Association Between Life-Course Obesity and Frailty in Older Adults: Findings in the GAZEL Cohort

Abstract

Objective

This study aimed to assess the relationship between weight history during adulthood and frailty in late life in men and women participating in the GAZEL (GAZ and ELectricité) cohort.

Methods

This cohort study included 8,751 men and 3,033 women (aged 61 to 76 years) followed up since 1989. Modified Fried’s frailty criteria (weakness, fatigue, unintentional weight loss, low physical activity, and impaired mobility) were assessed in 2015. Reported BMI was determined each year to characterize: obesity status in 2015, obesity duration over the 1990 to 2015 period, and trajectories of BMI. Associations between frailty and weight history were assessed using multinomial regression.

Results

In 2015, 12% of men had obesity, 1.8% severe obesity, and 0.4% morbid obesity; for women, these percentages were 11%, 2.2%, and 0.8%, respectively. Individuals with obesity were more likely to be frail than those with normal BMI and the risk of frailty increased with each additional year of obesity (adjusted odds ratio 1.04 [1.00–1.08] for men and 1.07 [1.02–1.13] for women). Trajectories of BMI revealed that both long-term obesity and onset of obesity in late adulthood were associated with frailty.

Conclusions

Current and past obesity appear to be important determinants of frailty. Early weight management may be beneficial in old age.

Study Importance

What is already known?

- Frailty is a predictor of poor health outcomes among older adults.

- Although weight loss is part of frailty, previous studies demonstrated that aged individuals with obesity are more likely to be frail compared with aged individuals without obesity.

- The impact of life-course obesity on the risk of frailty in old age remains poorly described.

What does this study add?

- In a cohort of older adults followed for 26 years, we showed that the duration of obesity influences the risk of frailty: the longer the period of obesity, the higher the risk of frailty.

- We also identified a persisting effect of obesity on the risk of frailty among individuals who previously had obesity.

Introduction

Frailty is an indicator of decreased physiologic resources and resistance to stressors (1). It can be used to identify a category of older individuals who are no longer robust (nonfrail) but not disabled and who are likely to experience poor health outcomes (2-5). Because weight loss forms part of several definitions of frailty (6), frailty is often associated with underweight. However, overweight and obesity have been found to be associated with frailty (7), challenging the idea that overweight or obesity could represent a protective physiologic reserve. Furthermore, obesity has been suggested as a risk factor for frailty among the elderly (8, 9).

Obesity has reached epidemic proportions in industrialized countries, and it may increase the medical burden of aging populations in a very near future. Indeed, obesity has been associated with numerous comorbidities, such as type 2 diabetes, cardiovascular disease (10), osteoarthritis (11), and cancer (12). Obesity also contributes to low-grade chronic inflammation (9) and tissue remodeling (13). Because the adverse effects of obesity may vary depending on the period and time of exposure, understanding the relationship between obesity and frailty requires a life-course approach.

Stenholm et al. (14) actually showed that midlife history of excess weight was predictive of frailty 22 years later. Among men, Strandberg et al. (15) highlighted that weight gain during adulthood was associated with an increased risk of frailty in old age. Using a 10-year follow-up of weight, Mezuk et al. (16) identified four trajectories of weight evolution among men included in the Health and Retirement Study. The results indicated that, compared with the reference trajectory (consistently overweight), all other trajectories were associated with an increased risk of frailty, especially in the case of weight gain. Recently, Haapanen et al. (17) determined that greater BMI gain in early childhood was associated with an increased risk of frailty in late life among the men of the Helsinki Birth Cohort Study (17).

However, gaps remain in our understanding of the association between frailty in late life and body mass evolution through life, firstly because the description of long-term processes requires repeated measurements over decades, rarely available in epidemiological studies. Secondly, sex differences remain poorly explored in previous studies. Yet men and women exhibit sex differences in obesity, which have been attributed to the differential influences of sex hormones on lipid metabolism and fat distribution (18). These differences in exposure could lead to sex-specific associations and require that analyses be performed among men and women separately.

In a cohort of 11,784 individuals followed up annually for 26 years, we aimed to assess the relationship between weight history during adulthood and frailty in late life in men and women separately. Three different approaches were used: the first assessed the cumulative effect of excess body fat using obesity duration, the second approach assessed the persisting effect of obesity among people with a past history of obesity, and the last approach categorized individuals according to their trajectories of BMI over adult life.

Methods

Population

Our study is part of the GAZEL (GAZ and ELectricité) Cohort Study. Details of the study design have been described elsewhere (19). Briefly, in 1989, 20,625 employees (5,614 women and 15,011 men aged 35-50 years) of the French national electricity and gas utility (Electricité de France-Gaz de France [EDF-GDF]) agreed to participate. Every year, participants were invited to complete a postal questionnaire including a large set of items dealing with health status, lifestyle, and socioeconomic and occupational factors. Data were also collected from national registers and from the personnel and medical departments at EDF-GDF. From the 20,625 participants at inception in 1989, 2,270 (11%) died before 2015, and 493 (2.4%) asked to stop their participation. In 2015, 13,203 (74%) questionnaires were returned. Individuals with missing frailty status (n = 858; 6.5%) and missing BMI in 2015 (n = 496; 3.8%) were excluded from the analyses. Underweight individuals were excluded from the analyses because of their small number in 2015 (n = 125). The final sample was composed of 11,784 (89%) individuals, including 8,751 (74%) men and 3,033 (26%) women, aged between 61 and 76 years old at that time.

Frailty

Frailty was assessed in 2015 according to the five dimensions described by Fried et al. (20). We modified the original criteria, except for weight loss and exhaustion, so that they could be collected by questionnaire, as previously done in other epidemiological settings (15). Weight loss was defined as self-reported unintentional weight loss of ≥ 4.5 kg or a loss of > 5% of current weight during the past 12 months. Exhaustion was assessed using two questions from the Center for Epidemiologic Studies Depression Scale (“I felt that everything I did was an effort”; “I could not get going”) (21). Weakness was defined as self-reported difficulty carrying or lifting a grocery bag and/or difficulty kneeling and standing up. Mobility impairment was defined as self-reported difficulty walking 500 m and/or difficulty climbing stairs without help. Physical activity over a usual week was self-reported. Individuals were considered as having a low level of physical activity if they did not meet at least one of the following requirements: (1) walk for 10 minutes or more at least 5 days a week and (2) practice 10 minutes or more of relatively intense activity (cycling or sport) at least once a week. Frail individuals met three or more criteria, prefrail met one or two, and nonfrail met zero. In cases of missing data regarding frailty criteria, individuals could still be included in the analysis if available information enabled them to be classified as prefrail (presence of one frailty criterion and no more than one missing criterion) or frail (presence of at least three frailty criteria). Otherwise, participants with missing data for whom status could not be determined with certainty were excluded.

BMI

BMI was assessed each year between 1990 and 2015, using self-reported weight (in kilograms) divided by self-reported height (in meters squared). BMI categories were as follows: < 18.5 kg/m2, ≥ 18.5 and < 25 kg/m2, ≥ 25 and < 30 kg/m2, and ≥ 30 kg/m2.

Other variables

Sociodemographic characteristics were sex, age, education (university, high school, or lower than high school), and marital situation (single or in a couple). Age and marital situation were updated in 2015.

Based on annual questionnaires from inception of the cohort to 2015, we defined categories of tobacco consumption (nonsmoker, current smoker, or former smoker) and alcohol consumption (nondrinker or light drinker throughout the follow-up period, current moderate or heavy drinker, or former moderate or heavy drinker [according to self-reported consumption of alcohol during the past week]) (22).

Health problems assessed were cancer, cardiovascular disease, joint pain, psychological problems (depression, stress, or anxiety), and diabetes. Cancer and cardiovascular disease were assessed using validated registers (23, 24) implemented by EDF-GDF from the beginning of the employment period and maintained after retirement. Joint pain, diabetes, and psychological problems were assessed using self-reported information in the 2013, 2014, and 2015 questionnaires (at least one occurrence over the 3 years).

Statistical analysis

Population characteristics are described by numbers and percentages for categorical variables and by means (SD) and ranges for continuous variables.

Obesity duration was defined as the number of years in which reported information indicated BMI ≥ 30 kg/m2. Missing data about BMI during follow-up concerned 6,524 (55%) individuals and were imputed using the “copy mean” method (25) (linear interpolation corrected for the average difference between prediction and observation in the study population) and the “global slope” method (linear extrapolation of the function defined by the first and last values) for intermittent and monotone missing values, respectively (further details about imputation methods in online Supporting Information A).

BMI trajectories were defined using latent class mixed modeling (LCMM) in men and women separately. These models form part of growth mixture modeling, which enables different trends in longitudinal parameter changes in a population to be identified. LCMM was used to describe linear changes in BMI according to age and period of birth (before or after the end of World War II). Indeed, a previous study on the GAZEL cohort highlighted a cohort effect on weight (26), which was confirmed by exploratory data analysis. Models defining one to five latent trajectories were compared using the Bayesian information criterion and the interpretability criterion derived from Nagin’s criterion (27) (see online Supporting Information B for details about models, parameters, and selection).

Because diseases such as cancer and cardiovascular disease may influence weight trajectories, we conducted a sensitivity analysis with the exclusion of participants suffering from these conditions.

The associations between frailty and weight parameters were analyzed in four different models assessing (1) the cross-sectional association between frailty and BMI categories in 2015, (2) the association between frailty and obesity duration (continuous) among individuals with obesity in 2015, (3) the association between frailty and former obesity (binary) among individuals without obesity in 2015, and (4) the association between frailty and BMI trajectories. All the analyses used multinomial logistic regressions. Confounders introduced in models were chosen a priori, in line with the literature. Analyses were conducted separately in men and women. P < 0.05 was considered statistically significant. Results are expressed in terms of odds ratios or adjusted odds ratios (aOR), with 95% confidence intervals.

R statistical software (version 3.4.4) was used, the “longitudinalData” package (version 2.4.1) for imputation, the “LCMM” package (version 1.7.9) for LCMM, and the “VGAM” (Vector Generalized Linear and Additive Models) package (version 1.0-5) for multinomial regression.

Results

Population

The study sample was mainly composed of men (74%) (Table 1). Mean age was 70.5 (SD 2.9) years and 67.8 (SD 4.2) years for men and women, respectively. Mean BMI in 2015 was 26.5 (SD 3.5) among men and 25.4 (SD 4.3) among women. Prevalence of overweight was 50% among men and 32% among women; prevalence of obesity was 15% and 14%, respectively. Women were more often frail (10%) or prefrail (38%) compared with men (4% and 33%, respectively).

| Men (n = 8,751) | Women (n = 3,033) | |

|---|---|---|

| Age (y), mean ± SD | 70.5 ± 2.9 | 67.8 ± 4.2 |

| Age category (y) | ||

| <65 | 0 (0) | 801 (26) |

| 65-74 | 7,668 (88) | 1,997 (66) |

| ≥75 | 1,083 (12) | 235 (8) |

| Marital status | ||

| Living alone | 1,050 (12) | 1,017 (34) |

| Education | ||

| < High school | 1,530 (18) | 761 (26) |

| High school | 5,058 (59) | 1,790 (60) |

| University | 2,027 (24) | 414 (14) |

| Alcohol consumption | ||

| Never more than light drinker | 2,395 (27) | 1,158 (39) |

| Current moderate or heavy drinker | 2,886 (33) | 746 (25) |

| Former moderate or heavy drinker | 3,430 (39) | 1,095 (37) |

| Tobacco consumption | ||

| Nonsmoker | 2,753 (36) | 1,654 (67) |

| Current smoker | 537 (7) | 186 (7) |

| Former smoker | 4,267 (56) | 642 (26) |

| Psychological difficulties | ||

| Depressed, anxious, or stressed | 1,290 (15) | 985 (32) |

| Chronic diseases | ||

| Cardiovascular disease | 826 (9) | 27 (1) |

| Diabetes | 1,113 (13) | 209 (7) |

| Joint pain | 3,400 (39) | 1,671 (55) |

| Cancer | 1,165 (13) | 365 (12) |

| Frailty status | ||

| Nonfrail | 5,448 (62) | 1,602 (53) |

| Prefrail | 2,924 (33) | 1,139 (38) |

| Frail | 379 (4) | 292 (10) |

| BMI (kg/m2), mean ± SD | 26.5 ± 3.5 | 25.4 ± 4.3 |

| BMI category | ||

| Normal | 3,106 (35) | 1,630 (54) |

| Overweight | 4,371 (50) | 975 (32) |

| Obese | 1,274 (15) | 428 (14) |

| Obesity duration among participants with obesity (y), mean ± SD | 15.6 ± 7.3 | 14.8 ± 7.3 |

| BMI trajectory | ||

| Consistently normal or overweight BMI | 8,278 (95) | 2,736 (90) |

| Increasing BMI | 342 (4) | 143 (5) |

| Consistently high BMI | 131 (1) | 154 (5) |

- Figures are expressed as N (%) unless another unit is specified.

Obesity duration

Obesity duration was determined for 11,117 participants (94%). Among individuals with obesity in 2015, mean obesity duration was 15.6 ± 7.3 years for men and 14.8 ± 7.3 years for women, and 76% of men and 73% of women had had obesity for 10 years or more. Those formerly with obesity accounted for 11% of the men and 7% of the women and were mostly individuals with overweight in 2015 (96%). Among individuals formerly with obesity, mean obesity duration was 6.6 ± 5.8 for men and 5.6 ± 5.4 for women with overweight. Mean obesity duration increased with frailty status among participants with overweight or obesity, whether men or women.

Weight trajectories

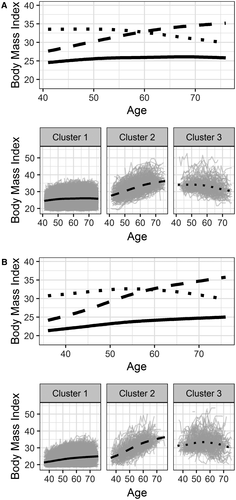

Weight trajectories were determined for the whole study sample (n = 11,784). For both men and women, three clusters of BMI trajectories emerged from the data (Table 2). Figure 1 shows the weight trajectories for men and women.

| Number of latent classes | Log likelihood | BIC | %class1 | %class2 | %class3 | %class4 | %class5 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Model selection among men | |||||||

| 1 | −406,168.4 | 812,403.7 | 100 | ||||

| 2 | −323,234.4 | 646,560.7 | 96 | 4.4 | |||

| 3 | −322 936.8 | 645,992.9 | 95 | 3.9 | 1.5 | ||

| 4 a, b | / | / | / | / | / | / | / |

| 5 a, c | / | / | / | / | / | / | / |

| Model selection among women | |||||||

| 1 | −168,835.1 | 337,730.2 | 100 | ||||

| 2 | −134,891.2 | 268,864.1 | 94 | 5.6 | |||

| 3 | −134,773.9 | 269,653.9 | 90 | 4.7 | 5.1 | ||

| 4 | −134,674.6 | 269,479.7 | 0.5 | 87 | 7.9 | 4.2 | |

| 5 a, d | / | / | / | / | / | / | / |

- a No convergence with initial parameters.

- b Convergence to local solution (two-cluster solution).

- c No convergence with doubled convergence parameters.

- d Convergence to local solution (three-cluster solution).

- %class, prevalence of class 1 to 5 (%); BIC, Bayesian information criterion.

- Cluster 1 comprised 95% of men and 90% of women, with high mean posterior probabilities (> 95%). This group is characterized by a consistently overweight BMI for men and a consistently normal BMI for women. Mean BMI value was 25 for men and 23 for women at age 45 and 26 for men and 25 for women at age 70. Cluster 1 is referred to as “consistently normal or overweight” (reference group).

- Cluster 2 comprised 3.9% of men and 4.7% of women, with mean posterior probabilities greater than 80%. Cluster 2 was characterized by an evolution from overweight to obesity. Mean BMI was 29 for men and 27 for women at age 45, increasing to 35 at age 70 for men and women. Cluster 2 is referred to as “increasing BMI.”

- Cluster 3 comprised 1.5% of men and 5.1% of women, with correct mean posterior probabilities. Cluster 3 was characterized by consistent obesity: mean value of BMI was 34 for men and 32 for women at age 45, decreasing slowly to 31 at age 70 for men and women. Cluster 3 is referred to as “consistently high BMI.”

Health differences were observed between clusters. First of all, the prevalence of frailty and prefrailty was higher in clusters 2 and 3 compared with cluster 1 (Table 3). A higher prevalence of diabetes, joint pain, and cardiovascular disease (men only) was also observed among individuals included in clusters 2 and 3. Sociodemographic and lifestyle differences were also observed, with a lower level of education of men in clusters 2 and 3. They were also more likely to be former smokers.

| Men | Women | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cluster 1, consistently overweight | Cluster 2, increasing BMI | Cluster 3, consistently high BMI | Cluster 1, consistently normal BMI | Cluster 2, increasing BMI | Cluster 3, consistently high BMI | |

| 8,278 (95%) | 342 (3.9%) | 131 (1.5%) | 2,736 (90%) | 143 (4.7%) | 154 (5.1%) | |

| Age (y), mean ± SD | 70.6 ± 2.9 | 69.8 ± 2.7 | 71.1 ± 2.8 | 67.8 ± 4.2 | 66.2 ± 3.6 | 68.4 ± 3.9 |

| Age category (y) | ||||||

| <65 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 725 (26) | 50 (35) | 26 (17) |

| 65-74 | 7,243 (87) | 314 (92) | 111 (85) | 1,797 (66) | 88 (62) | 112 (73) |

| ≥75 | 1,035 (13) | 28 (8) | 20 (15) | 214 (8) | 5 (3) | 16 (10) |

| Marital status | ||||||

| Living alone | 969 (12) | 61 (18) | 20 (16) | 900 (33) | 55 (38) | 62 (41) |

| Education | ||||||

| < High school | 1,436 (18) | 69 (20) | 25 (19) | 675 (25) | 41 (29) | 45 (31) |

| High school | 4,755 (58) | 217 (64) | 86 (66) | 1,623 (61) | 81 (58) | 86 (59) |

| University | 1,956 (24) | 51 (15) | 20 (15) | 381 (14) | 18 (13) | 15 (10) |

| BMI (kg/m2), mean ± SD | 26.1 ± 3.0 | 35.3 ± 3.4 | 31.4 ± 4.1 | 24.5 ± 3.3 | 34.3 ± 4.0 | 32.4 ± 5.2 |

| BMI category | ||||||

| Normal | 3,101 (37) | 1 (0) | 4 (3) | 1,621 (59) | 0 | 9 (6) |

| Overweight | 4,324 (52) | 5 (1) | 42 (32) | 930 (34) | 14 (10) | 31 (20) |

| Obese | 853 (10) | 336 (98) | 115 (65) | 185 (7) | 129 (91) | 114 (74) |

| Alcohol consumption | ||||||

| Never more than light drinker | 2,260 (27) | 84 (25) | 51 (39) | 1,017 (38) | 62 (44) | 79 (52) |

| Current moderate or heavy drinker | 2,753 (33) | 107 (31) | 26 (20) | 691 (26) | 29 (20) | 26 (17) |

| Former moderate or heavy drinker | 3,227 (39) | 150 (44) | 53 (41) | 996 (37) | 51 (36) | 48 (31) |

| Tobacco consumption | ||||||

| Nonsmoker | 2,673 (37) | 56 (19) | 24 (21) | 1,500 (67) | 70 (61) | 84 (67) |

| Current smoker | 503 (7) | 26 (9) | 8 (7) | 173 (8) | 7 (6) | 6 (5) |

| Former smoker | 3,975 (56) | 211 (72) | 81 (72) | 569 (25) | 37 (32) | 36 (29) |

| Frailty status | ||||||

| Nonfrail | 5,298 (64) | 102 (30) | 48 (37) | 1,521 (56) | 41 (29) | 40 (26) |

| Prefrail | 2,669 (32) | 188 (55) | 67 (51) | 1,006 (37) | 61 (43) | 72 (47) |

| Frail | 311 (4) | 52 (15) | 16 (12) | 209 (8) | 41 (29) | 42 (27) |

| Psychological difficulties | ||||||

| Depressed, anxious, or stressed | 1,217 (15) | 53 (15) | 20 (15) | 871 (32) | 55 (38) | 59 (38) |

| Chronic diseases | ||||||

| Cardiovascular disease | 752 (9) | 47 (14) | 27 (21) | 22 (1) | 1 (1) | 4 (3) |

| Diabetes | 918 (11) | 125 (37) | 70 (53) | 134 (5) | 26 (18) | 49 (32) |

| Joint pain | 3,179 (38) | 164 (48) | 57 (44) | 1,473 (54) | 99 (69) | 99 (64) |

| Cancer | 1,107 (13) | 41 (12) | 17 (13) | 332 (12) | 18 (13) | 15 (10) |

Sensitivity analysis excluding participants suffering from cancer or cardiovascular disease led to similar clusters of BMI trajectories.

Association between body size and frailty

The cross-sectional association between frailty and obesity showed that individuals with obesity were far more likely to be prefrail or frail compared with the reference category (aOR > 8 among women) (Model 1, Table 4).

| Men | Women | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Prefrailty | Frailty | Prefrailty | Frailty | ||

| Model 1: Among all participants a | |||||

| BMI category in 2015 (reference: normal BMI) | |||||

| Overweight | Unadjusted | 1.41 (1.28-1.57) | 1.18 (0.92-1.52) | 1.54 (1.30-1.82) | 2.20 (1.61-2.99) |

| Adjusted | 1.38 (1.23-1.55) | 1.11 (0.83-1.48) | 1.55 (1.27-1.89) | 1.79 (1.23-2.60) | |

| Obesity | Unadjusted | 3.41 (2.96-3.93) | 4.65 (3.51-6.16) | 2.84 (2.22-3.64) | 9.41 (6.72-13.2) |

| Adjusted | 3.20 (2.72-3.77) | 4.29 (3.07-6.01) | 3.10 (2.32-4.16) | 8.18 (5.36-12.5) | |

| Model 2: Among participants with obesity b | |||||

| Obesity duration (+1 year) | Unadjusted | 1.03 (1.01-1.04) | 1.04 (1.01-1.07) | 1.03 (1.00-1.06) | 1.06 (1.02-1.10) |

| Adjusted | 1.03 (1.01-1.05) | 1.04 (1.00-1.08) | 1.03 (0.99-1.08) | 1.07 (1.02-1.13) | |

| Model 3: Among participants with overweight c | |||||

| Former obesity: yes vs. no (reference) | Unadjusted | 1.58 (1.34-1.87) | 3.08 (2.16-4.39) | 1.34 (0.92-1.97) | 2.98 (1.76-5.03) |

| Adjusted | 1.52 (1.25-1.85) | 3.00 (1.98-4.55) | 1.20 (0.76-1.91) | 2.05 (0.98-4.28) | |

| Model 4: Among all participants d | |||||

| BMI trajectory (reference: cluster 1) | |||||

| Cluster 2: increasing BMI | Unadjusted | 3.66 (2.86-4.68) | 8.69 (6.10-12.4) | 2.25 (1.50-3.37) | 7.28 (4.61-11.5) |

| Adjusted | 3.72 (2.81-4.93) | 8.78 (5.73-13.5) | 2.41 (1.50-3.87) | 8.36 (4.62-15.1) | |

| Cluster 3: consistently high BMI | Unadjusted | 2.77 (1.91-4.03) | 5.68 (3.19-10.11) | 2.72 (1.83-4.04) | 7.64 (4.84-12.1) |

| Adjusted | 2.30 (1.51-3.49) | 3.84 (1.93-7.64) | 3.06 (1.89-4.94) | 7.97 (4.39-14.5) | |

- Results are expressed as unadjusted odds ratio (top line) and adjusted odds ratio (bottom line), with 95% confidence intervals.

- Adjusted models were adjusted for age, education, marital status, tobacco and alcohol consumption, diabetes, joint pain, psychological problems, and cancer and cardiovascular disease events (only for men). Models for women were not adjusted for cardiovascular disease because of insufficient event size.

- a Conducted on 8,751/7,392 men and 3,033/2,411 women in unadjusted/adjusted models, respectively.

- b Conducted on 1,174/960 men and 397/317 women in unadjusted/adjusted models, respectively.

- c Conducted on 4,145/3,513 men and 905/710 women in unadjusted/adjusted models, respectively.

- d Conducted on 8,751/7,392 men and 3,033/2,411 women in unadjusted/adjusted models, respectively.

Among individuals with obesity, each additional year of obesity increased the risk of frailty with an aOR of 1.04 (1.00-1.08) for men and 1.07 (1.02-1.13) for women (Model 2, Table 4). The risk of prefrailty also increased with obesity duration.

The purpose of Model 3 was to assess whether history of obesity is associated with frailty status among participants without obesity in 2015. The analyses were restricted to participants with overweight because of the low number of individuals formerly with obesity among those with normal BMI in 2015. Among men with overweight, those formerly with obesity had increased risk of prefrailty and frailty compared with men with overweight who had never experienced obesity. Similar results were observed among women, although these were borderline significant.

The last model assessed the relationships between frailty and trends in BMI over time. Compared with the reference group, both the “increasing BMI” and the “consistently high BMI” groups were associated with an increased risk of prefrailty and frailty in both men and women. Of note is the fact that, among men, the risk of frailty was higher among men in the “increasing BMI” group compared with the “consistently high BMI” group.

Discussion

Main findings

In a cohort of 11,784 community-dwelling individuals followed up annually for 26 years, we investigated the relationship between weight history during adulthood and frailty later in life. Results suggest that, firstly, for individuals with obesity in 2015, the longer an individual had spent with obesity, the higher the risk of frailty. Secondly, a past history of obesity seemed to increase the risk of frailty among individuals with overweight. Finally, we identified three clusters of BMI trajectories during adulthood. Trajectories that included obesity were associated with an increased risk of frailty among men and women.

Characteristics of the study sample in 2015

In this study, the prevalence of both frailty and prefrailty in men and women is consistent with pooled estimates by Collard et al. (28), according to which 5.2% of men and 9.6% of women are frail, and 37% of men and 39% of women are prefrail.

Prevalence of overweight was 50% for men and 32% for women, and prevalence of obesity was 15% for men and 14% for women, in line with previous studies in France (29). However, because data about height and weight were self-reported, underestimation is expected. Niedhammer et al. (30) actually reported that participants in the GAZEL cohort were likely to underestimate their weight and to overestimate their height, especially if concerned by overweight. Furthermore, misreporting may change with age, which may contribute to smoothing trajectories. Although this adds a source of uncertainty, specificities remain high: few individuals report a higher BMI category than the one they really are in, which reduces the influence of misclassification error.

Strong associations between obesity and frailty in old age have already been reported (31). In our study, associations between obesity and frailty were also high, within the range of other studies defining physical frailty based on reported indicators (14, 15).

Life-course obesity and frailty

Using life-course approaches allowed us to further analyze the relationship between excessive body fat and frailty.

Obesity duration explores the cumulative effect of exposure to excessive body fat (32). It has been associated with the onset of disability (33) and with decline in walking speed (34) and grip strength (35). Our results suggest a cumulative effect of exposure to excessive body fat, which may reflect the progressive tissue remodeling caused by obesity (affecting, notably, the cardiac tissue and joint compartments) (10, 11, 13) and metabolic changes (36). This observation raises additional concerns about the growing epidemic of obesity (37), especially in children. Long-term exposure to excessive body fat may impair the health and functional capacity of aging cohorts of individuals with obesity.

The analysis considering past exposure to obesity informs on the persisting effect of obesity even when individuals have lost weight. Men with overweight and a past history of obesity had an increased risk of prefrailty and frailty compared with men with overweight and no history of obesity. Similar associations were observed among women, although results were borderline significant, probably because of lower sample size.

However, these two approaches have limits: they assess exposure to excessive body fat with little regard to the overall dynamic of weight change over life.

This issue was addressed by identifying trajectories of BMI. Three clusters of trajectories were identified, with similar patterns among men and women. Other attempts to determine weight trajectories over adulthood have produced similar results in the literature. Using data from a 10-year follow-up among 10,872 elderly individuals (mean age 65 years at baseline), Mezuk et al. (16) identified three trajectories of weight comparable to ours, as well as an additional “weight loss” trajectory. Zajacova et al. (38) also observed the same three main trajectories of BMI, among adults aged 51 to 61 at baseline followed up over 16 years.

We observed that trajectories characterized by long-term or emerging obesity were associated with increased risk of frailty for men and women. Among men, those included in the “increasing BMI cluster” were particularly at risk of frailty. Increased risk of frailty in weight-gain groups was also found in other studies (16, 17). Selection bias, where the most robust individuals with obesity still participate in the study in 2015, could contribute to the observed difference in frailty risk between the weight gain group and the consistently high BMI group. However, when trajectories were defined using the whole cohort sample (results not shown), no differences were found in terms of survival (26% vs. 30%, P = 0.43) or nonresponse (37% vs. 30%, P = 0.09) between men identified in the weight-gain group and those with consistently high BMI trajectories. Mechanisms involved in weight gain remain unclear. Our results indicate health and lifestyle differences between clusters that could be further explored in future research. Although these factors might have constituted confounding factors in the relationship between frailty and obesity, the associations remained after adjustment for comorbidity and tobacco and alcohol consumption.

Of note, similar results and conclusions were found using frailty status based on complete cases (data not shown).

Strengths and limitations

The main strength of this study is the assessment of BMI annually for 26 years, in more than 11,000 men and women, although self-reported height and weight was used. Despite the long follow-up, attrition and missing data were limited; on average, participants in this study returned 22 ± 4 questionnaires out of 26. Missing data were imputed without introducing significant bias in BMI: after introducing missing values among complete cases, we imputed them and observed that the mean differences between imputed and observed data did not exceed 0.2 kg/m2 (25).

Various life-course approaches were used and provided complementary information that helped to provide a better understanding of the long-term effects of overweight and obesity. The 26-year follow-up of the GAZEL cohort enabled us to examine current, cumulative, and persistent effects of overweight and obesity on frailty. However, we could not assess the effect of overweight and obesity in childhood and young adulthood in critical period models (39).

Our assessment of frailty is based on the framework proposed by Fried et al. (20) in 2001, which remains the most commonly used framework in the field of frailty research (6). It also appeared the most relevant in relation to issues associated with weight change because of the conceptual assumptions of this model, in which sarcopenia plays a major role. However, we approximated the measure of walking speed and grip strength using self-reported information. It should be noted that recent findings suggest that such information is as reliable in predicting standard outcomes of frailty as physical measurements (40).

Other limitations must be acknowledged. BMI is a crude measure of fat distribution, which changes over time, especially because of the decrease in lean mass with aging (41). As a result, we may have grouped people based on their BMI who had very different body compositions. Furthermore, the models we used may not be suited to identifying weight changes over short intervals.

Conclusion

Our results suggest that current and past obesity plays a decisive role in frailty in late life. Taking into account life-course obesity, notably its duration, may help with stratifying the risk of frailty among aging individuals. From a clinical perspective, frailty assessment should not be neglected among individuals with obesity nor should screening for former obesity. From a prevention perspective, weight control could be beneficial at all ages and reduce the risk of frailty in aging populations.