Domains of self-uncertainty and their relationship to group identification

Abstract

Uncertainty-identity theory research shows that self-uncertainty, directly or indirectly manipulated or measured, motivates group identification. Untested is an assumption that it is collective identity-focused uncertainty that most directly motivates identification. Two studies tested this assumption. Study 1 (N = 140) measured self-uncertainty relating to different aspects of self, with the expectation they would cluster into three distinct domains—individual, relational, collective self-uncertainty. This expectation was supported. Study 2 (N = 382) manipulated uncertainty (low, high) and domain of self (individual, relational, collective) in a 2 × 3 design and measured identification. As predicted uncertainty strengthened identification (H1) and this was moderated by domain (H2)—it was only significant on collective self. Implications for self-uncertainty fluidity and uncertainty reduction through group identification are discussed.

1 INTRODUCTION

Social psychologists have long considered uncertainty to play a significant role in motivating human behavior (e.g., Fromm, 1947), and there are many social psychological analyses of the causes and consequences of various manifestations of uncertainty (e.g., Heine, Proulx, & Vohs, 2006; Kahneman, Slovic, & Tversky, 1982; Kruglanski & Webster, 1996), not least social comparison theory (e.g., Festinger, 1954; Suls & Wheeler, 2000). In recent years, there has also been an emphasis specifically on uncertainty related to or focused on the self (e.g., Arkin, Oleson, & Carroll, 2010; Hogg, 2007; McGregor, Prentice, & Nash, 2009; Van den Bos, 2009). The focus of the present research is on one specific conceptualization of the relationship between self-uncertainty and human behavior—uncertainty-identity theory (Hogg, 2000, 2007, 2012).

Uncertainty-identity theory is a motivational account of group identification and group and intergroup phenomena. The key premise is that self-conceptual uncertainty motivates group identification. Uncertainty, particularly uncertainty about oneself or about things that directly matter to or reflect on who we are, can be aversive. People strive to reduce feelings of uncertainty about themselves, their social world and their place within it—they like to know who they are and how to behave, and who others are and how they might behave. Being properly located in this way renders the world and one's place within it relatively predictable and allows one to plan effective action, avoid harm, know who to trust, and so forth.

Group identification is very effective at reducing or protecting against self-related uncertainty. This is because identification is associated with social categorization of self and others—a process that depersonalizes behavior and perception of self and other's to conform to group prototypes that describe and prescribe how people (including oneself) will and ought to behave and interact with one another (Abrams & Hogg, 2010; Turner, Hogg, Oakes, Reicher, & Wetherell, 1987). Social categorization of self and others generates a sense of ingroup identification and belonging, and regulates perception, inference, feelings, behavior, and interaction to conform to prototype-based knowledge one has about one's own group and relevant outgroups. Furthermore, because group prototypes are shared (“we” agree “we” are like this, “they” are like that) one's worldview and self-concept are consensually validated. Social categorization makes one's own and others' behavior predictable, and allows one to avoid harm, plan action, and know how one should feel and behave.

Some types of groups and some features of groups are more effective than others in reducing uncertainty through identification. Highly entitative groups (Campbell, 1958; Hamilton & Sherman, 1996), which are distinctive, homogeneous, and clearly structured, provide common goals and a clearly defined identity and are therefore particularly effective—entitativity moderates the relationship between self-uncertainty and identification (e.g., Hogg, Sherman, Dierselhuis, Maitner, & Moffitt, 2007). Groups that have an indistinct and fuzzy identity are not very effective at reducing uncertainty (e.g., Wagoner & Hogg, 2016). People also need to feel they are a good fit to the group's identity and will therefore be accepted and have their identity validated by the group (e.g., Goldman & Hogg, 2016; Hohman, Gaffney, & Hogg, 2017). Groups that people feel they do not fit well, and that they are unlikely to be fully accepted and validated by, are not very effective at reducing self-conceptual uncertainty.

Research on uncertainty-identity theory has provided robust support for the basic predictions: uncertainty, however caused but most strongly if it is self/identity or self/identity-related uncertainty, triggers identification with a self-inclusive category; people identify more strongly with groups when they are feeling uncertain; uncertainty-based identification can reduce uncertainty; the uncertainty–identification relationship is most pronounced when the dimension of uncertainty is subjectively important and when the social group is relevant to the dimension of uncertainty; and under uncertainty people identify more strongly with high than low entitativity groups and distance themselves from low entitativity groups (see empirical reviews by Hogg, 2007, 2012). The motivational effect of uncertainty on group identification has also been shown to be independent of and unmediated by self-enhancement and self-esteem concerns (Hogg & Hohman, 2017; Reid & Hogg, 2005).

Research has also provided support for a key development of uncertainty-identity theory—specifically its analysis of group- and identity-based extremism in society (Hogg, 2014), which is part of a recent narrative linking various forms of uncertainty reduction motivation to manifestations of societal extremism (see Hogg, Kruglanski, & Van den Bos, 2013). Uncertainty strengthens preference for and identification with more extremist groups (e.g., Hogg, Adelman, & Blagg, 2010) and ideologies (e.g., Hogg et al., 2010), strengthens preference and support for more autocratic and populist leadership (e.g., Hogg, Van Lange, Kruglanski, & Higgins, 2012; Rast & Hogg, 2017; Rast, Hogg, & Giessner, 2013), and encourages group members to go to intergroup extremes for their group (e.g., Goldman & Hogg, 2016).

1.1 Domains of self-uncertainty

One very notable omission from uncertainty-identity theory research, an omission that compromises the theory's conceptual precision, is an exploration of what aspect of self a person may feel uncertain about, and how different dimensions of self-uncertainty may relate to one another and affect group identification. Very early studies of the relationship between uncertainty and group identification manipulated self-related uncertainty in indirect ways—for example, by making student participants feel more or less uncertain about an experimental task they had to perform or about their interpretation of stimuli (e.g., Grieve & Hogg, 1999; Mullin & Hogg, 1998), or about important attitudes they held (e.g., Mullin & Hogg, 1999). These paradigms were predicated on the belief that uncertainties, however induced, that reflected on self would create the sort of self-uncertainty that uncertainty-identity theory predicted would motivate group identification. It was assumed that the experimental context of these tasks (psychology students performing a task in a psychology experiment in the psychology department) would cause task-related uncertainty to induce self-related uncertainty.

Later, and all subsequent, studies focused directly on manipulating or measuring self-uncertainty directly. Self-uncertainty has mainly been manipulated by a cognitive prime in which participants are asked to take some time thinking about aspects of their life that make them feel (un)certain about themselves, their lives, and their future, and then to write a few sentences about the three aspects that make them feel most (un)certain (Hogg et al., 2007). This prime and minor variants, for example a focus on feeling (un)certain about themselves, their future, or their place in the world, has been used effectively in scores of studies (e.g., Grant & Hogg, 2012; Hohman & Hogg 2015; Hohman et al., 2017). Self-uncertainty has been measured in multiple ways involving a single self-uncertainty item or multi-item scales focusing on self, personality, relationships, place in society, and so forth (e.g., Hohman & Hogg, 2015; Hohman et al., 2017; Rast, Gaffney, Hogg, & Crisp, 2012; Rast et al., 2013).

Implicit to these self-uncertainty primes and measures is recognition that “self” is multifaceted (e.g., Swann & Bosson, 2010) and that different domains of self can be more or less overlapping with or discrete from one other (self and identity complexity: e.g., Brewer & Pierce, 2005; Grant & Hogg, 2012; Linville, 1987; Roccas & Brewer, 2002). Also implicit, and drawing on these ideas, is an uncertainty-identity theory tenet that uncertainty relating primarily to one aspect of self can affect other aspects of self, there is often a halo effect. Furthermore, in the absence of alternative ways to reduce uncertainty (e.g., through self-affirmation; see Sherman & Cohen, 2006), group identification can very effectively reduce self-uncertainty, largely irrespective of specific self-focus of the uncertainty but most markedly if the self-focus is on the collective social identity-related self.

1.2 The present research

The aim of the present research was to explore these ideas further to distinguish between different domains of self-uncertainty (Study 1) and then examine their relative impact on group identification (Study 2). Our argument proceeds from Brewer and Gardner's (1996; cf. Brewer, 2001; Brewer & Chen, 2007; Chen, Boucher, & Tapias, 2006; Sedikides & Brewer, 2001) distinction between three different aspects of self: (a) the individual self, based on personal traits that differentiate the self from all others; (b) the relational self, based on connections and role relationships with significant others, and (c) the collective self, based on group membership that differentiates “us” from “them.”

We expected that feelings of self-uncertainty would largely reflect this structural differentiation of self. Feelings of uncertainty about one's individuated self based on personal attributes, feelings of uncertainty about one's self as defined by relationships with specific others, and uncertainty about one's collective self as defined by one's group memberships and social identities would be independent but very likely correlated to some degree with one another. Study 1, which to some extent served as a pilot for Study 2, was a measurement study that explored this expectation. We then went on to predict that uncertainty related to the collective self would be a stronger predictor of group identification than either individual or relational self-uncertainty. Study 2 tested this prediction in an experiment where we manipulated each of the three domains of uncertainty established by Study 1, and measured effects on identification.

2 STUDY 1

Study 1 explored the structure of self-uncertainty by administrating a questionnaire measuring dimensions of self-uncertainty. Although, Study 1 was largely exploratory, we anticipated discovering that three distinct but correlated dimensions of self-uncertainty would emerge to make the most meaningful sense of the data—individual, relational, and collective self-uncertainty.

3 METHODS

3.1 Participants and procedure

Participants (N = 140) were recruited across a variety of community settings in Southern California. This satisfied the 5 to 10 participants per variable (there were 20 variables—see below) rule of thumb for exploratory factor analysis, and produced the relatively representative sample we were hoping for. There were 54 males and 86 females, who ranged in age from 18 to 69 (Mage = 33.26, SD = 12.85). The majority self-identified as Caucasian (59.3%), Hispanic (16.4%), or Asian (11.4%). Very few self-identified as African American (.07%) or Native American/Pacific Islander (.07%), and the remaining participants did not respond (2.1%) or wrote-in an identity that was not clearly related to ethnicity (9.3%).

Prospective participants were approached at beaches, farmers' markets, and softball games by two female researchers and asked to participate in a short 10-min paper–pencil survey assessing what makes people uncertain about themselves. They read and signed an informed consent form, completed a questionnaire, and then provided demographic information (sex, age, and ethnicity). Responses were anonymous and confidential, and completed questionnaires were placed in a sealed envelope in the presence of the respondent.

3.2 Measures

The questionnaire presented a list of 22 self-attributes and domains (all presented as “Your …”; e.g., “Your career,” “Your sense of humor”) and participants were asked to indicate for each how certain they felt about it and how important they felt it was to them, 1 not very much, 9 very much. We measured subjective importance because a key tenet of uncertainty identity theory is that it is only uncertainties that are subjectively important that motivate uncertainty reduction and thus group identification (Hogg, 2007).

The attributes and domains focused on careers, education, personality attributes, and so forth (see Table 1). To make the task more meaningful, concrete examples were provided for some of the items. The majority of these domains (particularly those related to personality) have been successfully used in previous research to measure uncertainty (e.g., Hogg et al., 2007). A number of additional domains (e.g., career, education) were chosen as relevant on the basis of a qualitative pilot study in which people were asked to talk about things that made them feel uncertain about themselves, their place in the world, and their future.

| Importance | Certainty | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Item | M | SD | M | SD |

| Sports competency | 5.07 | 2.39 | 5.78 | 2.18 |

| Artistic ability | 5.28 | 2.43 | 5.42 | 2.33 |

| Sex appeal | 6.34 | 2.03 | 6.41 | 1.84 |

| Place in society | 6.43 | 1.86 | 6.47 | 1.65 |

| Physical attractiveness | 6.50 | 1.80 | 6.30 | 1.66 |

| Professional relationships | 6.91 | 1.71 | 6.58 | 1.63 |

| Leadership ability | 7.14 | 1.63 | 6.88 | 1.59 |

| Trust in others | 7.21 | 1.73 | 6.22 | 1.90 |

| Sense of humor | 7.57 | 1.55 | 7.38 | 1.58 |

| Social skills | 7.63 | 1.45 | 7.07 | 1.78 |

| Finances | 7.64 | 1.49 | 5.89 | 2.06 |

| Common sense | 7.68 | 1.30 | 7.27 | 1.37 |

| Career | 7.74 | 1.72 | 6.24 | 2.12 |

| Responsibilities | 7.79 | 1.43 | 7.27 | 1.58 |

| Emotional stability | 7.81 | 1.32 | 6.99 | 1.72 |

| Morality | 7.81 | 1.62 | 7.61 | 1.46 |

| Education | 8.10 | 1.26 | 7.40 | 1.71 |

| Goals | 8.10 | 1.11 | 6.77 | 1.70 |

| Independence | 8.12 | 1.10 | 7.37 | 1.55 |

| Health | 8.12 | 1.38 | 6.70 | 1.95 |

| Intellectual ability | 8.24 | 1.03 | 7.32 | 1.31 |

| Personal relationships | 8.61 | 1.02 | 7.62 | 1.53 |

Note

- Items are listed in order of increasing subjective importance. Scale anchors are 1 not very much, 9 very much. The number of responses on each item range from 120 to 140.

4 RESULTS

4.1 Structure of self-uncertainty

Table 1 lists the 22 items (self-attributes and domains) and the mean importance and certainty scores along with their SDs. Examination of importance scores revealed that two items (sports competency and artistic ability) were considered significantly less important to self (Ms of 5.07 and 5.28) than the other 20 items (the next lowest rated item had a mean importance rating of 6.34, and the most subjectively important item was rated 8.61). In addition, these two items did not differ significantly, by one-sample t test, from the scale midpoint (ps > .18) whereas all other items did differ significantly from the scale midpoint (ps < .001). Because sports competency and artistic ability were significantly less subjectively important to self-conception they were excluded from subsequent analyses.

The remaining 20 self-attributes and domains were factor analyzed—exploratory factor analysis with principle axis factoring and direct oblimin rotation. Six factors with eigenvalues greater than unity emerged. Inspection of the scree plot indicated that four of these factors stood relatively clear of the scree. Rotation was performed on these four factors and rotated factor loadings greater than 0.40 were used to interpret the factors. Table 2 shows eigenvalues and percentage of variance accounted for by each factor, and rotated factor loadings on constituent items (only factor loadings >0.40 are shown). The inter-factor correlation matrix indicated that F1 was correlated with F2 (r = .258) and F4 (r = −.331) and F2 was correlated with F4 (r = −.202). All other correlation coefficients were less than 0.20.

| Factor 1 | Factor 2 | Factor 3 | Factor 4 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| (5.43) | (2.01) | (1.84) | (1.49) | |

| Item | (27.13%) | (10.04%) | (9.21%) | (7.46%) |

| Independence | 0.709 | – | – | – |

| Intellectual ability | 0.663 | 0.468 | – | – |

| Career | 0.639 | – | – | – |

| Responsibilities | 0.636 | – | 0.490 | – |

| Finances | 0.583 | – | – | – |

| Leadership ability | 0.573 | – | – | – |

| Sex appeal | – | 0.836 | – | – |

| Physical attractiveness | – | 0.807 | – | – |

| Social skills | – | 0.596 | 0.591 | – |

| Health | – | 0.556 | – | – |

| Place in society | 0.421 | 0.535 | – | – |

| Professional relationships | – | 0.487 | – | – |

| Trust in others | – | – | 0.704 | – |

| Sense of humor | – | – | 0.555 | – |

| Personal relationships | – | – | – | 0.811 |

| Emotional stability | 0.437 | – | – | 0.792 |

| Morality | – | – | – | 0.717 |

| Goals | 0.515 | – | – | .645 |

| Education | 0.403 | – | – | .560 |

| Common sense | – | – | – | .557 |

Note

- Only factor loadings >0.40 are shown.

Inspection of the rotated factor loadings shown in Table 2 suggests that Factor 1 represents a sense of self located in the wider world of work and society—a focus on the category-based (collective) self. Factor 2 represents individual physical and social attributes of self but in societal context—a focus on the individual self. Factors 3 and 4 both seem to reflect the relational self, but in slightly different ways. Factor 3 represents sociability—a focus on the individual self but perhaps more strongly the relational self. Factor 4 represents self in close relationships, and attributes that are important to such relationships—clearly a focus on the relational self.

4.2 Gender and age differences in importance and certainty judgments

A final set of analyses investigated gender and age differences in importance and certainty evaluations of the four factors. We first computed mean importance and certainty scores across the high loading items for each factor: Factor 1 (10 items; α = 0.76 and 0.82 for importance and certainty), Factor 2 (7 items; α = 0.74 and 0.76 for importance and certainty), Factor 3 (4 items; α = 0.64 and 0.65 for importance and certainty), and Factor 4 (6 items; α = 0.62 and 0.80 for importance and certainty). We then performed a one-way (participant sex) ANOVA on each of the eight composite importance and certainty measures. All effects were nonsignificant (Fs < 2.52, ps > .115), except one—females placed greater importance on self defined in terms of personal relationships (Factor 4) than did males (Ms = 8.14, 95% CI [7.97, 8.30] and 7.84, 95% CI [7.63, 8.05], F(1, 133) = 4.91, p = .028, ɳ2 = 0.04).

We also ran a series of bivariate correlations between age and each of the eight composite importance and certainty measures. Five of these were significant. Older participants placed significantly greater importance on self defined in terms of personal relationships (Factor 4) than did younger participants (r = .22, p = .012), and older participants also felt more certain about themselves than did younger participants on all four self-dimensions—Factor 1 (r = .25, p = .009), Factor 2 (r = .19, p = .029), Factor 3 (r = .28, p = .001), and Factor 4 (r = .26, p = .002).

5 DISCUSSION

Study 1 explored the structure of self-uncertainty by having participants rate 22 self-attributes and dimensions in terms of how important they felt they were to them and how certain they were about them. Two items were subsequently excluded from analysis because they had markedly low subjective importance ratings. Certainty ratings of the remaining 20 self-items were explored factor-analytically. On the basis of previous research (e.g., Brewer & Gardner, 1996), we anticipated a tripartite structure reflecting three distinct but intercorrelated domains of self: individual, relational, and collective self.

What we found was largely consistent with this, but not a perfect fit. Four distinct but intercorrelated aspects of self-uncertainty emerged: One (Factor 1) reflected self located in the wider world of work and society—resembling the collective self; one (Factor 2) reflected individual physical and social attributes of self but in societal context—resembling the individual self; one (Factor 4) reflected self in close relationships, and attributes important to such relationships—clearly resembling the relational self; and one (Factor 3) reflecting sociability—resembling both the individual and relational self.

That we found four factors, among which two (Factors 3 and 4) represent different aspects of the relational self, is not surprising. Although the relational self is largely an interpersonal form of self, it has been suggested that it may break into two components; one representing self in true close interpersonal relationships, and the other representing self in relation to specific other individuals with whom one interacts in a group context (Brewer, 2001; Chen et al., 2006). The latter could be considered a particular type of collective self where groups are to some extent defined in terms of networks of relationships (e.g., Seeley, Gardner, Pennington, & Gabriel, 2003; Yuki, 2003).

Although not central to the purpose of Study 1, we were interested to see if the two key demographic variables of gender and age impacted importance and certainty ratings on each of the four self-dimension. We found that women placed greater importance on self defined in terms of personal relationships (Factor 4) than did males, which is consistent with a long tradition of research and data on gender differences (e.g., Wood & Eagly, 2010); and that older participants felt more certain about themselves than did younger participants on all four self-dimensions, which is consistent with lifespan developmental research showing that as people get older they typically become less uncertain about themselves and develop a more clearly defined sense of self (see Labouvie-Vief, Chiodo, Goguen, Diehl, & Orwoll, 1995; McAdams & Cox, 2010).

6 STUDY 2

The results of Study 1 lay the foundation for Study 2 in so far as they largely support the expectation that self-uncertainty can be experienced in three distinct domains of self that are somewhat correlated such that uncertainty in one domain may to varying degree bleed over to affect other domains. However, from an uncertainty-identity theory perspective the clear expectation is that self-uncertainty related to the collective self will be a stronger predictor of group identification than self-uncertainty related to individual or relational self—social categorization of self and others engages and reduces uncertainty about social identity and the collective self (Hogg, 2007, 2012).

Study 2 set out to explore this expectation by experimentally manipulating individual, relational and collective self-uncertainty independently and measuring effects on group identification. It was hypothesized that there would be an overall main effect of uncertainty on identification (H1), but that this main effect would be moderated by aspect of self such that the effect would be most pronounced, or only emerge, on collective self (H2).

7 METHODS

7.1 Participants and design

Participants were American residents over the age of 18 recruited via Amazon's Mechanical Turk, which has been shown to be a valid and reliable source of data (e.g., Buhrmester, Kwang, & Gosling, 2011; Mason & Suri, 2012). There were 382 participants—a prior power analysis signaled that we needed 210 participants for a medium difference (d = 0.30) and power of 0.80 between six groups (Cohen, 1992). Of the 382 participants, 142 (36.9%) were male and 241 (63.1%) female, and the overwhelming majority self-identified as Caucasian (274, 71.7%) with very small proportions of Asians (25, 6.5%), African Americans (22, 5.8%), and Hispanics (13, 3.4%). The age distribution was relatively even across the age groups of 18–24 (94, 24.6%), 25–34 (126, 33.0%), and 35–54 (124, 32.5%), with only a small number over the age of 55 (38, 9.9%).

The experiment had two independent variables manipulated in a 3 (aspect of self: individual, relational, collective) × 2 (uncertainty: low, high) orthogonal design, across which participants were randomly distributed. There was one multi-item dependent measure—group identification.

7.2 Procedure

This general type of “hypothetical/imagined group” paradigm has been used successfully in many previous social identity and uncertainty-identity theory studies (e.g., Hogg et al., 2007).We are interested in learning about how people interact and identify with different groups. What we will be doing is forming a number of small groups (6 to 7 members) on Mechanical Turk to discuss various topics. We want the groups to be as focused, cohesive, and compact as possible; so the people in the groups will be specifically and carefully chosen to be as similar as possible in terms of age, attitudes, religion, and social and ethnic backgrounds, etc. In order to predict how our group members might feel about being a member of one of these groups, we want you to imagine that you are one of the members randomly chosen. Take some time to think about the group and what it would be like to be in this group yourself. Imagine what the group is like, how the members interact, how similar people are to yourself, etc.

Self-uncertainty was now manipulated using a priming procedure that has been used successfully in various forms in scores of studies (e.g., Grant & Hogg, 2012; Hogg et al., 2007; Hohman & Hogg, 2015; Hohman et al., 2017). Participants were asked to “take a few minutes to think about those aspects of your life that make you feel uncertain about yourself in relation to [uncertainty domain here]. List the three that make you feel most uncertain.” Specifically, depending on self-aspect condition, they were asked to describe things related to “your personality and/or yourself as an individual” (individual self), “your relationships” (relational self), or “your society and/or the groups you belong to” (collective self). Those in the low uncertainty conditions were asked to answer the same questions with the word “uncertain” replaced with “certain.”

Group identification was now measured with seven items selected and adapted from measures used successfully over the past 25 years in previous social identity studies (e.g., Hains, Hogg, & Duck, 1997; Hogg & Hains, 1996; Hogg, Hains, & Mason, 1998). Participants were asked to actively imagine being a part of the group they read about earlier and indicate how much they would (a) identify with, (b) feel committed toward, (c) like, (d) feel favorable toward, (e) belong to, and (f) fit in with the group, as well as (g) how important the group would be to their sense of self if they were chosen to join; 1 not very much, 9 very much, α = 0.91.

Participants now provided demographic information (gender, age group, and ethnicity), were debriefed, and the study was concluded.

8 RESULTS

A precautionary 3 (aspect of self) × 2 (uncertainty) MANOVA on gender and age group revealed no significant effects (multivariate and associated univariate Fs < 1.92, ps > .167)—indicating no confound between condition and age or gender.

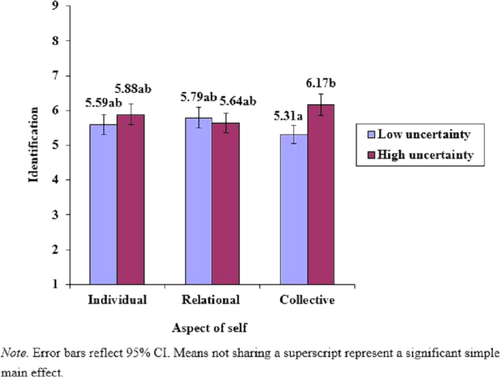

Our focal analysis was a straightforward 3 × 2 ANOVA on mean identification. As predicted under H1 there was a significant main effect for uncertainty, F(1, 376) = 4.77, p = .030, ɳ2 = 0.01)—uncertainty strengthened identification (Ms = 5.56, 95% CI [5.35, 5.78] and 5.89, 95% CI [5.69, 6.10]. However, exactly as predicted under H2, this effect was moderated by aspect of self, F(2, 376) = 3.60, p = .028, ɳ2 = 0.02)—see Figure 1. The simple effect of uncertainty was significant on collective, F(1, 376) = 10.09, p = .002, ɳ2 = .03, but not individual or relational self (Fs < 1.24, ps > .266). Neither simple main effect of aspect of uncertainty was significant (Fs < 2.00, ps > .138).

Study 2: Identification as a function of uncertainty and aspect of self, F(2, 376) = 3.60, p = .028, ɳ2 = 0.02

9 DISCUSSION

Building on the finding from Study 1 that self-uncertainty can be structured into three distinct but overlapping domains (individual, relational, and collective self). Study 2 manipulated uncertainty separately on each of these three dimensions. As predicted and replicating scores of earlier uncertainty-identity theory studies, uncertainty significantly strengthened group identification (H1). The aim of Study 2 was to show something that has not been empirically shown before, that this effect would be moderated by aspect/dimension of self-uncertainty such that it would be stronger or only present in the context of collective identity uncertainty (H2). This hypothesis was supported—uncertainty strengthened group identification only when it was collective self-uncertainty, not individual or relational self-uncertainty.

10 GENERAL DISCUSSION

Social psychologists have long considered various forms of uncertainty and uncertainty-related reduction to be an important motivation for human behavior. Among these, uncertainty-identity theory has recently focused specifically on the relationship between self and self-related uncertainty on group identification (e.g., Hogg, 2007, 2012). Self-uncertainty, which is often disconcerting and maladaptive, is very effectively resolved by the process of social categorization and associated group identification and prototype-based depersonalization of self and others described by social identity theory (Turner et al., 1987). Uncertainty-identity theory research has repeatedly found that self-uncertainty does strengthen group identification, particularly with groups whose properties (e.g., entitativity) are best suited to providing a distinctive and clearly defined identity.

One assumption of uncertainty-identity theory is that uncertainty motivates identification largely irrespective of what aspect of self is the primary focus of the uncertainty (self-uncertainty in one domain bleeds across to affect other domains)—though collective/social identity-related self-uncertainty is assumed to more strongly motivate group identification. Research has directly or indirectly manipulated or measured self-uncertainty in many different ways—ways that do not differentiate between different aspects of self. The present research is the first to actually empirically tease apart different domains of self-uncertainty to investigate their relative impact on identification. In this respect, the research speaks to an important, and as yet untested, assumption of uncertainty-identity theory.

Drawing primarily on Brewer and Gardner's (1996) broad distinction between the individual, relational, and collective self, Study 1 measured self-uncertainty relating to an array of important attributes and aspects of self, with the expectation that they would cluster into these three distinct but overlapping domains. Factor analytic techniques largely supported this tripartite structure, although the fit was not perfect. One factor captured a sense of self located in the wider world of work and society—a focus on the category-based (collective) self; a second factor captured individual physical and social attributes of self but in societal context—a focus on the individual self. The relational self was represented by two factors that embodied slightly different aspects of the relational self (cf. Brewer, 2001; Chen et al., 2006): one captured sociability and the relational self, and the other captured the relational self as it loaded on self in close relationships, and attributes that are important to such relationships.

In Study 2, we experimentally manipulated uncertainty separately for each of these three dimensions of self—individual, relational, collective. Reflecting the somewhat overlapping nature of these three aspects of self-uncertainty we predicted (H1) and found a main effect for uncertainty irrespective of the domain of self-uncertainty—a finding that replicates previous uncertainty-identity theory research where domain of self was not dissociated. However, we also hypothesized that because collective self is more closely related to group identification, domain would moderate this effect (H2). This is what we found—domain moderated the uncertainty effect such that it was only significant for the collective self.

One possible limitation of Study 2 is the “hypothetical/imagined group” paradigm. This is a standard paradigm in social identity and uncertainty-identity research (e.g., Hogg et al., 2007), but it is relatively low in identity realism, and in Study 2 in particular it effectively draws all participants' attention to the collective before they have their individual, relational, or collective self primed. To complement Study 2's findings future research might administer the uncertainty primes as in Study 2 but at the outset, and then measure contextual identification with social categories that the participants actually already belong to (e.g., religion, political party, nation).

Overall, the research reported in this article not only provides support for a significant and previously untested assumption of uncertainty-identity theory, but also suggests some implications. There is a clear halo effect in which uncertainty within one domain of self bleeds over, to some extent, to other domains. For example, self-uncertainty related primarily to one's relationships may also make one feel a little uncertain about one's social identities. However, what remains to be researched is just how much uncertainty transfer is possible, facilitating and inhibiting conditions, and the extent to which transfer is bi-directional or not—for example, is it more likely for collective self-uncertainty to create relational self-uncertainty, or vice versa?

As expected collective self-uncertainty (tied to a person's location and identity in wider society) is a stronger motivator of group identification than is individual or relational self-uncertainty, however, group identification may also serve as a potential, but perhaps limited, palliative for individual and relational uncertainties. In this respect, people may identify with groups (e.g., community/recreational groups, political/religious groups, etc.) to resolve relationship-based self-uncertainties stemming from, for example, betrayal, divorce, bereavement, loneliness, and so forth.

One potential downside of group identification to address relational or individual self-uncertainty is that people may become vulnerable to the appeal of extremist ideologies, groups, and identities and to populist leadership (cf. Hogg, 2014). They may become ripe for radicalization. For example, adolescents struggling with changing relationships with their family and friends and uncertain about what kind of a person they are may be drawn to self-relevant religious or political extremism or to available gangs or youth subcultures that engage in risky behaviors (e.g., Goldman, Giles, & Hogg, 2014; Hogg et al., 2010; Hogg, Siegel, & Hohman, 2011).