of the regression models for the seven child support outcomes are presented in Table 5. Every model uses a panel interrupted time series design with state fixed effects and state-specific quadratic trends. Results of the baseline specification are contained in Table 5. Table 5 is organized as follows: The leftmost two columns contain dependent variables for two of the four newly rewarded CSPIA performance measures. The middle three columns contain cost-effectiveness and its base components, total collections and administrative expenditures. The rightmost two columns are the goals that were considered but are not rewarded by CSPIA. The primary independent variable of interest is the top coefficient, post.

| Order establishment | Current support | Cost-effectiveness | Total collections | Expenditures | Interstate collections | Medical support | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Post CSPIA indicator | −1.960 | 1.099 | 0.435* | 0.366 | −1.538* | −0.752** | 0.873 |

| (2.160) | (1.187) | (0.209) | (0.944) | (0.638) | (0.230) | (1.182) | |

| Implementation period | −0.792 | 0.843 | 0.110 | 0.439 | −0.303 | −0.492** | 0.028 |

| (1.658) | (1.041) | (0.151) | (0.661) | (0.526) | (0.153) | (0.852) | |

| Percentage births out of wedlock | −0.202 | 0.020 | 0.058** | −0.118 | −0.206* | 0.061 | −0.087 |

| (0.569) | (0.361) | (0.018) | (0.158) | (0.078) | (0.082) | (0.179) | |

| Percentage households in poverty | 0.121 | 0.029 | 0.011 | −0.006 | −0.021 | 0.013 | 0.021 |

| (0.206) | (0.190) | (0.018) | (0.078) | (0.065) | (0.024) | (0.149) | |

| Unemployment rate | −0.819 | 0.386 | −0.048 | 0.189 | 0.174 | 0.055 | −0.280 |

| (0.564) | (0.415) | (0.048) | (0.186) | (0.179) | (0.046) | (0.332) | |

| Per capita personal income | −0.708 | 0.844 | −0.031 | 0.716*** | 0.122 | 0.166* | 0.113 |

| (0.618) | (0.449) | (0.059) | (0.159) | (0.167) | (0.064) | (0.395) | |

| TANF implementation | 1.481 | −0.292 | 0.321* | 1.260 | −1.134* | 0.252 | 0.173 |

| (2.034) | (2.129) | (0.149) | (0.647) | (0.525) | (0.346) | (1.284) | |

| Welfare recipients per 1,000 residents | 0.046 | 0.026 | 0.004 | −0.039 | −0.023 | 0.038 | 0.044 |

| (0.106) | (0.073) | (0.006) | (0.040) | (0.025) | (0.021) | (0.063) | |

| Percentage change in state welfare recipients | 0.001 | −0.001 | 0.000 | 0.018*** | 0.002 | −0.001 | −0.008 |

| (0.009) | (0.004) | (0.001) | (0.003) | (0.002) | (0.001) | (0.006) | |

| Constant | 74.900* | 21.618 | 3.177 | 11.389 | 9.578 | −4.791 | 17.551 |

| (30.437) | (16.757) | (1.722) | (6.818) | (5.171) | (4.231) | (14.810) | |

| N | 867 | 1,038 | 1,071 | 1,071 | 1,071 | 1,071 | 867 |

| N groups | 51 | 51 | 51 | 51 | 51 | 51 | 51 |

| R2 | 0.370 | 0.525 | 0.711 | 0.977 | 0.756 | 0.720 | 0.399 |

| Adj. R2 | 0.278 | 0.468 | 0.678 | 0.974 | 0.728 | 0.687 | 0.310 |

- Notes. Standard errors clustered by state in parentheses. State fixed effects and state-specific linear and quadratic trend coefficients suppressed. Columns 1 and 2 contain the new CSPIA performance measures; columns 3 through 5 contain cost-effectiveness and its components; columns 6 and 7 are alternate child support outcomes (unrewarded). More detailed variable descriptions can be found in the article.

- *p < 0.05; **p < 0.01; ***p < 0.001.

The effect of CSPIA on the two newly rewarded performance measures examined in this paper, order establishment and current support performance, have opposing signs but neither are statistically different from zero. Practically speaking, both effects are small as sample means are 50 and 55 percent, respectively. Recalling above, the interpretation of these coefficients is the average increase in child support in the post-CSPIA era. These small results (one positive, one negative but both indistinguishable from zero) suggest that state CSE agencies may have difficulty improving child support outcomes beyond the background trend. The hypothesis that CSPIA may improve the measured performance goals finds little support.

The rightmost columns indicate that one of the two child support outcomes considered but rejected by the Incentive Funding Workgroup declined in the post-CSPIA period. The other was not statistically different from zero. Interstate collections (collections sent to other states) declined by about 75 cents per capita, a meaningful decline (as mean per capita interstate collections are $4.76). This result is statistically significant at the 0.01 level. However, orders that stipulate (and provide) medical support were not statistically different from zero. The hypothesis that CSPIA may have induced a multitasking behavior finds support in the negative impact on interstate collections.

Cost-effectiveness also increased slightly in the baseline specification—44 cents more collected per dollar spent. This is a modest policy effect given a mean sample cost-effectiveness ratio of $4.84. Both a slight increase in total collections (36 cents per capita) and a significant decline in administrative expenditures ($1.54 per capita) drive this result. Among the trio both the effect of CSPIA on cost-effectiveness and administrative expenditures reject the null hypothesis test at the 5 percent level. Although the theoretical sign of cost-effectiveness was ambiguous, the results presented here suggest that state and local CSE agencies increased total collections for less expenditures after CSPIA, holding socioeconomic factors constant.

Using the literature above, I hypothesized two results. First, the intent of the system is that the newly rewarded performance measure would show positive results, although empirical evidence is mixed on whether performance systems actually deliver such results. Second, based on the gaming literature, the alternative measures might decline. I did not have a strong ex ante expectation about cost-effectiveness and its component parts because this performance measure continued from the previous incentives regime. While the child support outcomes increased unconditionally, conditional on other variables and the trend prior to CSPIA, the two new performance measures did not change substantially in the decade after CSPIA. These results suggest that CSPIA had little effect on child support outcomes, contrary to the findings of Huang and Edwards (2009) and the naïve examination presented at the outset of this paper.

Lack of positive results is fairly common in the research on performance management; the public performance management literature suggests that many performance systems do not improve organizational performance (Gerrish, 2016). As mentioned above, there are a number of reasons to explain this result. First, state organizations may not use performance information effectively or financial rewards reduce the intrinsic or public service motivation of state child support officials. Which of these hypotheses (among others) dominates cannot be reconciled with the available data. Additionally, state introspection on in-state cases has apparently hampered interstate cooperation, resulting in a decline in interstate collections. However, based on the evidence, CSPIA more than compensated for this decline with an increase in total collections, of which interstate collections comprise about 5 to 6 percent of total collection. Declines in interstate collections remind performance management researchers to examine potential unintended consequences in performance management systems—unwittingly or not, performance rewards may create situations in which individuals or organizations ignore ancillary goals. Because there are so many ways to game performance systems (cream-skimming, parking, timing of reporting, or the multitasking behavior found here), researchers should be aware of the variety of possible unintended consequences when evaluating performance systems.

Limitations

There are three main limitations to these results. First is the lack of a comparison group, without which it is difficult to assess counterfactual child support outcomes. For example, if state child support performance plateaued absent CSPIA, the post-CSPIA indicator would underestimate the true effect of the policy change. This would also be the case if policymakers implemented CSPIA against the backdrop of concerns about future performance declines. While controls for the time trend and other factors attempt to adjust for these unknown factors, the results are limited by the data.

The second limitation is that this analysis is unable to assess the effect of CSPIA on paternity establishment, arrearage collections, welfare cost avoidance, payment processing performance, and customer satisfaction, owing to a lack of consistent reporting of child support outcomes, painting an incomplete picture of how states responded to CSPIA. This problem could be rectified by OCSE maintaining consistent reporting of some child support outcomes after the policy change for at least a few years after any future reporting changes, as recommended in at least one performance measurement handbook (Hatry, 2006, for example).

A final limitation to these results is that they are a black-box approach to examining the effect of the performance management system. CSPIA mandates annual reporting of state performance but does not stipulate how (or whether) operational data are used on an intrayear basis to support performance routines (nor evaluate whether those routines are successful). Previous research describes the importance of distinguishing performance management from merely measurement; the latter would not be expected to improve organizational performance due to the lack of management routines (Moynihan, 2008). However, because this analysis lacks data on state-level management practices, it was not possible to examine how state and local governments used performance information. Anecdotal evidence suggests that the financial incentives did cause states to focus attention on the performance measures (Doar, Smith, & Dinan, 2013; Gardiner et al., 2003; Solomon-Fears, 2013), though perhaps only on a year-over-year basis.

ROBUSTNESS CHECKS

Earlier, I described the time trends that were examined against child support outcomes prior to CSPIA. Although AIC and BIC both indicated that a state quadratic trend best fit the preimplementation data, results from models using the other time trend controls are also reported in Table 2. Only the coefficient on the policy lever variable, post, is reported in Table 2. While these alternative time controls leave more variation in the dependent variable to be explained by the effect of CSPIA, it also may contain more contaminating variation incorrectly attributed to CSPIA—the alternative trends may not fully capture changes in child support outcomes prior to the policy.

Results from the alternative time trend specifications in Table 2 are quite stable. One exception is the coefficient on post for interstate collections, which is not statistically different from zero in one of the four models. However, the interpretation would be similar as the magnitude of the coefficient is similar. The magnitude and interpretation of all other coefficients are similar in size and statistical significance levels. These results strongly suggest that the choice of time trend specifications is not an important consideration for this analysis and results are not sensitive to this particular modeling choice.

In addition, Table 6 reports the same models as Table 2, using a postpolicy slope rather than an intercept shift. In these models, the postpolicy dummy is replaced by a dummy interacted with a linear time trend. Like Table 2, Table 6 reports only the slope for the four trend specifications. This specification both confirms and strengthens the findings in Table 5. For example, the coefficient for the postpolicy slope on interstate collections is estimated more efficiently than in the dummy specifications. The general pattern of statistical significance is similar between Tables 2 and 6; I find a multitasking response, some improvements in cost effectiveness, and no impact on newly rewarded performance measures. The interpretation of these models is a bit more fraught than the baseline; in a fixed effects framework all trend variables are demeaned. The interpretation is multiplicative by year after policy implementation (2003 to 2010; coded 1 to 9), controlling for other variables and the background trend.

| Order establishment | Current support | Cost-effectiveness | Total collections | Expenditures | Interstate collections | Medical support | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| State-specific quadratic (Baseline) | −0.162 | 0.097 | 0.035* | 0.015 | −0.126* | −0.061** | 0.064 |

| (0.164) | (0.094) | (0.017) | (0.076) | (0.051) | (0.019) | (0.089) | |

| National linear trend | −0.163 | 0.037 | 0.034* | −0.361** | −0.276*** | −0.076** | 0.053 |

| (0.158) | (0.128) | (0.013) | (0.121) | (0.055) | (0.027) | (0.082) | |

| State-specific linear trend | −0.163 | 0.077 | 0.040* | −0.303** | −0.230*** | −0.081*** | 0.066 |

| (0.160) | (0.113) | (0.015) | (0.112) | (0.053) | (0.020) | (0.090) | |

| National quadratic trend | −0.162 | 0.095 | 0.029 | 0.071 | −0.127** | −0.040 | 0.056 |

| (0.157) | (0.101) | (0.015) | (0.091) | (0.044) | (0.022) | (0.081) | |

| N | 867 | 1,038 | 1,071 | 1,071 | 1,071 | 1,071 | 867 |

| G | 51 | 51 | 51 | 51 | 51 | 51 | 51 |

- Notes. Standard errors clustered by state in parentheses. Only the post × linear trend coefficient is reported. Columns 1 and 2 contain the new CSPIA performance measures; columns 3 through 5 contain cost-effectiveness and its components; columns 6 and 7 are alternate child support outcomes (unrewarded). More detailed variable descriptions can be found in the article.

- *p < 0.05; **p < 0.01; ***p < 0.001.

DISCUSSION AND CONCLUSION

This paper set out to evaluate the comprehensive reform of the CSE incentives system in 1998. It examined child support outcomes using data from 1990 to 2010 from all 50 states and the District of Columbia using a panel interrupted time series design. Child support outcomes were divided into three groups: the newly rewarded child support outcomes, child support outcomes that were considered for performance rewards but rejected, and the retained performance measure, cost-effectiveness and its components.

Models found that CSPIA had little positive effect on child support outcomes. Neither of the two new performance measures evaluated here showed marked improvement. Moreover, an alternative child support outcome, interstate collections, decreased significantly. This suggests that states may have focused on rewarded child support outcomes to the exclusion of at least one unrewarded goal, a potential multitasking gaming response.

These results suggest that CSPIA may not be the unambiguous success reported by some of the academic literature (Huang & Edwards, 2009; Huang et al., 2008), nor perceived by practitioners (Gardiner et al., 2003; Solomon-Fears, 2013). The results presented here suggest that the policy itself had little to no effect on child support outcomes, and observed improvements may have been continuations of trends in the late 1990s.