Suture Stenting After Sialendoscopy: A Novel Technique That Reduces Risk of Recurrent Parotitis

Editor's Note: This Manuscript was accepted for publication on June 06, 2023.

a.f. and j.c. contributed equally to this work.

The authors have no funding, financial relationships, or conflicts of interest to disclose.

Abstract

Objective

Chronic sialadenitis is associated with decreased quality of life and recurrent infections. While sialendoscopy with stenting is effective in relieving symptoms of sialadenitis, currently available stents are rigid and poorly tolerated by patients, leading to early removal and potential for adverse scarring. This study examines whether sutures can be used as a stenting material to improve patient comfort and reduce recurrence risk.

Methods

This is a retrospective cohort study of a consecutive series of adult patients with chronic sialadenitis undergoing sialendoscopy with or without suture stenting. Data were collected between 2014 and 2018 with a 3-year follow-up period ending in 2021. The primary outcome measure was recurrence of sialadenitis within 3 years of surgery. Secondary outcomes were stent dislodgement and patient-reported discomfort.

Results

We included 63 patients with parotid sialadenitis of whom 28 underwent suture stenting and 35 did not receive stenting after sialendoscopy. Stents were well tolerated, with a mean duration of 34.5 days, and only 2 of 28 stents (7.1%) accidentally dislodged within the first week. Suture stenting significantly reduced symptom recurrence after sialendoscopy (OR = 0.09, 95% CI 0.02–0.45, p = 0.003; 3-year sialadenitis recurrence rate: 7.1% vs. 45.7%, p = 0.005). Cox multivariate regression for clinicodemographic variables showed an HR of 0.04 (95% CI 0.01–0.19, p < 0.001) for the risk of symptom recurrence.

Conclusions and relevance

Suture stenting after sialendoscopy is low cost, available across all institutions, well-tolerated by patients, and highly efficacious in reducing risk of recurrent sialadenitis after sialendoscopy.

Level of Evidence

3 Laryngoscope, 134:614–621, 2024

INTRODUCTION

Chronic sialadenitis is a condition characterized by inflammation of the salivary ducts that can be caused by sialolithiasis, radioactive iodine treatment, and iatrogenic or idiopathic scarring. While its incidence is rare, with estimates around 1 in 10,000–30,000,1 it can have a debilitating effect on patients. Recurrent infections and symptoms lead to decreased quality of life symptom scores, increased clinic visits and hospitalizations, and increased health care costs.1-3

Sialadenitis management is comprised of both medical and surgical management. Medical management includes conservative measures that encourage salivary egress to limit stagnant flow that can lead to infections as well as antibiotic therapy for acute salivary gland infections. Surgical options were previously limited to open sialolithotomy and submandibular or parotid gland excision, but a minimally invasive approach, sialendoscopy, emerged in the 1990s.4, 5 Sialendoscopy is performed by placing a semi-rigid endoscope through the parotid or submandibular duct papilla, allowing visualization and placement of flexible instrumentation in the duct system. It is highly effective at improving symptoms of chronic sialadenitis, with a recent systematic review of 1285 patients undergoing sialendoscopy showing a mean success rate of 88.7% among 109 articles.6 Additionally, sialendoscopy is associated with improved quality of life scores in patients and is cost-effective relative to salivary gland excision.3, 7

While sialendoscopy is generally safe and effective, re-stenosis and scarring are known post-surgical complications that can affect long term success. To mitigate this risk, stents have been used to promote luminal patency during healing. However, current salivary stents are rigid or semi-rigid and associated with high (33%–66%) rates of irritation, variable rates of obstruction, and potential for migration or extrusion depending on the material used.8 Commercially available stents are commonly used, but they tend to be made of polyurethane and can be too rigid for comfortable placement in patients. Therefore, stent material varies among institutions and can consist of hypospadias tubes, pediatric feeding tubes, or silicone. A recent study also reported the use of a bioresorbable stent made of poly-L-lactide in animal models, but it has not been used in patients.9 Due to these issues, improvements in stenting material or techniques would be of benefit to patients.

This article describes a novel salivary duct stent using widely available suture material that can be applied to the parotid and submandibular ducts. The stenting system fulfills critical needs after sialendoscopy and is low cost, comfortable for patients, and efficacious for long-term symptom relief. Additionally, the article directly compares stented and non-stented groups, which has not previously been reported.

METHODS

Patients

This study was approved by the Institutional Review Board at Stanford University. Adults who underwent initial therapeutic sialendoscopy at Stanford Hospital between January 2014 and January 2018 were identified using the unlisted Current Procedural Terminology (CPT) code 42699 for sialendoscopy and the International Classification of Diseases 10th Revision (ICD-10) codes K11.20–K11.23 for sialadenitis and K11.5 for sialolithiasis. Surgical operative reports, pathology reports, imaging reports, and outpatient clinical notes were extracted from the electronic medical record (EMR) until the study's end date in January 2021. After review of all surgical operative reports, the earliest sialendoscopy in each salivary gland was identified as the index sialendoscopy. Salivary glands previously treated at other institutions with sialendoscopy were excluded.

Demographic and clinical characteristics, including age, sex, history of radioiodine treatment, radiation therapy, Sjogren's syndrome, diabetes, diuretic medication use, and bruxism, were retrieved from outpatient clinical notes. Stent placement and operative details, including concurrent sialodochoplasty, were recorded based on operative reports. Salivary duct lithiasis (L), stenosis (S), and dilatation (D) were classified using the LSD classification system by Marchal et al.10 and recorded based on sialendoscopy findings documented in operative reports.

All outpatient clinical notes filed after sialendoscopy were reviewed. Complete resolution, partial resolution, and/or recurrence of sialadenitis symptom frequency at the time of each follow-up visit was recorded based on patient-reported symptoms. These symptoms included pain, swelling, or purulent drainage at the affected salivary gland. Absence of these symptoms was recorded as complete resolution of sialadenitis symptoms. Dates of revision salivary gland surgeries were recorded.

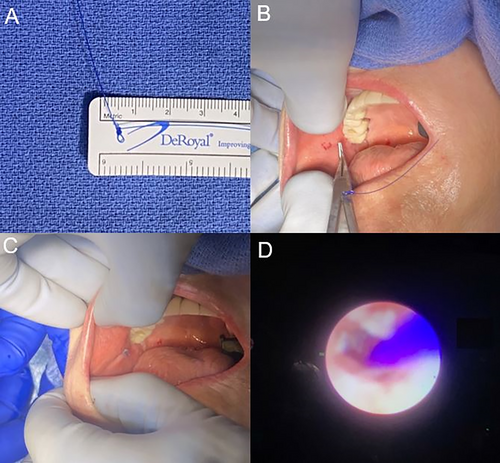

Procedure

Sialendoscopy was performed using Karl Storz semi-flexible all-in-one endoscopes under continuous irrigation and direct visualization. If the parotid duct papilla could not be cannulated, dilation over a guidewire was performed for access. In rare cases of complete stenosis at the papilla, incision was performed for access. For cases of stenosis or scar, the ductal system was sequentially dilated using sialendoscopy dilators and re-evaluated using sialendoscopy to ensure patency. In cases of sialolithiasis, all attempts were made to retrieve the stone using baskets through the papilla, but in some cases a direct incision was necessary due to large stone size or scarring that prevented delivery of the stone. The primary surgeon (DS) determined whether stenting was necessary. The primary criteria for stent placement were long-segment (>3 cm) stenosis and circumferential scarring indicated by hyperemia or changes to the ductal mucosa. In patients undergoing stenting, a 2–0 Ethicon prolene suture (Johnson & Johnson, Raritan, NJ) or 3–0 Covidien V-loc suture (Medtronic, Minneapolis, MN) was placed through the papilla to act as a stent. The depth of the stenotic segment was measured using the endoscope from the parotid papilla. Suture material was placed through the papilla without using the endoscope to a depth beyond the stenotic segment. Direct visualization using the endoscope was then used to confirm placement. The prolene stent was then secured to the mucosa by creating a small proximal knot and threading a 3–0 nylon suture through the knot, which was tied to the buccal or floor of mouth mucosa (Fig. 1).

The goal of suture stenting was to develop a durable stent that could be maintained to prevent adverse scarring. Absorbable Covidien V-loc suture was cut at the papilla and allowed to resorb on its own. Prolene sutures were left for up to 14 weeks, depending on the extent of scarring and symptom relief the stent provided to the patient. Stents were removed on follow-up visits after at least 2 weeks and left in longer if patients were amenable. Once the surgeon (DS) determined the ductal system had sufficient time for healing or there was accidental decannulation, the stent was removed in the office.

Outcomes

The primary endpoint of our study compared symptom recurrence between stented and non-stented salivary glands after sialendoscopy. Recurrence time was measured from the date of sialendoscopy to the date of symptom recurrence. Cases were censored at the last follow-up visit, death, or 3 years after surgery, whichever occurred earlier. Secondary outcomes of suture dislodgement or early suture removal due to pain or discomfort were also recorded.

Statistical Analysis

All statistical analyses were performed using Stata version 14.2 (StataCorp, College Station, TX) and R version 3.6.2 (R Foundation for Statistical Computing, Vienna, Austria). Chi-squared and student's t-tests were performed to compare baseline variables between the stented and non-stented groups. Univariate analysis of symptom recurrence data was performed using Kaplan–Meier curves, and unadjusted p-values were calculated using log-rank tests. The proportional hazard assumption was quantitatively tested using Schoenfeld residuals, which were insignificant in all Cox regression models (p > 0.05). Multivariate-adjusted Cox regression analysis was performed in all salivary glands and in the parotid gland cohort to assess the effect of stent placement on symptom recurrence after sialendoscopy.

RESULTS

Demographics

A total of 63 patients were included in this study with 28 undergoing stenting (Stent) and 35 no stenting (NonStent) at time of salivary duct dilation (Table I). The median age was 50.2 ± 15.3 (mean ± standard deviation) and 36.5% of patients were male without differences between groups. There was also no significant difference in past medical history, operative technique, or operative time. There were no significant differences between the Stent and NonStent diagnostic indications except for a higher rate of Sjogren's syndrome in the NonStent group (22.9% vs. 0%, p = 0.02).

| Variables | Parotid Glands | Parotid Stented Glands | Parotid Non-stented Glands | p-value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| (n = 63) | (n = 28) | (n = 35) | ||

| Age, years, mean (SD) | 50.21 (15.26) | 46.62 (15.55) | 53.08 (14.61) | 0.1 |

| Male, n (%) | 23 (36.5) | 9 (32.1) | 14 (40.0) | 0.704 |

| Primary diagnostic indication, n (%) | ||||

| Chronic sialadenitis | 34 (54.0) | 13 (46.4) | 21 (60.0) | 0.692 |

| Lithiasis | 6 (9.5) | 3 (10.7) | 3 (8.6) | |

| Radioiodine (RAI)-induced stenosis | 20 (31.7) | 10 (35.7) | 10 (28.6) | |

| Radiotherapy-induced stenosis | 3 (4.8) | 2 (7.1) | 1 (2.9) | |

| Pertinent past medical history, n (%) | ||||

| Sjogren's syndrome, n (%) | 8 (12.7) | 0 (0.0) | 8 (22.9) | 0.02 |

| Diabetes mellitus, n (%) | 3 (4.8) | 2 (7.1) | 1 (2.9) | 0.843 |

| Diuretic medication use, n (%) | 4 (6.3) | 1 (3.6) | 3 (8.6) | 0.773 |

| History of bruxism, n (%) | 9 (14.3) | 5 (17.9) | 4 (11.4) | 0.717 |

| Clinical follow-up time, m, mean (SD) | 13.61 (12.28) | 12.07 (9.93) | 14.84 (13.89) | 0.378 |

| Operative technique, n (%) | ||||

| Sialendoscopy alone | 54 (85.7) | 24 (85.7) | 30 (85.7) | 0.894 |

| Combined with ductoplasty | 6 (9.5) | 3 (10.7) | 3 (8.6) | |

| Combined with partial or complete gland resection | 3 (4.8) | 1 (3.6) | 2 (5.7) | |

| Lithiasis (L) classification, n (%) | ||||

| L0, no stone | 56 (88.9) | 25 (89.3) | 31 (88.6) | 0.295 |

| L1, floating stone | 2 (3.2) | 1 (3.6) | 1 (2.9) | |

| L2a, fixed stone, completely visible, <8 mm | 2 (3.2) | 2 (7.1) | 0 (0.0) | |

| L2b, fixed stone, completely visible, ≥8 mm | 1 (1.6) | 0 (0.0) | 1 (2.9) | |

| L3a, fixed stone, partially visible, palpable | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | |

| L3b, fixed stone, partially visible, non-palpable | 2 (3.2) | 0 (0.0) | 2 (5.7) | |

| Stenosis (S) classification, n (%) | ||||

| S0, no stenosis | 3 (4.8) | 1 (3.6) | 2 (5.7) | 0.557 |

| S1, web-like stenosis | 1 (1.6) | 0 (0.0) | 1 (2.9) | |

| S2, single short <10 mm stenosis | 17 (27.0) | 10 (35.7) | 7 (20.0) | |

| S3, multiple or long 10–29 mm stenoses | 27 (42.9) | 10 (35.7) | 17 (48.6) | |

| S4, diffuse ≥30 mm stenosis | 15 (23.8) | 7 (25.0) | 8 (22.9) | |

| Dilatation (D) classification, n (%) | ||||

| D0, no dilatation | 57 (90.5) | 26 (92.9) | 31 (88.6) | 0.295 |

| D1, single dilatation | 2 (3.2) | 1 (3.6) | 1 (2.9) | |

| D2, multiple dilatations | 3 (4.8) | 0 (0.0) | 3 (8.6) | |

| D3, diffuse dilatation | 1 (1.6) | 1 (3.6) | 0 (0.0) | |

- p-values were calculated between the stented (n = 28) and non-stented groups (n = 35).

Stent Duration

Clinicodemographic variables of patients undergoing salivary gland suture stenting are presented in Table II. Stenting was well-tolerated among patients with an average stent duration of 31.5 days (range 6–100 days). There were no cases requiring removal of the stent due to pain, discomfort, infection, or symptom recurrence. Out of 27 patients receiving prolene sutures, 10 (37.0%) had accidental dislodgement at an average of 13.4 ± 11.5 days after surgery (range 6–45 days). There was no difference in symptom recurrence among patients that had accidental dislodgement to those who had in-office removal.

| Case | Age and sex | Gland | Primary diagnostic indication | Pertinent past medical history | Type of suture stent | Days with stent in place | Stent removal method | Symptom recurrence | Revision surgery |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 37F | Parotid | RAI-induced stenosis | None | Prolene, size 1 | 65 | In-office | None | None |

| 2 | 37F | Parotid | RAI-induced stenosis | None | Prolene, size 1 | 65 | In-office | None | None |

| 3 | 62F | Parotid | Lithiasis | Non-insulin dependent diabetes | Prolene, size 1 | 37 | In-office | None | None |

| 4 | 38F | Parotid | Chronic sialadenitis | None | Prolene, size 1 | 44 | In-office | None | None |

| 5 | 38F | Parotid | Chronic sialadenitis | None | Prolene, size 1 | 44 | In-office | None | None |

| 6 | 60F | Parotid | Radiation-induced stenosis | None | Prolene, size 1 | 45 | Accidental dislodgement | None | None |

| 7 | 60F | Parotid | Radiation-induced stenosis | None | Prolene, size 1 | 12 | Accidental dislodgement | None | None |

| 8 | 85M | Parotid | Chronic sialadenitis | None | Prolene, size 1 | 9 | In-office | None | None |

| 9 | 34F | Parotid | RAI-induced stenosis | None | Prolene, size 0 | 44 | In-office | None | None |

| 10 | 34F | Parotid | RAI-induced stenosis | None | Prolene, size 0 | 44 | In-office | None | None |

| 11 | 33F | Parotid | Chronic sialadenitis | Bruxism | Prolene, size 0 | 16 | In-office | Symptoms recurred 1 month after index sialendoscopy | None |

| 12 | 59F | Parotid | Chronic sialadenitis | None | Prolene, size 2–0 | 100 | In-office | None | None |

| 13 | 59F | Parotid | Chronic sialadenitis | None | Prolene, size 2–0 | 100 | In-office | None | None |

| 14 | 30F | Parotid | RAI-induced stenosis | None | Prolene, size 2–0 | 44 | In-office | None | None |

| 15 | 30F | Parotid | RAI-induced stenosis | None | Prolene, size 2–0 | 9 | Accidental dislodgement | None | None |

| 16 | 32M | Parotid | RAI-induced stenosis | None | Prolene, size 2–0 | 10 | Accidental dislodgement | None | None |

| 17 | 66M | Parotid | Chronic sialadenitis | None | Prolene, size 2–0 | 30 | In-office | Symptoms recurred 13 months after index sialendoscopy | None |

| 18 | 61F | Parotid | Chronic sialadenitis | None | Prolene, size 2–0 | 16 | In-office | None | None |

| 19 | 48F | Parotid | Chronic sialadenitis | Bruxism | Prolene, size 3–0 | 12 | Accidental dislodgement | None | None |

| 20 | 62M | Parotid | Chronic sialadenitis | None | Prolene, size 3–0 | 60 | In-office | None | None |

| 21 | 33M | Parotid | Chronic sialadenitis | Bruxism | Prolene, size 3–0 | 16 | Accidental dislodgement | Symptoms recurred 3 months after index sialendoscopy | Revision stent placement performed 5 months after index sialendoscopy |

| 22 | 35M | Parotid | RAI-induced stenosis | None | Prolene, size 3–0 | 8 | Accidental dislodgement | None | None |

| 23 | 35M | Parotid | RAI-induced stenosis | None | Prolene, size 3–0 | 6 | Accidental dislodgement | None | None |

| 24 | 31M | Parotid | Chronic sialadenitis | Bruxism | Prolene, size 3–0 | 10 | Accidental dislodgement | None | None |

| 25 | 63F | Parotid | Lithiasis | None | Prolene, size 3–0 | 6 | Accidental dislodgement | None | None |

| 26 | 44F | Parotid | RAI-induced stenosis | None | Prolene, size NOS | 16 | In-office | None | None |

| 27 | 69M | Parotid | Chronic sialadenitis | Diuretic use | Prolene, size NOS | 58 | In-office | None | None |

| 28 | 31F | Parotid | Chronic sialadenitis | Bruxism | Covidien, size 3–0 | (44) | - | None | None |

- Last post-operative follow-up day is reported for the absorbable Covidien V-Loc stent.

Outcomes

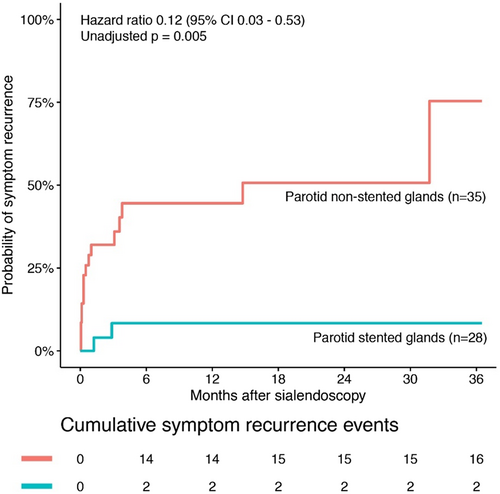

Stent and NonStent groups were compared for symptom recurrence after sialendoscopy. Suture stenting significantly reduced the rate of recurrent sialadenitis after surgery (OR = 0.09, 95% CI 0.02–0.45, p = 0.003) (Fig. 2). The 3-year success rate in the Stent group was 92.9% compared with 54.3% in the NonStent group (log-rank p = 0.005) (Fig. 2).

We compared the 2 patients with recurrent symptoms within 1 year of stent placement to the 16 patients with recurrent symptoms in the NonStent group (Table III). There were no significant differences between the two groups on clinicodemographic variables. These patients similarly matched the overall group of patients in that the majority of them had long segment (>10 mm) stenosis of the duct.

| Variables | All Glands with Recurrence (N = 18) | All Stented Glands with Recurrence (n = 2) | All Non-Stented Glands with Recurrence (n = 16) | p |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age, years, mean (SD) | 47.57 (15.08) | 32.81 (0.35) | 49.42 (15.00) | 0.147 |

| Male, n (%) | 8 (44.4) | 1 (50.0) | 7 (43.8) | 1.000 |

| Primary diagnostic indication, n (%) | ||||

| Chronic sialadenitis | 11 (61.1) | 2 (100.0) | 9 (56.2) | 0.489 |

| Lithiasis | 2 (11.1) | 0 (0.0) | 2 (12.5) | |

| Radioiodine (RAI)-induced stenosis | 5 (27.8) | 0 (0.0) | 5 (31.2) | |

| Radiotherapy-induced stenosis | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | |

| Pertinent past medical history, n (%) | ||||

| Sjogren's syndrome, n (%) | 1 (5.6) | 0 (0.0) | 1 (6.2) | 1.000 |

| Diabetes mellitus, n (%) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 1.000 |

| Diuretic medication use, n (%) | 1 (5.6) | 0 (0.0) | 1 (6.2) | 1.000 |

| History of bruxism, n (%) | 6 (33.3) | 2 (100.0) | 4 (25.0) | 0.185 |

| Clinical follow-up time, m, mean (SD) | 14.33 (9.72) | 2.05 (1.15) | 15.86 (9.19) | 0.055 |

| Operative technique, n (%) | ||||

| Sialendoscopy alone | 16 (88.9) | 2 (100.0) | 14 (87.5) | 0.869 |

| Combined with ductoplasty | 1 (5.6) | 0 (0.0) | 1 (6.2) | |

| Combined with partial or complete gland resection | 1 (5.6) | 0 (0.0) | 1 (6.2) | |

| Lithiasis (L) classification, n (%) | ||||

| L0, no stone | 16 (88.9) | 2 (100.0) | 14 (87.5) | 0.869 |

| L1, floating stone | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | |

| L2a, fixed stone, completely visible, <8 mm | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | |

| L2b, fixed stone, completely visible, ≥8 mm | 1 (5.6) | 0 (0.0) | 1 (6.2) | |

| L3a, fixed stone, partially visible, palpable | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | |

| L3b, fixed stone, partially visible, non-palpable | 1 (5.6) | 0 (0.0) | 1 (6.2) | |

| Stenosis (S) classification, n (%) | ||||

| S0, no stenosis | 1 (5.6) | 0 (0.0) | 1 (6.2) | 0.690 |

| S1, web-like stenosis | 1 (5.6) | 0 (0.0) | 1 (6.2) | |

| S2, single short <10 mm stenosis | 4 (22.2) | 0 (0.0) | 4 (25.0) | |

| S3, multiple or long 10–29 mm stenoses | 9 (50.0) | 1 (50.0) | 8 (50.0) | |

| S4, diffuse ≥30 mm stenosis | 3 (16.7) | 1 (50.0) | 2 (12.5) | |

| Dilatation (D) classification, n (%) | ||||

| D0, no dilatation | 16 (88.9) | 2 (100.0) | 14 (87.5) | 0.869 |

| D1, single dilatation | 1 (5.6) | 0 (0.0) | 1 (6.2) | |

| D2, multiple dilatations | 1 (5.6) | 0 (0.0) | 1 (6.2) | |

| D3, diffuse dilatation | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | |

A multivariate Cox regression was performed to control for clinicodemographic variables as well as lithiasis, stenosis, and dilation classification. After adjustment for covariates, there was a significant effect of stenting on reducing post-operative recurrence (p < 0.001) (Table IV).

| Multivariate hazard ratio for symptom recurrence in stented versus non-stented glands (95% CI) | p | |

|---|---|---|

| Parotid glands (n = 63) | 0.04 (0.01–0.19) | <0.001 |

- Multivariate analysis adjusted for baseline variables (age, sex, gland type, Sjogren's syndrome, and primary diagnostic indication for sialendoscopy), and lithiasis (L), stenosis (S), and dilatation (D) classification.

DISCUSSION

We report a novel suture based stenting system for sialendoscopy procedures that is low cost, available across all institutions, well-tolerated by patients, and highly efficacious at reducing risk of recurrent sialadenitis and sialolithiasis after sialendoscopy and dilation. The stent can be applied to both parotid and submandibular glands and has very low rates of accidental dislodgement, with only 2 of 28 patients dislodging the stent in the first week. Additionally, we report significantly better outcomes after stenting in clinically similar patients with sialadenitis undergoing sialendoscopy, offering evidence in favor of stenting that is not currently available in the literature. This is especially surprising since patients that underwent stenting were likely to have higher risk of scarring due to presence of circumferential and/or long segment stenosis compared with those that were not stented. Given these results, we advocate for wider adoption of this suture stenting system among otolaryngologists performing sialendoscopy.

While suture stenting has not been reported in otolaryngology, new suture stents are becoming more widely adopted in urology and have interesting similarities to stents used in sialendoscopy. These stents are specifically adapted for ureteroscopy with stone removal, where rigid stents are also associated with patient discomfort as well as biofilms.11 These stents use a pigtail catheter in the collecting system of the kidney connected to a suture through the ureter into the bladder to maintain a patent lumen (Rocamed, Southborough, MA). Since these urologic suture stents are commercial products, blinded, randomized controlled trials have been performed to demonstrate clinical efficacy of these devices. Multiple trials have now shown that ureteral suture stents are associated with significantly better patient-reported outcomes in pain and urinary symptoms compared with conventional stents at both 2 days and 2 weeks postoperatively.12, 13 These results in the urology literature coupled with the results of our study indicate suture stents are useful in maintaining patency of biological lumens without causing significant discomfort to patients. While our results use widely available suture material as a simple stent that does not require regulatory approval, direct comparisons with existing sialendoscopy stents may be useful to demonstrate efficacy in reducing stent-related discomfort.

During this initial period in our study, suture sialendoscopy stents were used in patients with recurrent parotid sialadenitis, which has important distinctions from submandibular sialadenitis. Notably, the parotid gland is less likely to be impacted by sialolithiasis, with only 2 of 28 (7.1%) patients with parotid sialadenitis having stones in this study. Therefore, the primary mechanisms of parotid duct obstruction tend to be inflammatory, including recurrent infections, autoimmune, RAI, traumatic, or idiopathic causes.14 These inflammatory causes are likely to increase risk of recurrent symptoms after sialendoscopy compared with sialolithiasis, which has extremely low rates of recurrence after stone removal from the parotid gland.15 In a 2019 study by Lele et al. of chronic parotid sialadenitis without sialolithiasis, 12 of 22 patients achieved a complete response following sialendoscopy with dilation and corticosteroid injection but without stent placement.16 While local effects of corticosteroids are likely to temporarily prevent stricture formation, adding stents may aid in long-term patency of the ductal lumen as it heals. Stenting can be added to corticosteroids for inflammatory chronic sialadenitis and will be interesting to study as evidence builds for efficacy of corticosteroids in sialadenitis.

RAI was an important cause of sialadenitis in this cohort, with 31.7% of parotid sialadenitis patients undergoing prior RAI treatment. Salivary glands have increased levels of iodine, which causes both acute and chronic effects following RAI. Five years after a single RAI ablation, 41.7% of patients had evidence of salivary gland dysfunction in a study of 213 patients undergoing thyroid cancer treatment.17 Parotid glands tend to be more susceptible to RAI,18 which is consistent with the data in this study. Sialendoscopy has success rates of about 75%–90% for RAI-induced sialadenitis.19-21 Interestingly, Douglas et al.20 reported a trend (61.5% vs. 87.0%) toward better outcomes when a stent was used, though the specific type of stent was not reported in their study. Of the 10 patients with RAI who had stent placement in this study, 100% had symptom resolution, indicating this is a potentially viable treatment strategy for this group.

The primary suture material used in this study was Prolene, which is a non-absorbable, synthetic monofilament suture material commonly used in closure of surgical wounds and vascular anastomosis. It is most commonly used due to the low rates of inflammatory changes from the suture material, which can be left in place indefinitely. Due to these properties, Prolene has applications as a stenting material in ophthalmology, where previous groups have reported using it for dacryocystorhinostomy and lacrimal canaliculi repair.22, 23 The primary disadvantage with Prolene is that it is a permanent suture that requires eventual removal from the salivary duct, which needs to be performed in a clinic and can cause discomfort. One patient in this study received Covidien V-Loc suture, which is a barbed, absorbable suture made of glycolide, dioxanone, and trimethylene carbonate that has an absorption time of 90–110 days in soft tissue. The barbs prevented migration out of the salivary duct and did not require any sutures for fixation; additionally, they were not associated with patient discomfort in this study. This suture type has advantages over Prolene but needs additional patient data to determine if it is as efficacious. Comparison to existing sialendoscopy stents will also be important. Commercially available stents for sialendoscopy include the Schaitkin salivary duct cannula (Hood Labs, Pembroke, MA, USA) and the Walvekar salivary duct stent (Hood Labs). These stents are made of silicone and Pebax, respectively, and are also sutured to the surrounding mucosa to prevent migration. Since these stents have a much wider diameter (0.6–1.5 mm) than suture stents, they may be associated with increased pressure on the tissues and discomfort. Additionally, risk of migration into the duct and a retained foreign body is much more of a concern compared with suture. Randomized controlled trials are likely needed to determine the optimal stenting material for reducing patient discomfort and preventing recurrence of sialadenitis.

The optimal duration of suture stenting also needs to be established, and there are no studies in the literature that address this issue after sialendoscopy. In this study, the goal was to leave the suture stents in as long as possible to ensure healing over an open lumen and prevent adverse scarring. Most stents were removed after 30 days in this study at a timepoint coinciding with a follow-up visit. Since these patients are prone to scarring, the thought was that a longer duration of stenting was more optimal. However, there was selection bias in deciding when stents were removed, with some patients maintaining stents for up to 100 days. Despite this large range, this study does provide important information regarding stent duration and suggests longer stenting (>2 weeks) may be effective. Additional studies are needed to determine the optimal stent duration.

This study provides important evidence for stenting following sialendoscopy but has important limitations. The first is selection bias in determining which patients underwent stenting and which did not. While the clinicodemographic variables were similar between groups, patients that were stented presumably had clinical concern for recurrence at time of sialendoscopy. This suggests they should have had worse outcomes than patients who were not stented. Though their better outcomes argue that stenting was effective, it is possible other factors contributed to recurrence in the non-stented patients that could not be ascertained during sialendoscopy. Additionally, the retrospective nature of the data and cases performed at a single institution are also important limitations. This study also focuses on parotid sialendoscopy, which tends to be more inflammatory in nature. Understanding how stenting affects submandibular sialadenitis will be important to study in the future. The high rate of accidental decannulation (35.7%) may also be a potential limitation of the technique. The vast majority of these occurred after 1 week, possibly from sutures migrating out of the tissue due to long duration of implant. This timepoint is still likely longer than most rigid or flexible commercial stents are left in place, though practice patterns are likely to differ significantly between surgeons. Improving the way Prolene suture is anchored or using an absorbable suture stent may be ways to overcome this issue.

CONCLUSION

In conclusion, we present evidence for significant improvement in post-sialendoscopy symptoms of sialadenitis using salivary duct stents during a 3-year follow-up period. This result was achieved using widely available, inexpensive suture stents that were very well tolerated by patients. These results are expected to have important implications for management of patients after sialendoscopy.