‘I need support in becoming the leader I would like to be’ – A qualitative descriptive study of nurses newly appointed to positions of leadership

Abstract

Aim

The aim of the study was to understand the experiences of nurses who were newly appointed to a position of leadership including facilitators and barriers to success and what they considered important for the development of their role.

Methods

We used a qualitative descriptive research design. The study was conducted in Norway with 10 nurses who had been appointed to a leadership position within the last 2 years. Participants were interviewed with individual qualitative interviews which were transcribed and subsequently analysed using thematic analysis.

Results

The following four main themes were identified from the data: I feel lonely in the leadership position, I am not confident as a leader, I am unsure of the requirements and expectations of me, and I need support and supervision.

Conclusion

The results underscore the challenges reported by new leaders in nursing and their advocacy for mentorship as a facilitator for success. The qualifications of mentors were emphasised with a need for a comprehensive leadership skill set to address the multifaceted aspects of leadership development.

1 INTRODUCTION

Experienced leadership has been studied among nurses, with some studies suggesting that nurses in general, and in a variety of healthcare contexts, experience difficulties in positions of leadership (Arnetz et al., 2020; Solbakken et al., 2018; Sundberg et al., 2022). It may be the case that nurses, as leaders, experience a strong sense of responsibility for the quality of the care they deliver, but may have difficulty defining their leadership role (Kelly et al., 2019). It also emerges, however, that nurses experience difficulties in making decisions in relation to patient concerns, partly because it is beyond their remit and partly due to feelings that they lack competence (Lysfjord & Skarstein, 2023; Rosser et al., 2023). Further, if nurses are not confident in their leadership role, this will negatively impact their staff, which may in turn have a negative effect on patient care (Solbakken et al., 2018). Within psychiatric care, specifically, ambivalence in the leadership role is found to be prominent among nurses; feelings of responsibility and meaningfulness are mixed with a sense of both powerlessness and uncertainty (Solbakken et al., 2018; Sundberg et al., 2022). Psychiatric nurses, more commonly named mental health nuses (MHNs), in leadership roles may feel a lack of authority in leading psychiatric nursing care, which may increase feelings of uncertainty in their role (Lysfjord & Skarstein, 2023; Sundberg et al., 2022). Leadership which cultivates a collaborative and supportive working environment is associated with higher staff satisfaction (Bergstedt & Wei, 2020). Further, such leadership has been found to reduce turnover among MHNs and increase patient satisfaction with their treatment (Moloney et al., 2020). Therefore, understanding factors that contribute to excellence in nursing leadership is fundamental to ensuring an ongoing development in the profession and who can positively influence outcomes for both healthcare providers and patients (Baek et al., 2020; Rosser et al., 2023). Mentoring can possibly be an effective intervention (Grocutt et al., 2022; Rosser et al., 2023). It has been defined as a relationship between a senior and a junior member of staff for the purpose of offering experience-based discussions which might include reflection, emotional support and other assistance for the career advancement of novices as well as leaders (Grocutt et al., 2022). Mentoring has also been found to have positive influence on research productivity, leadership skills and knowledge among nurses (Hafsteinsdóttir et al., 2020). Furthermore, mentoring has proven to positively influence health and well-being, staff relationships, work culture and collaboration (Pishgooie et al., 2019). Being part of a mentoring programme can result in improved communication and a more supportive culture. These changes also contribute to better patient satisfaction (Le Comte & McClelland, 2017). Therefore, mentoring programmes are promising arenas for developing leadership capabilities (Grocutt et al., 2022). Further, such programmes differ from short attendance courses and require a longer-term commitment on the part of both individuals and their organisation (McNamara et al., 2014; Vitale, 2018). In mentoring it is recommended that the focus should be on each participant's current role and everyday practice and on helping the participant to develop and demonstrate clinical leadership skills in these contexts (McNamara et al., 2014). This type of support, therefore, offers development that cannot be found in others forms of training.

To support nurses as leaders and to underpin good leadership in mental health care, knowledge is needed regarding the experiences and challenges of MHNs who are newly appointed to positions of leadership. However, there is scant literature on this topic including a lack of information about factors with which new leaders struggle, and what they believe a mentoring programme should offer to improve their competencies. Such knowledge might facilitate the development of personalised mentoring programmes for new leaders in nursing. This study aims to address these issues, taking Norwegian circumstances as a point of departure.

2 METHODS

2.1 Aim

The aim of the study was to understand the experience of nurses newly appointed to a position of leadership and to address what they considered to be important for their development, including factors which may be considered as facilitators or barriers to success. The findings will be applied to the further development of The Norwegian Nurses Organisation mentoring programmes for nurses in leading positions (hereby called nurse leaders).

2.2 Study design

A qualitative descriptive design using semi-structured interviews (Elliott & Timulak, 2021).

2.3 Setting and participants

The Norwegian Nurses' Association established a mentoring programme for nurses who are new in a leading position in 2020 (Lysfjord & Skarstein, 2023). In this programme, experienced leaders in nursing with clinical backgrounds and supervision competence contribute to the development of recently appointed (novice) leaders. Such novice leaders can apply to participate. Those with <2 years in the role and responsibility for nursing staff are prioritised. The inclusion of leaders from different regions of the country are encouraged.

In this study, 10 nurses who had recently been appointed to a leadership position were included, see Table 1. All were female, aged mid-30s to 60 years (mean 42) and had voluntarily applied for participation in the Mentor programme. All participants included were interviewed even though saturation occurred after six interviews, with many similarities in the meaningful quotes which underpinned the themes that became visible. It was considered a strength to have these themes confirmed by all participants.

| Code | Gender | Age | County | Specialised in mental health care | Level of leadership education |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| P 10 | Female | 32 | Northern Norway | Yes | Master of management |

| P 11 | Female | 44 | Southern Norway | Yes | Internal leadership programme |

| P 12 | Female | 36 | Northern Norway | Yes | Leadership education |

| P 13 | Female | 48 | Eastern Norway | Yes | Master of management |

| P 14 | Female | 52 | Western Norway | Yes | Internal leadership programme |

| P 15 | Female | 48 | Western Norway | Yes | Master of Management |

| P 16 | Female | 46 | Mid Norway | No | Internal leadership programme |

| P 17 | Female | 33 | Mid Norway | Yes | Internal leadership programme |

| P 18 | Female | 38 | Eastern Norway | Yes | Leadership education |

| P 19 | Female | 35 | Northern Norway | Yes | Leadership education |

| P 20 | Female | 50 | Southern Norway | Yes | Internal leadership programme |

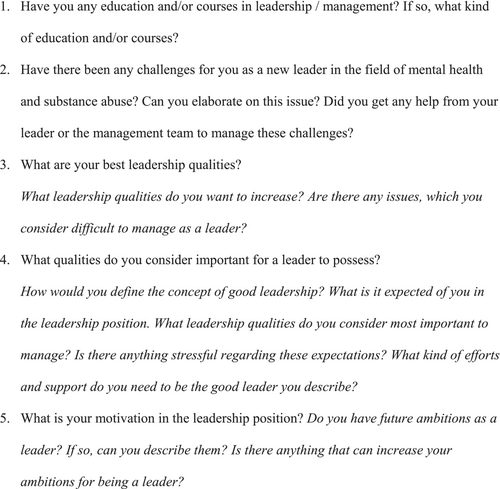

2.4 The interview guide

The research team developed a semi-structured interview guide (Figure 1). This team consisted of one professor, two associate professors and three nursing managers. All the researchers were nurses. The research team conducted a comprehensive review of literature focusing on nurses in leadership roles. Based on this, pertinent questions to gain insights into the experiences of nurses newly appointed to leadership positions and to address what they considered to be important for their development, including factors which may be considered as facilitators or barriers to success. The guide asked nursing leaders about their thoughts, feelings and skills specific to their new leadership role.

2.5 Data collection

Data were collected through individual telephone interviews. One interviewer (MS) with substantial experience in mentoring conducted all the interviews. Semi-structured questions were asked, such as ‘What are the main challenges for you in the leadership position?’ The participants were also asked to elaborate upon efforts they considered supportive in the development of their leadership skills. Each interview lasted approximately 45 min. The interviews were transcribed for accurate analysis. The interviewee responses were noted and repeated, allowing misunderstandings and ambiguities to be uncovered and corrected. All interviews were anonymised, coded and analysed. The list of codes was kept in a separate safe in a separate room at Oslo Metropolitan University. Only one professor in the research group had access to the code list.

2.6 Data analysis

We used the six-step process for thematic analysis described by Clark and Braun (Clarke & Braun, 2017).

2.6.1 The analysis processes

First, the authors (SS and EML) read and reread each interview separately. In the second step, each author separately coded significant features of the data and collated relevant data to each code in a systematic table. They then went on to separately collate the data into potential themes, before reviewing them and checking that they were logical in relation to the data material. Further, each of the authors defined and named the themes. After this preliminary analysis process, the authors met and coordinated their analysis and results. To illustrate each theme quotes were discussed and selected, see Table 2.

| 1. Familiarisation with the data material | Each author read and re-read the written interviews |

| 2. Generating initial codes | Each author coded interesting features of the data material |

| 3. Searching for themes | Each author collated codes into potential themes and gathered all data relevant to each potential theme |

| 4. Reviewing themes | The authors separately collated the data into potential themes and reviewed these themes by checking that they were logical in relation to the data set |

| 5. Defining and naming themes | Ongoing analyses were conducted by both authors (EML and SS) when they met for analysis sessions. The themes were discussed and agreed upon at these sessions |

| 6. Producing the report |

Themes were reduced and clustered under four main themes. Quotes were selected and agreed upon to illustrate each theme Vivid and compelling extracts were then selected, a final analysis was conducted of selected extracts, the analysis was related back to the research question and literature, and a report was developed showing the analysis process |

The data were analysed according to the principles of thematic analysis outlined by Clarke and Braun (2017). The six steps of the analysis process were performed, and codes and themes were derived (Table 2).

2.7 Trustworthiness

Trustworthiness is a concept widely used instead of validity and reliability when reporting the findings from qualitative studies (Clarke & Braun, 2017). For the reader to be able to determine whether the results of this study are transferable to other contexts, a description of the context, selection and demographics of the new leaders, the data collection process and analysis process has been described. Once the final themes were established, we started the process of writing up the reports. Shorter quotes within the narrative were included in the findings, and all quotes were accompanied by a unique identifier to demonstrate that various participants were represented across the results. We also presented themes, subthemes and exemplar quotes in a table which aided us in keeping the report within journal word limits. The identified themes were discussed in the final discussion section of the manuscript.

2.8 Ethical considerations

Permission was obtained in 2020 from the Norwegian Centre for Research Data (NSD), study reference; 386,161. Before the study began, the participants gave oral and written informed consent to participate. Participants were informed about the research and its purpose, that they had the opportunity to withdraw at any stage of the study, and that the data collected would be treated confidentially. Personally identifiable information was coded and removed prior to analysis and publication.

3 RESULTS

The results are based on interviews with 10 female nurses who had recently been appointed to a position of leadership in the mental health sector. They are leaders in an intermediate position between employees and senior management. All had an education in specialist nursing in the field of mental health and/or substance abuse. Nine of the 10 had an education in management, of which three were at master's level. Several had taken their institution's management programme. The nurses were leaders of units specialising in mental health and substance abuse within the special health service or in the primary health services. The following four thematic areas summarise and describe the experiences of the nurses in their leadership positions.

3.1 Theme 1: I feel lonely in the leadership position

One main theme raised was the experience of feeling lonely in the leadership position. A lack of close collaboration with others regarding their challenges and possibilities in the leadership position were perceived as a strain. Examples of the new leaders' responses to question 2 in the interview guide: ‘Have there been any challenges for you as a new leader in the field of mental health and substance abuse?’ were: ‘I am very lonely’ (P12) and ‘I need someone to lean on – a mentor’ (P17).

3.2 Theme 2: I am not confident as a leader

I want to be more confident in the leadership role (P17)

I need to become aware of my potential in the leadership role (P16)

I have a long career as a nurse, but I am very alone as a manager, no one from higher management to discuss with, I am unsure if I am a good manager (P12)

Insecurity in relation to the exercise of the leadership role appeared to inhibit the new leaders confidence.

3.3 Theme 3: I am unsure of requirements and expectations of me

There's a lot of stuff to deal with – many units and tasks, it's challenging to find my role. It's unclear what my responsibility is, both internally and externally (P10)

I feel thrown into the job. It is expected that you can do everything right away, even if there is a lot to familiarise yourself with. There are big challenges as a new leader (P13)

3.4 Theme 4: I need supervision. I want to reflect and discuss

I want to develop as a leader (P16)

I need supervision, and I want to discuss confidential matters with someone, without this leading to any negative consequences for my career as leader (P18)

I need someone who I can discuss with, someone who can see me from a new perspective (P14)

I would like to be more direct – say “no” sometimes. That's difficult (P15)

The new leaders need for support ranged from personal development in the form of increased self-insight and handling conflicting interest within their units, to gaining a professional leadership network. Further, they wanted to gain a meta-perspective on the exercise of the leadership role and thereby expand their competence.

3.5 I need support to be the leader I would like to be

The four themes arising from the interviews emphasise that the participants do not feel they manage the role as a leader in a way that is personally satisfying. They feel lonely in the leadership position, they are not confident as a leader, they are unsure of the requirements and expectations of them in the leadership role. All want to increase their leadership competences and acknowledge that professional leadership support might be helpful. Collectively, the four themes described above lead to a single overarching theme – ‘I need support in becoming the leader I would like to be’.

4 DISCUSSION

The newly appointed leaders in this study articulated a sense of loneliness and a lack of confidence within their leadership roles. Common themes included a lack of clarity regarding expectations and requirements from their seniors, coupled with insufficient supervision and support.

4.1 Loneliness in the leadership position

Feelings of loneliness may be an indication that the new leaders are unsure whether they cope well with the leadership role or not. When individuals move into leadership positions, they are expected to fulfil the organisation's strategic and structural needs. Such transference into the role of nursing leaders might add stress and eventual social isolation (Kelly et al., 2019; Rokach, 2014). The new leaders felt they were expected to meet the expectations from employees and at the same time fulfil the goals of the organisation (Rokach, 2014; Sundberg et al., 2022). In taking on a leadership role, they might find that one of the reasons for feelings of loneliness is that they become a target of their employees' ideals, wishes and feelings (Lysfjord & Skarstein, 2023). Rokach points out that leadership positions within organisations often fail to foster work environments where friendship and social intimacy are possible, and loneliness may therefore develop (Rokach, 2014). However, this study also states that when no one is available to respond to the leader's needs for company and support, they may experience loneliness, which may trigger and underpin stress (Rokach, 2014).

4.2 Role ambiguity

Some participants express that their leader or leadership team is not sufficiently available to discuss challenges and offer professional support. This underpins feelings of insecurity about how tasks are expected to be handled in the best way for supporting a good working environment for the employees, provide patients with good nursing and care, keeping budgets and for fulfilling the organisations strategy. If such conditions and insecurity persist over time, it can trigger negative physical and emotional responses and cause stress. This in turn can lead to unfortunate consequences for both the individual and the organisation (Ghanayem et al., 2020). It is, therefore, appropriate to map and prevent situations where requirements and expectations are unclear and might possibly exceed a leader's resources (Cummings et al., 2021). The systematic inclusion of such preventive efforts and activities in a mentoring programme could, be a profitable measure (Grocutt et al., 2022).

The new leaders struggled with the experience of uncertainty in relation to demands and expectations. This uncertainty can make them unsure about their own mandate to lead within psychiatric nursing care (Sundberg et al., 2022). Some participants lack necessary information to perform as a leader and they do not have a clear idea of what is required. This might underpin feelings of low confidence in the leadership position. In a clear and distinct role, a leader will have sufficient information and know what work requirements are needed to perform the relevant role (Cummings et al., 2021; Kelly et al., 2019).

4.3 Role conflict

While role ambiguity is about inadequately defined tasks, role conflict is about conflicting demands in the leadership role (Haahr et al., 2020). The quote ‘I would like to be more direct – say “no” sometimes. That's difficult’ illustrates attempts to avoid conflicts. Role conflict can be understood as an individual's experience of receiving incompatible or conflicting expectations (Brough et al., 2020). Such conflict might arise when the leader experiences conflicting expectations from senior management, employees, patients and others, where the fulfilment of one expectation makes it difficult or impossible to fulfil another expectation, or when the leader's expectations do not correspond with the employees or senior managers perception of the leadership role (Dall'Ora et al., 2020; Sundberg et al., 2022). Experiencing role conflicts can create emotional reactions that can reduce job satisfaction and trust in the organisation, as well as increase work-related tensions. Several different role conflicts can be distinguished, including personal role conflict and inter-role conflict. In a one-person role conflict, the individual experiences a conflict between their inner standards or values, and the expected role behaviour (Sagiv & Roccas, 2021). Such a conflict can arise when an employee is asked to do something that goes against his or her opinions and values. Inter-role conflict occurs when an employee fills two or more roles that are incompatible with each other. The roles often require different or conflicting behaviours where the employee does not have the opportunity to satisfy everyone (Pishgooie et al., 2019; Sagiv & Roccas, 2021). In this context, it would be useful for the newly appointed leaders to receive support in clarifying issues regarding their own values and others' expectations. Further, to clarify important tasks and expectations erelating to their leadership role.

4.4 High workload

The newly appointed nurse leaders highlighted their high workloads. The reorganisation of the health sector in Norway during the last 20 years, has increased the general tasks and responsibilities of nurse leaders in relation to finances, service planning and human resources. Our finding is in line with the Norwegian Nurses' Association's management survey for 2021, which shows that more than half of nurse leaders have neither enough employees nor a sufficient financial framework to ensure good quality of services (Kaupang, 2021). MHNs, in general, work in diverse environments with a range of different patients who have complex and sometimes conflicting interests and requirements (Foster et al., 2021; Haahr et al., 2020; Yao et al., 2021). Despite this, nurse leaders in mental health are required to manage change constructively, strive for clinical excellence, and have the confidence to challenge and motivate their staff to work respectfully, effectively, and responsively, both with each other and with their patients (Baek et al., 2020; Lysfjord & Skarstein, 2023). This might be a reason for new leaders experiencing stressful high workload.

4.5 Stress

The new leaders are well educated and have a strong desire to be good leaders. They are leaders in an intermediate position between employees and senior management. Loneliness in the leadership role, unresolved expectations and demands, lack of support staff, role ambiguity, ethical dilemmas and personal conflicts combined with lack of leadership support might result in job related stress. Such stress can be a condition that occurs when the interaction between the individual and the environment leads to the individual experiencing a discrepancy between requirements and their own resources (Folkman, 2011). Stress might cause several unfortunate outcomes, including absence, reduced efficiency and performance, and burnout (Foster et al., 2020). It might be important for organisations to initiate measures to reduce stress. Stress is not inherent in the environment or in the person alone, but a result of the ongoing relationship between the two. However, stress in the leadership position is not entirely negative and can, in fact, act as a driving force for learning and development (Fletcher & French, 2021). This includes an understanding of the interactions between an individual, and his or her environment, as well as the underlying psychological processes (Fletcher & French, 2021; Folkman, 2011; Foster et al., 2020). As nurses and fellow human beings, it is important to be compassionate about people in general, but at the same time, the leadership role requires that tasks are prioritised, and available resources utilised to fulfil the strategic goals of the organisation. For some this may lead to ethical dilemmas and a devaluation of the professional role as a nurse (Kirchhoff & Karlsson, 2019). Among nurses in psychiatric care ambivalence in the leadership role is found to be prominent (Sundberg et al., 2022). Role stress among newly appointed nurse leaders can be reduced if they receive more feedback which is perceived as social support, as well as task and emotional recognition from their colleagues. For employees who experience a high degree of role stress, a supportive environment has been found to help preserve organisational commitment (Kelly et al., 2019). Such supportive social relationships will make the individual feel valued in their work, and a part of a larger network with a common commitment. There are measures that can prevent loneliness and thereby stress in leadership positions (McNamara et al., 2014; Rokach, 2014). Nursing leaders should require support in their role to identify and cope with stressors and reduce stress. This will enable them to utilise their potential for the benefit of the organisation and its users. Mentoring can be such an intervention (Grocutt et al., 2022; Hafsteinsdóttir et al., 2020; McNamara et al., 2014).

4.6 Support to develop as leaders

The newly appointed leaders expressed a need for development as leaders through supervision, reflections and discussions. Others have also found evidence that nursing leaders lack support and guidance to manage the challenges inherent in the role, such as productivity, job satisfaction and retention concerns (Kelly et al., 2019; Vitale, 2018). Nursing leaders should be supported in an effort to retain nurses, and to ensure high-quality patient care (McNamara et al., 2014; Rokach, 2014). This highlights the need for skills development and support to attain success. Studies which seek to examine how frontline managers can be retained have identified themes relating to workload responsibilities and work–life balance (Kelly et al., 2019; Moloney et al., 2020). Current evidence-based strategies for nurse retention focus on specific leadership behaviours, which creates a positive correlation between employee satisfaction and, ultimately, organisational commitment. Areas that facilitate retention are autonomy, recognition and communication (Le Comte & McClelland, 2017; McNamara et al., 2014).

The importance of mentoring has transcended all areas of nursing and is supported by numerous professional nursing organisations. The nursing profession needs to commit to and embrace the concept of mentoring to provide new appointed leaders with supportive environments (Lysfjord & Skarstein, 2023; McNamara et al., 2014). When an organisation promotes leadership development through mentoring, it may improve planning and retention of not only its nursing leaders, but also its frontline staff (Vitale, 2018). This indicates that it is appropriate to have a mentor with a background in nursing who comes from outside the new leader's organisation. This would ensure that they could be both understood professionally and at the same time have possibilities to freely discuss and reflect. However, a mentor should be someone who has both a broad insight into leadership within the health services and who is familiar with political and professional issues (Lysfjord & Skarstein, 2023; Vitale, 2018). Mentoring is an invaluable tool for the future of nursing leadership and should be highly regarded as a way to promote and support nursing leaders; a mechanism critical to the future of the nursing profession (Rosser et al., 2023). However, being a mentor who contributes to a new leader's development requires insightful pedagogical abilities (Le Comte & McClelland, 2017; Lysfjord & Skarstein, 2023). Individual preferences and the preconditions of the environment must also be carefully and respectfully considered in such a development process (Moloney et al., 2020). Further, a mentoring programme must be recognised and supported by healthcare organisations as a strategy to attract and retain nursing leaders (Rosser et al., 2023).

4.7 Strength and limitations

This study explores the perceptions and experiences of 10 new leaders who had applied for a place in a mentoring programme designed for nurses in a leadership position. Although the participants’ age and clinical experiences varied, their educational backgrounds were fairly similar with all having a bachelor's degree in nursing. It would have been useful to include more participants in the study but participation in the mentoring programme was the central inclusion criterion which created an inherent limitation on recruitment. Further, having male nursing leaders could have provided a broader understanding of the topic and given us an opportunity to identify possible gender differences. The newly appointed leaders who participated knew the topic of the current study was the usefulness of having a mentor which might have influenced their answers and had already decided that they thought it was a good idea to have a mentor. For example, they might have highlighted more negative issues in their leadership role. The strength of the sample is that those included came from all over the country and represented different levels of the health services. The analysis was based on a structured, recognised method and this increases the validity of the process and our results (Clarke & Braun, 2017). The sample is small and, therefore, the results cannot be generalised. Nevertheless, this study can provide useful perspectives regarding challenges which new nursing leaders may face.

5 CONCLUSIONS

Our study shows that newly appointed nursing leaders commonly grapple with feelings of loneliness and uncertainty about their role. This emotional and professional ambiguity can impact their overall effectiveness and job satisfaction. The expressed aspiration to increase leadership skills reflects a proactive approach to professional development. This desire indicates a recognition of the complexity of leadership roles and a commitment to personal and career growth. The study highlights that nurses who are newly appointed in leadership roles have a desire to enhance leadership skills, boost confidence and professionalise their approach which underscores the importance of targeted support. The suggestion that a competent mentor could be a beneficial solution aligns with best practices in leadership development. The common holistic skill set ensures that the mentor can not only understand the challenges faced by new leaders but also guide them in stressful ethical situations. A mentor with a nursing background, leadership experience and pedagogical skills can provide tailored guidance and support, addressing both personal and professional needs.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

All authors (SS, EML, MS, ML) have made substantial contributions to conception and design. MS interviewed the participants. SS and EML conducted analysis and interpretation of the data. All authors have been involved in drafting the manuscript and revising it critically for important intellectual content. All authors agreed to be accountable for all aspects of the work in ensuring that questions related to the accuracy or integrity of any part of the work are appropriately investigated and resolved. Given final approval of the version to be published, each author will participate sufficiently in the work to take public responsibility for appropriate portions of the content.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

The researchers would like to express their gratitude to the participating nurse leaders who generously shared their experiences of being new in leadership positions.

FUNDING INFORMATION

The study had no funding.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST STATEMENT

All authors Siv Skarstein (SS), Else Marie Lysfjord (EML), Marit Silseth (MS) and Marit Leegaard (ML) disclose any potential sources of conflict of interest.

ETHICS STATEMENT

Permission was obtained from the Norwegian Centre for Research Data in 2020, study reference 386,161. Participation required informed and signed consent.

CONSENT TO PARTICIPATE

Informed consent was obtained from all individual participants included in the study.

CONSENT TO PUBLICATION

Patients signed informed consent regarding publishing their data.

Open Research

DATA AVAILABILITY STATEMENT

The interviews are available in Norwegian. The material is coded. The material can be made available if permission is given by the Norwegian Centre for Research Data. In this case, the corresponding author must be contacted.