Psychometric properties evaluation of the Advance Care Planning Readiness Scale for community-dwelling older adults with chronic diseases residing in suburban counties within the Chinese context

Abstract

Aim

To evaluate the psychometric properties of the Advance Care Planning Readiness Scale (ACPRS-C) within the context of community-dwelling older adults with chronic diseases residing in suburban counties in China.

Design

Descriptive, cross-sectional survey.

Methods

The research method employed in this study is characterized as a methodological study. Self-reported survey data were collected among community-dwelling older adults with chronic diseases residing in suburban counties in China. Including the following psychometric characteristics, item analysis was performed using the decision value method and Pearson's correlation analysis. Content validity was assessed through expert panel evaluation. The internal consistency of the questionnaire was determined by calculating Cronbach's alpha coefficient and corrected item-total correlation. Additionally, confirmatory factor analysis (CFA) was utilized to assess the construct validity of the ACPRS-C.

Results

A total of 228 older adults participated in this psychometric study from August to October 2023. The item content validity index ranged from 0.80 to 1.00, while the scale content validity index was 0.945. The scale demonstrated excellent internal consistency (Cronbach's alpha = 0.931), and the correlation between items and total score was satisfactory. The structural validity was deemed robust (CFA model fit: chi-square/df = 1.121, comparative fit index = 0.992).

Conclusion

The ACPRS-C is a scale with strong psychometric properties to assess the ACP readiness within the context of community-dwelling older adults with chronic diseases residing in suburban counties in China. Its reliability and validity hold considerable significance for both research and clinical practice.

1 INTRODUCTION

China has become the largest country with an ageing population due to its large population base and low birth rate (Shen et al., 2022). From 2010 to 2040, the percentage of individuals aged 60 years and older in China is projected to rise significantly, increasing from 12.4% (168 million) to 28% (402 million) (Zhang et al., 2022). As life progresses, death becomes an inevitable stage, particularly for older adults who often have a high prevalence of chronic diseases (Ge et al., 2020). Supporting older adults in maintaining their health, resilience, and intrinsic capacity is crucial for successful ageing and preserving quality of life (QOL) for both individuals and caregivers, enabling autonomy, dignity, and self-esteem (Chen et al., 2023; Hu et al., 2023). Ensuring older adults receive end-of-life (EOL) care that respect their comfort and personal wishes is essential for enhancing the QOL at their EOL (Hu & Feng, 2016; Mitchell et al., 2014).

Advance care planning (ACP) is the process that adults with independent decision-making capacity, comprehend and convey their values, life goals, and future healthcare preferences to family, healthcare proxies, or medical staff regarding choices expected at the EOL (Sudore et al., 2017). ACP guarantees that medical care aligns with individual values, reducing suffering at the EOL and preserving dignity in death (Chan et al., 2014; Lum et al., 2015; Mitchell et al., 2014). ACP readiness refers to an individual's inclination and preparedness to engage in ACP (Walczak et al., 2013), playing a pivotal role in initiating ACP discussions among healthcare professionals and older adults (Zwakman et al., 2021). Comprehending the ACP readiness of older adults is directly linked to the successful implementation of ACP (Sudore et al., 2018).

2 BACKGROUND

With the accelerated ageing of population and the increasing awareness of individual sovereignty in China, the older adults are increasingly concerned about their QOL during the process of illness and their comfort at the EOL. Nevertheless, within the cultural context of China, where death is often considered a taboo participants, the medical environment and legal policies, along with public settings, discourage discussions on EOL care preference among older adults (Liao et al., 2019). Information regarding the current ACP readiness among older community residents is limited (Zhang et al., 2015). Several instruments exist for assessing the levels of ACP readiness, such as the Advance Care Planning Engagement Survey (Sudore et al., 2013), the Advance Care Planning Questionnaire (Lai et al., 2016), and the Advance Care Planning Readiness Scale (Brown et al., 2017). However, these scales are developed in other countries. Given the deeply personal and subjective nature of ACP, shaped by individual values and beliefs (Munhall, 2012), there is a pressing need for a scale tailored to the local context.

The Advance Care Planning Readiness Scale (ACPRS-C) was specifically designed to measure the ACP readiness among patients with chronic disease in China (Wang & Sheng, 2022). The overall Cronbach's alpha coefficient was 0.923, and scale content validity index (S-CVI) was 0.986 (Wang & Sheng, 2019). The ACPRS-C has been validated in urban communities and hospitals in the Chinese context, with Cronbach's alpha coefficient between 0.912 and 0.928 (Han, 2022; Yuan & Liu, 2020). However, in China, there were over 70% of older persons residing in suburban areas (Zhong et al., 2020). Therefore, the applicability of the ACPRS-C for older adults in suburban counties would need to be reconfirmed through rigorous psychometric testing. The present study aimed to evaluate the psychometric properties of the ACPRS-C within the context of community-dwelling older adults with chronic diseases residing in suburban counties in China.

3 METHODS

The research method employed in this study is characterized as a methodological study. It began with a cross-sectional approach, followed by a sequence of statistical analyses covering content validity, internal consistency, and construct validity.

This study adopted a descriptive cross-sectional design study. The selection of the suburban counties was based on the cluster sampling method. The Chengdu city comprises 14 suburban counties, known as Xindu, Longquanyi, Wenjiang, Pidu, Shuangliu, Qingbaijiang, Jintang, Pujiang, Xinjin, Dayi, Dujiangyan, Pengzhou, Chongzhou, and Qionglai (Wang et al., 2021). The city is geographically divided into eastern, southern, western, and northern regions. One suburban county was randomly selected from each region. The older adults from these four suburban counties were invited to participate in the study to ensure a representative sample from Chengdu suburban counties. The distribution of participants from each region is detailed in Table 1. Given the cultural sensitivity surrounding discussions about death in mainland China, many older adults are hesitant to engage in conversations on this participants. Convenience sampling was chosen as it allowed for the quick and easy recruitment of participants.

| Variables | Category | N | % |

|---|---|---|---|

| Gender | Male | 109 | 47.8 |

| Female | 119 | 52.2 | |

| Marital status | Single | 3 | 1.3 |

| Married | 179 | 78.5 | |

| Divorced | 7 | 3.1 | |

| Widowed | 39 | 17.1 | |

| Educational level | College and above | 9 | 3.9 |

| High School | 44 | 19.3 | |

| Secondary school | 62 | 27.2 | |

| Primary school | 113 | 49.6 | |

| Mean monthly income | <RMB 2000 | 63 | 27.6 |

| RMB 2000–RM 3000 | 68 | 29.8 | |

| RMB 3001–RM 4000 | 47 | 20.6 | |

| RMB 4001–RM 5000 | 23 | 10.2 | |

| RMB 5001–RM 6000 | 11 | 4.8 | |

| >RMB 6000 | 16 | 7 | |

| Living condition | Alone | 25 | 11 |

| Spouse | 120 | 52.6 | |

| Children | 81 | 35.5 | |

| Relative | 2 | 0.9 | |

| Number of children | None | 2 | 0.9 |

| One | 97 | 42.5 | |

| Two | 80 | 35.1 | |

| Three and more | 49 | 21.5 | |

| Self-assessment of health status | Excellent | 33 | 14.5 |

| Very good | 51 | 22.4 | |

| Good | 111 | 48.6 | |

| Poor | 28 | 12.3 | |

| Very poor | 5 | 2.2 | |

| The number of participants from each region | Eastern | 52 | 22.8 |

| Southern | 63 | 27.6 | |

| Western | 54 | 23.7 | |

| Northern | 59 | 25.9 |

Based on the recommended sample size for the scale used in the measurement study, which suggests 5 to 10 times the number of scale entries (Schreiber, 2008), the sample size for this study was estimated to be 110 to 220 cases. Additionally, following Kline's suggestion, a sample size exceeding 200 participants is recommended for more accurate confirmatory factor analysis (CFA) estimations (Kline, 2011). Considering a potential 20% of incomplete responses, 264 questionnaires were distributed in this study. The inclusion criteria for participant selection consisted of the following: (1) Chinese older adults (aged ≥60 years); (2) a medical diagnosis of any type of chronic disease including cardiovascular and cerebrovascular disease, diabetes, chronic respiratory disease, chronic nephrosis, chronic digestive disorder, and cancer; (3) those who had been aware of the medical diagnosis; (4) the mini-mental state examination >20, assessed by trained researchers (Folstein et al., 1975); and (5) have attained a primary education level. The exclusion criteria were given as follows: (1) participants who were in the acute phase of the illness or critical condition; and (2) who refused participation in this study.

3.1 Instruments

A demographic questionnaire was used to collect information about the participants' gender, marital status, educational level, mean monthly income, living condition, number of children, and self-assessment of health status.

Permission was obtained from the author of ACPRS-C, Wang & Sheng, 2022 to adapt the questionnaire to community-dwelling older adults with chronic diseases in suburban counties in China. It comprises 22 items organized into three dimensions: (1) attitude (10 items): refers to the psychological tendency to participate in ACP conversations containing subjective evaluation and acceptance. Example items: “I don't believe that ACP is meaningful to me”; (2) beliefs (7 items): refers to the confidence in the benefits of participating in informal ACP based on the judgement of personal values. Example items: “ACP helps to save time for discussing medical treatments between doctors and family members in emergencies (such as rescue)”; (3) motivation (5 items): refers to the internal drive that drives or impedes an individual's participation in ACP conversations. Example items: “I would feel calm and relieved to participate in ACP”. All questions are scored by a 5-point Likert scale (points from “1-strongly disagree” to “5-strongly agree”). The total score on the scale ranges from 22 to 110. A higher score indicates a higher level of preparedness for ACP. The overall Cronbach's alpha coefficient for the scale was 0.923, Furthermore, the Cronbach's coefficients for the attitude, beliefs, and motivation dimensions were 0.900, 0.880, and 0.835, respectively (Wang & Sheng, 2022).

3.2 Cultural adaptation

In consideration of the language conventions prevalent among older adults in suburban areas, a panel of 10 experts (3 geriatricians, 3 psychologists, and 4 senior nurses with expertise in EOL care and geriatric psychology) was invited to review and adapt the ACPRS-C for cultural appropriateness. After extensive deliberation and consultation with the experts, mild amendments in words were made. Notably, in item 3, the phrase “a life-threatening situation occurs” was revised to “when about to die”. Similarly, in entry 11, “medical preferences” was modified to “treatment”. Additionally, the term “personal dignity” in item 20 was replaced with “decency”.

3.3 Data collection procedure

Data collection took place at the health education classrooms within the chosen suburban counties health service centres between August and October 2023, using a paper version of the ACPRS-C in a self-administered manner. Each individual was allowed to submit their responses only once. Participants were given the questionnaire after obtaining their informed consent. They responded to each question anonymously based on their personal feelings and actual circumstances. Strict confidentiality measures were in place, and no personal names were requested or recorded. Each participant independently completed the questionnaire, with the researcher providing assistance in reading the words in cases where literacy posed a challenge.

3.4 Ethical considerations

Prior to the commencement of data collection, approval was sought from the Ethics Committee of Sichuan Provincial People's Hospital (No: 2023071). Interested participants received comprehensive explanations from the researchers regarding the study's objectives, the anticipated time commitment, confidentiality measures, and their right to decline participation or withdraw without the need to provide a reason at any point in time. Informed consent was obtained from all participants.

3.5 Data cleaning

A seriousness check was conducted on the 264 returned questionnaires to enhance data validity (Aust et al., 2013). Each questionnaire was meticulously reviewed upon collection, and those exhibiting conspicuous errors in participant responses were excluded. Of these, 36 sets of questionnaires were excluded (7 more than three missed items; 14 impossible combinations of age, 15 living condition conflicts over the number of children). Therefore, only 228 questionnaires were included in the analysis, with an effective response of 86.36%.

3.6 Statistical analyses

In this study, SPSS 24.0 and AMOS 26.0 (Purwanto, 2023) were used for data analysis. Descriptive statistics were displayed as Mean (SD) for continuous variables and as n (%) for categorical variables. Item analysis was performed using decision value method to divide participants into upper and lower groups based on total scale scores. To capture extreme values in the distribution, this focused analysis assigned participants with higher scores to the upper group (27th percentile) and participants with lower scores to the lower group (73rd percentile) for subsequent independent samples t-test (Moses, 2017). If the decision values surpassed 3 and p < 0.05, it indicated a clear distinction between items in the scale (Moses, 2017); Subsequently, Pearson's correlation analysis was utilized to assess the relationship between scale scores and the total score. A correlation coefficient ≥0.4 suggested that the item effectively measures what the total scale aims to measure, indicating a high degree of discrimination (Jinshan et al., 2010).

Content validity was assessed using the item content validity index (I-CVI) and the S-CVI. The 10 expert panels were asked to rate the relevance by using a 4-point rating scale (points from “1- irrelevant” to “4- highly relevant”). Content validity indexes were considered to be acceptable when I-CVI and S-CVI were at least 0.78 and 0.80 respectively (Halek et al., 2017). Internal consistency was assessed utilizing Cronbach's alpha coefficient, where a coefficient higher than 0.7 indicated acceptable internal consistency (Hajjar, 2018). The corrected item-total correlation (CITC) was calculated to ensure that each item was well connected with the entire concept, and values above 0.5 were deemed acceptable (Ho & Lin, 2010). Additionally, a meticulous evaluation, involving the systematic deletion of individual observations illustrated excellent reliability for each observed variable if potential variables reliability indices exhibited improvement (Mascha & Vetter, 2018).

CFA was employed to examine the construct validity. Various model fit indicators, following Creswell (2015) guidelines, including 1 < chi-square/the degrees of freedom (χ2/df) < 3, goodness of fit index (GFI) >0.80, adjust goodness of fit index (AGFI) >0.80, incremental fit index (IFI), comparative fit index (CFI) >0.90, tucker–lewis index (TLI) >0.90, normed fit index (NFI) >0.90, and root mean square error of approximation (RMSEA) ≤0.08. Standardized factor loadings, average variance extracted (AVE), and composite reliability (CR) were used to assess convergent validity. Standardized factor loadings >0.5, AVE >0.5 and CR >0.7 were considered acceptable (Creswell, 2015). Furthermore, if the square roots of the AVEs exceeded the correlation coefficients between the dimensions, it indicated good discriminant validity (Creswell, 2015).

4 RESULTS

4.1 Characteristics of the participants

The 228 participants' ages ranged from 60 to 91 years, with a mean age of 70.36 ± 7.71 years and a median age of 70 years. There was a nearly equal distribution of male (n = 109, 47.8%) and female (n = 119, 52.2%). Majority being married (n = 179, 78.5%), primary school educational level (n = 113, 49.6%), and monthly income between RMB 2000 – RM 3000 (n = 68, 29.8%). A total of 120 (52.6%) lived with spouse have one child (n = 97, 42.5%). A notable number of participants provided positive health assessments, with 48.6% rating their health as “good”, 22.4% as “very good”, and 14.5% as “excellent”. The detailed demographic characteristics of participants is shown in Table 1.

4.2 Item analysis of the ACPRS-C

The outcome of the independent samples t-test comparing the upper group (27th percentile) and the lower group (73rd percentile) indicated statistically significant differences, with decision values ranging from −8.497 to −13.199 (p < 0.001). Following this, Pearson's correlation analysis revealed correlation coefficients ranging from 0.534 to 0.699 (p < 0.01) (see Table 2).

| Item | Group | Mean | SD | T | p | The correlation coefficients of the scale scores with the total |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Q1 | Lower (73rd percentile) | 2.340 | 0.922 | −13.199 | <0.001 | 0.651** |

| Upper (27th percentile) | 4.320 | 0.742 | ||||

| Q2 | Lower (73rd percentile) | 2.340 | 1.055 | −12.262 | <0.001 | 0.659** |

| Upper (27th percentile) | 4.270 | 0.657 | ||||

| Q3 | Lower (73rd percentile) | 2.260 | 0.974 | −11.295 | <0.001 | 0.633** |

| Upper (27th percentile) | 4.150 | 0.884 | ||||

| Q4 | Lower (73rd percentile) | 2.320 | 0.883 | −13.852 | <0.001 | 0.681** |

| Upper (27th percentile) | 4.290 | 0.687 | ||||

| Q5 | Lower (73rd percentile) | 2.440 | 0.822 | −11.277 | <0.001 | 0.636** |

| Upper (27th percentile) | 4.150 | 0.865 | ||||

| Q6 | Lower (73rd percentile) | 2.240 | 1.035 | −11.701 | <0.001 | 0.640** |

| Upper (27th percentile) | 4.160 | 0.772 | ||||

| Q7 | Lower (73rd percentile) | 2.480 | 1.02 | −10.804 | <0.001 | 0.632** |

| Upper (27th percentile) | 4.230 | 0.756 | ||||

| Q8 | Lower (73rd percentile) | 2.420 | 0.897 | −11.984 | <0.001 | 0.631** |

| Upper (27th percentile) | 4.230 | 0.777 | ||||

| Q9 | Lower (73rd percentile) | 2.290 | 0.912 | −12.503 | <0.001 | 0.645** |

| Upper (27th percentile) | 4.240 | 0.824 | ||||

| Q10 | Lower (73rd percentile) | 2.260 | 1.007 | −13.127 | <0.001 | 0.699** |

| Upper (27th percentile) | 4.290 | 0.687 | ||||

| Q11 | Lower (73rd percentile) | 2.770 | 0.895 | −11.826 | <0.001 | 0.691** |

| Upper (27th percentile) | 4.400 | 0.613 | ||||

| Q12 | Lower (73rd percentile) | 2.840 | 0.944 | −9.874 | <0.001 | 0.623** |

| Upper (27th percentile) | 4.310 | 0.692 | ||||

| Q13 | Lower (73rd percentile) | 2.680 | 0.937 | −11.363 | <0.001 | 0.670** |

| Upper (27th percentile) | 4.370 | 0.707 | ||||

| Q14 | Lower (73rd percentile) | 2.770 | 0.913 | −10.453 | <0.001 | 0.656** |

| Upper (27th percentile) | 4.340 | 0.745 | ||||

| Q15 | Lower (73rd percentile) | 2.730 | 0.944 | −11.074 | <0.001 | 0.695** |

| Upper (27th percentile) | 4.340 | 0.651 | ||||

| Q16 | Lower (73rd percentile) | 2.500 | 1.02 | −9.379 | <0.001 | 0.561** |

| Upper (27th percentile) | 4.060 | 0.827 | ||||

| Q17 | Lower (73rd percentile) | 2.600 | 1.093 | −9.559 | <0.001 | 0.598** |

| Upper (27th percentile) | 4.160 | 0.682 | ||||

| Q18 | Lower (73rd percentile) | 2.350 | 0.96 | −11.189 | <0.001 | 0.631** |

| Upper (27th percentile) | 4.160 | 0.834 | ||||

| Q19 | Lower (73rd percentile) | 2.650 | 0.96 | −9.265 | <0.001 | 0.563** |

| Upper (27th percentile) | 4.080 | 0.753 | ||||

| Q20 | Lower (73rd percentile) | 2.390 | 1.121 | −9.288 | <0.001 | 0.606** |

| Upper (27th percentile) | 4.030 | 0.829 | ||||

| Q21 | Lower (73rd percentile) | 2.450 | 1.097 | −10.129 | <0.001 | 0.582** |

| Upper (27th percentile) | 4.160 | 0.751 | ||||

| Q22 | Lower (73rd percentile) | 2.660 | 1.007 | −8.497 | <0.001 | 0.534** |

| Upper (27th percentile) | 4.000 | 0.724 |

- ** Stands for p < 0.01.

4.3 Content validity

After careful review, the I-CVI was 0.80 to 1.00, and the S-CVI was 0.945 (see Table 3).

| Item | Expert 1 | Expert 2 | Expert 3 | Expert 4 | Expert 5 | Expert 6 | Expert 7 | Expert 8 | Expert 9 | Expert 10 | I-CVI | S-CVI |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

4 | 3 | 3 | 4 | 3 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 0.9 | 0.945 |

|

4 | 4 | 4 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 1.0 | |

|

3 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 2 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 4 | 3 | 0.8 | |

|

4 | 3 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 3 | 4 | 4 | 3 | 4 | 1.0 | |

|

4 | 3 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 1.0 | |

|

3 | 4 | 4 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 1.0 | |

|

4 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 4 | 3 | 4 | 0.8 | |

|

4 | 3 | 4 | 4 | 2 | 4 | 3 | 3 | 4 | 4 | 0.9 | |

|

4 | 4 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 2 | 4 | 4 | 3 | 4 | 0.9 | |

|

3 | 4 | 3 | 4 | 4 | 3 | 4 | 4 | 3 | 4 | 1.0 | |

|

4 | 4 | 4 | 3 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 3 | 3 | 4 | 1.0 | |

|

3 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 2 | 2 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 3 | 0.8 | |

|

4 | 4 | 3 | 4 | 3 | 3 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 1.0 | |

|

4 | 4 | 4 | 3 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 3 | 4 | 1.0 | |

|

4 | 4 | 3 | 4 | 2 | 3 | 3 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 0.9 | |

|

3 | 3 | 4 | 4 | 3 | 3 | 4 | 3 | 4 | 3 | 1.0 | |

|

4 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 3 | 4 | 4 | 3 | 4 | 4 | 1.0 | |

|

3 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 3 | 4 | 4 | 3 | 4 | 4 | 1.0 | |

|

4 | 3 | 4 | 4 | 3 | 2 | 4 | 4 | 3 | 4 | 0.9 | |

|

4 | 4 | 3 | 4 | 4 | 3 | 3 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 1.0 | |

|

3 | 4 | 4 | 3 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 1.0 | |

|

4 | 3 | 4 | 4 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 3 | 4 | 3 | 0.9 |

4.4 Internal consistency of the ACPRS-C

In this study, the overall Cronbach's alpha coefficient for the ACPRS-C was 0.931. Specifically, the Cronbach's alpha coefficients for the attitudes, beliefs, and motivation dimensions were 0.940, 0.898, and 0.888, respectively. Furthermore, all items scored above 0.60 on the CITC, ranging from 0.652 to 0.803. Additionally, after individual observations were systematically excluded, none of the potential variable reliability indices exhibited improvement (see Table 4).

| Variable | Item | Corrected item-total correlation | Cronbach's alpha without item | Cronbach's alpha |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Attitude to ACP | Q1 | 0.783 | 0.933 | 0.940 |

| Q2 | 0.779 | 0.933 | ||

| Q3 | 0.756 | 0.934 | ||

| Q4 | 0.738 | 0.935 | ||

| Q5 | 0.703 | 0.937 | ||

| Q6 | 0.756 | 0.934 | ||

| Q7 | 0.733 | 0.935 | ||

| Q8 | 0.748 | 0.934 | ||

| Q9 | 0.759 | 0.934 | ||

| Q10 | 0.803 | 0.932 | ||

| Belief in participating in ACP | Q11 | 0.778 | 0.869 | 0.898 |

| Q12 | 0.713 | 0.883 | ||

| Q13 | 0.742 | 0.876 | ||

| Q14 | 0.771 | 0.870 | ||

| Q15 | 0.733 | 0.878 | ||

| Motivation to undertake ACP | Q16 | 0.723 | 0.867 | 0.888 |

| Q17 | 0.684 | 0.871 | ||

| Q18 | 0.672 | 0.873 | ||

| Q19 | 0.660 | 0.875 | ||

| Q20 | 0.717 | 0.867 | ||

| Q21 | 0.660 | 0.874 | ||

| Q22 | 0.652 | 0.875 |

4.5 Validity of the ACPRS-C

4.5.1 Construct validity

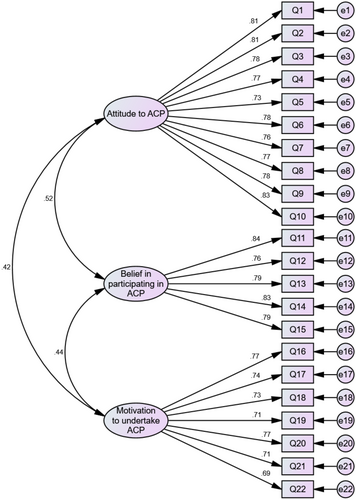

The validated factor model presented in Figure 1. The outcomes of the CFA revealed a favourable fit for the model, as indicated by a favourable fit (χ2/df = 1.121, GFI = 0.921, AGFI = 0.903, IFI = 0.992, CFI = 0.992, TLI = 0.991, NFI = 0.928, RMSEA = 0.023). Comprehensive information regarding the model fit criteria and the specific values of these metrics for the scale can be found in Table 5.

| Fitness index | Standard | Statistical value | Qualified or not |

|---|---|---|---|

| χ2/df (NC) | 1 < NC < 3 good | 1.121 | Qualified |

| Goodness of fit index | >0.80 good | 0.921 | Qualified |

| Adjust goodness of fit index | >0.80 good | 0.903 | Qualified |

| Incremental fit index | >0.90 good | 0.992 | Qualified |

| Comparative fit index | >0.90 | 0.992 | Qualified |

| Tucker–lewis index | >0.90 good | 0.991 | Qualified |

| Normed fit index | >0.90 good | 0.928 | Qualified |

| Root Mean Square Error of Approximation | <0.08 good | 0.023 | Qualified |

The results of the validated factor analysis of the ACPRS-C showed that the standardized factor loadings of items under each variable ranged from 0.694 to 0.837. The combination reliabilities for the three factors were 0.940, 0.898, and 0.889, respectively. Furthermore, the AVE values were 0.612, 0.639, and 0.533 for the respective dimensions, as detailed in Table 6. In addition to this, the square roots of the AVEs were 0.782, 0.799, and 0.730, respectively, which exceeded the correlation coefficients between the dimensions, as documented in Table 7.

| Variable | Item | Factor loading | SE | C.R. | p | CR | AVE |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Attitude to ACP | Q1 | 0.811 | 0.940 | 0.612 | |||

| Q2 | 0.807 | 0.069 | 14.115 | *** | |||

| Q3 | 0.780 | 0.071 | 13.477 | *** | |||

| Q4 | 0.766 | 0.069 | 13.131 | *** | |||

| Q5 | 0.730 | 0.067 | 12.32 | *** | |||

| Q6 | 0.779 | 0.072 | 13.454 | *** | |||

| Q7 | 0.759 | 0.069 | 12.976 | *** | |||

| Q8 | 0.772 | 0.068 | 13.275 | *** | |||

| Q9 | 0.780 | 0.069 | 13.478 | *** | |||

| Q10 | 0.835 | 0.068 | 14.827 | *** | |||

| Belief in participating in ACP | Q11 | 0.837 | 0.898 | 0.639 | |||

| Q12 | 0.756 | 0.072 | 12.853 | *** | |||

| Q13 | 0.788 | 0.073 | 13.622 | *** | |||

| Q14 | 0.826 | 0.071 | 14.572 | *** | |||

| Q15 | 0.786 | 0.072 | 13.584 | *** | |||

| Motivation to undertake ACP | Q16 | 0.767 | 0.889 | 0.533 | |||

| Q17 | 0.736 | 0.086 | 11.187 | *** | |||

| Q18 | 0.726 | 0.086 | 11.017 | *** | |||

| Q19 | 0.706 | 0.078 | 10.677 | *** | |||

| Q20 | 0.767 | 0.089 | 11.722 | *** | |||

| Q21 | 0.709 | 0.086 | 10.738 | *** | |||

| Q22 | 0.694 | 0.083 | 10.473 | *** |

- *** Stands for p < 0.001.

| Variable | Mean | Standard deviation | Attitude to ACP | Belief in participating in ACP | Motivation to undertake ACP |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Attitude to ACP | 3.400 | 0.919 | 0.782 | ||

| Belief in participating in ACP | 3.640 | 0.850 | 0.481** | 0.799 | |

| Motivation to undertake ACP | 3.427 | 0.858 | 0.389** | 0.395** | 0.730 |

- Note: The numbers in bold are the arithmetic square roots of the AVEs.

- ** Stands for p < 0.01.

5 DISCUSSION

In light of the accelerating global ageing process and the increasing emphasis on humanistic values and autonomy, addressing EOL comfort for older adults has become a crucial societal concern (Jin et al., 2022). Suburbs, as integral components of global urbanization, play a vital role in disseminating health policies and enhancing public awareness (Shi et al., 2020). However, compared with the urban population, suburban older adults characterized by less-education and lower-income still hold large difference in the concept of receiving medical treatment (Liu et al., 2013; Wang et al., 2021), posing unique challenges to the implementation of health policies (Zhong et al., 2020). Effectively addressing EOL care for this population is pivotal for successful ageing. Given that ACP readiness is an important predictor of participation in ACP (Hutchison et al., 2017; Zwakman et al., 2021), there is an urgent need for a validated tool to measure the ACP readiness among the community-dwelling older adults with chronic diseases residing in suburban counties within the Chinese context.

Results from item analysis revealed decision values surpassed 3 (p < 0.001), and the correlation tests all exceeded 0.4 (p < 0.01), meeting retention criteria for all items in the reliability analysis (Jinshan et al., 2010). The content validity results, supported by the judgement of 10 experts, indicated high I-CVI and S-CVI scores, reinforcing the appropriateness of each item as an indicator for assessing ACP readiness (Holle et al., 2017). Aligned with readiness to change modelling theory, readiness to change encompasses an individual's beliefs, attitudes, and motivations regarding the necessity for change and their capacity to bring about change (Armenakis et al., 1993). The ACPRS-C is structured by the attitude, beliefs, and motivation dimensions (Wang & Sheng, 2022). These dimensions essentially encapsulate the fundamental aspects of assessing ACP readiness. Certain scale items, such as “After expressing my care preferences, the doctor may give up treatment prematurely” and “Participating in ACP conversation is unlucky”, reflecting cultural sensitivities and educational disparities among suburban older adults (Liu et al., 2013; Wang et al., 2021).

The ACPRS-C displayed strong evidence of internal consistency and validity across multiple dimensions. High Cronbach's alpha coefficients for the entire scale and each dimension (>0.8) indicated homogeneity (Mascha & Vetter, 2018). This finding similarly to the results of Yuan and Liu (2020), who reported a Cronbach's alpha of 0.912. Additionally, the CITC for each observed variable within their respective latent variables surpassed 0.5, affirming each item was well connected with the entire concept (Ho & Lin, 2010). Furthermore, the CFA results affirmed strong structural validity, with standardized factor loadings exceeding 0.5, suggesting substantial contribution of observed variables to latent variables (Creswell, 2015). Combining reliabilities above 0.8 and AVE values exceeding 0.5 further supported the scale's convergent validity (Creswell, 2015).

Given the favourable psychometric properties of the ACPRS-C, the scale is valid and reliable for assessing ACP readiness among older adults with chronic diseases in suburban counties in China. Healthcare professionals can use it to determine the timing of ACP initiation in older adults (Hutchison et al., 2017; Zwakman et al., 2021).

6 LIMITATIONS

The present study has several limitations. First, given the sensitivity of the ACP topic, test–retest reliability and external criterion measures were not conducted in this study to avoid causing additional fear and anxiety from older adults (Hutchison et al., 2017). Instead, a Cronbach alpha test was performed on 228 participants to ascertain the acceptable internal consistency of the ACPRS-C variable. Secondly, the ACPRS-C is self-report scale, which may introduce bias or lack objectivity. Further research could employ multi-dimensional data collection methods, such as health professionals or family members evaluating older adults.

7 IMPLICATION FOR NURSING

The findings of this study provide a validated tool for assessing ACP readiness among older adults with chronic diseases in suburban China, thus aiding further research into factors influencing ACP readiness, the effectiveness of related interventions, and its impact on patient outcomes and healthcare utilization. The robustness of the ACPRS-C renders it invaluable for healthcare professionals in suburban China, enabling accurate assessment of ACP readiness. This facilitates patient-centred care through discussions about healthcare preferences, goals, and values, thereby enhancing patient–provider communication, satisfaction, and potentially improving health outcomes.

8 CONCLUSION

Based on the results of the psychometric analyses conducted, there is a clear indication that the ACPRS-C stands as a dependable tool for evaluating the readiness toward ACP in the context of older adults with chronic diseases among suburban counties in China. Its reliability and validity hold considerable significance for both research and clinical practice.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

All the authors have contributed to the design, analysis, and writing of this study. Fang Gao inolved in conception and design. Ping Lei Chui and Chong Chin Che involved in administrative support. Fang Gao, Li Xiao, and Fan Wang involved in collection and assembly of data. All authors involved in data analysis and interpretation. Fang Gao involved in manuscript writing. All authors involved in final approval of manuscript.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

The authors are especially grateful to our colleagues at fellow students at the Universiti Malaya who have provided insight and expertise that greatly assisted this study.

FUNDING INFORMATION

This research was supported by the Sichuan Provincial Cadre Healthcare Research Program (CGY2023-226).

CONFLICT OF INTEREST STATEMENT

The author(s) declare that they have no conflict of interests.

Open Research

DATA AVAILABILITY STATEMENT

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.