The Global Experience of Laryngeal Transplantation: Series of Eleven Patients in Three Continents

The authors have no funding, financial relationships, or conflicts of interest to disclose.

Abstract

Background

The loss of laryngeal function affects breathing, swallowing, and voice, thus severely compromises quality of life. Laryngeal transplantation has long been suggested as a solution for selected highly affected patients with complete laryngeal function loss.

Objective

To obtain insights regarding the advantages, weaknesses, and limitations of this procedure and facilitate future advances, we collected uniform data from all known laryngeal transplants reported internationally.

Methodology

A case series. Patients were enrolled retrospectively by each institutional hospital or clinic. Eleven patients with complete loss of laryngeal function undergoing total laryngeal transplantation between 1998 and 2018 were recruited.

Results

After a minimum of 24 months follow-up, three patients had died (27%), and there were two graft explants in survivors, one total and one partial, due to chronic rejection. In the remaining cases, voice was functional in 62.5% and 50% achieved decannulation. Swallowing was initially restricted, but only one patient was gastrostomy-dependent by 6 months and all had normal or near-normal swallowing by the end of year two after transplantation. Median follow-up was 73 months. Functional (voice, swallowing, airway) recovery peaked between 12 and 24 months.

Conclusions

Laryngeal transplantation is a complex procedure with significant morbidity. Significant improvements in quality of life are possible for highly selected individuals with end-stage laryngeal disorders, including laryngeal neoplasia, but further technical and pharmacological developments are required if the technique is to be more widely applicable. An international registry should be created to provide better quality pooled data for analysis of outcomes of any future laryngeal transplants.

Level of Evidence

4 Laryngoscope, 134:4313–4320, 2024

INTRODUCTION

Loss of laryngeal function impairs vital human social and functional abilities, especially communication, respiration, and swallowing.1 Currently, no comprehensive, holistic therapeutic approach addresses the three main laryngeal functions. Various solutions have been developed to overcome the disabilities of alaryngeal people, such as electrolarynx, the development of tracheoesophageal speech, laryngeal pacemakers, and various designs of stoma. A non-vascularized laryngeal tissue transplant was first attempted in 1969 in a 62-year-old man with laryngeal cancer,2, 3 but it was not until 1998 that the first fully vascularized laryngeal transplant (included here) was performed. These and subsequent experiences were the stepping stones for further laryngeal transplants over the last 25 years.4, 5 As with other composite vascularized allotransplants, such as the face and limb, laryngeal transplantation faces many complex challenges.6-8 These include preoperative candidate selection, procedural technical difficulties (vascular anastomosis, pharynx augmentation, and neural anastomosis), and posttransplant management such as induction, immunosuppression regimen, rejection, opportunistic infection prophylaxis, and standardized outcome measures. There are also ethical concerns related to the risks associated with lifelong immunosuppression for persons with a non-life-threatening problem. We present a case series of all known (to our knowledge) reported and unreported cases of total laryngeal transplantation, from four centers in three continents. Additional transplants involving parts of the larynx were identified, including 10 partial laryngeal plus partial tracheal, 2 partial laryngeal alone, and 4 tracheal transplants encompassing part/all cricoid (one reported last year in New York9). Here, however, we restrict our report to a more homogenous group of total laryngeal transplants performed with the objective of understanding outcomes and laryngeal functional recovery.

METHODS

Patient Recruitment

All patients and donor families provided written informed consent for laryngeal transplantation, and each was approved by clinical ethics committees in each institution according to local and national guidelines. An expert multidisciplinary group evaluated every case and preoperative processes for transplantation individually. Table I summarizes patients' medical records. Extended details, including pre-transplantation variables and case histories, are available in an online supplemental appendix. Potential donors were matched with recipients by Human Leukocyte Antigens (HLA) histocompatibility, sex, and age. A minimum of two experienced head and neck or thoracic surgeons performed all retrieval and implant procedures, with defined roles allocated to all surgical and other essential staff. Written consent was obtained for each study participant. Study approval was granted by each institution's ethics committee and/or review board. The present manuscript was written following the case report checklist of the EQUATOR guidelines.

| A. Demographic Characteristics and Preoperative Status | B. Other Procedures | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Age† | 38 (IQR 30–52) | Prior radiation | |

| Yes | 3 (27.2%) | ||

| Sex, n (%) | |||

| Female | 3 (27.2%) | Prior immunosuppression | |

| Male | 8 (72.8% | Yes | 1 (9%) |

| C. Complications | |||

| Ethnicity, n (%) | None | 1 (9%) | |

| Black | 1 (9%) | Fistula | 1 (9%) |

| Hispanic | 5 (45.4%) | Dehiscence | 1 (9%) |

| White | 5 (45.4%) | Hematoma | 1 (9%) |

| Pneumonia | 1 (9%) | ||

| Previous airway conditions | Sepsis | 2 (18.2%) | |

| Radiation | 2 (18.2%) | Restenosis | 2 (18.2%) |

| External trauma (larynx and pharynx) | 4 (36.4%) | Pulmonary embolism | 1 (9%) |

| Previous airway surgery | 3 (27.2%) | Death | 3 (27.2%) |

| Neoplasia* | 3 (27.2%) | Vocal cord paralysis | 2 (18.2%) |

| Radiation and neoplasia | 1 (9%) | Rejection | 1 (9%) |

| Infection | 4 (36.4%) | Hypertension | 2 (18.2%) |

| Endotracheal intubation | 1 (9%) | ||

| Burn | 2 (18.2%) | Immediate (24 h) | |

| None | 8 (72.8%) | ||

| Performance status | Death | 1 (9%) | |

| Absent | 2 (18.2%) | AKI | 1 (9%) |

| Poor | 9 (81.9%) | Hypertension | 2 (18.2%) |

| Prior intervention | Early (<30 days) | ||

| None | 1 (9%) | None | 5 (45.4%) |

| Endoscopic laryngeal restoration | 1 (9%) | Anastomotic dehiscence | 1 (9%) |

| Laryngotracheal resection | 4 (36.4%) | Restenosis | 1 (9%) |

| T-tube insertion | 1 (9%) | Massive bleeding | 1 (9%) |

| Laryngoplasty | 2 (18.2%) | Sepsis | 1 (9%) |

| Colon transposition for thoracic esophagus reconstruction | 3 (27.2%) | Aspiration | 1 (9%) |

| Number of previous interventions† | 1.2 (1–1.75) | Late (>30 days) | |

| None | 3 (27.2%) | ||

| Comorbidities | Tracheocutaneous fistula | 1 (9%) | |

| None | 5 (45.4%) | Restenosis for granuloma | 2 (18.2%) |

| Diabetes mellitus | 1 (9%) | Median (IR)† | |

| Arterial hypertension | 2 (18.2%) | ||

| Autoimmune disease | 1 (9%) | ||

| Major surgery | 1 (9%) | ||

| Sepsis | 2 (18.2%) | ||

| Previous transplantation | 1 (9%) | ||

| Number of comorbidities† | 1 (0–1.5) | ||

- * Hodgkin's lymphoma and squamous cell cancer of the larynx (2).

- † Median and interquartile range.

Inclusion Criteria

All patients were evaluated by a multidisciplinary team before transplantation. After extensive discussion of indications, risks, benefits, and ethical concerns, full laryngeal transplant was agreed by all the patients in an attempt to restore lost laryngeal functions. The definition of full laryngeal transplant in this study was that of complete larynx framework revascularized organ transfer including vocal cords. During the pretransplant examination, patients were screened for malignancy, and cardiovascular disease stratification was performed in preparation for lengthy procedure times.

Transplantation Procedures

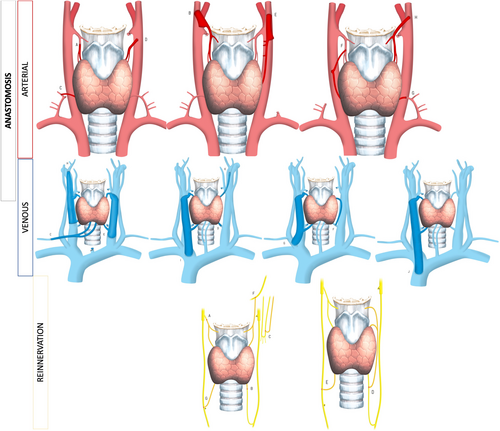

The donor block included larynx and trachea in 55% of the cases, with the addition of pharynx and/or esophagus in the remainder. Revascularization was based on (donor) superior laryngeal arteries, with the use of inferior thyroid and transverse cervical arteries as backup if the former were not accessible. Recipient arteries were variable depending on previous surgery/trauma and surgical teams' preference: thyroid, transverse cervical, subclavian, or external carotid arteries, with the latter used preferentially in Colombia (Fig. 1A–C). The selection of venous drainage was more variable, and the internal jugular (11 of 17 anastomoses; Fig. 1D–F) was the most common recipient vein. Only one venous anastomosis was performed in four cases (Tables S1 and S2). Nerves were repaired in the majority of cases, with 9/11 using nonselective direct recurrent laryngeal nerve repair and 10/11 directly repairing the superior laryngeal nerves. Figure 1G–I describes nerve repairs. There was one attempt at unilateral functional reinnervation (split phrenic nerve-to-intralaryngeal abductor branch of recurrent nerve). All patients were managed postoperatively in the intensive care unit.

Immunosuppression

All patients received immunosuppression. One had prior immunosuppression due to kidney transplantation. Six patients received preoperative induction immunosuppression: mycophenolate mofetil, prednisone, and tacrolimus (three); anti-thymocyte globulin, methylprednisolone, and mycophenolate mofetil (one); daclizumab (one); and anti-thymocyte globulin (one). Five patients received adjuvant immunosuppression therapy with steroids (four), and one patient received mesenchymal stem cells after the reperfusion period. After reperfusion, most (seven) people received tacrolimus, mycophenolate, and prednisone. The patient from Cleveland received cyclosporine, azathioprine, and methylprednisolone, whereas the patient from UC Davis received tacrolimus and mycophenolate mofetil. Patients from Colombia received cyclosporine, mycophenolate, and prednisone or tacrolimus and sirolimus. Maintenance immunosuppression comprised tacrolimus, mycophenolate, and prednisone with tacrolimus in seven patients; mycophenolate in two; cyclosporine, mycophenolate, and prednisone in one; and tacrolimus and sirolimus in the last patient. One patient voluntarily ceased immunosuppression following partial graft excision at 36 months.

In the absence of standard criteria, rejection in this series was evaluated subjectively by the development of new symptoms of dyspnea, dysphagia, and dysphonia and by endoscopic findings of inflammation and edema. Stroboscopy and laryngeal electromyography were used to improve the objectivity of rejection measurement in the patient from Cleveland.10 Follow-up after hospital discharge was monthly for 6 months, followed by every 3 months with endoscopy and yearly biopsy for graft inspection, in addition to laboratory medication levels for monitoring immunosuppression therapy until the end of the follow-up period. During the transplant procedure and in the posttransplant period antibacterial, antimycotic and antiviral medication were provided for all patients.

RESULTS

Patients

Transplants reported here were performed between 1998 and 2022 in the United States (two), Colombia (five), and Poland (four). Table I shows the demographic characteristics. Causes of laryngeal failure were trauma, including iatrogenic, infection, and cancer treatment. Four patients presented with infection after therapeutic radiation for cancer, whereas another four patients suffered from severe laryngeal and pharyngeal trauma, two patients swallowed corrosives and presented chemical injury, and one patient developed severe laryngeal dysfunction after traumatic endotracheal intubation. Ten patients had previous surgery. Multidisciplinary teams considered all conventional options in every case, including seeking external independent clinical opinion, and adopted simpler treatments wherever possible. However, where there was deemed to be no ideal or low morbidity solution, any remaining conventional options were presented alongside laryngeal transplantation to provide a fully informed choice. Table S1 presents operative details. The average length of stay after the procedure was 59 days (IR 27–90 days; see Table S1).

Complications were relatively frequent. Three patients experienced early complications (within 24 h), one with fatal pulmonary embolism and another was successfully treated for bilateral pneumothorax. In the perioperative period (first 30 days postoperatively), six patients variously experienced stenosis, anastomotic dehiscence, massive bleeding, aspiration pneumonia, and sepsis, whereas eight patients suffered late (>30 days) complications, mainly stenosis. Three patients died within 20 years of reporting from pulmonary embolus (one, postoperative day 1) and sepsis (two, at 6 and 18 months), though all three had viable grafts at the time of death. Three had signs (see above) of early rejection, whereas four patients had an average of 1.6 episodes of presumed chronic rejection during the study period (IR 0–1), with the first event occurring at a mean of 66 months (IR 39–81) and two undergoing partial (one, 18 months) and total (one, 168 months) graft excision. Additionally, four patients presented structural changes in the allograft, possibly relating to chronic rejection, consisting of persistent swelling, laryngeal constriction, atrophy of the epiglottis, and mild pharyngeal contracture.

Table II shows the functional outcomes for eight patients with intact grafts reaching at least 1 year of follow-up. A first competent swallow was observed at a mean of 5 months of follow-up (IR 2–7), and regular oral intake was achieved at approximately 8 months (IR 2–16), although limitations remained in most, with only two managing a full oral diet at 1 year, rising to four of the eight patients reaching 2 years of follow-up (Table II and Figure S1). Early swallowing was achieved in the majority of the cohort, possibly due to the inclusion of between 80% or more of the pharynx in seven patients. One benefited from balloon dilatation of pharyngeal stricture and one from endoscopic esophagus dilatation. Six of eight patients had a voice described as at least “satisfactory” at 1 and 2 years (Figure S2).

| Outcomes | Preoperative Measurements (n = 11) | First-Month (n = 10) | Sixth-Month (n = 9) | First Year (n = 8) | Second Year (n = 8) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Airway patency | |||||

| Absent | 11 (100%) | 9 (90%) | 7 (77.7%) | 5 (62.5%) | 2 (12.5%) |

| Poor | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Satisfactory | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 (12.5%) | 0 |

| Good | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 2 (12.5%) |

| Excellent | 0 | 1 (10%) | 2 (22.2%) | 2 (25%) | 4 (37.5%) |

| Voice | |||||

| Absent | 9 (81.9%) | 4 (40%) | 1 (11.1%) | 0 | 1 (12.5%) |

| Poor | 2 (18%) | 2 (20%) | 2 (22.2%) | 2 (25%) | 1 (12.5%) |

| Satisfactory | 0 | 3 (30%) | 4 (44.4%) | 2 (25%) | 3 (37.5%) |

| Good | 0 | 1 (10%) | 1 (11.1%) | 3 (37.5%) | 1 (12.5%) |

| Excellent | 0 | 0 | 1 (11.1%) | 1 (12.5%) | 2 (25%) |

| Swallowing | |||||

| Gastrostomy only | 4 (36.4%) | 7 (70%) | 1 (11.1%) | 0 | 0 |

| Highly restricted oral intake | 4 (36.4%) | 0 | 2 (22.2%) | 2 (25%) | 1 (12.5%) |

| Partial oral intake | 1 (9.0%) | 3 (30%) | 4 (50%) | 4 (50%) | 3 (37.5%) |

| Fully oral intake | 2 (18.2%) | 0 | 2 (22.2%) | 2 (25%) | 4 (50%) |

Preoperatively, 9 of the 11 patients were aphonic, and the other two had voices that were “poor.” At 1 month, six of the nine survivors had useable voices, and at 6 months, seven of eight (Table II and Figure S2). Overall, stable phonation, as measured by this subjective scale, was obtained after approximately 8 months of follow-up (IR 2–16). Motor reinnervation was not objectively evaluated in the majority of the cohort. However, two patients were evaluated by electromyography, evidencing reinnervation. The technique in these two patients involved end-to-end repair of superior laryngeal nerves (both), end-to-side joining of donor recurrent nerve and phrenic nerve trunk (one patient, one side), and end-to-end repair of recurrent nerves (one patient unilateral, one bilateral). Despite the attempt at selective reinnervation using phrenic drive in one with early signs of useful abduction on that side, both patients had long-term bilateral synkinesis with intrinsic laryngeal muscle tone but no useful abduction.

Laryngeal airway patency outcomes were good, with five patients at 1 year and only two patients at 2 years retaining a form of tracheal stoma (Table II and Figures S3 and S4). For those decannulated (4/8 recipients reaching 2 years follow up), this occurred at a mean of 7 months (IQR 0.87–13.75). Further procedures to maintain the airway were performed in several patients including cordotomy, arytenoidopexy, repeat tracheostomy, balloon dilatation, and stenting. Overall mean patient survival at the time of censorship was 73 months (IR 13–116). The details of individual cases are presented in Tables S2 and S3, and Figures S1–S4.

DISCUSSION

The human larynx is a composite organ with three intimately related critical functions: airway protection during swallowing, airway patency, and phonation. The loss of one or more of these functions may not be life-threatening, but severe loss of function has profound psychosocial, as well as physical morbidity.11, 12 Many people with laryngeal trauma, and most undergoing laryngectomy for “functional” (as opposed to oncologic) reasons, can be managed with conventional swallowing and voice rehabilitation techniques and/or long-term tracheostomy, with a reasonable quality of life. However, there is still a small group for whom these options are either not possible or unacceptable. A study involving 372 laryngectomies found that 75% of them would find laryngeal transplant acceptable if it did not result in significant morbidity. Most of them emphasized the desire to lose their stoma rather than regain their normal voice.6 When retaining the stoma was necessary to regain normal voice, the percentage of individuals who found laryngeal transplant acceptable decreased to 58.9%. Additionally, approximately 50% were willing to accept a graft even if it did not result in a normal voice.6 Furthermore, the study revealed a positive correlation between patient age and a positive response to laryngeal transplantation.

Ethical considerations are important with any new procedure or surgical technique. As with other composite allografts, the goal of laryngeal transplantation is to improve the quality, rather than the length of life, although it has been argued that candidates may be considered as already suffering from “social death.”8 Ethically, it is also critical to record, evaluate, and publish the outcomes of developing interventions to properly determine their real benefits and place in present and future health care. This article is the first attempt to present such data from all reported and known cases of laryngeal transplantation to September 2022. Patients were deemed by their treating medical teams as having no conventional suitable solution prior to consenting for transplantation. However, presenting such complex information about risks and benefits of transplantation versus any remaining conventional options provides significant practical and ethical challenges, and a standardized approach should be adopted in future. We believe that the present article provides critical data to improve such informed choice for patients in any future planned laryngeal transplants.

We found that laryngeal transplantation is technically demanding but feasible for a well-organized and trained head and neck surgical unit.13 Compared with other complex organ transplants, patient (8/11, 73%) and graft (1/11 partially lost by 2 years, one total removal at 14 years) survival rates are excellent with one patient having 168 months survival allograft, which was the longest surviving maiden transplanted organ at the time of its eventual loss.14, 15 Complications such as the stenosis of the pharynx and trachea were reported but manageable by conventional dilatation and other techniques. Therefore, technical feasibility and reasonable safety are supported. Allotransplantation of non-vital organs aims to restore function, with a useful, tracheostomy-free airway representing the ideal outcome. The persistence of a tracheostomy was described in one report as “social death.”8 However, for several transplant recipients with tracheostomies, they reported a high quality of life. Indeed, the US patient who lost his larynx after many years said that he would happily undergo the procedure again, such were his perceived benefits of having an intact larynx. No detailed quality of life and psychological studies have been performed on this cohort to date but this is an important area for future exploration. Several patients are free from tracheostomy, speaking, and with oral nutrition, although their voices tend to be somewhat breathy and there is a residual unquantified risk of aspiration.

The overall goal of laryngeal transplantation is to provide functional recovery and improved quality of life. We found post-procedure recovery of breathing, swallowing, and voice appeared to reach acceptable levels for most recipients after 1–2 years. Nevertheless, by 2 years, four of eight patients had oral diet exclusively, three partially restricted, and only one patient had highly restricted oral intake. None had total reliance on gastrostomy feeding. Longer term studies will show whether more recovery is possible, for example, with alternate swallowing therapy regimens and technical modifications of surgical technique, such as increased pharyngeal tissue included in the graft. As well as reducing dysphagia, this may reduce the need for dilatation of pharyngoesophageal stenosis as well as the risk of postoperative anastomotic leaks. In terms of vocal outcomes, these were satisfactory, reflecting the proximity of graft vocal cords as a result of synkinesis and/or “cadaveric” positioning. All three of the tracheostomy-dependent recipients had a “good” or “excellent” voice, probably since their cords were the closest together.

Three deaths in a series of 11 patients are a potential cause for concern. We recommend rigorous thromboprophylaxis, as with any major surgery, to prevent pulmonary embolism. Likewise, close monitoring for incipient sepsis with early, vigorous therapy and microbiology specialist input, is critical, as for any group of immunosuppressed patients. However, it should be noted that 11 patients still represent a small series and that all surgical groups are on a collective learning curve. Combined long-term outcomes, tissue- and blood-banking, and data-sharing for these and all future patients should increase understanding and reduce risks, especially for these preventable causes of mortality. This process of combined data collection and learning will also be critical for better understanding, and thus to better diagnose and manage chronic rejection, which appeared to be the most common cause of graft failure and loss herein.

An important criticism of this study is the lack of standardized, validated quality-of-life outcome measures. Because of variations in outcome recording between the participating countries, we adopted a simplified common measurement scale that is subjective and lacks granularity. Critically, despite several anecdotal reports of satisfaction and high functioning, no formal measurement of psychological well-being and social functioning was undertaken. Since improvement in all of these parameters is the major goal of laryngeal transplantation, an international consensus on how and when these should be measured must be achieved. The same is true for a consensus definition of clinical and laboratory criteria for “rejection.” These aims may be best attained through an international registry, such as is already in place for other composite organ allografts.16

Core laryngeal functions depend on the position of the vocal cords. There was evidence of motor reinnervation in two patients undergoing electromyography, and possibly a third on clinical observation, whereas only two retained a permanent tracheostomy at the time of writing. However, no patients convincingly demonstrated complete restoration of voice, swallowing, and oronasal breathing, although three patients had significant performance in all three functions. Hence, patients were left with the options facing all patients with bilateral vocal cord paralysis: an open position improving breathing but weakening voice and exposure to aspiration, a closed position with improved voice and reduced aspiration but impaired airway, or some intermediate compromise. In our series, procedures to open the airway further were sometimes performed prioritizing breathing (and thus tracheostomy-free existence) over better voice and swallowing. Again, without formal measurements of these parameters, with their psychosocial outcomes, assessing which is the preferred default vocal cord position after transplantation is difficult. The addition of selective laryngeal reinnervation,17-19 laryngeal pacemakers, and/or robotic implants could provide step changes for laryngeal transplantation as a more generally applicable therapy and could deliver consistently high quality-of-life outcomes for recipients.20

The place of laryngeal transplantation in head and neck oncology has been questioned due to the need for immunosuppression and therefore possible tumor recurrence. However, here we show the feasibility of laryngeal transplant in treated cancer patients experiencing laryngeal carcinoma such as squamous cell carcinoma of the larynx, Hodgkin's lymphoma, and severe radiotherapy fibrosis, respectively. There was no sign of recurrence in these patients at the time of writing, and the patients have reported to be 10, 6, and 24 years cancer-free, respectively. This suggests a place for this procedure in improving functional outcomes of reconstruction in patients with advanced head and neck cancer. The ultimate goal of laryngeal transplantation is to provide airway patency, normal voice, and swallowing by decreasing the inherent risk related to allograft transplantation such as risk opportunistic infection, secondary malignancy, GVHD, rejection, lifelong immunosuppression risk, and loss of function.

CONCLUSION

In summary, laryngeal transplantation for carefully selected patients is demanding of both recipients and surgical teams and raises important ethical and technical questions. However, it is technically feasible with good graft survival rates and complications that are mostly manageable. Recovery of airway, swallowing, and voice to acceptable levels are achieved by 1 year in some cases, with further improvements possible during year 2 posttransplant. The majority of patients achieved at least satisfactory voice by 8 months, and some gained good or excellent recovery. Nonetheless, this is a very major procedure with significant mortality and morbidity and should still be regarded as experimental or “compassionate use” only for the time being. This may change, however, if new means for restoration of motor function (such as improved reinnervation or pacing) and lower morbidity immunomodulation are forthcoming. Future work also should include the development of common validated outcome measurements, including psychosocial measures, surgical and rehabilitation protocols, and rejection criteria; the consideration of service needs, including economics and training; and a standardized approach to informed consent. Studies of the pathogenesis of chronic rejection, and thus strategies for early detection and management, are also needed. Our 11 reported cases provide new and important baseline information to inform future research and clinical efforts in the arena of laryngeal transplantation.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank our respective health care institutions for their support in hosting these procedures. We thank our theater, intensive care ward, and outpatient staff for their skill and dedication without which these patients would not have had these opportunities for a new, augmented life. We thank the transplant networks of Ohio, California, Colombia, and Poland for helping secure rare and precious donor organs. We especially thank the families of those taken too soon from this world, who at a time of consummate grief, generously provided permission for the donation of organs to these programs and thereby to their grateful recipients. Carlos Andres Valdez for his outstanding medical illustrations that exemplify the vascular anastomosis and reinnervations.