Psychological and environmental empirics of crimes in Pakistan

Abstract

Literature provides rich evidence of the role of economic development, environmental quality, and psychological stress' prevalence on the deployment of human efforts in criminal activities. This study explores the role of HDI, CO2, and Prevalence of Depression against total, violent, and nonviolent crimes in Pakistan between 1990 and 2017. Analysis based on ARDL bounds testing model which proposes that human development, environment quality, and sound mind leads to a decrease in the involvement in criminal activities. The intensity of effects is different for total, violent, and nonviolent crime rates. Government should focus on development expenditures coupled with improving the quality of the environment and mind.

1 INTRODUCTION

A crime, is a voluntary act prohibited by the law permanently or for a certain time period to safeguard the public and is punishable by the government (Marshall & Clark, 1952). Crime is often used as an indicator of the overall health and strength of the morality of the community. More precisely, economists are concerned with public policies (i.e., criminal justice and other economic health factors) that influence the incidence of crime. Through an economic lens, anotable study of crime conducted by Nobel Prize winning economist (Becker, 1968), which discussed the time allocation in illegal activities. According to Islamic economics, to kill an innocent soul is equivalent to killing whole mankind (Al-Quran, 5:32), which indicates the illegality of crimes.

The study of crime is a multi-dimensional practice. A number of studies in criminology, sociology, psychology, law, and economics have attempted to identify the socio-economic determinants (unemployment, education, poverty, etc.) and demographic determinants (urbanization, population density) of crime globally.

The customary determinants - identified as unemployment by Papps and Winkelmann (2000), education by Coomer (2003), urbanization by Gillani et al. (2009), income inequality by Baharom and Habibullah (2009), Habibullah and Baharom (2009), and Cobham (2014) are the causes of crime, whereas education is the most influential determinant which is affecting individuals' decisions to commit crimes (Anwar et al., 2015; Asghar et al., 2016). Dynamic models have also been developed and used in the economics of crime which sanctioned the combination of high households consumption and crime. Trogdon (2006), Altindag (2012), and Groenqvist (2011) have shown the significant impact of inflation on crime. Although, previously, studies lacked in exploring the determinants as depression and environmental quality as possible determinants to crime.

Ongoing criminal behavior started with the history of mankind and apprehended the interest of every society. Adam Smith, the father of economics, mentioned in his book “The Wealth of Nations (1776)” about the accretion of wealth by people, similarly he talked about the inspiration to commit crime and the demand to secure people from crime when they are collecting wealth. Crime, is largely considered as the divergent behavior of a person against the spirit of the law. It can be caused by several factors (i.e., mental illness, social tensions, economic disturbance etc.). In Regea et al. (2009) view crime is also endorsed due to mental sickness, frustration and anger. Criminal activities hinder the social, physical, psychological evolution and economic growth of a country (Dutta & Husain, 2009).

The economics of criminology, primarily based on Becker's (1968) notion, which reflects crime as a type of work, as it is time taking (alongside cost of the probability of decrease in wage, in future employment, imprisonment, physical torture, penalties, and mental guilt of criminal activity) and yields economic benefits. A person chooses among employment and crime at a specified time to generate income. These (employment and crime) are observed as substitutes of income generation, which cannot be combined (Ehrlich, 1973; Freeman & Rodgers III, 1999). Becker (1968), who pioneered the criminal model, emphasizes “some people become criminals because of the financial and other rewards from crime as compare to legal work,”, he further adds that it “compels the likelihood of apprehension and persuasion, and the severity of punishment.” His article has changed the ideology about criminal behavior. He claimed that criminals and crime enforcement agencies are economic agents, as directing the nitty-gritty of modern crime and economic discipline in his article. In empirical research, Becker's study (1968) opened the door to the researchers whose main purpose was to study the socio-economic determinants of crime.

In South Asian countries as in Pakistan, most of the population is below the national poverty line (Aurangzeb, 2012). In these countries, education negatively impacts criminal activities (Jalil & Iqbal, 2010). As education is the source for raise in earnings through legal means, it can reduce crime. According to Buonanno and Leonida (2005), education reduces crime in two potential ways. Lochner (2004) states the first way that primarily, good education raises the opportunity cost of crimes, since committing crime needs time that cannot be used in other productive activities so a high earning individual will think twice before involving in criminal activities. Second, when a criminal is in custody, there is a wastage of time (Roncek, 1993).

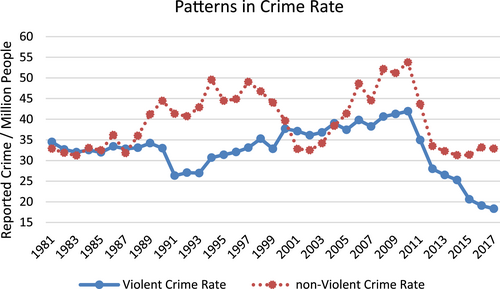

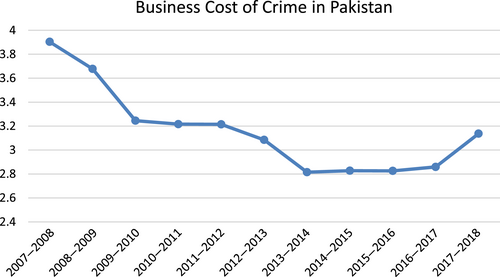

Figure 1, reports the intensity of crime in Pakistan. Here we can see that the violent and nonviolent crime rates were similar, but in the late 1980s, there came a disjoint between violent and nonviolent crimes. Illegal activity surely does impart some costs on the business and society. In case of society, the cost is surely seen in a deterioration of the moral values, interpersonal relationships and social peace (i.e., the intangibles most often). For the cost of crime and violence on business, Global Competitiveness Index by World Economic Forum provides an index. Hence, Figure 2, based on this index, reports the slightly decreasing trend of this index, representing the gradual increase in the business costs. Crime is an ample source of distress and insecurity in society. Crime, in effect, is an act prohibited by law, it augments the sensation of insecurity and fear even to those who have not been a victim. This activity creates adverse effects on well-being. This study will primarily focus on the possible factors that affect violent and nonviolent crimes in Pakistan.

source: Ministry of Interior Pakistan

)

source: World economic forum

)1.1 Objective of the study

- Does the prevalence of depression lead to violent or nonviolent crimes in Pakistan?

- Does the environment quality reduce the violent or nonviolent crimes in Pakistan?

The study is organized as following: First, the introduction, followed by Section 2 of literature review which provides insights from literature. Sections 3 and 4 provides knowledge of the methodology and the research findings respectively. The end follows Section 5 concludes the study.

2 LITERATURE REVIEW

Literature comprises the study of violent crimes, nonviolent crimes and overall crimes in developing as well as in developed nations, whereas emphasizing more on the empirical studies done on Pakistan - a developing nation. The study of crime is not restricted merely to one field; and the links between crime and various socio-economic and demographic variables have been studied from various angles. Resultantly, several theories have been developed to explain these relationships. Merton's strain theory (1938), Shaw and McKay's (1942) view about social disorganization theory, and Becker's (1968) economic theory of crime are three influential ecological theories of crime. Strain theory suggests that individuals feel more frustrated when placed near those who are more successful; as inequality increases, those on the lower end of the income distribution are more likely to channel their anger and resentment into crime. Social disorganization theory argues that as the communities become less able to regulate its members so crime increases. Factors that contribute to this community weakening include poverty, racial heterogeneity, less residential stability, and family instability (first three factors are noted by Shaw and McKay (1942), while the last one family instability was first noted as a possible factor by Kornhauser (1978).

The science of criminology is based on Becker's (1968) perception who revealed crime as a type of time taking act (besides the cost of probability of wage decline in future employment, physical torture, imprisonment, penalties, and mental guilt of criminal acts of criminals) and an economic growth. People choose between crime and employment to meet their needs. Both, crime and employment, are apparently considered substitutes for income generation that cannot be combined (Ehrlich, 1973).

Coomer (2003) has explored the impact of several economic factors like poverty, income, education and inflation on crime. The results suggest that poverty and inflation have a positive impact on the crime rate. Moreover, the relationship between education and crime was also found positive. Papps and Winkelmann (2000) conducted an empirical study to investigate the relationship between crime and unemployment to categorize crime rates in New Zealand from 1984 to 1996. Data on country level and time loop along with random effect and fixed effect models were used. Their findings indicate that there is a positive impact of unemployment on financial and violent crimes.

Gillani et al. (2009) empirically analyzed the relationship between poverty, unemployment inflation and crime in Pakistan using the data for the period 1975–2007. They concluded that in Pakistan, crime is affected by unemployment, poverty and inflation. Another empirical study by Tang (2009) investigated the relationship between crime, inflation and unemployment in Malaysia. Time series data have been used from the year 1970 to 2006. Empirical evidence reveals that inflation and unemployment have a positive relationship with crime. Buonanno and Leonida (2005) investigated the effects of education on violent crime and on property crime. They used panel data for the period from 1980 to 1995 of different regions of Italy. Their study revealed that there is a negative impact of high school enrollment on both crimes. This is because education promotes the virtues of hard work and honesty.

Qadri and Kadri (2010) had shown the relationship of crime with unemployment, inflation, investment, education and expenditure on health in Pakistan. They used time series data for the period from 1980 to 2010 for cointegration analysis among the crime and other explanatory variables. The empirical results showed that education had a positive significant effect on crime, whereas inflation and unemployment had been insignificant in two out of three types of crime. They suggested that the problems in the education system and the issues related to an educated person (as to get employed) in Pakistan should be addressed fairly.

Asghar et al. (2016) investigated the impact of different factors like education, unemployment, poverty and economic growth on violent and nonviolent crimes in Pakistan between 1972 and 2011. They have found a significant negative relationship between crime and higher education. They argued that more education directly prompts high earnings of any individual may also increase the opportunity cost of crimes. Their findings also revealed that poverty had a positive impact on crimes in the long run whereas negative impact in the short run. Anwar et al. (2015) had taken category wise crime in their study. They selected 25 districts of Punjab for empirical estimation. Panel data had been used for the period 2005–2012 by applying fixed and random effects models. The study revealed that education provides mixed findings depending on the nature of crime. Haider and Ali (2015) examined the socio-economic determinants of crimes in all districts of Punjab. Panel data had been taken for the year 2010–2011, and for the estimation they applied ordinary least squares (OLS) method. The socio-economic variables they used in their study were education, population density, unemployment, and remittances. The empirical findings of the study suggest that unemployment is positively related to the crime rate whereas level of education has a negative impact on crimes. Arshed et al. (2016) proved that increase in development expenditures leads to a decrease in the crimes reported in different districts of Punjab, Pakistan.

After exploring the economic factors, several studies had investigated the association between depression prevalence and environment quality with crime commitment. Recent empirical work has shown a heightened risk of violence in individuals with depression. Contemporary empirical work shows an amplified risk of violence among individuals with depression. A number of researchers have postulated that depression is associated with a range of adverse outcomes like medical complications, self-harm, and occasionally suicide.

An extensive study had explained the importance of well-kept green spaces that significantly changed the mental state of criminals, and consequently refrained them from committing a crime. Researchers had established the causality among green environment and depression, which helped decrease the crime rate (Grahn & Stigsdotter, 2003; Roe et al., 2013; Thompson et al., 2012). Therefore, well-kept lawns and greenery reduced the stress related illness and aggression which affects the mental state (Kuo & Sullivan, 2001a, 2001b).

Depression caused significant increase in the risk of violence among individuals. According to the National Institute of Mental Health, there were twice as many suicides as homicides in US in 2017 (47,173 suicides vs. 19,510 homicides). Fazel et al. (2015) demonstrated that depression is positively correlated to criminal activities and most often to violent crimes. The study had been conducted in Sweden, in which the author considered to take the violence risk assessment among those suffering from depression and clinical guidelines. Literature showed a positive association between mental health problems and delinquent activities (Fazel et al., 2012; Hein et al., 2017; Kroll et al., 2002; McCormick et al., 2017).

Association between mental health and delinquency has received considerable attention in literature. Several studies have documented negative emotions such as depression, as a motivating factor for delinquent behavior (Broidy & Agnew, 1997; Piquero & Sealock, 2004). People owing to mental illness and low self-esteem are more likely to give poor behavioral outcomes. They, perhaps, show aggression and delinquent behavior as well (Donnellan et al., 2005; Fuller-Thomson & Brennerstuhl, 2012; Hart et al., 2012; Maniglio, 2009; Silver et al., 2008; Teplin et al., 2005; Trzesniewski et al., 2006). Fazel and Grann (2006) had determined the population impact of patients with severe mental illness on violent crime which varies according to gender and age. The study showed that population-attributable risk fraction of patients was 5%. The results indicated that the depressed people with severe mental illness committed one in 20 violent crimes. This study confirmed the association of depressive symptoms with an increased in criminal behaviors.

Green spaces and clean environment are liked on account of many reasons, such as it catches urban flooding, good for health, and green spaces look awesome. Now a growing body of literature suggests that urban nature and environmental design significantly impacts crime. Such evidences are sought from empirical research studies which suggest that planting trees, well-kept lawns and greenery plays an important role in the safety of surroundings. A number of research studies have found a significant association between crime and green spaces maintenance. This mechanism can be associated with the theory that harkens back to Jane Jacob's view of “eyes on the street,” in which people got encouraged to spend more time outside if they have well maintained lawns and green areas which significantly contributed to informal surveillance of those areas and crimes which could be kept in control (Jacob, 1961).

Criminals may feel green areas as uncomfortable for committing crime without detection (Brontinghom & Brontinghom, 2013). Crime opportunity theory has drawn notable attention towards environmental criminology (Wilcox et al., 2003). The theory states that criminal activities occur when there are opportunities available to commit crimes to motivated individuals. Some researchers have demonstrated that vacant plots in the neighborhood increase the probability of criminal activities (Garvin et al., 2013; Garvin et al., 2013). There is a significant link between crime and vacant properties and is associated with fear of crime among the societies (Garvin, Branas, et al., 2013; Garvin, Cannuscio, et al., 2013; Hur & Nasar, 2014). Broken windows theory provides another rationale for how greening may reduce crime.

Donovan and Prestemon (2012) postulated that fewer trees are even (in the areas in Portland where the view is not clear) positively associated with an increase in crime occurrence. Whereas the probability of crime commitment is quite lower in areas with taller trees on private properties. Additionally, remediation programs for the gray areas or vacant properties, are shown helpful for crime control (Kondo et al., 2015).

The sense of security and safety can be enhanced by the maintenance of greens providing clean environment. People living close to green land feel more secure and safe as compare to the residents of vacant and untreated urban land (Garvin et al., 2013). Snelgrove et al. (2004) had explored the factors, and showed the negative association among the greenness index and the number of crimes committed.

Crime opportunity theory has drawn notable attention towards environmental criminology (Wilcox et al., 2003). This theory states that criminal activities occur when the opportunities to commit crime are available to motivated individuals.

The reviewed literature states that the maintenance of green areas, development of parks, and clean environment can positively influence crimes. Apart from the esthetic and ecological benefits, these measures probably create a secure environment for the residents of an area. Thus, urban environment is recognized as a cause of depression. Therefore, there is a dire need to intervene and cleanse the environment to reduce stress among individuals and to aid their mental well-being, which would resultantly lessen the crime rate.

2.1 Research gap

Previously, the research studies provided inconclusive outcomes in terms of the effect of income on the intentions to crime. Besides, very few studies have been done to assess the role of environmental quality and prevalence of depression on the intentions to crime. Thus, the present study envisages to explore the income dynamics using HDI.

3 ECONOMETRIC METHODOLOGY

The present study has employed quantitative time series as a research methodology. Further, in order to investigate the effect of different variables on crime rate, the researcher has taken violent crime as a dependent variable, and inflation, education, HDI, unemployment, environmental quality, and depression prevalence are used as independent variable.

3.1 Data sources

The sample selected for this study ranges from 1990 to 2017. The data has been extracted from the World Development Indicators, the Human Development Reports, the Ministry of Interior Pakistan and Website of Ouworldindata.org. The details of the variables are provided in Table 1.

| Variable | Description | Source | Data transformation |

|---|---|---|---|

| Dependent variables | |||

Violent Crime Rate (VCR) NonViolent Crime Rate (PCR) Total Crime Rate (TCR) |

Per capita crime is used as focusing on the separate analysis of violent crime, nonviolent crime and total crime in Pakistan | Data on these crimes are obtained data from Bureau of Police Research and Development, Ministry of Interior. | Per million capita violent crime rate (Natural Log) Per million capita nonviolent crime rate (Natural Log) Per million capita total crime rate (Natural Log) |

| Independent variables | |||

| Economic variables | |||

| Education (SSE) | Secondary school enrolment is taken as proxy for education. | Economic Survey of Pakistan World Development Indicator, World Bank (2019) |

Secondary school enrollment (net) |

| HDI | Human Development Index | Human Development Report (2019) | HDI index (0–1) |

| Unemployment (UNE) | Unemployed labor force | World Development Indicator, World Bank (2019) | Unemployed labor force as a percent of total labor force |

| General Prices (CPI) | Consumer Price Index | World Development Indicator, World Bank (2019) | Index of general prices market basked (Natural Log) |

| Environment and psychological variables | |||

| Environment Quality (CO2) | Carbon emissions per capita | World Development Indicator, World Bank (2019) | CO2 emissions in kt per capita |

| Depression Prevalence (DEP) | Depressed person per capita | Ouworldindata.org | Age standardized share of population with depression |

3.2 Functional form

(1)

(1) (2)

(2) (3)

(3)3.3 Independent variables and their relevancy

3.3.1 Education

Education represents the increase in the human capital component, which transforms the labor from unskilled to skilled. An increase in education enrollment is expected to increase the market wages. At first, an increase in education may increase the returns in the legal market, and second, if an educated criminal is caught he may waste his time, which could have been used to earn legal income (Coomer, 2003; Lochner, 2007). A number of empirical studies have also pointed out that substandard or irrelevant education may also prompt literate individuals to commit financial crimes (Anwar et al., 2017; Qadri & Kadri, 2010).

3.3.2 Environment quality

High level of air pollution puts life at risk in several ways, causing higher mortality. However, clean environment, proves good for health improvement and looks awesome esthetically, it also significantly impacts crime. Many research studies have found a significant association between crime and green spaces maintenance, advocate green areas within urban environments to alleviate some of the problems linked with crime, which includes promoting social communication among residents and greater feelings of safety (Kuo & Sullivan, 2001a). Violent crimes such as assaults and homicide are more likely to occur near unmaintained and vacant estates than well maintained areas (Culyba et al., 2016; Garvin et al., 2013). Researchers at the London School of Economics investigated the connection between air pollution and crime commitment, which may be due to increase in cortisol a stress hormone that is present in individuals exposed to higher pollution levels.

3.3.3 Prevalence of depression

Studies have investigated the association between depressive symptoms and crime commitment. Recent empirical work has shown a heightened risk of violence in individuals with depression. Contemporary empirical work shows an amplified risk of violence among individuals with depression (Fazel et al., 2015; Knoll, 2016).

3.3.4 Unemployment

Unemployment is witnessed as the most influential determinant which propels individuals to commit the crime. Thus, an increase in the unemployment rate decreases the opportunities for earning income, and instigating the individuals to commit crimes. The cost of committing crime is lower for unemployed workers, as suggested by Gillani et al. (2009). Altindag, Goel (2021).

3.3.5 Inflation

Inflation, taken as CPI, shows an adverse effect on the real income of the people. A survey conducted in inner cities of USA, described that crime was not merely affected by unemployed individuals, but inflation rate also played a crucial role in crime commitment (Curtis, 1981; Coomer, 2003; Jalil & Iqbal, 2010; Qadri & Kadri, 2010).

3.3.6 HDI

For any economy, consistent improvement in living standards is considered as a key to sustaining crime reduction (Hovel, 2014). By way of contrast, lower levels of human development and income occur in parallel with high and very high rates of armed violence (more violence, less development). Ethnic minorities and other groups are often excluded from education, employment and administrative and political positions, resulting in poverty and higher vulnerability to crime, including human trafficking (UNDP, 2012).

3.4 Estimating strategy

From the functional form, it is expected that when the equilibrium forces favor the conditions to employ in the market of violent or nonviolent crime, we will experience an increase in the crime rates at the national level. To estimate the effect of independent variables on dependent, the historical patterns must be compared to evaluate proportionality coefficient. Such methodological objectives can be achieved using regression analysis. But, with an increase in length of longitudinal data, changes in priorities, culture, knowledge, technology level, or frequent policy interventions change the pattern of data. Such deviations from the random behavior can be tested using unit root tests (Gujarati, 2009).

This study has availed augmented dickey fuller (ADF) (Dickey & Fuller, 1979) and kwiatkowski–phillips–schmidt–shin (KPSS) (Kwiatkowski et al., 1992) tests, based on which if the variables found out to have experienced a shift in mean as compared to past (nonstationary behavior), then such data sets cannot be evaluated using simple regression.

It can be assumed, when the series shows frequent shifts in means or variances in time, that some policy intervention or human action is modifying it to reach a certain mean value in a long term horizon and trying to ensure the deviations in short run vary around this path. The modified version of regression which is appropriate for estimating this long run and short run behavior is known as ARDL with cointegrating bounds (Pesaran et al., 2001). The advantage of this ARDL model over other models is that this model can handle stationary and nonstationary variables together. Studies like (Anwar et al., 2017; Hassan et al., 2016; Inabo & Arshed, 2019; Kalim et al., 2016) have used the ARDL model in different disciplines.

4 RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

4.1 Descriptive statistics

Based on the sample of 28 years, the following Table 2 provides the descriptive statistics to assess the nature of the variables. Here it can be seen that the mean value of all the variables is higher than its standard deviation, this shows that the data is closely scattered around a certain mean. Based on Jarque Bera test of normality, at 1% level, all the variables are normal. Further, the VIF test is employed, showing no multicollinearity among the selected variables.

| PCR | VCR | TCR | CPI | HDI | DEP | CO2 | SSE | UNE | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean | 3.70 | 3.45 | 5.73 | 4.02 | 0.48 | 3.43 | 0.79 | 29.56 | 4.04 |

| Std. Dev. | 0.17 | 0.23 | 0.14 | 0.67 | 0.05 | 0.08 | 0.09 | 7.88 | 2.48 |

| Skewness | −0.17 | −0.94 | 0.05 | 0.08 | 0.03 | −0.46 | −0.17 | 0.72 | −0.13 |

| Kurtosis | 1.71 | 3.06 | 1.62 | 1.87 | 1.55 | 1.44 | 1.88 | 2.39 | 1.72 |

| Jarque-Bera | 2.09 | 4.12 | 2.22 | 1.52 | 2.45 | 3.83 | 1.60 | 2.83 | 1.97 |

| Probability | 0.35 | 0.12 | 0.33 | 0.47 | 0.29 | 0.14 | 0.45 | 0.24 | 0.37 |

| Observations | 28 | 28 | 28 | 28 | 28 | 28 | 28 | 28 | 28 |

Table 3 reports the unit root tests based on the ADF and KPSS methodology. These tests are used with intercept and no trend specification. Since the probability values of ADF test in level are above 0.05 and at first difference, is below 0.05, while all KPSS values at level are above critical values and at first difference, less than critical values, thus all the variables are nonstationary in nature. This means that through 28 years, the natural pattern of these variables is altered because of policy intervention, change in culture, or technology. Ironically, the learning which is gained from the OLS approach has led to a change in our behaviors which had led to the redundancy of OLS. Pesaran et al. (2001) had proposed an alternative model which accounts for the effect of past indicators on the present change, and ultimately generation of an equilibrium model.

| At level | 1st difference | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Variable | ADF test (Prob) | KPSS test | Decision at level | ADF test (Prob) | KPSS test | Decision at 1st diff. |

| PCR | −1.880 (0.34) | 0.137 | Mixed | −5.140 (0.00)* | 0.130 | Stationary |

| VCR | −0.246 (0.92) | 0.136 | Mixed | −4.913 (0.00)* | 0.273 | Stationary |

| TCR | −1.470 (0.53) | 0.662* | Nonstationary | −5.398 (0.00)* | 0.071 | Stationary |

| SSE | 1.008 (0.99) | 0.619* | Nonstationary | −4.030 (0.00)* | 0.220 | Stationary |

| HDI | 2.670 (0.99) | 0.732* | Nonstationary | −5.288 (0.00)* | 0.583 | Stationary |

| CPI | 0.626 (0.98) | 0.731* | Nonstationary | −3.071 (0.04)* | 0.148 | Stationary |

| UNE | −0.547 (0.86) | 0.732* | NonStationary | −3.883 (0.00)* | 0133 | Stationary |

| DEP | −1.710 (0.41) | 0.457* | Nonstationary | −2.929 (0.05)* | 0.264 | Stationary |

| CO2 | −2.404 (0.15) | 0.664* | Nonstationary | −5.692 (0.00)* | 0.384 | Stationary |

- Note: KPSS Critical values 0.739 @ 1%, 0.463 @ 5% and 0.347 @ 10%. *Significant at 5%.

The estimation statistics of the ARDL model are provided in Table 4, in which it can be seen that the F bound statistic is above the critical value of total crime rate (TCR), violent crime rate (VCR) and nonviolent crime rate (PCR) model, which confirms that even though the variables are nonstationary and taking feedback from the past, still their co-movement is significant enough to suggest that there is a causal effect of independent variables on the dependent variable. Further, the quality of this relationship can be assessed from the fact that the explaining power of independent variables is 97% for TCR, 98% for VCR model and 97% for PCR model. For the evaluation of the reliability of the model, an array of four tests are provided such as serial autocorrelation, functional form, normality and heteroscedasticity. Since all of these tests came out insignificant, it can be safely said that model is valid and reliable at 10%. Moreover, the researcher has tested the reverse models using independent variables and dependent variables to ensure no reverse causality. This ensures that the estimates are consistent.

| TCR model TCR = f(SSE, CO2, DEP, HDI, UNE, CPI) | VCR model VCR = f(SSE, CO2, DEP, HDI, UNE, CPI) | PCR model PCR = f(SSE, CO2, DEP, HDI, UNE, CPI) | |

|---|---|---|---|

Optimal Lag Order (1,0,2,1,2,2,2) |

Optimal Lag order (1,0,1,2,0,0,0) | Optimal Lag order (1,2,0,2,0,2,2) | |

| F-statistic | 3.038 | 7.334 | 6.097 |

| 95% Upper bound | 3.24 | 2.24 | 2.24 |

| 90% Upper bound | 2.87 | 2.87 | 2.87 |

| Diagnostics Test | |||

| Test statistics | F Version | F Version | |

| A: Serial correlation | 0.581 [0.465] | 2.849 [0.092] | 5.736 [0.157] |

| B: Functional form | 1.207 [0.339] | 1.744 [0.216] | 0.480 [0.641] |

| C: Normality | 0.595 [0.742] | 0.022 [0.969] | 3.674 [0.159] |

| D: Heteroscedasticity | 0.212 [0.656] | 0.782 [0.645] | 2.498 [0.074] |

| CUSUM | Stable | Stable | Stable |

| CUSUMsq | Stable | Stable | Stable |

| R-squared | 0.974 | 0.983 | 0.966 |

| Adjusted R-squared | 0.936 | 0.973 | 0.923 |

| DW-Statistics | 2.247 | 2.63 | 2.90 |

- Note: [] – Probability values.

Table 5 provides the estimates of the long run model where the independent variables affect the mean value of the dependent variables. Here 1% increase in education enrolment will increase total crime by 0.03%, decrease violent crime by 0.02% and increase property crime by 0.03% on average. The negative effect on violent crimes is higher as education makes people more ethical and hardworking. Masih and Masih (1996) have reviewed 52 studies to support this inconclusive relationship, from which 33 studies have shown a positive relationship, and 19 have shown a negative relationship with crime. Further, 1% increase in the development level leads to 9.64% decrease in the overall crime rate and 14.23% decrease in the nonviolent crime rate. UNDP (2016) focuses on promoting development and social cohesion to reduce social unrest.

| TCR model | VCR model | PCR model | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Regressors | Coefficient [Prob] | Coefficient [Prob] | Coefficient [Prob] |

| SSE | 0.03 [0.03]** | −0.02 [0.00]*** | 0.03 [0.08]* |

| CO2 | 6.08 [0.01]** | 2.09 [0.01]** | 0.56 [0.74] |

| DEP | 1.33 [0.00]*** | 0.88 [0.00]*** | 1.59 [0.00]*** |

| HDI | −9.64 [0.06]* | 0.86 [0.67] | −14.23 [0.02]** |

| UNE | 0.03 [0.30] | −0.03 [0.01]** | 0.07 [0.08]* |

| CPI | 0.05 [0.77] | −0.20 [0.06]* | 0.75 [0.03]** |

- Note: *** significant at 1%, ** significant at 5% and * significant at 10%.

Similarly, 1% increase in unemployment significantly decreases violent crimes by 0.03% and increases nonviolent crimes by 0.07%. These results are similar to Gillani et al. (2009), and Altindag. 1% increase in the general prices leads to 0.20% decrease in violent crimes while 0.75% increase in nonviolent crimes in long run. These results are similar to Curtis (1981), Coomer (2003), Jalil and Iqbal (2010) and Qadri and Kadri (2010).

Here, 1% depreciation in the quality of the environment leads to 6.08% increase in the overall crime rate and 2.09% increase in the violent crime rate, as suggested by (Fazel et al., 2008; Knoll, 2016). Furthermore, 1% increase in depressive disorder leads to 1.33% increase in the total crime rate, 0.88% increase in violent crime rate and 1.59% increase in nonviolent crime rate. The outcome is similar to Culyba et al. (2016) and Garvin et al. (2013).

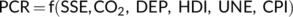

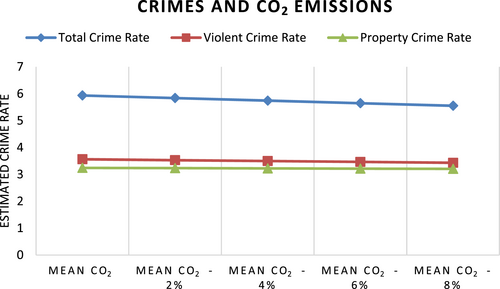

Figures 3 and 4 provide the incidence of crime for a simulated decrease in the CO2 emission and depression prevalence. The methodology is adapted from Hassan et al. (2021), whereby other independent variables are assumed to be at the mean value, and the estimated dependent variables are calculated for new values of one variable. Here we can see that CO2 emissions tend to have a similar effect on violent and property crime, while depression tends to decrease property crime more than the violent crimes.

source: Self calculated

)

source: Self calculated

)The feasibility of the long run equilibrium is assessed by how quickly the short run model converges into the long run model. Here in Table 6, the ecm(−1) coefficient of −0.87 for TCR, −0.89 for VCR and −0.72 for PCR depicts that any policy intervention in the model via independent variable changes the equilibrium position and how the dependent variable will move towards this new equilibrium. Hence we can expect social policy targets to be realized in around 1.1 years for TCR, 1.1 years for VCR and 1.4 years for PCR. In the short run total crime rate, the present value of education, and depression are significant. For short run violent crime rate, the present value of education, environment quality, unemployment, and inflation are significant variables. For the short run nonviolent crime rate, variables like education, depression, HDI, and inflation are significant.

| TCR model | VCR model | PCR model | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Coefficient [Prob] | Coefficient [Prob] | Coefficient [Prob] | |

| dSSE | 0.02 [0.02]** | −0.02 [0.00]*** | 0.03 [0.01]** |

| dSSE −1 | 0.02 [0.11] | ||

| dCO2 | −0.82 [0.31] | 1.03 [0.07]* | 0.40 [0.74] |

| dCO2 –1 | −4.36 [0.00]*** | ||

| dDEP | 6.81 [0.02]** | 5.55 [0.00]*** | 5.38 [0.03]** |

| dDEP –1 | −6.28 [0.00]*** | −10.17 [0.00]*** | |

| dHDI | −7.84 [0.12] | 0.76 [0.67] | −10.22 [0.01]** |

| dHDI –1 | −9.88 [0.10] | ||

| dUNE | −0.001 [0.89] | −0.02 [0.01]** | −0.02 [0.16] |

| dUNE −1 | −0.02 [0.07]* | −0.04 [0.04]** | |

| dCPI | 0.89 [0.18] | −0.18 [0.06]* | 2.43 [0.01]** |

| dCPI –1 | −1.20 [0.07]* | 1.06[0.12] | |

| ecm(−1) | −0.87 [0.00]*** | −0.89 [0.00]*** | −0.72[0.00]*** |

- Note: *** significant at 1%, ** significant at 5% and * significant at 10%.

5 CONCLUSION AND POLICY RECOMMENDATIONS

The study investigates the factors which affect violent and nonviolent crimes in Pakistan. Its scope is to report the role of various socio-economic, environmental, and psychological variables to discuss the violent behavior of a society. For this purpose, we have taken the data from 1981 to 2017 to explore the long run relationship between violent and nonviolent crime and its factors in Pakistan. Since time series data is usually nonstationary, this study has applied stationarity test to confirm it and then used Pesaran et al. (2001) cointegration test to find cointegration between violent and nonviolent crime. Further, this model helped in estimating the long run and short run coefficients. Diagnostics and stability test has also been applied to confirm the validity of the model.

Instead of considering criminal behavior as a result of mental or moral deficiencies, it is now considered a possible result of a utility maximization problem. The individual considers crime by comparing his possible returns from criminal activity against the returns he would receive from participating in a legal market activity (Becker, 1968). Therefore, lowered crime rates can be achieved by reducing the relative benefits of criminal behavior and by reducing the gains from crime, raising the probability of being caught, increasing the severity of punishment, or making the opportunities of legal market activity more attractive and widely available.

Based on empirical findings, it can be seen that the indicators as unemployment and inflation are not motivating violent crimes since the individual is merely in need of financial impetus due to which he commits nonviolent, property, or financial crime. Moreover, education cannot restrict (as moral barrier) the individuals from committing nonviolent crimes. The newly proposed indicators like environment quality and depression have more severe effects as they too motivate violent crimes. The most effective indicator to reduce overall crime is HDI, which proposes that government should necessitate for the development initiative coupled with stabilized prices, to create employment, and access quality education which would certainly reduce the overall crime rate. Government needs to ensure better quality of environment and the mental health of individuals which will help reduce the violent crimes.

The study has few limitations such as it assumes no external influence on the behavior of crime in Pakistan. However, the variables used like CO2 and depression could also be effected by the globalization and neighboring economies. Future studies could estimate this model using panel data.

Biographies

Ms Sadia Yasmin is a PhD Scholar in Department of Banking and Finance and MS Economics. She is expert in development economics and Islamic finance.

Dr Muhammad Shahid Hassan is assistant professor in economics with an experience in development economics and international trade.

Dr Noman Arshed is assistant professor in economics with experience in econometrics, development economics and Islamic finance.

Dr Muhammad Naveed Tahir is assistant professor in economics with experience in monetary and development economics.

Open Research

DATA AVAILABILITY STATEMENT

Data sharing is not applicable to this article as no new data were created or analyzed in this study.