The quality of occupational healthcare for carpal tunnel syndrome, healthcare expenditures, and disability outcomes: A prospective observational study

Funding information: Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality, Grant/Award Number: R01HS018982; California Commission on Health and Safety and Workers’ Compensation (CHSWC); Zenith Insurance; Cedars-Sinai Medical Center; RAND Corporation; Kaiser Permanente

Abstract

Introduction/aims

In prior work, higher quality care for work-associated carpal tunnel syndrome (CTS) was associated with improved symptoms, functional status, and overall health. We sought to examine whether quality of care is associated with healthcare expenditures or disability.

Methods

Among 343 adults with workers' compensation claims for CTS, we created patient-level aggregate quality scores for underuse (not receiving highly beneficial care) and overuse (receiving care for which risks exceed benefits). We assessed whether each aggregate quality score (0%–100%, 100% = better care) was associated with healthcare expenditures (18-mo expenditures, any anticipated need for future expenditures) or disability (days on temporary disability, permanent impairment rating at 18 mo).

Results

Mean aggregate quality scores were 77.8% (standard deviation [SD] 16.5%) for underuse and 89.2% (SD 11.0%) for overuse. An underuse score of 100% was associated with higher risk-adjusted 18-mo expenditures ($3672; 95% confidence interval [CI] $324 to $7021) but not with future expenditures (−0.07 percentage points; 95% CI −0.48 to 0.34), relative to a score of 0%. An overuse score of 100% was associated with lower 18-mo expenditures (−$4549, 95% CI −$8792 to −$306) and a modestly lower likelihood of future expenditures (−0.62 percentage points, 95% CI −1.23 to −0.02). Quality of care was not associated with disability.

Discussion

Improving quality of care could increase or lower short-term healthcare expenditures, depending on how often care is currently underused or overused. Future research is needed on quality of care in varied workers' compensation contexts, as well as effective and economical strategies for improving quality.

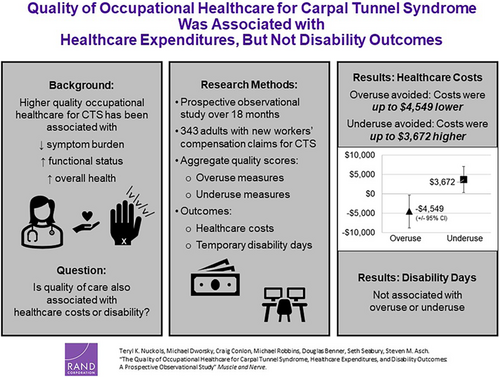

Graphical Abstract

Higher quality occupational healthcare for CTS is associated with improved symptoms, function, and health.

This study assessed whether quality was also associated with healthcare costs or disability over 18 mo among 343 adults.

Adherence to overuse measures was associated with lower costs (up to −$4549). Adherence to underuse measures was associated with higher costs (up to $3672). Quality was not associated with disability.

Improving quality could increase or lower costs, depending on baseline underuse and overuse.

1 INTRODUCTION

Carpal tunnel syndrome (CTS) is common among employed populations, is often attributed to work, and leads to substantial healthcare expenditures and sizeable disability costs.1 The quality of occupational healthcare in the United States has been called into question,2 including care for CTS.3, 4 Moreover, a large body of literature has demonstrated that quality of care is suboptimal for a wide range of conditions, including neurologic and musculoskeletal disorders.5-8 Quality of care represents “the degree to which health care services for individuals and populations increase the likelihood of desired health outcomes and are consistent with current professional knowledge.”9

In prior work, we assessed the quality of occupational healthcare for CTS and examined whether it was associated with differences in patient-reported outcomes. We used process-oriented quality measures that addressed several aspects of care: evaluation and monitoring, non-operative treatment, activity assessment and management, and the appropriateness of surgery.10, 11 In a population with new workers' compensation claims for CTS, we found that, overall, 81.6% of care adhered to recommended standards.3 Notably, patients who received higher quality care, including appropriate surgery, experienced larger improvements in symptoms, functional status, and overall health over an 18-mo follow-up period.3, 4, 12, 13

The quality of occupational healthcare for CTS has the potential to affect not only health outcomes but also workers' compensation costs. Higher quality care may influence healthcare expenditures if the care involves a more or less extensive set of clinical services or if improvements in health reduce the need for ongoing medical care over the longer term. Additionally, improvements in functional status may translate into an increased ability to work and reduced temporary and permanent disability. In a 2005 study, an intervention that promoted adherence to guidelines for musculoskeletal conditions, including CTS, reduced healthcare expenditures and disability.14

The present analysis tested prespecified hypotheses that higher quality care for CTS would be associated with lower healthcare expenditures (short-term expenditures and anticipated future expenditures) and less disability (temporary total disability and permanent disability).

2 METHODS

We adhered to the STrengthening the Reporting of OBservational studies in Epidemiology Statement in reporting this work.15 In partnership with Kaiser Permanente Northern California, we prospectively recruited adults with workers' compensation claims for CTS, reviewed medical records to evaluate adherence to quality measures, and compared healthcare expenditures and disability between patients who received higher vs. lower quality of care. Prior publications describe quality measure development, study design, overall quality of care for CTS, and associations with patient-reported outcomes.3, 12, 13, 16-18

2.1 Setting and participants

The study setting was 30 Kaiser Permanente Northern California Regional Occupational Health centers, where specialists in occupational medicine treat 45,000 individuals with workers' compensation claims annually. Kaiser Permanente contracts, on a fee-for-service basis, with numerous large and small employers, workers' compensation insurance carriers, and third-party administrators of workers' compensation claims. Most occupational healthcare is provided by in-system specialists; occasionally, the workers' compensation payer may approve and direct care to external electrodiagnostic medicine specialists and hand surgeons. Kaiser Permanente has a fully electronic medical record system as well as a comprehensive database of workers' compensation claims that includes information on employer, payer, patient characteristics and diagnoses, recommended worksite accommodations, recommended and actual work status, healthcare utilization and claims (by diagnosis), and prescriptions and pharmacy claims (by diagnosis). Copies of California workers' compensation forms, including Doctor's First Report, Progress Report, and Permanent and Stationary Report forms are also included. About 70% of patients treated by Regional Occupational Health also have general health insurance through Kaiser Permanente Northern California, which augmented the completeness of medical records.

Study participants were prospectively identified adults ages ≥18 y with newly coded diagnoses of CTS (International Classification of Diseases, Ninth Revision [ICD-9] code 354.0 or 354.1), excluding individuals who did not speak English or Spanish as well as Kaiser Permanente employees. Because several quality measures address the initial evaluation of symptoms, we did not require patients to have typical presentations or electrodiagnostic confirmation of CTS to be eligible. Kaiser Permanente case managers identified potentially eligible subjects within 1–2 workdays of a new workers' compensation claim for CTS, contacted them by mail and telephone to recruit them and obtain verbal informed consent, and then referred consenting subjects to survey researchers. For the present analysis, subjects had to complete telephone surveys at recruitment (August 2011 to March 2013) and 18 mo (May 2013 to October 2014), have clinic visits at a study site, not have acute CTS (associated with a distal radius fracture or other severe wrist injury), and be eligible for at least one quality measure. People with diabetes as the cause of CTS would not be accepted in the occupational medicine clinics or included in the study; people with diabetes as a comorbidity to CTS were included in the study. If subjects had claims for CTS in both hands, data collection focused on the self-reported dominant hand.

Institutional Human Subjects' Protections Committees at Kaiser Permanente and the RAND Corporation approved the study.

2.2 Quality of care

The primary independent variables were patient-level aggregate scores for quality of care, including an aggregate score for all measures of underuse and an aggregate score for all measures of overuse. Underuse was defined as omitting necessary care, meaning care for which benefits greatly exceeded risks.5, 19 Overuse was defined as providing inappropriate care, meaning care for which risks exceeded benefits.5, 19

To create these aggregate quality scores, we used 45 process-oriented measures (Appendix Table 1).12, 16, 17, 20 Each measure had detailed criteria for determining when recommended care should be provided to an individual patient (the measure denominator) and criteria for assessing whether care adhered to recommendations (the measure numerator). Ten measures addressed the initial evaluation and monitoring, 11 addressed non-operative treatment, 11 addressed care related to activity assessment and management, and 13 addressed the appropriateness of surgery. The present analysis assumed that all electrodiagnostic tests were high quality. Quality measures related to how electrodiagnostic testing is performed were studied in recent separate analyses.4, 21

| Measure title | Type |

|---|---|

| Evaluation and monitoring (10 measures) | |

| New symptoms characteristic of CTS require detailed assessment | Underuse |

| New symptoms characteristic of CTS should lead to suspicion | Underuse |

| New hand or forearm pain requires evaluation for "red flags" | Underuse |

| New symptoms inconsistent with CTS require evaluation | Underuse |

| New CTS diagnosis requires assessment of medical risk factors | Underuse |

| New suspicion of CTS requires specific physical examination | Underuse |

| New suspicion of CTS requires evaluation for excessive weight | Underuse |

| Imaging should be used selectively for suspected CTS | Underuse |

| Symptoms should be monitored after new diagnosis of CTS | Underuse |

| Preoperative electrodiagnostic testing for work-associated CTS | Underuse |

| Non-operative treatment (11 measures) | |

| Splints should be placed in neutral position | Underuse |

| An attempt at splinting should last at least six weeks | Underuse |

| NSAIDs should not be used for CTS | Overuse |

| Muscle relaxants should not be used for CTS | Overuse |

| Opioids should not be used for CTS | Overuse |

| Diuretics should not be used for CTS | Overuse |

| Steroid treatment requires discussion of risks | Underuse |

| Discuss benefits of surgery when offering steroids to patients with severe CTS | Underuse |

| Steroids for work-associated symptoms require follow-up | Underuse |

| Limit steroid injections to four | Overuse |

| Laser therapy should not be used for CTS | Overuse |

| Activity assessment and management (11 measures) | |

| New CTS diagnosis requires detailed occupational history | Underuse |

| New CTS diagnosis requires assessment of occupational factors | Underuse |

| New CTS diagnosis requires assessment of non-occupational factors | Underuse |

| Exacerbating activities should be identified when symptoms limit functioning | Underuse |

| Rationale for work-association should be documented | Underuse |

| Patients newly diagnosed with CTS should be educated about the condition | Underuse |

| Exposures to vibration, force, and repetition should be minimized | Underuse |

| Work-associated CTS symptoms require prompt follow-up | Underuse |

| Work status should be monitored when CTS appears work-associated | Underuse |

| Return to work after CTS-related disability requires follow-up assessment that includes functional limitations | Underuse |

| Prolonged CTS-related disability should trigger evaluation | Underuse |

| Surgical appropriateness (13 measures) | |

| Compelling indications for surgery when CTS is mild | Underuse |

| Compelling indications for surgery when CTS is moderate (2 measures) | Underuse |

| Compelling indications for surgery when CTS is severe (3 measures) | Underuse |

| Avoidance of carpal tunnel surgery during pregnancy | Overuse |

| Compelling contra-indications for surgery when CTS is mild (2 measures) | Overuse |

| Compelling contra-indications for surgery when CTS is moderate (4 measures) | Overuse |

Each aggregate quality score ranged from 0% to 100%, where higher scores reflected better care. For underuse quality measures, 100% adherence means providing all necessary care across 32 measures. For overuse measures, 100% adherence means avoiding all inappropriate care across 13 measures. When aggregating performance across multiple measures to create a quality score, there were three steps. First, we ascertained eligibility for and adherence to individual measures, creating measure-level scores for each patient (when eligible for a measure, 1 = care adhered to the measure, 0 = care did not adhere). Second, for each patient and measure, we standardized the score by subtracting the measure's mean adherence rate in the population from the individual patient's score; this accounted for variations in measure eligibility across patients and in adherence across measures. Third, we averaged the standardized scores across all measures for which the patient was eligible.

For one set of secondary analyses, we used an aggregate subscore for the underuse of activity assessment and management (11 measures) because this subscore was associated with differences in functional status in our prior work.

2.3 Data collection and outcome measures

2.3.1 Data sources

Kaiser Permanente provided data from internal administrative databases to determine study eligibility and calculate healthcare expenditures during the study period. Professional survey researchers conducted telephone interviews with study subjects at recruitment and 18 mo, yielding data on covariates. To assess quality of care and obtain additional covariates, three specially trained professional abstractors at Kaiser Permanente manually extracted variables related to eligibility and adherence for each quality measure by reviewing electronic medical records from CTS-related visits from 3 mo before to 12 mo after recruitment. An occupational medicine physician at Kaiser Permanente manually reviewed electronic medical records and associated workers' compensation records to extract variables related to temporary disability, permanent disability, and anticipated future healthcare expenditures.

2.4 Healthcare expenditures

We examined two cost measures: (1) short-term expenditures and (2) the anticipated need for future healthcare expenditures.

Short-term expenditures reflected the U.S. dollars spent on all workers' compensation care related to conditions of the upper extremity, shoulder, or neck from recruitment through 18 mo. To calculate short-term expenditures, we summed billed amounts for all physician visits, medications, therapy visits, diagnostic tests, and surgery related to conditions of the upper extremity, shoulder, or neck. Amounts spent on individual services were consistent with the California Official Medical Fee Schedule for workers' compensation.22

Anticipated future healthcare expenditures reflected whether there was a need for ongoing medical care for CTS after closure of the workers' compensation claim; this was a binary variable (yes, no). To determine anticipated expenditures, an occupational medicine physician extracted information from Permanent and Stationary Reports on whether treating physicians thought that insurers should allocate reserves for future medical care after closure of the workers' compensation claim. Treating physicians at study clinics create Permanent and Stationary reports when patients have ongoing symptoms that are unlikely to improve further. These reports become part of the electronic medical record. If a patient had no report, the occupational medicine physician reviewed the medical record to confirm that future care was not needed.

2.4.1 Disability

We examined two disability outcomes: (1) days on temporary total disability; and (2) permanent impairment rating.

Days on temporary total disability extended from recruitment to 18 mo (range 0 to 548 days). To determine days on temporary total disability, we used data that abstractors obtained from the electronic medical record to classify each patient as not working due to the injury, working on modified duty, or working on full duty for each day in the 18-mo follow-up period and then we summed the days that the patient was not working. Treating physicians at study clinics document the patient's actual work status at each occupational health visit, as well as recommendations to remain off work, be placed on modified duty during a specified period, or return to work at full capacity on a specified date. We used the actual work status or, if that was missing for a particular date, the recommended work status.

The permanent impairment rating was assessed at closure of the workers' compensation claim (range 0% to 100%; 100% = total permanent disability). The impairment rating was based on American Medical Association Guides to the Evaluation of Permanent Impairment, 5th Edition,23 as per California regulations. To determine the impairment rating, the occupational medicine physician reviewed Permanent and Stationary Reports. If there was no report, he reviewed the electronic medical record to determine whether the patient had been released from care due to improvement (in which case, we assumed the rating was 0%) or lost to follow-up (in which case, we considered the rating missing).

2.4.2 Covariates

Variables based on surveys included race/ethnicity, gender, age, baseline annual income, monthly earnings prior to the workers' compensation claim, baseline work status, history of prior workers' compensation claims for hand/wrist conditions, smoking, medical risk factors for CTS (thyroid disease, kidney disease, arthritis, or obesity), and baseline scores on the Boston Carpal Tunnel Questionnaire and the Short Form Health Survey, version 2 (SF-12v2).24-28 Surveys also included items related to five job factors: (1) patients' perceptions of the safety climate at work at baseline (scale 1–4, 4 = best); (2) whether, by 18 mo, the employer made any changes to the job activities to reduce symptoms (yes, no); (3) whether, by 18 mo, the worker was able to change job activities for >6 wk to reduce symptoms (yes, no); (4) whether, at 18 mo, the job required use of force or vibrating power tools (yes, no); and (5) whether, by 18 mo, an expert had evaluated job tasks and recommended changes to reduce symptoms (yes vs. no).

Variables based on medical record data included medical risk factors for CTS (thyroid disease, kidney disease, arthritis, or obesity); and electrodiagnostic test findings, timing of presentation (days between diagnosis and first visit to occupational health for CTS symptoms), locations of symptoms (used to score Katz hand diagram),29 symptom timing, neurological signs (any thenar atrophy, thenar weakness, or loss of sensibility in digits 1–3), and electrodiagnostic test results (any positive test or not). Symptom timing (constant, intermittent, unclear/missing) and clinical probability of CTS (classic/probable Katz Diagram vs. not classic/probable) were based on the most severe findings from medical record and survey data.

2.5 Analysis

2.5.1 Main analysis

We performed multivariate regression analyses that assessed associations between healthcare expenditures and disability (dependent variables) with aggregate quality scores for underuse and overuse (independent variables). To present results in a format that was easy to understand, we compared predicted outcomes between hypothetical patients who had perfect quality scores (100% adherence) and hypothetical patients who had the worst possible scores (0% adherence). Statistical testing was based on the strength of associations, not the values of the independent variables compared.

Model specifications matched the type of dependent variable: we used Poisson regression for skewed non-negative continuous outcomes (temporary disability days, healthcare expenditures); linear regression for non-skewed continuous outcomes (impairment ratings); and logistic regression for binary outcomes (anticipated future expenditures). Study sample sizes and power calculations were originally based on patient-reported outcomes, reported previously.12

Models controlled for age category, gender, race, Hispanic ethnicity, baseline scores on the Boston Carpal Tunnel Questionnaire and SF-12v2, the timing of diagnosis relative to study recruitment, smoking, clinical risk factors for CTS, presence of neurological signs, prior workers' compensation claim for CTS, log of monthly income at baseline, and job factors.

2.6 Secondary analyses

We conducted two secondary analyses. First, we examined associations between the quality score for activity assessment and management and outcomes. Second, we restricted the sample to subjects with classic/probable symptoms and positive electrodiagnostic tests, as per a published consensus definition of CTS.29, 30 We did not directly examine relationships between the underuse or overuse of surgery and study outcomes because too few patients were eligible for or had care that deviated from the surgical appropriateness measures.

3 RESULTS

3.1 Participants

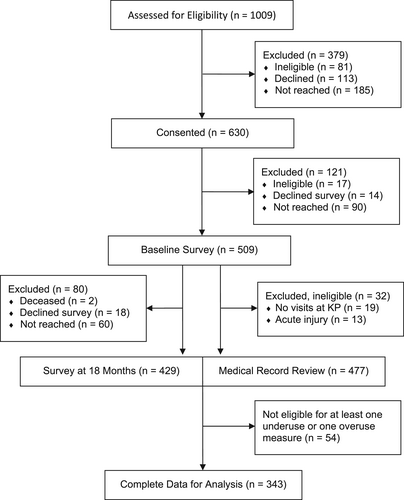

Of 1009 individuals with newly coded CTS, 630 consented (67.9% of those eligible), 509 completed baseline surveys (83.0% of those consented and eligible), 429 completed follow-up surveys (84.3% of those who completed the baseline survey), 397 had complete survey and medical record data, and 343 were eligible for one or more regression analyses (Figure 1). Table 1 includes characteristics of study participants.

| Age, mean (SD)a | 48 (10.2) | |

|---|---|---|

| Gender, female, N (%)a | 261 (76.1) | |

| Race, white, N (%)b | 171 (49.9) | |

| Hispanic ethnicity, N (%)b | 81 (23.6) | |

| Annual personal income during 12 mo before claim, N (%)a | ||

| ≤$18,000 | 67 (21.6) | |

| >$18,000–$36,000 | 79 (23.1) | |

| >$36,000–$54,000 | 68 (20.6) | |

| >$54,000–$72,000 | 79 (21.0) | |

| >$72,000 | 50 (13.8) | |

| Medical risk factors for CTS (overweight, thyroid disorders, kidney disorders, or arthritis), N (%)a,b | 304 (88.6) | |

| Overweight (BMI > 25) or obese (BMI > 30)a | 276 (80.5) | |

| History of thyroid disorderb | 41 (12.0) | |

| History of kidney disorderb | 12 (3.5) | |

| History of arthritisb | 149 (43.4) | |

| Duration of symptoms, N (%)a | ||

| < 6 mo | 91 (26.5) | |

| 6–24 mo | 147 (42.9) | |

| > 24 mo | 101 (29.5) | |

| Clinical probability of CTS (symptom pattern on Katz diagram), N (%)a,c | ||

| Classic or probable CTS | 180 (52.4) | |

| Possible CTS | 140 (40.8) | |

| CTS unlikely | 23 (6.7) | |

| Constant symptoms, N (%)a,c | 213 (62.1) | |

| Neurological signs, N (%)c | 160 (46.7) | |

| Thenar weakness | 60(17.5) | |

| Thenar atrophy | 41 (12.0) | |

| Loss of sensibility in digits 1, 2, or 3 | 165 (34.6) | |

| Result of electrodiagnostic testing for CTS, N (%)c | ||

| One or more positive tests | 255 (74.3) | |

| All tests indeterminate | 11 (3.2) | |

| One or more tests negative and none positive | 39 (11.4) | |

| No tests done | 38 (11.1) | |

| Bilateral workers' compensation claims for CTS, N (%)a | 184 (53.6) | |

| Before CTS, job satisfaction (scale 1–4, 1 = best), mean (SD)a | 3.5 (0.7) | |

| At baseline, safety climate at work (scale 1–4, 1 = best), mean (SD)a | 2.1 (0.8) | |

| Previous claim in upper extremity, N (%)a | 54 (15.7) | |

| Attorney involved in claim, N (%)b | 47 (13.7) | |

| Received care for CTS prior to care at KPNC, N (%)a | 90 (26.2) | |

| Received concurrent care outside KPNC, N (%)b | 130 (37.9) | |

| By 18 mo, expert had evaluated job tasks and recommended changes, N (%)b | 148 (43.5) | |

| By 18 mo, employer had made changes to minimize exposures that exacerbate the patient's symptoms, N (%)b | 138 (40.2) | |

| At 18 mo, use of force or vibrating power tools, N (%)b | 168 (49.0) | |

- Abbreviations: BMI, body mass index; CTS, carpal tunnel syndrome; KPNC, Kaiser Permanente Northern California Regional Occupational Health.

- a Based on baseline survey. For personal income, includes imputed values.

- b Based on follow-up survey.

- c Based on medical record review.

3.1.1 Quality of care

The mean aggregate quality score for underuse was 77.8% (standard deviation [SD] 16.5%), indicating that recommended care was underused 22.2% of the time (N = 343). The mean aggregate quality score for overuse was 89.2% (SD 11.0%), indicating that care was overused 10.8% of the time.

For the underuse of activity assessment and management, the mean aggregate quality score was 81.4% (SD 20.4%).

Underuse of surgery affected 12 of 100 patients (12%) for whom surgery was necessary. Overuse of surgery affected 4 of 75 patients (5.3%) for whom surgery was inappropriate. (Surgery was of intermediate appropriateness for the remaining subjects.)

3.1.2 Healthcare expenditures

Among patients with complete medical record and survey data, mean short-term healthcare expenditures were $7218 (SD $6070) during the 18-mo follow-up period (N = 397, 3 patients had missing data). Half of subjects had anticipated future healthcare expenditures (151/305, 49.5%, 92 patients had missing data).

3.1.3 Disability

The mean number of days on temporary disability was 19.7 (SD 36.7; N = 397 including patients with zero days of disability). The mean permanent impairment rating was 1.3% (SD 3.3; N = 300 including patients with ratings of zero, 97 had missing data).

3.2 Main results

3.2.1 Healthcare expenditures

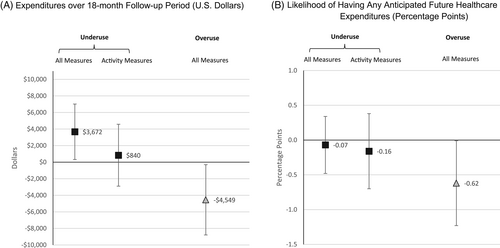

Having higher aggregate quality scores for underuse (receiving more necessary care) was associated with greater short-term expenditures, but not with differences in anticipated future expenditures. Hypothetical patients with aggregate underuse scores of 100% had higher risk-adjusted expenditures over 18 mo than patients with scores of 0% (difference of $3672; 95% confidence interval [CI] $324 to $7021, Figure 2A). The rate of anticipated future healthcare expenditures was similar between those having underuse scores of 100% vs. 0% (difference of −0.07 percentage points; 95% CI −0.48 to 0.34, Figure 2B).

For overuse, aggregate quality scores of 100% (i.e., avoiding all inappropriate care) were associated with lower short-term expenditures (difference of −$4549, 95% CI −$8792 to −$306) and a lower rate of having anticipated future healthcare expenditures (difference of −0.62 percentage points, 95% CI −1.23 to −0.02) than scores of 0%.

3.2.2 Disability

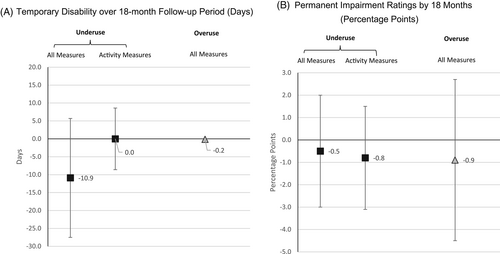

Differences between hypothetical patients with aggregate quality scores of 100% vs. 0% were not significant for underuse measures (−10.9 temporary disability days; 95% CI −27.5 to 5.7, Figure 3A; −0.5 percentage points on permanent impairment ratings, 95% CI −3.0 to 2.0, Figure 3B) or overuse measures (−0.15 temporary disability days; 95% CI −0.01 to 0.29; −0.9 percentage points of permanent impairment ratings, 95% CI −4.5 to 2.7).

3.3 Secondary analyses

3.3.1 Underuse of activity assessment and management

Differences between aggregate quality scores of 100% vs. 0% were not significant for short-term expenditures ($840, 95% CI −$2899 to $4579, Figure 2A), anticipated future expenditures (−0.16 percentage points, 95% CI −0.70 to 0.38, Figure 2B), temporary disability (0.0 days, 95% CI −8.6 to 8.6, Figure 3A), or permanent impairment ratings (−0.8 percentage points, 95% CI −3.1 to 1.5, Figure 3B).

3.3.2 Consensus definition of CTS

Results did not change after we excluded patients who lacked classic/probable symptoms or positive electrodiagnostic tests, but these analyses had smaller sample sizes.

4 DISCUSSION

This analysis had two main findings. First, the quality of occupational healthcare for carpal tunnel syndrome was associated with healthcare expenditures, with the direction of the relationship depending on whether the quality measures addressed underuse or overuse. Specifically, providing all necessary care recommended by 32 underuse measures was associated with $3672-higher short-term healthcare expenditures per patient than providing none of the necessary care. This is a sizeable difference, given the mean per-patient expenditure was $7218. Conversely, avoiding care proscribed by 13 overuse measures was associated with $4549-lower short-term expenditures and a lower likelihood of having any anticipated future expenditures after closure of the workers' compensation claim. Second, we did not detect associations between disability and quality of care, including for underuse measures related to the assessment and management of patient's activities.

The association between adherence to underuse measures and short-term expenditures is most likely explained by patients receiving surgery, even though we did not assess this relationship directly. The aggregate quality score for underuse includes a measure addressing surgery and a sizeable minority of patients were eligible for it (100/343 patients). Surgery is the most expensive service included in workers' compensation claims for CTS. The other underuse measures, aside from surgery, are less likely to directly increase expenditures because adherence seldom requires additional visits, medications, tests, procedures, or equipment. These measures largely address whether physicians perform existing tasks correctly, such as how they evaluate suspected CTS, prescribe splints, counsel patients, and assess and manage patients' activities (see Appendix Table 1).

Moreover, adherence to non-surgical underuse measures, particularly measures related to initial evaluation and conservative management, could have created cost offsets that attenuated the increase in healthcare expenditures (i.e., reduced it from what it might have been). Previously, we found that better quality care was associated with larger improvements in CTS symptoms.12 Symptom severity is the most important reason to undergo surgery for CTS. Thus, providing better care early on may reduce the eventual need for surgery as well as its associated expenditures.

Changes in the utilization of surgery also likely explain why avoiding overuse was associated with lower healthcare expenditures. The aggregate quality score for overuse includes inappropriate surgery and 75 of 343 of patients were eligible for this measure. Adhering to this measure averts the short-term expenditures associated with carpal tunnel release itself. Additionally, because inappropriate operations can be associated costly complications, there is a second mechanism by which avoiding overuse can lower healthcare expenditures. The occasionally long-lasting nature of operative complications could explain why we found that less overuse was linked to both lower short-term expenditures and less of a need for anticipated future healthcare expenditures, although changes in the latter were modest.

The implications of our findings for future efforts to improve quality of care depend critically on baseline rates of underuse and overuse. In California and at least 38 other states, workers' compensation payers limit the overuse of care by employing medical treatment guidelines in utilization review. Thus, there are fewer opportunities to improve performance on overuse measures, including to reduce the inappropriate utilization of surgery. In our study population, very few patients underwent inappropriate surgery (4 of 75). However, for the underuse of necessary care, systematic efforts to monitor or improve care are rare in workers' compensation settings. Based on our work, where the underuse of necessary care is common, systematic efforts to improve care may improve patient-reported symptoms, functional status, and overall health—but also meaningfully increase healthcare expenditures.12

In addition to healthcare expenditures, workers' compensation payers and policymakers are also concerned about costs related to disability. Prior studies suggest that higher quality care can be associated with reduced disability. In an earlier study, adherence to guidelines for musculoskeletal conditions was associated with declines in both temporary and permanent disability.14 In another study, periods of temporary disability were shorter when the diagnosing provider and operating surgeon treated higher volumes of patients with workers' compensation claims for CTS.31 Volume is widely viewed as an indirect measure of quality of care because it often associated with greater use of recommended care processes and better outcomes.32 We did not detect an association between quality of care and temporary disability, possibly because Kaiser Permanente had already implemented initiatives to have occupational medicine physicians recommend modified duty over temporary disability when possible.

This analysis has several limitations. Because this is an observational study, we cannot assert that observed relationships involve causation. For example, physicians may have responded to patients with more severe CTS symptoms by providing both higher quality care (eg, performing more thorough physical examinations) and larger quantities of care (eg, scheduling more frequent follow-up visits and making more referrals for testing and surgery), which would create the appearance of an association between performance on the aggregate underuse score and healthcare expenditures. Associations between quality and economic outcomes can be challenging to detect because, at a population level, quality measures can exhibit a ceiling effect and, in this population, quality was relatively high, and variation in quality was modest. These conditions may not generalize to other study settings. We included patients who were ultimately found not to have CTS because several measures address the diagnostic evaluation; nonetheless, a more accurate diagnosis also benefits patients without CTS. We may have had a reduced ability to detect an association with the duration of temporary disability because we based this on actual time off work due to CTS, including physician-recommended time off (generally, to undergo surgery) plus time off that was not under physician control (eg, related to employer and/or worker factors).13 Additionally, our study sample size was limited relative to the rarity of some rare outcomes (eg, permanent disability) so those analyses may have been underpowered. Finally, the present analysis omitted several measures addressing details of how electrodiagnostic tests should be performed, and assumed all tests were high quality. However, in prior work, we did not find that performance on those measures was associated with economic outcomes.21

In conclusion, the quality of occupational healthcare for CTS is associated with sizeable and statistically significant differences in healthcare expenditures. Due to deficiencies in the current quality of care and significant associations between quality and health outcomes including symptoms and functional status, workers' compensation policymakers and health systems that treat large numbers of patients with CTS may seek to examine quality of care more systematically and to implement interventions designed to improve the quality of occupational healthcare. In light of our current findings, entities implementing such interventions should anticipate possible changes in healthcare expenditures as well as health outcomes. Future research is needed on quality of care for diverse conditions in varied workers' compensation contexts, as well as effective and economical strategies for improving quality of care.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

A partnership between Kaiser Permanente Northern California Regional Occupational Health and the RAND Corporation made this study possible. We are indebted to individuals at Kaiser Permanente Northern California Department of Research (Rick Riordan, Karen Forsen, Monica Highbaugh, Barbara Anglin, Sandy Bauska); Kaiser Permanente Regional Occupational Health (Gene Nardi, Connie Chiulli, Annie Pang, and the case managers); DataStat, Inc., Ann Arbor, MI; the RAND Corporation (Lance Tan, Scot Hickey, Barbara Levitan, Carol Roth, Peggy Chen, Julie Lai, Rachana Seelam); and Cedars-Sinai Medical Center (Margaret Kelley, Andrew Henreid). This study would not have been possible without the support of Christine Baker (previous Director, Department of Industrial Relations), present and former Commissioners for the California Commission on Health and Safety and Workers' Compensation, and Stanley Zax (former Chairman/President/CEO of Zenith Insurance). Early stages in the project were informed by input from many individuals, as acknowledged in prior publications.

CONFLICTS OF INTEREST

Dr. Nuckols has previously received research funding from the American Association of Neuromuscular and Electrodiagnostic Medicine as well as iCare New South Wales, a public financial enterprise that delivers insurance and care to individuals in New South Wales Australia. Dr. Benner is employed by EK Health Inc. and is affiliated with Macy's Inc. and Marriott International. The remaining authors have no conflicts of interest to disclose.

List of Abbreviations

-

- CTS

-

- carpal tunnel syndrome

-

- ICD-9

-

- International Classification of Diseases, Ninth Revision

-

- SF-12v2

-

- Short Form Health Survey, version 2

-

- SD

-

- standard deviation

-

- 95% CI

-

- 95% confidence interval

ETHICS STATEMENT

We confirm that we have read the Journal's position on issues involved in ethical publication and affirm that this report is consistent with those guidelines.

Open Research

DATA AVAILABILITY STATEMENT

Data subject to third party restrictions