Linking political brand image and voter perception in India: A political market orientation approach

Abstract

Political parties in order to design their competitive strategies are always keen to understand the factors that govern voter's perception. Voter's perception in this paper utilizes voter's acknowledgement of voter orientation (VO) of political parties. The purpose of this paper is to examine the constituent variables and their cumulative impact on voter's orientation and examine the linkage that exists between them. The authors have proposed four key constructs that demonstrates causality namely voter involvement (VI), voter subjective knowledge (VSK), political brand image (PBI) and environmental factor (EF). The study has used SEM method of model estimation. VI and VSK merged into a new construct labelled as voter engagement (VE). Engaged voter would impact PBI positively and political brand impacts VO. The relationship of VE and VO is mediated PBI, but the same kind of mediation is not witnessed in the case of EF. This research advances the understanding of composite variables of VO from the vantage of political market orientation. Political brand mediates the association between VE and voter perception.

1 INTRODUCTION

Political marketing has evolved over the decades as a sub-discipline of marketing in several trajectories (Harris & Lock, 2010; Schofield & Reeves, 2015). In a marked departure from the past, political marketing has included the term “stakeholder” (Hughes & Dann, 2009; Ormrod, 2017) and that each exchange of value in the political context constitutes interactions (Henneberg & Ormrod, 2013). One of the emerging dimensions of research has been applying consumer behaviour theories to voting behaviour (Cwalina et al., 2010; Newman, 1999, 2002; Newman & Sheth, 1985; French & Smith, 2010). These studies highlight voters' belief about media's role in elections, cognitive domains, and feelings, with all the three elements influencing voters' attitude towards the candidate. More specifically, Ben-Ur and Newman (2010) posit six distinct cognitive domains that drive voter's behaviour. Similarly, O'Cass and Pecotich (2005) explored the impact of cognitive domains used in consumer behaviour on voter behaviour during elections. Further, voter behaviour is an outcome of political branding decisions and political brand image (PBI). The importance of political brand and its sensitivity to voter behaviour has been stated by Scammell (2007) and Ahmed et al. (2017) through the PBE framework and recommends integrating political brands in voter's choice. The role of PBI has been used to explain the bond between political parties, voters and leaders during post-election times (Jain et al., 2017). French and Smith (2010) affirm that political brands and their collective memories are likely to influence voter behaviour, thus affecting the outcome of the general election. There is enough conclusive evidence to explore the influence of PBI in shaping voter orientation (VO), a gap that is addressed in this paper. Despite being in the tradition of attempting to understand voter behaviour, this study is independent of election or pre-election campaign, hence may demonstrate the true reflection of the way voters acknowledge political party's VO in general. The political systems of non-Western democracies typically comprise several political parties that are well entrenched and pervasive than those in the developed democratic systems (Bittner, 2008). At the same time, non-Western countries offer new ideas for democratic innovation (Youngs, 2015), and democracy supporters from the West may find some takeaways from these democratic models. It will be interesting to uncover the interrelationship among the myriad of factors affecting voter behaviour. Voters need to know if the party understands and acknowledges their needs and wants, manifested as VO (Ormrod, 2005). Understanding voter behaviour becomes imperative for a genuinely voter-oriented party. Further, this research seeks to explore the role political brand plays in shaping VO.

1.1 Political marketing orientation

Market orientation is an organisation-wide responsibility towards listening and responding to the latent and manifest needs and wants of the various actors in society (Narver et al., 1998, 2004; Slater & Narver, 1998). Despite the literature's focus on the holistic nature of an organisation's market orientation, political market orientation has a specific voter-oriented view (Ormrod & Henneberg, 2010). Literature shows that orientations of various categories of stakeholders characterise attitudinal antecedents that drive political market-oriented behaviour. Ormrod and Henneberg (2010) offered different stakeholders such as voters, competing parties, media, and internal members to be constituting the party's attitudinal constructs that drive political marketing orientation (PMO) behaviour.

Ormrod (2005) conceptualised that VO is defined as party-wide awareness of voter needs and wants and acknowledging the importance of knowing these. Indeed, a voter-oriented party will satisfy the articulated and not-so-well articulated needs and wants of the target voter groups (O'Cass & Pecotich, 2005; Strömbäck, 2007). Advances in the theoretical foundations of political marketing were integrated with Ormrod's (2005, 2013) conceptual model of PMO to propose a revised conceptualisation of a political stakeholder orientation (PSO) (Ormrod, 2020a). Newman (1999) models several cognitive and conative domains to explain voter behaviour. Thus, understanding voters' perception of whether parties are truly voter-oriented or not calls for academic and practitioner inquiries (Ormrod & Savigny, 2012). The authors in this paper are partially extending the utility of PMO by operationalising the framework among primary stakeholder, that is, the voter, to assess their perception levels. An effort has been made to understand if voters truly reciprocate the VO posture of the parties, done with suitable modification of the VO construct with the help of political scientists. It may be concluded that there is a dearth of research that aims to look at the PMO of the political parties but from a voter's vantage point. This paper is situated at this location. While it observes the PMO of Indian political parties through the VO lens, it further explores the mediation effect of PBI on PMO. An attempt has been made to understand the extent of universality and generalisability of core political marketing concepts, viz. PMO and VO, in non-Western markets and cross-cultural settings (Harris & Lock, 2010).

1.2 New settings and contexts

India has been proclaimed a strong case of 'deviant democracy' (McMillan, 2008) for its exceptional democratic transition and consolidation after the British colonial rule. Deviant cases help us understand why some countries have maintained democracy for an extended period, whereas other countries have moved to authoritarian rule after democratic transition (Seeberg, 2014). In a deviant democracy like India, the role of political parties, their market orientation and the way voters have responded could be an interesting area of investigation. Vanhanen's (1997) method of testing democratisation found India far more democratic than expected. Despite the size, diversity, religious, linguistic, and social cleavages being obstacles to explaining successful democratisation, comparative studies of ethnolinguistic fractionalisation place India at the highest end of the scale (Manor, 1990). A combination of dimensions like clientelism, post clientelism, identity politics, developmental politics and political entrepreneurship is unique to India and similar political systems when compared with Western democracies. Indian elections have been dominated mainly by caste and identity-based politics, both positive and negative (Suri et al., 2016). Caste has increasingly become a dominant factor in Indian elections, forcing parties to enhance the 'saleability' of a broad-based appeal. Rising non-Western democracies may be better positioned than their Western counterparts to support democratic variation (Youngs, 2015). It would be interesting to study how political parties collect and operationalise voter insights into actionable strategies in the new democratic models. There is a problem related to the mapping of deviant democracies and isolating realistic explanations of the 'deviancy' phenomenon (Doorenspleet, 2017). Among the factors that explain deviant democracy, level of modernization, and degree of democracy in neighbouring countries are critical (Seeberg, 2014). Since good marketing practices improve the political process and, in turn, that of democracy (Quelch & Jocz, 2008), it would be interesting to probe, among other factors, to what extent political parties in deviant democracies follow market orientation or stakeholder orientation approach.

There is a key transition from the early days of Indian politics, where the ideologies of the major parties were enough in drawing the notice of the electorate (Banerjee & Chaudhuri, 2016). Centre of Media Studies estimated that Rs 50,000 crore (USD 7 billion) was spent during India's General Elections in 2019, a 40% jump from the Rs 35,000 crore (USD 5 billion) spent during the previous polls in 2014 (The Economic Times, 8 May, 2019). Political campaigns in India usually extend over several months, and every political strategist has a different approach to creating one for their candidate. Generally, the strategists offer end-to-end services starting from elections surveys, political strategy and management, analytics and political intelligence, campaign management, political advisory services, digital media management, etc. It is believed that they keep their ears to the ground and devise the strategies with an expectation that a positive impact on the fate of the political parties can be created. A politician or a political party start work 5–6 months ahead of the elections. All marketing actions in politics depend on a particular country's political system and its components (Cwalina et al., 2011). In the case of India, such studies are at best scarce or absent. Still, those issues assume a lot of importance in democracies like India, where vast sums of money are spent on marketing by major political parties (Banerjee & Chaudhuri, 2016). However, the question that remains uppermost in researchers' minds is whether the parties use the information collected to comprehend the electorate's moods strategically. The bigger question is, are the activities and behaviours of the organisation aligned towards achieving market orientation? Is there a sporadic rise in implementing marketing concepts in poll campaigning without a strategic consideration to market orientation?

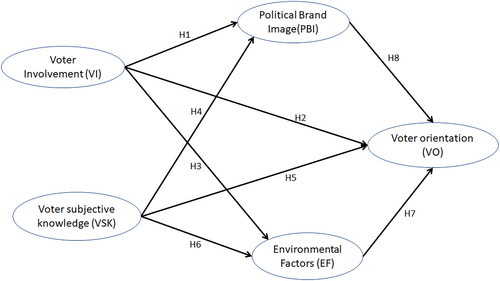

Further, such knowledge and management of constituent variables will enable political parties to create favourable disposition among their voter bases. The proposed framework probes the impact of voter involvement (VI) and voter perceived subjective knowledge (VSK) on VO, mediated by PBI and environmental factors (EF). The study posits that voter engagement (VE) (a composite construct formed from VI and voter perceived subjective knowledge) unambiguously influences VO.

This paper is structured by delving into the extant literature for each construct under discussion. The methodology adopted is described in the subsequent section, followed by the results and discussions. The concluding remarks follow along with the managerial implications of the study. Finally, the article ends with its limitations and possible future research avenues.

1.3 Conceptual framework

1.3.1 Voter orientation

Voters are essential stakeholders in a political exchange and are implicitly or explicitly posited as the central rationale for political marketing (Butler & Collins, 1994; Harrop, 1990; Newman, 1994, 2002; O'Shaughnessy, 1990; Scammell, 1999). VO is the reflection of customer orientation into the realm of political marketing (Ormrod, 2005). Parties that are voter-oriented will accord importance to the voters' opinions to build up an understanding of the voter behaviour. The VO construct explains the attitudes of all party members towards being aware of the individual voters' needs and wants, member's willingness to enter a social exchange and unravelling voter opinions at the party level (Ormrod, 2005). VO is the central dimension in political marketing (e.g., Butler & Collins, 1994, 1996; Dean & Croft, 2001). Political parties in UK with similar PMO levels demonstrate high degree of VO and external orientation (Ormrod & Henneberg, 2009). Contrarily, Ormrod and Henneberg (2010) demonstrates the diminishing effect of the VO construct on the PMO of parties hinting at the non-voting electorate who are affected by public policy decisions of political actors.

Consequently, VO's predictive power is getting diminished and hence the need for bringing in other stakeholders, leading to the emergence of the stakeholder theory as a supplement to the PMO model. While all stakeholders are critical to the political actor from a normative perspective, swing voters in marginal seats are strategically essential for success in the electoral marketplace (Harris, 2001;Henneberg & Ormrod 2013). This extension into PSO model considers a 'prioritised' approach to the stakeholders while being more' context specific' (Ormrod, 2020b). This paper attempts to understand the way voters acknowledge different party's VO, which in turn reflect voters' actual voting behaviour. Understanding voter behaviour through VO in a non-Western and deviant democracy has not been studied so far.

1.3.2 Voter involvement

VI is an indicator of the degree of importance that the voter associates with the electoral process and, therefore, reflects voters' active engagement during the election of their political representatives (O'Cass, 2000, 2002). Earlier studies have suggested that high VI enables voters to judiciously evaluate the performance of political parties and make informed election decisions in the process (Geys et al., 2010; Richins & Bloch, 1991). Among young voters, understanding their desires and interests is crucial to engage them in the political process (Manning, 2010; Winchester et al., 2016). It has already been established that the greater a consumer's involvement in an object, the greater her propensity to engage in information search (Beatty & Smith, 1987; Winchester et al., 2016). Kirmani et al., (2020) have opined that political knowledge is expected to sensitise voters towards prevailing issues and encourage them to participate in politics. VI, going beyond electorate turnout, has well been regarded as a measure of citizen involvement (as Borge et al., 2008). There is abundant evidence of political researchers utilising the construct—involvement—to assess voters' involvement in politics, elections, political issues and political advertising (Burton & Netemeyer, 1992; Campbell et al., 1980; O'Cass, 2002). Political brands gain their strength from the higher involvement of voters (Smith & French, 2009). Therefore, involvement will significantly affect PBI. As (O'Cass & Pecotich, 2005) linked VI with subjective knowledge, authors believe that higher levels of involvement will enable voters with higher discernability of EF.

H1.Voter's higher involvement in politics will have a significant positive influence to shape PBI in voter's mind.

H2.Voter's higher involvement in politics will have significant positive influence to shape political party's VO in voter's mind.

H3.Voter's higher involvement in politics will have significant positive influence to shape knowledge of EF in voter's mind.

1.3.3 Voter subjective knowledge

VSK has been adapted to the political context (Winchester et al., 2014). The meta-analysis carried out by Fernandes et al. (2014) establishes an important distinction between objective knowledge (OK) and subjective knowledge (SK). For example, a voter recognising a political party's vision to be 'welfare centric' is objective, whereas the feeling that he/she understands politics is a manifestation of subjective knowledge. (O'Cass & Pecotich, 2005) demonstrated the role of subjective knowledge in enhancing voter choice related to political parties, politicians, and degree of satisfaction with politics, which enables us to conceptualise the influence of subjective knowledge on PBI. Voters remember, or at least recognise, established political leaders over unknown ones is evidence of that (Jacobson & Carson, 2016). Literature shows that subjective knowledge affects the entire decision-making process, from attribute selection through search to perceived outcomes (Raju et al., 2015). Therefore, it may be reasonable to believe that a well-decisioned voter can evaluate whether political parties intend to understand their needs, wants and acknowledge this while formulating political strategies. Our hypotheses are as follows:

H4.Voter's higher subjective knowledge will have significant positive influence to shape PBI in voter's mind.

H5.Voter's higher subjective knowledge will have significant positive influence to shape political party's VO in voter's mind.

H6.Voter's higher subjective knowledge will have significant positive influence to shape knowledge of EF in voter's mind.

1.3.4 Environmental factor

Political marketing theory has been broadened by triadic interaction structure of the political exchange (Henneberg & Ormrod, 2013)—the interactions being (i) the electoral marketplace (between the political actor and voters), (ii) the parliamentary marketplace (between the political actor and other elected politicians), and (iii) the governmental marketplace (between the government and citizens). Elected political actors cannot create value for voters unless they influence coalition partners to formulate and implement legislation. Such efforts are affected by EF such as international legislation and macroeconomic conditions. Ormrod (2017) elaborates EF as socio-economic factors/stakeholders that do not directly contribute to the abovementioned interactions but impact the voter. Such factors will include competitor marketplace, mass media, social media, interest and lobby groups. This is particularly true in India, where politics revolve around issues related to underprivileged sections of society, among other issues. The new-age Indian voters are aware of these issues and demand better status for disadvantaged sections in the society and hence, expect the political party they vote for should work towards empowering these people (Kalokhe et al., 2017). Relationship between VSK and VO is mediated by EF, which gets reflected in the proposed H6. A voter with high VSK will achieve greater clarity on the EF ranging from legal, social, or economic. With a broader time horizon, EF sufficiently moulds voters' attitude about political parties (Smith, 2001). The construct, EF, has been adopted from (Newman & Sheth, 1985) by merging 'issues and policies' with 'current events' and modified to the Indian political environment based on observations of political science experts. 'Issues and policies' constitute the perceived value the candidate/party possesses on economic policy, foreign policy, social policy and leadership characteristics. On the other hand, 'current events' refers to contemporary domestic and international situations which would cause the voter to switch her vote to another party. The proposed model hypothesises that subjective knowledge will impact a voter's disposition towards EF and determine her understanding of the party's VO. This finds validation in Smith and French (2011), who state that voters' interpretation of new information will affect their attitude towards political parties. Although subjective knowledge has been linked with voter's choice (O'Cass & Pecotich, 2005), this paper fills the gap as to how subjective knowledge combined with EF determines voter's understanding of the party's VO. As a result, the hypothesis is as follows:

H7.Voter's higher knowledge of EF will have significant positive influence to shape political party's VO in voter's mind.

1.3.5 Political brand image

PBI bridges the political parties to the voters in a way similar to the realm of consumer brands. Ormrod's (2005) conceptual model of market orientation states that success of the party tends to reside on the party's brand and its management. It is the voter's association with the brand that makes them 'own' the political brand. The voter is considered a cognitive miser with no desire to process large quantities of political information, analyse the merits of policy interventions, or follow day-to-day news. She collects selective information that helps her form an attitude towards the political parties, achieved through a strategic formulation of the PBI (Winther Nielsen, 2015). Just as brand image is critical in creating customer value, similarly, PBI provides value to the voter by enhancing the interpretation/processing of information about the party and/or voter perception, resulting in increased confidence in the voting decision (Smith, 2001). It also acts as a heuristic for both market orientation (Lees-Marshment, 2001) and political orientation (O'Cass & Voola, 2011) that define a political party.

Political brands have three distinct elements: (i) the party as the brand; (ii) the politician as its tangible characteristics; and (iii) policy as a core service offering (O'Shaughnessy & Henneberg, 2007). Most voters have low involvement with party politics and policies or are disinterested to learn about those. In such cases, the political leader conveys a complex meaning that contributes to creating favourable voter perception (Smith, 2001). The significance of personality traits of politicians is increasingly being perceived by the voters (Gorbaniuk et al., 2015). It appears that a leader/candidate transfers his/her associations to the party brand. For example, the appointment of David Cameron as leader coincided with the Conservative Party's improved popularity (French & Smith, 2010). Political marketing tools solidify the bond between voters and parties, attributed to political brand management (Jain et al., 2017). Dean (2014) emphasise the importance of examining brand building as an ongoing relationship-building process, rather than just a narrow election-winning activity. Falkowski and Jabłonska (2020) analysed the moderating role of candidate perception and voting intention. They suggested that candidate image can improve voting intention for the candidate as long as messages, policies and campaigns are relevant and appealing to voters. Grynaviski (2010) says symbols are commodities that provide politicians with a cost-efficient mechanism to signify their value to voters. This is why most candidates and parties are preoccupied with building their brands and personalising their candidature with imagery of capability, character, and trustworthiness (Pich and Dean, 2015). Here, the resilience of the individual or party brand has a direct impact upon reputation and trust (Dermody and Hanmer-Lloyd, 2004), which in turn, has an enduring effect on voting intentions. Focusing on young voters, Susila et al. (2020) explore how symbolic communication that is created and expressed by politicians and government and assess how it relates to the acceptance and engagement with political brands.

There is considerable evidence supporting the mediating role of PBI in bringing out voter intention, voter perception, voter turnout irrespective of election timing. Further, strong political brands result from high VI, reiterating a strong relationship between VI and PBI. This paper models the association of VI and VSK with VO largely explained by the mediation of PBI (Baines et al., 1999; Chou, 2014; French & Smith, 2010; Jain et al., 2017; Kotler, 1999). Hence,

H8.Higher PBI in voters mind will have significant positive influence to shape political party's VO in voter's mind.

Based on the above hypothesis, the theoretical model proposed is represented in Figure 1.

1.4 Methodology: Measures

The study is built on existing literature on the influence of VI and VSK on VO. PBI and EF mediate these relationships. The four independent and the only dependent variable were all measured through a single scale. The scale was generated by combining two established scales (Newman & Sheth, 1985; O'Cass & Pecotich, 2005). In both cases, voter behaviour has been studied. Newman and Sheth (1985) develop a basic model for voter behaviour, whereas O'Cass and Pecotich (2005) look at it from a consumer behaviour vantage. Personal events in the candidates' lives (political or marital/romantic scandal, etc.) were considered superficial and were excluded in favour of the more important political and economic issues (Funk, 1996). Moreover, such incidents are more instantaneous and have more significant impacts closer to the elections (Bhatti et al., 2013).

Voter responses were collected in 2017, exactly between two consecutive general elections of 2014 and 2019. It can be assumed that there was no major post or pre-election effects, which eliminated any possibility of influencing voter response. Our proposition that voter perception was independent of any pre-campaign or in-campaign marketing intervention gets corroborated. It was an unbiased expression of voter perception that could be shaped with the help of PBI and other EF (Smith & Speed, 2011).

We added two items to make it a 28-item 4-point Likert scale. A 4-point scale makes the respondent express a decision, take a non-committal position, and not opt for the middle neutral one (Bishop, 1987). Three university professors of Political Science checked the scale for content validity. The minor changes suggested by the experts were incorporated, and the scale was finalised. We used a 4-point Likert scale by removing the neutral point to compel the respondent into taking a specific stance. Researchers in diverse fields have questioned the utility of the middle category in a Likert scale as it does not provide any useful information to the researcher (Kulas & Stachowski, 2009; Willits et al., 2016). Neither does it specify the respondent's position, whether it is lack of opinion, indifference, lack of understanding or a perfectly balanced opinion. Croasmun and Ostrom (2011) also assert that the middle point provides the respondents with an option for indecisiveness or neutrality, which people without an opinion would conveniently choose.

1.5 Data collection

The data was collected through judgmental sampling as there were specific criteria that the members of the sampling frame had to meet to qualify as respondents (Mureşan et al., 2015). We collected 296 completed questionnaires from Indian citizens aged between 18 and 31 and residing in the states of Odisha, West Bengal, and Madhya Pradesh. They represented different parts of the country, so the demographic variation was maintained among the respondents. We focused on the said age group to target voters who had voted once or at the most twice. The young voter is accorded importance in political debate and political marketing because this demographic group is perceived to be politically aware but is disengaged at the same time (Pich et al., 2018). The lack of integration of young voters is regarded as a weakness of a political system (Dermody et al., 2010; Leppäniemi et al., 2010; Winchester et al., 2016).

The average time taken by the respondents to complete the survey questionnaire, including the demographic items, was 5.27 min.

2 RESULTS

The variables were analysed for reliability in SPSS 20. The results for reliability, as given by Cronbach's α, are summarised in Table 1.

| Variable | No. of items (initial) | No. of items (after reliability check) | Reliability |

|---|---|---|---|

| Voter involvement (VI) | 6 | 5 | 0.880 |

| Voter's subject knowledge (VSK) | 4 | 3 | 0.874 |

| Political brand image (PBI) | 8 | 8 | 0.966 |

| Environmental factors (EF) | 5 | 3 | 0.821 |

| Voter orientation (VO) | 5 | 5 | 0.706 |

This was followed by factor analysis of the independent variables. The 19 items designed to capture the four variables were subjected to exploratory factor analysis with Varimax rotation. The factor analysis results are presented in Table 2, with 72.24% of the variance being explained by the items.

| Factors | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 2 | 3 | |

| VI1 | 0.802 | ||

| VI2 | 0.346 | 0.728 | |

| VI3 | 0.726 | ||

| VI4 | 0.791 | ||

| VI5 | 0.780 | ||

| VSK1 | 0.769 | ||

| VSK3 | 0.788 | ||

| VSK4 | 0.740 | ||

| EF1 | 0.851 | ||

| EF2 | 0.905 | ||

| EF3 | 0.792 | ||

| PBI 1 | 0.895 | ||

| PBI 2 | 0.925 | ||

| PBI 3 | 0.917 | ||

| PBI 4 | 0.919 | ||

| PBI 5 | 0.890 | ||

| PBI 6 | 0.894 | ||

| PBI 7 | 0.851 | ||

| CI8 | 0.865 | ||

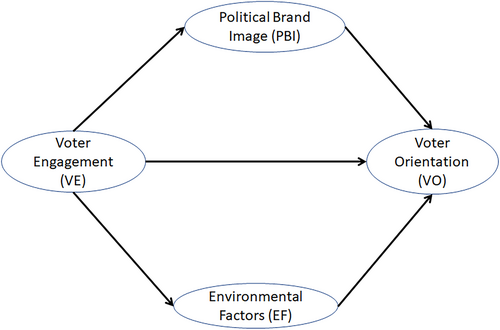

It is quite evident from Table 2 that the items belonging to EF and PBI have converged nicely into the respective factors. In contrast, the items of VI and VSK have merged into a single factor, thus ending up with three factors instead of the original four. The factor formed by the merging of VI and VSK was named VE since the involvement of the voter about the politics, and the extent of her knowledge about the political issues give a clear sense of how much captivated the voter is in the political realm around her (Figure 2). We consider VE as an intrinsic behaviour of the voter. It does not incorporate VE (similar to customer engagement) actions from the side of the political party. As a result, the merging does not alter the fundamental alignment of the earlier constructs.

We also carried out factor analysis for the items belonging to the dependent variable, VO. Again, the numbers point out that the items converge into a single factor (Table 3).

| Factor | |

|---|---|

| 1 | |

| VO1 | 0.643 |

| VO2 | 0.706 |

| VO3 | 0.736 |

| VO4 | 0.655 |

| VO5 | 0.648 |

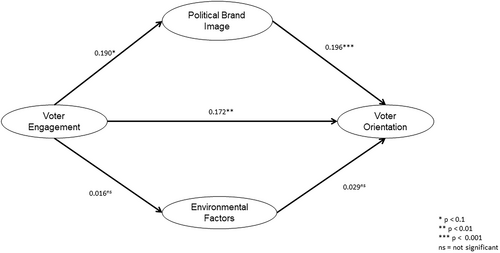

In the next stage of the analysis, we conducted SEM between the variables to understand how VE, PBI and EF affect VP. This was carried out in AMOS 18. The results (Table 4) and the path diagram (Figure 3) of the analysis are given below. From the SEM results and the path diagram, VE has a positive influence on VO. Also, the PBI does seem to mediate this association. However, no conclusion can be drawn regarding the mediating influence of EF on this association since both the paths show statistically not significant results (Tables 5–8).

| Relationships | Standardised regression coefficient | C.R. | Significance |

|---|---|---|---|

| VE → PBI | 0.190 | 1.635 | 0.100 |

| VE → EF | 0.016 | 0.203 | ns |

| VE → VO | 0.172 | 3.191 | 0.001 |

| PBI → VO | 0.196 | 4.771 | *** |

| EF → VO | 0.029 | 0.712 | ns |

| Fit indices |

- Note: χ2 = 773.39; df = 247; p < 0.001; CFI = 0.873; NFI = 0.826; RMSEA = 0.083; TLI = 0.846.

| Estimate | S.E. | C.R. | P | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Voter engagement → VE1 | 1 | |||

| Voter engagement → VE2 | 0.881 | 0.075 | 11.786 | *** |

| Voter engagement → VE3 | 0.822 | 0.072 | 11.353 | *** |

| Voter engagement → VE4 | 0.949 | 0.075 | 12.569 | *** |

| Voter engagement → VE5 | 1.033 | 0.081 | 12.695 | *** |

| Voter engagement → VE6 | 0.848 | 0.074 | 11.42 | *** |

| Voter engagement → VE7 | 0.897 | 0.076 | 11.776 | *** |

| Voter engagement → VE8 | 0.77 | 0.07 | 10.94 | *** |

| Statistic | Obtained value |

|---|---|

| AVE | 0.53 |

| χ2 | 43.42 (p < 0.001) |

| df | 20 |

| χ2/df | 2.17 |

| CFI | 0.85 |

| NFI | 0.88 |

| RMSEA | 0.07 |

| AIC | 190.93 (default) 288.00 (saturated) 412.21 (independent) |

| Estimate | S.E. | C.R. | P | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Environmental factors → EF1 | 1 | |||

| Environmental factors → EF1 | 1.246 | 0.112 | 11.139 | *** |

| Environmental factors → EF1 | 0.931 | 0.089 | 10.511 | *** |

| Statistic | Obtained value |

|---|---|

| AVE | 0.63 |

| χ2 | 0.577 (p < 0.05) |

| df | 1 |

| χ2/df | 0.577 |

| CFI | 0.98 |

| RMSEA | 0.03 |

| AIC | 16.577 (default) 18.00 (saturated) 293.94 (independent) |

| Estimate | S.E. | C.R. | P | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Political brand image → PB1 | 1 | |||

| Political brand image → PB2 | 1.033 | 0.045 | 23.053 | *** |

| Political brand image → PB3 | 1.061 | 0.046 | 22.871 | *** |

| Political brand image → PB4 | 1.037 | 0.045 | 22.86 | *** |

| Political brand image → PB5 | 0.957 | 0.047 | 20.257 | *** |

| Political brand image → PB6 | 0.922 | 0.046 | 20.107 | *** |

| Political brand image → PB7 | 0.87 | 0.048 | 18.014 | *** |

| Political brand image → PB8 | 0.895 | 0.049 | 18.445 | *** |

| Statistic | Obtained value |

|---|---|

| AVE | 0.78 |

| χ2 | 67.47 (p < 0.001) |

| df | 20 |

| χ2/df | 3.37 |

| CFI | 0.98 |

| NFI | 0.97 |

| RMSEA | 0.09 |

| AIC | 115.47 (default) 388.00 (saturated) 2296.72 (independent) |

| Estimate | S.E. | C.R. | P | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Voter Orientation → VO1 | 1 | |||

| Voter Orientation → VO1 | 1.053 | 0.178 | 5.906 | *** |

| Voter Orientation → VO1 | 1.112 | 0.182 | 6.093 | *** |

| Voter Orientation → VO1 | 0.891 | 0.16 | 5.557 | *** |

| Voter Orientation → VO1 | 0.953 | 0.176 | 5.43 | *** |

| Statistic | Obtained value |

|---|---|

| AVE | 0.57 |

| χ2 | 22.68 (p < 0.001) |

| df | 5 |

| χ2/df | 4.54 |

| CFI | 0.88 |

| NFI | 0.86 |

| RMSEA | 0.08 |

| AIC | 52.68 (default) 140.00 (saturated) 274.24 (independent) |

3 DISCUSSIONS

The study examined the relationship between cognitive factors, involvement, subjective knowledge, PBI, EF, and VO. VI and VSK merged into VE. In this study, VE is considered an intrinsic voter behaviour that emanates from the voter and not an operationally managed construct by the political party. Fundamentally, it is different from customer engagement and engagement actions firms take to maintain connect with the customers. Based on the results, an engaged voter perceives the political party's performance as improved when assessed against the VO metrics. Zainol et al. (2016) state that the customers' perception about the investments in a brand causes higher levels of engagement, and they will feel a psychological obligation to reciprocate the brand's actions. Engaged voters may experience a similar obligation towards the political party that invests in building its brand image. Highly involved voters reciprocate through communicating brand messages to other voters, particularly at the constituency level (Phipps et al., 2010). The positive strength of the relationship between PBI and VO in this study is backed by Ahmed et al. (2017) findings that state political branding enhances voters' positive attitudes towards a party. This study has made a maiden attempt to understand this relationship from the perspective of the PMO model, primarily VO. Voters evaluate the political brand before making their electoral choice. However, the magnitude of electoral choices depends on the voters' interest, knowledge and involvement in the democratic process.

Customer engagement is the “intensity of an individual's (voter) participation in and connection with an organisation's offerings or organisational activities, which either the customer or the organisation initiates” (Vivek et al., 2012). There is a strong mediation of PBI on VE and VO relationship. The path coefficient between VE and PBI is significant (Figure 3), demonstrating engaged voters will have a favourable perception of the PBI driving VO. Parry-Giles and Hogan (2010) substantiate that governments are made up of people, not issues, and that discussions of PBI are thus 'necessary and valuable' (p. 39). The other mediating construct in our study, EF, subsume the predisposition of the political party towards global and domestic policies. The nature of the environment is determined by interactions from indirect stakeholders in the broader socio-political system. Our submission entails that the involved voter appreciates how political parties adjust to indirect stakeholders, influencing their perception. Thus, EF was expected to mediate the fundamental association as well (Figure 3). The results are statistically non-significant, which points to the probable circumstance that not all the respondents have adequate clarity about the importance of the EF while selecting a political party. Therefore, we posit that majority of the Indian electorate do not perceive the geopolitical and socio-economic issues to be crucial enough to colour the judgement towards a political party. On the other hand, one can possibly interpret that an engaged voter, with her high exposure to political knowledge, is sequestered of EF. This validates the VE and voter perception association (Figure 3).

4 CONCLUSIONS

A gap in political marketing suggests that more focus is needed to understand VO which can be investigated from multiple dimensions. Numerous studies understand complex political brand associations, identity and image, and its impact on voting preference and voting intention (Bennett et al., 2019; Bigi et al., 2016; Pich et al., 2016; Smith & French, 2011). This leaves a wide gap in connecting these with VO. Predicting VO using the PMO framework lends credence and impact to the dependent variable (Ormrod, 2005). In this study, we find that VE and PBI have an unequivocal, positive, and significant influence on how voter-oriented political parties are in India. This study is important because a completely voter-oriented empirical work has not been tried out outside developed democracies. The political systems of non-Western democracies typically exhibit several political parties that are well entrenched and pervasive than those in the developed democratic systems. As a genuine, thoughtful and effective democracy among some 25 meaningful democracies globally, India is worthy of study, encouragement and emulation (Naidu, 2006). Rising non-Western democracies such as Brazil, Chile, India, Indonesia, Japan, Nigeria, South Africa, South Korea, and Turkey certainly offer new ideas for democratic innovation. They may be better positioned than their Western counterparts to support democratic variation (Youngs, 2015). An investigation of the central constructs within the context of different political systems would enhance the applicability and universality of the constructs.

The VE construct was formed out of the convergence of VI and VSK in this work. Purely in a political marketing context, our study helps understand the attitude of the young Indian voter towards the marketing efforts and predispositions of the political parties. The engagement of the voter goes beyond just the behavioural manifestation of voting and encompasses cognitive dimensions of attitude towards parties (van Doorn et al., 2010). The voters have demonstrated that they need to feel comfortable in the process of voting—starting from knowing about the process, engaging in a political debate, understanding the manifestos of parties, making an internal choice of party/candidate, and finally actually casting a vote (Hall et al., 2014). More enhanced and rounded this engagement is, the better is the perception and attitude formation. A strong political brand also synchronises political information, interest, and attention (Bartle & Griffiths, 2002). Its significance is “to reduce the complexity in an environment of proliferating choice and information” (Needham, 2006, p. 184). Thus, brands help the voters connect with the political brand at a functional and emotional level.

4.1 Managerial implications

The contribution of this work lies in its unique integration of the PMO framework with political brand affecting VO, advancing the understanding of voters' perception of political parties and campaign managers. The research provides valuable insight regarding the degree to which voter perception is affected by VE, political brands and political party's disposition towards prevailing 'EF'. Dermody et al. (2010) reveal that “young people are the most disengaged and often feel alienated with politics”; hence, our study tries to find a mechanism to address this through institutionalising VE across digital platforms, which can enhance political interest (Koc-Michalska & Lilleker, 2017). Studies of political engagement do reveal holistic insight into young voters' while they consider engagement across multiple marketing campaigns and channels, offline and online. Social media has evolved as the most popular platform for engaging political discussions (Pich et al., 2018). Further, political campaign managers could segment engaged voters based on the three dimensions cognitive, affective and behavioural profile to improve targeting.

Political actors and public affairs practitioners need to identify the highly engaged voters at the constituency and booth level and mobilise them as 'political mavens', similar to commercial marketing mavens. Micro-level campaigns involving the candidate, and party brand image building can be implemented at the constituency and booth level. These campaigns work well with the efforts of engaged voters in an e-WOM and referral generation (Goldsmith et al., 2006).

The campaigns have to be strengthened with the candidate's image, party ideology or central policy stands taken by the party(s). While evidence of sudden outbursts in campaign activity is quite prevalent, our findings recommend that campaign planners, public affairs practitioners and political strategists desist from a stand-alone and short-term arrangement. And they need to adopt sustainable and consistent communication management, keeping the overall brand strategy in mind. A candidate's electoral programme should be differentiated based on the voter's engagement level. The mediating role of EF in the VE-VO association is not as unequivocal as that of the other mediating construct PBI. The EF needs to be nuanced further using Kirmani et al. (2020) Economic Considerations (EC) and Social Considerations (SC), which can be used to segment voters, and its impact on voter perception can be measured. The role of the environment and external stakeholders on the VE-VO association can precisely capture the mediation effect of EF (Ormrod, 2020a). The study reveals an evident influence of VE on voter perception. However, for a highly engaged voter, the perception will be mediated significantly by PBI (Pich et al., 2016) and less considerably by environmental developments, as revealed in the findings.

4.2 Limitations and future research

As one of the first such studies of its kind, our study has limitations. First, this study is only based on responses from the voters, and the voice of the party is missing. Future studies can investigate reactions from the party members as well. Second, due to the paucity of resources, we could take a snapshot of the voter perceptions on a cross-sectional basis. A longitudinal study across several elections and interim periods can unravel new dimensions into voter psychology. Third, again due to resource constraints, our study was confined to few major cities of the country. The study can be extended to other regions and cities to have a more diverse view of the vistas of a thriving democracy like India. Fourth, the scope of the study may include countries in Asian trade blocs such as ASEAN and SAARC sharing similar political, democratic and economic characteristics as India.

Deeper insights, mined by studying the relationship between engagement and voter perception, will help in deconstructing voter perception at a more granular level. Role of VE and choice of campaign strategy, whether a personality or image-based campaign over issue-based campaign to affect voter perception among low-engaged voters. It remains to be explored whether an issue-based campaign will impact desirable voter perception among high-engaged voters. In addition, the role of EF in voter perception in a deviant democracy can be further investigated.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENT

This paper has been jointly written by both the authors and there is no conflict of interest in considering for review and subsequent publishing if found appropriate. This research project was entirely undertaken by the authors and there is no external funding for the same.

Biographies

Krishna DasGupta is a faculty at XIMB. She teaches CRM and Services Marketing and Marketing Management. Her research area includes customer experience, service consumption and political marketing. She has worked in the pharmaceutical and hospitality industry.

Soumya Sarkar currently teaches at IIM Ranchi. His teaching subjects include B2B marketing, Brand Management and Marketing Management. His research area includes B2B marketing and brand management. His has vast experience of working in the B2B domain.

Open Research

DATA AVAILABILITY STATEMENT

The data that supports the findings of this study are available in the supplementary material of this article.