Governance matters. Fieldwork on participatory budgeting, voting, and development from Campania, Italy

Abstract

On the wave of the success of the participatory budgeting (PB) implemented in Porto Alegre, Brazil, a number of administrations around the world jumpstarted new forms of nonfinancial balance reporting. This trend was supported by an increasing consensus from the international community. PB aims to enhance mutual trust between the different social stakeholders and foster public administrations transparency. For this reason, PB is recognized as an effective tool for facilitating good governance, sustainability, and development. Previous field research does not highlight local voting and corruption figures. To shed light on these variables throughout a case study, this article makes use of original mixed methods techniques to analyze the PB experience of a municipality in Southern Italy. The combination of data regarding census, voting shares, and projects' features is a methodological innovation, used here for the first time. Fieldwork has been conducted to collect both quantitative and qualitative data. These data were employed along with official demographics statistics to inspect existing public management and development dynamics. Four distinct data sources, intersecting population and voting data through the PB tool were examined. After mainstreaming PB, referring to the world's benchmark of Porto Alegre, this article investigates the good practice of Casamarciano, Campania. Evidence shows compelling features from the local experience and encouraging involvement of the community, rating the poll participation even greater than Porto Alegre engagement. The qualitative data pinpoints the local administration's management choices—noteworthy, the town's PB model—and the innovation behind the public management strategies. These outcomes may help to better understand PB dynamics, yielding improved local development and sustainability indications for public affairs governance.

“Nel fango affonda lo stivale dei maiali” (Battiato, 1991)

1 INTRODUCTION

Facing corruption is a focal action for facilitating economic development, social change, and long-run growth. The need for transparency in politics and media became urgent in countries that are severely affected by corruption. The subject of considerate management of public institutions is no news in public affairs and development scholarship (Caputo & Di Cagno, 2010; Shirley, 2005). Besides, the related literature considers efficient and effective governance of resources essential in the pursuit of acceptability and adequacy criteria. International organizations individuated anti-corruption, transparency, and participative democracy as core goals to foster domestic governance performance. On the same page, the enlargement of citizens participation has been designed as a pillar to improve sustainable development results (Bland, 2011; Goldsmith, 1999; UN, 2015; UNDP, 2017; Wampler, 2010).

Good governance, transparency, and anti-corruption are central in international development policy. The United Nations' Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) identify governance as an intangible development factor (UN, 2015). This implies a lead role to transparency and corruption as sustainable development pillars, attributing importance to institutional and government spending quality in its economic, social, environmental, and political dimensions (Mammadli et al., 2021; Sadik-Zada & Gatto, 2021). The World Bank's Anti-Corruption Strategy is based on promoting the ultimate goal of ending extreme poverty by 2030 (Shah, 2007; Shah & Huther, 1999). Quantifying these complex phenomena is not an easy task, though substantial efforts are being produced. With the purpose of measuring these phenomena, the World Bank Global Governance Index (WGI) and the Corruption Perception Index (CPI) by Transparency International have been implemented as some of the most widely used and popularized metrics—both for research, policymaking, and media purposes (Transparency International, 2016; WBI, 2014).

Tackling corruption is a particularly urgent issue in Italy where it has become a structural plague. From Mani Pulite to Mafia Capitale, the news of rigged contracts, bribes, and public–private collusion appeared as overriding orders of the domestic political agendas (Sargiacomo et al., 2015). As confirmed by international shreds of evidence (Ortega et al., 2014 and 2016), these issues severely limit the prospects for growth and human development—and most notably in the South of the country (Fiorino et al., 2012; Golden & Picci, 2005). In this alarming framework, important tools for local administration's transparency empowerment such as participatory budgeting (PB) may be adopted as a preliminary action for restoring an urgent need in trust toward the institutions and the community. This may eventually help to prevent local corruption and reallocating public resources toward sustainable development assets.

Italy is advancing new financial instruments and concepts in the last three decades (Grossi et al., 2016). There, a noticeable innovation—the management executive plan—has been developed since 1995. In this sense, PB can reveal significant results to public affairs governance (Bell & Hindmoor, 2009) with regard to the democracy–governmentality–transparency triangulation (Brun-Martos & Lapsley, 2017). This shall be attributed to the fact that by increasing the level of citizens' participation toward direct democracy and budget transparency, local administrations are supposed to become more prone to render better accounting performance and decreased corruption. However, to date, research interest on PB as a tool to easing corruption rates has been meager. As a result, the need for contributions to fill this research gap emerges.

PB is strictly intertwined with empirical analysis of local practices. As such, PB calls for case studies examination. A large number of local experiences have, indeed, been examined by foregoing studies. When it comes to Italy, previous publications have been exploring local projects. However, past scholarship is circumscribed within a few shreds of academic research and experiences and none of them has been inspecting the good practice of Casamarciano in Campania (Allegretti & Stortone, 2014; Bassoli, 2012; Fedele et al., 2008; Stortone & Allegretti, 2018). In addition, these pieces of research did not have the threefold mandate carried on in this article—PB case study, citizens' voting, and corruption dynamics within the development and governance framework. This fact calls for new investigations and justifies the need for this inquiry. The importance of inclusive decision-making to attain participatory local planning and territorial social responsibility has been demonstrated (Rusciano et al., 2019).

Moreover, people's participation is a frequently stemming issue in PB (Johnson et al., 2021; Sintomer, Herzberg, et al., 2013; Sintomer, Traub-Merz, et al., 2013). Voters' engagement can happen through a variety of modalities (Miller et al., 2019)—some of which will be extensively discussed in this paper's results section, focusing on Casamarciano. More recently, citizens' involvement in PB voting has been including a set of new tools such as social media (Gordon et al., 2017). This array of alternative voting systems turns crucial when traditional poll techniques are not possible. This aspect is of particular importance for COVID-19 and further pandemics and finds broad applications to remote activities—as remarked during the 2020 US presidential elections (Harris & Moss, 2020; Landman & Di Gennaro Splendore, 2020; Thompson et al., 2020). Both distant and in-person voting shall be considered for PB voting, implementing a proper mixed voting range (Miori & Russo, 2011). Being explorative tools, these novel modalities pave the way for possible application in elections and more incisive voting and shall return important insights to confute the emerging non-regularity claims in remote voting and the consolidated irregularities in traditional voting in some world's regions. More broadly, the issue of participation is prone to up-to-date investigations and deserves extensive scholarly attention and concrete applications analyses.

This article focuses on the PB experience of Casamarciano, Italy. The aim is to explore data on voting share and the local population, as well as management and development features. To meet these purposes, original mixed methods techniques are exploited. Field interviews collected data on the local PB model, voting, and population figures. These are completed by voting and population data on the world's benchmark—Porto Alegre, Brazil. Eventually, these indications can help to elicit local corruption, criminality, and sustainable development policy speculations.

The three claimed hot bottom issues—case study viz. Italy, citizen's participation, and corruption—and the relative topical research gaps have shaped this work's research question. PB as a public affairs tool shall be indicative of motivating the need for such types of investigations. For these reasons, the paper at hand proposes offering a contribution to the existing scholarship on PB as a public management instrument, highlighting: (i) a case study (for a Municipality in Italy); (ii) local population's voting; and (iii) corruption. For this scope, the quantitative analysis of the voting shares within the local municipality is coupled with qualitative data from the field on the public management decisions regarding the PB preferred modalities. These data are corroborated with local census data. The analysis is carried forward within the broader development and governance discourse.

The article proceeds as follows: Section 2 draws the state-of-the-art of corruption, good governance, and transparency, exploring the current measurement tools worldwide, and focusing on a case study from Campania, Italy. Section 3 recalls the worldwide experiences of PB, emphasizing the pilot project of Porto Alegre (POA), Brazil. Section 4 sketches the data and methodology employed for conducting this research. There, details on domestic data and fieldwork data collection and techniques are provided. Section 5 presents the case study of Casamarciano (CM), Italy. There, the fieldwork results about both the local population's voting shares and the budgeting strategy opted from public management are examined. These data are collated with local census data from the case study and the pilot project. Section 6 concludes and projects prospective policies and studies.

2 PARTICIPATORY BUDGETING AND DEVELOPMENT

2.1 Public management, corruption, and sustainable development

PB is regarded as a public management tool to possibly contributing to boost transparency and good governance in public affairs. PB acts by easing corruption figures, and potentially fostering local administrations' effectiveness and democratic development (Bland, 2011; McCourt, 2008; Wampler, 2012). PB is an open government tool, a source of social innovation that can be regarded as a solution for complex systems within public management and diverse organizations (Ewens & van der Voet, 2019).

As part of nonfinancial disclosure, PB is tightened with CSR, ethics, and sustainability. PB can be a sustain to directly tackle urban environmental, social, and governance issues (Calisto Friant, 2019a; Allegretti & Hartz-Karp, 2017). It is, indeed, an instrument that allows involving the entirety of stakeholders groups—both in public, private sector, and civil society groups (Coronella et al., 2018; Gatto, 2020). Nonfinancial reports may also help to address the unattended demand or needs for performance information within diverse organizations (Grossi et al., 2016). Considering the difficulties in assessing sustainable development and CSR achievements (Venturelli et al., 2017), PB may be used as a social innovation tool to facilitate CSR and public or nonprofit organizations performances, improving local communities wellbeing on a range of socioeconomic, governance, and environmental criteria (see Cattivelli and Rusciano, 2020).

It shall be remarked that, following Directive 2014/95/EU on nonfinancial information, starting from 2017, large companies must provide public disclosure on social, governance, and environmental parameters (Venturelli et al., 2019; Venturelli, Caputo, Cosma, et al., 2017; Venturelli, Caputo, Leopizzi, et al., 2017). The firms are subject to compliance procedures and assessment. The EU Directive was transposed into the Italian legal system through the Legislative Decree 254/2016. In spite of the partial impact on domestic compliance, these regulations contributed to ameliorating the rates of disclosure of nonfinancial reporting (Caputo et al., 2019; Venturelli et al., 2019). As a reflex, sustainability performance benefits from those improvements. However, firms seldom explicitly disclose information on SDGs, indicating the need for revisiting mandatory nonfinancial reporting—including sustainable development subjects and transparency on social, environmental, and governance practices (Pizzi et al., 2021).

Scholarly, it has been openly referred to PB as an instrument to improve sustainable development, acting on both the socioeconomic side of development and the environmental and governance performance (Allegretti & Hartz-Karp, 2017). Further to sustainable development, the possible impact of PB in improving wellbeing, quality of life, and health has been successfully determined (Boulding & Wampler, 2010; Campbell et al., 2018; Hagelskamp et al., 2018). PB can be fundamental in contributing to addressing specific social goals, including the empowerment of women, the poor, and the vulnerable. Furthermore, PB may help to raise the bar of citizens' competencies and cementing community-agreement building (Baiocchi & Ganuza, 2014; Lerner, 2011; Talpin, 2012).

However, noteworthy caveats exist. This includes the project's effectiveness. As it will be thoroughly examined in the next sections, the risk to turn PB into mere propaganda is high. Additionally, PB is no plea against corruption—it is simply a tool to possibly alleviate it. On top of that, relevant inhabitants participation needs to be gauged and ensured. Lastly, the project's sustainability overtime needs to be guaranteed (Christensen & Grant, 2016).

2.2 Corruption, transparency, and good governance: Definitions and measurements

Since the 90s, a number of methodologies and tools have been implemented to address or sum up governance, corruption, democracy, and citizen participation and control (Lyrio et al., 2018; Neshkova & Kalesnikaite, 2019; Shim & Eom, 2008). The WGI has been published since 1996. It analyzes over 200 worldwide countries. The six chosen indicators are: (i) freedom of expression and responsibility; (ii) political stability and the absence of terrorism; (iii) government effectiveness; (iv) regulatory quality; (v) rule of law; (vi) control of corruption (WBI, 2014). The 2013 Index confirms that the most critical areas are South America, sub-Saharan Africa, and most of the Asian countries.

Italy performs poorly, ranking at 58th place in terms of control of corruption and even 76th place in the perception of citizen's participation and reliability of the administrations (WBI, 2014). The CPI has been drafted since 1994 by Transparency International and currently entails 162 countries. The index brings back the subjective perception of citizens toward the phenomenon of corruption, gauged into a composite indicator (scoring countries from 0 to 10). In 2015, 12 indicators were drawn up by various institutions and issued by Transparency International. The variables included institutional policies, economic and geographical risks, competitiveness, and justice. For 2015, the results somehow approximate the World Bank Index ranking. As far as Italy is concerned, performance remains medium-low in issues such as corruption, transparency, and good governance, scoring penultimate in the EU28 (Transparency International, 2016).

Methodological ameliorations in the measurement and development of synthetic indicators are helping in improving national government policies by promoting effective, efficient, and timely interventions (Drago & Gatto, 2018). In terms of corruption, transparency, and good governance, these stylized facts are corroborated by many indicators that globally convey in attributing poor performances to Italy (Transparency International, 2016; WBI, 2014). This trend has deepened in the 90s when the Italian Parliament was involved in a serious public corruption scandal, Tangentopoli (i.e. bribes city), uncovered by the judicial investigation Mani Pulite (namely, clean hands) (Vannucci, 2009). Italy is also a huge business area for criminal organizations, spread in the country like cancer, affecting the social, economic, environmental, and political spheres (Del Monte & Papagni, 2007). This public–private collusion damages particularly Southern Italy through bribes, extortions, frauds, traffic, money laundering, nepotism, and clientelism. As underlined by the international community, corruption episodes become often an unsustainable cost for a country, as well as for global governance, determining severe ineffectiveness for business and economic growth (UN, 2015).

In the last years, a vast area of Naples and Campania jurisdiction became renowned as “terra dei fuochi” (viz. land of fire), being garbage and its disposal – along with procurement, construction, and illegal trade and management—the core camorra business (Giordano & Chiariello, 2015). Most of this area has been affected by severe socioeconomic deprivation and poor levels of environmental quality. This situation has generated a case study for sustainability failure (Agovino et al., 2021). In this scenario, heavily unsustainable waste management has become the rule. In this context, linkages between politicians and criminal groups have often been reported. When demonstrated, these proofs lead to the common practice of the dissolution of the local council.

3 PARTICIPATORY BUDGETING AROUND THE WORLD

3.1 Global participatory budgeting experiences

Many policy solutions have been implemented in the attempt of tackling corruption and addressing good governance. A way to solve these problems is to uptake transparency tools. Among these, PB stemmed as an economic instrument that obtained success in the last years. For PB, Porto Alegre is often referred to as an international benchmark. PB became popular also in a number of OECD countries, where some towns decided to devote a portion of their budgets to their citizens' priorities and choices. This is the case of Casamarciano, a municipality sitting within the metropolitan area of Naples. In 2012, Casamarciano municipality first introduced PB (Comune di Casamarciano, 2018).

From its pilot model in POA, PB has been experiencing a diffusion all over the world, highlighting some of its peculiar strengths and limitations (Goldfrank, 2012; Sintomer, Herzberg, et al., 2013; Sintomer, Traub-Merz, et al., 2013; Wampler et al., 2018). All along with its blooming, different models have been globally implemented. The spatial dimension and different case study techniques highlight the importance of examining geographical evidence. These experiences include differently designed cases from Europe (Sintomer et al., 2008; Sintomer, Herzberg, et al., 2013; Sintomer, Traub-Merz, et al., 2013). This includes both European democracies such as France, Germany, and the UK (Röcke, 2014) and transition economies in Europe—Poland (Polko, 2015), Romania (Boc, 2019), and Russia (Tsurkan et al., 2016). PB has also been analyzed for selected practices gemming in North America—the United States (Hagelskamp et al., 2018; Russon Gilman & Wampler, 2019) and Canada (Pinnington et al., 2009)—, Latin America (Peixoto et al, 2020; Russon Gilman & Wampler, 2019; Bland, 2011), Asia (He, 2011; Sintomer, Herzberg, et al., 2013; Sintomer, Traub-Merz, et al., 2013), and Africa (Marumahoko et al., 2018; Matsiliza, 2012). As previously mentioned for Italy, besides the development stage, the level of one country's democracy is another determinant factor to be assessed when dealing with PB.

3.2 The international benchmark: orçamento participativo in Porto Alegre

On the aforementioned baseline, PB emerged as an instrument of democratic participation, involving the whole population in the decision-making process for a portion of the local budget. Enabling the share of public expenditure, PB has been formulated to reach the following governance goals: (i) increasing the transparency of fiscal policy and public expenditure management; (ii) reducing corruption episodes; (iii) maximizing the participation in the political process through the advancement of public accountability and electorate trust (WB, 2013). Furthermore, PB was reputed as a concrete tool to build a good urban and socioeconomic governance (Cabannes, 2004; UN, 2015; Wampler, 2000).

Even though it does not exist a unique model of PB, one can mainstream the process into three stylized moments: (i) information: the population acquires the knowledge about the flow; (ii) consultation: public meetings among the parts—usually followed by negotiation and consensus-building—take part; (iii) institutionalization: polls and enlightenment of the investments are run (WB, 2013). In this process, it is fundamental the monitoring and auditing of the whole process. The success of Porto Alegre led a series of municipalities to adopt PB (140 over 5571 municipalities, the 2.5% of Brazil; Porto Alegre Municipality, 2014). PB has been often a useful strategy to launch additional nonfinancial balances (e.g., social budgeting, ethical budgeting, and further oriented budgets). On top of that, PB has often been pointed out to play an active role in fighting determinant failures of local governance.

PB outcomes diverge from big cities to local municipalities. Concerning the pilot project of the orçamento participativo (OP) developed in POA, the business affair involves some 200 million dollars of investments per year. The portion of the municipal budget started from 10% to reach 25% of the whole budget (Prefeitura de Porto Alegre, 2013). OP has significantly improved the quality of urban governance, dramatically fighting clientelism and corruption. This has been achieved by whittling inequality and spreading the political and social participation needed to enhance governance accountability and mutual trust (WB, 2013; Wampler, 2000, Souza, 2001; Goldsmith, 1999).

Porto Alegre has been ranked by the UN among the 40 best urban public governance, withdrawing a great contribution from PB and designed by the WB as a best practice of urban participation and emancipation (Célérier & Botey, 2015). Today POA's human development index is the highest in Latin American cities (UNDP, 2017; Wampler, 2010). This data was confirmed by the spread and increased rates of schooling and health standard and trade boosting, significantly nudged by the PB action (Calisto Friant, 2019a; Novy & Leubolt, 2005).

4 DATA AND METHODS: PRIMARY AND SECONDARY DATA

The paper at hand exploits mixed methods techniques. Secondary data on local demographics were combined with primary data. The latter included qualitative and quantitative data collected in the field. With regard to quantitative data, this work benefited from domestic data on national censuses—from both the Brazilian and Italian national statistics offices—and ground data. The former came from the national Brazilian and Italian censuses (Instituto Brasileiro de Geografia e Estatistica [IBGE] and Italian National Institute of Statistics [ISTAT]). From the national censuses, local demographic data were extrapolated to examine population shares. The latter were derived through fieldwork.

Qualitative data were acquired by means of fieldwork techniques. Semi-structured interviews with local experts were organized. The interviews returned key information and data on the voting and on the whole local PB process, highlighting the participatory phases and the public management strategies and development drivers.

Additionally to these qualitative data, open-ended interviews rendered important information on selected topics—for example, the decision process, the framework, and the pursued options. These interviews were addressed to key stakeholders and local experts interested in the community PB and whose identity will not be disclosed in observance of the general data protection regulation enforced in the EU. Further to this, quantitative data on the voting population of local citizens shares for the case study were collected and collated to the pilot benchmark. The experts were selected, contacted, and eventually met vis-à-vis during separated scheduled meetings. The interviewees pertained to different stakeholders public affairs categories—policymaking, accounting, economic, and technical domains. The outcomes from the interviews were notated, verbatim recorded, categorized, and processed. The results furnished key qualitative and quantitative information for this research that has been systematized, organized, analyzed, and presented.

To the best knowledge of this inquiry's authors, no previous study combined these mixed methods techniques before—either for studying PB or for examining different topics. Therefore, the novelty of mixing these methods—census, voting, and project's analysis approach—may be considered a further added value of this article.

5 RESULTS: BILANCIO PARTECIPATIVO IN CASAMARCIANO

5.1 Premises

On the basis of the heritage accumulated from international PB experiences, whose POA has been a trailblazer, the council of Casamarciano started in 2012 the ambitious, pioneering project of implementing a PB within a difficult area, amidst a severe economic recession. Applying the WB mandate to a small context means localizing the global good governance prescriptions into a tiny town of only 3500 inhabitants (as compared to Porto Alegre large population of 1,500,000 inhabitants). In line with the OP case, Casamarciano small local administrations aimed to address the international development recommendations to the local exigences in order to build a new concept of governance and development.

If it is true that Casamarciano is a small town, one shall report that the share of participation reached in the first 5 years is higher than the most recurrent global evidence. When compared to the successful case of POA, the first 5 years of voting achievements that occurred in CM are even larger than POA ones. Furthermore, CM PB must be considered as an important signal for the implementation of important tools of governance enhancement. In these terms, CM PB has just started showing its potential. A determinant contribution might come from regional support, as it happened for the Latium region in Italy (Ciaffi & Mela, 2011).

5.2 The strategy

- engaging the whole population;

- overtaking the 10% share of the budget devoted to PB;

- avoiding strategic desertions;

- planning the timelines, the bottlenecks, and factors slowing down the process (Comune di Casamarciano, 2018).

PB offered a base to participative democracy, providing a more effective voice to the citizens and increasing public transparency and corruption control. This could eventually lead to wide accountability of the administration, needed to establish mutual trust among the social stakeholders.

- identification of projects and investments by the administration;

- voting (Comune di Casamarciano, 2018).

- Information: in this phase, the participatory process and material are shown. The minimum length of this process is planned to last 15 days. It is advertised with a specific public notice containing the indication of the participation activities, the procedures for carrying out the project, timing, and any other useful information to encourage participation.

- Consultation: it has a minimum duration of 30 days. In this phase, public meetings are held and, according to the methods established by the administration, the contributions of each interested party are organized. Following an assessment of technical feasibility, the collected contributions are therefore submitted to the evaluation of citizenship that can be expressed by means of a voting card with a single preference. Subsequently, a participation document is planned to be prepared by the relevant town department. This will be forwarded to the council for the appropriate assessments. Lastly, it will be taken into account in the budget proposal.

- Monitoring: this step is aimed at guaranteeing to all interested parties the possibility of verifying the effects produced by the presented contributions, highlighting the general evaluations with reference to the advanced proposals. To this end, the administration facilitates access to documents and procedures, ensuring transparency, dialog, and efficiency. All data and information relating to the participation process, including the outcome of the submitted contributions, as well as the changes made to the deeds during the entire process, are made available on the municipality's website (Comune di Casamarciano, 2018).

5.3 Voting shares

With regard to population, the work exploits the demographic projections provided by the Brazilian and the Italian national statistics institutes. Data from the municipalities of Porto Alegre, Brazil, is used for examining the amount of voting. Data gathered from the field were collected to detect the voting shares in Casamarciano, Italy. Data from the national statistics institutes of Brazil and Italy are convened to explore comparatively the demographic trends of the two cities.

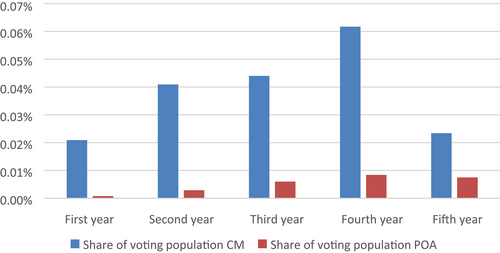

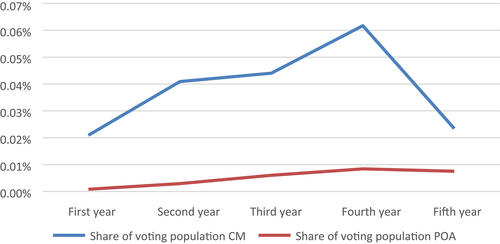

It is possible to appreciate interesting figures concerning CM performance on voting. During the first 5 years of the project implementation, CM citizens who voted were, respectively, 0.0209% in the first year, 0.0409% in the second year, 0.0440% in the third year, 0.0617% in the fourth year, and 0.0234% in the fifth year (Comune di Casamarciano, 2018). As we can observe in Table 1 and Figures 1 and 2 below, throughout the 5 years, the rate of the population involved in Casamarciano in the PB process was comparatively high with respect to international evidence and tangibly larger than the Porto Alegre rate for the first 5 years of PB (Comune di Casamarciano, 2018; IBGE, 2010; ISTAT, 2018; Prefeitura de Porto Alegre, 2013).

| Year | First year (%) | Second year (%) | Third year (%) | Fourth year (%) | Fifth year (%) |

| Share of voting population CM | 0.0209 | 0.0409 | 0.0440 | 0.0617 | 0.0234 |

| Share of voting population POA | 0.0008 | 0.0029 | 0.0060 | 0.0084 | 0.0075 |

- Abbreviations: CM, Casamarciano; PB, participatory budgeting; POA, Porto Alegre.

In Table 1, the yearly shares of voting of the first 5 years of PB implementation are provided. These data refer to both CM and POA-involved populations. The comparison between the two cities engagement rates is also graphically sketched—Figure 1. Figure 2 presents a plotting of the trends of voting population for the two examined cities.

A caveat shall be flagged. The sorting outcomes shall be evaluated for the specific case study analyzed. The results can be regarded as an exploratory analysis for future investigations. Conversely, the figures shall not be reputed as leading forces for inferring an inverse causality with corruption rates or as a policy or governance indicator. Corruption, policy, and governance effectiveness shall, indeed, be considered and specifically assessed making use of selected techniques (Agovino et al., 2018; Busato & Gatto, 2019; Gatto et al., 2021; Sadik-Zada & Gatto, 2021). This intriguing goal is, however, out of this inquiry's scope.

More broadly, PB shall not be confused with primary policy actions, having different sorts of impact. Similarly, PB shall not be conceived as an all-encompassing panacea. On top of that, the possibility for PB to overlooking the poorest socioeconomic groups according to the modeled design shall be pointed out (Saguin, 2018).

PB—and more broadly participative democracy—are under no circumstances tout-court remedies to the vices of representative democracy and are no guarantees for the risk of reproducing the same corruption dynamics. This occurrence is particularly frequent and recurrent in countries that are heavily affected by corruption (Sargiacomo et al., 2015). PB and participative democracy instruments shall be contemplated as viable channels to foster citizens' participation and empowerment. PB can also be a contributing factor in increasing the attention on transparency and democracy—which can possibly lead to easing corruption.

6 CONCLUSIONS

This article explored the role of PB as a tool to address institutional corruption and transparency problems, capable to implement good governance, citizens' participation, and long-standing development. PB promises to lead to enhanced participation among the citizens contributing to better addressing policymaking and local development.

This work clarified a specific feature of PB—voting shares—along with corruption. This item has been explored within the development, public affairs, and governance debate. For this scope, on field research has been exploited, making use of mixed methods and a case study. The work analyzed four sets of data—ISTAT, municipal, and field data. This gave the possibility to mix different methods, corroborating the investigation. On top of that, the combination of census, voting, and project's features data are jointly exploited for the first time, presenting an added value of this work.

The inquiry found that the initial figures from the case study of Casamarciano municipality in Campania rendered significant results in terms of both participation and strategy. These outcomes allow being confident with the model's performance. The figures are quite interesting even when compared to the most notable benchmark PB experience—that is Porto Alegre, Brazil.

The outcomes may allow research and practical applications. Development, public affairs, and management scholarship may acquire fresh information and insights from a set of novelties—that is, the theoretical framework, case study, methodology, and results implications. Practitioners in both development, public management, business, administration, and policymaking may get new ideas to be implanted in their programs. The civil society may be interested in getting some news of the world on PB, perhaps attempting to implement some of the procedures in their hometown. Additionally, PB may reply to the open call for providing the organization with both increased substantial control and adaptation to the local environment (Caputo & Di Cagno, 2010). As an innovative management instrument, PB can, indeed, assist the (public) administrations, institutions, and organizations in monitoring, controlling, and auditing processes. These steps are crucial to an urgent sustainability transition within the corporate administration and goals. Firms are, nowadays, required to overcome the mere financial objective, striving to reach wider rethinking of the socioeconomic, governance, and environmental results (Caputo & Di Cagno, 2010; Gatto, 2020).

Different studies have investigated PB in Italy. Nevertheless, to date, none of the inquiries has highlighted the good practice of Casamarciano, focusing on voting aspects. However, the study at hand is not exempt from drawbacks. Casamarciano is just a small town and does not reach the population size that characterizes Porto Alegre—a large city. Though it shall be remarked that, albeit demographics data are easily reachable, the same feature does not always apply to data on the share of the voting population. In addition to this, the inquiry deliberately aimed to compare the results of a small municipality lacking tools and funds in contrast to a decisively larger and glaring global successful benchmark. The objective was to highlight the goodness of the former town policies in involving less educated citizens, collating them with a metropolis' citizenship.

Another possible weakness of the study at hand concerns the analyzed years for the two cities. In fact, the contemplated periods cannot match entirely, considering that the projects were launched in different years. This means that trends, expectations, and socioeconomic facts may diverge—in those years the world has been going through changes. Nonetheless, it was preferred to yield priority to a fully comparative analysis, capturing the same years of the project's implementation instead—namely, the first five operational years. This information can render insightful indications relatively to public management success and failure. Future studies may want to analyze these aspects through one of the mentioned alternative perspectives. Alternatively, prospective works might be stressing a variety of different foci—for example, voters' preferences.

Porto Alegre is the most renowned case in both the scientific literature, public management and affairs, and political ambients. The Brazilian city pioneered the implementation of PB, successfully involving part of its population in the decision-making. Many municipalities followed this case study, both in OECD and non-OECD countries. This study analyzed the municipality of Casamarciano, a small town in the Province of Naples. Casamarciano administration launched the PB in 2012, involving its population into 10% of the public budget.

Field interviews returned important insights on the pursued PB model promoted in CM. Specific public affairs dynamics and public management strategies to implement the local PB have stemmed from fieldwork. Regardless of the town's reduced size, the local administration of PB had clear ideas on the strategies to be carried forward. It also emerged an enthralling and long-sighted management perspective when it comes to the topics to be voted. Above all, topics related to sustainability were quite insightful, especially if one stresses the population's size and the local inhabitants' composition—where the voters, in fact, are usually devoted to simple jobs in a quasi-rural village.

Along with the qualitative strategy preferences, the investigation gathered quantitative data on the voting shares. The voting outcomes have been collated with possible alternatives and the overall world's participation. In fact, besides the qualitative detailed information on the PB practice of CM, field research has generated quantitative data on the shares of the voting population in CM PB over the first 5 years of the project's implementation. The sharing voting population were analyzed for both Porto Alegre and Casamarciano. The study discovers that the share of citizens involved was 4–50 times bigger in the small Campania town. The involved population is a major issue when it comes to voting and a usual indicator of the success and the impact and usefulness of the exercise. Tailored policies may enhance the share of the voting population. This is the case of “getting out the vote” campaigns, which positive effect has been scrutinized even for PB and POA (Peixoto et al., 2020).

PB is a relevant development topic that needs case studies explorations to detect revised models and configurations (Lerner, 2017). PB must be framed into a wider conceptualization of rethinking the transparency and participation of public and private administrations. In a context of amplified needs in accounting and public affairs, PB arises as a new bottom-up solution, valuable for democratization purposes (Kersting et al., 2016). Public administrations shall, indeed, be conceived as organizations, obeying the same economic rules of firms (Caputo & Di Cagno, 2010). The examined case study demonstrated that this tool could help to influence long-term planning in addressing governance and development, with special regard to low-income regions, affected by high rates of corruption and low rates of transparency. Nevertheless, PB potential shall be confined to its limited range and highlights a glaring limitation of this tool.

Corruption is a recurring, enduring figure in Italy (Del Monte & Papagni, 2001). It is, indeed, harder to sort it for countries experiencing structural governance problems and high rates of corruption within politicians and bureaucrats ambients—those deputed to model the regulatory framework and having strong influence and power (Sargiacomo et al., 2015). In this sense, possible strong motivation for public management modeling and investments shall not surge as showcasing transparency, anti-corruption, and sustainable development plea, risking to become infamous ineffective propaganda instruments.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENT

The authors would like to thank the editors Phil Harris, Fabio Caputo and Aviral Tiwari and two anonymous referees for their kind support.

Biographies

Prof. Andrea Gatto is Senior Assistant Professor at Wenzhou-Kean University (US-China). He is Visiting Research Fellow and Lecturer at the Natural Resources Institute (NRI), the University of Greenwich. Dr. Gatto has got a publication record in international peer-reviewed journals – including Energy Policy, Journal of Cleaner Production, Ecological Economics, Journal of Environmental Management, Corporate Social Responsibility and Environmental Management, Energy Research & Social Science and Journal of International Development. An economic and business consultant, Andrea is President of the CED – Center for Economic Development & Social Change and is Deputy Director and Fellow at the Centre for Studies on the European Economy at UNEC. Andrea sits on several international peer-reviewed journals' editorial boards (Q1-Q2). He has conducted fieldwork and worked for longer appointments in twelve countries worldwide, including positions for the European Commission, CalPoly, CREATES – Aarhus University and the NCH at Northeastern University. He is fluent in Italian, English, French, and Portuguese, and speaks some Spanish.

Dr. Elkhan Richard Sadik-Zada, Dipl.-Ök. is a development and resource economist with a graduate diploma and PhD from Ruhr-University of Bochum, Germany. Since 2011 he works as a postdoctoral research fellow at the Institute of Development Research and Development Policy at Ruhr-University of Bochum. Between 2017 and 2018 Dr. Sadik-Zada worked as an official invited visiting scholar at the Faculty of Economics of the University of Cambridge. 2019 he joined Center for Environmental Management, Resources and Energy (CURE) at Ruhr-University of Bochum. He is a distinguished honorary member of CED - Center for Economic Development and Social Change in Naples, Italy. He published in Socio-Economic Planning Sciences, Atlantic Economic Journal, Mineral Economics, The European Journal of Development Research, Post-Communist Economies, Review of Development Economics etc.

Open Research

DATA AVAILABILITY STATEMENT

Data will be made available upon request.