Patient Transfer Process From Pre-Hospital to the Hospital Emergency Department: A Grounded Theory Study

Funding: The authors received no specific funding for this work.

ABSTRACT

Background

The transfer of patients from a pre-hospital emergency environment to a qualified healthcare centre is a critical aspect of emergency care. Due to the unpredictable and uncontrolled nature of pre-hospital environments, emergency care providers often encounter multiple challenges during the patient transfer process.

Aim/Objective

This study aimed to explore the patient transfer process from pre-hospital to the hospital emergency department, identify the areas of main concern, strategies that emergency care providers used to address these concerns and generate a coherent underlying theory.

Methods

A qualitative research method using a grounded theory approach was carried out to develop a comprehensive theoretical framework based on the experiences of emergency care providers, patients and their relatives in pre-hospital settings and hospital emergency departments. This study, conducted from September 2022 to January 2024, involved 24 participants: 18 emergency care providers, four patients' relatives and two patients with transfer experience. Sampling began purposefully and transitioned to theoretical sampling to ensure diversity and enrich the emerging theory. Data were collected through in-depth, individual, semi-structured interviews, along with note-taking, observation and document review. The Corbin-Strauss 5-step analysis approach was used to develop a coherent theory capturing the essence of the study phenomenon. The steps included open coding to identify concepts, developing concepts based on their features and dimensions, analysing data for context, incorporating processes into the analysis and integrating categories.

Results

The main category as the main concern of the participants was ‘the tension of delay in safe transfer and patient survival threat’. The central variable was ‘diligent avoidance of tense confrontation’, which was used as a conscious, deliberate and purposeful effort to prevent the escalation of tensions in various situations and included a set of different strategies such as situational resourcefulness, persuasive communication and forbearance. Ultimately, the emergency care providers' efforts caused different outcomes, from successful persuasion and safe transfer of the patient to unsuccessful persuasion, surrendering, escaping from responsibility and long-lasting hidden tensions.

Conclusions

Emergency care providers use different strategies to manage the tension of delay in safe transfer and patient survival threat as their main concern. While successful strategies can inform practical guidelines, negative consequences highlight the need for more efficient and effective approaches. A prescriptive model based on the contextual theory from this study can be designed. This model should take a comprehensive, multifaceted view of the underlying causes of tension, support emergency care providers and improve their experience of delays during patient transfers in pre-hospital emergency settings, ultimately leading to safe care.

Implications for the Profession and/or Patient Care

Emergency care providers should balance the urgency of transfer with patient safety and the patient's relative concerns.

Impact

This study underscores the need for patient-centred care, effective communication and practical strategies to improve patient transfer processes.

Reporting Method

This article has been presented based on the COnsolidated Criteria for REporting Qualitative Research (COREQ) checklist.

Patient or Public Contribution

No Patient or Public Contribution.

1 Introduction

The pre-hospital emergency system operates with a defined mission and encompasses a range of actions. It starts at the telephone communication centre where requests for emergency aid are received, followed by the dispatch of an ambulance to the incident site (Kashani et al. 2018). Upon reaching the scene, the emergency personnel assess the patient's condition, prioritise the care needed, deliver necessary assistance and make decisions about hospital transfer (Razzak and Kellermann 2002; van Vught et al. 2019). The immediate patient transfer to the hospital is considered a crucial part of emergency care (Droogh et al. 2015; Vähäkangas et al. 2023). Emergency care providers maintain the continuity of patient care as the main goal of patient transfer (Delbridge et al. 2015; Flink et al. 2018) by effectively communicating clinical information and transferring care responsibility to hospital staff upon arrival (Johnson et al. 2016).

2 Background

Patient transfer has been widely acknowledged as a challenging, risky and logistically problematic process in the international literature (Droogh et al. 2015; Eiding et al. 2019). The challenges encompass a spectrum of factors including the diversity of patients' conditions, the coordination of care between distinct pre-hospital and hospital systems, collaboration among clinical experts from various disciplines, restricted access to comprehensive patient medical records, high personnel workloads, managing a multitude of transitional patients and navigating within constrained timeframes (Dawson et al. 2013; Shook et al. 2016). Moreover, the patient's relatives play a crucial role in the patient transfer process (Primc et al. 2023; Grønlund et al. 2023). They can serve as callers, initiating requests for assistance and directing ambulances to the scene. Additionally, they may administer first aid, offer reassurance to the patient, recount the events leading up to the emergency, provide background information about the patient and act as proxy decision-makers on behalf of the patient (DeJean et al. 2016). Since various individuals involved in patient transfer may interpret emergency events differently (DeJean et al. 2016), the active involvement of the patient's relatives can facilitate optimal patient treatment by emergency care providers (Primc et al. 2023; Grønlund et al. 2023). However, they can cause interruptions in patient care and treatment (Shook et al. 2016) and potentially compel emergency staff to administer unnecessary resuscitation efforts (Grønlund et al. 2023).

Emergency Medical Services (EMS) professionals often receive inadequate training in managing interactions with the family members of patients and balancing their needs. Due to the diversity of cultures and the advancements in medical technology, many EMS professionals find it difficult to interact with family members during emergency situations (Loyacono 2001).

In pre-hospital settings, emergency responders may encounter a wide range of conditions or complaints that necessitate thorough investigations and effective communication. However, communication and information exchange in emergency situations need to be performed quickly due to time constraints (Eadie et al. 2013), which create stressful experiences for most people (Satchell et al. 2023). Such conditions demand personnel to maintain an open and flexible approach, necessitating extensive knowledge and skill sets and special competence to effectively meet patients' needs (Sundström and Dahlberg 2012). Emergency care providers need to possess professional competencies and an understanding of different conditions (Wilson et al. 2015). However, the qualifications of personnel providing emergency services vary from country to country, influenced by cultural, economic, organisational and social factors (Dúason et al. 2021). Consequently, the standards and quality of care exhibit significant variations (Xavier et al. 2008; Lozano et al. 2012).

Emergency care providers, responsible for assessing and treating patients in the prehospital setting, also manage their transfer to hospital emergency departments (Sanjuan-Quiles et al. 2019). They face daily emergencies requiring immediate action and must manage chaotic, high-risk scenarios while maintaining composure (Oliveira et al. 2019). Evidence indicates that in 50% of cases, patients assessed in the prehospital setting have non-urgent conditions that do not require immediate medical intervention (Ek et al. 2013). Operational staff are uniquely positioned to assess the actual need for patient transfers (Mulholland et al. 2005). However, some evidence challenges the accuracy of judgements and decisions made by staff regarding the need for transfer (Mulholland et al. 2005; Brown et al. 2009; Fullerton et al. 2012), as these decisions are often based on mental processes and the emergency context rather than scientific evidence (Fullerton et al. 2012). This discrepancy may stem from the varying levels of knowledge, expertise, clinical judgement and decision-making abilities among pre-hospital emergency service staff (Ebrahimian et al. 2012). Additionally, issues such as conflict, pressure, heavy workload, poor communication, lack of social support, hierarchical communication and limited control over work and organisational decisions contribute to the challenges faced by these workers in the pre-hospital environment (Oliveira et al. 2019). Therefore, it is crucial to understand the primary challenge or concern faced by emergency care providers amid the many challenges they encounter. Key questions include What conditions contribute to this main concern? What strategies do they use to manage it, What are the outcomes? What factors facilitate effective management and what barriers hinder their ability to address the main issue effectively?

Currently, there is a growing interest in pre-hospital emergency research. However, many studies in this field are limited in scope, focusing only on specific issues within pre-hospital emergency care. To align with broader healthcare systems, it is crucial to continually enhance the quality of prehospital emergency services, relying on the best available evidence. Additionally, the process of patient transfer in prehospital emergency care has not been thoroughly evaluated. Therefore, conducting qualitative research using grounded theory methods to explore various facets of the patient transfer process is essential. This approach can offer a more detailed and comprehensive understanding of the challenges and nuances associated with transporting patients during prehospital emergencies.

3 The Study

This study aimed to explore the patient transfer process from pre-hospital to the hospital emergency department, identify the areas of main concern in this process, the strategies that emergency care providers used to address these concerns, the consequences of these strategies and finally develop a coherent underlying theory. Accordingly, the research question was How do emergency care providers manage the patient transfer process from pre-hospital settings to the emergency department?

4 Methods

4.1 Study Design

A qualitative study using a grounded theory approach was conducted. Qualitative research enables the exploration of the natural context and factors influencing the phenomena being studied. Grounded theory examines the nature, structure and process of the research phenomena, providing a comprehensive understanding of the relationships between factors influencing the subject matter (Holloway and Galvin 2023).

The research method was selected based on the study's questions and objectives. To explore the patient transfer process from pre-hospital to hospital emergency departments, a qualitative approach using grounded theory by Corbin and Strauss (2015) was applied.

Strauss and Corbin's grounded theory, influenced by pragmatism and symbolic interactionism, emphasises understanding social processes through the meanings participants attribute to their experiences. They introduced detailed coding procedures to systematically analyse qualitative data, incorporated constructivist elements and recognised the role of researchers' interpretations in shaping the theory. This method was chosen for its structured coding, focus on social processes, adaptability, practical application and capacity for generating rich interpretations (Corbin and Strauss 2015).

4.2 Setting and Samples

This study involved 24 individuals who had experience in transferring patients from pre-hospital emergency settings to hospital emergency departments. This study included individuals with extensive experience in patient transfer during emergencies, who were willing to participate and could effectively communicate their experiences. Participants consisted of prehospital emergency care providers, including nurses, paramedics and dispatchers, as well as hospital emergency care providers, such as nurses and triage nurses. Additionally, patients or their relatives, who requested emergency assistance and were involved in all stages of patient transfer, also participated. Sampling for the study began purposefully, but as conceptual categories emerged, participants were selected theoretically to enhance the depth and richness of the study findings. The study was conducted in various pre-hospital emergency centres located in urban, air and road settings as well as emergency departments of hospitals across seven cities of Iran.

4.3 Data Collection

Data were collected between October 2022 and December 2023. After getting permissions from healthcare authorities, the first author as the main researcher visited a pre-hospital emergency base, a telephone communication centre and a hospital emergency department in each city to invite potential participants for interviews. Data collection continued through individual semi-structured interviews, observation, writing field notes and reviewing documents related to the patient transfer process. Due to the coincidence of the initial stages of data collection with the COVID-19 epidemic, the first interviews were conducted online through Skype, WhatsApp and Google Meet. However, subsequent interviews were conducted face-to-face. To establish trust, the participant's role in the research was explained before each interview session. Data regarding demographics encompassing age, gender, work experience, education level, type of emergency base, place of residence and reason for contacting pre-hospital emergency services were collected and documented for both personnel and patients/relatives.

The interviews began with an open-ended question to help the participants freely share their experiences and were directed towards semi-structured interviews to ask more specialised questions about the study phenomenon. ‘How do you transfer a patient from a pre-hospital emergency setting to a hospital emergency department?’ Based on the participants' answers, further questions were formulated and exploratory questions were asked as follow: ‘Can you explain it to me more’, ‘What do you mean by this statement?’ ‘What happened after that?’ and ‘What was the result?’

In all stages of data interpretation and coding, reflective memos were written to facilitate the formation of categories and the theory. Also, subsequent interviews were organised based on the analysis of data collected from previous interviews to address gaps in the emerging theory such as using theoretical sampling. Key informants were selected to ensure maximum variation in sampling. The researcher continued to deepen their understanding by writing memos and asking more in-depth questions about emerging categories until all their dimensions, characteristics and inter-connections were identified, and theoretical saturation was achieved. Accordingly, after conducting 22 interviews, the researcher found that the newly collected data did not generate new findings. However, two more interviews were conducted to ensure reaching data saturation. The interviews lasted between 30 and 80 min with an average of 55 min. Finally, the researcher synthesised the findings and identified the central theme to craft the narrative of the study, facilitating the potential for theory development.

Engaging in both pre-hospital and hospital emergency settings, the researcher meticulously gathered data through keen observation as a non-participant observer. These observations were meticulously recorded in detailed field notes to facilitate comprehensive data analysis. Additionally, the researcher reviewed various documents including the patient's pre-hospital care electronic form, the hospital triage electronic form, and the patient's admission file in the emergency department. The insights gained from these documents were integrated into the data analysis process, enhancing the depth and richness of the findings.

4.4 Data Analysis

The data were analysed using the constant comparative analysis approach suggested by Corbin and Strauss (2015). It involves several steps, including open coding to identify concepts, elaborating on concepts by examining their characteristics and dimensions, analysing the context, incorporating the process into data analysis and ultimately integrating categories (Corbin and Strauss 2015). Throughout the research process, data collection and analysis occurred concurrently. Each interview session's data were analysed and coded, informing subsequent interviews. This iterative process facilitated the creation and validation of concepts as they emerged.

The interviews were transcribed verbatim and meticulously reviewed multiple times to comprehend the participants' perspectives comprehensively. Meaningful units were identified, and corresponding codes were assigned. Through ongoing comparison of codes, contextual similarities and differences were discerned, leading to the organisation of related codes into categories and sub-categories. These categories were further developed based on their defining characteristics and dimensions. Emerging insights, developed categories and overarching themes were documented to inform theoretical sampling, facilitating the identification of latent patterns and relationships within the data.

Once concepts, sub-concepts and their attributes were identified, the data were restructured by linking categories and sub-categories, thereby revealing main categories and themes encapsulating the core ideas within the data. These categories were synthesised, and their attributes, characteristics and interrelationships were thoroughly explored to construct the main category and a cohesive theory. Any gaps identified in the theory were addressed through theoretical sampling and additional interviews, ensuring a comprehensive understanding of the phenomenon under study.

4.5 Ethical Considerations

The Research Ethics Committee of Tarbiat Modares University approved the study research protocol and corroborated its ethical considerations (approval code: TMU.REC.1401.135). All participants were provided with a comprehensive explanation of the research objectives and methodology. Prior to data collection in both pre-hospital settings and hospital emergency departments, appropriate permissions were obtained. They were assured that their data would be kept confidential, and their personal information would be anonymised. They were also informed of their right to withdraw from the study. Informed consent was obtained from willing participants, and permission for audio-record interviews was also sought. Also, the researcher obtained permission from the officials at both the Medical Emergency Management Centre and the hospital's emergency department that allowed her to be actively present in the authentic field environment, where they could responsibly collect data through direct observation and document review.

4.6 Rigor

The findings were evaluated for accuracy and scientific validity through various methods including triangulation, audit trail, low-interference description, reflexivity, member checking, external checking and long-term involvement. The data were carefully transcribed, ensuring accuracy and fidelity to the original recordings. The researcher had a long-term engagement with the data and the participants. To ensure accuracy, brief reports of interviews and research findings were presented to some participants for member check, and they approved the suggested interpretations. For peer checking, the data analysis process and levels of abstraction underwent external review and approval by three experienced nursing faculty members proficient in qualitative research methodologies. The research team collaborated with the data analysis process to ensure the convergence between the transcriptions, generated codes, concepts and categories. The theoretical sampling with a maximum diversity based on gender, education level, type of education, work experience and workplace improved the depth and variation of the data collection. For the audit trial, the entire process of data collection, coding, analysis and development of main categories was documented. The practical strategies used by the participants to cope with the situation during the patient transfer process from the pre-hospital setting to the emergency department were identified to increase the applicability of the research findings. This article has been reported based on the COnsolidated Criteria for REporting Qualitative Research (COREQ) checklist (Appendix S1) (Tong et al. 2007).

5 Findings

The participants included 13 personnel working in the pre-hospital emergency (10 operational personnel and 3 dispatchers); 5 personnel working in the hospital emergency (3 emergency nurses and 2 triage nurses), 2 patients and 4 patients' relatives. The average working experience of the participating personnel was 9.3 years. The average age of the participants was 28.7 years. Also, 65.4% were men, and 34.6% were women (Table 1).

| Participant | Role | Variable | Characteristics |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1–13 | Pre-hospital personnel | Gender |

Male: 77% Female: 23% |

| Age, year |

Minimum age: 26 Maximum age: 62 Average age: 32 |

||

| Work experience, years |

Minimum work experience: 2 Maximum work experience: 13 Average work experience: 8.6 |

||

| Type of education |

Nursing: 38.4% Emergency technician: 46.4% Anaesthesia: 7.6% Operating room technician: 7.6% |

||

| Level of education |

Associate: 15.4% Bachelor: 69.2% Masters: 15.4% |

||

| 14–18 | Hospital emergency personnel | Gender |

Male: 60% Female: 40% |

| Age, years |

Minimum age: 27 Maximum age: 62 Average age: 40.4 |

||

| Work experience |

Maximum work experience: 4 Minimum work experience: 28 Average work experience: 13.2 |

||

| Discipline |

Nursing: 80% Anaesthesia: 20% |

||

| Level of education | Bachelor: 100% | ||

| 19–24 | Patients and relatives | Gender |

Male: 23% Female: 77% |

| Age, years |

Minimum age: 30 Maximum age: 82 Average age: 52 |

||

| Level of education |

Associate: 33.3% Bachelor: 50.1% Master: 16.6% |

||

| Family relationship of companions with the patient |

Patient: 33.33% Patient's mother: 16.66% Patient's child: 33.33% Patient's wife: 16.66% |

||

| Reason for calling |

Chest pain Severe burn Active bleeding from the nose Poisoning Loss of consciousness |

The data analysis led to the development of six main categories: ‘responsible transfer of the patient’, ‘exposure of personnel to extreme anxiety and violence of the patient's relatives’, ‘judicious control of tension’, ‘compulsory acceptance’, ‘conflict of will-will’ and ‘unsafe emergency services’ (Table 2).

| Concept | Category | Subcategory |

|---|---|---|

|

Responsible patient transfer |

Continuous preparation |

Constant preparation of emergency personnel Checking the supplies and equipment before each mission Immediate response to requests for help Immediate dispatch to the mission site under any condition |

| Operations leading |

Telephone guidance of the mission Asking for help from other organisations Disambiguation of the patient's address Prior coordination for the transfer of critically ill patients |

|

| Continuous monitoring of the patient's condition |

Initial assessment of the patient's condition at the mission site Taking basic history from the patient or family Checking the condition of the patient during transfer Examining the condition of the patient in the triage unit Continuing patient examination in the emergency department Prioritising the level of patient care |

|

| Continuous treatment and care of the transitional patient |

Primary therapeutic and care interventions at the mission site Continuation of medical care measures during the transfer Facilitating and speeding up the treatment of critically ill patients Delivering the patient to the emergency department personnel Continuity of treatment care measures in the healthcare center |

|

| Maintain optimal communication |

Continuous communication with the patient and the patient's companion Keeping the family constantly informed of the patient's condition Verification of patient information through relatives |

|

| Safety considerations |

Complete immobilisation of the patient Compliance with infection control precautions Taking preventive measures to avoid further harm to the patient |

|

| Documentation |

Recording mission information Recording the actions and results of patient assessment Creating a patient record for hospitalisation |

|

| Optimal management of resources |

Maximum use of time in patient transfer Optimal use of available facilities Management of traffic obstacles Using low-experienced personnel under the supervision of senior personnel |

|

| Situational decision making |

Decision-making based on the patient's problem Cautious decision-making Decision-making based on knowledge and experience Conditional presence at the patient's bedside in an unsafe area Decision-making based on legal restrictions |

|

| Negligence of personnel and managers |

Ignoring the checking of ambulance equipment Ambiguous addressing of the mission location by dispatch personnel Negligence in taking actions responsibly Employing low-experienced personnel |

|

| Encountering with extreme concern and violence of the patient's family | Extreme family restlessness |

Expressing the deep concern of the family about the deterioration of the patient's condition The pressure of the companions to hurry up the treatment of the patient The low level of resilience of anxious companions |

| Insufficient trust of the companions in personnel's competence |

Family's lack of confidence in the emergency personnel's performance Family concerns about the personnel negligence |

|

| Companions' ineffectiveness in managing stress |

Inadequate exchange of information due to companion's severe anxiety Disruption in understanding the content of words due to companion's severe stress Disturbance in the patient companion's awareness of the real passage of time Companions' fear of implementing actions according to telephone training |

|

| Violent protest of the companions to the performance of the personnel |

Physical damage to ambulance equipment by the patient's relatives Companions' physical attack on emergency personnel at the scene of the accident The harsh treatment of the companions to get the patient's treatment quickly |

|

| Relatives of the patient complaining about the delay of the ambulance |

Objection for the delay of the ambulance Dissatisfaction with the lack of timely ambulance response |

|

| Aggressive treatment of patients' companions with staff |

Contentious arguments between companions and personnel Expressing extreme dissatisfaction with the delay of the ambulance |

|

| Insulting objection of the companions to the performance of the personnel |

Companions' protest to the emergency personnel using rude words Cursing the staff by the patient's companions |

|

| The threatening protest of the companions to the emergency personnel |

Intimidating emergency personnel by threats to legal action The strong emphasis of the patient's companions on pursuing a legal complaint Death threats to personnel by the patient's companions |

|

| Continuous family presence |

Family cooperation in the initial assessment of the patient and life-giving measures Family cooperation in moving and maintaining the patient's safety Scene management with the help of companions Calming the tense atmosphere through the mediation of a family member Expressing the family's gratitude to the staff |

|

| Judicious control of tension | Tactful tension control |

Reassuring companions to calm the tense atmosphere Clarifying and providing necessary recommendations to companions Focusing on patient care to control stress Giving appropriate feedback to control the tension Giving hope to the patient or the patient's companion to control tension Informing the companions to control the tension Removing the patient from the stressful environment |

| Tolerance |

Tolerating stressful conditions Compromising psychological safety Empathising with the patient and the relative's condition |

|

| Persuading |

Convincing companions Gaining the trust of the patient or the patient's companion Calming companions Controlling the tension of companions by practical actions |

|

| Compulsory acceptance | Forced acceptance |

Withdrawing from their professional decisions Complying with the wishes of the family against their professional opinions |

| Mandatory patient transfer |

Requiring personnel to obey the decisions of superiors Imposing non-emergency transfer of the patient to operational personnel Patient transfer due to power and facility limitations Unavoidable transfer of the patient due to staff's concerns about its consequences |

|

| Conflict of will-will | Contrasting the requests of hospital and pre-hospital personnel |

Expressing displeasure of emergency personnel regarding patient transfer by emergency personnel Disagreement between pre-hospital and hospital emergency personnel regarding patient transfer |

| Disputing the family's wishes and the emergency personnel's decision |

Patient or family resistance to staff decisions Insistence of the family on their wishes against the opinion of the staff |

|

| Unsafe emergency services | Tense work atmosphere |

The high psychological burden of the pre-hospital environment The mental suffering due to repeated exposure to distressing events Stress-causing presence of the patient's companions |

| Defective infrastructure of emergency services |

Depreciation of the transport fleet Insufficient support from officials Disruption in the emergency communication system Inadequate interaction of other agencies with emergency Difficulty accessing a doctor Emergency department overcrowding Public ignorance of pre-hospital emergency |

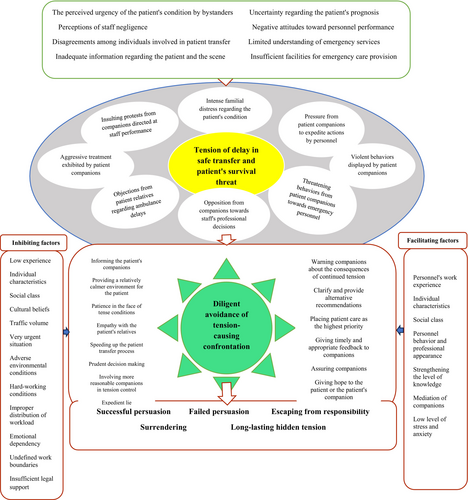

The study found that emergency care providers' main concern was ‘the tension of delay in safe transfer and the threat to patient survival’. Several individual, organisational and social factors contributed to this concern. The central variable, ‘diligent avoidance of tense confrontation’, was identified as a set of strategies, including situational resourcefulness, persuasive communication and forbearance. While this strategy is a conscious effort to manage tension in various situations, its effectiveness can be influenced by several factors. The efforts of emergency care providers resulted in outcomes ranging from successful persuasion and smooth patient transfer to unsuccessful persuasion, avoidance of responsibility, and lasting hidden tension. Ultimately, a theory of diligent avoidance of tension-causing confrontation in the patient transfer process was developed through the integration and refinement of related concepts (Figure 2).

5.1 The Main Concern

Two young men riding a motorcycle hit an old man, the companions were shouting, they wanted to hit the ambulance with sticks, they were shouting: ‘why did you arrive late?’ (Operational personnel, p 1).

Their behavior was inexplicable; they stood chest-to-chest, adopting a confrontational stance, speaking in a bullying tone, visibly agitated, and expressing frustration, and stating: ‘You are coming too late’. (Operational personnel, p 4)

| Category | Subcategory | Sample code |

|---|---|---|

| The tension of delay in safe transfer and patient's survival threat | Intense familial distress regarding the patient's condition |

Extreme restlessness of dispatch callers (participant11, p12 and p13) Hurried and chaotic requests for emergency help by the patient's relatives (p11. p12, p13, p8 and p9) Family's extreme concern about the patient's condition (p2, p3, p4, p8, p22 and p23) Worried and hurried family on the scene (p2, p3, p4, p6, p7, p8, p9 and p10) Continuation of the family member's concern about worsening the patient's condition during the transfer (p1, p2, p22 and p8) Quick searching for the cause of the ambulance stops by the patient's companion (p1, p2 and p22) The patient's anxiety about the possibility of the patient not reaching the hospital on time (p8 and p22) More intense discomforting of critical patient's companions (p6, p14, p16 and p17) |

|

Pressure from patient companions to expedite actions by personnel |

Callers focusing on the immediate dispatching of an ambulance (p2, p8, p11 and p13) Emphasising the quicker dispatch of an ambulance by the anxious callers (p12 and p13) Insisting request of the patient's companions to take urgent actions (p3, p4, p5, p8, p16 and p17) The patient's accompanying request for rapid transfer instead of stopping for resuscitation (p7 and p8) Non-stop follow-up of patient companions to quickly perform procedures (p15, p16, p17, p21 and p22) |

|

| Objections from patient relatives regarding ambulance delays |

Questioning the emergency personnel by the family due to their late arrival (p2, p3 and p12) Complaining about the late arrival of the ambulance by the patient's relatives (p1, p2, p10, p11, p12 and p13) The strong protest of the patient's companions about the late arrival of an ambulance (p2, p4, p8 and p24) |

|

|

Opposition from companions towards staff's professional decisions |

Companions' insisting on transferring the patient to their requested hospital (p2, p4, p7, p8, p10 and p13) Companions' insisting on speeding up the patient transfer instead of performing resuscitation on the scene (p6, p8 and p9) Companions' insisting on accompanying the patient in the ambulance despite the staff's objection (p1, p2, p3, p5, p7, p8 and p10) |

|

| Insulting protests from companions directed at staff performance |

Companions protest to the emergency personnel using rude words (p2, p6, p8, p13 and p14) Cursing the patient's companions to the staff (p4, p9, p12, p13, p14 and p18) The caller's request from dispatch to hurry up to send an ambulance in a disrespectful tone (p2, p8, p11, p12, p13 and p24) |

|

|

Threatening behaviours from patient companions towards emergency personnel |

Threatening emergency personnel to register a complaint by patient's relatives (p2, p3, p8, p10 and p13) Threatening staff to death by patient's relatives (p1, P4, p7, p8 and p13) |

|

|

Aggressive treatment exhibited by patient companions |

Patient companions wrathfully talking to emergency personnel (p1, p2, p4, p7 and p10) Furious request of the patient's companions to speed up the actions (p14, p18 and p22) The anger of the patient's companions due to the chaos of the emergency department (p17 and p22) Companions getting angry due to the feeling of the staff neglecting the patient (p2, p8, p10 and p22) |

|

|

Violent behaviours displayed by patient companions |

The wrathful treatment of the people around the injured person at the scene (p1, p2 and p4) Damage to the ambulance by the patient's companion at the scene (p1 and p6) The patient's companions attacked the pre-hospital emergency personnel in protest of the delay in patient treatment (p1, p2, p4, p7 and p10) Physical attack of the patient's companions on the emergency department personnel (p16 and p18) |

5.2 The Context

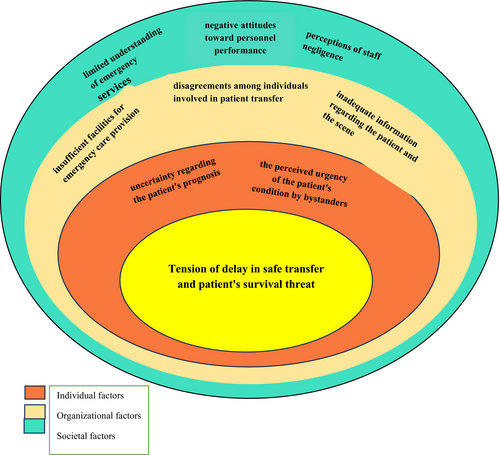

Various factors contributed to ‘the tension of delay in safe transfer and patient survival threat’. They encompassed various elements such as the perceived urgency of the patient's condition by bystanders, uncertainty regarding the patient's prognosis, perceptions of staff negligence, negative attitudes towards personnel performance, disagreements among individuals involved in patient transfer, limited understanding of emergency services, inadequate information regarding the patient and the scene and insufficient facilities for emergency care provision. These factors have been classified into three overarching levels: ‘individual’, ‘organisational’ and ‘societal’ (Figure 1).

I was driving to the hospital with the siren blaring, and the patient's companion was very stressed, very upset, he kept saying: ‘Go quickly, why don't you go faster?’ [loudly], he was talking to me in a very bad tone, from the window of the ambulance, he had turned his head outside, and he was saying to the people: ‘Go away, my patient is very sick and unwell.’ (Operational personnel, p 8)

It took us 7 min from the moment we departed the base until we arrived at our destination. Despite our prompt response, they still claimed that we were arriving late. It's perplexing; I wonder what misconceptions have circulated about the pre-hospital emergency department, consistently leading them to believe that we are tardy. (Operational personnel 9)

5.3 Factors Affecting the Process of Managing the Tension of Delay in Safe Transfer and Patient Survival Threat

Through the analysis of participant experiences, it was discovered that various factors, acting as facilitators or barriers, influenced the adoption of different strategies by personnel in managing the tension surrounding delayed patient transfer and the threat to patient survival, consequently yielding positive or negative effects. Among these factors, key ones included the personnel's level of work experience, behaviour and professional appearance; their knowledge level; the mediation of companions; individual characteristics; stress and anxiety levels; social class; cultural beliefs of companions; traffic volume; environmental conditions; urgency of the patient's condition; working conditions' difficulty; workload distribution; emotional dependence of relatives on the patient; ambiguous work boundaries; insufficient support from authorities and inadequate legal support.

5.4 The Process of Managing the Tension of Delay in Safe Transfer and Patient Survival Threat

Emergency care providers employed a variety of strategies in response to the tension surrounding the delayed patient transfer and the threat to patient survival, as per the participants' experiences: ‘situational resourcefulness’, ‘persuasive communication’ and ‘forbearance’ (Table 4).

| Category | Subcategory | Sample code |

|---|---|---|

|

Situational resourcefulness |

Speeding up the patient transfer process |

Speeding up dispatching an ambulance for a more restless caller (p13) Using a special code to accelerate the transfer of a more critical patient (p2, p4, p5, p6, p7, p8, p9, p11, p12 and p13) Moving the ambulance to the healthcare centre at high speed (p1, p3, p4, p5, p6, p7 and p8) Using the siren to accelerate patient transfer (p4, p7 and p8) Dangerous overtaking of the ambulance driver to accelerate hospital arrival (p7, p8 and p9) |

|

Prudent decision-making |

The caution of dispatch personnel in determining whether the patient is an emergency or non-emergency case (p11, p12 and p13) Transmitting the final decision regarding the transfer of the patient to the operational personnel in case of doubt by the dispatch personnel (p12 and p13) Transferring the patient without vital signs to maintain the safety of personnel (p6, p7 and p9) Transferring the non-emergency patient due to the threat to the personnel by the patient's companions (p6, p7 and p8) Transferring the deceased patient due to the possibility of the personnel being accused of negligence (p7, p8 and p9) |

|

| Placing patient care at the highest priority |

Operational staff focus on patient care rather than reacting to family threats (p1 and p2) Paying more attention to the care of the patient in the face of severe concern of the companions (p1, p2, p3, p4, p5, p6, p7, p8, p9, p10, p18 and p22) Diverting the discussion and the controversy towards the implementation of practical actions for the patient (p1, p2, p4, p6, p8, p10, p14 and p18) Requesting the staff from the patient's companions to postpone the discussion to another time (p2, p3, p4, p8 and p9) |

|

|

Involving more reasonable companions in tension control |

Asking the calmest relatives to ventilate the patient with an Ambu bag (p4, p5, p6, p8 and p10) Asking more rational companions to quiet down around the patient (p2, p5 and p6) Obtaining cooperation from the patient's companions to move the patient faster (p2, p4, p5, p6 and p7) |

|

| Expedient lie |

Performing demonstration measures for the patient to prevent tension (p6, p7, p9, p10 and p16) Resorting to lies by the staff to keep the patient and the patient's companion calm (p6, p7 and p8) |

|

|

Persuasive communication |

Warning companions about the consequences of continued tension |

Emphasising the delay in transferring the patient if the tension continues (p2, p4 and p8) Announcing the possible risks of non-cooperation of the patient or relatives with the personnel (p2, p3, p4, p5, p6, p7, p8, p9, p10 and p13) |

| Clarify and provide alternative recommendations |

Explaining the reasons for the delay in sending an ambulance to the caller (p11, p12, p13, p4 and p8) Providing the necessary recommendations to companions who oppose the transfer of an acute patient (p6, p7, p8, p9 and p10) |

|

| Giving timely and appropriate feedback to companions |

Striving to keep the patient's companion calm by expressing the normal results of the patient's evaluations (p6, p7, p8, p14, p19, p20 and p23) Explanation about the non-acuteness of the patient's problem in response to the patient's companion concerns (p2, p14, p16, p18, p20, p22 and p23) |

|

| Assuring the patient's companions |

Showing the facilities and equipment inside the ambulance to gain the trust of the patient's companions (p8 and p22) Emphasis on taking all possible measures to gain the trust of the patient's companions (p3, p4, p8, p14, p16 and p17) |

|

| Giving hope to the patient's companions |

Promising the patient's recovery to the patient's companions to calm them down (p6, p7, p8, p16 and p22) Striving to calm the patient and the patient's companion by giving them hope (p3, p19 and p22) |

|

| Informing the patient's companions |

Informing the patient's companion of the actual response time of the ambulance to the request for emergency help (p8, p11, p12 and p13) Informing the patient's companion about decisions related to the patient to keep them calm (p3, p6, p8, p16 and p18) Explaining the reasons for the ambulance's late arrival to the patient's family (p3, p4, p12 and p13) |

|

| Providing a relatively calmer environment for the patient |

Asking the patient's companions to refrain from crying and wailing at the patient's bedside (p5, p6, p7 and p9). Moving the patient away from the noisy environment (p1, p3, p5, p6, p7 and p9) |

|

|

Forbearance |

Patience in the face of tense conditions |

Avoiding hasty reactions to the anger of the patient and the patient's companions (p6, p12, p13, p14, p16, p17 and p22) Avoiding discussion and arguing with the patient's companion to prevent the escalation of tension (p2, p8 and p9) Adapting to the insult of the complaining caller (p12 and p13) Pleasantness in dealing with patients' companions in tense situations (p2, p8 and p13) Deliberate silence against the strong protest of the patient's companions (p1, p2, p3, p4, p6, p9, p10 and p18) |

| Empathy with the patient's relatives |

Granting the right to the patient and patient's companion due to understand their conditions (p11, p17, p18 and p9) Understanding the reason for the protest of the patient's companions (p9, p11, p12, p16, p17 and p18) Expressing sympathy with the very worried patient's companion (p4, p11, p12, p19 and p22) |

5.4.1 Situational Resourcefulness

When the ambulance encountered an obstacle, I initially perceived its speed to be merely 10 kilometers per hour, prompting me to wonder why it was moving so slowly. However, the technician assured me otherwise, emphasizing the urgency of the situation. He proceeded to signal the driver to accelerate by gently tapping the rear cab of the ambulance, urging for a quicker pace. (Patient relative 22)

During emergencies, the primary focus typically revolves around implementing treatment measures for the patient. The nurse ensures to be visibly present and attentive to the patient's needs, reassuring the family that there is someone readily available to assist should any further complications arise. (Emergency nurse, p 16)

I also tried to reassure them, urging them to remain calm and composed to avoid agitating the patient further. They made an effort to regain control of their emotions. (Operational personnel, p 6)

In situations where the patient's companions are highly agitated and the risk of physical conflict is high, even if patient transfer might not be immediately necessary, we prioritize transferring the patient to ensure the safety of all involved. (Operational personnel, p 7)

Sometimes there are limitations to the interventions we can provide for the patient. Despite our efforts, it may seem like we're merely putting on a show, performing actions to reassure those around us that we're actively tending to the patient's needs. (Operational personnel, p 10)

5.4.2 Persuasive Communication

This strategy underscored the efforts of the emergency care providers during tense situations to persuade companions, alleviate their agitation and manage the tense atmosphere. They achieved this by cautioning companions about the repercussions of prolonged tension, addressing doubts and offering alternative suggestions, providing timely and relevant feedback, reassuring companions, instilling hope in patient companions and raising awareness through effective verbal communication.

We wanted to place the baby on the board, the attendants urged us to expedite and transport him to the ambulance. We clarified to them that it was essential for the baby's health; moving him incorrectly could risk severing his spinal cord. (Operational personnel, p 3)

Typically, we approach the patient's companions and reassure them by stating that there are no significant issues with the patient's ECG, indicating that the patient is currently stable. We then explain that we will conduct another ECG to further assess the situation. This transparent communication often helps to alleviate their concerns and promotes a sense of calmness. (Triage nurse, p 14)

5.4.3 Forbearance

In this strategy, the emergency care providers strived to prevent the escalation of tension through various methods, including displaying patience in stressful situations and empathising with the patient's relatives. By employing a policy of remaining silent, refraining from reacting impulsively, adapting to the current circumstances and conveying sympathy and empathy towards both the patient and companions, they exerted their utmost to minimise or resolve the tension altogether.

The family was visibly anxious, engaging in a brief argument with my colleague. Despite the provocation, my colleague calmly urged them to relax before attending to the patient. Even though the patient's companions often resorted to vulgar language, I refrained from responding. I recognized that engaging would only exacerbate the situation, so I maintained my composure and focused on my responsibilities. (Operational personnel, p 2)

While the emergency personnel may not have needed to take that particular action for my child at that moment, it conveyed a sense of shared concern, providing me with a reassuring sense that they empathized with my worries. (Patient relative, p 22)

5.5 The Outcomes of the Process

Based on participants' experiences, the personnel involved in patient transfer endeavoured to satisfy patients' relatives and diffuse tension through various means such as dialogue, warning about risks and consequences, keeping companions informed about decisions, actions, and expected outcomes and expediting patient treatment. Despite persistent efforts, they managed to persuade a substantial number of people to cooperate by implementing solutions. However, despite their best efforts, a significant number of individuals continued to engage in conflicts, arguments and debates. This often led to complaints from the patient's relatives against the personnel, which were submitted to authorities or judicial institutions. All these efforts to control tensions led to five overarching consequences, categorised as ‘successful persuasion’, ‘failed persuasion’, ‘escaping from responsibility’, ‘long-lasting hidden tension’ and ‘surrendering’.

5.5.1 Successful Persuasion

It involved providing patients' relatives with clear explanations from personnel, calming them down through practical measures for the patient resulting in improved conditions, and garnering trust and cooperation through personnel decisions during the transfer process.

I informed the patient's companion that if I were to transfer the patient at a speed of 120 kilometers per hour, I would be unable to prioritize any of these crucial actions. The patient's companion expressed satisfaction with my explanation. (Operational personnel, p 7)

5.5.2 Failed Persuasion

Despite the personnel's success in persuading many companions and effectively managing tense situations using diverse strategies and measures in various instances, there were still numerous cases where the patient's companions remained unconvinced.

I try to explain to them that although it may feel like a long time, the ambulance will take some time to arrive. While some individuals accept this explanation, others become agitated and express frustration, swearing, and questioning why the ambulance took so long when it should only take two minutes. (Dispatcher, p 13)

5.5.3 Escaping From Responsibility

The personnel involved in patient transfer did not attempt to persuade them in the face of companions' opposition to the patient transfer, driven by a desire to depart the location swiftly or in response to pressure from companions to expedite patient transportation to healthcare centres.

The patient is akin to a fireball; if you attempt to hold it, you risk getting burned. Therefore, it's crucial to reject this ‘fireball.’ Whether you choose to place it in the hands of the consulting doctor, the treatment center, or the patient's relatives, the decision ultimately rests with you. (Operational personnel, p 10)

5.5.4 Long-Lasting Hidden Tension

Sometimes I'm riding the subway or the bus, I find myself feeling stressed when I hear a phone ring, especially if it sounds like the tones we use in our workplace. It triggers memories of past missions, causing my heart rate to increase. (Operational personnel, P 4)

5.5.5 Surrendering

Despite the severity of the patient's condition, companions may insist that it is not serious, leading to the decision not to transfer the patient. (Operational personnel, p 9)

5.6 Brief Storyline

Despite the diligent efforts of the emergency care providers to transfer patients responsibly, they encountered highly anxious patients' relatives and companions who exerted pressure to expedite transportation to medical centres, resorting to threats, insults, intimidation and sometimes even violence. In response, the personnel employed various strategies, prioritising patient needs, practising silence, patience and empathy in the face of hostility, informing companions about actions and decisions and involving them in the transfer process. They avoided confrontations that could escalate tension, aiming to successfully persuade companions and manage the situation. However, in some instances, the providers might relinquish their professional stance and expedite patient transfer to healthcare centre personnel to alleviate responsibility. Repeated exposure to such encounters could lead to lasting adverse psychological effects on emergency care providers.

5.7 The Central Variable and Integration of the Categories

Emergency care providers, throughout all stages of the patient transfer process, work diligently to address patients' care and treatment needs. They seize every opportunity for involvement and rely on the support of the patient's companions and relatives to expedite the transfer. While family involvement helps meet the patient's biomedical needs and ensures a safer transfer, providers still face the pressure of delays and the threat to patient survival during pre-hospital emergency transfers. A careful examination of this situation, along with a review of relevant notes and theoretical considerations, allows for the identification of underlying causes, an analysis of the strategies used to manage tension and an exploration of the positive and negative outcomes of these strategies. Additionally, we must consider the factors that either facilitate or hinder effective tension management.

From this analysis, the concept of ‘diligent avoidance of tense confrontation’ emerges as a central variable. This concept encapsulates the collective efforts of all those involved in the patient transfer process, who confront the tension of delays and patient survival threats. It highlights a conscious, deliberate effort to avoid confrontations that could escalate tension. In summary, emergency care providers strive to prevent reactions or confrontations that could intensify tension during patient transfer. Ultimately, the theory of diligent avoidance of tense confrontation in the patient transfer process was developed through the integration and refinement of these concepts (Figure 2).

6 Discussion

The objective of this study was to explore the patient transfer process from pre-hospital to the hospital emergency department, identify the areas of concern in this process and strategies that emergency care providers used to address these concerns. The data analysis revealed that the primary concern of the emergency care providers was the tension of delay in safe patient transfer and patient survival threat. While they maintained their focus on the provision of care to the patient by using the main strategy of diligent avoidance of tension-causing confrontation, they made efforts to manage tension and transfer the patient safely. In this basic psycho-social process, some factors act as facilitators and others are barriers. Time is a crucial role in the effective management of high-risk health situations (Herlitz et al. 2010; Collet et al. 2018). The critical and unpredictable condition of patients exacerbates families' distress. Also, any delay in the provision of emergency care becomes intolerable, fostering dissatisfaction and sometimes even erupting into extreme acts of violence (Nord-Ljungquist et al. 2020). Pre-hospital delay, defined as the time elapsed from the onset of symptoms in a patient to the receipt of definitive care (Alidoosti 2004), has been identified in prior research as a primary or pre-disposing factor for the emergence of violence and aggression in emergency situations (Rees et al. 2023; Bernaldo-De-Quirós et al. 2015; Sheikh-Bardsiri et al. 2013). This issue can occur as a result of the difference between what is desirable and what can be achieved in reality (Dollard et al. 2013).

In this study, unreasonable expectations and lack of public awareness were among the underlying factors of tension. Since any event that requires an emergency response by an ambulance can be very stressful for the people involved (Nord-Ljungquist et al. 2020), extreme stress and anxiety of relatives are considered one of the main reasons for acts of violence (Karlsson et al. 2020). In contrast to this finding, Philippe Charrier et al. showed that violence and conflict are not always related to the anxiety of patients or their companions, but the patients or their relatives do not have the basic etiquette necessary to interact with others (Charrier et al. 2021) caused by their ignorance of the appropriate methods of interaction in emergencies. In any setting where interaction and communication occur, conflict and disagreement are bound to arise, particularly in pre-hospital emergencies where time is constrained and communication spans across diverse professional backgrounds (Karlsson et al. 2020; Bremer et al. 2009a).

This study revealed that pre-hospital delays stemmed from a spectrum of reasons. Tangible factors such as unclear patient addresses, traffic impediments, and inadequate transportation resources both ground and air as well as staff negligence contributed to these delays. The emergency care providers employed various strategies, including making contingency decisions, to mitigate these issues. However, unrealistic factors such as ignorance, negative attitudes and lack of trust in personnel competence often triggered significant stress among patients' families. Consequently, anxiety surrounding delayed safe transport and the threat to patient survival intensified. Similar studies also showed that the process of transferring a loved one affects the whole family, so they experience various negative emotions (Herlitz et al. 2010). They experienced a range of extreme emotions from hope to despair (Bremer et al. 2009a), from calmness to chaos (Nord-Ljungquist et al. 2020) and confusion and disturbance (Jarneid et al. 2020; Paavilainen et al. 2017). Therefore, they perceived the elapsed time differently than the actual time (Huabbangyang et al. 2022). In these unstable conditions, both the patient and their relatives find themselves in a state of vulnerability and incapacity (Bremer et al. 2009b; Holmberg et al. 2016), necessitating assistance and support as fellow human beings (Gustafsson et al. 2013). While emergency care providers are tasked with making rapid decisions and ensuring proper patient care, the anxiety and distress experienced by the patient's relatives add an extra layer of responsibility and care burden for them to manage (Kamphausen et al. 2019). Hence, the presence of family members during emergencies imposes significant responsibilities on personnel, demanding the capacity to recognise, adapt decision-making processes and respond effectively to their needs. The shift from patient-centred care to family-centred care necessitates a transition from a structured response to a more situational one, where personnel must navigate a delicate balance between rational decision-making and emotional responsiveness based on the circumstances at hand (Gallo et al. 2016). However, sometimes due to feelings and emotional reactions, personnel cannot afford to prioritise these responsibilities selectively in their decision-making processes. Failing to do so puts them at risk of reaching incorrect conclusions and fostering caregiving relationships based on false elements such as unrealistic hopes (Bremer et al. 2012).

In this study, the utilisation of expedient lies by the emergency care providers, such as the unrealistic and demonstrative performance of cardiopulmonary resuscitation on a deceased patient, aimed at instilling hope among the patient's companions. As noted in this research, amidst the tense atmosphere, the emergency care providers bolstered the level of support provided to patient companions by leveraging resources such as experience, professional demeanour and appearance. Additionally, they employed the strategy of skilful avoidance of confrontations that could escalate tension as a primary tactic for tension management. This strategy is consistent with the belief of emergency personnel in refraining from reactive measures and prioritising the respect for the rights of patients and their families as the utmost form of response (Sheikhbardsiri et al. 2022). In line with the main request of the patient's relatives, they diligently tried to speed up the patient transfer process by using strategies such as focusing on immediate vital actions for the patient and safe transfer of the patient as their main mission and using strategies such as expediency, patience and establishing persuasive communication to reduce the tension as much as possible and safely transfer the patient to health care centres. Previous studies also show that where ambulance personnel communicate more effectively with the patient's relatives, they feel informed and included in the care process. In contrast, in instances where inadequate communication is reported, families often experience feelings of confusion and isolation (Gallo et al. 2016).

In this study, the emergency care providers tried to calm the patient's relatives and obtain their cooperation by keeping the relatives constantly informed about the patient's condition and giving timely and appropriate feedback. These efforts, along with the influence of various intervening factors, ultimately led to gaining the trust of patients and their companions and calming them down. In many other cases, these approaches may prove ineffective, leading to consequences such as unsuccessful persuasion, acquiescence to unprofessional demands from attendants and attempts to shift responsibility for the patient's care by expediting their transfer to healthcare centres. While providing honest information and instilling a sense of hope, along with reassuring the patient's relatives about the quality of care being provided, can indeed enhance their ability to cope with anxiety and stress (Dadashzadeh et al. 2019). Nevertheless, effective communication and cooperation in emergency situations can be disturbed due to a lack of trust, unfavourable perceptions and high expectations of patients and their relatives (Afshari et al. 2023). Based on existing evidence, one solution employed by emergency care providers to disengage from stressful situations involves physically removing themselves from the scene to avoid potential confrontation (Charrier et al. 2021; Dadashzadeh et al. 2019).

Our finding also showed that when the personnel were not successful in managing the tension, they tried to alleviate the pressure from companions by expediting the handover of the patient to emergency department staff, aiming to minimise the duration of direct interaction and the associated stress. However, this approach can lead to conflict and disruption of communication between the employees of these two departments, along with the complex and often chaotic nature of the emergency department (Owen et al. 2009). It has the potential to seriously endanger the exchange of important patient information and jeopardise patient safety (Bost et al. 2012; Safety and Care 2010).

This study revealed that surrendering to the unprofessional demands of the patient's companions is a consequence of ineffective efforts by emergency care personnel to control tension. While this approach may prevent the continuation of the tension at the moment, it can have adverse psychological effects (Gusmão et al. 2018) on emergency care providers and, in the long run, has a high potential to reduce job satisfaction and cause turnover (Dadashzadeh et al. 2019).

The failure of strategies to manage tension resulted in long-term hidden tension according to our findings. Emergency care providers are often subjected to high-stress situations, which means that they are susceptible to experiencing stress like patients and their relatives. The emotional weight of being first responders at the forefront of the healthcare system heightens the risk of secondary trauma, a type of stress induced by assisting individuals in distress (Regehr, Goldberg and Hughes 2002; Regehr, Goldberg, Glancy, et al. 2002). This finding confirms that emergency care providers are at risk of compromised psychological safety due to their daily exposure to stressful factors (Regehr 2005; Alexander and Klein 2001). Consequently, this can have a detrimental impact on the long-term quality of emergency care (Hadian et al. 2022). Hence, policymakers must give particular attention to this issue and devise solutions to mitigate its effects.

7 Strengths and Limitations

According to our knowledge, this is the first study to comprehensively investigate the main concerns and management strategies during the patient transfer process from pre-hospital to the hospital emergency department. The study involved all parties involved in patient transfer, including hospital emergency personnel, pre-hospital personnel, patients and their relatives. This facilitated the attainment of a more thorough and precise understanding of the complexities involved in patient transfer by emergency care providers, aiding in the development of suitable strategies to address them. One limitation of this study is that while the main author had frequent access to the hospital emergency environment for collecting documents and observing patient delivery processes between pre-hospital emergency personnel and hospital emergency departments, similar access was not available in the pre-hospital environment. The main author could only attend the telephone communication centre and pre-hospital emergency bases in limited cases.

Recommendations for further research: Further research should explore patient- and family-centred care during transfers, examine verbal and non-verbal communication strategies, develop evidence-based guidelines for assessing and mitigating transfer risks, and assess whether specialised training in transfer procedures, communication skills, and conflict resolution enhances outcomes.

8 Conclusion

The patient transfer process in pre-hospital emergencies typically commences with a call for assistance from non-professional individuals at the scene and ideally concludes with the safe handover of the patient to specialised healthcare facilities by professional ambulance personnel. Throughout this transfer, these professionals face pressure from the patient's relatives to expedite the transfer to healthcare centres, often enduring insults, threats and even violence. Consequently, they must transition from a patient-centred to a family-centred approach, which transcends mere clinical knowledge and technical expertise.

Emergency care providers encounter various tensions during this process, with the delay in safe transfer and the threat to patient survival emerging as primary concerns. In response, they employ diverse strategies, yielding outcomes ranging from positive to negative. While positive strategies contribute to the development of clinical guidelines for real-world scenarios, negative consequences such as communication breakdowns, relatives' refusal to cooperate with pre-hospital emergency services, formal complaints, surrendering, shifting patient responsibility and prolonged underlying tensions underscore the urgent need for effective support and more efficient tension management strategies for emergency care providers during patient transfer.

Author Contributions

The authors contributed to the design and implementation of the research, to the analysis of the results and to the writing of the manuscript. M.J., F.A., M.K., M.V.: Study design and conceptualization. F.A.: Data collection. M.J., F.A., M.K., M.V.: Data analysis and interpretation. M.J., F.A., M.K., M.V.: Manuscript writing. F.A., M.K., M.V.: Study supervision.

Acknowledgements

This article is one part of the nursing doctoral thesis of the first author, which was approved by the Medical Ethics Committee of Tarbiat Modares University, Tehran, Iran. The authors are grateful to all participants who shared their valuable experiences.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Open Research

Data Availability Statement

Due to the qualitative nature of the data collection and in consideration of the anonymity and confidentiality of the participants, access to the data set utilised in this research is restricted.