Globalization and politico-administrative factor-driven energy-growth nexus: A case of South Asian economies

Abstract

In modern days, economic growth is energy-dependent and vice versa. Earlier studies concentrated a bit to analyze the influence of globalization and politico-administrative factors on the energy consumption-economic growth nexus in developing economies. The motivation for the current research is to scrutinize the energy consumption-economic growth nexus while accounting for the influence of globalization and country risk indicators—the politico-administrative factors in a panel of 4 South Asian countries (Bangladesh, India, Pakistan, and Sri Lanka) during 1980–2018. To check the issues of heterogeneity and cross-sectional independence, the study employs the pooled mean group estimation method. The investigated results provide a nexus between energy consumption and economic growth where globalization - a long-run force positively affects this nexus in the long run and negatively in the short run. Besides, the politico-administrative factors have an adverse impact in the long run and an insignificant effect on this nexus in the short run. The Dumitrescu–Hurlin non-causality test establishes the feedback hypothesis concerning energy consumption-economic growth nexus in South Asian economies. The study results remain robust across the dynamic ordinary least square estimator. Therefore, this study suggests sustaining the energy-growth nexus to properly handle globalization and politico-administrative and the Covid-19 pandemic issues through institutional quality. Moreover, the objective-oriented policies are critical to strengthening the energy-growth nexus without decaying environmental quality in South Asian countries.

1 INTRODUCTION

Energy is considered a key instrument for the production and operation of all types of goods and services in economies. Therefore, the spectacular growth of the world economies is largely dependent on energy consumption. More importantly, energy infrastructures (EIs) stimulate the economic growth process and improve the life standard of people (Singh & Vashishtha, 2020b). Also, energy efficiency has become instrumental in developing the quality of people's life and wellbeing. National Energy Policy drafted by NITI Aayog highlights energy efficiency as a unique force in obtaining its four important targets, including access to affordable energy, increased security for energy, and its independence, sustainability, and growth in the economy (Singh & Vashishtha, 2020a). On the other hand, if an economy is developed using energy input, governments of different countries should adopt energy-efficient policies. These policies include an effective and strategic way of favoring multifarious goals to promote impressive energy access; offer more energy services for households and businesses; encourage energy-efficient equipment, productions, and services for market growth; decrease adverse climatic and environmental effects and improve the security of energy. Thus, energy consumption and economic growth are positively related to each other in an economy.

On the other hand, energy consumption and income growth are not always related to each other (Joyeux & Ripple, 2007; Jumbe, 2004; Lee, 2005) and in some cases, the adverse association between them exists in the perspective of different developing and under-developing economies (Carfora et al., 2019; Squalli, 2007). This happens as these countries lack proper energy management policies and energy infrastructural facilities that keep both the people and industries away from consuming and utilizing energy resources for production as well as economic growth. The capacities of the states are mainly responsible for impeding energy-induced economic growth and growth-driven energy consumption in these countries.

The interrelated linkage between energy consumption and economic growth is largely stimulated by globalization for different economies. Globalization entails homogenization (Waltz, 1999) and integration in economic, political, and social affairs among different countries (M. M. Islam, 2019). Keohane and Nye (2000) and M. M. Islam (2019) illustrated “globalization as economic globalization—described as long-distance movements of capitals, goods, and services as well as information and ideas, which accompany the exchanges of the market; political globalization—expounded by a dispersion of governmental policies; and social globalization—disclosed as the flows of information, ideas, images, and people.” This integrated principle of globalization makes people's life convenient to boost up consumption, advance technology diffusion, and ensure various socioeconomic and political adaptations and developments (M. M. Islam & Islam, 2021). More importantly, the energy consumption level of people significantly relies on the globalization process as globalization/economic globalization and trade liberalization by removing trade barriers facilitate outputs and income flows among countries. A country strives to participate in diverse global agencies, associate with worldwide NGOs, sign international agreements to promote political globalization (UNCTAD, 2017). Besides, the subscription and purchase of telephones and cellular phones, and the arrangement of tourists' easy visa process are related to social globalization (World Bank, 2020b). Thus, economic, political, and social dimensions of globalization develop EIs, enhance people's energy-related activities, energy consumption, and hence, economic growth (M. M. Islam et al., 2021). Globalization is aggregately considered a key stimulus to the consumption of more energy, which is investigated in much empirical literature (Shahbaz et al., 2018a). Some empirical shreds of evidence such as Akarca and Long (1980); Wolde-Rufael (2005); Chang and Berdiev (2011) and Marques and Fuinhas (2016) support that a greater level of energy use induced by the flow of globalization leads to the prosperity of world community by enabling them to lead a standard life and stimulate economic development.

Globalization is a long-run external force that harnesses both energy consumption and economic growth. This process of globalization-driven energy-growth nexus does not work properly if there is a lack of stable human rights situations in countries. If human rights are violated due to the existence of political instability, the energy consumption-economic growth nexus is constrained (M. M. Islam & Islam, 2021). This sort of country risk indicator (CRI) leads to negative externality that is, making the globalization process dysfunctional. The CRI include socio-economic crisis, internal conflict, external conflict, corruption, military in politics, religious tensions, vulnerable law and order situation, ethnic tensions, undemocratic rules, and inefficient bureaucracy, etc. (PRS Group, 2019). The lack of due role of these politico-administrative elements of the country somewhat motivates political terrorization, resulting in political instability. The relationship between political instability and economic growth can be explained by analyzing Grossman's (1991) theory of revolutions. He claims that if a country's government is comparatively weak, the chance of revolution is high. It implies that the weak ability of a government hardly meets up the demands of the general masses. Therefore, this situation instigates people to follow the revolutionary way rather than the productive way of market growth.

Besides, volatile state-affairs such as processions, hartals (shutdown), strikes and violence, crimes, coups and counter-coups, the reversal of regimes, and the overthrow of governments through agitations are usually associated with political instability. This unstable circumstance pushes a state for reaching the state of a “failed state” (Alesina et al., 1996). In addition, investment and business environments are highly hindered by political uncertainty as entrepreneurs, clients, buyers, and stakeholders are usually failed to move properly for business and take proper decisions. As a result, this vulnerable condition poses a serious threat to the performance of macroeconomic indicators and economic growth (Murad & Alshyab, 2019). Political instability promotes political terrorization in which various terrorist groups intend to demolish the energy transmission infrastructures (ETIs) by hindering proper energy supplies, consumption, and hence, economic growth (Toft et al., 2010). Overall, it can be concluded that the politico-administrative dynamic such as CRI may influence the energy consumption-economic growth nexus in economies especially developing economies.

Deviated from man-made disasters, natural calamities, chronic diseases, viruses like the Covid-19 pandemic have become significant elements to affect global economic growth. Due to the effect of a novel coronavirus, mostly the developing countries have been facing serious disasters in the different fields of economy and society (Kumar & Pinky, 2020; Q. Wang & Su, 2020). Job loss, inequality, poverty, and the overall low living standard of the people have been the ultimate consequence of different economies (Hossain, 2021). Through demolishing public health, the Covid-19 pandemic has adversely reduced economic activities and hence economic growth (Alhassan et al., 2020). The energy consumption level of the people has highly been hindered due to the pandemic. On the other hand, the risk of the Covid-19 pandemic has forced world people to bring a substantial change in their lifestyle concerning energy consumption. During the lockdown, people stay in the house that has increased household-level consumption of energy (Rouleau & Gosselin, 2021). But the industrial use of energy has decreased because of the shutdown of energy-intensive mills and factories in different countries (Q. Wang & Su, 2020). Moreover, in recent years, the risk of Covid-19 has been added to affect the sphere of energy-growth nexus along with the menace of politico-administrative factors in the world's most countries.

South Asian countries have been witnessing a substantial surge in urbanization, industrialization, and population growth that have significantly raised the energy demand. The escalating import dependency of these countries has led to ample gross energy demands, rising to 24.76% in 2010 from 10.43% in 1971. This scenario of higher energy consumption has highly appeared in the context of India, Bangladesh, Sri Lanka, and Pakistan, though the consumption of energy and electricity per capita of this region is still less than one-third of the global average (Vidyarthi, 2015). South Asia is the abode of one-fourth of the world's population and is called one of the most consumers of energy worldwide. The report of the US-based Energy Information Administration reveals that the primary energy consumption of this region rose by 58 percent from 1991 to 2000, and is predicted to enhance by more than 40 percent by 2040. Besides, energy intensity that is, total energy consumption per unit of GDP is 0.65 toe in comparison with the global average of 0.29 toe (Gupta, 2015).

South Asian countries intend to overcome the deficiency of energy resources for stimulating economic growth. Therefore, energy has been adopted as the requisite component for spurring the production process. Operating weighty pieces of machinery and electrical tools, transporting raw materials and finished goods from one place to another necessitate immense energy consumption to continue industrial productions. So, energy use for firms' production functions is currently regarded as the key input in stimulating GDP growth in South Asian economies. Besides, the growing GDP of this region is achieved through the existing labor force and capital stocks along with the increase in energy consumption. More importantly, the governments of this region intend to secure the continual accessibility of energy at affordable prices for enhancing the local commodities' prices in international markets. This leads to boosting the net volume of exports and further economic growth via the multiplier effect. On the other hand, increasing growth momentum has enhanced people's income and consumption especially energy consumption capacity. Besides, the income increment of the people stimulates the investments in industries requiring energy (Shakeel et al., 2014). Thus, people's capacity for consumption and investment has been instrumental in spurring economic growth in South Asian economies.

South Asia as a region is still unaffected by the protectionism imposed by the developed economies though there is an existence of striking backlash against globalization (World Bank, 2017). The vibrant process of globalization is measured through the flows of remittances, trade, and foreign direct investment (FDI), which are at a substantial growing stage in this region. In the recent decade, remittance inflows in these economies are stable and reserves of foreign currencies are mostly at a comfy level though there appears a drastic fall of remittance flows generated by the lower prices of oils in 2014. Moreover, strong local demands, accrual in exports, and augmented inflows of FDI have pointed to this favorable position. South Asian trade diversion process is on track to be benefitted from the global economy. This region also sets itself to achieve from the experimented growth recuperation in developed economies, as these counties are the major markets for exports. However, the existing globalization backlash is not dissuading the South Asian nations due to having a powerful external orientation (World Bank, 2017).

A stable politico-administrative situation is a precondition for the success of energy consumption-economic growth tie in any economy. In many South Asian countries, political instability and full-scale uprising constrain policymakers to adopt pro-consumption as well as pro-growth policies. Sometimes, investments in manufacturing sectors are observed to be complex as it involves long gestation periods, dependable equipment, and established policy regimes. It is very hard to properly utilize all these growth-related logistics and supports during volatility and insurgency. Besides, the institutional quality of relevant sectors is also hampered due to the malfunctions of different development-oriented dynamics such as bureaucracy, political parties, law and order, ethnic harmony, democratic accountability, etc. (Nabi et al., 2010), which is usually prevailed in most of the South Asian countries.

Apart from politico-administrative risk factors, the global economy has been witnessing a colossal shock to economic growth due to the Covid-19 pandemic (Usman et al., 2020) as consumption and production are scaled back (Debata et al., 2020). Similarly, South Asian economies have tremendously been affected by the risk of the Covid-19 pandemic because of their huge population, poor infrastructure, and lower monitoring mechanism (Sharma et al., 2020). Themajor South Asian country i.e. India has been facing a serious unemploymentproblem, fiscal deficits that have resulted in slow progress in this economy (Rakshit & Basistha, 2020). Besides, the Covid-19 pandemic has sharply hit the South Asian countries that have disrupted the overall energy efficiency level (Iqbal et al., 2021). Moreover, the risk of the Covid-19 has affected the energy-growth relationship of these countries.

This vulnerable politico-administrative and the Covid-19 situations of South Asian countries motivate us to conduct this study to check how these risk issues affect the relationship between energy consumption and economic growth. The politico-administrative factors cannot be ignored while scrutinizing the influence of any economic indicator on another in the context of South Asian countries. Besides, although South Asia is free from the apparent protectionism of globalization imposed by the developed economies, there exists a striking repercussion among the people of this region against globalization or global force (World Bank, 2017). This also motivates to include the indicator of globalization in examining the relationship between energy consumption and economic growth. Moreover, a higher level of energy use for household and commercial purposes stimulates income growth in this region. Economic growth requires the proliferation of industrialization and urbanization, which also needs energy use. This is the core motivation of this study to inspect how energy consumption and economic growth are related to each other in the context of South Asian countries. Therefore, this study examines the energy consumption-economic growth linkage in the presence of globalization and politico-administrative factor (henceforth CRI) in a panel of 4 South Asian countries viz. Bangladesh, India, Pakistan, and Sri Lanka covering the time from 1980 to 2018.

This research contributes to the current literature mainly by four folds: (i) this study delves into the influence of the CRIs such as politico-administrative factors and the external force (globalization) on the relationship between energy consumption and economic growth in South Asia; (ii) the inclusion of the KOF-produced composite index of globalization—covering political, economic, and social dimensions of globalization, and the CRI developed by the international country risk guide (ICRG), which is not utilized by the earlier researchers in a single study model; (iii) the composite globalization index (Gygli et al., 2018) and the aggregate values of ICRG (PRS Group, 2019) are measured by weights using principal component analysis (PCA), which is the significant value addition to the existing literature; and (iv) investigating a two-way relationship between energy consumption and economic growth (dependent variables) by including two predictor variables namely globalization and politico-administrative dynamics in two separate models (Model 1 and Model 2) that can be characterized as a novel approach.

The methodological contribution of this paper is also distinctive comparing to other previous studies. This paper utilizes the cross-sectional dependence (CD) test (Pesaran, 2004), second-generation unit root tests that is, CADF (Pesaran, 2007), and CIPS (Pesaran et al., 2013), and the panel cointegration test (Westerlund, 2007) as the pre-estimation techniques. Besides, pooled mean group (PMG) estimator is employed to measure the long-run and short-run relationship among the variables. This method significantly checks the issue of heterogeneity and cross-sectional independence that existed in a sample of panel data (Baloch et al., 2020). The Dumitrescu & Hurlin (D-H) (2012) panel Granger causality test is used for analyzing the causal association among the variables. The dynamic ordinary least square (DOLS) method coined by Stock and Watson (1988) is employed to check for the robustness of the study findings obtained from the PMG technique.

2 LITERATURE REVIEW

There exists a gap in the empirical literature in delving into the effect of globalization and politico-administrative factors on the connection between energy consumption and economic growth in South Asian countries. From the theoretical perspective, existing pieces of empirical studies (Akarca & Long, 1980; M. M. Islam & Islam, 2021; Marques & Fuinhas, 2016; Wolde-Rufael, 2005) divide the energy consumption-economic growth nexus into four dimensions. First is the “neutrality hypothesis” that expresses no causality between energy use and growth; second is the “conservation hypothesis,” depicting unilateral causation from growth to energy use; third is the “growth hypothesis,” revealing the unilateral causal relationship from energy use to growth; and last is the “feedback hypothesis,” establishing the bilateral causation between energy use and growth. These all types of the causal connection between energy use and growth are greatly associated with globalization (Chang & Berdiev, 2011; Marques et al., 2017; Shahbaz et al., 2016) and politico-administrative country risk issues (M. M. Islam & Islam, 2021; Rodriguez et al., 2020; Toft et al., 2010).

With the augmented flow of globalization via trade openness, exports and imports, several authors are motivated to study on energy consumption-economic growth nexus utilizing these indicators. Based on Antweiler et al. (2001) theoretical method, Cole (2006) explored that globalization proxied by the trade openness significantly spurs the energy consumption level of the people in 32 developing and developed countries. In the case of 7 South American economies, there exists bidirectional causation between exports and energy use, and imports and energy use as revealed from the investigation of Sadorsky (2012). The very recent study of S. Ali and Malik (2021) revisited the nexus between globalization and economic growth for the panel of 124 countries during 1996–2017 and found that a marginal change in economic globalization will not affect the income growth in these economies.

The studies of F. Islam et al. (2013) and Shahbaz and Lean (2012) incorporated some variables such as industrialization, population, urbanization, financial openness and confirmed the nexus between energy consumption and income growth in the context of developing economies applying the bi-variate model. Utilizing trade openness and CO2 emissions, Apergis and Ozturk (2015) and Farhani and Ozturk (2015) established the relationship between energy use and economic growth. These studies emerged in the economic literature with their exclusive use of these variables. Kyophilavong et al. (2015) and Shahbaz et al. (2016) in the context of individual countries, and Nasreen and Anwar (2014) and Sadorsky (2012) in the context of panel countries found a unilateral causal association from income growth to trade openness. More specifically, Adedoyin et al. (2021a) concluded that the economic growth and non-renewable energy consumption induce emissions and economic policy uncertainty has a moderation effect upon the role of renewable and non-renewable energy generation that contributes to reducing emissions in Sub-Saharan Africa during 1996–2014.

The use of globalization indicators divided into political, economic, and social dimensions appears in many studies. Globalization helps decrease the demand for energy in India (Shahbaz et al., 2016). In the case of 43 countries, the relationship between economic growth and energy use is positively impacted by the social, political, and economic dimensions of globalization (Marques et al., 2017). There is a significant long-term positive impact of energy consumption on income growth whereas bilateral causal relations are detected among energy consumption, globalization, and income growth in Nigeria (Iheanacho, 2018). The positive correlation between globalization and energy use is found in the perspective of the Netherlands and Ireland (Shahbaz et al., 2018b). On the other hand, Tugcu et al. (2012) analyzed the relationship between energy use and income growth in the context of G-7 economies and established that energy consumption alone does not spur economic growth; rather production function has a significant role while investigating the nexus between energy and growth. M. S. Islam and Ali (2011) investigated the linkage between energy consumption, economic growth along with gross capital formation, and export earnings in Bangladesh using data for the period 1971–2010. The study applied the VECM framework and exhibited that energy consumption positively influenced economic growth both in the long and short run. The study of Etokakpan et al. (2020) has a key contribution to make proof of the role of globalization and income growth in the energy efficiency of Turkey. Baloch et al. (2021) explored a long-run association of globalization with energy innovation in the context of OECD economies during 1990–2017 utilizing PMG/ARDL approach.

More exceptionally, the energy use and economic growth level of China especially the spillover effect of these factors on North and South America, Asia Pacific and Africa, Central Asia and Europe, and Middle Eastern countries were investigated by Marques et al. (2019) during 1970–2016. The Granger causality analysis established the feedback hypothesis for whole regions. Specifically, feedback proposition prevails in Asia Pacific and America; and conservation hypothesis exists in the Middle East and Africa, Central Asia, and Europe. The empirical investigation of Topcu et al. (2020) found a significant positive impact of energy use on income growth for the high and middle-income economies; and a unilateral causal association, running from energy use to income growth for all income-classified economies. H. S. Ali et al. (2020) found an electricity consumption-induced income growth in the context of Nigeria within a trivariate model approach. A similar finding was discovered by Nathaniel and Bekun (2021) in the case of Nigeria covering the period of 1971–2014. Intending to investigate the economic performance-driven CO2 emissions, Udemba et al. (2021) discovered a significant contribution of energy consumption upon the stimulation of economic growth as per the findings obtained from both the ARDL and causality analyses in the case of India. The positive influencing profile of energy consumption on income growth was also confirmed by the study of Azam and Abdullah (2021) while investigating the relationship between energy consumption, tourism, and economic growth in the context of top tourist destinations in Asia. On the other hand, Sharma et al. (2021) discovered a negative influencing profile of energy consumption on economic growth in the case of 10 emerging and developing countries in Asia during 2000–2017.

In recent times, there is a tendency of empirical investigations to incorporate politico-administrative factors, country risk as well as institutional quality indicators while investigating the energy use—income growth nexus mainly in the context of developing economies. Toft et al. (2010) argued that EIs are affected by the political terrorization that constrains the protection of the energy supply. A viable energy supply strengthens the operational mechanism of society and its advancement. Potential invaders attempt destructing the ETIs such as gas and oil pipelines, tankers at sea, pylons, and electricity substations. Several empirical pieces of literature (Baev, 2006; Giroux, 2008; Kjøk & Lia, 2001; Tørhaug, 2006; Verma, 2007; Weinberg et al., 2008) examined the vulnerabilities of ETIs caused by the political terrorization.

The study done by Bercu et al. (2019) found the causal association between electricity consumption and income growth, which is positively induced by good governance in 14 Central and Eastern European countries throughout 1995–2017. The relationship between energy consumption, environmental quality, political instability, corruption, and economic development is scrutinized by Sekrafi and Sghaier (2018) in 13 MENA countries during 1984–2012. The energy consumption-economic growth nexus is affected by corruption both directly and indirectly whereas political instability harms this nexus. Azam et al. (2020) developed an institutional quality index, including democratic accountability, political stability, and administrative ability, which has a positive effect on energy consumption in the context of 66 developing economies from 1991 to 2017. Most recently, M. M. Islam and Islam (2021) discovered a nexus between energy consumption and economic growth during 1971–2018. The study output specifically revealed that political risk issue measured by the political terror scale heterogeneously affects this nexus in the context of Bangladesh. The study of Adedoyin et al. (2021b) explored the positive role of governance performance in escalating trade—the key determinant of economic growth in the context of 23 European economies throughout 1998–2017.

The above-mentioned works of literature utilized different variables such as exports, imports, trade openness, globalization as external determinants and population, financial openness, industrialization, urbanization, political instability, corruption as endogenous variables while examining the energy consumption—economic growth nexus in different countries' perspectives. More importantly, previous pieces of literature seldom integrate the KOF's composite globalization index and ICRG's CRI index as the politico-administrative factor in examining this nexus in the global and South Asian perspectives. The existing study is thus deviated from using these two indices (globalization and CRI) in exploring the relationship between energy consumption and economic growth in the context of South Asian countries. Therefore, this empirical investigation would fulfill the study gap by analyzing the nexus between energy consumption and economic growth within the purview of globalization and politico-administrative factor viz. CRI utilizing currently used second-generation panel econometric techniques in the context of South Asia.

3 METHODOLOGY

The methodology part of this study is evolved around the model specification, data elaboration, and econometric methods used.

3.1 Model specification

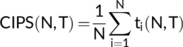

(1)

(1) (2)

(2)In Equations (1) and (2), i shows the ith country used in the panel; t stands for the time from 1980 to 2018;  means the constant;

means the constant;  denotes the coefficients of energy consumption (lnEC) and economic growth (lnGDP) in Equations (1) and (2), respectively;

denotes the coefficients of energy consumption (lnEC) and economic growth (lnGDP) in Equations (1) and (2), respectively;  and

and  represent the coefficients of globalization (lnGLO) and CRI, respectively, and

represent the coefficients of globalization (lnGLO) and CRI, respectively, and  denotes the error term.

denotes the error term.

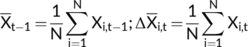

3.2 Data specifications

This study utilizes a panel dataset encompassing the economic growth (GDP), energy consumption (EC), globalization (GLO), and CRI for the period of 1980–2018 in four South Asian countries (Bangladesh, India, Pakistan and Sri Lanka). The study considers the data on economic growth (GDP) per capita; energy consumption (EC) per capita; and KOF Globalization Index (GLO) that includes economic, political, and social dimensions of globalization with their 42 different variables and is calculated by using statistically measured weights that is, PCA. This study also adopts the ICRG index as the CRI that consists of 12 politico-administrative components, and the scale of risk points allotted to each, are “government stability (0-12), socio-economic conditions (0-12), investment profile (0-12), internal conflict (0-12), external conflict (0-12), corruption (0-6), military in politics (0-6), religious tensions (0-6), law and order (0-6), ethnic tensions (0-6), democratic accountability (0-6) and Bureaucratic Quality (0-4)” (PRS Group, 2019). All these components of CRI are converted into a single unit/variable by computing through PCA.

The data of economic growth and energy consumption are extracted from the World Bank Development Indicators (WDI) published by World Bank (2020); globalization data are sourced from the KOF globalization index developed by KOF Swiss Economic Institute (Gygli et al., 2018); and the CRI data are collected from the ICRG published by PRS Group (2019). Finally, this study considers natural logarithm values of economic growth, energy consumption, and globalization index except for CRI in estimation to reduce heteroscedasticity in the data. As the PCA computed CRI data contain negative values, performing a natural log is not suitable from the theoretical intuition of statistical analysis.

First, this paper estimates the descriptive statistics (Table 1) to check for whether the data are homogenous and normally distributed.

| Source | Variable | Description | Obs. | Mean | SD | Min | Max |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| World Bank (2020) | lnGDP | Gross Domestic Product (GDP)—corresponds to per capita GDP (Constant 2010, US$). | 156 | 6.817 | 0.572 | 5.884 | 8.280 |

| World Bank (2020) | lnEC | Energy Consumption (EC)—corresponds to per capita primary energy consumption. | 156 | 5.776 | 0.493 | 4.652 | 6.555 |

| KOF Swiss Economic Institute (Gygli et al., 2018) | lnGLO | The composite globalization index includes the economic, social, and political dimensions with 42 different variables measured by weights using PCA. | 156 | 3.770 | 0.256 | 3.159 | 4.134 |

| PRS Group (2019) | CRI | The country risk indicators (CRI) index encompasses 12 politico-administrative indicators that are made into a single variable using PCA. | 156 | 0.553 | 1.802 | −3.838 | 3.637 |

- Note: ln denotes the natural logarithm.

From the display of descriptive statistics of all variables in Table 1, we see small SD among the series, confirming the normal distribution of the data.

3.3 Econometric methods

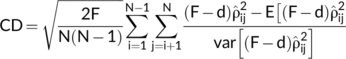

3.3.1 CD test

(3)

(3) denotes the correlation between each pair of the residuals obtained from ordinary least squares (OLS) estimation. The CD test is also suitable for panel data of small cross-sectional dimensions with small-time dimensions (Le & Sarkodie, 2020).

denotes the correlation between each pair of the residuals obtained from ordinary least squares (OLS) estimation. The CD test is also suitable for panel data of small cross-sectional dimensions with small-time dimensions (Le & Sarkodie, 2020).3.3.2 Panel unit root test

(4)

(4) (5)

(5) (6)

(6) .

.3.3.3 Panel cointegration test

(7)

(7) indicates the coefficient of the error correction term for each unit of CD.

indicates the coefficient of the error correction term for each unit of CD. and

and  statistics) determine whether there exists any cointegration in at least one cross-sectional unit.

statistics) determine whether there exists any cointegration in at least one cross-sectional unit.

(8)

(8) (9)

(9) and

and  statistics are employed as following equations:

statistics are employed as following equations:

(10)

(10) (11)

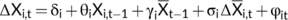

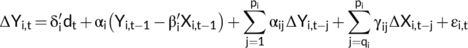

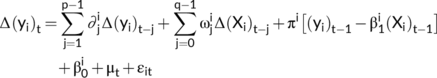

(11)3.3.4 PMG estimation

(12)

(12) and

and  represent short-run coefficients;

represent short-run coefficients;  denotes the error correction adjustment speed;

denotes the error correction adjustment speed;  indicates the long-run coefficients;

indicates the long-run coefficients;  ,

,  and

and  are the country-specific fixed effects, time-variant effects, and stochastic error term, respectively.

are the country-specific fixed effects, time-variant effects, and stochastic error term, respectively.3.3.5 Panel causality test

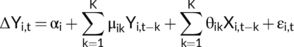

(13)

(13) and

and  denote the coefficients of

denote the coefficients of  and

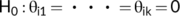

and  for cross-sectional dimension (i = 1, 2, …, N), respectively; t represents the time period dimension (t = 1, 2, …, T) of the panel. The estimated coefficients are expected to differ across units and be fixed over the long-term. The lag K is assumed to be similar for all cross-sections. The null hypothesis can be described as:

for cross-sectional dimension (i = 1, 2, …, N), respectively; t represents the time period dimension (t = 1, 2, …, T) of the panel. The estimated coefficients are expected to differ across units and be fixed over the long-term. The lag K is assumed to be similar for all cross-sections. The null hypothesis can be described as:

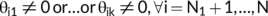

(14)

(14) (15)

(15) (16)

(16) .

. = ・ ・ ・ =

= ・ ・ ・ =  = 0. The next step is to take the average of the test statistics (Wald statistics), as presented in Equation (17):

= 0. The next step is to take the average of the test statistics (Wald statistics), as presented in Equation (17):

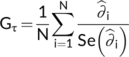

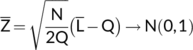

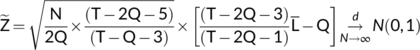

(17)

(17) represents the individual cross-section Wald statistics in time T and

represents the individual cross-section Wald statistics in time T and  is the mean value of

is the mean value of  .

. are independent and identical over cross-sections, the linear combination of

are independent and identical over cross-sections, the linear combination of  and Q (i.e.,

and Q (i.e.,  ) will follow a standard normal distribution as presented below:

) will follow a standard normal distribution as presented below:

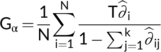

(18)

(18) , which is adjusted for fixed T dimension, will also have standard normal distribution:

, which is adjusted for fixed T dimension, will also have standard normal distribution: (19)

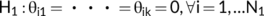

(19)3.3.6 Panel DOLS technique for robustness check

Finally, this study applies the panel DOLS technique developed by Stock and Watson (1988) for testing the robustness of the study findings. This technique utilizes the lead and lag (right-hand side) variables in differentiated forms to control for endogeneity and autocorrelation issues. This procedure is prominent over other alternative estimators due to its application in the case of small samples. Besides, its application not only accommodates higher integration order but also represents the likely simultaneity within the regressors (Masih & Masih, 1996).

4 EMPIRICAL FINDINGS AND DISCUSSIONS

At the outset, we investigate CD in panel data. The Pesaran (2004) CD test is employed, and the results for the CD test presented in Table 2 that support the existence of CD in the panel at the 1% significance level (p < 0.01).

| Variables | Statistics | p-value | Corr | Abs (corr) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| lnGDP | 14.96 | 0.000*** | 0.978 | 0.978 |

| lnEC | 13.52 | 0.000*** | 0.884 | 0.884 |

| lnGLO | 14.89 | 0.000*** | 0.973 | 0.973 |

| CRI | 13.30 | 0.000*** | 0.870 | 0.870 |

- Note: The symbol *** denotes the 1% level of significance.

Next, we conduct the panel unit-root test. The CADF and CIPS panel unit root tests results are presented in Table 3. The results reveal that variables are in a mixed order of integration I(0) and I(1). Variables lnGLO and CRI are found to be stationary at level, while lnGDP and lnEC are reported stationary at first differences.

| CADF unit root test | CIPS unit root test | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Variables | Levels | First differences | Levels | First differences |

| lnGDP | −2.364 | −3.847*** | −1.701 | −4.319*** |

| lnEC | −2.072 | −3.880*** | −1.390 | −5.185*** |

| lnGLO | −2.622 | −4.753*** | −2.404** | −5.301*** |

| CRI | −2.741 | −4.572*** | −2.758** | −5.650*** |

- Note: ***, and ** * denote 1%, and 5% levels of significance, respectively.

Then, this study applies the Westerlund (2007) cointegration test, and the results are reported in Table 4. Since all four test statistics are significant at the 1% level, there is cointegration among the variables. In other words, there is a long-run relationship among economic growth, energy consumption, globalization, and CRI.

| Statistic | Value | Z-value | p-value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Gτ | −4.435 | 5.950 | 0.000*** |

| Gα | −16.177 | 2.995 | 0.001*** |

| Pτ | −7.918 | 3.794 | 0.000*** |

| Pα | −13.820 | 3.381 | 0.000*** |

- Note: The symbol *** represents the 1% level of significance.

At this stage, this study utilizes the PMG estimation technique based on Equations (1), (2), and (12) to find out the long-run and short-run relationships. The results are depicted in Table 5.

| Dependent variable: lnGDP | PMG estimation | Dependent variable: lnEC | PMG estimation | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Coefficient | SE | Coefficient | SE | ||

| Long-run coefficients | Long-run coefficients | ||||

| lnEC | 0.6445** | 0.2631 | lnGDP | 0.5902*** | 0.1056 |

| lnGLO | 2.0932*** | 0.3639 | lnGLO | 0.6486*** | 0.0812 |

| CRI | −0.0866*** | 0.0181 | CRI | −0.0032 | 0.0065 |

| Error correction coefficient | −0.0861** | 0.0459 | Error correction coefficient | −0.6149** | 0.2458 |

| ΔlnEC | 0.2912*** | 0.1019 | ΔlnGDP | 0.1470 | 0.1852 |

| ΔlnGLO | −0.2105*** | 0.0401 | ΔlnGLO | −0.0667 | 0.1300 |

| ΔCRI | 0.0120 | 0.0091 | ΔCRI | −0.0010 | 0.0084 |

- Note: Symbols ***, and ** denote significance at 1%, and 5%, respectively.

The investigated results depict that both economic growth and energy consumption positively and significantly impact each other in the long run in South Asian economies (Table 5). Hence, this result establishes the nexus between energy consumption and economic growth in South Asia. Governments of different South Asian countries consider energy as the key component for spurring the production process. The motive of these governments is to secure faster economic growth in line with the growth-centric policies adopted by the governments of advanced economies worldwide. South Asian economies utilize energy sources to operate heavy machinery and electrical tools, transport raw materials, and finish goods for rapid industrial production. Firms' production capacity and output have tremendously been dependent on energy resources. Local firms' outputs have been accelerating the way of industrialization and hence, GDP growth in South Asian economies.

One of the positive phenomena of South Asian countries is that of their abundance of the cheap labor force that helps reserve the capital. Thus, the more economic output of this region is achieved through the existing labor force and capital stocks along with an increase in energy consumption. Besides, these economies are very adamant in securing consumers' proper access to energy at affordable prices to increase local commodities' prices in global markets. This contributes to boosting the net volume of exports and economic growth via the multiplier effect (Shakeel et al., 2014). The positive effect of energy consumption on economic growth in South Asian economies obtained from this study finding is consistent with M. S. Islam and Ali (2011); Alam et al. (2012); Ouedraogo (2013); Mahalik and Mallick (2014); Marques and Fuinhas (2016); Esen and Bayrak (2017); Iheanacho (2018); Shahbaz et al. (2018a); Sarker et al. (2019); Topcu et al. (2020); H. S. Ali et al. (2020); M. M. Islam and Islam (2021) and Udemba et al. (2021), who mainly established these findings based on the causal analysis in the context of different countries. This study finding is contradictory with Joyeux and Ripple (2007); Jumbe (2004); Lee (2005); Squalli (2007); Carfora et al. (2019) and Sharma et al. (2021). These researchers argued that the lack of energy management policies and the capacity of various states constrains energy-induced economic growth in different countries. The study of Carfora et al. (2019) is also inconsistent with the current study finding while utilizing a categorical variable used namely renewable energy generation to explore the relationship between energy consumption and economic growth in four Asian countries over the period 1971–2015. The ECM-based t-ratio coefficients outcome divulges a negative influence of energy consumption on economic growth in Indonesia and Thailand.

On the other hand, the increasing momentum of economic growth has enhanced the people's income and consumption especially energy consumption capacity in the economies of South Asia (Table 5). Income increment of the people stimulates the investments in industries that require energy. Thus, people's capacity for consumption and investment has been instrumental to spurring the economic growth in South Asian economies (Shakeel et al., 2014). Recently, the regional growth of South Asia is now predicted to be 7.7 percent in 2020 as it has been maintaining an annual 6 percent growth rate in the last 5 years (World Bank, 2020a). The positive long-run influence of economic growth on energy consumption found from this study result is coherent with Marques and Fuinhas (2016); Alam et al. (2017); Shahbaz et al. (2018b); Sarker et al. (2019) and M. M. Islam and Islam (2021). These researchers conclude that higher income growth contributes to a higher level of energy consumption in the context of developing economies. But the study of Esen and Bayrak (2017) is incoherent with the existing study's finding, implying that the higher level of economic growth in income-classified countries is associated with the decrease in energy consumption. Therefore, the study suggested an efficient utilization of energy resources in these economies. Besides, the finding of Vidyarthi (2015) is in the same line in the context of South Asian countries while exploring a unidirectional causality from energy consumption to economic growth.

The investigated findings also explore that globalization positively impacts both energy consumption and economic growth in the long run in South Asian economies (Table 5). Through the globalization process, foreign firms access the different economies of the world. These firms boost up the level of energy consumption as their goal is not to preserve energy, but to maximize profit from the host economy using and investing in energy resources. In this context, the role of globalization on energy consumption is usually discussed in three ways, such as “the scale effect, the technique effect, and the composition effect” (Shahbaz et al., 2018a). Globalization via scale effect channels augment economic activities and hence, energy consumption if ceteris paribus (Cole, 2006). The technique effect is much concerned with globalization that facilitates the economies to decrease the consumption of energy through importing sophisticated technologies and finally, it allows performing more economic activities (Antweiler et al., 2001; Dollar & Kraay, 2004). Lastly, the globalization-induced composition effect on energy consumption takes place when energy use reduces with the growing economic activities (Stern, 2007). Besides, globalization permits a country to move its production functions from farming sectors to manufacturing industries and, ultimately to service sectors. In this way, the production system can be renovated where the energy demand reduces and environmental safety is assured (Jena & Grote, 2008).

South Asian economies are predominantly associated with the scale effect of globalization to stimulate economic growth by increasing energy consumption as much as they can. Some of the counties in this region follow the path of technique effect of globalization to reduce energy consumption by boosting the imports of modern technologies for economic growth. The composition effect of globalization is hardly practiced by these countries of South Asia to reduce energy consumption and improve environmental quality. These countries mainly intend to accelerate trade liberalization (globalization) by easing the trade barrier to achieve economic output and income. To this end, they have taken energy consumption as a significant pushing factor for economic growth. The promotion of globalization is thus related to more energy consumption (Shahbaz et al., 2018a). The favorable effect of globalization on energy consumption in South Asian economies adopted from this study finding is supported by the studies of Shahbaz et al. (2016); Dogan and Deger (2016); Murshed et al. (2018); Tang et al. (2020) and Etokakpan et al. (2020). These researchers highlighted the positive role of globalization in the increase in energy consumption and sustainable management of energy resources in different developing countries. A slight deviation is explored in the study of Shahbaz, Shahzad, et al. (2018) in the way that the negative and positive shocks to globalization lead to similar changes in energy consumption in BRICS countries. Besides, globalization does not cause energy consumption in its volatile profile in top Asian countries as discovered by Hussain et al. (2020).

The positive impact of globalization on economic growth in South Asia is also relevant (Table 5) with the ambit of both theoretical and practical aspects. Globalization generally encompasses the economic, political, and social dimensions, which are interdependently implicated in the spectrum of different countries in the world (Dreher, 2006). Economic globalization encompasses an increasing flow of goods and services, capital (portfolio investments or FDI), and labor through international trade, multinational corporations (MNCs), and migration, respectively. These components of economic globalization generate employments, increase people's income, and economic growth. In recent years, technology diffusion in information and communication technology (ICT) and transportation has facilitated the gamut of globalization in stimulating the economic growth of different economies (Pyle, 2001). Political globalization includes the international diffusion of governmental policies that relate to the development of regional trade cooperation and involvement in international agreements for larger economic integration. Besides, higher regional political integration is more likely to contribute to closer regional ties through trade chunks and it can also ease trade obstacles by securing the participation of different countries in global trade competition (Dreher, 2006; Dreher et al., 2008). Social globalization denotes the effect of globalization on people's work, life, family, and society as well and also covers the identity, culture, security, and overall cohesion among families and communities (Gunter & Van der Hoeven, 2004). Moreover, social globalization encompasses the quantity of the users and hosts of the Internet, use of telephone and mobile phones, the visa process for tourists, subscriptions of television, and sales of news dailies (Dreher & Gaston, 2008). All these components of social globalization may spur the economic growth of an economy. Thus, the economic growth of a country largely depends on the flows of economic, political, and social dimensions of globalization.

South Asian economies intend to reap the benefits of economic, political, and social globalization by introducing a globalization-friendly policy domain. The policy regime of these economies is highly concerned with maintaining trade relationships with external countries and MNCs, encouraging FDI, expanding tourism facilities for foreigners, etc. Consequently, strong local demands, an accrual in exports, and augmented inflows of FDI have pointed to this favorable position. South Asian trade diversion process is on track to be benefitted from the global economy. This area also sets itself to achieve from the experimented growth recuperation in developed economies, as these counties are the major markets for the exports of South Asian countries. Moreover, the globalization process has been facilitated by the policies of South Asian countries, and the economic growth of these countries has been stimulated by globalization. The positive influence of globalization on economic growth is favored by the empirical studies of Gurgul and Lach (2014), Ying et al. (2014), Mullings (2017), and Hasan (2019). These studies emphasized the dimensions of economic globalization, which is conducive to the economic growth of developing economies. This study finding is contradicted with Chang and Lee (2010); Ying et al. (2014); Kilic (2015); Maqbool-ur-Rahman (2015); Suci et al. (2016); Olimpia and Stela (2017); N. Wang et al. (2018) and Hasan (2019). These scholars highlighted the adverse impacts of political and social dimensions of globalization on economic growth in different developing and emerging countries.

The examined outcomes of this study also indicate that the CRI adversely impacts economic growth in the long run, and it has an adverse but insignificant effect on energy consumption in the long run in South Asian countries (Table 5). Political risk issues highly affect the quality of political, economic, and administrative institutions of any country. South Asian countries are risk-prone due to communal conflict, religious tensions, political shutdown, lockdown, etc. that impede the proper function of relevant institutions. Poor governance or weak institutional framework relating to economic activities leads to insufficient programs for industrialization, which is a hindrance to the structural transformation of an economy (Maiti, 2009). Besides, institutional quality helps accelerate privatization and make it more answerable, open, and more dedicated to secure the interest of mass people (Mukherjee & Dutta, 2018). As the inclusion of the private sector in the impressive economic growth has become a policy initiative of different governments, institution quality hence fuels the governmental policy. If there is a political risk issue, private investors and entrepreneurs can hardly invest their capital in productions. Besides, volatile state-affair is a threat to the implementation of proper regulatory mechanisms such as interest rate determination, tax enforcement, and incentives for businesses, etc. As such, South Asian countries' political spectrum witnesses an unpredictable and uncertain circumstance, though they are keeping their impressive trade relationship with external countries' mammoth investment base and faster economic growth. Because of political volatility rooted in poor institutional mechanisms, these countries' influence as major exporters of the international market might be at risk. Besides, recurring failure to allure FDI, a strong external macroeconomic determinant of growth, in apparel industries is closely associated with the politically risky environment of South Asian countries (Nabi et al., 2010). Thus, country risk issues of these countries adversely affect economic development. The study's finding of the negative role of CRI on economic development in South Asia is in line with Slaveski and Lazarov (2014); Nguyen et al. (2018) and Sekrafi and Sghaier (2018), and contradicted with Mehlum et al. (2006), and Sala-i-Martin and Subramanian (2013). These studies concluded that CRI's positive and negative magnitudes contribute to fortifying and weakening the state-owned institutions and their qualities, respectively in the context of developing economies. Thus, these empirical investigations emphasized developing institutional quality by improving the performance of CRI indicators, which can also strengthen the nexus between energy consumption and economic growth in economies.

The investigated results obtained from the short-run estimation (Table 5) show that energy consumption positively impacts economic growth, which is consistent with long-run results, and globalization adversely impacts economic growth, and it has an insignificantly negative effect on energy consumption. The CRI has an insignificantly positive impact on economic growth and a negative effect on energy consumption in the short run. On the other hand, economic growth has no significant effect on energy consumption while globalization has an insignificantly adverse influence on energy consumption in South Asian countries. The error-correction coefficients in the two models (where economic growth and energy consumption are dependent variables, respectively) show a negative and 5% level of significance as expected. It implies the short-term dynamics along with long-term co-integration and also shows the adjustment speed from any short-term disturbance to the long-term stability.

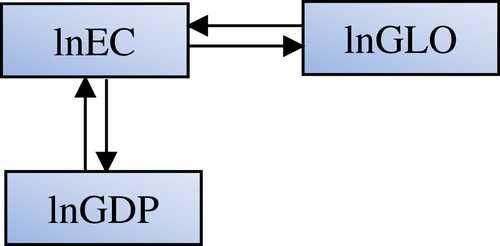

Then, the D-H non-causality test results are presented in Table 6. The causality analysis discovers a feedback hypothesis in the nexus between energy consumption (lnEC) and economic growth (lnGDP). It also implies that there is a bidirectional causal association (feedback hypothesis) between them.

| Hypothesis | W-Stat. | Zbar-Stat. | Prob. | Decision |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| lnEC → lnGDP | 2.5647 | 1.9150 | 0.0555* | Bidirectional causality between lnEC and lnGDP |

| lnGDP → lnEC | 3.6679 | 3.3196 | 0.0009*** | |

| lnGLO→ lnEC | 2.6536 | 2.0282 | 0.0425** | Bidirectional causality between lnGLO and lnEC |

| lnEC → lnGLO | 6.4992 | 6.9244 | 0.0000*** |

- Note: Symbols ***, **, and * denote significance at 1%, 5%, and at 10%, respectively.

Besides, there also exists a bidirectional causal linkage between globalization (lnGLO) and energy consumption (lnEC) in South Asian countries. The causal relationship flows among the variables are depicted in Figure 1.

Finally, the results of the panel DOLS estimation are reported in Table 7, to validate the results obtained from the PMG estimator. The estimated results depict that the signs and significance levels of the variables are similar to the results obtained from the PMG estimator, though the coefficient values are somewhat different. Overall, the study findings are robust and reliable that allow policy recommendations based on the obtained results of the study.

| Dependent variable: lnGDP | Dependent variable: lnEC | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Variable | Coefficient | SE | t-Statistic | Prob. | Variable | Coefficient | SE | t-Statistic | Prob. |

| lnEC | 0.7229* | 0.3732 | 1.9370 | 0.063 | lnGDP | 1.0421*** | 0.2285 | 4.5591 | 0.000 |

| lnGLO | 1.3605*** | 0.3465 | 3.9258 | 0.000 | lnGLO | 0.8288*** | 0.2396 | 3.4588 | 0.002 |

| CRI | −0.0712*** | 0.0244 | −2.9073 | 0.007 | CRI | −0.0033 | 0.0188 | −0.1791 | 0.859 |

| R2 | 0.9959 | R2 | 0.9993 | ||||||

| Adj. R2 | 0.9770 | Adj. R2 | 0.9953 | ||||||

- Note: Symbols *** and * denote significance at 1%, and 10%, respectively.

5 CONCLUSION AND POLICY RECOMMENDATIONS

This paper has investigated the nexus between energy consumption and economic growth in the presence of globalization and CRI in the context of South Asian countries over the period 1980–2018. The CADF and CIPS unit root tests are employed to scrutinize the stationarity of the variables of interest after checking the CD that existed in the panel data properties. We also have verified the long-run relationship among the variables utilizing the Westerlund cointegration test. The long-run and short-run associations among the variables are estimated by the PMG regression technique as this method checks the heterogeneity and cross-sectional independence in the panel data. The causal analysis is conducted using the D-H causality test. The study findings stay robust across an alternative estimator viz. the PDOLS approach as well. The findings of the study discover an energy consumption-economic growth nexus in the South Asian economies. As an exogenous indicator, globalization positively impacts this nexus whereas there is an adverse influence of CRI in these economies. Moreover, the feedback hypothesis is explored in the association between energy consumption and economic growth in South Asian economies.

From the study findings, it is evident that energy consumption and economic growth are conducive to each other in South Asia. This finding is of substantial significance for the scholars who focus on energy consumption-economic growth nexus in their studies. Under D-H non-causality test, the feedback hypothesis is established, which implies that energy consumption and economic growth are dependent on each other in South Asian economies. This also shows that an increase in one factor contributes to raising another factor in these economies. Therefore, scholars should consider the study findings while conducting further studies in the case of South Asia. Besides, the policymakers of this region have a key indication from this study finding while adopting policies regarding energy consumption and income growth. Moreover, policymakers should not restrict energy consumption that can aggravate the pace of economic growth whereas energy is considered the key component for stimulating economic growth in these economies. In addition, South Asian policymakers should also pursue pragmatic policies that encourage efficient energy consumption, modernize outdated technologies, and support clean or renewable technologies to ensure sustainable energy resources for economic growth. These will invariably spur the overall development of South Asia.

As a long-run external force, globalization positively contributes to the energy consumption-economic growth nexus in South Asia via different channels including industrialization, trade liberalization, remittances, and FDI flows. In this context, the governments of these economies should promote the process of globalization (social, economic, and political dimensions) so that it could increase the capability of people and industries to utilize energy resources for economic growth. However, modern technology diffusion for utilizing renewable or cleaner production processes should be encouraged by promoting the mechanisms of globalization, including international trade and capital flows such as FDI (economic globalization), G2G relations and participation in global forums, treaty signing (political globalization) and information flows through telephone/cellular phone purchase and usage, and the easiest visa process for tourists (social globalization). The globalization process is largely accelerated with the flows of FDI and this investment of industrialized countries is utilized for the expansion of industrial base in developing economies. To set up industries, industrial economies and their enterprises use energy-efficient production methods and green technology to enhance the process of cleaner production (Demena & Afesorgbor, 2020; M. M. Islam et al., 2021). Thus, global firms' better utilization of modern technology in comparison to developing economies' enterprises is associated with “the pollution halo hypothesis” that saves the environment of developing countries (M. M. Islam et al., 2021). From this perspective, South Asian policymakers should utilize the potentials of FDI so that cleaner production strategies can be developed while employing FDI in these countries as the significant determinant of globalization. Besides, policymakers of these economies could adopt an energy mix strategy utilizing FDI and other dynamics of globalization to continue the pace of economic growth.

Regarding the finding of the CRI, the study highlights vulnerable and uncertain politico-administrative affairs that weaken the performance of state-owned institutions and hence increase risk in energy consumption and income growth in this region. The risk in the energy-growth nexus has been intensified due to the Covid-19 pandemic in South Asian countries. Therefore, this study recommends that the risk of politico-administrative and the Covid-19 pandemic should be dealt with properly by exercising the mechanism of good governance as there is a significant adverse impact of these risk issues on the long-term energy consumption—economic growth nexus. More specifically, the policymakers of South Asian countries should fortify the institutional quality through ensuring openness in governance, controlling corruption, and improving regulatory quality. Overall, all these measures of policymakers would reinforce the energy consumption-economic growth nexus in South Asian countries.

Biographies

Md. Monirul Islam has been serving as an Assistant Professor (Governance and Public Policy) at Bangladesh Institute of Governance and Management (BIGM), the University of Dhaka (Affiliated), Bangladesh. His area of research is governance studies, energy and environmental economics, and the political economy of Bangladesh. To date, 10 research articles have been published in peer-reviewed journals at home and abroad. Furthermore, he has presented 10 conference papers at international conferences.

Md. Saiful Islam, Ph.D., is a Professor of Economics. His research interests include human development, economic growth, energy and environmental economics, microfinance, and poverty reduction. Currently, Prof. Islam works at the Department of Economics and Finance, College of Business Administration, University of Hail, Hail, Kingdom of Saudi Arabia. Md. Saiful Islam can be contacted at [email protected].

Open Research

DATA AVAILABILITY STATEMENT

The data are taken from the following three sources:

https://databank.worldbank.org/source/world-development-indicators#

https://kof.ethz.ch/en/forecasts-and-indicators/indicators/kof-globalisation-index.html

https://www.prsgroup.com/explore-our-products/international-country-risk-guide/.