Testing the School-to-Prison Pipeline

Abstract

The School-to-Prison Pipeline is a social phenomenon where students become formally involved with the criminal justice system as a result of school policies that use law enforcement, rather than discipline, to address behavioral problems. A potentially important part of the School-to-Prison Pipeline is the use of sworn School Resource Officers (SROs), but there is little research on the causal effect of hiring these officers on school crime or arrests. Using credibly exogenous variation in the use of SROs generated by federal hiring grants specifically to place law enforcement in schools, I find evidence that law enforcement agencies learn about more crimes in schools upon receipt of a grant, and are more likely to make arrests for those crimes. This primarily affects children under the age of 15. However, I also find evidence that SROs increase school safety, and help law enforcement agencies make arrests for drug crimes occurring on and off school grounds.

INTRODUCTION

The relationship between educational institutions and the criminal justice system is complex. Localities that have both high-quality educational infrastructure and a well-functioning criminal justice system can be places where children in low-income families can easily overcome barriers to opportunity. Education is one of the strongest predictors of lifetime wealth, and lack of access to quality education is one of the most frequently cited constraints on upward mobility in areas of persistent poverty (Autor, Katz, & Kearney, 2008; Bailey & Dynarski, 2011). Areas of concentrated poverty are also typically characterized by high rates of crime and disorder, which can have adverse effects on the educational attainment and future job prospects of young people growing up in those neighborhoods (Katz & Turner, 2008; Ludwig et al., 2013; Sharkey et al., 2014).1

Inside school walls, bullying and aggressive behavior can have long-lasting psychological effects on victims, and meta-analyses of antibullying and antiviolence programs find that certain policy levers can improve school safety (Ttofi & Farrington, 2010; Wilson & Lipsey, 2007). One particular type of antiviolence policy that became increasingly common in the 1990s is for school districts to partner with local law enforcement agencies to have specially trained police officers stationed inside schools.2 These SROs serve two purposes: to maintain order and safety for the students and teachers in a way that a typical school security guard could not, and to positively interact with students on a daily basis, normalizing officers in the eyes of students and potentially improving police and community relations more broadly (Ray, 2013).

At the same time that a proactive criminal justice agency can complement strong educational infrastructure in communities, criminal justice agents that are too aggressive in the arrest, prosecution, and sentencing of people who violate the law can reduce the private return to investment in education. Children who are arrested and incarcerated are less likely to complete high school (Hjalmarsson, 2008), and certain types of criminal records limit a potential student's eligibility for federal grants and loans that reduce the cost of a college degree (Lovenheim & Owens, 2014). Consistent with this, people who become involved with the criminal justice system, particularly at a young age, are more likely to continue to be criminally involved (Aizer & Doyle, 2015), and suffer from persistent negative employment consequences of that criminal record (Pager, 2003; Western, 2006).

The use of sworn officers within schools has recently been subject to increased scrutiny as a cause of what has become known as the “School-to-Prison Pipeline” (Wald & Losen, 2003). Since SROs are sworn law enforcement officials with arrest powers, critics contend that SROs may be more likely to respond to student misbehavior by making an arrest, which security guards or principals are not able to do (American Civil Liberties Union, 2014a, 2014b). If SROs make arrests in cases where a principal would otherwise use confidential, in-school, discipline, this lowered threshold at which misbehavior becomes criminal behavior can lead to otherwise similar students in different schools accumulating different criminal records. While few juvenile arrests directly result in incarceration, this is a key entry point into the School-to-Prison Pipeline; becoming “known to police” may increase the severity of the criminal justice system response to future deviant behavior (e.g., Brunson, 2007; Herbert, 2010,). In addition, analysis of nationally representative youth surveys suggests that simply being stopped by police is associated with reduced use of banks and hospitals as well as lower employment rates (Brayne, 2014). Finally, to the extent that schools with SROs are more likely to be located in cities and areas with larger minority populations, hiring these officers can exacerbate racial disparities in the criminal justice system.3

While there is a large literature on the impacts of crime and criminal justice on youth outcomes that is relevant to the potential costs of benefits of SROs, there is much less direct evidence on the causal impacts of the program itself. A handful of project evaluations have found that SROs have increased perceptions of school safety (Raymond, 2010). A federally funded evaluation of SROs (Finn & McDevitt, 2005) primarily focused on what SROs do, and noted that “most programs fail to collect important process and outcome evaluation data” (Finn & McDevitt, 2005, p. 4). Recent survey evidence has found that schools with SROs have 12 percent higher official crime rates, particularly for more marginal offences such as weapons and drug violations, which went up by almost 30 percent after SROs were hired (Na & Gottfredson, 2013). Na and Gottfredson do not measure arrests directly, but they also find large increases in the probability that less serious crimes were reported to the police.

Of course, the finding that schools with SROs have higher official crime rates, or even that students in SRO schools are more likely to be arrested, is not necessarily evidence that SROs enhance the School-to-Prison Pipeline. Indeed, if SROs are viewed as solutions to a school safety or school crime problem, then the observation that there are more crimes or arrests occurring where SROs are hired is simply a correlation generated by reverse causality and omitted variable bias (underlying school safety). The size of this bias is likely substantial; failure to address the endogenous (and noisy) relationship between police employment and crime prior to the 2000s resulted in a number of papers that found either null or positive effects of police on crime rates, and a later literature that carefully addressed these empirical issues has consistently found that the presence of more police officers reduces overall crime (Nagin, 2013).

In this article, I present the first evidence on the relationship between SROs and the School-to-Prison Pipeline that uses a credible source of quasi-experimental variation in the presence of law enforcement officers in schools. Specifically, I exploit variation in the timing and size of federal grants distributed by the Department of Justice's Community Oriented Policing Services’ (COPS) “Cops in Schools” (CIS) program, which allowed law enforcement agencies to staff SRO positions, to identify the impact of these SROs on school safety, the rate of officially recorded crimes in and out of schools, and with the arrest rates of teenagers and young children for offenses that occur in and out of the classroom.

I first demonstrate that CIS grants were awarded to police agencies and local governments that initially had higher crime rates in and out of school, suggesting that previous studies that do not take endogenous determination of SROs and crime into account could produce biased estimates of the impact of those officers in schools. I then show that, conditional on agency fixed effects and demographic control variables, agencies that did, and did not, receive CIS grants had statistically identical trends in both in- and out-of-school crime as well as arrest rates for crimes occurring in school. This is consistent with previous research on COPS hiring grants, which found that grant size was primarily determined by level differences in crime and employment across cities, but was conditionally orthogonal to preexisting trends in crime and police employment (Evans & Owens, 2007).

I then use three records of police officer employment and school security to examine the impact of CIS grants on law enforcement. I show that unlike other COPS grants, CIS grants had an immediate, although heterogeneous, impact on overall law enforcement employment, as reported in the Uniform Crime Reports. Using a sample of law enforcement agencies in the Law Enforcement Management and Administrative Statistics (LEMAS), I then show that CIS grants were specifically used to staff SRO positions, and that one additional CIS officer granted essentially doubled the number of SROs an agency employed within one month of grant receipt. Finally, I show that schools located in counties where local law enforcement agencies received CIS grants were more likely to report having armed security staff, as reported in the National Center for Education Statistics School Survey on Crime and Safety (SSOCS) in 2003, 2005, and 2007.

I next use the receipt of CIS grants to estimate the causal reduced-form relationship between these grants and the School-to-Prison Pipeline. I begin by exploring the impact of CIS grants on school safety in the SSOCS. Based on these surveys of school administrators, I conclude that CIS grants were associated with reductions in school crime rates. At the same time, however, I find small, but imprecisely estimated, increases in the likelihood that school administrators report contacting police about the incidents that do still occur.

I more rigorously estimate the impact of SROs on crimes known to police and arrests using the National Incident Based Reporting System (NIBRS) between 1997 and 2007. The NIBRS allows me not only to differentiate between officially reported crimes based on location, but also to identify the number of arrests made as a result of these reported crimes and the age of the person arrested. I find that, conditional on a rich set of school characteristics, police jurisdictions that received CIS grants did learn about more violent crime taking place in schools, along with more weapons and drug violations. However, the agencies also learned about more minor violations that occurred outside of school, particularly drug offenses. Taken at face value, this suggests that hiring SROs may have increased the propensity of citizens to contact the police in general.

In addition, I find that law enforcement agencies that were awarded CIS grants were more likely to make arrests for crimes committed in school, and this is driven by the arrest of juveniles who are less than 15 years old. I do not find evidence that, on average, hiring SROs results in more arrests for crimes committed off school grounds, with the exception of arrests for drug charges. Dividing the SSOCS and NIBRS sample by the area's nonwhite population fails to yield evidence that CIS officers exacerbated the School-to-Prison Pipeline in minority districts, although data coverage in the NIBRS limits my ability to generalize to schools in large urban areas.

Taken as a whole, these results suggest that there are potentially important negative consequences to posting law enforcement officials in schools, but also some potential benefits. A well-intentioned grant program aimed at improving school safety for at-risk children appears to have also resulted in the accumulation of arrest records for young students. At the same time, there is evidence that people were more likely to contact police about drug crimes occurring outside of schools, suggesting that posting law enforcement officers in schools may help to improve police-community relations more broadly. Finally, perhaps more importantly, and in contrast with existing research, I find evidence that hiring SROs increases school safety.

COPS IN SCHOOLS AND THE VCCA 1994

In the early 1990s, crime rates in the United States were at historically high levels. In order to better motivate state and local governments to invest in criminal justice infrastructure, in September 1994, Congress enacted the Violent Crime Control and Law Enforcement Act (VCCA 1994). The VCCA 1994 expanded the scope of federal law enforcement authority on a number of dimensions, including banning the sale of assault weapons, expanding the list of federal capital offenses, formalizing the criminality of domestic violence, and prohibiting incarcerated people from applying for Stafford and Pell grants. The VCCA 1994 also authorized over $18 billion in new federal expenditure, almost all of which was to be allocated to state and local governments that invested in particular types of criminal justice policies. A new office in the Department of Justice, the COPS office, was created by the VCCA 1994 specifically for the purpose of distributing roughly $7.5 billion in grants to local policing agencies that subsidized the cost of hiring policing officers, investing in technology, or developing specialized policing strategies. To date, the COPS office has distributed over $14 billion to local law enforcement agencies.4

One of the specialized policing strategies incentivized by the COPS office was the CIS program. CIS grant funds were intended to supplement the salary of an officer who would work in a primary or secondary school as an SRO. The first round of CIS funding was awarded in 1999, just as funding for the broader Universal Hiring Program (UHP) was beginning to decline.5 CIS grants were awarded through 2005, and in those seven years just over $750 million was granted to local law enforcement agencies.6

CIS grants, which lasted for three years, could only be used to create new SRO positions, unlike UHP grants that could be used to hire new officers more generally. While this restriction in use may have made CIS grants less desirable to law enforcement agencies than UHP grants, CIS grants were larger—initially capped at $100,000 per officer and later raised to $125,000 per officer, compared with a $75,000 cap for UHP. CIS grants also did not technically require that a new officer be hired by the department, only that a new SRO position be created and the CIS funding be used to pay that SRO's salary—an existing officer could be reassigned from their regular beat to an SRO position.

Once hired, SROs have a number of responsibilities, which vary from school to school. As sworn officers, all SROs have the authority to make arrests and issue citations, sometimes independently of the principal, and serve as a liaison between the school and local criminal justice authorities. If the existence of police inside of a school lowers the cost to school employees of notifying law enforcement about student misbehavior, the behavioral threshold at which a school administrator will choose to call the police in order to discipline students will fall, and police will become involved in school discipline more frequently. The specific idea that SROs have “criminalized” behavior that would previously have been informally dealt with by school administrators is the School-to-Prison Pipeline.

At the same time, an important component of the SRO idea, as laid out in the Omnibus Crime Control Act of 1968, is to normalize police officers to students who might not typically interact with law enforcement officials, and to promote trust between young people and the officers who serve them in their community. Consistent with this official goal, SROs frequently serve a number of nondisciplinary functions, including teaching classes, developing emergency response plans, and working with students and faculty to develop ideas to improve school safety.

If SROs are seen as a positive part of the school community, and develop trusting relationships with students, SROs may be associated with higher arrest rates, but not because misbehavior is being criminalized. If students (and teachers) who are exposed to SROs view police officers as friendly, helpful people who are interested in protecting rather than persecuting them, students may become more likely to notify SROs (or police in general) when they observe a crime. Schools can be dangerous places for young people; violent crimes by young people tend to increase when school is in session (Jacob & Lefgren, 2003), and students between 12 and 18 years old experience more victimizations in school than out of school (Robers et al., 2014). At the same time, roughly 63 percent of crimes occurring in schools are not reported to law enforcement by school officials; underreporting is even higher for violent crimes, where 74 percent are unrecorded by police. This difference in reporting is due primarily to low reporting of fights where no weapons are involved and high reporting of drug offenses (Robers et al., 2014). Overall, in 2012 young people between the ages of 12 and 17 reported roughly 16 percent of their own violent victimizations to police, one-third the rate in the general population.7 To the extent that some fraction of those involved in unreported incidents should have been referred to the justice system, increasing reporting rates can protect victims and lower crime in the long run. Indeed, a handful of small surveys about student perceptions of SROs tend to find that students, particularly non-delinquent students, generally view SROs favorably, especially relative to police officers they encounter outside school (Brown & Benedict, 2005; Hopkins, 1994; Jackson, 2002).

Critically for my analysis, positive relationships between SROs and students would reduce any stigma cost of reporting, but unlike the School-to-Prison Pipeline, this should increase the reporting of all crime, not just crimes that occur in schools. Comparing the rates at which police officers learn about crimes occurring in and out of schools can therefore be used to differentiate between improved community relationships, which would tend to increase all reporting, and simple relabeling of misbehavior, which would increase reporting in schools only.

DATA

The central component of the data used in this analysis is grant-level data on all awards made by the COPS office between 1994 and 2007. Between 1999 and 2004, a total of 6,631 SRO positions were funded by the COPS office through over 3,000 three-year grants; this is much smaller than the UHP program, which funded over 67,000 officers though 2004.

Using the law enforcement identifiers (ORIs) of grant recipients, I merge this information with data on police employment records from three sources. The Uniform Crime Reports Law Enforcement Officers Killed and Assaulted (LEOKA) reports the number of sworn officers employed as of October 1 in each year between 1997 and 2007. While there is no information on what the officers do, these data are annual, and cover close to the universe of all law enforcement agencies. Specific information on SRO employment is recorded in the Law Enforcement Management and Administrative Statistics (LEMAS). LEMAS data record operating statistics for a random sample of law enforcement agencies in the United States, and in 1997, 1999, 2000, 2003, and 2007, agencies were asked how many SROs they employed in June (2003 and earlier) or September (in 2007). In these five LEMAS waves, I was able to positively identify the number of COPS grants awarded to 3,960 agencies who served between 5,000 and 100,000 people, 2,340 of which were in the survey more than once.

Using the county where the CIS recipient is located, I then linked the COPS data to the 2003 to 2004, 2005 to 2006, or 2007 to 2008 waves of the SSOCS, which allows me to examine the impact of CIS grants on the probability that local schools hire security guards. Unlike in the LEOKA or LEMAS, CIS grants in this case will generate what is essentially an intent-to-treat effect—I estimate the maximum number of CIS grants per 10,000 county residents that could have been directed toward a school in the SSOCS by calculating the total number of active CIS grants in a given month in a given county, and taking the average monthly value during the months that school was in session. Roughly one-fourth of the schools in the SSOCS are located in counties that received CIS grants, which were roughly 0.18 officers per 10,000 county residents on average. Like the LEMAS, each wave of the SSOCS is a nationally representative sample of just over 2,500 of primary and secondary schools, and only a small fraction of schools (fewer than 200) are surveyed more than once, meaning the assumptions required to draw causal statements about CIS grants are stronger than those using longitudinal data.

With this important limitation in mind, the SSOCS data form my first source of data on how SROs affect the school environment and school administrators, typically principals, are asked to report the number of behavioral incidents that occurred in the most recent school year. I aggregate these behaviors into four categories: violent crimes (rape, sexual battery, robbery, assault, and threats), property offenses (theft and vandalism), drug offenses (drugs or alcohol found on students), or weapons charges (guns or knives). The SSOCS also asks school administers about incidents that were “reported to police or other law enforcement.” The survey instrument does not clarify whether or not notifying the SRO (or other sworn officer who works in the school) about an incident qualifies it as “reported to law enforcement,” or if “reported to law enforcement” means that the administrator herself contacted external local law enforcement by, for example, calling 9-1-1. However, comparing the change in crimes the school administrator considers reported to the police relative to the crime rate that she is aware of can provide some complementary evidence about the change in formalization of discipline in schools that hire more security guards.

I more precisely measure crimes reported to police and arrests made using the NIBRS between 1997 and 2007. The NIBRS data are collected annually by the FBI, and can be thought of as a more detailed version of the Uniform Crime Reports (UCR).8 In large part because of the enhanced data collection requirements of the NIBRS, only a small fraction of law enforcement agencies participate. Roughly 17,000 law enforcement agencies report crime and arrest data to the UCR, but just over 4,900 agencies reported data to the NIBRS in 2007, and just under 2,000 participated in 1997. NIBRS agencies tend to be small; none of the 15 largest cities in the United States are represented in the NIBRS. For each of the 4,084 police departments in the NIBRS that served between 5,000 and 100,000 people, I identified how many active COPS grants that agency was handling in each month between 1997 and 2007.9 A total of 759 CIS officers (out of 6,631 granted) were directly awarded to an NIBRS agency, which is roughly proportional to the overall NIBRS participation rate by law enforcement agencies.

For all criminal acts associated with each criminal incident recorded in the NIBRS, I identified whether or not the crime took place in a school or college and what type of crime it was (violent, property, a drug offense, or a weapon law violation). I then further divided those crimes by characteristics of the people arrested in association with that criminal incident, if any arrest was made. Arrestees under the age of 15 are classified as “minors,” and arrestees between 15 and 19 as “young adults.” I then created a monthly data set that recorded the total number of criminal acts that police knew about, by whether or not the crime took place in school or out of school, along with the total number of individual arrests made by the police, based on whether or not the underlying crime took place in or out of school, and the age of the person arrested.

I supplement my criminal justice data with two sets of variables that are plausible correlated both with local crime and with the propensity of the school to hire, or apply for, a CIS grant. County-level measures of school resources are drawn from the National Center for Education Statistics Common Core of Data, and include the school district revenue per resident between the ages of 5 and 19, the number of county residents between the ages of 5 and 19 per school, the number of high school graduates per county resident between the ages of 15 and 19, and the number of students per teacher. These variables are updated in September of each year. In addition, annual information on county-level demographic information is drawn from Census Bureau intercensal and small area income and poverty estimates, specifically the overall and child poverty rate, the log of real median household income, the percentage of county residents who are nonwhite, and the percentage of children between the ages of 15 and 19 who are nonwhite.

Tables 1 and 2 summarize some basic facts about crime, arrests, and the local jurisdictions of law enforcement agencies in the data. In terms of crimes, particularly crimes in school, agencies that receive CIS grants are worse off than agencies that do not; overall official crime rates are higher for agencies that receive federal funding, although principals are less likely to say that students live in “high-crime” neighborhoods. Even relative to the general community, CIS agencies seem to serve schools that are disproportionately more dangerous than schools where agencies do not receive funding; school crimes make up a larger fraction of overall offenses in all crime categories, and school surveys reflect this as well. CIS agencies also received more UHP and technology grants (Making Officer Redeployment Effective, or MORE grants) than non-CIS agencies, consistent with one of the important mechanisms determining the timing and size of grants described in Evans and Owens (2007): the COPS office was relatively aggressive about distributing money to agencies that had demonstrated the ability to successfully spend grant money in the past.

| All agencies (n = 218,244) | CIS agencies (n = 54,948) | Non-CIS agencies (n = 163,296) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean | SD | Mean | SD | Mean | SD | |

| Agency measures | ||||||

| Violent crime rate | 10.44 | (11.08) | 11.20 | (10.50) | 10.19 | (11.25) |

| In schools, pre-1999 | 0.34 | (0.85) | 0.44 | (0.89) | 0.30 | (0.82) |

| Violent arrest rate | 4.63 | (5.18) | 5.31 | (5.49) | 4.40 | (5.05) |

| Property crime rate | 32.93 | (29.64) | 36.75 | (31.53) | 31.64 | (28.86) |

| In schools, pre-1999 | 0.84 | (1.61) | 1.05 | (1.72) | 0.76 | (1.56) |

| Property arrest rate | 5.64 | (7.82) | 6.59 | (8.19) | 5.33 | (7.66) |

| Drug crime rate | 4.10 | (5.35) | 4.59 | (5.50) | 3.94 | (5.29) |

| In schools, pre-1999 | 0.11 | (0.45) | 0.16 | (0.50) | 0.09 | (0.432) |

| Drug arrest rate | 4.16 | (6.09) | 4.63 | (6.13) | 4.00 | (6.07) |

| Weapon crime rate | 0.48 | (1.00) | 0.52 | (0.90) | 0.47 | (1.03) |

| In schools, pre-1999 | 0.03 | (0.18) | 0.04 | (0.19) | 0.03 | (0.19) |

| Weapon arrest rate | 0.40 | (0.92) | 0.43 | (0.87) | 0.38 | (0.93) |

| UHP grant rate | 0.27 | (0.95) | 0.32 | (1.01) | 0.26 | (0.93) |

| MORE grant rate | 0.35 | (1.12) | 0.50 | (1.21) | 0.30 | (1.08) |

| CIS grant rate | 0.053 | (0.286) | 0.212 | (0.541) | ||

| County measures | ||||||

| School revenue per population under 20 | 50.01 | (17.96) | 49.62 | (18.38) | 50.15 | (17.81) |

| People under 20 per school | 2,259.50 | (46,533.81) | 2,875.40 | (52,736.68) | 2,052.26 | (44,249.76) |

| High school grads per 15 to 19-year-olds | 0.14 | (0.05) | 0.14 | (0.05) | 0.14 | (0.05) |

| Students per teacher | 13.19 | (7.69) | 12.64 | (6.54) | 13.38 | (8.03) |

| Poverty rate | 11.90 | (4.69) | 11.33 | (4.27) | 12.09 | (4.81) |

| Child poverty rate | 14.54 | (6.66) | 13.89 | (6.20) | 14.76 | (6.79) |

| Real median income | 43,225.26 | (11,358.87) | 44,511.66 | (11,202.90) | 42,792.40 | (11,378.25) |

| Percentage nonwhite | 11.76 | (12.99) | 10.89 | (11.20) | 12.05 | (13.52) |

| Percentage nonwhite, 15 to 19-year-olds | 14.26 | (15.24) | 13.30 | (13.11) | 14.58 | (15.88) |

- Notes: Agency, crime, and arrest rates scaled by 10,000 people in jurisdiction as reported to UCR. County measures scaled by 10,000 county residents from intercensal estimates. All monetary values in real 2010 dollars. MORE grants are measured in $100 granted per person, and decay at a rate of 2. 5 percent/month. All other COPS grants are officers per 10,000 people. The mean pre-1999 differences in all measures (except for CIS grants) across CIS and non-CIS agencies are statistically significant, with p-values less than 0.001.

| All schools (n = 6,850) | CIS schools (n = 1,840) | Non-CIS schools (n = 5,010) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean | SD | Mean | SD | Mean | SD | |

| School measures | ||||||

| Violent incident rate | 3.628 | (9.949) | 3.799 | (5.66) | 3.566 | (11.115) |

| Police notified | 1.046 | (2.280) | 1.232 | (2.576) | 0.978* | (2.160) |

| Property incident rate | 1.221 | (1.976) | 1.172 | (2.01) | 1.239 | (1.963) |

| Police notified | 0.611 | (1.140) | 0.635 | (1.07) | 0.602 | (1.165) |

| Drug incident rate | 0.271 | (0.652) | 0.206 | (0.466) | 0.295* | (0.707) |

| Police notified | 0.233 | (0.547) | 0.176 | (0.386) | 0.254* | (0.593) |

| Weapon incident rate | 0.204 | (0.482) | 0.166 | (0.312) | 0.218* | (0.530) |

| Police notified | 0.133 | (0.154) | 0.124 | (0.261) | 0.138 | (0.413) |

| Security staff | 0.711 | 0.824 | 0.667* | |||

| CIS officers in county | 0.049 | (0.339) | 0.184 | (0.636) | ||

| Ln(total enrollment) | 6.558 | (0.762) | 6.759 | (0.690) | 6.484* | (0.774) |

| Likely to go to college | 57.836 | (24.947) | 57.887 | (25.977) | 57.817 | (24.561) |

| Limited English proficient | 8.452 | (14.554) | 11.013 | (16.754) | 7.513* | (13.540) |

| Nonwhite | 37.036 | (32.390) | 42.402 | (33.791) | 35.068* | (31.637) |

| Free or reduced lunch | 42.121 | (27.652) | 41.340 | (29.568) | 42.407 | (26.913) |

| Academic achievement very important | 68.198 | (22.705) | 68.039 | (23.002) | 68.256 | (22.598) |

| <15th percentile on standardized tests | 14.275 | (14.480) | 15.742 | (15.960) | 13.736 | (13.861) |

| Percentage male | 49.560 | (8.859) | 49.788 | (7.426) | 35.068* | (31.637) |

| Months in school year | 9.407 | (0.634) | 9.424 | (0.647) | 9.401 | (0.629) |

| Special education students | 13.547 | (8.420) | 11.013 | (16.754) | 13.733* | (8.635) |

| Crime where students live | ||||||

| High (percent) | 7.24 | 9.52 | 6.40 | |||

| Moderate (percent) | 21.22 | 24.42 | 20.05 | |||

| Low (percent) | 55.97 | 50.35 | 58.03 | |||

| Mixed (percent) | 15.57 | 15.72 | 15.52 | |||

| Type of school (percent) | ||||||

| Elementary (percent) | 22.55 | 20.28 | 23.38 | |||

| Middle (percent) | 35.51 | 37.36 | 34.83 | |||

| High school (percent) | 37.74 | 39.26 | 37.18 | |||

| Combined (percent) | 4.2 | 3.10 | 4.61 | |||

- Notes: School incident rates scaled by 10,000 students. County measures scaled by 10,000 county residents from intercensal estimates. Sample sizes rounded to nearest 10 to comply with IES data security protocol. Starred means (*) are statistically different (p < 0.05) across schools in counties that did and did not receive CIS grants.

Turning to school quality, districts associated with CIS agencies also appear to be worse off than non-CIS districts on some dimensions; revenue per potential student is lower and there are more students per school. At the same time, other common schooling measures are better in CIS districts. The student-teacher ratio is slightly lower in CIS districts, and there is the same number of high school graduates per young adult in both places. CIS agencies are also located in counties that have lower poverty rates, higher median income, and more white residents than non-CIS agencies. The SSOCS also does not clearly identify schools in CIS counties as systematically different; there are slightly more minority students, English-language learners, and poor test takers in school that receive CIS grants, but otherwise the principals’ assessments of the students are similar across groups.

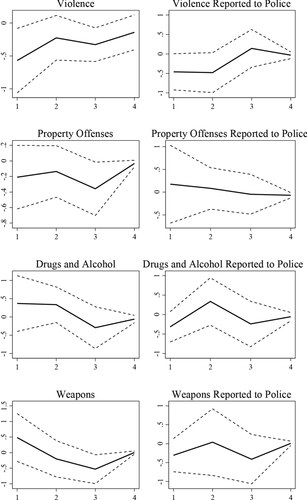

In Figure 1, I plot the mean number of monthly offenses, in and out of school, reported by agencies that did and did not receive CIS grants. I also indicate the earliest date at which an agency could have received a CIS grant (April of 1999). Even though total crime in the United States is falling during this time period, there is a slow drift upward in crime among all agencies, reflecting growing coverage of higher-crime areas in the NIBRS data over time. There is some evidence of a small increase in officially recorded crime in schools that received CIS officers, particularly after 2002.10 Figures 2 and 3 show monthly arrests, by age, made by officers in CIS and non-CIS agencies, for crimes committed inside and outside of school. CIS agencies do appear to arrest more people for crimes in schools after 1999, and, in particular, arrest more young people. This pattern is not evident in trends in arrests for crimes committed off school grounds, implying that once an SRO is hired, young people have a higher chance of being arrested for misbehavior in school, but it is not clear that SROs are associated with an increased likelihood of solving crimes in general.11 Clearly, CIS and non-CIS agencies have different crime environments, and also different schooling environments, but it is difficult to tell, a priori, to what extent measurable demographic differences, rather than trends in unobserved variables, can explain the observed differences in crime.

Figures 1 and 2, along with Tables 1 and 2, suggest that these average values are likely to be correlated with the number of CIS officers an agency receives, and in a cross-sectional setting would introduce bias into estimates of the impact of CIS grants on officially recorded crime and arrests. However, in a panel data setting like the current one, these time-invariant characteristics can be differenced out with an agency-specific fixed effect. On the other hand, if trends—my estimated values of Ф from equation 2—in these observed factors were predictive of COPS generosity, then this would raise concerns that unobserved, time-varying agency characteristics correlated with officially recorded crimes and arrests also systematically varies across agencies that did and did not receive grants. The estimated coefficients of equation 1 are in Appendix Table A1.12 Overall, these levels and trends explain only 6 percent of the variation in CIS awards, and while I am able to easily reject the null hypothesis that average values of demographic, education, and crime variables cannot jointly predict CIS grants (the F-statistic is 3.34, with a p-value of 0), I cannot reject the null hypothesis that trends in these values (or just the crime and arrest variables) are unrelated to the total amount of SROs granted to an agency (F = 0.95, p = 0.5199 or F = 1.01, p = 0.4230, respectively).

ANALYTIC FRAMEWORK

Consistent with Evans and Owens (2007), who examined different grants made by the same federal agency, local law enforcement agencies that received CIS grants were obviously different from those that did not, but there is no clear evidence of systematic trends in observable school, and demographic, or crime differences in cities that did or did not receive these grants. As a result, CIS grants can be used to estimate the impact of these particular officers on crime, in a way that will not be subject to the omitted variable and reverse causality bias that would arise from simply comparing schools with and without SROs.

where Crimeipscym is the crime or arrest rate (per 10,000 people) reported by law enforcement agency i, in population group p, in state s, county c, in year y and month m. The parameter of interest, β, represents the marginal impact of receiving a grant for one additional CIS officer from the COPS office that was active in year y and month m. I allow for arbitrary seasonality in crime that is common to agencies in similar-sized jurisdictions (between 5 and 10, 10 and 25, 25 and 50, 50 and 75, and 75 and 100 thousand residents on average) with a set of 600 (5 × 10 × 12) time dummies αpym, along with annual shocks to crime that are common to all agencies in the same state, γsy, and a level difference in the crime rate of each agency δi. I also allow for arbitrary variation in εipscym within a law enforcement agency by clustering at the agency level.

Finally, I include a measure of the number of active COPS grants that agency i received in year y and month m. I focus on the two largest programs, the COPS UHP and Making Officer Redeployment Effective Program. Consistent with Evans and Owens (2007), these variables are lagged by one year as the receipt of the grant involved substantial hiring, training, and investment on the part of the receiving agency.

My identification of β is therefore based on month-to-month within-agency variation in crime and arrests that is correlated with the receipt of CIS grants, but is not correlated with any variation in the demographics of the areas the agency patrols, or in changes in school expenditures or standard measures of school quality. My fixed effect specification differences out unobserved time-varying features common to agencies of similar size (e.g., changes in “best practices” recommendations from national advisory agencies) or in the same state (e.g., changes in the age of majority). Of course, I cannot rule out the presence of other unobserved time-variant shocks, but since graphical and regression analysis of pretreatment trends failed to uncover systematic variation across agencies that did and did not receive CIS grants, any such unobserved factors must have been introduced after 1999, when the first CIS grant was awarded.

RESULTS

CIS Grants and Police Employment

Before examining the impact of CIS grants on crime, I am able to shed some light on the impact of CIS grants on police employment by presenting estimates of equation 3, where the outcome variable is officer employment. I measure officer employment in four ways. First, using the sample of law enforcement agencies reporting to the NIBRS, I estimate the impact of receiving a grant on the total number of sworn police officers, as measured in the UCR. The UCR reports the total number of sworn officers employed by the police agency as of October 7 of each year, which includes all employees with arrest powers, from beat officer to chief. While total officer employment is a noisy measure of the number of SROs hired, I am able to observe this value for each agency in every year in my sample, allowing me to estimate the impact of CIS grants on employment conditional on a relatively rich set of observables and a full set of time and agency fixed effects.

My next source of information on police officer employment is the LEMAS. The overlap between the LEMAS and NIBRS is not very large; all police agencies with more than 100 sworn officers are surveyed in every LEMAS round, and only a representative sample of smaller agencies, which are more likely to be represented in the NIBRS, are included in each LEMAS survey. While the LEMAS measures the outcome variable of interest with precision, the repeated cross-sectional nature of the data limits my ability to use a full set of fixed effects. The SSOCS data on placement of SROs are even more limited; identification of the impact of CIS officers on SRO school staffing in this sample relies on law enforcement agencies that receive CIS grants and then decide to place an SRO in a school that happens to be selected in the nationally representative SSOCS sample.

These estimates are presented in Table 3. Each additional CIS officer granted was associated with 1.5 (se = 0. 86) additional officers being hired, a large effect that is statistically significant at the 10 percent level.13 In contrast, agency response to UHP grants was a smaller, but much more precisely estimated 1.11 officers per award (se = 0.412). Agencies that received grants for technology and support staff also increased slightly in size, with roughly 0.13 additional officers (se = 0.051) being hired for each million dollars awarded through MORE (the average MORE grant was roughly $65,000).14 The large, but somewhat imprecisely estimated, relationship between CIS grants and total officer employment is consistent with the institutional differences across COPS grant programs. UHP grants were explicitly to hire new officers. CIS grants, on the other hand, were intended to support the salary of an officer who was stationed in a local school. Complying with a CIS grant does not necessarily require hiring more police officers, but the shift in officer deployment could lead to agencies petitioning their local government to increase their overall officer complement.

| Sworn officers per 10,000 residents (mean = 18.4) | SROs per 10,000 residents (mean = 0.66) | SROs per sworn officer (mean = 0.037) | Any school security officers (mean = 0.711) | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CIS officers granted | 1.536+ | 0.643*** | 0.624*** | 0.385** | 0.030*** | 0.029*** | 0.021** | 0.0386** |

| (0.899) | (0.068) | (0.068) | (0.118) | (0.006) | (0.006) | (0.008) | [0.0138] | |

| Lag UHP officers granted | 1.111** | 0.004 | 0.005 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.00643 |

| (0.412) | (0.005) | (0.006) | (0.001) | (0.000) | (0.000) | (0.000) | [0.0108] | |

| Lag MORE dollars granted | 0.130* | 2.133 | 2.271 | Ǡ0.240 | −0.014 | −0.008 | 0.011 | |

| (0.051) | (1.459) | (1.461) | (0.865) | (0.051) | (0.050) | (0.046) | ||

| Year fixed effects | x | x | x | x | x | x | ||

| Agency/school fixed effects | x | x | x | |||||

| State by year fixed effects | x | |||||||

| Pop. size group fixed effects | x | |||||||

| N | 18,187 | 8,990 | 8,990 | 8,990 | 8,990 | 8,990 | 8,990 | 6,850 |

| Agencies/schools | 2,310 | 3,828 | 3,828 | 3,828 | 3,828 | 3,828 | 3,828 | 6,450 |

| R2 | 0.83 | 0.03 | 0.04 | 0.62 | 0.02 | 0.02 | 0.52 | 0.325 |

- Notes: Additional county-level controls in columns 1, and 3 through 7 include school district revenue per resident under the age of 20 ($2,010), residents under 20 per public and charter school, high school graduates per resident under 20, school district teacher to student ratio, poverty rate, children poverty rate, median income ($2010), percentage nonwhite, and percentage of residents under 20 who are nonwhite. Standard errors in parenthesis allow for arbitrary correlation in dependent variable within agency. Additional school level controls in column 2 include school year and school type fixed effects, dummy variables for perceived level of crime in students’ neighborhoods, Ln(total school enrollment), months in school year, and controls for the percentage of the student body that is male, minority, scores below the 15th percentile on standardized tests, is an English-language learner, is enrolled in special education, is college bound, and considers academic achievement to be important. Standard errors in brackets allow for arbitrary correlation in outcomes within county. Observations are not weighted, so estimates reflect correlations within SSOCS sample only. SSOCS total sample size rounded to nearest 10 to comply with IES Data Security Protocol.

- +p < 0.10; *p < 0.05; **p < 0.01; ***p < 0.001.

In the next columns of Table 3, I present estimates of the impact of CIS grants on SRO employment in the LEMAS, both in terms of the number of SROs per 10,000 residents and the fraction of officers in the police department that are stationed in schools. When I do not include agency fixed effects, receiving one additional CIS officer almost doubles the number of SROs (0. 624 additional SROs per CIS officer granted, se = 0.068) an agency employs within one month. When I limit my identification to the 363 agencies (about 10 percent of the total sample) that I observe both with and without a grant, one additional CIS officer is associated with 0.385 (se = 0.118) additional SROs, a 58 percent increase, within one month. Roughly 4 percent of sworn officers in LEMAS are SROs, and on average, a CIS officer will increase that fraction by 2 to 3 percentage points, which is also consistent with agencies hiring new officers to fill these positions (or replacing experienced officers who become SROs), rather than simply reshuffling existing employees. There is essentially no relationship between other COPS grants and SRO employment.

Finally, I estimate the impact of county-level CIS grants on school security. I pool all three waves of data, and in lieu of school fixed effects (only 7 percent of schools are surveyed more than once), use school-level, as opposed to county- or agency-level, control variables and cluster my observations at the county level in these regressions.15 The typical CIS grant to agencies in the county where a surveyed school is located (roughly 0.18 officers per 10,000 residents) is associated with 0.7 percentage point increase (se = 0.2) in the probability that a school administrator in that county reports having paid security or law enforcement, roughly 1 percent relative to the sample mean. This relatively small effect is not surprising, as the practical link between county-level CIS grant receipt and security staff in any given school is probabilistic at best. However, there is essentially no relationship between UHP grants and school security, which does provide some evidence that CIS grants are influencing school staffing decisions, rather than simply being correlated with trends in underlying crime, police staffing, or local government revenue.16

CIS Grants, School Safety, and Reported Crime

After showing that CIS grants are associated with an increase in SRO employment at the police agency level, and also an increase in the presence of security in local schools, I now turn to the reduced form impacts of these grants on the school environment. If SROs promote trust between officers and young people and encourage them to report crimes that previously would have gone unreported and unpunished, we would expect CIS grants to be associated with more officially reported crimes in and out of school, and also potentially more arrests associated with those crimes. Alternately, if SROs simply relabel misbehavior at school as crime, we would expect to see an increase in officially recorded crimes and arrests in school, but not outside school. The relabeling of disruptive behavior as crime warranting an arrest should also only affect young people, whereas improved community relationships could plausibly lead to more arrests of people of all ages. Of course, both of these mechanisms implicitly assume that the presence of SROs does not alter the behavior of students—to the extent that SROs actually deter criminal behavior, we may see a reduction in actual crimes.

Survey Data on School Safety

My estimates of the impact of CIS officers on different dimensions of crime in schools are presented in Table 4. I begin with survey data on the number of violent or property incidents, along with the number of times intoxicants (drugs or alcohol) or weapons were found on students. As in the previous table, I define my CIS variable as the average number of officers subsidized by CIS in the county where the school was located, during the months that school was in session. In contrast with existing research, I find evidence that CIS officers increase school safety; administrators in counties with more CIS officers are less likely to report all types of incidents, and the reductions in violent, property, and weapons offenses would occur less than 10 percent of the time under the null hypothesis of no impact.17 In terms of magnitudes, I find that the average grant is associated with a 1.1 percent to 1.9 percent reduction in disruptive criminal incidents in school.

| School administrator's annual report 2003 to 2004, 2005 to 2006, 2007 to 2008 All incidents (SSOCS, n = 6,850) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Violent | Property | Drugs | Weapons | |

| CIS officers granted | −0.333+ | −0.128** | −0.0291 | −0.0156+ |

| [0.192] | [0.0398] | [0.0292] | [0.00854] | |

| Mean of DV | 3.63 | 1.22 | 0.488 | 0.204 |

| R2 | 0.0748 | 0.0922 | 0.149 | 0.0836 |

|

School administrator's annual report 2003 to 2004, 2005 to 2006, 2007 to 2008 Police contacted (SSOCS, n = 6,850) |

||||

| CIS officers granted | −0.0598 | −0.0457* | −0.0291 | −0.00895 |

| [0.0406] | [0.0201] | [0.0217] | [0.00769] | |

| Mean of DV | 1.04 | 0.611 | 0.401 | 0.134 |

| R2 | 0.115 | 0.0722 | 0.14 | 0.0659 |

| Implied change in reporting likelihood | 0.65% | 0.56% | −0.24% | 0.18% |

|

Official monthly police record, 1997 to 2007 In school (NIBRS, n = 218,244) |

||||

| CIS officers granted | 0.060** | 0.099 | 0.022+ | 0.009* |

| (0.022) | (0.065) | (0.012) | (0.005) | |

| Mean of DV | 0.425 | 0.816 | 0.151 | 0.036 |

| R2 | 0.34 | 0.38 | 0.19 | 0.09 |

|

Official monthly police record, 1997 to 2007 Out of school (NIBRS, n = 218,244) |

||||

| CIS officers granted | 1.059 | 3.900 | 0.424+ | 0.019 |

| (0.745) | (3.217) | (0.250) | (0.013) | |

| Mean of DV | 10.0 | 32.1 | 3.95 | 0.449 |

| R2 | 0.77 | 0.73 | 0.55 | 0.32 |

- Notes: SSOCS regressions include school year and school type fixed effects, dummy variables for perceived level of crime in students’ neighborhoods, Ln(total school enrollment), months in school year, and controls for the percentage of the student body that is male, minority, scores below the 15th percentile on standardized tests, is an English-language learner, is enrolled in special education, is college bound, and considers academic achievement to be important. Standard errors in brackets allow for arbitrary correlation in outcomes within county (1,750 clusters). Observations are not weighted, so estimates reflect correlations within SSOCS sample only. SSOCS sample sizes rounded to nearest 10 to comply with IES Data Security Protocol. NIBRS regressions include agency fixed effects, month by population size group fixed effects, and state by year fixed effects. Additional county level controls include school district revenue per resident under the age of 20 ($2,010), residents under 20 per public and charter school, high school graduates per resident under 20, school district teacher to student ratio, poverty rate, children poverty rate, median income ($2,010), percentage nonwhite, and percentage of residents under 20 who are nonwhite. Additional agency controls include UHP officers granted last year, and total MORE awards ($2,010) per capita decaying at a rate of 2.5 percent/month since award. Standard errors in parenthesis allow for arbitrary correlation in dependent variable within agency (2,310 clusters).

- +p < 0.10; *p < 0.05; **p < 0.01; ***p < 0.001.

As shown in the second panel of Table 4, CIS grants are also associated with fewer crimes being reported to law enforcement, although the magnitude of the reductions is smaller in absolute value and is less precisely estimated, than the estimated reduction in actual behaviors.

In order to calculate whether or not this reduction in reported crime constitutes a change in the probability that a given crime is reported, I construct an implied change in reporting rate using a back-of-the-envelope calculation, [(1 + ε(Report CIS))/(1 + ε(Crime CIS))] – 1, where ε(Crime CIS) is my estimate of the percentage change in total crime associated with an average CIS grant, and ε(Reported CIS) is the similar change in reported crime.18 This calculation suggests that CIS grants are associated with small increases, a fraction of a percentage point, in the rate at which law enforcement is contacted about most school problems that do occur. The exception is disruptions involving drugs or alcohol, where that is one-fourth of a percentage point reduction in the probability that an administrator alerts the police. These changes are also imprecisely estimated, and 95 percent confidence intervals for each point estimate range from roughly –1.5 to 2 percentage points.

Official Police Records of Crime

School survey data suggest one real benefit of SROs is an increase in school safety. However, this increase in safety is not free; it is accompanied by a small increase in the probability that students who continue to engage in disruptive and harmful behavior will come into contact with the formal criminal justice system, rather than the principal's office. Whether or not police learn about more offenses when schools have SROs can be directly tested with the NIBRS data.

In the third panel of Table 4, we observe that CIS grants are associated with statistically significant increases in the number of officially recorded violent, drug, and weapons crimes taking place in schools, with effects sizes ranging from 12 and 25 percent per CIS officer, or 2.1 percent and 4.3 percent increase in crimes associated with a 10 percent increase in SROs. When compared to the school survey results, this tells us that, even if school safety is increasing, the response to incidents that do occur is such that, on net, police observe more offenses than before SROs were put in place. This is particularly striking for violent and weapons offenses, where one additional CIS officer is associated with 0.333 (se = 0.192) fewer violent incidents and 0.016 (se = 0.008) fewer weapons violations as reported by principals, but 0.06 (se = 0.022) more violent incidents and 0.009 (se = 0.005) more weapons violations known to police. The magnitude of both reductions would be observed less than 10 percent of the time under the null hypothesis of no relationship between CIS officers and this outcome, and the increases in offenses known to police would both be observed less than 5 percent of the time under the same null hypothesis.

In the fourth panel of Table 4, I examine whether or not this change in the formal response to crime occurs off school grounds as well. While the point estimates on crimes taking place outside school suggest that hiring SROs might increase police awareness of all crimes, only the 10 percent increase (in the reduced form) in awareness of drug crimes is statistically significant at conventional levels (p = 0.09).19 It is noteworthy that this is consistent with SROs learning about the existence of local drug markets from students who are caught with drugs in school; a student committing a violent offense, or bringing a weapon to school, does not necessarily have information about off-campus crimes.

Setting precision aside, in percentage terms I estimate a 12 percent increase in police knowledge of property offenses both on and off school grounds. This equivalence in effect size is consistent with, in some jurisdictions at least, SROs learning about more property crimes because school-aged children are more likely to talk to the police generally. However, I do not find evidence that this is a general effect; for violent and drug offenses, the increase in awareness of crimes on school grounds is about a third larger than the increased awareness of crimes in the community (11 percent versus 14 percent), and the increased awareness of weapons offenses on campus is almost five times larger than the increased awareness of guns in the neighborhood. Unlike the more general UHP hiring grants distributed by the COPS office, which were associated with both lower crime and lower arrest rates (Evans & Owens, 2007; Owens, 2013), the increases in school safety associated with SROs may have come at a much larger cost.

CIS Grants and Arrests

In Table 5, I examine how police agencies that receive CIS grants make arrests for violent crimes, based on where the crime occurred and how old the person arrested was. Since not all arrests of people under the age of 18 result in formal processing, I also examine the impact of CIS grants on the rate at which people are actually booked, rather than informally handled (e.g., by calling the juvenile's parents), both of which are recorded in the data.

| In school | Out of school | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total arrests | ||||||||

| Violent | Property | Drugs | Weapons | Violent | Property | Drugs | Weapons | |

| CIS officers granted | 0.025+ | 0.020+ | 0.025* | 0.007+ | 0.532 | 0.309 | 0.369+ | 0.012 |

| (0.014) | (0.011) | (0.012) | (0.004) | (0.396) | (0.198) | (0.212) | (0.014) | |

| Mean of DV | 0.183 | 0.144 | 0.130 | 0.022 | 4.45 | 5.4 | 4.02 | 0.374 |

| R2 | 0.27 | 0.13 | 0.17 | 0.07 | 0.63 | 0.58 | 0.54 | 0.29 |

| Young adults (15 to 19 years old)—total arrests | ||||||||

| CIS officers granted | 0.093 | 0.071 | 0.208+ | 0.058 | 1.638 | 1.538 | 1.730* | −0.052 |

| (0.105) | (0.058) | (0.110) | (0.044) | (1.314) | (0.984) | (0.796) | (0.081) | |

| Mean of DV | 1.24 | 0.984 | 1.21 | 0.164 | 9.56 | 22.3 | 13.9 | 1.28 |

| R2 | 0.18 | 0.08 | 0.14 | 0.05 | 0.37 | 0.29 | 0.33 | 0.14 |

| Young adults (15 to 19 years old)—arrested and booked | ||||||||

| CIS officers granted | 0.060 | 0.048 | 0.197+ | 0.052 | 1.574 | 1.454 | 1.508+ | −0.087 |

| (0.107) | (0.053) | (0.107) | (0.043) | (1.317) | (0.919) | (0.780) | (0.070) | |

| Mean of DV | 1.00 | 0.809 | 0.978 | 0.135 | 8.33 | 19.0 | 12.4 | 1.12 |

| R2 | 0.17 | 0.07 | 0.13 | 0.05 | 0.35 | 0.27 | 0.33 | 0.13 |

| Minors (7 to 14 years old)—total arrests | ||||||||

| CIS officers granted | 0.079* | 0.071* | 0.051+ | 0.012 | 0.275 | 0.187 | 0.021 | 0.000 |

| (0.037) | (0.034) | (0.029) | (0.008) | (0.178) | (0.144) | (0.015) | (0.008) | |

| Mean of DV | 0.378 | 0.264 | 0.159 | 0.042 | 0.935 | 2.34 | 0.197 | 0.068 |

| R2 | 0.21 | 0.09 | 0.08 | 0.04 | 0.29 | 0.26 | 0.07 | 0.08 |

| Minors (7 to 14 years old)—arrested and booked | ||||||||

| CIS officers granted | 0.061+ | 0.048+ | 0.043 | 0.010 | 0.233 | 0.162 | 0.012 | −0.004 |

| (0.032) | (0.028) | (0.028) | (0.008) | (0.176) | (0.147) | (0.013) | (0.007) | |

| Mean of DV | 0.296 | 0.206 | 0.123 | 0.033 | 0.687 | 1.70 | 0.140 | 0.048 |

| R2 | 0.19 | 0.09 | 0.08 | 0.04 | 0.27 | 0.23 | 0.06 | 0.06 |

- Notes: All regressions contain 218,244 observations, and include agency fixed effects, month by population size group fixed effects, and state by year fixed effects. Additional county-level controls include school district revenue per resident under the age of 20 ($2,010), residents under 20 per public and charter school, high school graduates per resident under 20, school district teacher to student ratio, poverty rate, children poverty rate, median income ($2,010), percentage nonwhite, and percentage of residents under 20 who are nonwhite. Additional agency controls include UHP officers granted last year, and total MORE awards ($2,010) per capita decaying at a rate of 2.5 percent/month since award. Standard errors in parenthesis allow for arbitrary correlation in dependent variable within agency (2,310 clusters).

- +p < 0.10;*p < 0.05;**p < 0.01;***p < 0.001.

Not only do police learn of more crimes in schools, they also make more arrests for these offenses. Each additional CIS officer is associated with 0.025 (se = 0.014) additional arrests being made, or roughly one additional charge every four and a half school years. A 21 percent increase (se = 0.098) in the arrests of minors, children under the age of 15, is driving this—agencies that receive a grant for one CIS officer per 10,000 residents arrest one additional person under the age of 15 every year, and three additional children every two school years. The marginal minor arrested also appears to be formally booked, rather than simply referred to their parents. I do not observe any consistent change in arrest rates for violent crime that takes place outside schools, although in percentage terms, the imprecise point estimates are actually larger; this suggests that, relative to arrests in schools, there is potentially a fair amount of heterogeneity in how police officers interact with youth more broadly after SROs are hired.

I also find that while police do not appear to learn of any additional property crimes when they receive CIS grants, they do make more arrests for property offenses, particularly those that occur on school grounds, roughly 0.02 additional charges (se = 0.01) per CIS officer granted (or about 0.04 per SRO). CIS grants do not appear to help police departments make arrests for off-campus property crimes. Again, however, the increase in arrests is due to an increase in the number of children under 15. Each additional CIS officer is associated with 0.07 arrests (se = 0.034) being made (per 10,000 young adults and minors), and 0.048 additional formal bookings (se = 0.028). I cannot reject the null hypothesis of no change in arrests for off-campus property crimes, and the effect sizes in percentage terms are also much smaller.

The only off-campus crime that police learn about when they receive CIS grants are drug offenses. These grants also appear to allow officers to make more arrests for drug crimes, although in percentage terms the increase in arrests for on-campus drug crimes is always larger. The people being arrested for drug crimes appear to be older than those arrested for violent or property crimes; there are statistically significant increases in the arrest rates for 15- to 19-year-olds on and off school grounds, corresponding to 1.7 additional arrests (per 10,000 15- to 19-year-olds, se = 0.0796) for off-campus drug crimes per CIS officer granted, or 4.47 per SRO. Minors under the age of 15 are more likely to be arrested for drug crimes in school when agencies receive CIS grants, but there is no clear increase in formal bookings or off-campus arrests for drugs among this age group. To the extent that 14-year-olds are less likely to sell drugs than young adults, and that students may buy their drugs from slightly older peers, this pattern of arrests is additional evidence that SROs learn about ancillary drug crimes in the community from interacting with, and sometimes arresting, students in the schools they patrol.

Law enforcement officials both learn of, and make more arrests for, weapons violations in schools when they receive CIS grants. However, unlike other crimes, the age of those arrested suggests that adults, rather than children, are more likely to be arrested for having a weapon on school grounds. I observe that each additional CIS officer granted is associated with a moderately significant 0.007 increase (se = 0.004) in the number of arrests for weapons violations on school grounds a month. However, I do not observe a statistically significant increase in the in-school arrest rates for weapons violations by young adults or minors.

Taken as a whole, the data imply that law enforcement agencies that place officers in schools learned about more criminal offenses on school grounds. They also made more arrests, and in particular arrests of young people for crimes on campus, including many students less than 15 years old. The observed arrest patterns suggest that, even when endogenous hiring of SROs is addressed, adding police officers to schools results in more children being arrested and does not obviously increase the likelihood that young people contact officers about crime in their community, on average. The exception to this is drug charges, where police do appear to be able to identify and arrest more young adults for off-campus drug crimes.

School Safety, Crime, and Arrests by County Demographics

Between 2006 and 2010, black and Hispanic crime victims were more likely to report crimes to the police than white crime victims. However, black and Hispanic victims who did not report a crime were more likely to cite mistrust of the police as a reason (Langton et al., 2012). This is consistent with surveys of social attitudes, which typically find that minorities are less likely to place a great deal of trust in the police as an institution.20 A highly relevant policy question, therefore, is whether or not there is systematic variation in the relationship among SROs, school safety, and officially recorded crimes in areas with more nonwhite people. Heterogeneity in the impact of SROs on police-community relations may also explain the large, but imprecise, impact of CIS officers on off-campus policing.

The SSOCS and NIBRS data provide suggestive, but ultimately inconclusive, evidence that CIS officers may actually improve police-community relationships in places with larger black and Hispanic populations. Estimating equation 3 in subsamples of SSOCS and NIBRS data (based on the average percentage of young adults who are nonwhite) yields effects of CIS officers on crimes, as well as arrests, outside of school that are qualitatively larger in places with more minorities. However, the estimates are statistically indistinguishable from one another. The relationship between CIS officers and officially recorded crimes in school, as well as reports of crimes by principals, is more constant across jurisdictions, although there may be less of a deterrent effect of CIS officers in schools with more minority students. Appendix Figures A13 through A15 present the standardized effect sizes, along with 95 percent confidence intervals, for jurisdictions with increasingly larger black and Hispanic populations.21 While these figures are consistent with the School-to-Prison Pipeline being weaker in areas with larger minority populations, additional data on the activities of SROs in urban and minority school districts will be necessary to draw firmer conclusions.

Estimated Impact of CIS Officers on School Safety, by Nonwhite Quartile, in 2003 to 2004, 2005 to 2006, and 2007 to 2008 SSCOS samples.

Notes: Nonwhite quartiles are based on school enrollment. Dashed lines represent 95 percent confidence intervals for point estimates. Point estimates and standard errors are scaled by dependent variable mean.

Estimated Impact of CIS Officers on Crime, by Location and Nonwhite Quartile.

Notes: Nonwhite quartiles are based on average percentage of 15- to 19-year-old population in the county that is not white. Dashed lines represent 95 percent confidence intervals for point estimates. Point estimates and standard errors are scaled by dependent variable mean.

Estimated Impact of CIS Officers on Arrests, by Location and Nonwhite Quartile.

Notes: Nonwhite quartiles are based on average percentage of 15- to 19-year-old population in the county that is not white. Dashed lines represent 95 percent confidence intervals for point estimates. Point estimates and standard errors are scaled by dependent variable mean.

CONCLUSION

Rapidly increasing crime rates in the 1980s and 1990s, particularly among young adults, led to an expansion in the scope of law enforcement, with sworn police officers replacing security guards in private buildings and in schools. The placement of police officers in schools, a practice that has been used in some school districts since the 1960s, was promoted by the federal government as a way to both increase school safety and also increase the chance that young adults, who rarely report crime to police officers, saw police in general as trustworthy and helpful. Today, as crime rates have fallen, and the racially disparate impact of anticrime laws passed in the 1990s has become better known, there has been a growing concern that SROs simply create a School-to-Prison Pipeline, where young people are arrested for behavior that previously would simply result in school discipline.

To date, evidence on the impact of SROs on crime and arrests has been limited to correlational studies that fail to address any bias generated by the simultaneous determination of school problems and SRO employment. Using credibly exogenous variation in SROs generated by DOJ hiring grants, I find that adding officers to schools appears to increase both school safety and police involvement in violent, drug, and weapons violations on school grounds, with some additional awareness of drug crimes and serious violent offenses happening in the community at large. I observe an increase in arrests that take place in schools when SROs are added. Even though people under 15 make up only a small fraction of those arrested, increases in arrest rates for children under the age of 15 are the most precisely estimated, and each CIS officer granted per 10,000 residents corresponds with roughly 0.213 additional charges per 10,000 minors being filed for in-school crimes in each school year. In addition, I find that arrests are for violent crimes that could be reasonably characterized as scuffling, rather than acts of life-threatening violence.

Introducing police officers into schools does appear to change the dynamics of the school environment, and does lead to an increase in the arrest rates of young children, particularly for minor offenses that happen to occur on school grounds. At the same time, there is some evidence to suggest that these officers can have a positive effect on the ability of local police to do their jobs outside of the school day, particularly when it comes to disrupting drug markets or making arrests for serious violent offenses. In addition, the largest increases in crime reporting off campus occur in communities with fewer white people. The nature of available data on SRO employment and police activity limits my ability to draw strong conclusions about the underlying mechanisms of these observed changes, or extrapolate to larger, more urban jurisdictions with larger minority populations. Future research that more precisely quantifies the effect that CIS grants have on the employment of SROs, along with the increased availability of location-specific crime data, will help clarify these issues.

Decisions about whether or not the benefit of school safety and improved police relations outweigh the cost of criminal justice involvement of minors should be left to policymakers in individual jurisdictions based on the specific needs of their locality; summary estimates of the social cost of crimes are predicated on adult victims, focusing on days of lost work and jury awards, and quantification of the impacts of disrupted educational attainment and future criminal involvement for those arrested are, to the best of my knowledge, currently not available. However, the simple conclusion that SROs are always good or bad for school children is not supported by the data.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

I thank Amanda Agan, John Donohue, Mathew Freedman, Tom Miles, Kenneth Couch, and three anonymous referees along with seminar participants at the NYU-Furman Center and the American Law and Economics Association for helpful comments. This research was conducted while I was an associate professor of criminology, business, economics, and public policy at the University of Pennsylvania. All errors are my own.

APPENDIX

| Trends | Average values | |

|---|---|---|

| School revenue per capita | 0.106 | −0.046 |

| (0.143) | (0.051) | |

| Residents under 20 per school | 0.015 | 0.000 |

| (0.017) | (0.000) | |

| High school graduates per resident 15–20 | −26.690 | −5.745 |

| (29.205) | (11.411) | |

| Teacher-student ratio | −0.172 | −0.236** |

| (0.170) | (0.078) | |

| Poverty rate | 0.488 | −0.405 |

| (1.147) | (0.532) | |

| Child poverty rate | −0.499 | 0.415 |

| (0.721) | (0.340) | |

| Median income | −0.000 | 0.000 |

| (0.001) | (0.000) | |

| Percentage nonwhite | −3.090 | −0.393 |

| (2.626) | (0.382) | |

| Percentage of 15- to 20-year-old nonwhite | −1.729 | 0.272 |

| (2.243) | (0.325) | |

| Lag UHP officers per rate | −0.152 | 0.327 |

| (0.590) | (0.317) | |

| Lag MORE grant ($1,000) rate | 0.007 | 1.428 |

| (0.602) | (1.859) | |

| Total crime rate | 0.022 | −0.018 |

| (0.055) | (0.026) | |

| Total arrest rate | −0.216+ | 0.159 |

| (0.112) | (0.123) | |

| Total crime rate, in schools only | −0.108 | 1.229+ |

| (0.832) | (0.693) | |

| Total arrest rate | 1.587 | −2.899+ |

| (1.170) | (1.637) | |

| Violent crime rate | 0.241 | 0.011 |

| (0.247) | (0.119) | |

| Violent crime rate, in schools only | −1.743 | −1.476 |

| (1.940) | (1.843) | |

| Arrests rate for violent crimes | 0.025 | −0.180 |

| (0.381) | (0.302) | |

| Arrest rate for violent crimes in schools | 1.354 | 7.294* |

| (3.625) | (3.509) |

- Notes: Estimated coefficients from a single regression that includes both trends and levels. All rates calculated per 10,000 residents. Robust standard errors in parentheses. R2 = 0.0586, F (38,1269) = 2.33.

- +p < 0.10; *p < 0.05; **p < 0.01; ***p < 0.001.

| Violent | Property | Drugs | Weapons | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total incidents—OLS | ||||

| School security | 1.055+ | 0.291*** | 0.132*** | 0.0779** |

| [0.539] | [0.0791] | [0.0378] | [0.0256] | |

| R2 | 0.0762 | 0.0948 | 0.151 | 0.0871 |

| Total incidents—2SLS | ||||

| School security | −8.616* | −3.304*** | −0.753 | −0.405+ |

| [4.026] | [0.898] | [0.933] | [0.237] | |

| Reported to police—OLS | ||||

| School security | 0.491*** | 0.228*** | 0.121*** | 0.0723** |

| [0.0818] | [0.0342] | [0.0309] | [0.0241] | |

| R2 | 0.122 | 0.0776 | 0.143 | 0.0709 |

| Reported to police—2SLS | ||||

| School security | −1.55 | −1.185 | −0.753 | −0.232 |

| [1.251] | [0.741] | [0.676] | [0.199] | |

- Notes: All regressions include school year and school type fixed effects, dummy variables for perceived level of crime in students’ neighborhoods, Ln(total school enrollment), months in school year, and controls for the percentage of the student body that is male, minority, scores below the 15th percentile on standardized tests, is an English language learner, is enrolled in special education, is college bound, and considers academic achievement to be important. Standard errors in brackets allow for arbitrary correlation in outcomes within county (1,750 clusters). Observations are not weighted, so estimates reflect correlations within SSOCS sample only. SSOCS sample sizes rounded to nearest 10 to comply with IES Data Security Protocol.

- +p < 0.10; *p < 0.05; **p < 0.01; ***p < 0.001.

Biography

EMILY G. OWENS is an Associate Professor in the Departments of Criminology, Law and Society, and Economics at the University of California, Irvine, 2340 Social Ecology II, Irvine, CA 92697 (e-mail: [email protected]).