Perceived public condemnation and avoidance intentions: The mediating role of moral outrage

Funding information: National Science Foundation of China, Grant/Award Number: 71573241

Abstract

The effects of intrapersonal emotion on consumers' behavior have long been studied, but the effects of interpersonal emotions on public's intentions remain poorly understood. People often get angry when they observe injustice with others but not themselves. Drawing on emotions as social information theory, we investigated how perceived public condemnation (knowledge that other also condemn a particular norm violation by an organization) affects the moral outrage of public and their future intentions toward the organization. A quantitative study was empirically examined through a sample of 107 users of a leading riding service in Pakistan. Data were analyzed through statistical tools (IBM SPSS & AMOS 21). Finding shows that perceived public condemnation was positively correlated with moral outrage and avoidance intentions of individuals. However, moral outrage mediates the association between perceived public condemnation and avoidance intentions of the public. The implications highlight the importance of a community's social norms and values to gauge the organization's reputation in people's eyes.

1 INTRODUCTION

Emotions play a key role during crisis communications and also influence the perception and behavioral intentions of the public toward an organization (Lu & Huang, 2018). The expression of emotions during the crisis for the well-being of public helps in the minimization of crisis damages, maintaining, and restoring the organizational reputation (Xiao, Hudders, Claeys, & Cauberghe, 2018). We observe emotional expression between service providers and customers on a daily basis, which shapes momentary interaction as well as intentional behaviors toward each other (Rafaeli & Miron-Spektor, 2009). Research to date has primarily focused on the basic emotions of individuals in crisis communication (Cote & Hideg, 2011). Generally, the public generates negative emotions in different ways toward a corporation in the response of unsatisfactory services or products (Van Kleef, 2010). Such as, people engage actively in negative word-of -mouth (NWOM), taking legal action, boycott the products and services, and record protest against harms made by organizations (Marin & Rubio, 2009). NWOM over different online sources negatively influence public intentions and behaviors toward an organization (Jung, Wang, Maslowska, & Malthouse, 2016; Lu & Huang, 2018).

Public protest and express moral emotions when they observe violation of normal standards, injustice and unfair behavior with workers or consumers, and have done any other ethical or social transgression (Wetzer, Zeelenberg, & Pieters, 2007; Hareli, Moran-amir, David, & Hess, 2013; Landmann, Hess, Landmann, & Hess, 2016; Van Kleef, Heerdink, & Homan, 2017). Similarly, individuals express moral outrage in the reaction of cultural or norm violation (Batson, Chao, & Givens, 2009), and unethical behaviors even they do not participate nor directly affected by the corporation's unethical behaviors (Liang, Hou, Jo, & Sarigollu, 2019). Moral outrage influences the punitive behaviors of the public toward the transgressors (Lindenmeier, Schleer, & Pricl, 2012). Actual punishment or punitive behavior toward transgressors and norm violators is essential to maintaining cooperation in a society (Konishi, Oe, Sh, Tanaka, & Ohtsubo, 2017). However, to get support for the punitive behaviors, observers must keep in view the majority opinion of the public in a community. Very smaller research has focused to investigate how the emotional expression of the public toward moral violation by an organization influence the emotions and behaviors of observers.

Research is still needed to examine how the public's emotional expression toward the norm violation of an organization influence the other observers' emotions and behavior toward that organization? Therefore, to fill this gap, this study contributes in two ways: First, we investigate how perceived public condemnation of a moral violation influence the moral outrage of other observers toward an organization. Second, we examine how moral outrage mediate the relationship between perceived public condemnation and customers' avoidance intentions.

1.1 The present study

Pakistan is considered a developing country and have a high potential to become the world's largest economies in the 21st century. The population of Pakistan has reached around 210 million making it the sixth most populous country of the world (Arifeen, 2018). Pakistan's population growth rate is 2.4% due to which the country is facing the challenges of tackling the issues of economic development and poverty reduction (Afzal, 2009; Ahmed & Ahmad, 2016). However, research reveal that a country's large population positively influence the foreign investment decision (Aziz & Makkawi, 2012) because large population provide a large market for products and services offered by the multinational companies. Similarly, Pakistan is a land of opportunity, and many potential investors and businessmen are interested to grab the market by investing in the country.

Thus, to grab the market, Careem an Emirati transportation networking company based in Dubai started its services in Pakistan in 2015 (Malik, 2019). Careem was launched in 2012 in Dubai, and in short years, they expanded to 100 cities in 14 countries in the Middle East, Africa, and South Asia (Kamran, Rehman, Chaudhri, & Farrukh, 2019; Stephens, 2019). Currently, Careem provides its ride-hailing services in the few big cities of Pakistan such as Karachi, Islamabad, Lahore, Faisalabad, and Peshawar. The service is popular among Pakistan's urban class for their smart technology, door-to-door services, and affordability. But, Due to few incidents e.g. kidnapping attempts, moral violation and the rude behaviors by the captains of Careem ride-hailing services have negatively influenced the customers' intentions., (Dawn, 2018). Therefore, in this study, we choose a case in which a captain of Careem ride-hailing services recorded himself on video hurling abuses at and threatening a customer with violence when the passenger lit a cigarette inside the car and then threw the cigarette onto the car's floor mat. Soon after the incident, and sharing the video on social media, it attracted wide public attention, and people posted different comments on social media to charge emotion, condemn the captain's behavior, and show their intentions toward hiring Careem's services in future.

2 LITERATURE REVIEW AND HYPOTHESIS BUILDING

The Situational Crisis Communication Theory described that people attribute the responsibility of crisis in the light of previous crisis history, responsibility, and prior relationships with stakeholders (Coombs, 2004, 2007). The attribution of crisis responsibility and unsatisfactory services or products generates negative emotions in people, which ultimately lead them to take legal action, boycott the products, or spread NWOM about the organization (Lu & Huang, 2018; Marin & Rubio, 2009). Similarly, negative emotions reduce the positive intentions of people toward the organization (Jung et al., 2016; Lu & Huang, 2018). However, people not only retaliates injustice and unfairness done to oneself but also show negative emotions to the injustice being done to others (Fehr & Fischbacher, 2004). Yet, to our best knowledge, in the context of crisis communication, no theoretical sound model exists for analyzing that how people perceive or assess the emotions of others through which they subsequently generate different emotions toward an organization.

Emotion plays a pivotal role in coordinating social life, and it had been studied extensively in the context of intergroup relationships. However, researchers have recently started to study the role of emotions in the maintenance of group's social norms and the promotion of coordination among its members to get a common goal (Spoor, Jetten, & Hornsey, 2004). For the development of human cooperation, strong reciprocity is needed in which people have a feeling for unconditional cooperation and altruistic punishment against norm violators. Individuals experience negative emotions such as guilt, anger, desire for revenge, and to fight with the norm violators (Sun, Tan, Cheng, Chen, & Qu, 2015). The emotional reaction to injustice on behalf of others promotes social behavior (Haidt, 2001; Nelissen & Zeelenberg, 2009). Public express different emotions as a result of their conscious or unconscious assessment of some events relevant to a particular aim or concern in order to regulate the observers' behaviors (Fischer & Manstead, 2016), which contribute to the interpersonal behavior regulation (Kleef, 2016; Van Kleef & Heerdink, 2015). Previous research focused on the intrapersonal effect of emotion that how an individual's effective system influences his own cognition, motivation, and behaviors. But, in recent studies of emotions, social psychologists explained that emotional expression also affects the others' (observers) feelings, attitudes, relational orientation, and behavioral intentions at the interpersonal level (Elfenbein, 2007; Van Kleef, 2016).

According to EASI theory, emotions expression regulates social and organizational life by provoking effective and cognitive implications in observers (Van Kleef & Fischer, 2016). Moreover, EASI also described the function of emotions expressed in decision making, social influence, and organizational behaviors. Similarly, in the organizational perspective, observers (third party) evaluate the reactions of organizational authorities toward consumers, on behalf of which they shape their behavior and attitudes toward the organizations. Many factors including economic interests, past experience, and personal relationships with decision addresses influence the third party's emotions and judgment (Blader, Wiesenfeld, Fortin, & Wheeler-smith, 2013).

The emotional expression of public affect the observers' emotions in two different mechanisms such as effective reaction and cognitive inferences (Giner-sorolla & Espinosa, 2015; Heerdink, Van Kleef, Homan, & Fischer, 2013). According to social psychology research, in the emotion perception, individuals rapidly and automatically processing others' emotions in order to produce emotional reaction accordingly (Smortchkova, 2016). In this study, we examine the expression of moral outrage toward the norm violation by an organization's work from a third party perspective. Moreover, because of the third party's emotional reaction to norm violation, the public can learn about the norms and values of a community (Van Kleef, Heerdink, Koning, & Van Doorn, 2018). Past research reveals that moral violation evokes different negative emotions among the people (Cameron, Lindquist, & Gray, 2015; Landmann & Hess, 2017).

2.1 Perceived public condemnation

Condemnation refers to disliking the act, the way of thinking, and lack of feeling, which led individuals toward transgression in a society (Lamb, 2003). Condemnation can be defined as the negative evaluation of an individual's character and behaviors and wish to penalize him or deprive him of rewards on behalf of his/her norms violation (Effron, Lucas, & Connor, 2015). Research reveals that public evokes moral condemnation when there has been an invasion onto a community's standard norms. For example, people strongly condemn harmless sexual taboo behaviors although both the agents (brother and sister) agreed upon consensual and safe sex (Mooijman & Van Dijk, 2014). However, the protection of social standard and self-integrity motivate people to feel disgusted and strongly condemn the harmless sexual taboo behaviors (Mooijman & Van Dijk, 2014; Schnall, Clore, & Jordan, 2008). Similarly, when the violation of moral standard cause huge harm and is highly noticeable, people may strongly condemn it, whereas the low degree of negative outcomes of a moral violation attenuates moral condemnation (Wiltermuth, Vincent, & Gino, 2017).

People express moral condemnation on the basis of different categories of moral violation such as harm/care, fairness/justice, in-group/loyalty, authority/respect, and purity/sanctity (Haidt & Graham, 2007). Similarly, condemnation sometimes gives authoritative approval to the community's members to express moral outrage and punitive behaviors toward the transgressors of social norms and values (Lamb, 2003). An individual's anger expression increases when he/she directly affects the moral violation while his/her condemnation decreases. On the other hand, condemnation of a moral violation increases and anger decreases when its target shifts from one's self to another person (Molho, Tybur, Güler, Balliet, & Hofmann, 2017).

Fear of isolation led public to take a punitive decision and evoke negative moral emotions toward transgressors, which are consistent with the perceived decisions/behaviors of other members of a community (Konishi et al., 2017; Zheng, Liu, & Davison, 2018). An individual will express moral emotions toward transgressors based on his/her knowledge about the opinion of the majority of the public in the community (Szolnoki, 2013). Therefore, we assume that:

H1a..Perceived public condemnation of a norm violation in a community is positively associated with the moral outrage toward norm violation.

H1b..Perceived public condemnation of a norm violation in a community is positively associated with the avoidance intentions.

2.2 Moral outrage

Moral emotions affect the moral judgments and behaviors of the public (Ward & King, 2017) and play a pivotal role in sustaining the social and moral standards in a society (Prinz & Prinz, 2007). However, research shows that emotions that are directed toward others for violating the moral standard norms and values are known as moral outrage (Haidt, 2001; Hechler & Kessler, 2018). People express moral outrage on behalf of the victims of a moral violation, to compensate them and punish the social transgressors (Rothschild & Keefer, 2017). Moral emotions can be defined as the emotional response of the public to moral violations and standards, which influence the moral behavior of an individual (Haidt, 2001). However, prosocial behaviors refer to the behaviors of individuals that provide benefits or increase the welfare of others (Penners, Dovidio, Piliavin, & Schroeder, 2004).

Observing injustice with others also elicits anger in observers, which is known as moral outrage (Rothschild, Landau, Molina, Branscombe, & Sullivan, 2013). Moral outrage motivates observers to punish the harm-doer (Pagano & Huo, 2007). Psychologists have differentiated moral outrage from the anger. The first one refers to the anger that results from observing the transgression of moral standards or injustice behavior with another person or group and which does not affect the self (Fehr & Fischbacher, 2004; Van De Vyver & Abrams, 2014). Moral outrage is a reaction to the circumstances in which a person violates the ethical values and standards of a community (Rushton, 2013). Moral emotions are perceived prevalent and powerful (Mara, Jackson, Batson, & Gaertner, 2011), which influence individuals' moral judgments and intentional behaviors towards transgressors and victims (Cheng, Ottati, & Price, 2013; Thulin & Bicchieri, 2016). Therefore, we propose that the expression of moral outrage will mediate the relationships between perceived public condemnation and avoidance intentions.

3 METHODOLOGY

3.1 Measurement

To test our study, we adapted a scale from the previous studies. Perceived public condemnation was assessed with three items on a 5-point Likert scale from 1 (not at all) to 5 (extremely condemn). The items were adapted from the study of Mooijman and Dijk (2014) and Konishi et al. (2017). Items include the following: to what extent do you think that the public has morally condemned, perceived morally wrong, and morally accepted the captain's behavior with his customer? To measure the moral outrage of participants, a 4-item scale was modified from the study of Constant and B. (2012). Example item includes the following: I feel sad, angry, bother, and concerned when I read about/watched the captain's behavior with his customer. The items were measured on a 5-point Likert scale from strongly disagree to strongly agree. Similarly, a 3-item scale was adapted from the study of Xiao et al. (2018) and Bowen, Freidank, Wannow, and Cavallone (2018) to measure the users' avoidance intentions of using the services in the future. Example items include the following: (a) I will not use any services from Careem in future, (b) I want to keep as much distance as possible between Careem's services and myself, and (c) I will advise my friends and relatives to avoid hiring Careem's services in the future.

3.2 Participants and recruitment

Data were collected through snowball sampling technique. A total of 130 respondents were invited from three cities including Islamabad, Lahore, and Peshawar in Pakistan, where the Careem cabbing services is available. After inviting the participants, we sent them a questionnaire in Urdu language and were provided a video link and news story regarding the behavior of Careem's captain with his customer as supportive materials. We received 120 responses in which 107 were selected as valid for our research study. After collecting the data, we analyzed it with the following techniques. First, with the descriptive analysis, we find the demographic information of the respondents and second, we performed exploratory factor analysis to examine the factors loading. Third, we used a structural equation model for the model test and PROCESS Macro for SPSS for the mediation analysis to examine how moral outrage mediate the relationships between perceived public condemnation and avoidance intention.

Out of 107 participants, 47 (43.9%) were male, whereas 60 (56.1%) were female. In addition, 75 (70.1%) were single, whereas 32 (29.9%) were married. Among the 107 participants, 79 (73.8%) were less than 25 years, 24 (22.4%) were the age of between 26–35 years, two (1.9%) were 36–45, whereas 2 (1.9%) were above the age of 45 years. Similarly, 17 (15.9%) had college level education, 63 (58.9%) had bachelor, and 27 (25.2%) had master education. Demographic information was based on gender, age, education, profession, monthly family income, and family members as shown in Table 1.

| Category | Frequency | Percentage (%) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Gender | Male | 47 | 43.9 |

| Female | 60 | 56.1 | |

| Marital status | Single | 75 | 70.1 |

| Married | 32 | 29.9 | |

| Age | Less than 25 | 79 | 73.8 |

| 26 to 35 | 24 | 22.4 | |

| 36 to 45 | 2 | 1.9 | |

| Above 45 | 2 | 1.9 | |

| Education | College level | 17 | 15.9 |

| Bachelor's degree | 63 | 58.9 | |

| Master's degree and higher | 27 | 25.2 | |

3.3 Exploratory factor analysis

We used exploratory factor analysis to find out if the factor loading (FL) of each item observed above the lower cut-off value of 0.4 which also observed to hold no cross-loading effect and were recommended for the further analysis (Hair, Black, Babin, & Anderson, 2010). We performed EFA by using the principal components method with varimax rotation and suppress values less than .50. Table 2 shows the FLs of all items. All FLs are in the range of .648 and .906, whereas the recommended values should be substantial and exceed .7. We also checked the average variance extracted (AVE) to ensure items' reliability and convergent validity. All of the AVE values were between the .53 and .78, which shows that the items fulfilled the convergent validity requirements. To measure the reliability of constructs, we used composite reliability and Cronbach's alpha values. Values of composite reliability were between .82 and .91, and for Cronbach's alpha, the values show between .76 and .90. Thus, all the items were reliable and valid as shown in Table 2. Discriminant validity was assessed by comparing the square root of AVE for each variable with the interconstruct correlations. The values of the square root of AVE for each variable are greater than those for all related interconstruct connections. Therefore, the discriminant validity of all scales is acceptable, as shown in Table 3.

| Variables | Items | Factor loading | Cronbach's alpha | AVE | CR |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Perceived public condemnation (PPC) | PPC1 | .886 | .900 | .78 | .91 |

| PPC2 | .905 | ||||

| PPC3 | .861 | ||||

| Moral outrage (MO) | MO1 | .742 | .763 | .53 | .82 |

| MO2 | .822 | ||||

| MO3 | .698 | ||||

| MO4 | .648 | ||||

| Avoidance intentions (AI) | AI1 | .793 | .843 | .71 | .88 |

| AI2 | .906 | ||||

| AI3 | .831 |

- Abbreviations: AVE, average variance extracted; composite reliability.

| Correlations | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean (SD) | 1 | 2 | 3 | |

| 1. PPC | 4.3 (.836) | (.88) | ||

| 2. MO | 4.2 (.584) | .449** | (.73) | |

| 3. AI | 3.1 (.586) | .285** | .343** | (.84) |

- ** Correlation is significant at the .01 level (two-tailed).

- * Correlation is significant at the .05 level (two-tailed).

- Abbreviations: PPC, perceived public condemnation; MO, moral outrage; AI, avoidance intentions.

Furthermore, the structural model was tested for the validated measures by using IBM AMOS 21. The overall fitness indices for the confirmatory factor analysis (CFA) are within the accepted range. The value of CMIN/df recorded as 1.65, which is within the accepted range of CMIN to be ranged between 1 and 3 (Hooper, Coughlan, & Mullen, 2008). Moreover, the satisfied fitness indices include the absolute (GFI and AGFI), relative (NFI, IFI, and TLI), and non-centrality indices (RMSEA and CFI) as shown in the table 5 (Gerbing & Anderson, 1992). Specifically, the preferred value of GFI and AGFI noted as >.90 (Hooper, Coughlan, & Mullen, 2008), whereas in the present analysis, GFI is .92 and AGFI observed as .90, which support the previous literature (Hair et al., 2010). Moreover, values of NFI as .92, IFI as .96 and TLI as .95 were recorded. Values of RSMEA and CFI are .076 and.96, respectively. The finding supports previous literature that both values of RSMEA and CFI should be <.08 and >.90, respectively (Anderson et al., 1988). Therefore, the outcomes show a valid model fit.

3.4 Correlation

Table 3 presents the means, standard deviations (SD), and bivariate correlation results of the study variables including perceived public condemnation, moral outrage, and avoidance intentions. Perceived public condemnation has a positive correlation with the moral outrage (.449**, p = <.01), which suggest that perceived public condemnation plays a critical role in influencing the moral outrage of public toward the moral violators in a community. In addition, perceived public condemnation significantly correlates with avoidance intentions (.285**, p = <.01). Moreover, moral outrage also significantly correlated with the avoidance intentions (.343**, p = <.01).

3.5 Mediation analysis

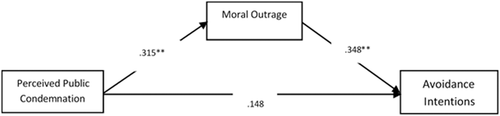

PROCESS macro (Model 4) for SPSS was used to identify the significance of direct, indirect, and total effects in a mediation model based on 95% bootstrap confidence interval with 5,000 bootstrap samples. In Step 1 of mediation model, the perceived public condemnation had significant relationships with moral outrage (b = .315, t(105) = 5.14, p = <.01) which supported H1(a). Similarly, Step 2, showed that perceived public condemnation had significant effects on avoidance intentions (b = .257, t(105) = 3.045, p = <.01). The findings support H1(b). In Step 3, the mediation process showed that moral outrage had significant effect on avoidance intentions (b = .348, t(104) = 2.65, p = <.01). In addition, Step 4 of the mediation model showed that controlling the mediator (moral outrage), the perceived public condemnation had no significant effect on avoidance intentions (b = .148, t(104) = 1.60, p = n.s). Overall, our findings showed that moral outrage fully mediated the relationships between perceived public condemnation and public avoidance intentions as shown in Table 4. Figure 1 shows the structural equation modeling with a beta coefficient and level of significance.

| Co-efficient | SE | t | p value | LLCI | ULCI | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| PPC → AI | .257 | .084 | (105) = 3.04 | .002** | .0900 | .4257 |

| PPC → MO | .315 | .061 | (105) = 5.146 | .000** | .1935 | .4362 |

| MO → AI | .348 | .131 | (104) = 2.65 | .009** | .0879 | .6087 |

| PPC → MO → AI | .148 | .092 | (104) = 1.60 | .111 | −.0345 | .3309 |

| Direct effect | .148 | .092 | −.0345 | .3309 | ||

| Indirect effect | .110 | .052 | .0285 | .2362 |

- Note. Confidence intervals is 95% bootstrap confidence interval; bootstrap based on 5,000 bootstrap samples.

- Abbreviations: PPC, perceived public condemnation; MO, moral outrage; AI, avoidance intentions.

- * p < .05.

- ** p < .01.

4 DISCUSSION

The purpose of this study was to examine the influence of interpersonal emotions on the avoidance intentions of the public toward an organization. To support our model, we conducted our study in the context of moral violation in Pakistan. The results supported our study and offer important theoretical and practical implications. Overall, our study results supported the research model and hypothesis.

Our results are in line with the past research suggesting that perceived public condemnation has a positive impact over the moral outrage of observers toward the norm violators. The findings supported previous studies that public will show more moral emotions toward the moral violation of an organization when they expect that others would also condemn it (Konishi et al., 2017). Many people openly condemn the moral violation in a community, which helps in generating emotional expression on the interpersonal level (Van Kleef & Fischer, 2016). The emotional expression can evoke affective, cognitive, and behavioral responses in observers (Kleef, 2016).

Moral outrage is a major trigger that affects the positive intentional behaviors of the public toward norm violators (Lindenmeier et al., 2012). The results of our study supported the previous literature that moral outrage influences positively the avoidance intentions of the public toward the organization. Our findings are consistent with the previous study of Grappi, Romani, and Bagozzi (2013), indicating that consumers' negative emotions lead them toward NWOM and protest behaviors.

The study has some theoretical implications: this study adds to the current literature on the role of emotions in influencing the customers' behavioral intentions. Similarly, the study extends the emotion as information theory in the context of customers' avoidance intentional behaviors. This implication of theory provides considerable and interesting insight to understand the customers' adverse intentions toward the online cabbing services. Moreover, the study highlights that people's emotional reaction as a result of conscious or unconscious assessment of an event or injustice with others regulates their organizational behaviors. To the best of our knowledge, this is the first study to gauge the effect of interpersonal emotions on consumers' avoidance intentions. More interestingly, the study emphasizes on the mediation effect of moral outrage on the relationships between perceived public condemnation and avoidance intentions. Overall, the study shows that people's emotional reactions to moral violation influence the observers' avoidance intentions toward an organization.

In practical implications, the findings of this study indicate that the emotional expression of the public can serve as a source of information for the organization during a crisis situation that may help the professionals to gauge the organization's reputation and quality of services in the public's eyes. Therefore, an organization should be aware of the importance of a community's social norms and values. In addition, the organization should have a direct check on their workers (team) as well as on public through social media in order to avoid negative consequences and reputational threats in the future. The organization needs to arrange/conduct training and seminars for its workers on how to deal with the public and improve relationships with them. Similarly, organizations also need to educate their customers through different media outlets regarding their rules and ethics. On the other hand, the public should take preprotective steps to avoid any type of uncertainties.

4.1 Limitation and future directions

Our study has several limitations. First, we found that perceived public condemnation affect moral outrage, but individuals can also get angry by observing moral violation directly. Future studies need to find out how moral violation elicits negative emotions such as anger, disgust, condemnation, etc. toward the norm violators. Second, people often express emotions that change over time. Literature suggests that changing emotions generate different inferential processes, affective reactions and behavioral intentions (Heerdink et al., 2013). It is interesting to examine how the public may react to such dynamic emotional expression, which changes in response to relevant norm violation. Third, we found the emotional reaction and intentions of the public only. However, a full picture of emotional reaction and intentional behavior to norm violation on both sides (public and organization's team) is needed. A number of factors such as the nature of relationships with norm violators or with victims influence the emotional responses and behavioral intentions of the public. Future studies should address these factors on how one's kin, social exchange partner, friends, mates, or group memberships affect the emotional reaction and intentional behavior of the public toward norm violations. Fourth, the study only focused on one type of norm violation (abuses the customers). Future research needed to determine how other transgressions such as robbery, cheating, sexual harassment, lying, etc. influence the emotional response and behavioral intentions of the public toward an organization. Finally, we collected data only from one country (Pakistan), but people in a different culture may experience emotions differently or at different frequencies toward norm violations. Future research needed to conduct a cross-cultural study on the emotional responses and behavioral intentions of public toward norm violations.

5 CONCLUSIONS

This research study highlights the effects of perceived public condemnation and moral outrage on public avoidance intentions. The study also contributes to the existing literature on the social influence of emotions. Emotional expressions shape social influence by affecting the behaviors, attitudes, and emotions of observers. Specifically, emotion functions are influencing the consumers' behavior during an organizational crisis. This study lends strong support to the literature that knowledge about the emotions of others in a community influences the emotional responses and intentional behaviors of the public toward an organization due to norm violations.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

This research was supported by the National Science Foundation of China (NSFC No. 71573241) and CAS-TWAS President's Fellowship Program.

Biographies

Zakir Shah is a Ph.D. student in the Department of Science & Technology Communication and policy, School of Humanities and Social Sciences, University of Science and Technology of China, Hefei, Anhui, China. He is supported by the CAS-TWASPresident's Fellowship program. His research areas include Media and Humanbehaviors, Media effects (psychological impacts of media) and Crisis communication.

Jianxun Chu is a Ph.D. University of Science and Technology of China, 2006) is a professor and Vice Dean of School of PublicAffairs, University of Science and Technology of China (USTC). His research focuses on the impact of Social Media, Social Networks and Transactive MemorySystems in the fields of Innovation Diffusion, Science Communication and CrisisCommunication based on Big Data and modeling simulation of System Dynamics. Heis the PI of several projects by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (NSFC#71573241), Chinese Academy of Sciences(CAS), and China Association for Science and Technology(CAST).

Sara Qaisar is a Ph.D. student in the Department of Science & Technology Communication and Policy, School of Humanities and Social Sciences, University of Science and Technology of China, Hefei, Anhui, China. She is supported by the CAS-TWAS President's Fellowship program.

Zameer Hassan is a Ph.D student in the Department of Science & Technology Communication and Policy, School of Humanities and Social Sciences, University of Science and Technology of China, Hefei, Anhui, China.

Usman Ghani is a Ph.D. student in the School of Management Sciences, University of Science and Technology of China. He has completed his M. Phil from the Hazara University, Mansehra Pakistan.