Heightened facial muscle reactivity in preadolescent girls with pathological anxiety

Senior authors Lisa E. Williams and Ned H. Kalin have contributed equally to this work.

Abstract

Objectives

Anticipatory anxiety and heightened responses to uncertainty are central features of anxiety disorders (ADs) that contribute to clinical impairment. Anxiety symptoms typically emerge during childhood, and even subthreshold-AD symptoms are associated with distress and risk for future psychopathology. This study compared facial emotional response to threat and uncertainty between preadolescent girls with ADs, girls with subthreshold-AD symptoms, and controls.

Methods

Facial emotional responding was characterized in preadolescent girls (age 8–11) with a range of anxiety symptoms: no/low anxiety (controls, n = 41), subthreshold-AD (n = 73), and DSM-5 diagnoses of separation, social, and/or generalized ADs (n = 45). A threat anticipation paradigm examined how image valence (negative/neutral) and image anticipation (uncertain/certain timing) impacted activity of the corrugator supercilii, a forehead muscle implicated in the “frown” response that is modulated by emotional stimuli (negative > neutral). Corrugator magnitude and corrugator timecourse were compared between groups.

Results

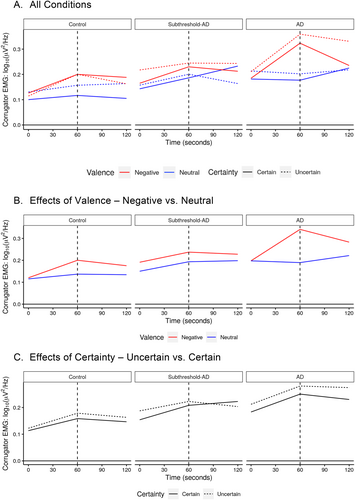

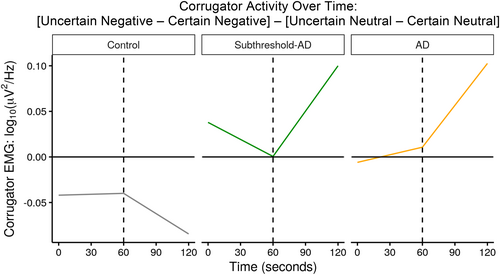

Findings demonstrate greater corrugator activity during anticipation and viewing of negative stimuli, as well as increased corrugator reactivity in subthreshold-AD and AD girls. Timecourse analyses of negative versus neutral stimuli revealed that AD and subthreshold-AD girls had greater uncertainty-related increases in corrugator activity compared to controls.

Conclusion

Results extend the physiological characterization of childhood pathological anxiety, highlighting the impact of subthreshold-AD symptoms.

1 INTRODUCTION

Anxiety disorders (ADs) commonly emerge during childhood, and it is estimated that up to 20% of youth suffer from ADs (Costello et al., 2005). ADs are characterized by persistent and excessive worries, leading to physiological and cognitive symptoms that result in functional impairments in social, academic, and professional domains (Connolly et al., 2007). Young girls are at particular risk as there is an increase in the prevalence of anxiety and depressive disorders in girls compared to boys after puberty (Angold et al., 1998; Wade et al., 2002; Wesselhoeft et al., 2015). While studies characterizing the pathophysiological features of children and adolescents with ADs have been valuable in advancing diagnostic and treatment approaches, few studies have focused on examining children with subthreshold levels of anxiety symptoms. While these children do not meet full criteria for a DSM-5 AD diagnosis, their anxiety is associated with negative impacts on their daily living and confer risk for future stress-related psychology such as anxiety, depression, and co-morbid substance abuse (Clauss & Blackford, 2012; Essex et al., 2010). In the current study, we were particularly interested in characterizing potentially altered physiological responses to threat and uncertainty in girls with subthreshold-AD symptoms. In addition to exploring differences between subthreshold-AD girls and controls, we also examined the extent to which subthreshold-AD girls are similar to and different from girls with separation, social and generalized ADs. These data will allow for a better understanding of the range of anxiety symptoms as they contribute to levels of distress and disability, as well as to the risk for the later development of psychopathology.

Individuals with ADs have been found to be particularly sensitive to conditions of uncertainty, exhibiting distress and difficulty functioning in ambiguous situations (Comer et al., 2009; McEvoy & Mahoney, 2012). Functional brain imaging (Grupe & Nitschke, 2013; Sarinopoulos et al., 2010; Williams et al., 2014) and physiological (Grillon, 2008; Grillon et al., 2004; Nelson & Shankman, 2011) data confirm increased reactivity to anticipation and uncertainty in relation to a potentially negative event in AD individuals. Despite the high prevalence of ADs during childhood, relatively few studies have investigated pathophysiological responses to uncertainty and prolonged anticipation in children with ADs. Therefore, we sought to understand whether differences in the behavioral and physiological responses to uncertain anticipation are present not only in girls with an AD diagnosis but also in girls with subthreshold-AD symptoms.

Studying the physiological correlates of emotion processing is highly relevant for studies of anxiety as ADs are commonly associated with physiological symptoms (e.g., racing heart, sweaty palms, increased muscular tension), and laboratory studies examining heart rate, eyeblink startle, and the skin conductance response have demonstrated increased and prolonged physiological responding in AD individuals (Campbell et al., 2013; Eckman & Shean, 1997; Grillon, 2002; Grillon et al., 2004; Lader & Wing, 1964). In the current study, we used facial electromyography (EMG) to quantify responses of the corrugator supercilii muscle during both the anticipation and response to negative images. We also examined corrugator responses over time to the repeated presentations of these stimuli to characterize prolonged exposure to the anticipation and viewing of negative images.

Facial EMG responses related to emotion processing in anxiety are an interesting target because subtle variations in facial expressions are a crucial component of emotion expression and recognition. Understanding corrugator is particularly relevant for studies of anxiety as it is involved in the frown response and exhibits increased activity when individuals experience negative affect (Cacioppo et al., 1986; Heller et al., 2014; Lang et al., 1993; Larsen et al., 2003). By examining corrugator magnitude during the anticipation and viewing of negative images, as well as sustained responses to the repeated exposure to these stimuli under conditions of uncertainty, we sought to characterize anxiety-related differences in facial muscular responses as an objective measure of emotional processing. We hypothesized that elevated levels of pathological anxiety in both AD and subthreshold-AD girls would be associated with increased corrugator magnitude in response to negatively valenced stimuli, which may be further enhanced by conditions of uncertainty. We predicted there would be significant differences between AD and control girls, and that subthreshold-AD girls would exhibit physiological responses that were intermediate between AD girls and control girls. Lastly, because anxiety is characterized by prolonged worry and physiological activation, we also predicted that these effects would be apparent in girls with pathological anxiety when examining sustained responses over time.

2 MATERIALS & METHODS:

2.1 Participants

Data were collected as part of a longitudinal study examining risk factors for AD development in preadolescent girls that includes repeated assessments of clinical, multimodal brain imaging, behavioral, and physiological measures over a 3-year period. Preadolescent girls (sex determined by parent report), ages 9–11 years old, were recruited from the Madison community. Study procedures were approved by the University of Wisconsin–Madison Institutional Review Board, and informed consent from parents and assent from children were acquired. Study data was managed using REDCap (Research Electronic Data Capture) tools hosted at the University of Wisconsin-Madison, School of Medicine and Public Health, a secure, web-based application designed to support data capture for research studies (Harris et al., 2009, 2019). Here we present EMG data collected during the first year of study participation.

Prior to enrollment, child participants and their parent or guardian completed online screening forms that included the parent and child Screen for Child Anxiety Related Disorders (SCARED) scale (Birmaher et al., 1999) and MRI eligibility questions. Participants were considered eligible for the AD and subthreshold-AD groups if they had a parent or child SCARED total score >12 at two screening assessments separated by about 4 weeks (average of 30 days between screenings); potential control girls had both parent and child SCARED scores ≤10 at study screening. MRI-eligible girls (e.g., no metal in the body, no claustrophobia) meeting these SCARED criteria were eligible for an initial study visit. Eligible participants enrolled in the study were administered the Kiddie Schedule for Affective Disorders and Schizophrenia (KSADS) semi-structured interview (Birmaher et al., 2009) and the Clinical Global Impression (CGI) scale (Busner & Targum, 2007) by a trained study team member with child clinical experience. Extended CGI anchors specific to anxiety were developed for this study and used to assign a CGI-Anxiety (CGI-A) score that is specific to anxiety (details in Supporting Information S1). All diagnoses and CGI-A scores were reviewed and approved by a senior psychiatrist (Dr. Ned Kalin and collaborator Dr. Daniel Pine, Chief of the Section on Development and Affective Neuroscience, National Institute of Mental Health). Additional information about interview and diagnostic details can be found in the Supporting Information S1.

Based on these measures, girls were categorized into one of three diagnostic groups using the following criteria: Control–no past or current KSADS diagnoses, CGI-A = 1; subthreshold-AD–subsyndromal but persistent levels of symptoms associated with generalized, separation, and/or social anxiety but did not meet DSM-5 criteria for these disorders, CGI-A = 2 or 3; and AD–current KSADS diagnosis of either separation, social, and/or generalized ADs, CGI-A 4+. A small number of subthreshold-AD girls group met criteria for specific phobia (n = 4) or ADHD (n = 2). We elected to study girls with any combination of separation, social and/or generalized AD diagnoses for the AD group due to the fact that anxiety symptoms are heterogenous during childhood and this triad of disorders is highly comorbid with one another (Kendall et al., 2010; Leyfer et al., 2013). This approach is similar to large-scale treatment trials of youth anxiety (Walkup et al., 2001, 2008), and we believe girls with this clinical phenotype are reflective of girls with pathological anxiety in the community and clinic. Children in the anxiety groups could have a comorbid diagnosis of ADHD if anxiety was the primary source of dysfunction/distress. Participants with symptoms or diagnoses of depression, post-traumatic stress disorder, obsessive compulsive disorder, psychotic disorders or autism spectrum disorders were excluded. All participants were treatment naïve (no past psychological treatment or psychiatric medications) and not treatment seeking.

Data was collected from 48 AD girls, 83 subthreshold-AD girls, and 47 Control girls. However, 3 AD, 10 subthreshold-AD, and 6 control participants were excluded from the final analysis due to technical issues associated with invalid EMG signal quality, incomplete session data, and/or excessive movement artifacts. The final sample included 41 Control girls, 73 subthreshold-AD girls, and 45 AD girls (Table 1). The Childhood Opportunity Index (COI)–a census-derived composite metric of neighborhood-level education, health and environment, and socioeconomic conditions that relates to several health outcomes (Acevedo-Garcia et al., 2017, 2020) was available for n = 127 participants (28 Controls, 62 subthreshold-AD, 37 AD).

| Anxiety disorder | Subthreshold anxiety disorder | Control | Statistic: 3-Group pairwise | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Count | (n = 45) | (n = 73) | (n = 41) | - |

| Age, years, mean (±SD) | 10.55 (0.77) | 10.43 (0.84) | 10.4 (0.85) | All t < 1 |

| All p > 0.40 | ||||

| Race, n (%) | ||||

| White | 37 (82.22) | 61 (83.56) | 35 (85.37) | - |

| Black or African American | 1 (2.22) | 2 (2.74) | 1 (2.44) | - |

| Asian | - | - | 1 (2.44) | - |

| Native American or Alaskan Native | - | 2 (2.74) | - | - |

| Native Hawaiian or other Pacific Island | - | - | - | - |

| More than one | 7 (15.56) | 7 (9.59) | 3 (7.32) | - |

| Unknown | - | 1 (1.37) | 1 (2.44) | - |

| Ethnicity, n (%) | ||||

| Hispanic or Latino | 1 (2.22) | 4 (5.48) | 3 (7.32) | - |

| Child Opportunity Index (COI)–nationally z-scored composite score, mean (±SD) | 0.03 (0.02) | 0.03 (0.02) | 0.04 (0.02) | All t < 1.10 |

| All p > 0.0.23 | ||||

| CGI-A severity, mean (±SD) | 4.18 (0.49) | 2.44 (0.5) | 1 (0) | AD > Sub-AD > Control |

| All t > 10.00 | ||||

| All p < 0.001 | ||||

| SCARED, mean (±SD) | ||||

| Parent report | 31.18 (10.86) | 19.48 (9.32) | 2.9 (2.76) | AD > Sub-AD > Control |

| All t > 7.00 | ||||

| All p < 0.001 | ||||

| Child report | 33.91 (13.64) | 23.96 (9.94) | 6.97 (6.04) | AD > Sub-AD > Control |

| All t > 5.01 | ||||

| All p < 0.001 | ||||

| Diagnosis, n (%) | ||||

| Generalized anxiety disorder | 18 (40) | - | - | - |

| Separation anxiety disorder | 23 (51.11) | - | - | - |

| Social anxiety disorder | 21 (46.67) | - | - | - |

| Anxiety disorder not otherwise specified | 4 (8.89) | - | - | - |

| Specific phobia | 4 (8.89) | 4 (5.48) | - | - |

| Attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder | 2 (4.44) | 2 (2.74) | - | - |

| Oppositional defiant disorder | 1 (2.22) | - | - | - |

- Note: Statistics refer to pairwise group comparisons (AD vs. Control, Subthreshold-AD vs. Control, AD vs. Risk).

- Abbreviations: CGI-A Severity, Clinical Global Impressions Anxiety Scale Severity; COI, Child Opportunity Index; SCARED, Screen for Child Anxiety Related Disorders.

2.2 Task structure

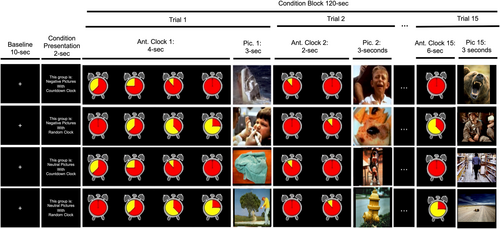

Participants completed an emotional anticipation and reactivity paradigm twice, first during an MRI scan and then outside the scanner at a separate testing session during which corrugator data were collected. Different picture sets, matched for valence and arousal, were used between the two sessions. Data from the corrugator session are presented here. As outlined in Figure 1, the task utilized a mixed block-event-related design to simultaneously measure states of acute threat and prolonged threat anticipation during a 2-min block period (Somerville et al., 2013). Before each task block, participants viewed a 10-s baseline fixation cross followed by a text screen indicating which experimental condition would be presented. Each 2-min task block included 15 images from the International Affective Picture System (Lang et al., 1998) that were either negative or neutral in valence. Each image was presented for 3 s, and images were separated by an anticipation clock period which lasted 2–7 s. The order of the clock images differed between blocks to make the timing of image presentation predictable (certain) or uncertain. During certain anticipation blocks, clock images were presented in a “countdown” (sequential) order so that participants knew when each picture would appear. During uncertain anticipation blocks, clock images were presented in a random order so that the onset of each picture could not be predicted (Figure 1). Picture valence (negative, neutral) and clock condition (certain, uncertain) were held constant within block, resulting in 4 different conditions (Uncertain-Negative, Certain-Negative, Uncertain-Neutral, Certain-Neutral). Each condition was presented twice (8 blocks total), with condition order counterbalanced across participants. To ensure task attention, participants indicated if the picture portrayed an “indoor” or “outdoor” scene with a keypress.

Experimental paradigm. A series of negative or neutral pictures were presented in a mixed-event block-related design where each 3 s picture presentation is preceded by a series of clocks images (2–7 1-s clock hand images) that either “countdown” to picture presentation (certain timing) or are presented in a random order (uncertain timing). A 2 (negative, neutral) × 2 (certain timing, uncertain timing) task design yields 4 distinct block types (Uncertain-Negative, Certain-Negative, Uncertain-Neutral, Certain-Neutral).

Participant ratings on picture likeability and nervousness during each block type were collected at the end of the session to measure response to images and examine task-evoked anxiety across conditions. Participants rated how much they “liked” a randomized set of 10 neutral and 10 negative images presenting during the task using a 1–5 Likert scale. Participants rated how nervous they felt during each of the 4 block conditions on a 1–9 Likert scale.

2.3 EMG data collection, processing, and analysis

Corrugator EMG was recorded using two 4 mm electrodes placed over the left or right brow region, counterbalanced across participants, in accordance with guidelines provided by Fridlund and colleagues (Fridlund & Cacioppo, 1986). Data were collected using Acqknowledge software, an MP160 high resolution (16 bit) data acquisition system, and an EMG100 C amplifier (BIOPAC Systems Inc., Goleta, CA). Amplifier gain was set at 2000 with 500 Hz low-pass and 1 Hz high-pass filtering at a sampling rate of 2000 Hz. EMG data were processed via a fast Fourier transform on all artifact-free 1-s chunks of data (extracted through Hanning windows with 500 msec overlap) to derive estimates of spectral power density (μV2/Hz) in the 45–200 Hz frequency band every 500 msec. A 58–62 Hz band-reject filter was also applied to account for the 60 Hz alternating current noise. Values were log-transformed to normalize the distribution of activity between participants. Data were baseline-corrected by subtracting the average activity during the 10-s baseline period prior to each block period. Baseline corrugator values did not differ between groups (AD vs. control: Est. = −0.17, p = 0.08; subthreshold-AD vs. control: Est. = −0.16, p = 0.08; subthreshold-AD vs. AD: Est. = 0.01, p = 0.83). Values from each picture exposure and anticipation clock periods were separated and then averaged within each of the 4 conditions to assess task-related changes in corrugator magnitude. Analysis of corrugator activity over time examined averaged time-series of activity across each task condition. See Supporting Information S1 for more details.

2.4 Statistical analyses

Separate linear mixed effects models were used to test effects of certainty, valence, group, and their interactions for self-report and corrugator activity measures. Models examining task-related nervousness, anticipation clock corrugator activity, and picture corrugator activity included 3 fixed effects: certainty (uncertain vs. certain anticipation clock), valence (neutral vs. negative pictures), and group (AD vs. subthreshold-AD vs. Control).

Timecourse examination of corrugator activity utilized a linear mixed effects model that incorporated a linear spline framework to test the effects of group, certainty, valence, and time. To explore potential habituation of the corrugator response throughout the block period, the time parameter of our linear spline analysis included a single knot point placed at the midway point (60-s) of the 2-min response window. This approach provides separate but connected linear slope parameters for the first and second minute of corrugator response. The spline model allows for the detection of different patterns between the early and late portions of the block, as well as linear trends across the full 2-min block period. All models included a by-subject random intercept and random slopes for the certainty and valence parameters to account for repeated measurements across the four conditions.

Analyses were run in R (Team, 2020) using the lme4 (Bates et al., 2015), lmSupport (Curtin, 2018), lspline (Bojanowski, 2017), and HLMdiag (Loy & Hofmann, 2014) packages to run the mixed models, and apply the linear spline transformations. Differences in task-evoked anxiety, picture likeability, corrugator magnitude, and corrugator response trajectories were estimated as a function of fixed effects with t-tests used to measure significance. p-values less than 0.05 were considered significant. Task parameters were numerically coded, scaled from 0 to 1, and were centered to interpret the main effects across the sample. Between group effects were calculated through dummy coding and reference group (AD vs. Control, AD vs. subthreshold-AD, subthreshold-AD vs. Control) model interpretations to provide contrast estimates for each group effect and their interactions. Models examining the relationship between corrugator activity and dimensional measures of anxiety (CGI-A, SCARED-Total) were also examined.

3 RESULTS

3.1 Demographic and clinical characteristics

Participants self-reported their race and ethnicity; we note that participants are predominately white (83%), which may limit generalization of the findings. Age and COI scores did not significantly differ between groups (Table 1). As expected, SCARED (Parent and Child report) and CGI-A scores were significantly different between groups (AD > subthreshold-AD > Control; Table 1). SCARED scores reported in Table 1 were collected ∼3 months (average 93 days) after the initial screening SCARED. At this final SCARED assessment all but one participant in the subthreshold-AD group reported persistent anxiety at the same threshold set during screening (parent or child SCARED >12). As the SCARED reflects anxiety levels over the preceding 3 months, repeated SCARED assessments during screening and during the study capture persistent anxiety over approximately a 6–7 month period.

3.2 Self-report ratings of nervousness and likeability of task stimuli

Post-task nervousness ratings for each condition type (Table 2, Figure S1A) demonstrated a significant main effect of valence (Est. = 1.51, p < 0.001), such that participants reported feeling more nervous during blocks with negative versus neutral pictures. There also was a significant main effect of certainty (Est. = 0.70, p < 0.001) such that all participants rated feeling more nervous during uncertain relative to certain blocks. Both AD and subthreshold-AD girls rated themselves as more nervous during the task compared to controls (AD vs. control: Est. = 1.10, p < 0.001; subthreshold-AD vs. control: Est. = 0.61, p < 0.05). In addition, subthreshold-AD girls rated feeling less nervous during the task compared to AD girls (Est. = −0.49, p < 0.05). Significant anxiety-related interactions with valence were also found between both AD and subthreshold-AD compared to control girls (valence × AD vs. control: Est. = 1.06, p < 0.001; valence × subthreshold-AD vs. control: Est. = 0.78, p < 0.05). These results show that the difference in nervousness ratings during the negative versus neutral conditions were greater in girls with pathological anxiety compared to control girls. For ratings of picture likability (Table 3, Figure S1B), there was a significant main effect of valence (Est. = −1.3, p < 0.001) which demonstrated that all participants rated negative pictures as less likeable than neutral pictures. Likeability ratings of pictures did not differ between groups.

| Estimate | SE | t | df | p | 95% CI | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Lower | Upper | ||||||

| Intercept | 2.50 | 0.10 | 26.04 | 151.03 | <0.001 | 2.31 | 2.69 |

| Certainty | 0.70 | 0.08 | 8.59 | 162.76 | <0.001 | 0.54 | 0.86 |

| Valence | 1.51 | 0.12 | 12.72 | 151.31 | <0.001 | 1.28 | 1.75 |

| Certainty:Valence | 0.17 | 0.13 | 1.32 | 301.99 | 0.19 | −0.08 | 0.42 |

| Control as reference | |||||||

| Subthreshold-AD | 0.61 | 0.24 | 2.52 | 103.92 | <0.05 | 0.14 | 1.09 |

| AD | 1.10 | 0.27 | 4.13 | 292.61 | <0.001 | 0.58 | 1.62 |

| Certainty:Subthreshold-AD | 0.32 | 0.21 | 1.56 | 1120 | 0.12 | −0.08 | 0.73 |

| Certainty:AD | 0.36 | 0.23 | 1.57 | 315.35 | 0.12 | −0.09 | 0.80 |

| Valence:Subthreshold-AD | 0.78 | 0.30 | 2.61 | 104.12 | <0.05 | 0.19 | 1.37 |

| Valence:AD | 1.06 | 0.33 | 3.20 | 293.17 | <0.001 | 0.41 | 1.70 |

| Certainty:Valence:Subthreshold-AD | 0.30 | 0.32 | 0.93 | 207.8 | 0.35 | −0.33 | 0.94 |

| Certainty:Valence:AD | 0.09 | 0.36 | 0.25 | 585.11 | 0.80 | −0.61 | 0.78 |

| AD as reference | |||||||

| Control | −1.1 | 0.27 | −4.13 | 151.03 | <0.001 | −1.62 | −0.58 |

| Subthreshold-AD | −0.49 | 0.23 | −2.17 | 151.03 | <0.05 | −0.93 | −0.05 |

| Certainty:Control | −0.36 | 0.23 | −1.57 | 162.76 | 0.12 | −0.8 | 0.09 |

| Certainty:Subthreshold-AD | −0.03 | 0.19 | −0.17 | 162.76 | 0.86 | −0.41 | 0.34 |

| Valence:Control | −1.06 | 0.33 | −3.2 | 151.31 | <0.001 | −1.7 | −0.41 |

| Valence:Subthreshold-AD | −0.27 | 0.28 | −0.97 | 151.31 | 0.33 | −0.82 | 0.28 |

| Certainty:Valence:Control | −0.09 | 0.36 | −0.25 | 3020 | 0.80 | −0.78 | 0.61 |

| Certainty:Valence:Subthreshold-AD | 0.21 | 0.30 | 0.71 | 3020 | 0.48 | −0.38 | 0.80 |

- Note: Results from linear mixed effects modeling of ratings of nervousness during task conditions as a function of Certainty (Certain vs. Uncertain), Valence (Neutral vs. Negative), and Group (Control vs. subthreshold-AD vs. AD). Group comparison effects are displayed via reference group model estimates; the first using Control as reference and the second using AD as reference. Bold values highlight the p value <0.05.

- Abbreviation: AD, anxiety disorder.

| Estimate | SE | t | df | p | 95% CI | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Lower | Upper | ||||||

| Intercept | 2.48 | 0.04 | 57.51 | 1510 | <0.001 | 2.39 | 2.56 |

| Valence | −1.3 | 0.07 | −17.65 | 1510 | <0.001 | −1.44 | −1.15 |

| Control as reference | |||||||

| Subthreshold-AD | −0.06 | 0.11 | −0.56 | 103.91 | 0.575 | −0.27 | 0.15 |

| AD | −0.21 | 0.12 | −1.73 | 292.57 | 0.085 | −0.44 | 0.03 |

| Valence:Subthreshold-AD | −0.11 | 0.19 | −0.6 | 103.91 | 0.547 | −0.48 | 0.25 |

| Valence:AD | −0.15 | 0.20 | −0.74 | 292.57 | 0.459 | −0.55 | 0.25 |

| AD as reference | |||||||

| Control | 0.21 | 0.12 | 1.73 | 1510 | 0.086 | −0.03 | 0.44 |

| Subthreshold-AD | 0.15 | 0.10 | 1.44 | 1510 | 0.153 | −0.05 | 0.34 |

| Valence:Control | 0.15 | 0.20 | 0.74 | 1510 | 0.460 | −0.25 | 0.55 |

| Valence:Subthreshold-AD | 0.04 | 0.17 | 0.22 | 1510 | 0.823 | −0.3 | 0.38 |

- Note: Results from linear mixed effects modeling of ratings of likeability of picture from the task as a function of Valence (Neutral vs. Negative) and Group (Control vs. subthreshold-AD vs. AD). Group comparison effects are displayed via reference group model estimates; the first using Control as reference and the second using AD as reference. Bold values highlight the p value <0.05.

- Abbreviation: AD, anxiety disorder.

3.3 Average corrugator magnitude during anticipation clock periods

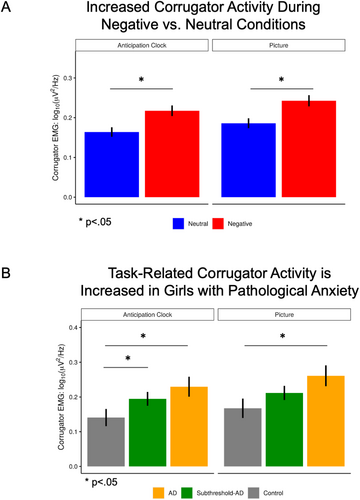

During the anticipation clock periods, we found a main effect of valence where corrugator activity was greater during the anticipation of negative versus neutral pictures (Est. = 0.06, p < 0.001) (Figure 2a, Table 4). Across all conditions, girls with pathological anxiety exhibited significantly higher magnitude relative to controls (AD vs. control: Est. = 0.10, p < 0.05; subthreshold-AD vs. control: Est = 0.07, p < 0.05) while overall magnitude between AD and subthreshold-AD girls did not significantly differ (Est. = −0.03, p = 0.36) (Figure 2b). There was also a significant certainty × valence × subthreshold-AD versus control interaction (Est. = 0.12, p < 0.05), such that while both subthreshold-AD and control girls showed greater activity during negative versus neutral conditions, increased activity during uncertain relative to certain conditions was only observed during the negative blocks of the subthreshold-AD girls, and during the neutral blocks of the control girls. Dimensional analyses of anxiety demonstrate a similar relation between anxiety and corrugator magnitude during anticipation clock periods. For the CGI-A, there was a significant main effect of CGI-A (Est. = 0.02, p < 0.05) such that higher CGI-A scores were associated with increased corrugator activity (Table 5). For SCARED scores there was a positive slope between corrugator magnitude and SCARED scores, but these relations did not reach statistical significance (all Est. < 0.01, all p > 0.15; Tables 6 and 7).

Corrugator magnitude results. (a) Mean corrugator response magnitude during anticipation clock (left) and picture (right) periods across all subjects by valence averaged by negative (red) and neutral (blue) conditions. A significant main effect of valence (negative > neutral) was observed for both the anticipation clock and picture periods (p < 0.05). (b) Mean corrugator response magnitude during anticipation clock (left) and picture (right) periods across all subjects by group: anxiety disorder (AD) (orange), subthreshold-AD (green), control (grey). During the anticipation clock periods, pathological anxiety (AD & subthreshold-AD) was associated with higher corrugator magnitude across all task conditions relative to controls (p < 0.05). During picture viewing corrugator magnitude was increased in AD girls relative to controls (p < 0.05). Asterisks denote significant main effect, p < 0.05. Bars represent mean +/− standard error.

| Estimate | SE | t | df | p | 95% CI | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Lower | Upper | ||||||

| (Intercept) | 0.2 | 0.01 | 14.3 | 156 | <0.001 | 0.17 | 0.22 |

| Certainty | 0.02 | 0.01 | 1.7 | 295 | 0.09 | 0.00 | 0.04 |

| Valence | 0.06 | 0.01 | 4.5 | 157 | <0.001 | 0.03 | 0.08 |

| Certainty:Valence | 3.2E-03 | 0.02 | 0.1 | 312 | 0.89 | −0.04 | 0.05 |

| Control as reference | |||||||

| AD | 0.10 | 0.04 | 2.6 | 156 | <0.05 | 0.02 | 0.17 |

| Subthreshold-AD | 0.07 | 0.03 | 2.0 | 156 | <0.05 | 0.00 | 0.13 |

| Certainty:AD | 0.03 | 0.03 | 1.0 | 295 | 0.30 | −0.03 | 0.10 |

| Valence:AD | 0.06 | 0.04 | 1.7 | 157 | 0.10 | −0.01 | 0.13 |

| Certainty:Subthreshold-AD | −0.01 | 0.03 | −0.3 | 295 | 0.76 | −0.07 | 0.05 |

| Valence:Subthreshold-AD | 0.01 | 0.03 | 0.2 | 157 | 0.86 | −0.06 | 0.07 |

| Certainty:Valence:AD | 0.06 | 0.06 | 0.9 | 312 | 0.37 | −0.07 | 0.19 |

| Certainty:Valence:Subthreshold-AD | 0.12 | 0.06 | 2.0 | 312 | <0.05 | 0.00 | 0.23 |

| AD as reference | |||||||

| Subthreshold-AD | −0.03 | 0.03 | −0.9 | 156 | 0.36 | −0.09 | 0.03 |

| Control | −0.1 | 0.04 | −2.6 | 156 | <0.05 | −0.17 | −0.02 |

| Certainty:Subthreshold-AD | −0.04 | 0.03 | −1.5 | 295 | 0.14 | −0.10 | 0.01 |

| Valence:Subthreshold-AD | −0.05 | 0.03 | −1.7 | 157 | 0.09 | −0.11 | 0.01 |

| Certainty:Control | −0.03 | 0.03 | −1.0 | 295 | 0.30 | −0.10 | 0.03 |

| Valence:Control | −0.06 | 0.04 | −1.7 | 157 | 0.10 | −0.13 | 0.01 |

| Certainty:Valence:Subthreshold-AD | 0.06 | 0.06 | 1.1 | 312 | 0.29 | −0.05 | 0.17 |

| Certainty:Valence:Control | −0.06 | 0.06 | −0.9 | 312 | 0.37 | −0.19 | 0.07 |

- Notes: Results from linear mixed effects modeling of average task-related corrugator reactivity as a function of Certainty (Certain vs. Uncertain), Valence (Neutral vs. Negative) and Group (control vs. subthreshold-AD vs. AD). Group comparison effects are displayed via reference group model estimates; the first using Control as reference and the second using AD as reference. Bold values highlight the p value <0.05.

- Abbreviation: AD, anxiety disorder.

| Estimate | SE | t | df | p | 95% CI | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Lower | Upper | ||||||

| Intercept | 0.13 | 0.03 | 4.28 | 6260 | <0.001 | 0.07 | 0.20 |

| Certainty | 0.03 | 0.03 | 1.12 | 6260 | 0.263 | −0.02 | 0.09 |

| Valence | 2.0e-03 | 0.03 | 0.05 | 6260 | 0.958 | −0.06 | 0.06 |

| CGI-A | 0.02 | 0.01 | 2.04 | 6260 | <0.05 | 1.0e-03 | 0.04 |

| Certainty:Valence | −0.06 | 0.06 | −1.04 | 6260 | 0.298 | −0.18 | 0.05 |

| Certainty:CGI-A | −4.0e-03 | 0.01 | −0.37 | 6260 | 0.714 | −0.02 | 0.02 |

| Valence:CGI-A | 0.02 | 0.01 | 1.97 | 6260 | <0.05 | 0.0e+00 | 0.04 |

| Certainty:Valence:CGI-A | 0.03 | 0.02 | 1.39 | 6260 | 0.164 | −0.01 | 0.07 |

- Notes: Results from linear mixed effects modeling of average task-related corrugator reactivity as a function of certainty (certain vs. uncertain), valence (neutral vs. negative), and Clinical Global Impression Scale (CGI-A). Bold values highlight the p value <0.05.

- Abbreviation: CGI-A, Clinical Global Impression Scale.

| Estimate | SE | t | df | p | 95% CI | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Lower | Upper | ||||||

| Intercept | 0.16 | 0.03 | 6.16 | 6100 | <0.001 | 0.11 | 0.22 |

| Certainty | 0.02 | 0.02 | 10 | 6100 | 0.317 | −0.02 | 0.07 |

| Valence | 0.03 | 0.02 | 1.34 | 6100 | 0.181 | −0.02 | 0.08 |

| SCARED (child) | 1.0e-03 | 1.0e-03 | 1.25 | 6100 | 0.212 | −1.0e-03 | 3.0e-03 |

| Certainty:Valence | −0.05 | 0.05 | −0.93 | 6100 | 0.354 | −0.14 | 0.05 |

| Certainty:SCARED (child) | 0.0e+00 | 1.0e-03 | −0.02 | 6100 | 0.980 | −2.0e-03 | 2.0e-03 |

| Valence:SCARED (child) | 1.0e-03 | 1.0e-03 | 0.99 | 6100 | 0.323 | −1.0e-03 | 3.0e-03 |

| Certainty:Valence:SCARED (child) | 3.0e-03 | 2.0e-03 | 1.43 | 6100 | 0.154 | −1.0e-03 | 0.01 |

- Notes: Results from linear mixed effects modeling of average task-related corrugator activity during the anticipation clock period as a function of certainty (certain vs. uncertain), valence (negative vs. neutral), time (first half, second half), and SCARED (Child). Bold values highlight the p value <0.05.

- Abbreviation: SCARED (Child), Screen for Child Anxiety Related Disorders (Child Report).

| Estimate | SE | t | df | p | 95% CI | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Lower | Upper | ||||||

| Intercept | 0.16 | 0.02 | 6.85 | 6220 | <0.001 | 0.12 | 0.21 |

| Certainty | 0.03 | 0.02 | 1.22 | 6220 | 0.221 | −0.02 | 0.07 |

| Valence | 0.03 | 0.02 | 1.40 | 6220 | 0.161 | −0.01 | 0.08 |

| SCARED (parent) | 2.0e-03 | 1.0e-03 | 1.46 | 6220 | 0.145 | −1.0e-03 | 4.0e-03 |

| Certainty:Valence | −0.04 | 0.04 | −0.99 | 6220 | 0.322 | −0.13 | 0.04 |

| Certainty:SCARED (parent) | 0.0e+00 | 1.0e-03 | −0.27 | 6220 | 0.787 | −2.0e-03 | 2.0e-03 |

| Valence:SCARED (parent) | 1.0e-03 | 1.0e-03 | 1.20 | 6220 | 0.231 | −1.0e-03 | 3.0e-03 |

| Certainty:Valence:SCARED (parent) | 3.0e-03 | 2.0e-03 | 1.53 | 6220 | 0.126 | −1.0e-03 | 0.01 |

- Notes: Results from linear mixed effects modeling of average task-related corrugator activity during the anticipation clock period as a function of certainty (certain vs. uncertain), valence (negative vs. neutral), time (first half, second half), and SCARED (Parent). Bold values highlight the p value <0.05.

- Abbreviation: SCARED (Parent), Screen for Child Anxiety Related Disorders (Parent Report).

3.4 Average corrugator magnitude during picture exposure periods

During picture viewing there was a main effect of valence, such that corrugator magnitude increased more during negative versus neutral pictures (Est. = 0.06, p < 0.001) (Figure 2a, Table 8). Across all pictures, activity in AD girls was significantly greater than control girls (Est. = 0.10, p < 0.05) but did not differ from subthreshold-AD girls (Est. = −0.04, p = 0.20) (Figure 2b). Additionally, activity in subthreshold-AD girls did not significantly differ from control girls (Est. = 0.06, p = 0.11). Similar to the anticipation clock period, there was a significant certainty × valence × subthreshold-AD versus control interaction (Est. = 0.14, p < 0.05). While subthreshold-AD and control girls demonstrate an overall increase in activity across negative versus neutral conditions, activity was not modulated by certainty for subthreshold-AD girls. Within control girls, effects of certainty (uncertain vs. certain) resulted in greater activity in uncertain-neutral versus certain-neutral blocks but in the negative conditions, activity was greater in certain-negative blocks versus uncertain-negative blocks. Dimensional analyses of anxiety demonstrate a similar relation between anxiety and corrugator magnitude during picture exposure periods. For the CGI-A there was a significant main effect of CGI-A (Est. = 0.02, p < 0.05) such that higher CGI-A scores were associated with increased corrugator activity (Table 9). The interaction between CGI-A and valence approached significance (Est.0.02, p = 0.051), such that higher CGI-A scores was associated with a greater difference between corrugator activity during negative versus neutral (negative > neutral) conditions. For SCARED scores, there was a positive slope between average corrugator magnitude and SCARED scores, but these relations did not reach statistical significance (all Est. < 0.01, all p > 0.09: Tables 10 and 11).

| Estimate | SE | t | df | p | 95% CI | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Lower | Upper | ||||||

| (Intercept) | 0.22 | 0.01 | 15.2 | 156 | <0.001 | 0.19 | 0.25 |

| Certainty | 0.01 | 0.01 | 0.6 | 243 | 0.53 | −0.02 | 0.03 |

| Valence | 0.06 | 0.01 | 4.5 | 172 | <0.001 | 0.03 | 0.09 |

| Certainty:Valence | −3.0E-03 | 0.02 | −0.1 | 312 | 0.90 | −0.05 | 0.04 |

| Control as reference | |||||||

| AD versus Control | 0.10 | 0.04 | 2.6 | 156 | <0.05 | 0.03 | 0.18 |

| Subthreshold-AD | 0.06 | 0.04 | 1.6 | 156 | 0.11 | −0.01 | 0.13 |

| Certainty:AD | 0.06 | 0.03 | 1.7 | 243 | 0.10 | −0.01 | 0.12 |

| Valence:AD | 0.06 | 0.04 | 1.5 | 172 | 0.13 | −0.02 | 0.13 |

| Certainty:Subthreshold-AD | 0.01 | 0.03 | 0.2 | 243 | 0.85 | −0.05 | 0.07 |

| Valence:Subthreshold-AD | −3.2E-03 | 0.03 | −0.1 | 172 | 0.92 | −0.07 | 0.06 |

| Certainty:Valence:AD | 0.09 | 0.07 | 1.4 | 312 | 0.17 | −0.04 | 0.22 |

| Certainty:Valence:Subthreshold-AD | 0.14 | 0.06 | 2.3 | 312 | <0.05 | 0.02 | 0.25 |

| AD as reference | |||||||

| Subthreshold-AD | −0.04 | 0.03 | −1.3 | 156 | 0.20 | −0.11 | 0.02 |

| Control | −0.10 | 0.04 | −2.6 | 156 | <0.05 | −0.18 | −0.03 |

| Certainty:Subthreshold-AD | −0.05 | 0.03 | −1.7 | 243 | 0.09 | −0.11 | 0.01 |

| Valence:Subthreshold-AD | −0.06 | 0.03 | −1.8 | 172 | 0.07 | −0.12 | 0.00 |

| Certainty:Control | −0.06 | 0.03 | −1.7 | 243 | 0.10 | −0.12 | 0.01 |

| Valence:Control | −0.06 | 0.04 | −1.5 | 172 | 0.13 | −0.13 | 0.02 |

| Certainty:Valence:Subthreshold-AD | 0.05 | 0.06 | 0.8 | 312 | 0.43 | −0.07 | 0.16 |

| Certainty:Valence:Control | −0.09 | 0.07 | −1.4 | 312 | 0.17 | −0.22 | 0.04 |

- Notes: Results from linear mixed effects modeling of average task-related corrugator reactivity as a function of Certainty (Certain vs. Uncertain), Valence (Neutral vs. Negative) and Group (control vs. subthreshold-AD vs. AD). Group comparison effects are displayed via reference group model estimates; the first using Control as reference and the second using AD as reference. Bold values highlight the p value <0.05.

- Abbreviation: AD, anxiety disorder.

| Picture magnitude | Estimate | SE | t | df | p | 95% CI | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Lower | Upper | ||||||

| Intercept | 0.16 | 0.03 | 4.70 | 6260 | <0.001 | 0.09 | 0.22 |

| Certainty | 0.01 | 0.03 | 0.22 | 6260 | 0.828 | −0.05 | 0.07 |

| Valence | 3.0e-03 | 0.03 | 0.11 | 6260 | 0.910 | −0.06 | 0.06 |

| CGI-A | 0.02 | 0.01 | 2.02 | 6260 | <0.05 | 1.0e-03 | 0.05 |

| Certainty:Valence | −0.08 | 0.06 | −1.37 | 6260 | 0.172 | −0.2 | 0.04 |

| Certainty:CGI-A | 1.0e-03 | 0.01 | 0.12 | 6260 | 0.903 | −0.02 | 0.02 |

| Valence:CGI-A | 0.02 | 0.01 | 1.96 | 6260 | 0.051 | 0.0e+00 | 0.04 |

| Certainty:Valence:CGI-A | 0.04 | 0.02 | 1.64 | 6260 | 0.102 | −0.01 | 0.08 |

- Notes: Results from linear mixed effects modeling of average task-related corrugator reactivity as a function of certainty (certain vs. uncertain), valence (neutral vs. negative), and Clinical Global Impression Scale (CGI-A). Bold values highlight the p value <0.05.

- Abbreviation: CGI-A, Clinical Global Impression Scale.

| Picture magnitude | Estimate | SE | t | df | p | 95% CI | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Lower | Upper | ||||||

| Intercept | 0.19 | 0.03 | 6.75 | 6100 | <0.001 | 0.13 | 0.24 |

| Certainty | 0.01 | 0.03 | 0.37 | 6100 | 0.708 | −0.04 | 0.06 |

| Valence | 0.03 | 0.03 | 10 | 6100 | 0.317 | −0.02 | 0.08 |

| SCARED (child) | 1.0e-03 | 1.0e-03 | 1.12 | 6100 | 0.262 | −1.0e-03 | 3.0e-03 |

| Certainty:Valence | −0.06 | 0.05 | −1.24 | 6100 | 0.215 | −0.16 | 0.04 |

| Certainty:SCARED (child) | 0.0e+00 | 1.0e-03 | 0.11 | 6100 | 0.915 | −2.0e-03 | 2.0e-03 |

| Valence:SCARED (child) | 1.0e-03 | 1.0e-03 | 1.43 | 6100 | 0.152 | −1.0e-03 | 3.0e-03 |

| Certainty:Valence:SCARED (child) | 3.0e-03 | 2.0e-03 | 1.61 | 6100 | 0.107 | −1.0e-03 | 0.01 |

- Notes: results from linear mixed effects modeling of average task-related corrugator activity during the picture period as a function of certainty (certain vs. uncertain), valence (negative vs. neutral), time (first half, second half), and SCARED (Child). Bold values highlight the p value <0.05.

- Abbreviation: SCARED (Child), Screen for Child Anxiety Related Disorders (Child Report).

| Picture magnitude | Estimate | SE | t | df | p | 95% CI | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Lower | Upper | ||||||

| Intercept | 0.18 | 0.02 | 7.24 | 6220 | <0.001 | 0.13 | 0.23 |

| Certainty | −1.0e-03 | 0.02 | −0.04 | 6220 | 0.967 | −0.05 | 0.04 |

| Valence | 0.03 | 0.02 | 1.38 | 6220 | 0.167 | −0.01 | 0.08 |

| SCARED (parent) | 2.0e-03 | 1.0e-03 | 1.68 | 6220 | 0.093 | 0.0e+00 | 4.0e-03 |

| Certainty:Valence | −0.06 | 0.05 | −1.36 | 6220 | 0.176 | −0.15 | 0.03 |

| Certainty:SCARED (parent) | 1.0e-03 | 1.0e-03 | 0.55 | 6220 | 0.582 | −1.0e-03 | 3.0e-03 |

| Valence:SCARED (parent) | 1.0e-03 | 1.0e-03 | 1.29 | 6220 | 0.199 | −1.0e-03 | 3.0e-03 |

| Certainty:Valence:SCARED (parent) | 4.0e-03 | 2.0e-03 | 1.82 | 6220 | 0.068 | 0.0e+00 | 0.01 |

- Notes: Results from linear mixed effects modeling of average task-related corrugator activity during the anticipation clock period as a function of certainty (certain vs. uncertain), valence (negative vs. neutral), time (first half, second half), and SCARED (Parent). Bold values highlight the p value <0.05.

- Abbreviation: SCARED (Parent), Screen for Child Anxiety Related Disorders (Parent Report).

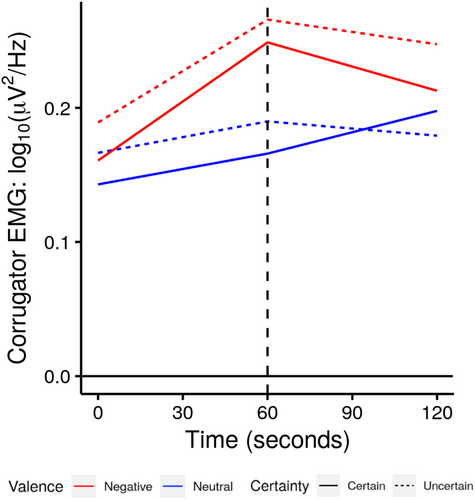

3.5 Task-related effects on corrugator activity over time

When examining task modulation of the corrugator response over time, similar to the averaged corrugator magnitude models, there was a significant main effect of valence (Est. = 0.08, p < 0.001) demonstrating greater activity during negative versus neutral conditions (Table 12). Unlike the averaged magnitude analyses, the trajectory of corrugator response over time demonstrated a significant main effect of certainty (Est. = 0.02, p < 0.001) showing greater responding during the uncertain versus certain conditions. Within this linear spline model, main and interaction effects related to time were simultaneously estimated for the first and second halves of the 2-min task blocks. There was a significant main effect of time in both the first (Est. = 0.11, p < 0.001) and second (Est. = −0.02, p < 0.001) halves of the block, such that, on average, activity increased during the first half, and subsequently decreased during the second half (Figure 3, Table 12).

| Estimate | SE | t | df | p | 95% CI | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Lower | Upper | ||||||

| Intercept | 0.22 | 0.01 | 15.52 | 158.06 | <0.001 | 0.19 | 0.24 |

| Certainty | 0.02 | 3.0e-03 | 7.83 | 153,084 | <0.001 | 0.02 | 0.03 |

| Valence | 0.08 | 3.0e-03 | 30.34 | 153,084 | <0.001 | 0.07 | 0.08 |

| Time (first half) | 0.11 | 5.0e-03 | 20.92 | 153,084 | <0.001 | 0.10 | 0.12 |

| Time (second half) | −0.02 | 5.0e-03 | −3.3 | 153,084 | <0.001 | −0.03 | −0.01 |

| Certainty:Valence | −0.01 | 5.0e-03 | −1.34 | 153,084 | 0.18 | −0.02 | 3.0e-03 |

| Certainty:Time (first half) | −0.01 | 0.01 | −1.08 | 153,084 | 0.28 | −0.03 | 0.01 |

| Certainty:Time (second half) | −0.02 | 0.01 | −2.46 | 153,084 | <0.05 | −0.04 | −5.0e-03 |

| Valence:Time (first half) | 0.12 | 0.01 | 11.72 | 153,084 | <0.001 | 0.10 | 0.14 |

| Valence:Time (second half) | −0.08 | 0.01 | −7.49 | 153,084 | <0.001 | −0.1 | −0.06 |

| Certainty:Valence:Time (first half) | −0.02 | 0.02 | −1.18 | 153,084 | 0.24 | −0.06 | 0.02 |

| Certainty:Valence:Time (second half) | 0.12 | 0.02 | 5.96 | 153,084 | <0.001 | 0.08 | 0.16 |

| Control as reference | |||||||

| AD | 0.10 | 0.04 | 2.54 | 266.15 | <0.05 | 0.02 | 0.17 |

| Subthreshold-AD | 0.05 | 0.04 | 1.36 | 105.54 | 0.18 | −0.02 | 0.11 |

| Certainty:AD | 0.01 | 0.01 | 1.42 | 257,774.94 | 0.16 | −4.0e-03 | 0.02 |

| Valence:AD | 0.09 | 0.01 | 12.38 | 257,774.94 | <0.001 | 0.07 | 0.10 |

| Time (first half):AD | 0.03 | 0.01 | 2.47 | 257,774.94 | <0.05 | 0.01 | 0.06 |

| Time (second half):AD | 1.0e-03 | 0.01 | 0.09 | 257,774.94 | 0.93 | −0.03 | 0.03 |

| Certainty:Subthreshold-AD | −0.01 | 0.01 | −0.88 | 102,216.71 | 0.38 | −0.02 | 0.01 |

| Valence:Subthreshold-AD | −0.02 | 0.01 | −3.02 | 102,216.71 | <0.001 | −0.03 | −0.01 |

| Time (first half):Subthreshold-AD | −0.01 | 0.01 | −0.98 | 102,216.71 | 0.33 | −0.04 | 0.01 |

| Time (second half):Subthreshold-AD | 0.02 | 0.01 | 1.82 | 102,216.71 | 0.07 | −2.0e-03 | 0.05 |

| Certainty:Valence:AD | 0.05 | 0.01 | 3.55 | 257,774.94 | <0.001 | 0.02 | 0.08 |

| Certainty:Time (first half):AD | −0.02 | 0.03 | −0.7 | 257,774.94 | 0.48 | −0.07 | 0.04 |

| Certainty:Time (second half):AD | 0.04 | 0.03 | 1.29 | 257,774.94 | 0.20 | −0.02 | 0.09 |

| Valence:Time (first half):AD | 0.19 | 0.03 | 6.78 | 257,774.94 | <0.001 | 0.13 | 0.24 |

| Valence:Time (second half):AD | −0.14 | 0.03 | −4.93 | 257,774.94 | <0.001 | −0.19 | −0.08 |

| Certainty:Valence:Subthreshold-AD | 0.04 | 0.01 | 3.14 | 102,216.71 | <0.001 | 0.02 | 0.07 |

| Certainty:Time (first half):Subthreshold-AD | −0.06 | 0.02 | −2.42 | 102,216.71 | <0.05 | −0.11 | −0.01 |

| Certainty:Time (second half):Subthreshold-AD | −0.06 | 0.02 | −2.42 | 102,216.71 | <0.05 | −0.11 | −0.01 |

| Valence:Time (first half):Subthreshold-AD | −0.11 | 0.02 | −4.46 | 102,216.71 | <0.001 | −0.16 | −0.06 |

| Valence:Time (second half):Subthreshold-AD | 0.02 | 0.02 | 0.64 | 102,216.71 | 0.52 | −0.03 | 0.06 |

| Certainty:Valence:Time (first half):AD | 0.03 | 0.06 | 0.53 | 257,774.94 | 0.59 | −0.08 | 0.14 |

| Certainty:Valence:Time (second half):AD | 0.27 | 0.06 | 4.96 | 257,774.94 | <0.001 | 0.16 | 0.38 |

| Certainty:Valence:Time (first half):Subthreshold-AD | −0.08 | 0.05 | −1.58 | 102,216.71 | 0.11 | −0.18 | 0.02 |

| Certainty:Valence:Time (second half):Subthreshold-AD | 0.29 | 0.05 | 5.79 | 102,216.71 | <0.001 | 0.19 | 0.38 |

| AD as reference | |||||||

| Subthreshold-AD | −0.05 | 0.03 | −1.49 | 158.06 | 0.14 | −0.12 | 0.02 |

| Control | −0.1 | 0.04 | −2.54 | 158.06 | <0.05 | −0.17 | −0.02 |

| Certainty:Subthreshold-AD | −0.02 | 0.01 | −2.53 | 153,084 | <0.05 | −0.03 | −4.0e-03 |

| Valence:Subthreshold-AD | −0.11 | 0.01 | −17.21 | 153,084 | <0.001 | −0.12 | −0.1 |

| Time (first half):Subthreshold-AD | −0.05 | 0.01 | −3.83 | 153,084 | <0.001 | −0.07 | −0.02 |

| Time (second half):Subthreshold-AD | 0.02 | 0.01 | 1.78 | 153,084 | 0.08 | −2.0e-03 | 0.04 |

| Certainty:Control | −0.01 | 0.01 | −1.42 | 153,084 | 0.16 | −0.02 | 4.0e-03 |

| Valence:Control | −0.09 | 0.01 | −12.38 | 153,084 | <0.001 | −0.1 | −0.07 |

| Time (first half):Control | −0.03 | 0.01 | −2.47 | 153,084 | <0.05 | −0.06 | −0.01 |

| Time (second half):Control | −1.0e-03 | 0.01 | −0.09 | 153,084 | 0.93 | −0.03 | 0.03 |

| Certainty:Valence:Subthreshold-AD | −0.01 | 0.01 | −0.81 | 153,084 | 0.42 | −0.04 | 0.01 |

| Certainty:Time (first half):Subthreshold-AD | −0.04 | 0.02 | −1.69 | 153,084 | 0.09 | −0.09 | 0.01 |

| Certainty:Time (second half):Subthreshold-AD | −0.1 | 0.02 | −3.96 | 153,084 | <0.001 | −0.14 | −0.05 |

| Valence:Time (first half):Subthreshold-AD | −0.3 | 0.02 | −12.32 | 153,084 | <0.001 | −0.34 | −0.25 |

| Valence:Time (second half):Subthreshold-AD | 0.15 | 0.02 | 6.28 | 153,084 | <0.001 | 0.10 | 0.20 |

| Certainty:Valence:Control | −0.05 | 0.01 | −3.55 | 153,084 | <0.001 | −0.08 | −0.02 |

| Certainty:Time (first half):Control | 0.02 | 0.03 | 0.70 | 153,084 | 0.48 | −0.04 | 0.07 |

| Certainty:Time (second half):Control | −0.04 | 0.03 | −1.29 | 153,084 | 0.20 | −0.09 | 0.02 |

| Valence:Time (first half):Control | −0.19 | 0.03 | −6.78 | 153,084 | <0.001 | −0.24 | −0.13 |

| Valence:Time (second half):Control | 0.14 | 0.03 | 4.93 | 153,084 | <0.001 | 0.08 | 0.19 |

| Certainty:Valence:Time (first half):Subthreshold-AD | −0.11 | 0.05 | −2.24 | 153,084 | <0.05 | −0.2 | −0.01 |

| Certainty:Valence:Time (second half):Subthreshold-AD | 0.02 | 0.05 | 0.31 | 153,084 | 0.75 | −0.08 | 0.11 |

| Certainty:Valence:Time (first half):Control | −0.03 | 0.06 | −0.53 | 153,084 | 0.59 | −0.14 | 0.08 |

| Certainty:Valence:Time (second half):Control | −0.27 | 0.06 | −4.96 | 153,084 | <0.001 | −0.38 | −0.16 |

- Notes: Results from linear mixed effects modeling of average task-related corrugator activity as a function of Certainty (Certain vs. Uncertain), Valence (Neutral vs. Negative), time (first half, second half and Group (control vs. subthreshold-AD vs. AD). Group comparison effects are displayed via reference group model estimates; the first using Control as reference and the second using AD as reference. Bold values highlight the p value <0.05.

- Abbreviation: AD, anxiety disorder.

Average corrugator activity over time as predicted by the linear mixed effects model. Vertical black dashed line represents the knot point at 60 s that splits the response into splines that encompass the first and second half of the corrugator response during the task block. Line color represents condition valence: negative (red) & neutral (blue). Line type represents condition certainty: uncertain (dashed) & certain (solid).

During the first half block, there was a significant valence × time interaction (Est. = 0.12, p < 0.001) demonstrating that corrugator activity increased more rapidly during the negative versus neutral conditions. During the second half of the block, there was a significant certainty × valence × time interaction (Est. = 0.12, p < 0.001). Deconstructing this interaction revealed that activity was relatively sustained during uncertain-negative conditions compared to decreasing activity in the certain-negative conditions. Unexpectedly, for the uncertain-neutral condition, activity decreased over time, whereas activity increased over time during the certain-neutral condition (Figure 3, Table 12).

3.6 Anxiety-related effects on corrugator activity over time

3.6.1 AD versus control

Consistent with the magnitude analyses, average corrugator activity was significantly greater in AD versus control girls (Est. = 0.10, p < 0.05) (Figure 4a, Table 12). Additionally, there was a significant valence × AD versus Control interaction (Est. = 0.09, p < 0.001) where the difference in average corrugator activity between negative and neutral conditions (negative > neutral) was greater in AD girls compared to control girls (Figure 4b, Table 12). There was also a significant certainty × valence × AD versus Control interaction (Est. = 0.05, p < 0.001) (Figure 4a, Table 12). Similar to the magnitude results, this interaction captures greater uncertainty-related differences in the negative conditions in AD girls (uncertain > certain) versus control girls, and greater uncertainty-related differences in the neutral conditions in control girls (uncertain > certain).

Average corrugator activity over time separated by group as predicted by linear mixed effects model. Vertical black dashed line represents the knot point at 60 s that splits the response into splines that encompass the first and second half of the corrugator response during the task block. (a) Corrugator activity over time by anxiety group and condition. (b) Corrugator activity over time by anxiety group and valence averaged by negative (red) and neutral (blue) conditions. (c) Corrugator activity over time by anxiety group and certainty averaged by uncertain (dashed) and certain (solid) conditions.

In the first half of the block, there was a significant valence × time × AD versus Control interaction (Est. = 0.19, p < 0.001), indicating a difference in the slope of corrugator activity during the first half of the block for negative conditions versus neutral conditions between AD and controls girls. Specifically, for AD girls corrugator activity increased more rapidly during negative blocks, compared to neutral blocks, whereas the difference in corrugator change over time between negative and neutral blocks was more modest for control girls (Figure 4b, Table 8). In the second half of the block there was a significant Certainty × Valence × Time × AD versus Control interaction (Est. = 0.27, p < 0.001). To visualize this interaction, Figure 5 displays corrugator response over time for the contrast of [Uncertain Negative–Certain Negative]–[Uncertain Neutral–Certain Neutral] conditions, which reflects the difference between the effect on corrugator associated with the uncertain timing, relative to certain timing, of the presentation of negative images, compared to the same contrast for neutral images. The positive slope for the AD group during the second half of the block demonstrates that uncertain timing of the presentation of negative images is associated with increasing corrugator over time for AD girls. In contrast, control girls show the opposite pattern.

Corrugator trajectories over time for contrast [Uncertain Negative–Certain Negative]–[Uncertain Neutral–Certain Neutral]. This contrast reflects the difference between the effect on corrugator associated with the uncertain timing, relative to certain timing, of the presentation of negative images, compared to the same contrast for neutral images. Vertical black dashed line represents the knot point at 60 s that splits the response into splines that encompass the first and second half of the corrugator response during the task block. Colors represent each diagnostic group: AD (Orange), subthreshold-AD (Green), control (gray). The positive slope for the AD and subthreshold-AD group during the second half of the block demonstrates that uncertain timing of the presentation of negative images is associated increasing corrugator over time for girls with pathological anxiety. In contrast, control girls show the opposite pattern.

3.6.2 Subthreshold-AD versus control

There was a significant Valence × Subthreshold-AD versus Control interaction (Est. = −0.02, p < 0.001) indicating that the difference in corrugator activity between negative versus neutral conditions (negative > neutral) was greater in control girls compared to subthreshold-AD girls (Figure 4b, Table 8). There was also a significant Certainty × Valence × Subthreshold-AD versus Control interaction (Est. = 0.04, p < 0.001), such that for subthreshold-AD girls corrugator activity was modulated by uncertainty during negative conditions (uncertain > certain), whereas for Control girls demonstrated uncertainty effects on corrugator in the neutral conditions (uncertain > certain) (Figure 4a, Table 12).

During the first half of the task blocks, there was a significant Valence × Time × Subthreshold-AD versus Control (Est. = −0.11, p < 0.001) interaction, demonstrating that for control girls corrugator activity increased more rapidly in the negative conditions, relative to neutral conditions, whereas for subthreshold-AD girls corrugator change over time was more similar between negative and neutral blocks (Figure 4b, Table 12). There was also a significant Certainty × Time × Subthreshold-AD versus Control interaction in the first half of the block (Est. = −0.06, p < 0.05), such that for control girls corrugator activity increased more rapidly in the uncertain conditions versus certain conditions, whereas for subthreshold-AD girls corrugator activity increased more rapidly in the certain conditions, relative to uncertain conditions (Figure 4c, Table 12). In the second half of the block there was a significant Certainty × Valence × Time × Subthreshold-AD versus Control interaction (Est. = 0.29, p < 0.001). As shown in Figure 5, similar to the AD versus control comparison, subthreshold-AD girls have a positive trajectory in the second half of the block, demonstrating that uncertainty during the negative blocks (as compared to neutral blocks) is associated with increased corrugator over time. Control girls have a negative slope during the second half of the block for this contrast.

3.6.3 Subthreshold-AD versus AD

There was a significant Certainty × Subthreshold-AD versus AD interaction (Est. = −0.02, p < 0.05) which demonstrated that the difference in corrugator activity between uncertain versus certain conditions was greater in AD versus subthreshold-AD girls (Figure 4c, Table 8). Additionally, there was a significant Valence × Subthreshold-AD versus AD interaction (Est. = −0.11, p < 0.001) such that the difference in corrugator activity between negative versus neutral conditions was greater in AD versus subthreshold-AD girls (Figure 4b, Table 8).

For the first half of the task, there as a significant Certainty × Valence × Time × Subthreshold-AD versus AD interaction (Est. = −0.11, p < 0.05), such that during the first half of the task blocks, AD girls demonstrated increasing corrugator activity over time for uncertain negative blocks, whereas subthreshold-AD girls had the opposite pattern (Figure 5). During the second half of the block, there were significant Valence × Time × Subthreshold-AD versus AD interactions (Est. = 0.15, p < 0.001), such that for AD girls corrugator activity decreased more rapidly for negative, relative to neutral, conditions, whereas for subthreshold-AD girls corrugator activity over time was more similar for negative and neutral blocks (Figure 4b, Table 8). During the second half of the task blocks there was also a significant Certainty × Time × Subthreshold-AD versus AD interaction (Est. = −0.1, p < 0.001), such that for AD girls corrugator activity was more sustained for uncertain versus certain conditions, and for subthreshold-AD girls corrugator activity increased over time for certain conditions and decreased over time for uncertain conditions (Figure 4c, Table 12).

3.6.4 Dimensional measures of anxiety–CGI-A, SCARED parent and SCARED child

Dimensional analyses of anxiety demonstrate a similar relationship between anxiety severity and corrugator activity over time. The CGI-A, SCARED Parent and SCARED Child all demonstrated a significant Valence × Time × anxiety scale interaction in the first (all p < 0.001) and second (all p < 0.001) halves of the task blocks (Tables 13–15). Similar to the anxiety group analyses, these interactions demonstrated that higher CGI-A, SCARED Parent and SCARED Child scores were associated with more rapid increases in corrugator activity during the negative versus neutral (negative > neutral) conditions in the first half, and a more rapid decrease in activity during the negative versus neutral (negative < neutral) conditions during the second half of the block. During the second half of the block, the CGI-A, SCARED Parent and SCARED Child all demonstrated a significant Certainty × Valence × Time × anxiety scale interaction (all p < 0.05; Tables 13–15). Consistent with the anxiety group analyses, higher CGI-A, SCARED Parent and SCARED Child scores were associated with increasing corrugator over time for uncertain (vs. certain) negative blocks, relative to the same contrast for neutral blocks.

| Estimate | SE | t | df | p | 95% CI | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Lower | Upper | ||||||

| Intercept | 0.16 | 0.03 | 5.09 | 153,250 | <0.001 | 0.10 | 0.22 |

| Certainty | 0.03 | 0.01 | 5.63 | 153,250 | <0.001 | 0.02 | 0.04 |

| Valence | 0.0e+00 | 0.01 | 0.74 | 153,250 | 0.458 | −0.01 | 0.02 |

| Time (first half) | 0.10 | 0.01 | 8.63 | 153,250 | <0.001 | 0.08 | 0.12 |

| Time (second half) | −0.05 | 0.01 | −4.56 | 153,250 | <0.001 | −0.07 | −0.03 |

| CGI-A | 0.02 | 0.01 | 1.97 | 153,250 | <0.05 | 0.0e+00 | 0.05 |

| Certainty:Valence | −0.07 | 0.01 | −5.89 | 153,250 | <0.001 | −0.09 | −0.05 |

| Certainty:Time (first half) | 0.0e+00 | 0.02 | −0.18 | 153,250 | 0.854 | −0.05 | 0.04 |

| Certainty:Time (second half) | −0.08 | 0.02 | −3.72 | 153,250 | <0.001 | −0.13 | −0.04 |

| Valence:Time (first half) | 0.03 | 0.02 | 1.22 | 153,250 | 0.224 | −0.02 | 0.07 |

| Valence:Time (second half) | 0.02 | 0.02 | 0.97 | 153,250 | 0.332 | −0.02 | 0.07 |

| Certainty:CGI-A | −0.01 | 2.0e-03 | −2.41 | 153,250 | <0.05 | −0.01 | 0.0e+00 |

| Valence:CGI-A | 0.03 | 2.0e-03 | 14.14 | 153,250 | <0.001 | 0.03 | 0.03 |

| Time (first half):CGI-A | 0.0e+00 | 4.0e-03 | 0.70 | 153,250 | 0.485 | −0.01 | 0.01 |

| Time (second half):CGI-A | 0.01 | 4.0e-03 | 3.46 | 153,250 | <0.05 | 0.01 | 0.02 |

| Certainty:Valence:Time (first half) | −0.03 | 0.05 | −0.71 | 153,250 | 0.479 | −0.12 | 0.06 |

| Certainty:Valence:Time (second half) | 0.0e+00 | 0.05 | −0.08 | 153,250 | 0.937 | −0.09 | 0.09 |

| Certainty:Valence:CGI-A | 0.03 | 4.0e-03 | 5.91 | 153,250 | <0.001 | 0.02 | 0.03 |

| Certainty:Time (first half):CGI-A | 0.0e+00 | 0.01 | −0.33 | 153,250 | 0.744 | −0.02 | 0.01 |

| Certainty:Time (second half):CGI-A | 0.02 | 0.01 | 2.93 | 153,250 | <0.05 | 0.01 | 0.04 |

| Valence:Time (first half):CGI-A | 0.04 | 0.01 | 4.43 | 153,250 | <0.001 | 0.02 | 0.05 |

| Valence:Time (second half):CGI-A | −0.04 | 0.01 | −4.78 | 153,250 | <0.001 | −0.06 | −0.02 |

| Certainty:Valence:Time (first half):CGI-A | 0.0e+00 | 0.02 | 0.21 | 153,250 | 0.837 | −0.03 | 0.04 |

| Certainty:Valence:Time (second half):CGI-A | 0.05 | 0.02 | 3.03 | 153,250 | <0.05 | 0.02 | 0.08 |

- Notes: Results from linear mixed effects modeling of average task-related corrugator activity as a function of certainty (certain vs. uncertain), valence (negative vs. neutral), time (first half, second half), and CGI-A. Bold values highlight the p value <0.05.

- Abbreviation: CGI-A, Clinical Global Impression Scale.

| SCARED (child) | Estimate | SE | t | df | p | 95% CI | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Lower | Upper | ||||||

| Intercept | 0.19 | 0.03 | 7.14 | 149,394 | <0.001 | 0.14 | 0.25 |

| Certainty | 0.02 | 5.0e-03 | 3.92 | 149,394 | <0.001 | 0.01 | 0.03 |

| Valence | 0.04 | 5.0e-03 | 7.66 | 149,394 | <0.001 | 0.03 | 0.05 |

| Time (first half) | 0.11 | 0.01 | 11.76 | 149,394 | <0.001 | 0.09 | 0.13 |

| Time (second half) | −0.02 | 0.01 | −2.52 | 149,394 | <0.05 | −0.04 | −0.01 |

| SCARED (child) | 0.0e+00 | 1.0e-03 | 1.15 | 149,394 | 0.251 | 0.0e+00 | 0.0e+00 |

| Certainty:Valence | −0.05 | 0.01 | −5.09 | 149,394 | <0.001 | −0.07 | −0.03 |

| Certainty:Time (first half) | −0.04 | 0.02 | −2.26 | 149,394 | <0.05 | −0.08 | −0.01 |

| Certainty:Time (second half) | −0.04 | 0.02 | −2.1 | 149,394 | <0.05 | −0.08 | 0.0e+00 |

| Valence:Time (first half) | 0.03 | 0.02 | 1.51 | 149,394 | 0.131 | −0.01 | 0.07 |

| Valence:Time (second half) | −0.02 | 0.02 | −0.93 | 149,394 | 0.350 | −0.05 | 0.02 |

| Certainty:SCARED (child) | 0.0e+00 | 0.0e+00 | 1.06 | 149,394 | 0.289 | 0.0e+00 | 0.0e+00 |

| Valence:SCARED (child) | 0.0e+00 | 0.0e+00 | 10.09 | 149,394 | <0.001 | 0.0e+00 | 0.0e+00 |

| Time (first half):SCARED (child) | 0.0e+00 | 0.0e+00 | −0.27 | 149,394 | 0.786 | 0.0e+00 | 0.0e+00 |

| Time (second half):SCARED (child) | 0.0e+00 | 0.0e+00 | 0.94 | 149,394 | 0.348 | 0.0e+00 | 0.0e+00 |

| Certainty:Valence:Time (first half) | −0.02 | 0.04 | −0.48 | 149,394 | 0.630 | −0.09 | 0.06 |

| Certainty:Valence:Time (second half) | −0.01 | 0.04 | −0.14 | 149,394 | 0.885 | −0.08 | 0.07 |

| Certainty:Valence:SCARED (child) | 0.0e+00 | 0.0e+00 | 5.26 | 149,394 | <0.001 | 0.0e+00 | 0.0e+00 |

| Certainty:Time (first half):SCARED (child) | 0.0e+00 | 1.0e-03 | 2.33 | 149,394 | <0.05 | 0.0e+00 | 0.0e+00 |

| Certainty:Time (second half):SCARED (child) | 0.0e+00 | 1.0e-03 | 0.36 | 149,394 | 0.716 | 0.0e+00 | 0.0e+00 |

| Valence:Time (first half):SCARED (child) | 0.0e+00 | 1.0e-03 | 5.51 | 149,394 | <0.001 | 0.0e+00 | 0.01 |

| Valence:Time (second half):SCARED (child) | 0.0e+00 | 1.0e-03 | −3.61 | 149,394 | <0.001 | 0.0e+00 | 0.0e+00 |

| Certainty:Valence:Time (first half):SCARED (child) | 0.0e+00 | 1.0e-03 | −0.24 | 149,394 | 0.814 | 0.0e+00 | 0.0e+00 |

| Certainty:Valence:Time (second half):SCARED (child) | 0.01 | 1.0e-03 | 3.87 | 149,394 | <0.001 | 0.0e+00 | 0.01 |

- Notes: Results from linear mixed effects modeling of average task-related corrugator activity as a function of certainty (certain vs. uncertain), valence (negative vs. neutral), and time (first half, second half), and SCARED (Child). Bold values highlight the p value <0.05.

- Abbreviation: SCARED (Child), Screen for Child Anxiety Related Disorders (Child Report).

| SCARED (parent) | Estimate | SE | t | df | p | 95% CI | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Lower | Upper | ||||||

| Intercept | 0.19 | 0.02 | 7.84 | 152,286 | <0.001 | 0.14 | 0.24 |

| Certainty | 0.02 | 4.0e-03 | 3.94 | 152,286 | <0.001 | 0.01 | 0.03 |

| Valence | 0.04 | 4.0e-03 | 8.17 | 152,286 | <0.001 | 0.03 | 0.05 |

| Time (first half) | 0.12 | 0.01 | 13.54 | 152,286 | <0.001 | 0.10 | 0.13 |

| Time (second half) | −0.03 | 0.01 | −3.22 | 152,286 | <0.05 | −0.04 | −0.01 |

| SCARED (parent) | 0.0e+00 | 1.0e-03 | 1.47 | 152,286 | 0.142 | 0.0e+00 | 0.0e+00 |

| Certainty:Valence | −0.07 | 0.01 | −7.63 | 152,286 | <0.001 | −0.09 | −0.05 |

| Certainty:Time (first half) | −0.02 | 0.02 | −1.45 | 152,286 | 0.147 | −0.06 | 0.01 |

| Certainty:Time (second half) | −0.04 | 0.02 | −2.05 | 152,286 | <0.05 | −0.07 | 0.0e+00 |

| Valence:Time (first half) | 0.04 | 0.02 | 2.60 | 152,286 | <0.05 | 0.01 | 0.08 |

| Valence:Time (second half) | 0.02 | 0.02 | 1.03 | 152,286 | 0.303 | −0.02 | 0.05 |

| Certainty:SCARED (parent) | 0.0e+00 | 0.0e+00 | 0.50 | 152,286 | 0.615 | 0.0e+00 | 0.0e+00 |

| Valence:SCARED (parent) | 0.0e+00 | 0.0e+00 | 11.73 | 152,286 | <0.001 | 0.0e+00 | 0.0e+00 |

| Time (first half):SCARED (parent) | 0.0e+00 | 0.0e+00 | −1.57 | 152,286 | 0.116 | 0.0e+00 | 0.0e+00 |

| Time (second half):SCARED (parent) | 0.0e+00 | 0.0e+00 | 1.46 | 152,286 | 0.144 | 0.0e+00 | 0.0e+00 |

| Certainty:Valence:Time (first half) | −0.12 | 0.03 | −3.43 | 152,286 | <0.05 | −0.19 | −0.05 |

| Certainty:Valence:Time (second half) | 0.04 | 0.03 | 1.14 | 152,286 | 0.256 | −0.03 | 0.11 |

| Certainty:Valence:SCARED (parent) | 0.0e+00 | 0.0e+00 | 8.16 | 152,286 | <0.001 | 0.0e+00 | 0.0e+00 |

| Certainty:Time (first half):SCARED (parent) | 0.0e+00 | 1.0e-03 | 0.89 | 152,286 | 0.371 | 0.0e+00 | 0.0e+00 |

| Certainty:Time (second half):SCARED (parent) | 0.0e+00 | 1.0e-03 | 0.85 | 152,286 | 0.394 | 0.0e+00 | 0.0e+00 |

| Valence:Time (first half):SCARED (parent) | 0.0e+00 | 1.0e-03 | 5.43 | 152,286 | <0.001 | 0.0e+00 | 0.01 |

| Valence:Time (second half):SCARED (parent) | −0.01 | 1.0e-03 | −6.74 | 152,286 | <0.001 | −0.01 | 0.0e+00 |

| Certainty:Valence:Time (first half):SCARED (parent) | 0.0e+00 | 2.0e-03 | 3.28 | 152,286 | <0.05 | 0.0e+00 | 0.01 |

| Certainty:Valence:Time (second half):SCARED (parent) | 0.0e+00 | 2.0e-03 | 3.16 | 152,286 | <0.05 | 0.0e+00 | 0.01 |

- Notes: Results from linear mixed effects modeling of average task-related corrugator activity as a function of certainty (certain vs. uncertain), valence (negative vs. neutral), and time (first half, second half), and SCARED (Parent). Bold values highlight the p value <0.05.

- Abbreviation: SCARED (Parent), Screen for Child Anxiety Related Disorders (Parent Report).

4 DISCUSSION

In this study, we sought to understand potential alterations in corrugator responding in girls across the spectrum of pathological anxiety by characterizing responses to threat and uncertainty. Consistent with previous work with this paradigm (Somerville et al., 2013), results from self-report ratings demonstrated main effects of valence and certainty, such that participants reported feeling more nervous during negative and uncertain conditions. Task-related corrugator activity showed a similar valence effect, with increased activity during negative versus neutral conditions. Certainty was not found to significantly modulate average corrugator response.

Examination of task-related group differences revealed both self-reported and physiological anxiety-related differences. Average self-reported nervousness across all conditions was greater in AD and subthreshold-AD girls versus control girls. Nervousness ratings were also greater in AD versus subthreshold-AD girls. Both AD and subthreshold-AD girls demonstrated a larger valence effect, reporting higher nervousness for negative conditions as compared to controls. Examination of corrugator magnitude demonstrated that girls with ADs, compared to controls, had greater activity across all task conditions during the anticipation clock and picture exposure periods. Similarly, subthreshold-AD girls had greater activity during the anticipation clock period versus control girls. Taken together, these results demonstrate similarities in physiological responding across subthreshold-AD and AD girls that differs from control participants, providing support for anxiety-related pathophysiological alterations that extend beyond the traditional diagnostic categories.

To our knowledge, no studies have reported differences in corrugator magnitude in adults or children with ADs. However, one study in healthy adults has linked higher levels of state anxiety to increased corrugator activity during the viewing of negative images (Smith et al., 2005). Previous studies using other physiological measures (heart rate, skin conductance, eye-blink response), which primarily examined negative valence responses, have demonstrated increased physiological reactivity in individuals with ADs (McTeague et al., 2011; McTeague & Lang, 2012). Our current findings demonstrating anxiety-related increases in corrugator reactivity during the anticipation and presentation of negative and neutral stimuli are consistent with studies that found increased physiological reactivity in individuals with ADs across various conditions and contexts (Abend et al., 2019, 2021; Duits et al., 2015; Dvir et al., 2019).

The design of our threat anticipation task also allowed for characterization of the trajectory of corrugator responding. The most prominent effects relevant to pathological anxiety are evident during the second half of the task block, with AD and subthreshold-AD girls demonstrating a significantly different pattern from control girls. Consistent with our predictions, both AD and subthreshold-AD girls had increasing corrugator responses over time that were associated with the uncertain, relative to certain, timing of negative images, when compared to the same contrast for neutral images (Figure 5). In contrast, control girls show the opposite pattern. Significant differences were not found when comparing responses between AD and subthreshold-AD girls. During the first half of the task block, the same contrast revealed significant differences between the AD and subthreshold-AD groups in the expected direction, however neither pathological anxiety group differed from controls (Figure 5, Table 12). A similar relation was found when anxiety was modeled dimensionally (CGI-A, SCARED Parent, SCARED Child; Tables 13–15).

Some of the corrugator trajectory results for the first half of the task block were consistent with our expectations, but some were not. Specifically, during the first half of the task block differences were observed between the negative and neutral conditions, characterized by the AD group demonstrating a greater difference in the rate of rise in corrugator activity in response to negative versus neutral stimuli, when compared with subthreshold-AD and control girls. When comparing subthreshold-AD and control girls, a greater difference in rate of rise was observed in the control group. There were also effects on the trajectory of corrugator activity over time in first half of the task blocks when comparing across uncertain and certain conditions. Here subthreshold-AD girls demonstrated a different pattern from the other two groups, such that for both control and AD girls the rate of rise during certain blocks was greater relative to uncertain blocks, whereas similar rates of rise for certain and uncertain conditions were seen for subthreshold-AD group.

The relation between pathological anxiety and uncertainty-related effects on corrugator activity during negative task conditions revealed by the timecourse analyses is consistent with various behavioral and physiological studies in individuals with ADs (Carleton, 2012; Grillon et al., 2017; Holaway et al., 2006; Nelson & Shankman, 2011; Waters et al., 2008; Yook et al., 2010). We note that the uncertainty-related effects were selective to the timecourse analyses, highlighting sustained corrugator activity in anxious individuals during prolonged threat exposure. These results suggest that paradigms enabling an assessment of reactivity over time may be particularly informative in understanding altered physiological processes in individuals with pathological anxiety. Previous studies using skin conductance and eye-blink startle to assess responses to the repeated presentation of negatively valenced stimuli have demonstrated decreased habituation in anxious individuals (Campbell et al., 2013; Eckman & Shean, 1997; Jackson et al., 2017; Lader & Wing, 1964; Watts, 1975). Similarly, our findings demonstrate AD-related sustained physiological arousal to the repeated presentation of threat stimuli; however, only during conditions of uncertainty. Additionally, the current data demonstrate a similar uncertainty-related modulation of the corrugator response in subthreshold-AD girls, adding further support for the concept that even subthreshold levels of anxiety may elicit pathophysiological symptoms shared with clinical levels of AD that are distinct from healthy controls.

ADs tend to be chronic and lifelong, with a considerable number of individuals having onset during childhood. The current data demonstrate that anxiety-related physiological alterations can be detected when children are initially experiencing pathological anxiety. Because human studies suggest that emotion related corrugator activity is associated with amygdala activation (Heller et al., 2011, 2014) and primate studies point to increased early-life amygdala activity as a component of pathological anxiety (Fox et al., 2015) it is reasonable to consider that the current findings may reflect fundamental elements of the forerunners of ADs.

While facial EMG research has an extensive history in the study of emotional expression, it holds promising relevance for therapeutically oriented approaches to understanding pathophysiology. For example, a study found that when participants imagined sad and negative situations, corrugator activity was greater in depressed relative to non-depressed individuals (Schwartz et al., 1976). Based on the idea that facial muscle activity may influence the somatic perception of emotional states (Darwin, 1872; James, 1890), facial muscles have been an interesting clinical intervention target for the treatment of depression in recent years (Finzi & Rosenthal, 2016; Hennenlotter et al., 2009). Specifically, clinical trials that have used botulinum toxin A injections to immobilize facial muscles associated with sad and melancholic expressions, such as the corrugator supercilii, have shown to reduce symptoms in individuals with major depression (Finzi & Rosenthal, 2014; Magid et al., 2014; Wollmer et al., 2012). While the efficacy of this treatment is still in its early stages, these promising advancements may provide a framework in which our current findings could be relevant for utilizing the corrugator supercilii as a suitable intervention target for pathological anxiety.

In conclusion, our study highlights several new contributions for understanding the physiological correlates of threat and uncertainty processing in pathological anxiety. From a methodological standpoint, noninvasive collection of corrugator EMG is effective in capturing valence-modulated changes in reactive magnitude measures. We also showcase a new approach in examining uncertainty-related changes on the timecourse of corrugator activity under prolonged threat. Our findings also confirm physiological alterations in response to threat and prolonged uncertainty in both girls with AD and girls with subthreshold-AD. These data further support a dimensional approach to understanding and treating pathological anxiety beyond traditional diagnostic boundaries. Future directions include examining anxiety-related corrugator alterations in more racially and ethnically diverse samples. Additionally, characterization of corrugator responses to positive stimuli in anxious individuals would provide further insights into potential alterations that link emotion processing to physiology. Our findings extend the physiological characterization of childhood pathological anxiety, bring into focus the potential importance of the corrugator EMG, and highlight the utility of analytic approaches assessing discrete physiological responses as well as their temporal dynamics.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS