Efficiency evaluation of the pension funds: Evidence from India

Abstract

The purpose of this article is to investigate the technical efficiency of Indian pension funds using data envelopment analysis (DEA) and to assess the reasons of inefficiency if any. This article analyzes the efficiency performance of all the pension funds available to Indian subscribers from the year 2015–2019 using radial measurers (BCC) of DEA based on secondary data collected from the annual reports of New Pension System Trust. Findings indicate that the average efficiency of Indian pension funds was 75.38% and this sector experienced overall stability in the average efficiency levels during the study period. Almost 40% of the pension funds operated efficiently in one or more years during the study period. The minimum slack was found in the input “expense ratio.” This confirms that risk associated with investments is the cause of inefficiency and not the expense ratio in the Indian pension sector. Tobit regression is applied to explore the main drivers of efficiency in the India pension funds. The study finds that fund size has positive association with the efficiency of the pension funds. Public sector funds were more efficient than the private sector funds. This study is first of its kind that has assessed the efficiency of Indian pension funds. The study brings into light the operating characteristics and efficiencies of the Indian pension funds for the period 2015–2019 and therefore holds important insights for policy makers, practitioners, and decision-makers.

1 INTRODUCTION

The pension sector in India has great potential and is one of the fastest-growing sectors of the Indian financial system. India has been a late starter in introducing a regulatory framework and a universal pension plan. Indian pension sector has mainly covered organized sector, almost 10% of the Indian population that means there is tremendous potential in the Indian pension sector. Initially, the Indian pension industry offered “defined benefit” (DB) pension plans to the central government (CG), state government (SG), and public sector employees. DB pension system was stressing the Indian fiscal system and there was also need to provide pension schemes in the unorganized sector of the economy. Therefore, the government of India established pension funds regulatory and development authority (PFRDA) in the Indian pension sector. PFRDA introduced a new pension scheme (NPS) in 2004 for government employees in India. Later on, it was opened for all the sections of the society in the year 2009. NPS is now open for both organized as well as unorganized sector.

The NPS achieved impressive growth of 35.65% in their asset under management (AUM) during the year 2018–2019 as compared to the previous year 2017–2018. All the pension funds recorded double-digit growth. The detail of AUMs under various schemes is given below in Table 1. As is evident from Table 1, AUM of CG, SG, Atal Pension Yojana (APY), and Scheme A Tier I (A1) schemes posted high growth of 28.32%, 36.98%, 79.69%, and 198.77%, respectively.

| Sr. no. | Scheme | 2015 | 2016 | 2017 | 2018 | 2019 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Equity Tier I (E1) | 6545.0 | 11,814.6 | 25,389.8 | 43,082.2 | 72,342.1 |

| 2 | Equity Tier II (E2) | 435.4 | 604.4 | 1259.0 | 2177.8 | 3254.4 |

| 3 | Bonds Tier I (C1) | 4687.6 | 8877.8 | 16,849.5 | 28,465.5 | 44,220.7 |

| 4 | Bonds Tier II (C2) | 374.8 | 551.0 | 1013.3 | 1621.6 | 2090.8 |

| 5 | Govt. Sec Tier I (G1) | 7712.9 | 13,247.9 | 25,069.3 | 42,430.6 | 68,967.5 |

| 6 | Govt. Sec Tier II (G2) | 356.8 | 543.5 | 1124.3 | 1814.7 | 2626.9 |

| 7 | Scheme A Tier I (A1) | — | — | 10.4 | 65.3 | 195.2 |

| 8 | Scheme A Tier II (A2) | — | — | 1.0 | — | — |

| 9 | NPS Lite | 16,057.2 | 21,075.5 | 26,392.1 | 30,058.2 | 34,092.3 |

| 10 | Corporate CG (CCG) | 41,051.2 | 68,050.5 | 10,7534.7 | 14,8463.3 | 20,6828.3 |

| 11 | Central Govt (CG) | 36,7367.7 | 48,1347.8 | 67,0400.5 | 84,9546.0 | 1,09,0107.0 |

| 12 | State Govt (SG) | 36,3962.6 | 57,6925.0 | 85,1714.3 | 1,15,9884.8 | 1,58,8811.1 |

| 13 | Atal Pension Yojana (APY) | — | 5063.4 | 18,850.0 | 38,178.6 | 68,603.0 |

| Grand total | 808,551.2 | 1,188,101.4 | 1,745,608.2 | 2,345,788.6 | 3,182,139.3 | |

This huge corpus of fund is managed by the following fund managers. The list of fund managers and AUM is given below in Table 2. All fund managers continued to register impressive growth in AUM. The pension sector in 2019 recorded growth of 35.65% in the AUM as compared to 2018. Being the new entrant in the pension market, Birla Sunlife Pension Management Ltd. recorded the highest growth of 285% in AUM in the year 2019 (NPS Trust annual report, 2018–2019).

| Sr. no. | PFM | 2015 | 2016 | 2017 | 2018 | 2019 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | SBI Pension Fund Pvt. Ltd. | 314,071 | 460,188 | 667,232 | 8,92,832 | 12,19,590 |

| 2 | UTI Retirement Solution Ltd. | 248,314 | 359,182 | 520,431 | 7,01,302 | 9,27,193 |

| 3 | LIC Pension Fund Ltd. | 240,101 | 355,119 | 527,093 | 6,94,832 | 9,37,077 |

| 4 | ICICI Prudential Pension Funds Management Company Ltd. | 3690 | 7011 | 14,415 | 25,603 | 51,647 |

| 5 | Kotak Mahindra Pension Fund Ltd. | 1074.744 | 1727 | 3120 | 23,255 | 34,760 |

| 6 | Reliance Capital Pension Fund Ltd. | 769.6571 | 1112 | 1690 | 5362 | 7847 |

| 7 | HDFC | 530.7745 | 3762 | 11,630 | 2310 | 2893 |

| 8 | Birla Sunlife Pension Management Ltd. | — | — | — | 294 | 1132 |

| Total | 808,552 | 1,188,102 | 1,745,610 | 23,457,90 | 31,821,39 | |

2 REVIEW OF LITERATURE

Very few studies have examined the efficiency of the pension funds using data envelopment analysis (DEA). First such study was conducted by Braberman et al. (1999) on Argentinean pension funds. They used Cobb–Douglas frontier and concluded that although regulations increased cost but did not affect the efficiency of the funds significantly. Radial models variable return to scale (VRS) and constant return to scale (CRS) were used by Barrientos and Boussofiane (2005) to assess the efficiency of Chilean pension funds during the period 1982–1999. They found variation in the average efficiency levels during the period. They also found positive relationship between market shares and efficiency scores. To assess the effect of mergers and acquisitions on the efficiency of Portuguese pension fund companies during the period 1994–2003, Barros and Garcia (2006) used BCC, constant return to scale (CRS), cross efficiency, and super efficiency measures and found high level of average technical and scale efficiencies. They also found that merger and acquisitions have positive significant relationship with the efficiency of the firms involved in it. Bikker and Dreu (2006) in their study on Netherlands' pension funds found that industry-wide pension funds were significantly more efficient than company funds and other funds. Barros et al. (2008) studied the efficiency of 10 pension funds in Argentina using stochastic frontier model and found that the mean technical efficiency was 0.86.

To assess the efficiency of Australian pension funds during the period 2005–2009, Sathye (2011) used radial production model along with the Tobit regression. He found low efficiencies in the pension funds during the study period. Using the Tobit model, he found that fund size and investment in risk-free assets positively affected the efficiency whereas “number of products offered” negatively affected the efficiency. Andreu et al. (2014) evaluated the efficiency of the Spanish pension funds using slack-based measures of DEA. They evaluated funds categorically and found Variant III the most efficient. Galagedera and Watson (2015) evaluated Australian pension funds of four categories, namely, corporate, retail, public, and industry. They found that membership and proportion to risky assets had a negative association with the fund performance but fund size had a positive association. Drazenovic et al. (2019) evaluated Croatian pension funds for the period 2015–2018 using CCR and BCC models of DEA. They found that Croatian pension funds were fairly efficient. Lin et al. (2020) evaluated investment trust corporations in Taiwan using the additive network DEA approach for the period from 2011 to 2017. They found that overall mean technical efficiency was 0.555 with an 18.3% variation in efficiency scores. The present study contributes to the literature on pension funds efficiency in several ways. First, we assess the efficiency of the Indian pension funds. Second, we explore the reasons of inefficiency and third, we explore the main drivers of efficiency.

3 OBJECTIVES

There are three main objectives of this study. The first objective is to assess the efficiency of Indian pension funds. The second objective is to find the reasons of inefficiency. Finally, the third objective is to explore the main drivers of efficiency and check whether it confirms or contrast the past findings.

4 DATA AND METHODOLOGY

Data for this study has been taken from the annual reports of the NPS trust, India for the period starting from the financial year 2014–2015 to 2018–2019. Here, financial year means a period from April 1 of the year to March 31 of the next year. Presently, there are total eight pension fund managers in the Indian pension sector, which are managing a total of 64 pension funds under 13 different fund categories. Majority of the studies on mutual fund efficiency evaluation have used mean returns as the output variable and risk (total or systematic), expenses, and minimum initial investment as input variables (Basso & Funari, 2001; Choi & Murthi, 2001; Morey & Morey, 1999; Sedzro & Sardano, 1999; Sengupta & Zohar, 2001; Sharma & Sharma, 2018). Return of funds is a conventional output in the DEA studies whereas conventional inputs are risk (standard deviation, beta) and the expense ratio (management fees, administrative expenses) (Daraio & Simar, 2006). Fund returns are annualized returns net of expenses. The standard deviation of returns shows the fund's total risk whereas the beta coefficient (systematic risk) represents the fund's volatility in compare to market return. Systematic risk cannot be reduced or removed even after diversification (Sharpe, 1966). Consistent with the previous studies, this study has used return as an output variable and standard deviation, beta, and expense ratio as the input variables. Our input and output variables for this study are as given below in Table 3.

| Financial year | SD | Beta | Expense ratio | Return | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2014–2015 | Min | 0.0353 | 0.3823 | 0.0134 | 0.0839 |

| Max | 0.1561 | 1.2322 | 0.2632 | 0.1380 | |

| Average | 0.0811 | 0.6953 | 0.2037 | 0.1063 | |

| SD | 0.0402 | 0.2580 | 0.1077 | 0.0127 | |

| 2015–2016 | Min | 0.0040 | −0.1415 | 0.0134 | 0.0412 |

| Max | 0.2553 | 0.9418 | 0.2632 | 0.1430 | |

| Average | 0.0882 | 0.2363 | 0.2161 | 0.0976 | |

| SD | 0.0580 | 0.4042 | 0.0987 | 0.0163 | |

| 2016–2017 | Min | 0.0182 | 0.4174 | 0.0134 | 0.0855 |

| Max | 0.1941 | 1.4013 | 0.2632 | 0.1660 | |

| Average | 0.0786 | 0.7050 | 0.2161 | 0.1060 | |

| SD | 0.0494 | 0.3480 | 0.0987 | 0.0141 | |

| 2017–2018 | Min | 0.0234 | −1.1193 | 0.0134 | 0.0647 |

| Max | 0.1593 | 1.5333 | 0.2632 | 0.1549 | |

| Average | 0.0726 | −0.2020 | 0.2062 | 0.0995 | |

| SD | 0.0401 | 0.7500 | 0.1057 | 0.0127 | |

| 2018–2019 | Min | 0.0033 | −0.3100 | 0.0134 | 0.0605 |

| Max | 0.1380 | 0.8140 | 0.2632 | 0.1510 | |

| Average | 0.0604 | 0.2506 | 0.2125 | 0.0963 | |

| SD | 0.0385 | 0.2535 | 0.1013 | 0.0137 | |

DEA is a linear programming-based technique for measuring the relative performance of organizational units where the presence of multiple inputs and outputs makes comparisons difficult. The DEA models include the CCR model, The VRS model, stochastic DEA, and nonparametric stochastic frontier estimation. DEA is a multifactor productivity analysis model for measuring the relative efficiency of a homogenous set of decision-making units (DMUs). For every inefficient DMU, DEA identifies a set of corresponding efficient DMUs that can be utilized as benchmarks for the improvement of performance and productivity. DEA is developed based on two scales of assumptions, namely, CRS model and VRS model.

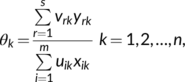

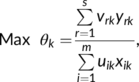

Charnes et al. (1978) proposed a model, which had an input orientation and assumed CRS. Subsequent papers have considered alternative sets of assumptions, such as Banker et al. (1984) who proposed a VRS model. The following discussion of DEA begins with a description of the input-orientated CRS model that was the first to be widely applied. This study attempts to measure the technical efficiency using the input-oriented BCC model so it calculates the VRS (BCC) scores for the years from 2015 to 2019.

4.1 CCR and BCC input-oriented models

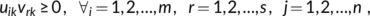

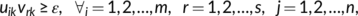

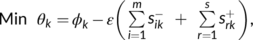

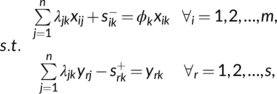

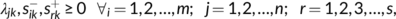

be the amount of the ith input used by the kth pension fund,

be the amount of the ith input used by the kth pension fund,  be the amount of rth output produced by the kth pension fund,

be the amount of rth output produced by the kth pension fund,  be the weight given to the ith input of the kth pension fund,

be the weight given to the ith input of the kth pension fund,  be the weight given to the rth output of the kth pension fund. Then, the efficiency of the kth pension fund can be represented as,

be the weight given to the rth output of the kth pension fund. Then, the efficiency of the kth pension fund can be represented as,

is unrestricted in sign,

is unrestricted in sign,  is non-Archimedean constant,

is non-Archimedean constant,  is the dual variable corresponding to the jth constraint and is known as intensity variable,

is the dual variable corresponding to the jth constraint and is known as intensity variable,  is the slack in the ith input of the kth pension fund, and

is the slack in the ith input of the kth pension fund, and  is the slack in the rth output of the kth pension fund. On imposing the condition

is the slack in the rth output of the kth pension fund. On imposing the condition  in the above model, it becomes the input-oriented BCC model.

in the above model, it becomes the input-oriented BCC model.Different frontier models have been used for the evaluation of DMUs. The parametric and nonparametric approach has been used for comparing performance by the researchers. Mogha et al. (2014, 2016) evaluated the technical efficiency of private and public sector hospitals of India using DEA-CCR and BCC output-oriented models. Mogha (2020) evaluated the performance of academic departments of selected private institutions in India using DEA- based dual CCR model.

The fundamental property of DEA is that it is independent of the units of the input and output variables, that is, unit invariant (Russell, 1988). According to Pastor and Lovell (1995), the BCC-DEA model is scale invariant in input or output variables but not in both. Hollingsworth and Smith (2003) found that the nature of available data necessitates the use of ratios, as ratios represent more accurately the production function rather than absolute numbers in DEA. They recommended the application of the BCC-DEA model when ratios are used as input and output variables. So, because of the nature of available data, this study has used the radial (BCC-DEA model, Banker et al., 1984) model of DEA. Efficiency estimates are calculated using deaR software, R version 3.6.

4.2 Specification of the regression model

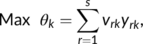

The technical efficiency (VRS) scores of the pension funds estimated by DEA are used as dependent variable. Since efficiency scores lie between 0 and 1, therefore Tobit regression model is suitable for this study. The Tobit regression model has also been used in similar studies by Barrientos and Boussofiane (2005), Sathye (2011), and Galagedera and Watson (2015) Independent variables for this study includes AUM, age of the pension funds, sector (government or private) and type of fund manager (public sector or private). These independent variables have also been used by Barrientos and Boussofiane (2005), Sathye (2011), and Galagedera and Watson (2015) in their respective studies. The Tobit regression model estimated is presented below;

Here, m is the pension fund, n is time, TE is efficiency scores under variable returns of scale, AUM is natural log of asset under management of pension funds, age of funds (AOF) is 1 if more than or equal to 5 years old otherwise 0, Sector is 1 if govt. sector otherwise 0, TOFM (Type of fund manager) is 1 if public sector's fund manager otherwise 0 and  is error term, and α, β1, β2, β3, and β4 are parameters.

is error term, and α, β1, β2, β3, and β4 are parameters.

5 RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

Using the stated inputs and outputs, we have received results for all the pension funds for the financial year 2014–2015. As is clear from Table 4, Column (3), total 16 of the 42 pension funds operated efficiently in the year 2014–2015. The result shows that the average efficiency score for pension funds was 0.8062 and there was significant variation in the efficiency scores of pension funds as the standard deviation was 21.16%. The highest efficiency score was 1, which was achieved by 16 pension funds while the lowest efficiency score was 0.4104 experienced by UTI Retirement Solution Ltd. E2 fund. LIC Pension Fund Ltd. C1, Birla Sunlife C2, HDFC C2, HDFC E1, LIC Pension Fund Ltd. E1, HDFC E2, LIC Pension Fund Ltd. E2, HDFC G1, LIC Pension Fund Ltd. G1, HDFC G2, LIC Pension Fund Ltd. G2, LIC Pension Fund Ltd. APY, SBI Pension Fund Ltd. APY, UTI Retirement Solution Ltd. APY, HDFC A1, ICICI Prudential Pension Funds A1, Kotak Mahindra Pension Fund Ltd. A1, LIC Pension Fund Ltd. A1, Reliance Capital Pension Fund Ltd. A1, SBI Pension Fund Pvt. Ltd. A1 and UTI Retirement Solution Ltd. A1 were not in business in the year 2014–2015.

| Sr. no. | Pension fund | 2014–2015 | 2015–2016 | 2016–2017 | 2017–2018 | 2018–2019 | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Score | Rank | Score | Rank | Score | Rank | Score | Rank | Score | Rank | ||

| 1 | LIC Pension Fund Ltd. CG | 1.0000 | 1 | 1.0000 | 1 | 1.0000 | 1 | 1.0000 | 1 | 1.0000 | 1 |

| 2 | SBI Pension Fund Pvt. Ltd. CG | 1.0000 | 1 | 1.0000 | 1 | 1.0000 | 1 | 1.0000 | 1 | 1.0000 | 1 |

| 3 | UTI Retirement Solution Ltd. CG | 1.0000 | 1 | 1.0000 | 1 | 1.0000 | 1 | 1.0000 | 1 | 1.0000 | 1 |

| 4 | LIC Pension Fund Ltd. SG | 1.0000 | 1 | 1.0000 | 1 | 1.0000 | 1 | 1.0000 | 1 | 1.0000 | 1 |

| 5 | SBI Pension Fund Pvt. Ltd. SG | 1.0000 | 1 | 1.0000 | 1 | 1.0000 | 1 | 1.0000 | 1 | 1.0000 | 1 |

| 6 | UTI Retirement Solution Ltd. SG | 1.0000 | 1 | 1.0000 | 1 | 1.0000 | 1 | 1.0000 | 1 | 1.0000 | 1 |

| 7 | HDFC C1 | — | — | 0.9623 | 2 | 1.0000 | 1 | 0.9296 | 4 | 0.9172 | 7 |

| 8 | ICICI Prudential Pension Funds C1 | 0.9950 | 3 | 1.0000 | 1 | 0.9086 | 16 | 1.0000 | 1 | 1.0000 | 1 |

| 9 | Kotak Mahindra Pension Fund Ltd. C1 | 1.0000 | 1 | 0.9356 | 4 | 0.9144 | 15 | 0.9796 | 2 | 1.0000 | 1 |

| 10 | LIC Pension Fund Ltd. C1 | — | — | 1.0000 | 1 | 1.0000 | 1 | 1.0000 | 1 | 0.8682 | 10 |

| 11 | Reliance Capital Pension Fund Ltd. C1 | 0.9966 | 2 | 0.8039 | 6 | 0.9551 | 8 | 0.8440 | 8 | 0.8107 | 17 |

| 12 | SBI Pension Fund Pvt. Ltd. C1 | 1.0000 | 1 | 0.8964 | 5 | 0.9521 | 9 | 0.9592 | 3 | 0.9684 | 4 |

| 13 | UTI Retirement Solution Ltd. C1 | 1.0000 | 1 | 0.7459 | 10 | 0.9582 | 6 | 1.0000 | 1 | 0.8328 | 14 |

| 14 | Birla Sunlife C2 | — | — | — | — | — | — | 1.0000 | 1 | 0.6890 | 19 |

| 15 | HDFC C2 | — | — | 1.0000 | 1 | 1.0000 | 1 | 1.0000 | 1 | 0.8945 | 8 |

| 16 | ICICI Prudential Pension Funds C2 | 1.0000 | 1 | 0.9514 | 3 | 0.9223 | 12 | 1.0000 | 1 | 0.9668 | 5 |

| 17 | Kotak Mahindra Pension Fund Ltd. C2 | 0.9856 | 4 | 0.6848 | 13 | 0.9028 | 17 | 0.8276 | 10 | 0.8441 | 12 |

| 18 | Reliance Capital Pension Fund Ltd. C2 | 1.0000 | 1 | 0.7342 | 11 | 0.9567 | 7 | 0.8520 | 7 | 0.8418 | 13 |

| 19 | SBI Pension Fund Pvt. Ltd. C2 | 0.9649 | 6 | 0.7895 | 7 | 0.9861 | 4 | 0.8581 | 6 | 0.8455 | 11 |

| 20 | UTI Retirement Solution Ltd. C2 | 0.9804 | 5 | 0.6849 | 12 | 0.9984 | 2 | 0.9000 | 5 | 0.8200 | 15 |

| 21 | HDFC E1 | — | — | 1.0000 | 1 | 1.0000 | 1 | 1.0000 | 1 | 1.0000 | 1 |

| 22 | ICICI Prudential Pension Funds E1 | 1.0000 | 1 | 0.3123 | 27 | 0.4257 | 28 | 0.5388 | 25 | 0.5759 | 23 |

| 23 | Kotak Mahindra Pension Fund Ltd. E1 | 0.4997 | 21 | 0.2561 | 32 | 0.3753 | 39 | 0.3922 | 27 | 0.4322 | 38 |

| 24 | LIC Pension Fund Ltd. E1 | — | — | 0.2293 | 37 | 0.6885 | 27 | 0.6221 | 16 | 0.8175 | 16 |

| 25 | Reliance Capital Pension Fund Ltd. E1 | 0.6517 | 20 | 0.2544 | 33 | 0.4221 | 30 | 0.3666 | 28 | 0.4135 | 39 |

| 26 | SBI Pension Fund Pvt. Ltd. E1 | 0.4558 | 24 | 0.2642 | 29 | 0.3844 | 35 | 0.3056 | 30 | 0.3261 | 41 |

| 27 | UTI Retirement Solution Ltd. E1 | 0.7856 | 8 | 0.2739 | 28 | 0.3777 | 38 | 0.5139 | 26 | 0.5505 | 26 |

| 28 | HDFC E2 | — | — | 0.1947 | 39 | 0.4127 | 31 | 0.5577 | 23 | 0.6462 | 20 |

| 29 | ICICI Prudential Pension Funds E2 | 0.4496 | 25 | 0.2512 | 35 | 0.3946 | 33 | 0.2904 | 34 | 0.2853 | 46 |

| 30 | Kotak Mahindra Pension Fund Ltd. E2 | 0.4649 | 22 | 0.2593 | 31 | 0.3818 | 36 | 0.3156 | 29 | 0.3336 | 40 |

| 31 | LIC Pension Fund Ltd. E2 | — | — | 0.2012 | 38 | 0.4013 | 32 | 0.2933 | 33 | 0.2894 | 45 |

| 32 | Reliance Capital Pension Fund Ltd. E2 | 0.4603 | 23 | 0.2542 | 34 | 0.4246 | 29 | 0.2936 | 32 | 0.2904 | 44 |

| 33 | SBI Pension Fund Pvt. Ltd. E2 | 0.4490 | 26 | 0.2630 | 30 | 0.3900 | 34 | 0.3028 | 31 | 0.2964 | 43 |

| 34 | UTI Retirement Solution Ltd. E2 | 0.4104 | 27 | 0.2456 | 36 | 0.3795 | 37 | 0.2863 | 35 | 0.3127 | 42 |

| 35 | LIC Pension Fund Ltd. CCG | 0.8556 | 7 | 0.4541 | 19 | 0.7405 | 26 | 0.5726 | 20 | 0.5742 | 24 |

| 36 | SBI Pension Fund Pvt. Ltd. CCG | 0.7088 | 9 | 0.4115 | 26 | 0.7872 | 25 | 0.5409 | 24 | 0.5475 | 27 |

| 37 | HDFC G1 | — | — | 0.5071 | 14 | 0.9151 | 14 | 0.7764 | 11 | 0.5533 | 25 |

| 38 | ICICI Prudential Pension Funds G1 | 0.6562 | 19 | 0.4401 | 22 | 0.9218 | 13 | 0.5856 | 18 | 0.4790 | 33 |

| 39 | Kotak Mahindra Pension Fund Ltd. G1 | 0.7031 | 10 | 0.4660 | 17 | 0.8653 | 24 | 0.7615 | 12 | 0.4718 | 35 |

| 40 | LIC Pension Fund Ltd. G1 | — | — | 0.7464 | 9 | 0.8854 | 21 | 0.8343 | 9 | 0.8081 | 18 |

| 41 | Reliance Capital Pension Fund Ltd. G1 | 0.6768 | 14 | 0.4409 | 21 | 0.8809 | 22 | 0.5902 | 17 | 0.4652 | 36 |

| 42 | SBI Pension Fund Pvt. Ltd. G1 | 0.6624 | 17 | 0.4542 | 18 | 0.8883 | 20 | 0.5648 | 21 | 0.5355 | 29 |

| 43 | UTI Retirement Solution Ltd. G1 | 0.6793 | 13 | 0.4305 | 24 | 0.9969 | 3 | 1.0000 | 1 | 0.4598 | 37 |

| 44 | HDFC G2 | — | — | 0.7504 | 8 | 0.9679 | 5 | 1.0000 | 1 | 0.6380 | 21 |

| 45 | ICICI Prudential Pension Funds G2 | 0.6582 | 18 | 0.4325 | 23 | 0.9271 | 11 | 0.5732 | 19 | 0.4798 | 32 |

| 46 | Kotak Mahindra Pension Fund Ltd. G2 | 0.6912 | 11 | 0.4697 | 16 | 0.8920 | 19 | 0.7443 | 14 | 0.4779 | 34 |

| 47 | LIC Pension Fund Ltd. G2 | — | — | 1.0000 | 1 | 1.0000 | 1 | 1.0000 | 1 | 0.9396 | 6 |

| 48 | Reliance Capital Pension Fund Ltd. G2 | 0.6686 | 16 | 0.4410 | 20 | 0.8983 | 18 | 0.5604 | 22 | 0.4949 | 30 |

| 49 | SBI Pension Fund Pvt. Ltd. G2 | 0.6712 | 15 | 0.4907 | 15 | 0.8749 | 23 | 0.7352 | 15 | 0.5469 | 28 |

| 50 | UTI Retirement Solution Ltd. G2 | 0.6802 | 12 | 0.4223 | 25 | 0.9521 | 10 | 0.7565 | 13 | 0.4876 | 31 |

| 51 | Kotak Mahindra Pension Fund Ltd. NPS lite | 1.0000 | 1 | 1.0000 | 1 | 1.0000 | 1 | 1.0000 | 1 | 1.0000 | 1 |

| 52 | LIC Pension Fund Ltd. NPS lite | 1.0000 | 1 | 1.0000 | 1 | 1.0000 | 1 | 1.0000 | 1 | 1.0000 | 1 |

| 53 | SBI Pension Fund Pvt. Ltd. NPS lite | 1.0000 | 1 | 1.0000 | 1 | 1.0000 | 1 | 1.0000 | 1 | 1.0000 | 1 |

| 54 | UTI Retirement Solution Ltd. NPS lite | 1.0000 | 1 | 1.0000 | 1 | 1.0000 | 1 | 1.0000 | 1 | 1.0000 | 1 |

| 55 | LIC Pension Fund Ltd. APY | — | — | — | — | — | — | 1.0000 | 1 | 1.0000 | 1 |

| 56 | SBI Pension Fund Pvt. Ltd. APY | — | — | — | — | — | — | 1.0000 | 1 | 1.0000 | 1 |

| 57 | UTI Retirement Solution Ltd. APY | — | — | — | — | — | — | 1.0000 | 1 | 1.0000 | 1 |

| 58 | HDFC A1 | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | 1.0000 | 1 |

| 59 | ICICI Prudential Pension Funds A1 | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | 1.0000 | 1 |

| 60 | Kotak Mahindra Pension Fund Ltd. A1 | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | 1.0000 | 1 |

| 61 | LIC Pension Fund Ltd. A1 | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | 0.6147 | 22 |

| 62 | Reliance Capital Pension Fund Ltd. A1 | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | 0.9960 | 2 |

| 63 | SBI Pension Fund Pvt. Ltd. A1 | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | 0.8784 | 9 |

| 64 | UTI Retirement Solution Ltd. A1 | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | 0.9843 | 3 |

| Average | 0.8062 | — | 0.6378 | — | 0.8171 | — | 0.7689 | — | 0.7391 | — | |

| SD | 0.2116 | — | 0.3054 | — | 0.2384 | — | 0.2571 | — | 0.2541 | — | |

| Minimum | 0.4104 | — | 0.1947 | — | 0.3753 | — | 0.2863 | — | 0.2853 | — | |

| Maximum | 1.0000 | — | 1.0000 | — | 1.0000 | — | 1.0000 | — | 1.0000 | — | |

| Number of efficient funds | 16 | — | 15 | — | 15 | — | 23 | — | 19 | — | |

| Number of inefficient funds | 26 | — | 38 | — | 38 | — | 34 | — | 45 | — | |

Column (5) of Table 4 shows that in the financial year 2015–2016, the number of pension funds increased from 42 to 53 but the number of efficient funds decreased to 15. Six previously efficient funds, namely, ICICI Prudential Pension Funds E1, SBI Pension Fund Pvt. Ltd. C1, UTI Retirement Solution Ltd. C1, Kotak Mahindra Pension Fund Ltd. C1, ICICI Prudential Pension Funds C2, and Reliance Capital Pension Fund Ltd. C2 could not remain efficient in the year 2015–2016. Six new funds, namely, HDFC E1, LIC Pension Fund Ltd. C1, ICICI Prudential Pension Fund C1, HDFC C2, and LIC Pension Fund Ltd. G2 joined the efficient frontier. The lowest efficiency of 0.1947 was experienced by the pension fund HDFC E2. The average efficiency of pension funds decreased to 0.6378 and high variation of 30.54% was observed in the efficiency scores of the pension funds. Birla Sunlife C2, LIC Pension Fund Ltd. APY, SBI Pension Fund Ltd. APY, UTI Retirement Solution Ltd. APY, HDFC A1, ICICI Prudential Pension Funds A1, Kotak Mahindra Pension Fund Ltd. A1, LIC Pension Fund Ltd. A1, Reliance Capital Pension Fund Ltd. A1, SBI Pension Fund Pvt. Ltd. A1 and UTI Retirement Solution Ltd. A1 were not in business in the year 2015–2016.

It is clear from Column (7) of Table 4 that number of efficient funds remained the same, that is, 15 in the financial year 2016–2017 as was in the previous year. ICICI Prudential Pension Fund C1 converted into the inefficient fund while HDFC C1 fund converted into an efficient one. Rest all efficient pension funds were the same as in the previous year. The average efficiency of the pension funds increased to 0.8171 in the year 2016–2017. This was the highest average efficiency score achieved by the pension funds during our study period. Efficiency variation of 23.84% was observed in Pension funds during this year. Minimum efficiency of 0.3753 was observed in Kotak Mahindra Pension Fund Ltd. Birla Sunlife C2, LIC Pension Fund Ltd. APY, SBI Pension Fund Ltd. APY, UTI Retirement Solution Ltd. APY, HDFC A1, ICICI Prudential Pension Funds A1, Kotak Mahindra Pension Fund Ltd. A1, LIC Pension Fund Ltd. A1, Reliance Capital Pension Fund Ltd. A1, SBI Pension Fund Pvt. Ltd. A1 and UTI Retirement Solution Ltd. A1 were not in business in the year 2016–2017.

As is evident from Column (9) of Table 4, the number of total pension funds increased from 53 to 57 in the financial year 2017–2018. The number of efficient funds increased from 15 to 23 in this year. Besides the old ones, the new pension funds that entered the efficient frontier include; UTI Retirement Solution Ltd. C1, ICICI Prudential Pension Funds C1, ICICI Prudential Pension Funds C2, Birla Sunlife C2, UTI Retirement Solution Ltd. G1, HDFC G2, SBI Pension Fund Pvt. Ltd. APY, UTI Retirement Solution Ltd. APY and LIC Pension Fund Ltd. APY whereas HDFC C1 fund left the efficient frontier. The average efficiency of the pension funds decreased to 0.7689 in 2017–2018 as compared to the previous year. A significant variation of 25.71% was observed in the efficiency performance of the pension funds during this year. The lowest efficiency of 0.2863 was observed in the UTI Retirement Solution Ltd. E2 fund. HDFC A1, ICICI Prudential Pension Funds A1, Kotak Mahindra Pension Fund Ltd. A1, LIC Pension Fund Ltd. A1, Reliance Capital Pension Fund Ltd. A1, SBI Pension Fund Pvt. Ltd. A1 and UTI Retirement Solution Ltd. A1 were not in business in the year 2017–2018.

It is evident from Column (11) of Table 4 that total number of pension funds increased to 64 in the financial year 2018–2019, which was the highest number during our study period. The number of efficient funds decreased to 19 in the year 2018–2019. Efficient funds like UTI Retirement Solution Ltd. C1, LIC Pension Fund Ltd. C1, ICICI Prudential Pension Funds C2, HDFC C2, Birla Sunlife C2, UTI Retirement Solution Ltd. G1, LIC Pension Fund Ltd. G2 and HDFC G2 converted into inefficient funds during this year whereas only one fund “Kotak Mahindra Pension Fund Ltd. C1” converted into efficient fund. Average efficiency slightly reduced to 0.7391 in the year 2018–2019. A significant variation of 25.41% was observed in the efficiency levels of the pension funds. The lowest efficiency of 0.2853 was observed in ICICI Prudential Pension Fund E2.

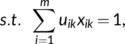

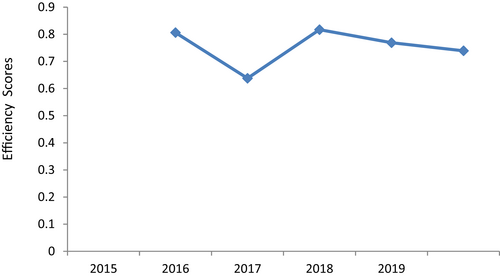

Figure 1 shows that the average efficiency score of Indian Pension Funds drastically reduces in the year 2016 and recoups by 2017 then again decreases in the years 2018 and 2019.

Source: Author's calculation

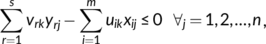

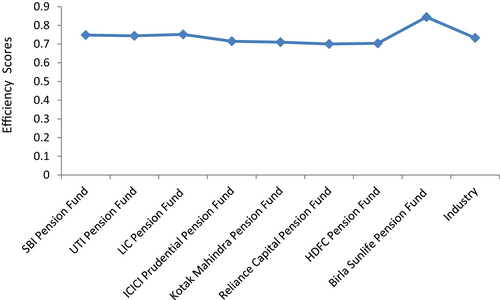

Figure 2 shows approximate uniformity in the efficiency performance of all the pension fund managers except Birla Sunlife. Birla Sunlife achieved higher average efficiency score because it offered only one pension scheme during the study period.

Source: Author's calculation

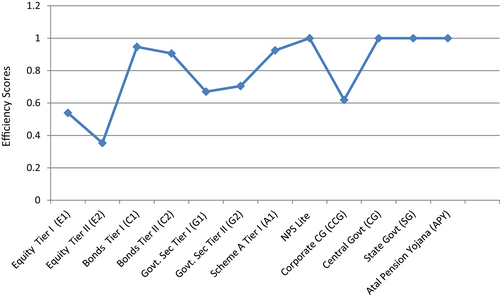

Figure 3 shows variation in the average efficiency performance of different pension schemes. The minimum efficiency was achieved by the Equity Tier II scheme whereas the highest efficiency was achieved by NPS lite, CG, SG, and APY schemes. During our study period, the average efficiency of the Indian pension sector has been found 0.7538 and this sector experienced overall stability in the efficiency performance, about 40% of pension funds operated efficiently. Drazenovic et al. (2019) in their study on Croatian pension funds for the period 2015–2019 found the average efficiency of 0.987. Whereas, Sathye (2011) in his study on Australian pension funds found that the pensions had low efficiencies over the period considered (2005–2009), with mean technical efficiency of 40%, and only 15%–20% of DMUs being technically efficient.

Source: Author's calculation

Table 5 shows the relative mean slacks (Murthi et al., 1997). It is a ratio of absolute average slack of an input all over funds to the average value of input all over funds. Relative mean slacks identify the marginal effect of inputs on return that are used inefficiently by fund managers. It is evident from the above table that relative mean slacks in the year 2017–2018 were the least, which brought 40% of the pension funds to the efficient frontier. That was the highest number during our study period. In the year 2016–2017 and 2018–2019, the relative average slack in expense ratio was zero; however, larger slacks were observed in the standard deviation. Similarly, in the year 2015–2016, the relative average slack in expense ratio was zero; however, larger slack was observed in the beta. In the year, 2014–2015, relative mean slack was observed in the expense ratio but 38% of the total pension funds were found efficient. This was higher than in the years 2015–2016 (28%), 2016–2017 (28%), and 2018–2019 (30%) in which zero relative mean slack was observed in the expense ratio. This confirms to “mean-variance efficiency hypothesis” (Sengupta, 2003; Sengupta & Zohar, 2001). As per this hypothesis, inefficiency of the funds is because of the associated risk and not the associated expenses.

| Year | Standard deviation | Beta | Expense ratio | % age of efficient funds |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2014–2015 | 0.1523 | 0.1651 | 0.3630 | 38 |

| 2015–2016 | 0.0119 | 0.4237 | 0 | 28 |

| 2016–2017 | 0.1990 | 0.0354 | 0 | 28 |

| 2017–2018 | 0.0441 | −1.8903 | 0 | 40 |

| 2018–2019 | 0.4896 | 0.3140 | 0 | 30 |

Tobit regression is applied using the AER software, R version 3.6. Table 6 reports the results obtained by the Tobit regression. The coefficients are interpreted to analyze the relationship between efficiency changes and independent variables. The results reveal that two of the four explanatory variables are statistically significant. The results given in Table 6 shows that the estimated coefficient for the AUM of the pension funds is positive and statistically significant at 5% level of significance. This indicates that large-sized pension funds perform better and positively affect the efficiency. Barrientos and Boussofiane (2005), Sathye (2011), and Galagedera and Watson (2015) also found that fund size positively affect the performance of the pension funds. The estimated coefficient for the sector type of the pension funds is also positive and statistically significant. This indicates that pension funds for CG and SG employees perform better than the private sector pension funds. Galagedera and Watson (2015) also found that public sector funds perform better than retail and industry funds. All other variables are not found to have any statistically significant effect on the efficiency performance of the pension funds.

| Variables | Coefficients | Std. error | z-value | t-value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Constant | 0.763550 | 0.042212 | 18.089 | 17.920 |

| AUM | 0.014779 | 0.007446 | 1.985 | 1.966 |

| Age of Fund | −0.138422 | 0.035947 | −3.851 | −3.815 |

| Sector type | 0.228420 | 0.062479 | 3.656 | 3.622 |

| Fund manager type | −0.002542 | 0.032686 | −0.078 | −0.077 |

| R2 | — | — | — | 0.1691 |

| Wald statistic | 54.73 | — | — |

- Abbreviations: AUM, asset under management; VRS, variable return to scale.

6 CONCLUSION

The study has estimated the efficiency of Indian pension funds for the years 2015–2019. BCC model of DEA was used to estimate efficiency estimates. This study has found that the average efficiency of the Indian pension sector was 0.7538 and this sector experienced overall stability in the efficiency performance with only a slight variation of 7.18% in the efficiency scores during the study period. Indian pension sector achieved the maximum efficiency of 0.8171 in the financial year 2016–2017 and minimum efficiency of 0.6378 in the financial year 2015–2016. Overall, the efficiency of Indian pension funds is found to be high. Whereas, pension funds of some countries like Chile and Australia had low-efficiency scores. The pension funds of other countries like Croatia had higher efficiency scores as compared to India. Indian pension sector has expanded during our study period. The numbers of pension funds increased from 42 in the year 2014–2015 to 64 in the year 2018–2019. The number of efficient pension funds increased from 16 to 19 over the years which were 40% of the total funds. Whereas, only 15%–20% of Australian pension funds were found efficient by Sathye (2011) during the period 2005–2009. About 62% of the pension funds were inefficient in the financial year 2014–2015 and this share increased to 70% in the financial year 2018–2019. SBI Pension Fund Pvt. Ltd. CG, UTI Retirement Solution Ltd. CG, LIC Pension Fund Ltd. CG, SBI Pension Fund Pvt. Ltd. SG, UTI Retirement Solution Ltd. SG, LIC Pension Fund Ltd. SG, SBI Pension Fund Pvt. Ltd. NPS lite, UTI Retirement Solution Ltd. NPS lite, LIC Pension Fund Ltd. NPS lite, and Kotak Mahindra Pension Fund Ltd. NPS lite were found efficient throughout the study period.

Then relative mean slacks were calculated to identify the marginal effect of inputs on return. The minimum slack was found in the input “expense ratio.” This shows that risk associated with investments is the cause of inefficiency in the Indian pension funds. This confirms to “mean-variance efficiency hypothesis” (Sengupta, 2003; Sengupta & Zohar, 2001). The efficiency scores were then related to explanatory variables like fund size (AUM), sector, types of fund manager, and age of fund. The relationship was examined using the Tobit regression model. It was found that fund size of pension funds and government sector pension funds are found to have positively associated with technical efficiency. This confirms to findings of Barrientos and Boussofiane (2005), Sathye (2011), and Galagedera and Watson (2015). Whereas, type of fund manager and AOF were found to have nonsignificant association with efficiency of the pension fund.

7 IMPLICATIONS AND LIMITATIONS OF THE STUDY

There are many small pension funds operating in the Indian pension sector. Our study like Sathye (2011) also indicates that economies of scale can be achieved through rationalization of the sector. It is recommended that mergers & acquisitions be encouraged to enhance the efficiency of this sector, which would ultimately benefit the pension subscribers. This is the first study that has assessed the efficiency of the India pension funds and explored the drivers of efficiency. This study will be helpful for the Indian pension fund subscribers in taking informed decisions before making any investment. Our study provides information to the inefficient pension funds on their shortcomings in every aspect of input excess and output shortfall. The pension funds that scored low in efficiency score should seal the leakages regarding commission as well as distribution channel to reduce/stop adverse performance. Based on this understanding, managers can formulate and implement to convert the fund into the efficient one. This study may also be useful for the policymakers, that is, PFRDA of India in formulating future policies as an awareness of the determinants of cost efficiency may assist in formulating policies related to distribution channels, the commission paid, and working of channel members so that sustainability and efficiency of pension fund managers are secured. Due to unavailability of the required data, efficiency performance of the pension fund managers could not be analyzed.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The author is grateful to the anonymous referees of the journal for their extremely useful suggestions to improve the quality of the article.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST

The authors declare no potential conflict of interest.

Biography

Shoaib Alam Siddiqui is an Assistant Professor at the Joseph School of Business Studies, Sam Higginbottom University of Agriculture, Technology and Sciences, Allahabad, India. He holds his Ph.D. in Business Studies. His research interests include Financial Services, Health Economics and Applied Econometrics. He does research on efficiency, productivity, market structure and development economics with special focus on life insurance, health insurance and pension. He has published in various refereed journals such as Managerial and Decision Economics, Global Business Review, Indian Journal of Economics and Development, The Indian Journal of Commerce and Journal of New Business Ventures. He has contributed various chapters in the edited books. He has over 20 years of corporate-academia experience and worked with LIC of India, TATA-AIG Life Insurance Company Limited and Reliance Life Insurance Company Limited in the past.

Open Research

DATA AVAILABILITY STATEMENT

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.