The effects of hacking events on bitcoin

Abstract

We examine the short-term and long-term effects of hacking events on bitcoin return. Additionally, we attempt to find out if investors can benefit from these events by adopting and modifying the models proposed by Baur et al. (2018) [Journal of International Financial Markets, Institutions & Money, 54, 177–189] who compare the performance of bitcoin against FX returns and the S&P500. The results show that hacking events present an opportunity for investors to make a profit if they invest in bitcoin, stocks and currencies. Such an opportunity, however, does not last for long.

1 INTRODUCTION

As the economy and society become more digital, it is reasonable to argue that digital assets will become more important over time and Bitcoin could be the replacement of gold in such a digital world. One of the best features of bitcoin is its ultimate digital scarcity that becomes even more apparent in light of the substantial monetary expansion in major economies seeking to stimulate the real economy during the Covid-19 pandemic. Bitcoin is viewed as a scarce digital asset in which its value will grow in tandem with its network users who trust and want to hold Bitcoin as a hedge against the monetary expansion diluting the existing stocks of currencies. In a sense, bitcoin is a project or company which is fuelled by the work of all the people in its network and similar to those investors who hold stocks around the globe, bitcoin users and investors are always on the lookout for an increase in bitcoin price.

The pricing of bitcoin (and cryptocurrencies in general) is an issue that has attracted the attention of finance academics and traders who strive to make money out of price volatility. Many studies have examined the determinants of bitcoin price movement or its fundamental value, including Bolt and van Oordt (2016), Li and Wang (2017), Hayes (2017) and Ciaian et al. (2016), Luther and Salter (2017), and Hazlett and Luther (2020). Several other studies investigated the efficiency of the bitcoin market. Cheah et al. (2018), for instance, find that the bitcoin market is fractionally cointegrated and that uncertainty has a negative impact on the cointegration relationship. Furthermore, Chan et al. (2018) examine the usefulness of bitcoin for diversifying risk against the EURO STOXX index, Nikkei, Shanghai A-Share, S&P 500 and the TSX index. By using a pairwise GARCH process on daily, weekly, and monthly return data, they find that the hedging abilities of bitcoin are less significant for daily and weekly data. Another study by Baur et al. (2018) finds that traditional crisis events—such as natural disasters, terrorist events and economic crises—do not affect the price of bitcoin.

We suspect that the price of bitcoin does not follow traditional extreme events, but rather it follows crypto extreme events such as hacking. One of the most important features of bitcoin is its blockchain has a low probability of being hacked. However, this feature does not apply to the cryptocurrency exchanges as the exchanges (where most bitcoins are traded) are more susceptible to security threats. The 2014 Mt.Gox Hack, for instance, is a typical example of how hackers can tamper the transactions and steal bitcoin from the exchanges. In this relatively new literature, the empirical evidence on the efficiency of the bitcoin market is relatively weak, and this is why we want to embark on this endeavour to investigate the effect of hacking events on the price of bitcoin. Furthermore, we attempt to find out if investors can formulate an investment strategy to take advantage of those events. The paper is organised as follows: Section 2 describes the data and methodology used in this study, Section 3 presents the empirical results, and Section 4 concludes the paper.

2 DATA AND METHODOLOGY

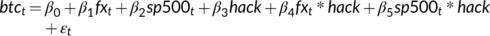

(1)

(1) is the bitcoin returns at time t, calculated as the first log difference of the bitcoin price between time t and t−1,

is the bitcoin returns at time t, calculated as the first log difference of the bitcoin price between time t and t−1,  is the FX returns at time t, calculated as the average returns of the three currency pairs, and

is the FX returns at time t, calculated as the average returns of the three currency pairs, and  is the S&P500 returns at time t, calculated as the first log difference of the S&P500 index.

is the S&P500 returns at time t, calculated as the first log difference of the S&P500 index.| Event | Date | Event |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | 7/02/2014 | Mt Gox Attack |

| 2 | 17/06/2016 | DAO Hack |

| 3 | 2/08/2016 | Bitfinex Hack |

| 4 | 6/12/2017 | NiceHash Hack |

| 5 | 26/01/2018 | Coincheck Hack |

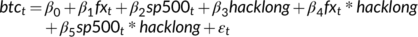

(2)

(2) (3)

(3) (4)

(4) ,

,  and

and  are the lagged variables of FX, S&P500 and BTC return respectively.

are the lagged variables of FX, S&P500 and BTC return respectively. (5)

(5)3 RESULTS

Table 2 displays the descriptive statistic of the variables used in this study. We find, on average, that investing in bitcoin yields significantly higher return than the S&P500 but the bitcoin return is lower than the FX return of the CNY/USD and JPY/USD. Table 3 presents the correlation matrix of the variables, showing a lack of correlation between bitcoin and other assets. This observation is consistent with those made by Yermack (2015) and Baur et al. (2018).

| Bitcoin | USD/CNY | USD/CAD | USD/JPY | S&P500 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean | 0.26 | 0.41 | 0.14 | 0.47 | 0.04 |

| Median | 0.22 | 0.36 | 0.10 | 0.40 | 0.05 |

| Maximum | 34.78 | 1.89 | 1.05 | 2.47 | 3.83 |

| Minimum | −26.96 | 0.01 | 0.00 | 0.01 | −4.18 |

| SD | 4.74 | 0.27 | 0.13 | 0.33 | 0.78 |

| Skewness | −0.11 | 1.33 | 1.97 | 1.76 | −0.56 |

| Kurtosis | 11.02 | 5.67 | 8.89 | 7.84 | 6.39 |

| Observations | 1301 | 1301 | 1301 | 1301 | 1301 |

| Bitcoin | USD/CNY | USD/CAD | USD/JPY | S&P500 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Bitcoin | 1 | −0.033 | −0.023 | 0.005 | −0.003 |

| USD/CNY | 1 | 0.109 | 0.291 | −0.014 | |

| USD/CAD | 1 | 0.12 | −0.050 | ||

| USD/JPY | 1 | 0.011 | |||

| S&P500 | 1 |

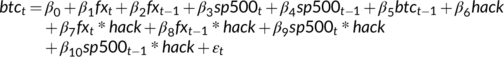

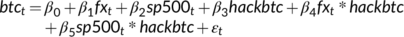

The results of Equation (1) indicate that past bitcoin returns, FX returns and S&P500 returns do not affect bitcoin returns (Table 4). When a hacking event occurs, however, a positive relationship appears between bitcoin returns and FX returns. A plausible explanation for this relationship is that investors might increase their trading activities and make a profit during a hacking event, which requires a substantial amount of foreign currencies pouring into the crypto exchanges, which is, in turn, beneficial for the FX market. On the other hand, we observe a change in market sentiment towards the bitcoin market and the stock market (as proxied by S&P500) when a hack takes place. Our results also show that these effects are limited to BTC-related hacks (see Table 5). For robustness check, we incorporate the lagged variables into the model and the results are consistent with those of Equation (1) as shown in Table 6. The results also show that investors tend to switch their investment to the stock market when the bitcoin price decreases, and vice versa. In addition to the results of Baur et al. (2018), our findings create an opportunity for investors to formulate an investment strategy that takes into account hacking events.

| Variable | Coefficient | SE | t-statistic | Prob. |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Intercept | 0.00 | 0.00 | 1.90 | 0.06 |

| fx | 0.21 | 0.33 | 0.65 | 0.51 |

| sp500 | −0.01 | 0.20 | −0.07 | 0.95 |

| hack | 0.10 | 0.01 | 15.69 | 0.00 |

| fx*hack | 43.86 | 3.84 | 11.43 | 0.00 |

| sp500*hack | −11.75 | 3.38 | −3.47 | 0.00 |

| Variable | Coefficient | SE | t-statistic | Prob. |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Intercept | 0.00 | 0.00 | 1.89 | 0.06 |

| fx | 0.22 | 0.33 | 0.69 | 0.49 |

| sp500 | −0.01 | 0.20 | −0.07 | 0.95 |

| hackbtc | 0.10 | 0.00 | 72.42 | 0.00 |

| fx*hackbtc | 51.10 | 0.33 | 157.03 | 0.00 |

| sp500*hackbtc | −16.55 | 0.20 | −83.84 | 0.00 |

| Variable | Coefficient | SE | t-statistic | Prob. |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Intercept | 0.00 | 0.00 | 1.88 | 0.06 |

| btct−1 | −0.03 | 0.05 | −0.64 | 0.53 |

| fxt−1 | 0.33 | 0.42 | 0.79 | 0.43 |

| sp500t−1 | 0.01 | 0.16 | 0.08 | 0.94 |

| fx | 0.21 | 0.33 | 0.64 | 0.52 |

| sp500 | 0.00 | 0.20 | 0.01 | 0.99 |

| hack | 0.09 | 0.00 | 50.25 | 0.00 |

| fx*hack | 40.96 | 0.80 | 51.32 | 0.00 |

| sp500*hack | −10.97 | 0.77 | −14.30 | 0.00 |

| fxt−1*hack | −14.26 | 1.47 | −9.69 | 0.00 |

| sp500t−1*hack | −4.60 | 0.54 | −8.52 | 0.00 |

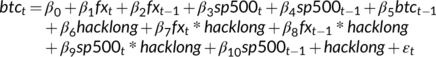

In addition, we examine the long-term effect of these hacking events using Equation (2) that incorporate the hacklong dummy variable to find out if the effect persists in the long term. Our results show that there is no evidence of a persistent effect of a hacking event on bitcoin return and the results are consistent across different models (see Tables 7 and 8).

| Variable | Coefficient | SE | t-statistic | Prob. |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Intercept | 0.00 | 0.00 | 2.16 | 0.03 |

| fx | 0.25 | 0.33 | 0.78 | 0.44 |

| sp500 | −0.11 | 0.16 | −0.69 | 0.49 |

| hacklong | −0.01 | 0.02 | −0.71 | 0.48 |

| fx*hacklong | 1.44 | 2.62 | 0.55 | 0.58 |

| sp500*hacklong | 1.19 | 1.58 | 0.75 | 0.45 |

| Variable | Coefficient | SE | t-statistic | Prob. |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Intercept | 0.00 | 0.00 | 2.13 | 0.03 |

| btct−1 | −0.03 | 0.05 | −0.59 | 0.56 |

| fxt−1 | 0.42 | 0.42 | 1.00 | 0.32 |

| sp500t−1 | −0.03 | 0.18 | −0.15 | 0.88 |

| fx | 0.25 | 0.33 | 0.77 | 0.44 |

| sp500 | −0.09 | 0.16 | −0.62 | 0.53 |

| hacklong | −0.01 | 0.02 | −0.68 | 0.49 |

| fx*hacklong | 1.62 | 2.46 | 0.66 | 0.51 |

| sp500*hacklong | 0.86 | 1.64 | 0.53 | 0.60 |

| fxt−1*hacklong | −3.36 | 4.02 | −0.83 | 0.41 |

| sp500t−1*hacklong | 0.25 | 0.97 | 0.26 | 0.79 |

4 CONCLUSION

The rise of cryptocurrencies, particularly bitcoin, has drawn significant attention from cryptocurrency users, miners and investors as well as the scientific community (Ciaian et al., 2018). Since bitcoin is usually used for investment purposes, it is important to find out if investors can benefit from bitcoin and other financial markets during crypto extreme events.

This paper examines the effects of hacking events on bitcoin returns, producing evidence for a positive relationship between the FX market and the bitcoin market during the hacks. Moreover, the results reveal a negative relationship between the S&P500 and bitcoin returns. Investors can take advantage of the observation that the characteristics of bitcoin are extremely different from those of other financial assets (Dyhrberg, 2016; Katsiampa, 2017). We also find that BTC-related events have significant impact on BTC price while other non-BTC hacks such as DAO or Coincheck have minimal impacts on BTC price. Our results can be used to formulate an investment strategy utilising hacking events and suggest that investors must act quickly to benefit from hacking events since the effects do not last long.

Biographies

Dr Huy Pham is a lecturer in finance at RMIT University in Vietnam, founder of RMIT FinTech-Crypto Hub and a regular member of American Finance Association. His research interests are in the fields of FinTech, cryptocurrencies, environmental finance, asset pricing and empirical finance.

Dr Binh Nguyen Thanh is an active academic thought leader in frontier fields of finance including Financial Technology, Blockchain and Decentralized Finance and has published in leading academic journals on those topics. He also regularly provides expert articles and comments on the digitalization in Economics and Finance in leading regional business outlets, and is a highly demanded speaker who has presented for high-profile institutions in the region.

Dr Vikash Ramiah is an Associate Professor in Finance at University of Wollongong in Dubai. Vikash has been teaching economics and finance courses at the University of South Australia, Royal Melbourne Institute of Technology, University of Melbourne, La Trobe University and Australian Catholic University since 1999. He has published in reputable academic journals and supervises numerous PhD students. His industry experience involves ANZ investment banking, the Australian Stock Exchange, Finance and Treasury Association of Australia, Glomacs and the Australian Centre for Financial Studies. Other services to the community includes being a research fellow for Institute of Global Business and Society, Cologne University of Applied Sciences and Tianjin Academy of Environmental Science. He has established his leadership both domestically and internationally as he is appointed as a Professorial Research Associate at Victoria University, Adjunct Professor at Ton Duc Thang University, Adjunct Associate Professor at UniSA and Professor at Global Humanistic University. He specialises in Applied Finance and his research areas are financial markets, behavioural finance and environmental/sustainable finance.

Dr Nisreen Moosa is a health economist, holding a PhD from the University of South Australia. She also holds a Bachelor of Science degree from the University of Melbourne, a Bachelor of Health Science(RMIT), a Master of Clinical Chiropractic (RMIT) and a Graduate Certificate in Finance (RMIT). She had previously worked as a Chiropractor before she embarked on a change of career in economics and finance. She has published papers in finance and health/environmental economics. She has also co-authored a book entitled “Eliminating the IMF: An Analysis of the Debate to Keep, Reform or Abolish the Fund”, in which she analysed the effect of IMF operations on healthcare expenditure.

Open Research

DATA AVAILABILITY STATEMENT

Data available on request from the authors.

REFERENCES

- 1 We collected the top high-profile hacks from https://blockgeeks.com/guides/cryptocurrency-hacks/.