Two-year effect of semaglutide 2.4 mg on control of eating in adults with overweight/obesity: STEP 5

Funding information: Novo Nordisk, A/S

Abstract

Objective

This study evaluated the effect of once-weekly semaglutide 2.4 mg on 2-year control of eating.

Methods

In STEP 5, adults with overweight/obesity were randomized 1:1 to semaglutide 2.4 mg or placebo, plus lifestyle modification, for 104 weeks. A 19-item Control of Eating Questionnaire was administered at weeks 0, 20, 52, and 104 in a subgroup of participants. P values were not controlled for multiplicity.

Results

In participants completing the Control of Eating Questionnaire (semaglutide, n = 88; placebo, n = 86), mean body weight changes were −14.8% (semaglutide) and −2.4% (placebo). Scores significantly improved with semaglutide versus placebo for Craving Control and Craving for Savory domains at weeks 20, 52, and 104 (p < 0.01); for Positive Mood and Craving for Sweet domains at weeks 20 and 52 (p < 0.05); and for hunger and fullness at week 20 (p < 0.001). Improvements in craving domain scores were positively correlated with reductions in body weight from baseline to week 104 with semaglutide. At 104 weeks, scores for desire to eat salty and spicy food, cravings for dairy and starchy foods, difficulty in resisting cravings, and control of eating were significantly reduced with semaglutide versus placebo (all p < 0.05).

Conclusions

In adults with overweight/obesity, semaglutide 2.4 mg improved short- and longer-term control of eating associated with substantial weight loss.

Study Importance

What is already known?

- It has previously been shown that semaglutide is effective in reducing body weight and has favorable short-term effects on aspects of control of eating such as hunger and fullness, food cravings, and mood in people with overweight or obesity.

What does this study add?

- We have demonstrated that, over a longer duration of 104 weeks, semaglutide 2.4 mg improved participants' ability to control their eating and made it easier to resist food cravings compared with placebo.

How might these results change the direction of research or the focus of clinical practice?

- The availability of semaglutide 2.4 mg represents an effective longer-term treatment for overweight or obesity by improving the control of eating and food cravings, which enables patients to achieve and maintain substantial weight loss.

INTRODUCTION

In people with obesity, losing ≥5% body weight is recommended to prevent or improve weight-related health complications [(1, 2)]. However, this can be difficult to achieve through diet and exercise alone because of compensatory changes in appetite-regulating hormones, which act to maintain normal weight homeostasis (also known as metabolic adaptation) [(3)]. An increase in the orexigenic hormone ghrelin can occur in response to weight loss, as can decreases in anorexigenic hormones, such as leptin, glucagon-like peptide-1, cholecystokinin, and peptide YY. These changes may lead to increased feelings of hunger and reduced satiety, often resulting in weight plateau and/or regain [(3)], highlighting the need for adjunctive treatment that will reduce appetite and control overeating in persons with overweight/obesity who lose weight.

The once-weekly, subcutaneously injected glucagon-like peptide-1 receptor agonist semaglutide 2.4 mg is approved as an adjunctive treatment to lifestyle recommendations to achieve and maintain weight loss in people with overweight/obesity [(4)]. Preclinical studies indicate that semaglutide can access areas of the brain involved in appetite regulation, suggesting the involvement of the central nervous system in semaglutide-induced weight loss [(5)]. Furthermore, semaglutide caused weight loss in rodents without decreasing energy expenditure, through effects on both homeostatic (appetite, hunger, satiety) and hedonic (food choice, control) neural pathways [(5)].

In clinical studies of up to 20 weeks in duration, semaglutide has been shown to lower body weight by improving aspects of control of eating, including reducing appetite, food cravings, and energy intake in participants with obesity [(6, 7)]. However, the longer-term effects of semaglutide, particularly in the face of substantial weight loss, are unknown.

The Semaglutide Treatment Effect in People with obesity (STEP) 5 trial investigated longer-term weight management with semaglutide 2.4 mg versus placebo over 104 weeks. Overall, mean changes in body weight from baseline to week 104 were −15.2% with semaglutide versus −2.6% with placebo (estimated treatment difference of −12.6 percentage points; 95% confidence interval [CI]: −15.3 to −9.8; p < 0.0001) (ClinicalTrials.gov identifier NCT03693430) [(8)]. The trial included the Control of Eating Questionnaire (CoEQ) as an exploratory end point in a subpopulation of participants to assess the intensity and type of food cravings, as well as subjective sensations of appetite, hunger, fullness, and mood.

The present study evaluated short- and longer-term changes in CoEQ scores for semaglutide 2.4 mg versus placebo as an adjunct to lifestyle intervention and assessed the effects of baseline craving domain, hunger, and fullness scores on weight loss at week 104.

METHODS

Trial design

The design and full eligibility criteria of the 104-week, phase 3, double-blind, randomized, placebo-controlled, multicenter STEP 5 trial have been published previously [(8, 9)]. The protocol was approved by independent ethics committees or institutional review boards at each study site, and the trial was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and Good Clinical Practice guidelines. Investigators were responsible for data collection, and the sponsor undertook site monitoring, data collation, and analysis.

In brief, STEP 5 enrolled 304 adults with body mass index (BMI) ≥30 kg/m2, or ≥27 kg/m2 with ≥1 weight-related comorbidity, but without diabetes. All participants were randomly assigned 1:1 to receive 104 weeks of treatment with once-weekly subcutaneous semaglutide 2.4 mg or placebo, plus lifestyle intervention (a 500-kcal deficit per day relative to the estimated total energy expenditure at randomization and 150 minutes of physical activity per week). Participants were counseled by a dietitian or similar health care professional every fourth week via in-clinic visits or phone contact. Semaglutide was initiated at 0.25 mg once weekly and escalated every 4 weeks to reach the maintenance dose of 2.4 mg once weekly at the end of week 16 (±3 days visit window). Lower maintenance doses were permitted if participants were unable to tolerate 2.4 mg.

Co-primary end points were percentage change in body weight from baseline to week 104 and achievement of body weight reduction of ≥5% from baseline to week 104. Secondary end points included achievement of body weight reduction of ≥10%, ≥15% (confirmatory), and ≥20% (supportive) from baseline to week 104. Participant-reported control of eating was evaluated as an exploratory end point in a subset of trial participants, which for logistical reasons included all those residing in the United States and Canada (n = 174). A 19-item version of the CoEQ was used to assess control of eating [(10)].

-

Craving Control (all items in this domain are reversed, such that a greater score represents a greater level of craving control)

- How often food cravings have been

- How strong cravings have been

- How difficult it is to resist cravings

- How often you have eaten in response to cravings

- How difficult it is to control your eating

-

Positive Mood

- How happy have you felt?

- How anxious have you felt? (Item reversed)

- How alert have you felt?

- How contented have you felt?

-

Craving for Savory

- Desire to eat salty and spicy food

- Cravings for dairy food

- Cravings for starchy foods

- Cravings for salty and spicy foods

-

Craving for Sweet

- Desire to eat sweet food

- Cravings for chocolate

- Cravings for sweet food

- Cravings for fruit or fruit juice

- How hungry have you felt?

- How full have you felt?

Participants were given the opportunity to complete the questionnaire by themselves without interruption, based on their experience over the previous 7 days. The questionnaire was available in a linguistically validated translated version and took approximately 10 minutes to complete.

The CoEQ was administered at baseline and at weeks 20, 52, and 104. In addition, post hoc analyses explored (1) the association between changes in CoEQ domain scores and body weight and (2) body weight changes in subgroups of participants categorized according to whether their baseline scores were less than the mean baseline score or were greater than or equal to the mean baseline score in the total population for the Craving domain and for items of hunger and fullness. In order to further explore potentially meaningful subgroups, a cluster analysis was performed post hoc on the mean scores at baseline for each item in the CoEQ.

Statistical analysis

Efficacy end points in STEP 5 were analyzed using the full analysis set (all randomized participants according to the intention-to-treat principle). Full details of the statistical analyses performed in STEP 5 have been reported elsewhere [(8)].

In the present analysis, data from all participants in the STEP 5 trial who completed the CoEQ were included. All reported results are for the treatment policy estimand (treatment effect regardless of treatment discontinuation or rescue intervention), unless stated otherwise [(11)].

For domain scores, the sum of the items in each domain was calculated and divided by the number of items in the domain. In order for a domain score to be derived, at least 50% of the included items needed to be answered. Responses for the CoEQ were analyzed using ANCOVA, with randomized treatment as a factor and baseline value of the respective item or domain as a covariate. For the post hoc analyses of weight loss by baseline craving domain, hunger, and fullness scores, week 104 responses were analyzed using ANCOVA with randomized treatment as a factor and baseline body weight as a covariate. A multiple imputation approach was used, in which missing data were imputed by sampling from available measurements at week 104 from participants in the same treatment group.

The cluster analysis was done using Ward's minimum-variance method [(12)], and the number of clusters sought was identified using standard criteria (cubic clustering criterion, pseudo F, and pseudo t-squared).

As change in CoEQ scores was an exploratory end point in STEP 5, analyses were not controlled for multiple comparisons.

RESULTS

Participants

In total, 174 participants from the STEP 5 trial completed the CoEQ (semaglutide 2.4 mg, n = 88; placebo, n = 86). The demographic and baseline characteristics of these participants are shown in Table 1 and Supporting Information Table S1. The majority were female (77.6%) and White (88.5%); the mean (standard deviation [SD]) age was 47 (11) years and body weight was 106.5 (23.6) kg. High proportions of participants in the CoEQ population completed the trial on treatment and attended the end-of-trial visit (Supporting Information Table S2).

| Semaglutide 2.4 mg, N = 88 | Placebo, N = 86 | Total, N = 174 | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age, y | 47.3 (12.3) | 47.3 (10.7) | 47.3 (11.5) |

| Female, n (%) | 71 (80.7) | 64 (74.4) | 135 (77.6) |

| Race or ethnic group, n (%)a | |||

| White | 77 (87.5) | 77 (89.5) | 154 (88.5) |

| Black or African American | 7 (8.0) | 5 (5.8) | 12 (6.9) |

| American Indian or Alaska Native | 2 (2.3) | 1 (1.2) | 3 (1.7) |

| Asian | 2 (2.3) | 0 | 2 (1.1) |

| Other | 0 | 3 (3.5) | 3 (1.7) |

| Hispanic or Latino ethnic group, n (%) | 9 (10.2) | 10 (11.6) | 19 (10.9) |

| Body weight, kg | 107.0 (20.8) | 105.9 (26.2) | 106.5 (23.6) |

| BMI | |||

| Mean, kg/m2 | 39.3 (6.9) | 38.1 (7.9) | 38.7 (7.4) |

| Distribution, n (%) | |||

| <30 kg/m2 | 2 (2.3) | 2 (2.3) | 4 (2.3) |

| ≥30 to <35 kg/m2 | 25 (28.4) | 37 (43.0) | 62 (35.6) |

| ≥35 to <40 kg/m2 | 28 (31.8) | 19 (22.1) | 47 (27.0) |

| ≥40 kg/m2 | 33 (37.5) | 28 (32.6) | 61 (35.1) |

| Waist circumference, cm | 116.3 (13.9) | 114.7 (16.2) | 115.5 (15.1) |

| Control of Eating Questionnaire domain scores | |||

| Craving Control | 4.6 (2.4) | 5.0 (2.4) | 4.8 (2.4) |

| Positive Mood | 7.4 (1.4) | 7.5 (1.3) | 7.5 (1.3) |

| Craving for Savory | 4.9 (2.1) | 5.0 (2.2) | 5.0 (2.1) |

| Craving for Sweet | 4.5 (2.1) | 4.3 (2.3) | 4.4 (2.1) |

| Control of Eating Questionnaire individual item scores | |||

| How hungry have you felt? | 5.5 (2.0) | 5.8 (1.9) | 5.6 (1.9) |

| How full have you felt? | 6.3 (2.0) | 5.9 (1.9) | 6.1 (2.0) |

- Note: Data are mean (SD) unless otherwise stated. Percentages are based on number of participants. The last available and eligible observation at or prior to the randomization visit was selected for summary.

- a Race and ethnic group were reported by the investigator. The category of “other” includes any other ethnic group.

Change in body weight

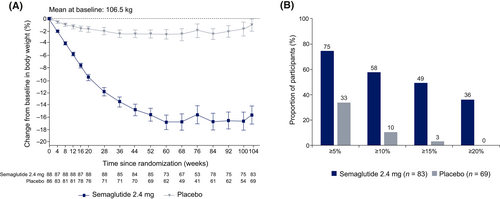

Mean observed change in body weight over time in participants who completed the CoEQ is shown in Figure 1A. The estimated mean change in body weight from baseline to week 104 was −14.8% with semaglutide 2.4 mg and −2.4% with placebo (estimated treatment difference, −12.4 percentage points; 95% CI: −16.2 to −8.5; p < 0.0001).

From baseline to week 104, numerically larger proportions of participants in the semaglutide treatment group than in the placebo group achieved a weight loss of ≥5% (74.7% vs. 33.3%), ≥10% (57.8% vs. 10.1%), ≥15% (49.4% vs. 2.9%), and ≥20% (36.1% vs. 0.0%) (Figure 1B).

Short- and longer-term changes in CoEQ scores

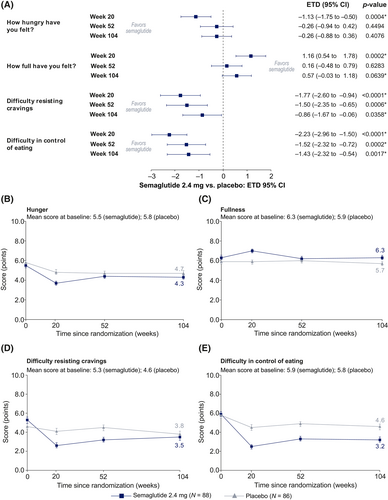

Change from baseline to week 20, week 52, and week 104 for the four domains

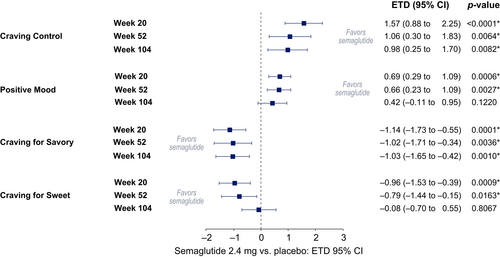

The Craving Control and Craving for Savory domain scores were significantly improved with semaglutide versus placebo from baseline to weeks 20, 52, and 104 (p < 0.01); Positive Mood and Craving for Sweet domain scores were significantly improved with semaglutide versus placebo at weeks 20 and 52 (p < 0.05) but were not statistically significant at week 104 (Figure 2).

Association between changes in body weight and the four domains from baseline to week 104

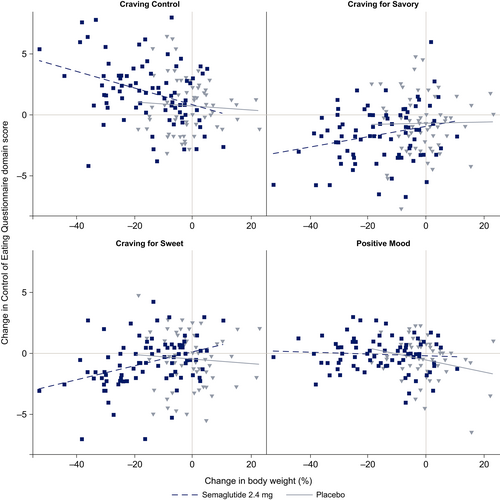

In post hoc analyses, improvements in the three craving domains (Craving for Sweet, Craving for Savory, and Craving Control) were positively correlated with reductions in body weight from baseline to week 104 with semaglutide. There did not appear to be any association between the Positive Mood domain and change in body weight with semaglutide. No correlations were observed for any craving domain in the placebo treatment group (Figure 3).

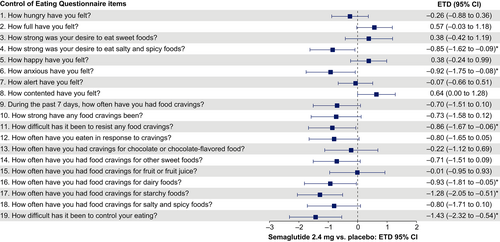

Change from baseline to week 104 for the 19 individual CoEQ scores

From baseline to week 104, individual item scores for desire to eat salty and spicy food, craving for dairy food, craving for starchy food, difficulty in resisting cravings, difficulty in control of eating, and feelings of anxiety were significantly reduced with semaglutide versus placebo (all p < 0.05). Scores appeared to be favorable with semaglutide versus placebo for most other items, including feeling fuller and more content, fewer and weaker food cravings, and reduced frequency of eating in response to cravings, but these comparisons did not reach statistical significance (Figure 4).

Change from baseline to week 20, week 52, and week 104 for selected individual items

Scores for hunger and fullness improved with semaglutide versus placebo at weeks 20, 52, and 104, but the differences between treatment groups were only significant at week 20 (p < 0.001 for both) (Figure 5A). Participant scores for difficulty in resisting cravings and difficulty in control of eating were significantly improved with semaglutide versus placebo from baseline to weeks 20, 52, and 104 (p < 0.05 for both items at each time point) (Figure 5A). For the observed change over time in hunger, fullness, and difficulty resisting cravings, positive responses with semaglutide were observed early and then reached an equilibrium with placebo at the end of the study (Figure 5B–D). For difficulty in control of eating, positive responses with semaglutide were observed early and remained improved compared with placebo to week 104 (Figure 5E).

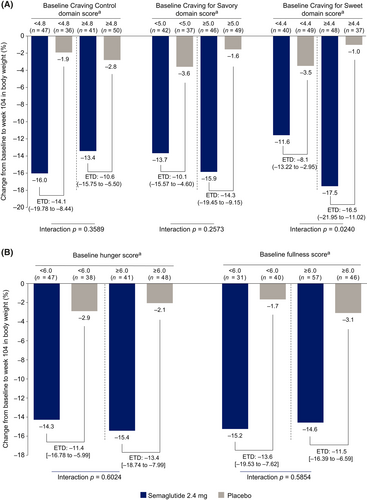

Weight loss by baseline CoEQ craving domain scores (post hoc analysis)

In a post hoc analysis, reductions in body weight from baseline to week 104 in the semaglutide treatment group were numerically greater among participants with lower baseline Craving Control domain scores (i.e., less ability to control cravings) and among participants with higher baseline Craving for Savory and Craving for Sweet domain scores (i.e., more cravings). In the placebo group, the opposite was seen for all three domains. The subgroup interaction was not significant for the Craving Control and Craving for Savory domain scores but was significant for Craving for Sweet domain scores (p < 0.05) (Figure 6A).

Weight loss by baseline hunger and fullness scores (post hoc analysis)

A post hoc analysis to assess whether baseline hunger and fullness scores influenced the amount of weight loss showed that, in the semaglutide group, reductions from baseline to week 104 in body weight were slightly greater (~1.0 percentage point) among participants who had more hunger (higher score) and less fullness (lower score) at baseline. In the placebo group, the opposite was seen. The subgroup interaction was not significant for either of the scores (p > 0.05) (Figure 6B).

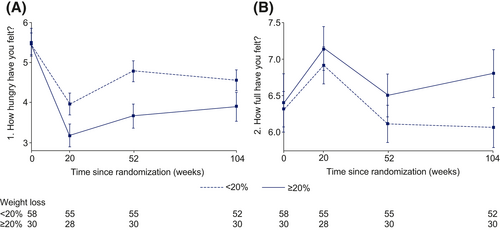

Hunger and fullness over time in people losing <20% body weight and those losing ≥20% body weight

For participants in the semaglutide treatment arm, those with ≥20% reduction in body weight felt less hungry and felt fuller at weeks 20, 52, and 104 compared with those with <20% reduction in body weight (Figure 7). At week 104 in the semaglutide treatment group, participants with a ≥20% reduction in body weight had a mean hunger score of 3.9 whereas those with <20% body weight reduction had a mean hunger score of 4.6. Mean scores for fullness were 6.8 for those with a ≥20% reduction in body weight and 6.1 for those with <20% body weight loss.

Weight loss by baseline CoEQ scores (post hoc cluster analysis)

The cubic clustering criterion was negative for all number of clusters, suggesting a lack of evidence for clearly defined clusters. It was, however, decided to split the data into two clusters, because this resulted in the best separation of the data. Furthermore, evaluation of the mean scores at baseline for each item in the CoEQ revealed that the two clusters differed with regard to cravings and ability to resist cravings. Participants in cluster 1 (n = 104) showed high levels of food craving and a lower ability to resist cravings; those in cluster 2 (n = 45) had lower levels of food craving and a greater ability to resist cravings (Supporting Information Figure S1A). In both clusters, semaglutide was associated with greater percentage weight loss from baseline to week 104 compared with placebo. Weight loss with semaglutide was greater among participants in cluster 1 (−17.3%; 95% CI: −20.2% to −14.3%) than among those in cluster 2 (−9.0%; −13.5% to −4.5%), whereas the opposite pattern was seen with placebo (cluster 1: −1.9%; −5.3% to 1.5%; cluster 2: −4.8%; −9.8% to 0.1%) (Supporting Information Figure S1B).

DISCUSSION

The study's principal finding was that participants treated with semaglutide reported significantly greater improvements in Craving Control and Craving for Savory foods than participants treated with placebo, and these improvements persisted through week 104. However, other domain and item scores in the questionnaire differed between early and later time points in the study. At the earlier time points, only the Positive Mood and Craving for Sweet domains (weeks 20 and 52) and items of hunger and fullness (week 20) were improved with semaglutide versus placebo. At the later time point of 104 weeks, other scores emerged as statistically significant in favor of the semaglutide group compared with placebo in the Craving Control domain and individual items, including desire to eat salty and spicy foods and cravings for dairy and starchy foods, whereas difficulty in resisting cravings and difficulty in control of eating remained significantly improved. Our results suggest that different aspects of control of eating were operative during initial weight loss (early time points) and weight loss maintenance (later time point) with semaglutide treatment, and that an overall reduction in food cravings and craving for savory food was in effect throughout. These effects on control of eating were associated with ~15% weight loss and the maintenance of that weight loss up to 104 weeks. Furthermore, post hoc analyses showed positive correlations between weight loss and changes in craving domain scores. In the post hoc evaluation of weight loss by baseline CoEQ scores, semaglutide was associated with greater percentage weight loss from baseline to week 104 in cluster 1 (−17.3%) than cluster 2 (−9.0%). In contrast, the opposite effect was seen between the two clusters with placebo. These results suggest that improvements in craving domains are associated with greater weight loss, and high food cravings and less ability to resist food cravings could be important moderators of the weight loss effect with semaglutide treatment.

Similar effects on control of eating were observed by Blundell et al. [(6)], who investigated the mechanism of action of once-weekly semaglutide 1.0 mg for body weight loss over 12 weeks in participants with obesity in a randomized, double-blind, two-period crossover study. While this study was shorter and used a lower dose of semaglutide compared with the current study, the greater reduction in body weight with semaglutide (−5 kg) versus placebo (+1 kg weight gain) was associated with greater improvements in appetite and food cravings.

Friedrichsen et al. [(7)] studied the effects of once-weekly semaglutide 2.4 mg on appetite and energy intake in 72 participants with obesity in a double-blind, placebo-controlled study lasting 20 weeks. Again, participants receiving semaglutide lost more weight (10.4 kg) versus placebo (0.4 kg), and the CoEQ results indicated an overall better control of eating, fewer food cravings, and less hunger associated with a reduction in energy intake with semaglutide versus placebo. Similar improvements were observed in our analysis for the CoEQ item scores at week 20 for hunger, cravings, and difficulty in control of eating. While hunger increased and fullness declined after week 20 in semaglutide-treated participants in the present study, these values remained below baseline levels at week 104, an important finding in view of the 14.8% reduction in baseline body weight participants achieved and maintained at this time. These short- and longer-term changes in assessments of hunger and fullness are similar to those obtained in a 52-week open-label trial of the glucagon-like peptide-1 receptor agonist liraglutide 3.0 mg that led to a 12.1% reduction in body weight [(13)].

The combination medication naltrexone/bupropion has also demonstrated improvements in food craving in people with obesity [(14)]. By week 8 of the COR-I trial, greater improvements were seen with naltrexone/bupropion versus placebo in CoEQ items indicating reduced hunger or desire for sweet, non-sweet, or starchy foods; increased feeling of fullness; reduced incidence and strength of food cravings; reduced eating in response to food cravings; and increased ability to resist food cravings and control of eating (all p < 0.05) [(14)].

In the present study, reported improvements in hunger and fullness in semaglutide-treated participants appeared to wane at weeks 52 and 104, and differences between groups were not statistically significant at these times. Metabolic adaptation could explain why there were no significant between-group differences in some appetite measures at follow-up [(3)]. Sumithran et al. prescribed a very-low-energy diet (without adjunctive pharmacotherapy), which induced a mean loss of 14.0% of baseline weight after 10 weeks in participants with overweight/obesity [(3)]. This reduction in body weight was associated with marked increases in ghrelin and reductions in leptin (and other appetite-related hormones), as well as significant increases from baseline in reported hunger and desire to eat. Substantial and maintained weight loss could therefore be expected to be associated with increased hunger and decreased fullness relative to baseline, as reported by Sumithran et al. [(3)], but this was not observed in participants receiving semaglutide in the STEP 5 CoEQ population and could reflect the impact of the pharmacotherapy. That semaglutide enables participants to lose ~15% of baseline weight (while maintaining favorable appetite control) compared with the 6% to 10% produced by most intensive lifestyle interventions, which is often followed by weight regain after 1 year [(15)], suggests that the medication may partially counteract the metabolic adaptation that occurs in response to weight loss with diet and physical activity alone.

A preclinical trial has provided insights into how semaglutide exerts its effects on control of eating and weight loss and found that semaglutide modulated food preference, reduced food intake, and caused weight loss without decreasing energy expenditure in rodents [(5)]. This study showed that following acute semaglutide injection, a marker for neuronal activity called c-Fos was activated in 10 brain areas including those with glucagon-like peptide-1 receptors, such as the hypothalamus and hindbrain, and in areas without glucagon-like peptide-1 receptors, such as the central nucleus of the amygdala and parabrachial nucleus. This is indicative of primary and secondary activation by semaglutide. These brain areas correspond to regions that contribute to appetite regulation related to meal termination [(5)]. It is thus highly likely that the effects that we observed on control of eating are due to modulation of human brain regions involved in regulating eating behavior.

Food cravings are associated with loss of control overeating, which can contribute to development or worsening of obesity and may hinder attempts to lose weight [(16)]. As such, gaining control over food craving is key to the management of obesity [(16)]. In individuals with overweight/obesity and an impaired glucose tolerance, it has been reported that greater food cravings at baseline are associated with a higher BMI, greater weight cycling, more frequent attempts to lose weight, and increased feelings of perceived deprivation while dieting [(16-18)]. Dalton et al. [(16)] assessed whether early changes in craving control (measured using the Craving Control subscale on the CoEQ) were associated with weight loss in four phase 3 clinical trials that investigated sustained-release naltrexone/bupropion in adults with obesity. Participants' body weight was measured at baseline and at weeks 8, 16, 28, and 56. Larger improvements in Craving Control at week 8 were associated with increased weight loss at week 56, illustrating the importance of the experience of food cravings in the management of obesity.

Our analyses of weight loss by baseline craving domain scores demonstrated greater weight loss with semaglutide 2.4 mg in participants who, at baseline, had worse Craving Control, greater Craving for Savory, and greater Craving for Sweet. Similarly, a cluster analysis indicated that, whereas participants with either high or low levels of cravings at baseline both lost considerably more weight with semaglutide than with placebo, the participants who benefited the most from semaglutide were those who had high levels of cravings and who found their cravings hard to resist. This is consistent with other evidence suggesting that semaglutide aids weight loss by reducing hunger and, more specifically, by helping participants to resist food cravings [(6, 7)]. The opposite was seen in the placebo group, where lifestyle intervention was more effective in reducing body weight for those with fewer food cravings than those with greater food cravings. Although the cluster analysis was specified post hoc in STEP 5, such analyses can often assist with recognizing patterns that may be of interest to clarify with future research. While this hypothesis requires further testing with larger sample sizes, the data imply that semaglutide may be particularly effective in enabling patients with challenging food cravings to lose weight and maintain weight loss.

Limitations of this report include the potential for false-positive findings, given the large number of multiple comparisons conducted [(19)]. In addition, the present results are from a subgroup analysis and their generalizability to the larger trial sample is unknown. Finally, the differential effects in subgroups, including those found by cluster analysis, require further study to be confirmed. Nonetheless, the present study provides the largest sample of participants assessed for control of eating with semaglutide treatment to date.

The main strength of this analysis is the trial duration; it is the longest longitudinal assessment of the effect of semaglutide on control of eating. There was also a high retention rate of participants in the active treatment arm at week 104.

CONCLUSION

Semaglutide improves short- and longer-term control of eating, with participants reporting fewer cravings, reduced hunger, and increased feelings of fullness. In addition, semaglutide prevents the compensatory increases in appetite that would otherwise be expected after substantial weight loss. Together, these changes most likely underlie the marked and sustained weight loss effects seen with once-weekly semaglutide 2.4 mg.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

All authors had full access to study data, participated in the manuscript drafting (assisted by a sponsor-funded medical writer), approved its submission, and vouch for data accuracy and fidelity to the protocol.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The authors thank all participants, investigators, and trial staff who were involved in the conduct of the trial. The authors also thank Debbie Day, BSc, of Axis, a division of Spirit Medical Communications Group Limited, for assistance with medical writing and editorial support (funded by the sponsor).

CONFLICT OF INTEREST

Sean Wharton: research funding, advisory/consulting fees, and/or other support from AstraZeneca, Bausch Health Inc., Boehringer Ingelheim, CIHR, Eli Lilly, Janssen, and Novo Nordisk. Rachel L. Batterham: research grant support from Novo Nordisk; consultancy with Boehringer Ingelheim, Eli Lilly, Gila Therapeutics Inc., GSK, Novo Nordisk, Pfizer, and Rhythm Pharmaceuticals. Meena Bhatta: employee of Novo Nordisk A/S. Silvio Buscemi: served as site principal investigator for the clinical trial (he received no financial compensation, nor was there a financial relationship); advisory/consulting fees and/or other support from Boehringer Ingelheim, Eli Lilly, Guidotti Laboratories, Menarini Diagnostics, Novo Nordisk, and Therascience Lignaform. Louise N. Christensen: employee of Novo Nordisk A/S. Juan P. Frias: research support grants from Novo Nordisk; grants and personal fees from Boehringer Ingelheim, Eli Lilly, Merck, Novo Nordisk, and Sanofi; and grants from Janssen and Pfizer. Esteban Jódar: grants from Amgen, AstraZeneca, Boehringer Ingelheim, Eli Lilly, FAES, Janssen, MSD, Novo Nordisk, Pfizer, Sanofi, Shire, and UCB; personal fees from Amgen, AstraZeneca, Eli Lilly, FAES, Helios-Fresenius, Italfármaco, MSD, Mundipharma, Novo Nordisk, UCB, and Viatris. Kristian Kandler: employee of Novo Nordisk A/S. Georgia Rigas: personal (advisory/consultancy and lecture) fees and non-financial support from Gila Therapeutics Inc., iNova Pharmaceuticals, Eli Lilly, and Novo Nordisk. Thomas A. Wadden: serves on advisory boards for Novo Nordisk and WW (formerly Weight Watchers); grant support, on behalf of the University of Pennsylvania, from Epitomee Medical Ltd. and Novo Nordisk. W. Timothy Garvey: grants from Novo Nordisk; serving as site principal investigator for the clinical trial, which was sponsored by his university during the conduct of the study; grants from Eli Lilly, Lexicon, and Pfizer outside the submitted work. He also served as a volunteer consultant on advisory committees for Boehringer Ingelheim, Eli Lilly, Jazz Pharmaceuticals, Novo Nordisk, and Pfizer. In each instance, he received no financial compensation, nor was there a financial relationship. Dr. Garvey has also participated on advisory boards for Fractyl Health and Alnylam Pharmaceuticals and has been compensated for this service.

CLINICAL TRIAL REGISTRATION

ClinicalTrials.gov identifier NCT03693430.

Open Research

DATA AVAILABILITY STATEMENT

Data will be shared with bona fide researchers who submit a research proposal approved by the independent review board. Individual participant data will be shared in data sets in a de-identified and anonymized format. Data will be made available after research completion and approval of the product and product use in the European Union and the United States. Information about data access request proposals can be found at novonordisk-trials.com