The Alliance for Healthier Communities' journey to a learning health system in primary care

Funding information: Canadian Institutes of Health Research

Abstract

Introduction

The Alliance for Healthier Communities represents community-governed healthcare organizations in Ontario, Canada including Community Health Centres, which provide primary care to more disadvantaged populations.

Methods

In this experience report, we describe the Alliance's journey towards becoming a learning health system using examples for organizational culture, data and analytics, people and partnerships, client engagement, ethics and oversight, evaluation and dissemination, resources, identification and prioritization, and deliverables and impact.

Results

Many of the foundational elements for a learning health system were already in place at the Alliance including an integrated and accessible data platform. Leadership championed and embraced the movement towards a learning health system, which led to restructuring of the organization. This included role changes for data support personnel, better communication, and dissemination plans, strategies to engage clinicians and other front-line staff, restructuring of committees for more collaborative planning and prioritization of quality improvement and research initiatives, and the development of a new Practice-Based Learning Network for more opportunities to use the data for research and evaluation.

Conclusions

Next steps will focus on continued clinical engagement and partnerships as well as ongoing reflection on the transition and success of the learning health system work.

1 INTRODUCTION

A learning health system is a healthcare organization with a culture of health system improvement where rapid analyses of internal data are integrated with existing evidence to produce locally relevant knowledge that is put into practice.1, 2 This concept was first identified by the Institute of Medicine in 2007 and has been gaining traction across the world,1 particularly among integrated health systems in the United States.3-8 However, there are no documented learning health systems in North America focusing solely on primary care.9 There are unique considerations for learning health systems within primary care compared to other healthcare settings. For instance, the scope of primary care is much broader, focuses on mostly preventative care, and spans the life course from infancy to elderly. This means that there is a large range of data on different conditions, and that the data are captured longitudinally across an individual's lifespan.10, 11

In Ontario—Canada's most populous province with over 14 million residents—primary care is covered under the provincial healthcare plan. The Alliance for Healthier Communities (ie, the Alliance) supports 109 community-governed primary healthcare organizations in Ontario including Community Health Centres (CHCs), Aboriginal Health Access Centres, Community Family Health Teams and Nurse Practitioner Led Clinics.12 Each of these organizations include salaried physicians who work alongside other health professionals to provide preventative care and social services, in addition to treating illnesses, for complex and higher risk individuals.12 Each member organization provides care for patients either based on a geographic need, or a social need such as populations experiencing homelessness, or with a large proportion of newcomers, Indigenous people, or primarily French-speaking populations. Patients receive ongoing, team-based primary care at an individual organization.

The Alliance is committed to advancing health equity and recognizes that access to the highest attainable health standard is a fundamental right.13 To help achieve this, the Alliance members developed a Model of Health and Wellbeing as a roadmap for service delivery,14 and strategically decided to operate and make decisions as a unified sector in 2009. This decision led to greater standardization across the organizations with common EMR standards (including the use of a standard coding nomenclature such as International Classification for Diseases), a shared data platform, common performance measures for clinical and administrative targets, and a governing decision-making committee. Until recently, the Alliance has focused more on data collection and less on using data to inform meaningful improvements in care. The Alliance is now shifting their focus and restructuring the organization as a learning health system to ensure the highest level of care and health equity is achieved through more evidence-informed decisions, ongoing quality improvement and shared learning.

The purpose of this article is to describe the process of the first province-wide learning health system for an entire primary care model in Ontario, Canada. We document the Alliance's journey towards becoming a learning health system and anticipate that other healthcare organizations and sectors may find this information useful.

2 THE ALLIANCE AS A LEARNING HEALTH SYSTEM

2.1 Overview

Using a framework adapted from Psek (2015), we describe how the Alliance meets the nine criteria for a learning health system (criteria defined in Appendix A).3

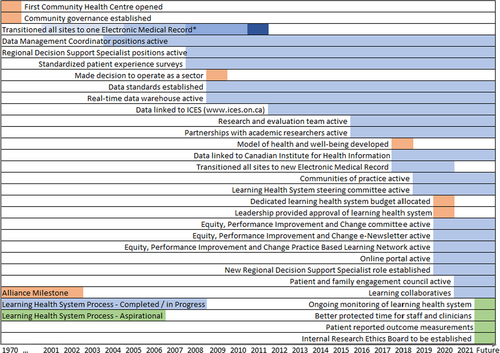

We provide a detailed timeline showing key milestones towards the Alliance becoming a learning health system starting with community governance in the 1970s, the decision to operate as a sector in 2009 and leadership approval of the learning health system in 2020, along with all the contributing processes as described below in this paper (Figure 1). This figure demonstrates the extensive time and planning that is necessary for the development of a learning health system.

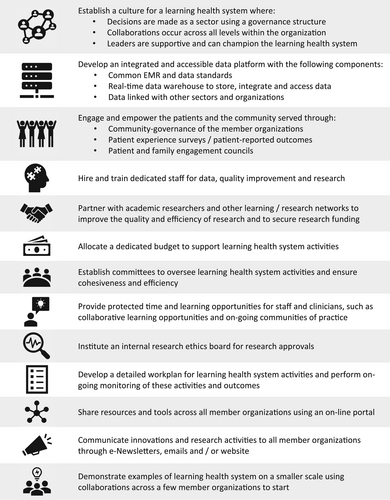

Figure 2 is a more generalizable outline of the actions recommended for the development and functioning of a learning health system based on the Alliance's experience that other healthcare organizations and sectors may find useful.

2.2 Organizational culture

The Alliance's organisational culture provides a foundation well-suited for a learning health system. Their vision is “the best possible health and wellbeing for everyone living in Ontario” accomplished through “transformative change to improve the health and wellbeing of people and communities facing barriers to health”.15

The Alliance has grown organically from a collaboration between like-minded healthcare providers sharing a common goal to decision making as a sector. The Alliance governance structure consists of three main committees of Executive Leaders who have been delegated to manage projects and make decisions for the sector. Ad hoc working groups are frequently established to ensure engagement with clinicians and other interprofessional providers and administrators. Executive Leader meetings are held every 6 months to provide system-level updates, formally endorse the work, and to establish priorities. This structure has been created to ensure that Executive Leaders, staff, and clinicians of each member organization are included in decision making and priority setting. There is a collaborative effort among all team members to work together and identify learning opportunities that bring about change and to measure the effectiveness of changes. Member organizations are encouraged to collaborate with peers through communities of practice and to foster a culture of curiosity and inquiry in the workplace.

2.3 Data and analytics

The foundation for a successful learning health system is an integrated and accessible data platform, which the Alliance has already established through their Information Management Strategy. All member organizations paid to develop and then implement a common information system and performance measurement framework. This includes access to the EMR, data warehouse, other tools, and technical support for all member organizations to collect and maintain high-quality data (including standardized data templates within the EMR), as well as analysing their data and sharing findings. The majority of Alliance members have transitioned to a common EMR (PS Suite16) and all members follow mandatory data standards, with almost 90% alignment with the Canadian Institute for Health Information's EMR standards list,17 including the use of standardized coding for conditions based on International Classification for Diseases, and other standards for equity and socioeconomic data. These standards allow the data to be collated across the Alliance through a data warehouse that provides near real-time access. A data governance framework allows each Alliance member to securely access client data, so queries can be made to answer clinical questions and conduct quality improvement initiatives or program planning. As for performance measurement, there are targeted benchmarks for objective clinical measures such as cancer screening, chronic disease management, and amount of care delivered. There are also subjective measures including patient reported experience outcomes. These performance measures were identified through a collective decision-making process.

A learning health system relies not only on internal data but also research using other data sources. The data collected within the Alliance, including all services provided by interprofessional team members and client sociodemographic data (age, gender identity, education level, etc.), are routinely linked with administrative province-wide data (includes hospital, emergency room, and other healthcare databases). There are formalized agreements with provincial and National health data organizations that allow for data linkage and participation in population-based research, while accounting for privacy and other research policies.18, 19 Some examples of using real-time data to inform service delivery and improve care within the Alliance is included in Table 1.

| Initiative | Description |

|---|---|

| Primary care dashboard | The primary care dashboard uses data from the EMR to inform decisions at the point of care, including cancer screening rates, screening and management for diabetes, influenza vaccines, and complex patients. Clinicians can view patient lists and access patient level data to contact individuals. Other staff not directly involved in the patients' care can only access group level data, such as the aggregate number of people due for their influenza vaccine. Finally, the dashboard can allow providers to make comparisons across different member organizations at an aggregate level for benchmarking purposes. The primary care dashboard was developed by clinicians and leadership through a conference workshop and based on measures prioritized through a DELPHI panel. |

| Learning collaborative on reducing the cancer screening backlog | There are 20 member organizations involved in the learning collaborative focused on decreasing the cancer screening backlog due to the COVID-19 pandemic. Using data from the Alliance data warehouse, a monthly tailored report is generated and provided to each participating organization showing equity-stratified risk data for who is due for cancer screening (stratified by determinants of health such as income, race, sexuality). Run charts are created to see improvements over time. Each member organization then uses this information to tailor interventions, create change ideas, work with a quality improvement coach, and monitor change and improvements in cancer screening over time. Evaluation of this learning collaborative is iterative and includes reviewing feedback from participating measures to continually improve the process. |

| Learning collaborative on improving socioeconomic and race data quality | This learning collaborative is currently in the planning phase. Every fiscal quarter, data quality reports will be provided to all organizations that describe the completeness of standardized socioeconomic and race data, and how data completeness is improving over time. The teams that take part in the learning collaborative will use these data reports and apply quality improvement methods, including benchmarking and coaching throughout their data completeness journey. |

2.4 People and partnerships

There are key individuals who championed the learning health system initiative, one person being the Director of Research and Evaluation (JR) who gained the trust and respect from all levels across the Alliance. Other key individuals are the Alliance's CEO and Alliance Member Executive Leaders, who jointly advocated for the learning health system and helped champion this across the Alliance to secure resources to move this forward.

In November 2020, the Alliance's Practice-Based Learning Network (PBLN) was established - a group of clinicians working together to explore challenges, develop and share innovations, measure effectiveness, and drive improvement through research and quality improvement. The purpose of this PBLN is to engage more clinicians and increase their curiosity and ability to use their data to inform care. The Alliance's PBLN, is also now part of a greater network of Ontario's PBLNs called POPLAR (Primary Care Ontario Practice-Based Learning and Research Network)20 that includes six other PBLNs that are associated with Departments of Family Medicine. Joining this network of networks, allows the Alliance's data to be linked to a provincial repository of primary care EMR data, which can be used for research and evidence-based decision making. One example project through POPLAR is a deprescribing learning collaborative for older individuals experiencing polypharmacy.21

A learning health system must also be driven by the clinicians and front-line staff who care for the clients; however, low clinician participation in the learning health system has been a challenge. The Alliance will support engagement in their PBLN by training clinicians on how to ask research and quality improvement questions, gather meaningful data, and conduct evaluations to inform improvement or learning. One method to help increase participation is having peer champions who are modelling how they have used their data in practice to help inform care. Furthermore, research partners through the PBLN have a community engagement group who are reaching out to clinicians to help increase participation. All interactions with clinicians and staff are focused on ensuring that research questions and priorities are meaningful and result in practice improvements or better health outcomes.

The Alliance has dedicated staff focusing on data quality and evaluation who help support the learning health system, specifically four Regional Decision Support Specialists. Their original role was to facilitate evidence-based planning and decision making, particularly helping Alliance members to meet their accountability responsibilities (ie, meeting specific financial and clinical targets to maintain government funding). This role has been redesigned, allowing these individuals to now work more closely with Alliance members to focus on quality improvement priorities. This includes ongoing data standardization and completeness, better understanding of the EMR workflow, and developing tailored reports with recommendations and support for improvement. For example, the Regional Decision Support Specialists are involved in the learning collaborative initiatives described in Table 1, where they are responsible for generating and disseminating tailored cancer screening reports, data quality reports, run charts, and providing individual quality improvement coaching to the teams. Through this process, there has been an increased need for training and all four individuals in this role have received Six Sigma Green Belt certification for quality improvement.22

In regards to external partners, some collaborations with academic researchers had already existed prior to 2016, but more official collaborations focusing on learning health systems with MZ began in 2016. Over the past 5 years, momentum for learning health system research within the Alliance has grown. For example, one on-going project is using artificial intelligence to identify Alliance clients who are at risk for certain high-priority chronic diseases.

2.5 Client (patient) engagement

All Alliance members are community governed and have an obligation to ensure that clients and communities direct and plan service delivery, are involved in governance, and that research leads to improvements in outcomes or service delivery. On-going training and accreditation are conducted to ensure that board membership and decisions are community driven.23

Clients, their caregivers, and broader community members will be involved throughout the learning cycle to identify what matters most to them and share their experiences both within and outside the healthcare system. Currently, Alliance members are encouraged to conduct client experience surveys to help understand how well programs and services are working from the client perspective. To expand on this, the Alliance has developed a common tool to more consistently measure clients' experiences using a provincial framework,24, 25 and will be evaluating a patient reporting outcome measures tool for use across the sector (ie, the EQ-5D, which allows patients to self report on their health across five dimensions).26

A Client Engagement Council is being created to inform the work of the PBLN. The goal of this council is to ensure that research and quality improvement priorities and findings are meaningful and to have a group of client partners that collaborate on research projects.

2.6 Ethics and oversight

The Alliance has a robust committee structure that ensures productivity and prioritization of learning activities. The Information Management Committee is responsible for advancing and maintaining the foundation of the learning health system by protecting data privacy, ensuring data quality and standards, and providing technical support for the EMR and the data warehouse.

A Learning Health System Steering Committee was established in November 2019 with broad representation from across the Alliance as well as academic researchers. The purpose of this committee was to guide the work for the learning health system and create an action plan. This led to a Hackathon in January 2020 where a broad group came together to create a visualization (ie, a driver diagram) demonstrating the work to be done by the learning health system.27

Following the Hackathon and other subsequent planning meetings, a long-standing committee responsible for all performance management responsibilities (the Performance Management Committee) was renamed to the Equity, Performance Improvement, and Change (EPIC) committee and restructured to focus more on improvement and learning. EPIC is an Executive-leader-led committee that will provide guidance to the learning health system by supporting high-impact quality improvement and learning activities.

University research ethics boards are currently used to review and approve research studies conducted within the Alliance. As part of the learning health system redesign, the Alliance is considering the development of their own research ethics committee to provide a more efficient approach to research ethics approvals.

2.7 Evaluation and dissemination

The EPIC committee created a high-level workplan to guide the learning health system efforts over the next year, which follows the Alliance's Model of Health and Wellbeing and Evaluation Framework (Table 2).14, 28 The Alliance is also developing a comprehensive learning health system evaluation plan to better understand the successes and challenges of the redesign. This includes performance and process measures that will be presented to EPIC as a scorecard, based on a maturity grid for learning health systems.32 The findings from this ongoing evaluation will be used to improve components of the learning health system and lessons learned will be shared with relevant stakeholders.

| Objective | Expected learning health system deliverable |

|---|---|

| Improve completeness of relevant equity and race data | A centre-specific data-quality report provided every other month to the Alliance member organizations (as described in Table 1) |

| Enhance capacity for local quality improvement | A quality improvement training strategy for Alliance members, including training through the College of Family Physicians of Canada's Practice Improvement Initiative29 |

| Support population health planning in Ontario Health Teams | A report on mental health care provided to centres to proactively understand the characteristics of unattached people and ensure that they can access care at local member organizations Advocate for population data to include social determinants of health to better understand disparities in health outcomes and health care utilization |

| Improve access to care | Support learning collaboratives for priority areas: |

| Foster a culture of curiosity and inquiry that leads to new knowledge | Support and provide guidance to the Alliance's PBLN Peer mentors to help increase curiosity and provide examples for how to use data to improve care |

| Improve quality of care | Reduce polypharmacy and associated adverse events for older people through a deprescribing learning collaborative21 Improve screening rates for diabetic retinopathy for people with diabetes by using a case finding algorithm through administrative data31 |

As described in Table 1, a series of learning collaboratives were launched in Fall 2021, which use quality improvement methods to help a group of peers work together to solve common problems. The first learning collaborative focuses on reducing the cancer screening backlog issue, which many Alliance members are experiencing due to the COVID-19 pandemic. There are also professional learning events and regular lunch and learns. These lunch and learns are generally led by staff or clinicians, and many have had over 300 attendees. For example, during the beginning of the COVID-19 pandemic, topics included how to provide care for people in congregate living, harm reduction, and how to create platforms for virtual care delivery. Communities of practice are also underway, and will focus on shared learning, best practices, and peer support across the Alliance members.

To ensure broad communication of the learning health system, research updates, innovative practices, and opportunities to be involved, a monthly EPIC newsletter was launched in November 2020.33 This is broadly shared internally with Alliance members and externally with stakeholders and the public. The Alliance's website also features a description of the learning health system.34

To disseminate learnings across the membership, the Alliance has developed an on-line portal where key documents and tools can be securely and conveniently accessed by everyone across the Alliance. Training on using this new portal has been provided to ensure equitable access to all resources.

2.8 Resources

Funding is necessary to both develop and sustain a learning health system. A financial plan was drafted and approved, which included reallocation of resources needed to operationalize the learning health system without the need for any additional costs to Alliance members. Funding for specific research projects will come from academic researchers' grants.

A challenge for many staff and clinicians to participate in research or learning initiatives is the time commitment. The Alliance is developing mechanisms to ensure staff and clinicians have the time to devote towards the learning health system initiatives. This includes Executive Leaders' support and endorsement for freeing up staff time to participate in research and other learning initiatives. Professional credits are being sought for all learning health system activities to ensure that clinicians see the value and their participation is recognized.

2.9 Identification and prioritization

Through the PBLN, clinicians and front-line staff are driving priority learning initiatives from the bottom-up. They identified several priority areas which were then brought to the EPIC committee. This committee presented all topics to the Executive Leaders network and selected key priority areas for the year. Initial learning collaboratives and communities of practice (referenced in the Evaluation and Dissemination section) were identified based on the committee's selection. In addition, Executive Leaders are now suggesting ad hoc communities of practice, which are being used as a vehicle to share learnings and leverage expertise. An example of this is the recently formed community of practice on post-pandemic planning.

2.10 Deliverables and impact

Although impact from the Alliance's recent shift towards an operational learning health system has not yet been evaluated, collaborations among Alliance members demonstrate how a learning health system across the Alliance could function on a smaller scale. A group of Alliance members in Toronto have formed a partnership called the West End Collaborative with a shared goal of better quality of care by setting and meeting specific benchmarks. For example, focusing on improving cancer screening rates and ensuring equity across different marginalized groups in receiving cancer screening.35

Learnings and innovations will be shared through mechanisms previously described including the EPIC newsletter, lunch and learns, and the on-line portal. The EPIC committee will be responsible for deciding on successful initiatives to scale up across the organization.

3 CONCLUSIONS

The journey started with a few key champions and external collaborators, adapting the learning health system approach to be amenable to the Alliance, and iteratively testing it in workshops and in consultation with several different committees. The process of co-creating the Alliance learning health system included the active involvement of over 70 people.

This approach was then given a tentative form and plan and promoted within the decision structures of the Alliance. The recognition that many of the key components of a learning health system were already in place led to enthusiasm for this bold new vision among Executive Leaders who sponsored the proposals for restructuring the organization to better function as a learning health system. These proposals have been accepted by all decision-making structures in the Alliance and their implementation has been incorporated into the current annual plan.

As with all journeys, there is still a lot to explore and learn. Next steps will focus on continued clinician, staff, and community engagement and partnerships, as well as ongoing evaluation of the success of the learning health system work.

Abbreviations

-

- Alliance

-

- Alliance for Healthier Communities

-

- CHCs

-

- Community Health Centres

-

- EMR

-

- Electronic medical record

-

- EPIC

-

- Equity, Performance Improvement and Change

-

- PBLN

-

- Practice-Based Learning Network

AUTHORS' CONTRIBUTIONS

Jennifer Rayner and Merrick Zwarenstein were responsible for conception of manuscript. Danielle M. Nash drafted the initial manuscript, which was reviewed, revised, and approved by all authors.

FUNDING INFORMATION

Danielle M. Nash's training is supported by a Canadian Institutes of Health Research Post-Doctoral Fellowship.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST

Jennifer Rayner is an employee of the Alliance for Healthier Communities. No other authors have any competing interests.

INFORMED CONSENT

No human participants or human data have been used in this study.

APPENDIX A: Components of a learning health system (adapted from Psek, 2015)3

| Component | Definition |

|---|---|

| Organizational culture | Organizational culture (values, standards) and structures required to implement and sustain a learning health system. |

| Data and analytics | Infrastructure and processes to enable high-quality and real-time data capture and analysis for learning activities. |

| People and partnerships | Staff and partners required to initiate and drive learning activities. |

| Client (patient) engagement | Clients (patients and their family members) as key partners required to shape the direction and priorities of learning activities that impact the quality of care they receive. |

| Ethics and oversight | Development of new processes and frameworks for research approvals and clinical care to ensure cohesiveness and efficiency in approvals for learning initiatives. |

| Evaluation and dissemination | Development of methodological plans to implement, evaluate, and disseminate learning activities. |

| Resources | Resources needed to initiate and sustain learning activities including funding and protected time of staff/ clinicians. |

| Identification and prioritization | Identification and prioritization process for new learning activities in alignment with strategic goals of the organization. |

| Deliverables and impact | Examples of successful learning activities that have demonstrated an improvement, and mechanisms to scale these up across the organization. |

Open Research

DATA AVAILABILITY STATEMENT

All data generated or analysed during this study are included in this published article.