Cow's milk protein allergy with protein-losing enteropathy under the scope

ABSTRACT

Objectives

Cow's milk protein allergy (CMPA) is very frequent in infants. Presentation is variable, and symptoms fluctuate in intensity. Diagnosis can be challenging as it is mostly clinical. In severe cases, patients can present with anasarca secondary to protein-losing enteropathy (PLE). The exact mechanism underlying PLE is incompletely understood. Here we report four cases of severe PLE caused by CMPA warranting endoscopic workup in whom histological expression was characterized by variable features along the gastrointestinal (GI) tract.

Methods

We report four cases of severe CMPA with PLE requiring extensive workup including endoscopy to exclude immune deficiency or congenital enteropathy. The different histological expressions along the GI tract are presented.

Results

Histology ranged from the expected eosinophilia, observed in all cases, to severe mucosal atrophy with subtotal loss of colonic glands. Correlation between endoscopy and histology was poor.

Conclusion

CMPA can affect any segment of the GI tract and the intensity of the histological findings varies among patients and localizations. Food protein allergy should be considered in infants and children with hypoalbuminemia.

Highlights

What Is Known?

-

Cow's milk protein allergy (CMPA) is essentially a clinical diagnosis with only rare histological descriptions.

-

Poor correlation between endoscopy and histology.

-

No pathognomonic endoscopical or histological findings.

What Is New?

-

Protein-losing enteropathy may be due to CMPA only.

-

Trial of cow's milk protein (CMP) elimination as initial step.

-

CMP exclusion may allow for histological remission despite initial severe findings.

1 INTRODUCTION

Cow's milk protein allergy (CMPA) is the most common food allergy in infants and young children, and can present with a diverse range of symptoms.1 Immunological mechanisms in CMPA may be either immunoglobulin E (IgE)- and non-IgE-mediated: allergies to cow's milk protein (CMP) have in common symptom improvement after CMP elimination and symptom recurrence after CMP reintroduction.1, 2 Non-IgE-mediated gastrointestinal food-induced allergic disorders (non-IgE-GI-FAs) include food protein-induced enteropathy (FPE), food protein–induced enterocolitis syndrome (FPIES), and food protein-induced allergic proctocolitis (FPIAP).2 FPE predominantly affects the small bowel, while FPIES can affect the entire gastrointestinal (GI) tract and FPIAP affects the distal colon and rectum.2

FPIES and FPE most commonly present with vomiting, diarrhea, and failure to thrive (FTT).1 FPIAP presents with bloody stools. In severe cases, patients can present with anasarca secondary to protein-losing enteropathy (PLE) with an excessive loss of serum proteins (albumin, gammaglobulin) into the GI tract as seen in FPIES and FPE.3 CMPA diagnosis is based on clinical features and symptom recurrence upon oral food challenge.2 In rare cases, severe CMPA can raise concern for congenital enteropathy or immune deficiency indicating endoscopic workup. As endoscopy is rarely needed in general practice histological descriptions of CMPA are scant. The exact mechanism underlying PLE is incompletely understood. Here, we report four cases of severe PLE caused by CMPA warranting endoscopic workup in whom histological expression was characterized by variable features along the GI tract. Withdrawal of the offending food led to disappearance of symptoms even in the most severe case.

2 METHODS

Clinical evaluation and follow-up, upper- and lower-endoscopy, and histological analysis were performed in all four cases at our institution between 2012 and 2016. However, the young age and clinical state of the patients did not allow for complete upper and lower endoscopy in all patients. Videocapsule endoscopy was performed in one patient.

Four to six 3-μm-thick sections of formalin-fixed paraffin-embedded endoscopic biopsies were stained with hematoxylin-eosin (H&E), and special stains were applied according to biopsy location (PAS in the duodenum and esophagus, modified Giemsa stain in the stomach). Lymphatics were highlighted by immunohistochemistry, using the mouse anti-human D2–40 immunostain (Dako, clone D2–40, 1:50). In selected cases, CD3 (Novocastra mouse monoclonal, clone 17C2; dilution 1:20), and CD20 (CellMarque mouse monoclonal, clone 1G12; dilution 1:20) were used to characterize T and B lymphocytes respectively.

Tissue eosinophil counts were performed on scanned H&E slides and were compared to the previously reported quantity of eosinophils in the GI tract of children with no histological anomalies.4, 5 Peak counts of eosinophils were reported per high power field (HPF, 0.196 mm2); eosinophilic infiltration was also reported as numbers of cells per square millimeter (eosinophils/mm2).

2.1 Ethics statement

Parental consent for publication was obtained. This study was considered as falling outside of the scope of the Swiss legislation regulating research on human subjects, so that the need for local ethics committee approval was waived.

3 RESULTS

Main endoscopy and histology findings at initial presentation are summarized in Table 1, and patient characteristics in Table S1.

| Esophagus | Stomach | Duodenum | Ileum | Colon | Rectum | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| P1 | Endoscopy | Normal | Normal | Edema | Edema | Normal | Edema |

| Architecture | NA | NA | Normal | Normal | Normal | Normal | |

| Eosinophils | NA | NA | 25/HPF, 97/mm2 | 15/HPF, 37/mm2 | Caecum 11/HPF, 37/mm2 Ascending 27/HPF, 87/mm2 Transverse 15/HPF, 74/mm2 Descending 31/HPF, 97/mm2 Sigmoid 25/HPF, 67/mm2 |

46/HPF, 137/mm2 | |

| Other | - | - | Rare PMNs, vacuolated enterocytes | - | Rare PMNs | - | |

| P2 | Endoscopy | Normal | Normal | Normal | NA | Normal | Normal |

| Architecture | Normal | Normal | Nonevaluable | NA | Major dystrophy, gland loss, vanishing glands | NA | |

| Eosinophils | *6/HPF, 9/mm2 | Antrum 26/HPF, 73/mm2 Fundus 95/HPF, 269/mm2 |

63/HPF, 195/mm2 | NA | Ascending 66/HPF, 209/mm2 Transverse 204/HPF, 393/mm2 Descending 144/HPF, 469/mm2 |

NA | |

| Other | - | Rare PMNs, rare apoptosis | PMNs, gland abscesses, apoptosis | - | PMNs in residual glands, apoptosis | - | |

| E2, +1m | Endoscopy | Normal | Normal | Normal | NA | Normal | Normal |

| Architecture | Normal | Normal | Chronic duodenitis, villous atrophy, gastric metaplasia | NA | Focal gland loss, dystrophy, regeneration | NA | |

| Eosinophils | 0 | Antrum 0 | 84/HPF, 157/mm2 | NA | Descending 119/HPF, 335/mm2 | NA | |

| Other | - | Edema | Few PMNs, apoptosis | - | Few PMNs, apoptosis | - | |

| E3, +11m | Endoscopy | Normal | Normal | Normal | NA | Normal | Normal |

| Architecture | N | Regeneration, edema | NA | Dystrophic surface epithelium, bifid glands | |||

| Eosinophils | *2/HPF, 3/mm2 | Antrum 7/HPF, 12/mm2 Fundus 5/HPF, 8/mm2 |

21/HPF, 59/mm2 | NA | Descending 23/HPF, 100/mm2 | 24/HPF, 67/mm2 | |

| Other | - | Edema | Edema | - | Rare PMNs, apoptosis, edema | ||

| P3 | Endoscopy | Normal | Normal | Normal | Alternance of linear ulcers and pale zones, villous atrophy, edema (vidéocapsule) | Edema | Normal |

| Architecture | Normal | Normal | Normal | Normal | Normal | Normal | |

| Eosinophils | 0 | Antrum 75/HPF, 144/mm2 Fundus 36/HPF, 222/mm2 |

90/HPF, 191/mm2 | 76/HPF, 173/mm2 | Caecum 60/HPF, 225/mm2 Ascending 63/HPF, 186/mm2 Transverse 38/HPF, 213/mm2 Descending 56/HPF, 117/mm2 Sigmoid 28/HPF, 107/mm2 |

32/HPF, 125/mm2 | |

| Other | - | - | - | - | Apoptosis | - | |

| P4 | Endoscopy | Normal | Normal | Normal | NA | Normal (left colon only) | Normal |

| Architecture | NA | Normal | Normal | NA | Normal | Normal | |

| Eosinophils | NA | Antrum 12/HPF, 29/mm2 Fundus 20/HPF, 49/mm2 |

46/HPF, 185/mm2 | NA | Descending 14/HPF, 34/mm2 Sigmoid 20/HPF, 59/mm2 |

28/HPF, 68/mm2 | |

| Other | - | - | - | - | - | - | |

| Ref Eo# | DeBrosse et al. [4] | 0.03 ± 0.10/HPF | Antrum <8 (1.9 ± 1.3/HPF) Fundus <9 (2.1 ± 2.4/HPF) |

<26 (9.6 ± 5.3/HPF) | <28 (12.4 ± 5.4/HPF) | Caecum 15.4 (10.2–18/HPF) Transverse colon 16.3 ± 5.6/HPF Sigmoid <42 (8.3 ± 5.9/HPF) |

<32 (8.3 ± 5.9/HPF) |

| Koutri et al. [5] | 0/HPF, 0/mm2 | 2 (1–3/HPF), 10.2 (5.1–15.3/mm2) | 12 (6.3–15/HPF), 61.2 (31.9–76.5/mm2) | 12 (9.6–15/HPF), 61.2 (31.9–76.5/mm2) | Caecum 15.4 (10.2–18/HPF), 78.4 (51.9–91.8/mm2) Ascending 13.5 (12.8–17.5/HPF), 68.9 (65.1–89.3/mm2) Transverse 13 (8–19/HPF), 66.3 (40.8–97.1/mm2) Descending 13 (9.3–15/HPF), 66.3 (47.2–76.5/mm2) Sigmoid 8 (5.1–11/HPF), 40.8 (26.1–56.1/mm2) |

5 (1.9–7.8/HPF), 25.5 (9.8–40/mm2) | |

- Note: In red: increased eosinophilic infiltration, according to ≥1 ref. Abbreviations: HPF, high power field (×400; 0.196 mm2); NA, no data available; PMN, polymorphonuclear neutrophil; Ref Eo#, reference numbers of eosinophils: median (interquartile range).

3.1 Patient 1: A 4-month-old breast-fed infant with diarrhea and vomiting

A 4-month-old boy, strictly breastfed from a mother ingesting cow's milk, presented with a history of non-bloody diarrhea for 12 days, postprandial vomiting and generalized edema. FTT was noticed for 2 weeks prior. The patient presented to our institution with anasarca. Laboratory results revealed severe hypoalbuminemia and hypogammaglobulinemia. Increased stool alpha-1-antitripsyn (A1AT) was indicative of protein loss in the stool. GI infection was ruled out and there was no proteinuria. Endoscopy showed mucosal edema in the duodenum, ileum, and rectum. Histology showed normal architecture in all assessed locations (duodenum, ileum, and colon). Active inflammation was minimal, with rare neutrophils infiltrating the epithelium, in the duodenal bulb and the cecum. Eosinophils were increased in the lamina propria of the duodenum, descending colon, sigmoid, and rectum (Table 1). The duodenum showed vacuolated enterocytes. Mild lymphatic dilatation was seen in the duodenal villous axis upon immunohistochemical evaluation (D2–40). Clinical improvement was observed within 10 days after initiation of parenteral nutrition (PN) followed by progressive introduction of an enteral nutrition with an extensively hydrolyzed formula. FTT resolved after 12 months' elimination, and there was no symptom recurrence or evidence of enteropathy upon CMP reintroduction. At the time of consent, Patient 1 was 6 years old and doing well.

3.2 Patient 2: A partially breast-fed 7-week-old infant with bloody stools and vomiting

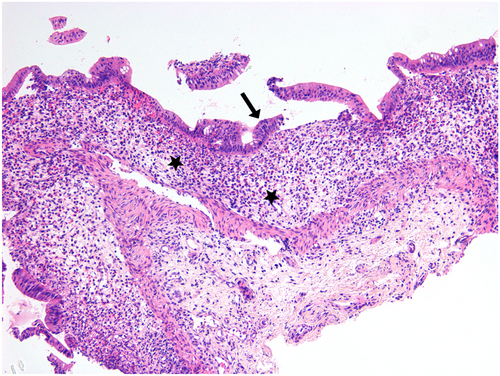

A 7-week-old girl presented with postprandial vomiting and persistent bloody diarrhea from the age of 1 month. She was breast-fed from a mother ingesting cow's milk and occasionally received infant formula since birth. She had developed FTT from 4 weeks of life. As diarrhea persisted during fasting, PN was initiated. Clinical exam only showed moderate dehydration. Laboratory explorations revealed hypoalbuminemia and hypogammaglobulinemia. Stool A1AT was not checked. GI infection was ruled out and there was no proteinuria. Endoscopy was macroscopically normal. Histological features were particularly striking in the colon, showing subtotal gland loss with surface epithelium dystrophy and rare neutrophilic infiltrate, edema, and increased eosinophils in the lamina propria (Figure 1). A sparse lymphocytic infiltrate was mainly composed of CD3-positive T cells. The esophagus and stomach showed no architectural changes. The fundus showed increased lamina propria eosinophils and edema, and few apoptotic bodies (2 in 10 consecutive glands) (Table 1). Architecture was difficult to assess in the duodenum, but focal active duodenitis with a gland abscess was seen. Diarrhea resolved within 18 days of PN. Breastmilk with CMP was reintroduced while the patient was still on PN, and symptoms recurred. She was then started on extensively hydrolyzed formula. Because of the severe symptoms at presentation and of the histological findings, repeat endoscopy was performed 1 month after the initial biopsies. Upper GI histology showed chronic active duodenitis, with partial villous atrophy, fused glands, and regeneration; apoptotic bodies were increased (up to 5 in 10 consecutive glands), and eosinophils were more numerous in areas with active neutrophilic duodenitis (Figure S1). Repeat endoscopy performed 11 months after the initial biopsies, revealed only mild surface epithelium dystrophy and rare bifid glands (Figure S2). Withdrawal of the offending food allowed for histological mucosal restoration. Lymphocytic infiltration was sparse in the lamina propria, and CD20-positive B lymphocytes were more numerous than the CD3-positive T cells. Duodenal architecture was restored, with only focal regenerative changes and lamina propria edema. Immunohistochemistry (D2–40) showed mild lymphatic dilatation. The patient remained asymptomatic after 15 months of CMP elimination, and CMP were reintroduced. At the time of consent, Patient 2 was 9 years old and doing well.

3.3 Patient 3: A 2-year-old “big cow's-milk drinker” with palpebral edema

A 27-month-old boy with a history of daily bilateral palpebral edema since the age of 1 year presented with a 2-month history of lower limb edema and no GI symptoms. At time of diagnosis, the child was on an age-appropriate solid food diet and enjoying one liter of cow's milk daily. Clinical exam confirmed palpebral and lower limb nonpitting edema. Laboratory investigations revealed hypoalbuminemia and hypogammaglobulinemia. Stool A1AT was increased. GI infection was ruled out and there was no proteinuria. Video-capsule endoscopy revealed active bleeding, linear ulcerations alternating with pale zones throughout the small bowel, suggesting villous atrophy (Figure 2). Histology showed normal architecture, both in the upper- and lower-endoscopy specimens. Increased lamina propria eosinophils were seen in the stomach, reaching the numbers of 75/HPF in the antrum, whilst sparing the epithelium (Figure 3), in the duodenum, in the colon, and in the rectum (Table 1). Again, mild lymphatic dilatation was observed. Symptoms resolved within 8 days of initiating a CMP elimination diet and a partially hydrolyzed formula. As there was no recurrence of symptoms or evidence of enteropathy after 1 year of dietary elimination, CMP were reintroduced. At the time of consent, Patient 3 was 8 years old and doing well.

3.4 Patient 4: A baby with puffy eyes

A 13-month-old girl presented with a 6-day history of palpebral and lower limb pitting edema and a recent weight gain of 900gr without GI symptoms. At time of diagnosis, she was on an age-appropriate diet including cow's milk and other dairy products. Laboratory studies revealed hypoalbuminemia and hypogammaglobulinemia. Stool A1AT was increased. GI infection was ruled out and there was no proteinuria. Endoscopy was normal. Histology showed normal architecture in the upper GI biopsies, with mild chronic pangastritis, but no activity or Helicobacter pylori infection; eosinophils were also increased in the stomach, duodenum, sigmoid, and rectum (Table 1). Architecture was more difficult to assess in the left colon, due to crush artifacts, but appeared normal in the sigmoid and rectum. Mild lymphatic dilatation was observed in the duodenum. Clinical improvement was observed after 13 days with extensively hydrolyzed formula and CMP elimination diet. CMP were introduced when the patient had been symptom-free for 11 months. At the time of consent, Patient 4 was 6 years old and doing well.

4 DISCUSSION

The four cases of CMPA presented herein were characterized by severe hypogammaglobulinemia and hypoalbuminemia. Two cases presented with FTT, both with proximal small bowel involvement on biopsy, suggesting that site of inflammation underlies clinical presentation to some extent. These two cases were diagnosed as FPIES. The other two patients came to medical attention at a later age, with no GI symptoms. They were diagnosed as FPE. All cases underwent endoscopy to assess for primary immune deficiency. Immunoglobulin(Ig) G, IgA, and IgM levels normalized on a CMP elimination diet. All four children are well and asymptomatic at follow-up, none having developed symptoms consistent with inflammatory bowel disease (IBD). As median to long-term follow-up of these children has been uneventful and there was no subsequent history of respiratory allergy, the final diagnosis was severe CMPA.

CPMA is a histological diagnostic challenge. These four cases suggest that CPMA with PLE can affect any segment along the GI tract, a feature that has not been clearly reported for two reasons: CPMA is most commonly a clinical diagnosis and (capsule-) endoscopy has been limited to older children. Taken together, this small case series yields a map of histopathologic presentation along the GI tract revealing varying degrees of regional involvement and disease severity.

The histological findings in CMPA vary along the GI tract. Jejunal villous shortening or a pathological villus-to-crypt ratio have been described.2, 6-10 When severe, CMPA may present with diffuse colitis and variable ileal involvement, with ulcers and crypt abscesses; in the distal duodenum and the jejunum, villous atrophy may be seen, together with increased numbers of lymphocytes, plasma cells, eosinophils, and mast cells.11, 12 Endoscopy may show duodenal bulb nodularity13 and biopsy may show lymphonodular hyperplasia in the duodenal bulb and colon.14 These features were not observed in the four patients reported here. Isolated nodular lymphoid hyperplasia has been reported in older patients, without hypoalbuminemia or peripheral eosinophilia.15 CMPA is in the differential diagnosis of very early onset intestinal bowel disease (VEO-IBD). In particular, one of the histological patterns of VEO-IBD, the enterocolitis-like pattern, associates extensive villous atrophy in the small bowel. Although large-bowel mucosal architecture is preserved, edema and mucosal friability may lead to the detachment of the colonic epithelium.16 We observed chronic active duodenitis with partial villous atrophy and regeneration in only one patient, while architecture was preserved in all other patients. This patient, depicted in Figures S1 and S2, showed severe colonic mucosa atrophy with near complete gland loss in the colon and increased apoptotic bodies at time of presentation, something which has been described in congenital immune deficiencie.17 Although immune deficiency should be considered in the face of profound histological alterations, empirically eradicating cow's milk protein from the diet is a practical first step for several reasons: CMPA is a frequent diagnosis, and eradication leads to rapid clinical improvement, serving as diagnostic and management orientation if clinical response is favorable. Of note, despite severe histological findings, endoscopy was normal in this case. Conversely, in another patient featured in Figure 2, capsule video-endoscopy showed active bleeding with linear ulcerations and evidence of villous atrophy, findings that were not confirmed by histology. These two examples highlight the poor concordance between endoscopical and histological findings.

Tissue eosinophilia is expected in a food allergy.18-20 Lamina propria eosinophilia was seen in one or more biopsy locations in all patients; in particular, all three patients with gastric biopsies displayed numerous eosinophils in the gastric lamina propria. Allergic conditions are documented in 58.9% of children with eosinophilic gastritis, and in 51.6% of children with eosinophilic gastroenteritis.21 There are no clear cutoff values for eosinophilic infiltration. Winter et al. reported that finding >60 eosinophils per 10 high power fields (HPF) in the lamina propria was highly specific for allergy-related proctocolitis.22 These numbers were later confirmed by Odze et al.23 In pediatric eosinophilic gastrointestinal disease, clear histological diagnostic criteria are established only for eosinophilic esophagitis, with in particular eosinophil counts defined as ≥15 per HPF. In contrast, the proposed eosinophil thresholds for eosinophilic gastritis (≥30/HPF in ≥5/HPF), eosinophilic gastroenteritis (≥50/HPF in the duodenum), and eosinophilic colitis (>50/HPF in the right colon, >30/HPF in the transverse and left colon) are less-well defined.5, 24 Moreover, to minimize heterogeneity across reports, recent studies recommend standardizing the reporting of eosinophilic infiltration density in cells/mm2.5 Therefore, the current thresholds still require further refinement to ensure consistency. Eosinophils also involved the epithelium, and the muscularis mucosae, in close association with lymphoid aggregates (data not shown). The presence of <6 eosinophils/HPF on average however remains within normal range according to accepted norms.4 Quantifying eosinophils in the lamina propria remains a challenge as numbers may vary with geographic location,5 environmental, dietary, and seasonal causes among others.25 Eosinophils as the main component of crypt abscesses are described in allergic coloproctitis.22 In addition, acute neutrophilic infiltration was observed in two of the four patients presented here, with neutrophilic gland microabscesses in Patient N°2. Again, VEO-IBD should be considered in the differential diagnosis, since eosinophil-rich and mixed enterocolitis-like, eosinophil-rich patterns have been described in this setting.26

Unusual histological features have been reported in CMPA. First, rare examples of giant cell or granulomatous reactions are described in FPIAP;27-29 obviously a differential diagnosis of Crohn's disease, immune deficiency, or infection needs to be considered in such cases. Second, a 7-month-old male presenting with clinical and histological features of abetalipoproteinemia was diagnosed with CMPA.30 The suggestive histological findings consisted of cytoplasmic vacuolization (increased lipid droplets) of duodenal enterocytes, a feature also observed in Patient N°1. Similar findings are, however, also described with fasting and lipid-rich meals.

Finally, all four patients showed some degree of lymphatic duodenal dilatation, albeit mild and focal. PLE has been described in both FPIES and FPE, but the histopathology and the underlying mechanisms remain unclear. PLE can arise owing to different mechanisms: increased lymphatic pressure with lymphangiectasia, mucosal erosion, or a tight junction defect in an otherwise normal appearing mucosa.31 In addition, increased intestinal permeability and fluid shifts secondary to local inflammation, and in particular to eosinophils, have been postulated to contribute to the pathophysiology of PLE in FPIES.11 This concept is not novel as some of these mechanisms have in part been incriminated in IBD where inflammatory mediators interfere with lymphatic vessel function and alter lymph flow, leading to lymphangiogenesis and lymphangiectasia, with increased mucosal edema and inflammation.32, 33 Extrapolating from the IBD literature, we postulate that one of the mechanisms of PLE in CMPA could also be increased lymphatic pressure secondary to mucosal injury and inflammation.

All in all, the cases presented herein suggest that there is no pathognomonic pattern of histological involvement, and that injury may arise anywhere along the GI tract, confirming the findings of others.13, 14 Allergen elimination allows for rapid and complete mucosal restoration in one case and total symptom resolution in all cases, including in severe cases. Finally, tissue eosinophilia is the norm, seemingly unrelated to clinical disease severity.

CPMA, especially non-IgE mediated, remains a diagnostic challenge for several reasons. First, it may present with a wide variety of symptoms ranging from isolated diarrhea/vomiting to FTT or edema. In severe cases, it may resemble congenital enteropathy with or without immune deficiency. Second, it is usually a clinical diagnosis, with no specific laboratory or imaging test. Therefore, although invasive, (capsule-) endoscopy may be a useful diagnostic tool for diagnosis in severe cases, or in cases where etiology is doubtful. PLE is a clinical diagnosis, combining diarrhea and/or edema with hypoalbuminemia. The source of protein loss can be confirmed using A1AT stool clearance after exclusion of renal protein loss.

Second, biological findings associated with CMPA are nonspecific. For example, hypoalbuminemia and thrombocytosis could be due to acute inflammation. Leukocytosis is not the norm, as was not observed in this small series, and only one patient had documented peripheral eosinophilia, also commonly accepted to be suggestive of food allergy in general. Taken together, there is no specific blood marker of PLE due to CMPA. Clinical and biological response to CMP elimination and challenge remains an essential diagnostic tool.

Third, the complex and severe clinical picture may open the same differential diagnosis as the histological patterns to include immune deficiencies and eosinophilic GI disorder. The severity of these four cases could indeed suggest an early IBD or a genetic disease. However, both their short-term and long-term course suggest that empirically removing CMP from the diet, is a pragmatic management method before exploring the possibility of rarer diseases.

While routine endoscopy is not required for the diagnosis of CMPA, (capsule-) endoscopy represents a safe diagnostic procedure in severe cases. It is noteworthy that none of the patients presented herein experienced endoscopy-related complications despite the theoretical infectious risk due to hypogammaglobulinemia and increased intestinal permeability.

5 CONCLUSION

CMPA can present with severe signs and symptoms and affect any segment of the GI tract. The lack of correlation between endoscopy and histological findings highlights the importance of a comprehensive approach to the patient presenting with possible CMPA. Food protein allergy should be sought in infants and children with hypoalbuminemia.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The authors have no funding to report.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST STATEMENT

The authors declare no conflict of interest.