The Three-Way Interaction of Autonomy, Openness to Experience, and Techno-Invasion in Predicting Employee Creativity

ABSTRACT

Despite the increasing need for creativity in rapidly evolving markets and work environments, not all employees are able to engage in this crucial behavior at work. The interactionist perspective suggests that creativity in organizations can be predicted by the interplay of individual and situational elements. With this theoretical framework, the study aimed to generate and develop insights into the job autonomy–employee creativity relationship by proposing and testing the joint moderating role of an individual (i.e., openness to experience) and contextual factor (i.e., techno-invasion). The sample (n = 435) drew from three sources (focal employees, their family members, supervisors) concerning the creativity of working professionals and what predicts it in a variety of industries. The findings reveal a curvilinear relationship between autonomy and creative behavior and the moderating effect of openness to experience in this relationship. Support is also found for the three-way interaction of autonomy, openness to experience, and techno-invasion in fostering creative behavior. Important theoretical and practical implications thus arise for establishing the work context of potentially creative individuals given different levels of technology demands and job conditions.

INTRODUCTION

The high level of creativity required by businesses operating in a global, highly competitive, and dynamic environment is opening new business opportunities (Anderson, Potočnik, & Zhou, 2014; Bledow, Kühnel, Jin, & Kuhl, 2022). Creativity is associated with the realization of original and potentially effective ideas (Shalley, Zhou, & Oldham, 2004). Individuals in a supportive work environment feel they can express their conditions, needs, and feelings and decide how they will do their tasks, which provides a basis for new ideas to emerge (Liu, Jiang, Shalley, Keem, & Zhou, 2016; Oldham & Cummings, 1996). However, the effect of job design on employees' creativity is rarely studied (Zhou, Hirst, & Shipton, 2012). The COVID-19 pandemic had a wide impact on every aspect of life in society. Organizations and businesses were forced to reconsider many operational subjects and strategies in terms of their potential to successfully overcome the challenging circumstances of the pandemic (Austin-Egole & Iheriohanma, 2021).

Broad support can be found for the claim that the generation of novel ideas is likely motivated by individuals' professional experiences and specific aspects of job design (Mumford, Whetzel, & Reiter-Palmon, 1997; Oldham & Cummings, 1996; Zhou et al., 2012). The importance of autonomy is stressed by several scholars (Dul, Ceylan, & Jaspers, 2011; Feist, 1998; Mumford, 2000). Autonomy allows employees to act according to their will to do their work and frees them of firms' limitations, with research showing that employees can be motivated by autonomy and that individuals with a low level of autonomy overall display less creative behavior (Liu et al., 2016; Shalley et al., 2004).

Boundary factors may also play a role, and several scholars have investigated the effects of the interplay of individual and contextual influences on employee creativity (Oldham & Cummings, 1996; Shalley et al., 2004; Zhou et al., 2012). Autonomy helps workers develop greater self-respect, and individuals may thus be free of firms' bureaucratic issues that discourage them from acting creatively (Jaiswal & Dhar, 2017). Creative performance is related to job autonomy, and it is more likely that employees with a stronger creative personality (i.e., natural predisposition for creativity) take advantage of the autonomy in their jobs than individuals who have a lower propensity to be creative (Cai, Song, & Zhao, 2013). Openness to experience is a basic factor of personality that is most often associated with inherently creative individuals (McCrae, 1987, 1993). Individuals with high levels of openness to experience are intellectual, imaginative, sensitive, and open-minded, whereas individuals scoring low for this dimension are insensitive and conventional (Roccas, Sagiv, Schwartz, & Knafo, 2002). Individuals with a higher level of openness to experience tend to follow new experiences and unique processes and things. They are considered as curious and creative, satisfied by exploring and testing new ways (Feist & Feist, 2008; Sahrah et al., 2023). Therefore, granting employees with a high level of openness to experience increased autonomy in their work gives them an opportunity to create more flexible work methods to complete their assignments, where they manage their work by defining their roles and methods in terms of task-related professions (Song, Uhm, & Kim, 2012; Troyer, Mueller, & Osinsky, 2000). However, autonomy does not always suit all employees. Extending the autonomy of individuals with little experience and a low level of openness to experience (as the main factor of creative personality) may lead to stress and confusion (Caniëls, de Jong, & Sibbel, 2021; Johns, 2010) and reduce their creativity (Chua & Iyengar, 2006). Some employees might also prioritize their own goals and priorities (Baumann & Kuhl, 2002), which may be out of step with the organization's perspective or objectives. Several studies reveal that creative behavior is more likely to be evidenced among employees whose openness to experience is on a higher level (Feist & Feist, 2008; Sahrah et al., 2023), making this individual difference a potentially important boundary condition in the autonomy–creativity relationship.

Technology also has a tremendous impact on lives and work today, mostly making them easier. Nevertheless, technology also comes with a few negative effects, such as technostress, which has risen in recent years. Technostress is an individual's experience of finding it difficult to adapt to modern technologies. Employees often exhibit different behavioral patterns in response (Dehkordi & Khani, 2021). Such stress has been described using a multidimensional structure containing five dimensions: techno-overload, techno-invasion, techno-complexity, techno-insecurity, and techno-uncertainty (Tarafdar, Tu, Ragu-Nathan, & Ragu-Nathan, 2007). Technology obliges individuals to work more and faster, which can lead to techno-overload. Another effect is that it makes individuals reachable at all hours, namely, they feel constantly exposed, which can trigger a sense of techno-invasion. Techno-complexity, that is, complexity of computer software and systems, forces individuals to learn continuously. Employees might also fear losing their jobs to people holding greater expertise in technology, thereby feeling techno-insecurity, while the short lifecycle of computers means their knowledge is outdated rapidly, which encourages a feeling of techno-uncertainty (Chandra, Shirish, & Srivastava, 2019). Techno-invasion denotes individuals “always being on” since they are accessible at all times, which makes them feel it is essential that there be no interruptions in their connectivity (Chandra et al., 2019). This phenomenon has emerged from the near-universal use of information and communication technology (ICT) in recent times by most of the population (La Torre, Esposito, Sciarra, & Chiappetta, 2019).

The COVID-19 pandemic forced alterations in work habits and increased individuals' dependence on ICT, with many employees suddenly needing to work from home. Since this change was neither voluntary nor planned, continued for a long time, and included whole families that ended up house-bound together, it seems that employees experienced both longer work hours (DeFilippis, Impink, Singell, Polzer, & Sadun, 2020) and a worse work–life balance (Austin-Egole & Iheriohanma, 2021). The pandemic and working from home have seen “techno-invasion” become more prominent than other stressors. Techno-invasion constantly interferes with employees' need for privacy and flexibility. It is possible that employees initially accept and even demand a low level of techno-invasion because that helps them have time and resources to communicate with each other, which contributes to their creativity and innovation (Chandra et al., 2019). Limiting the invasion of technology can assist individuals with better connectivity and control over their job and task. Accordingly, a low level of techno-invasion may be beneficial for employees' creative behavior. Autonomy, likewise, provides employees with the freedom to decide how to complete their tasks (Liu et al., 2016). Employees with a higher level of openness to experience can benefit from these options in particular as they may be more inclined to use the technological connectivity tools and their autonomy engage in higher creative behavior (Sahrah et al., 2023). Techno-invasion may thus be a crucial factor in predicting employee creativity in the interplay of autonomy and openness to experience.

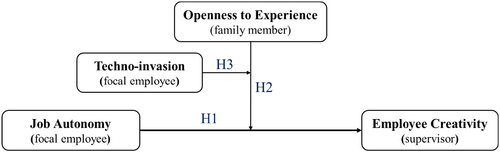

Therefore, building on the interactionist perspective on creativity (Woodman, Sawyer, & Griffin, 1993), which considers both individual and situational factors to determine how creativity in an organization occurs when they simultaneously influence and interact with each other (Mischel, 2004; Shoda, Cervone, & Downey, 2007), we aim to explore the relationship among autonomy, techno-invasion, openness to experience, and employee creativity by applying a three-source (employees, supervisors, family members) research design. Experts state that employees' belief in the organization's purposes and their autonomy in completing their tasks may be vital for ensuring that they enjoy contributing with their creativity (Dhar, 2012). Creative individuals in an autonomous environment often feel compelled to utilize their talents to exhibit creativity (Ramamoorthy, Flood, Slattery, & Sardessai, 2005). In other words, job autonomy can act to energize employees and be a source of inspiration for their creativity (Jaiswal & Dhar, 2017). On the other hand, the review of Puryear, Kettler, and Rinn (2017) showed that commonly accepted beliefs about a creative personality (like being typically open to experience and extraversion) were generally supported as predicting creativity. With this main premise, this paper intends to make two contributions to the literature on creativity.

First, this research aims to shed more light on the interplay of job design and openness to experience in predicting creativity. The study specifically focuses on autonomy and creativity, advancing this stream of research by indicating that openness to experience plays a vital boundary role which changes the nature of the relationship and enables the intended outcome of autonomous job design: the highest levels of creativity.

Second, the paper attempts to bridge the technology–creativity literatures by introducing techno-invasion as another boundary contingency in the mentioned relationships. Nonetheless, it is possible that workers become more effective in their day-to-day tasks while the stress arising from technology increases, with this negatively affecting their creative behavior up to a certain level of techno-invasion and thereafter may have a positive effect on their creative behavior (Chandra et al., 2019). Hence, individuals dealing with a certain level of techno-invasion for a longer period gain the ability to cope with it and be more flexible. This flexibility may boost their creative thinking and lead to higher creative behavior (Chandra et al., 2019).

THEORETICAL BACKGROUND AND HYPOTHESES DEVELOPMENT

Creativity, which means the generation of novel and useful ideas, is likely an outcome of the interconnection of an employee's motivation and related skills (Amabile, 1983). It is believed that dealing with complicated and challenging tasks and possibly also experiencing welfare, curiosity, happiness, or favorable challenges, makes employees creative (Amabile, 1996). The context of a given task namely has an important effect on employees' tendency to display creative behavior in their work (Ford, 2000).

The interactionist perspective on creativity places emphasis on the effect of situational factors on employees' creativity, which is the basic source of innovation (Amabile, 1997). However, this perspective proposes that to ensure a better understanding of creativity one must acknowledge employees' individual characteristics as well (Amabile, 1996; Woodman et al., 1993). This means that separating individual and situational factors and their particular impacts on creativity is insufficient (Bledow et al., 2022). The interactions between these two factors should in fact be examined and the responses of people to different situations taken into account (van Knippenberg & Hirst, 2020; Zhou & Hoever, 2014).

The research presented in this article is thus based on the interactionist perspective that explains how creativity occurs in organizations following the interactions of individual and environmental elements (Shalley et al., 2004; Tett & Burnett, 2003). Autonomy has been considered a vital factor for stimulating creativity (Amabile, 1988, 1996; Černe, Hernaus, Dysvik, & Škerlavaj, 2017). Job autonomy is a key aspect of job design that predicts individuals' motivation and thereby fosters employees' creativity (Amabile & Pratt, 2016; Gagné & Deci, 2005) where employees' motivation is essential for creative actions (Ilha Villanova & Pina e Cunha, 2021).

AUTONOMY AND CREATIVITY

High-quality job design is a method for creating high-quality jobs that enable employees to become more flexible and give them power to make decisions concerning their main tasks (Arthur, 1994; Walton, 1985; Wood & de Menezes, 2008). Greater autonomy gives employees more opportunities to display their creativity via the experience of having flexibility in their work process, and while assigning task-related jobs to them they can determine their responsibilities and their roles to complete their given tasks (Song et al., 2012; Troyer et al., 2000). Job autonomy, indicating a low job structure, that is, a loosely defined job, is accordingly critical for processing and operating innovations (Song et al., 2012; Wang & Cheng, 2010). While the bureaucratic processes in an organization often prevent workers from performing creatively, autonomy frees them to develop self-esteem and act creatively (Jaiswal & Dhar, 2017).

In contrast, a high level of autonomy and having to choose from among numerous options can lead to stress and insecurity (Caniëls et al., 2021), which negatively impact employees' physical and mental health (Schwartz, 2004) and reduce their creativity (Chua & Iyengar, 2006). A job design featuring high autonomy and a low structure may produce unwanted consequences like mental and emotional tiredness (Johns, 2010). On the other hand, according to the Too-Much-of-a-Good-Thing Effect principle, too much autonomy may lead to a decline in employees' creativity (Pierce & Aguinis, 2013). Nevertheless, providing employees with autonomy and the right to choose is not a simple task, and empowering employees in this way does not always bring a positive outcome (Locke & Schweiger, 1979) as it hinges on multiple factors (Chua & Iyengar, 2006). Therefore, a high level of autonomy does not always suit every employee. Thus, we assume that a higher level of autonomy can benefit employee creativity up to the point where there is still some kind of structure and monitoring in place. If employees are given too much autonomy, their creativity will drop due to possible confusion. However, when full autonomy is given, confusion may ensue that then disrupts the trajectory of creativity, ultimately leading to a decline (Chua & Iyengar, 2006). The following is therefore posited:

H1.An inverse-U-shaped curvilinear relationship exists between autonomy and employee creativity.

THE MODERATING EFFECT OF OPENNESS TO EXPERIENCE: A TWO-WAY INTERACTION

Employees' personal characteristics like their relevant knowledge, cognitive style, and personality directly affect their creative performance (Amabile, 1996). Moreover, firms are typically staffed by individuals with different characteristics and high or low levels of personal creativity (Cai et al., 2013). Research shows that employees whose creative personality is on a higher level tend to have more creative behavior in their tasks than others (Feist & Feist, 2008; Sahrah et al., 2023). Openness to experience (as a key feature of a creative personality) and autonomy assist workers to have a clear vision of their tasks and motivate them to develop a critical viewpoint for solving problems. Jobs with high autonomy are more likely to assist individuals possessing considerable creativity to expand their creative behavior (Cai et al., 2013).

Boundary factors could play a role, and several scholars have investigated the interplay of individual and contextual impressions on individual creative behavior (Oldham & Cummings, 1996; Shalley et al., 2004; Zhou et al., 2012). Individuals with a high level of openness to experience would be more motivated by either internal or external factors. On the other hand, job autonomy as an external element acts to further motivate employees with considerable openness to experience to engage in creativity (Jaiswal & Dhar, 2017). A low level of autonomy in jobs means the presence of rigid structures and monitoring. Therefore, there are boundaries for individuals' activity and creativity. However, it means that individuals are aware of the limitations, and since there is no confusion for them when they have a high level of openness to experience, they are expected to show a relatively higher level of creativity. While, at the medium level of autonomy, when they are able to make some of their decisions freely, and still there is structure and monitoring, individuals with a high level of openness to experience, who are naturally curious about interpreting social and contextual cues, may experience confusion suffer from unclear situations, and show less creative behavior.

The freedom and independence flowing from a high level of autonomy give individuals with a high level of creativity an opportunity to utilize their capability and exhibit a higher level of creativity (Dhar, 2012). Yet, it is possible that employees with a low level of openness to experience who do not experience any autonomy in their jobs may not feel the need to behave creatively in their jobs, which leads to fewer incidents of creative behavior (Chua & Iyengar, 2006). Meanwhile, a medium level of autonomy may assist them to increase their creative behavior. On the other hand, these employees may develop tension and self-doubt in response to being given a high level of autonomy (Caniëls et al., 2021). Thus:

H2.Openness to experience moderates the curvilinear relationship between autonomy and employee creativity; for high levels of openness to experience, the relationship is curvilinear U-shaped, whereas for low levels of openness to experience, the relationship is curvilinear, inverse-U-shaped.

TECHNO-INVASION AS A CONTINGENCY IN THE AUTONOMY–OPENNESS TO EXPERIENCE–CREATIVITY INTERPLAY

Brod (1984) was the first to define technostress, describing it as an illness caused by an inability to adapt to new technologies, especially the computer, which leads to either over-identification or computer anxiety. In 2008, Ragu-Nathan and colleagues claimed that technostress is when someone is under pressure due to problems and difficulties of overcoming and becoming familiar with ICT. Subsequent studies have shown that techno-invasion, as one of the main technostress measurement variables, can have different outcomes for innovation and creative performance (Byron, Khazanchi, & Nazarian, 2010; Chandra et al., 2019; La Torre et al., 2019; Ragu-Nathan, Tarafdar, Ragu-Nathan, & Tu, 2008; Tarafdar, Tu, & Ragu-Nathan, 2010) and that individuals can have a sense of progress in their tasks instead of setbacks (Chandra et al., 2019). Moreover, techno-invasion as a stressor has varying effects at different levels of job autonomy, which means high levels of autonomy are generally associated with low levels of stress (Brooks & Califf, 2017). Since the relationship between performance and techno-invasion has normally been studied as a linear relationship, it is reasonable that in earlier studies techno-invasion usually had a negative effect on outcome variables like performance, creativity, or innovation (Leung, Huang, Su, & Lu, 2011).

Further, research reveals both a negative and a positive relationship between stress and job outcomes (Srivastava, Chandra, & Shirish, 2015). This means that the relationship of techno-invasion with creativity varies according to the levels of individuals' openness to experience and their job autonomy, where individuals with greater flexibility in their work experience more confusion while performing their tasks, and hence have a higher level of stress (Caniëls et al., 2021). Yet, more job feedback and a lower level of job autonomy are generally associated with less stress (Ragu-Nathan et al., 2008). In what follows, we present and conceptualize scenarios related to levels of openness to experience and techno-invasion in moderating the curvilinear relationship between autonomy and creativity.

High openness to experience and high techno-invasion

Employees with high levels of openness to experience who benefit from a high level of job autonomy are more likely to view techno-invasion negatively because it influences their creativity and divergent thinking (Bala & Venkatesh, 2013). Therefore, when the techno-invasion is high, a lower level of creative behavior is expected (Leung et al., 2011) due to individuals having less time and energy to devote to creativity, and the lack of the inherent drive of their openness to experience to exhibit creative behavior. The response to a high level of autonomy can change due to high levels of techno-invasion of individuals with a high level of openness to experience. Accordingly, these individuals demonstrate lower levels of creative behavior when they face a high level of autonomy and techno-invasion.

High openness to experience and low techno-invasion

It is expected that techno-invasion generally decreases individual creative behavior (Leung et al., 2011), whereas a low level of techno-invasion can provide individual connection and control over their job and task (Chandra et al., 2019), which may positively affect the relationship between autonomy and creative behavior for individuals with a high level of openness to experience. When techno-invasion is low, we expect a U-shaped relationship between autonomy and creative behavior for individuals possessing a high level of openness to experience. Namely, a higher level of creative behavior is expected when individuals with a high level of openness to experience benefit from a low level of autonomy. While these individuals sense confusion due to a medium level of autonomy and some control and monitoring, a high level of creative behavior is, however, expected when they possess a high level of autonomy (Dhar, 2012).

Low openness to experience and high techno-invasion

When individuals have a low level of openness to experience, they are expected to exhibit a lower level of creativity in different circumstances. Generally, techno-invasion negatively affects the creative behavior of individuals (Leung et al., 2011), and a higher level of autonomy can provide individuals with opportunities to demonstrate a higher level of creative behavior (Dhar, 2012). Still, a high level of autonomy may cause confusion among individuals with a lower level of openness to experience (Caniëls et al., 2021). Individuals with a low level of openness to experience who are exposed to a high level of techno-invasion may show a higher level of creativity when they have a low level of autonomy. However, these employees are expected to show a lower level of creativity in jobs with a medium level of autonomy with some structures and monitoring. While they expected to have a higher level of creative behavior due to a high level of autonomy (Dhar, 2012), this means that a U-shaped relationship between autonomy and creative behavior is expected when the techno-invasion is high for individuals possessing a low level of openness to experience.

Low openness to experience and low techno-invasion

A low level of techno-invasion may contribute to individuals' creativity and innovation (Chandra et al., 2019), whereas autonomy allows them to decide how to complete their tasks and to be creative. For individuals with a low level of openness to experience, lower creative behavior is expected when autonomy is lower, and jobs are accompanied by rigid structures. As autonomy grows, a small increase in creative behavior is expected. In contrast, a high level of autonomy may cause confusion for individuals with a low level of openness to experience. The relationship between autonomy and creative behavior for individuals with a low level of openness to experience who are exposed to a low level of techno-invasion is therefore expected to be inverse-U-shaped.

H3.There is a three-way interaction effect among autonomy, openness to experience, and techno-invasion in predicting employee creativity. Highest levels of creativity occur when employees possess high levels of autonomy, a high level of openness to experience, and a low level of techno-invasion.

Figure 1 presents the conceptualized research model with hypotheses.

METHODOLOGY

SAMPLE AND COLLECTION OF DATA

Data were collected in March 2021 in Montenegro in various industries and workplaces using a nonprobability convenience purposive sampling strategy targeting matched triads of employees, their family members, and the employees' supervisors. Different industries were studied to ensure a mix of work situations for variables in an organizational context and the population's status in the case of COVID-19 measures and their influence while performing the research. To assure highly pervasive and wide outcomes and reduce the challenges, 517 employees were studied. The sample was drawn from different industries and situations, including managers, finance agents, computer agents, and the IT section through to production and manufacturing. Finally, 435 complete responses (consisting of the mentioned matched triads) were obtained and used to test the hypotheses. The majority of employees studied were born between 1954 and 2001 (age mean = 36.31; SD = 10.85); 40.7% of the population was female and 59.3% was male.

MEASURES

All variables were measured using a 5-point Likert scale (1 = totally disagree, 5 = totally agree).

Autonomy as an independent variable was self-assessed as measured by the Work Design Questionnaire (WDQ) (Morgeson & Humphrey, 2006) with three items (Cronbach's α = .76). A sample item is: “The job allows me to make my own decisions about how to schedule my work.” Employee Creativity was treated as a dependent variable assessed from the perspective of supervisors with 10 items focused on idea-generation (not implementation) from the (Zhou & George, 2001) scale (Cronbach's α = .89). A sample item is: “How often does this employee … generate original solutions to problems?”

Openness to experience as a way to capture creative personality represents the first moderator variable. This was measured by two items taken from the openness to experience dimension of creative personality, similar to the studies of (Aleksić, Černe, Dysvik, & Škerlavaj, 2016; Dollinger, Urban, & James, 2004) on the Big 5 personality scale (John & Srivastava, 1999) (Cronbach's α = .63). The variable was assessed from the perspective of family members, as significant others or individuals close to focal employees might be well suited (perhaps better than supervisors or colleagues) to recognize their specific personality patterns due to strong familial bonds and frequent off-work interaction as well. A sample item is: “I see this person as someone who … is original, comes up with new ideas.” The other moderator Techno-invasion was self-assessed by four items from the technostress scale developed by Shu, Tu, and Wang (2011), self-rated from the perspective of employees (Cronbach's α = .70). A sample item is: “I have a feeling that I cannot detach from my work due to technology.”

Alongside the study's focal variables, whether respondents (based on their self-reports) mainly worked remotely was controlled with a dummy variable (1 = remote, 0 = on-site work). Controlling whether an individual is working on-site or remotely is important because previous studies (e.g., Hurbean, Dospinescu, Munteanu, & Danaiata, 2022) suggest that remote workers tend to work more and longer hours due to the use of ICT, yet do not perceive the techno-invasion as strongly as employees who work on-site. The use of ICT brings to them a sense of connectedness and involvement. Employees enjoying greater control over their work environment and schedule (i.e., remote workers) are thought to have perceptions of greater control and less stress related to work–family conflict (i.e., techno-invasion impact) than workers who work on-site. Taken together, the three-source research design helps alleviate the common method bias concerns that frequently appear in research (Conway & Lance, 2010).

ANALYTIC PROCEDURE

In the first step, using AMOS software the overall measurement model was tested with regard to how it matches the data by conducting confirmatory factor analysis (Arbuckle, 1997). After confirming the model and selecting the variables, descriptive statistics were determined. Regression-based analyses were used to test the hypotheses; quadratic regression analysis to test Hypothesis 1, and then Model 1 and Model 3 in PROCESS macro version 3 (Hayes, 2018, 2021) to test Hypotheses 2 and 3, respectively.

RESULTS

DESCRIPTIVE STATISTICS AND RELIABILITY

Descriptive statistics, correlations, and reliability coefficients for the variables in this study are shown in Table 1. A positive correlation is apparent between autonomy and creative behavior (r = .20, p < .01), the same with the relationship between openness to experience and creative behavior (r = .23, p < .01). Although the correlation between techno-invasion and creative behavior is not negative, it is not significant. According to the reliability coefficients, all of the scales may be considered to be internally consistent. All Cronbach's α of the variables exceed the .70 criterion (Hair, Ortinau, & Harrison, 2010) and are thus acceptable. The CFA results showed a good model fit (CFI = .926, RMSEA = .059, chi-square = 326.266, df = 129, p < .000).

| Variable | n | M | SD | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Techno-invasion | 203 | 2.56 | .82 | (.70) | |||

| 2. Autonomy | 203 | 3.63 | .82 | .02 | (.76) | ||

| 3. Openness to experience | 203 | 3.75 | .82 | .06 | .15** | (.63) | |

| 4. Creativity | 203 | 3.81 | .64 | .02 | .20** | .23** | (.89) |

- Note. Cronbach's alpha on the diagonal in parentheses.

- ** p < .01.

RESULTS OF REGRESSION ANALYSIS

Autonomy–creativity

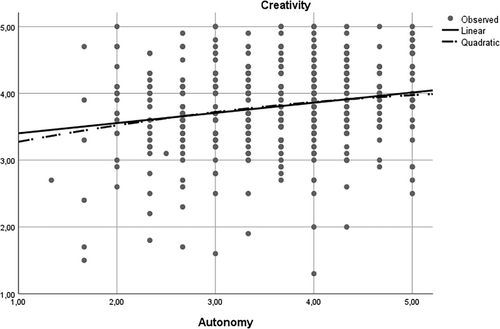

The results presented in Table 2 show a positive relationship between autonomy and creative behavior. Even though both the linear relationship (R-square = .038, F = 17.081) and inverse-U-shaped curvilinear relationship (R-square = .039, F = 8.884) are significant, the quadratic relationship due to the slightly bigger R-square indicates a bigger proportion of variance explained by the quadratic model; see Figure 2. The first hypothesis concerning the existence of a curvilinear relationship between job autonomy and creative behavior is thereby supported.

| Equation | Model summary | Parameter estimates | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| R-Square | F | df1 | df2 | Sig. | Constant | b1 | b2 | |

| Linear | .038 | 17.081 | 1 | 434 | .000 | 3.252 | .152 | |

| Quadratic | .039 | 8.884 | 2 | 433 | .000 | 2.884 | .378 | −.033 |

- Note. Dependent Variable: Creativity, Independent variable: Autonomy.

Openness to experience as a moderator of the curvilinear inverse-U-shaped relationship between autonomy and creative behavior

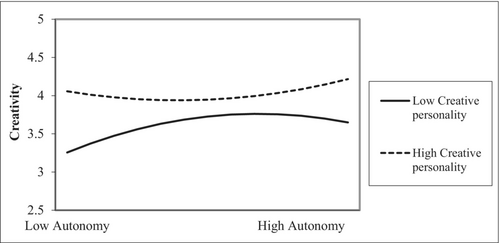

The results of testing model 1 are provided in Table 3 and explain the effect of the interaction of openness to experience and job autonomy on creative behavior. The interaction between autonomy and openness to experience (p < .05) is significant, thus giving support for H2 concerning the moderating effect of openness to experience on the relationship between job autonomy and creative behavior. For a high level of openness to experience (β = −.0967, p = .0312), the relationship of autonomy with creative behavior will be inverse-U-shaped curvilinear, while for an individual whose openness to experience is on a low level (β = .0528, p = .03195) the relationship will be U-shaped curvilinear.

| Effect | Estimate values | Standard error | 95% Confidence interval | p | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Lower limit | Upper limit | ||||

| Fixed effects | |||||

| Intercept | 3.429 | .254 | 2.928 | 3.929 | .000 |

| Openness to experience | 0.102 | .066 | −0.027 | 0.232 | .121 |

| Autonomy Squared | −0.494 | .188 | −0.086 | −0.124 | .009 |

| Autonomy Squared × Openness to experience | 0.122 | .049 | 0.025 | 0.220 | .013 |

| Autonomy | 0.085 | .039 | 0.007 | 0.164 | .032 |

This means that employees with a high level of openness to experience and a low level of job autonomy demonstrate relatively more creative behavior, while when their job autonomy rises their creative behavior shrinks, when they have a medium level of autonomy their creative behavior increases, and they demonstrate the highest level of creative behavior when they possess the highest level of autonomy. In comparison, individuals who are less open to experience show a lower level of creative behavior when they benefit from a lower level of autonomy, while with the medium level of autonomy when they still need to follow some structures, they show the highest level of creativity after which point their creative behavior starts to decline again. However, with any level of autonomy, those with a higher level of openness to experience have a higher level of creative behavior. The conditional effects of job autonomy on creative behavior at different moderating variable values are shown in Table 4. Figure 3 adds clarity by presenting a visual diagram of these relationships to permit better understanding of these interactive effects.

| Effect | Estimate | Standard error | p | Conclusion |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Openness to experience | ||||

| Low | −0.096 | .044 | .031 | Significant |

| Average | −0.022 | .038 | .569 | Non-significant |

| High | 0.052 | .053 | .031 | Significant |

The three-way interaction of autonomy, openness to experience, and techno-invasion

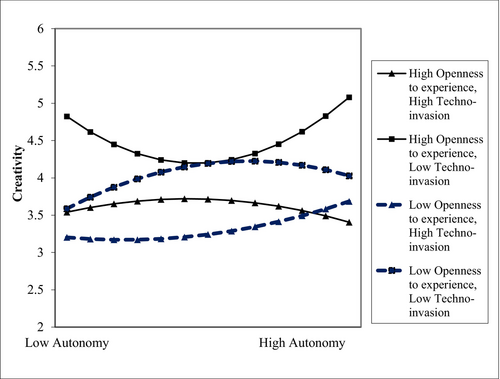

The results of the three-way interaction of autonomy, openness to experience, and techno-invasion on creative behavior are presented in Table 5 where the interaction among these three variables and creative behavior is supported. For high openness to experience and low tech-invasion (β = .1564, p = .0210), the job autonomy–creative behavior relationship is U-shaped, the same as when openness to experience is low and tech-invasion is high (β = −.0542, p = .4179). On the other hand, for high openness to experience in the presence of high tech-invasion (β = −.0809, p = .2947), this relationship is inverse-U-shaped, the same as with a low level of openness to experience and a low level of tech-invasion (β = −.1432, p = .0093); see Table 6. To facilitate better understanding, these plots are displayed in Figure 4.

| Effect | Estimate values | Standard error | 95% Confidence interval | p | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Lower limit | Upper limit | ||||

| Fixed effects | |||||

| Intercept | 4.354 | .841 | 2.699 | 6.009 | .000 |

| Openness to experience | −0.157 | .215 | −0.580 | 0.265 | .465 |

| Autonomy Squared | −1.959 | .543 | −3.027 | −0.892 | .000 |

| Autonomy Squared × Openness to experience | 0.531 | .143 | 0.248 | 0.814 | .000 |

| Techno-invasion | −0.359 | .325 | −0.999 | 0.279 | .269 |

| Autonomy Squared × Techno-invasion | 0.585 | .205 | 0.181 | 0.989 | .004 |

| Openness to experience × Techno-invasion | 0.102 | .082 | −0.058 | 0.263 | .212 |

| Autonomy Squared × Openness to experience × Techno-invasion | −0.163 | .054 | −0.270 | −0.057 | .002 |

| Autonomy | 0.082 | .039 | 0.004 | 0.161 | .038 |

| Remote work | −0.141 | .097 | −0.332 | 0.049 | .146 |

| Moderators | Estimate | Standard error | p | Conclusion | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Techno-invasion | Openness to experience | ||||

| Low | Low | −0.143 | .054 | .009 | Significant |

| Low | Average | 0.006 | .047 | .889 | Non-significant |

| Low | High | 0.156 | .067 | .021 | Significant |

| Average | Low | −0.098 | .045 | .030 | Significant |

| Average | Average | −0.030 | .039 | .442 | Non-significant |

| Average | High | 0.037 | .053 | .483 | Non-significant |

| High | Low | −0.054 | .066 | .417 | Non-significant |

| High | Average | −0.067 | .058 | .249 | Non-significant |

| High | High | −0.080 | .077 | .294 | Non-significant |

We also controlled for whether employees worked on-site or remotely since previous research (e.g., Hurbean et al., 2022) showed that techno stressors have different effects on these two groups of employees based on their work location. Yet, in our case, this control did not yield a significant relationship with creativity.

DISCUSSION AND CONCLUSIONS

In this article, a curvilinear and interactionist approach was adopted to examine the relationship of job autonomy with employees' creative behavior and the moderating effect of openness to experience and techno-invasion. In support of the first hypothesis, both linear and curvilinear relationships were significant, while a slightly larger R-square of the quadratic relationship explained a higher proportion of variance. The creative behavior of employees with both a low level and a very high level of autonomy is low, whereas a condition of medium level of autonomy reveals the highest levels of creative behavior. The fact that a high level of autonomy leads to diminished creativity behavior is emphasized. The results also reveal that employees with different levels of openness to experience demonstrate different levels of creative behavior when given the same level of autonomy, meaning that openness to experience moderates the relationship of autonomy with creative behavior.

The outcomes of the analysis show that when high openness to experience is involved, the relationship changes to become curvilinear U-shaped. Namely, employees with a higher level of openness to experience display a relatively higher level of creative behavior when faced with a low level of autonomy; on the other hand, when autonomy reaches a medium level, their creativity declines to the lowest level. Meanwhile, they tend to have the highest level of creativity when they are given higher job autonomy. Still, this relationship is reversed for individuals with a low level of creative behavior. This means they have the lowest level of creativity when they possess little autonomy and on a medium level of autonomy, they display the highest level of creative behavior. Nevertheless, after this point, their creative behavior tends to decline and hence this relationship is inverse-U-shaped for employees whose openness to experience is on a low level.

The presented research is in harmony with the notion that individuals must be provided with time and resources to tackle the growing stress of techno-invasion to assure that they can produce outcomes based on creativity, such as innovation (Galluch, Grover, & Thatcher, 2015). Organizations should be careful not to dose too much techno-invasion to ensure the best outcomes of the autonomous job design of creative employees in terms of their creative work behavior. The results for the three-way interaction of autonomy, openness to experience, and techno-invasion on creative behavior mean that this interaction is supported. These findings show that techno-invasion has a negative effect on the creative behavior of employees with either a high or low level of openness to experience. The autonomy–creative behavior relationship is U-shaped for individuals whose openness to experience is on a low level and face high techno-invasion. They namely have a higher level of creativity when their autonomy is on its lowest level, and their creative behavior decreases when increasing the autonomy up to the medium level, and they show their highest creative behavior when granted the highest level of autonomy. This relationship is the same for individuals with a high level of openness to experience coupled with low techno-invasion, which means they have a relatively high level of creative behavior when there is no autonomy and the lowest level of creative behavior at the medium level of autonomy while, by increasing the autonomy to the highest level, they tend to reveal the highest level of their creative behavior.

Moreover, the autonomy–creative behavior relationship is inverse-U-shaped when both openness to experience and techno-invasion are either low or high. In other words, both individuals with a high level of openness to experience and a high level of techno-invasion or with a low level of openness to experience and a low level of techno-invasion have a low level of creative behavior when they have little autonomy and by increasing their job autonomy their creative behavior increases too, while beyond a medium level of autonomy their creative behavior starts to decline. Support was found for the notion that employees with high openness to experience, low techno-invasion, and a high level of autonomy in their jobs display the highest levels of creativity.

THEORETICAL CONTRIBUTIONS

Amabile (1996) stated that creativity contains employees' creativity-relevant skills and knowledge, and work-related factors, such as job autonomy and stress, as well as personal characteristics. However, empirical studies on creativity in the context of digitalization remain limited. The interactionist perspective contends that it is essential to consider both personal and organizational elements seeking to predict creativity in firms (Mischel, 2004; Shoda et al., 2007). In the research presented in this article, openness to experience was studied as a personal factor (Amabile, 1996; Woodman et al., 1993) along with job autonomy (Amabile & Pratt, 2016; Gagné & Deci, 2005) and techno-invasion (Galluch et al., 2015) as work-related factors that affect creativity.

The research makes two main contributions to the fields of job design, creative behavior, and the interactive relationship between organizational and individual factors. First, we advanced the creativity literature by studying the impact of job autonomy on employees' creative behavior as moderated by the effect of openness to experience. Employees with a high level of autonomy are more motivated to show their creative behavior (Dhar, 2012); autonomy also helps employees become free of bureaucratic hurdles (Jaiswal & Dhar, 2017) and allows employees to be more flexible in their decisions concerning how to complete a given task (Wood & de Menezes, 2008), which lets them act more flexibly and be more creative.

The findings show that autonomy has different effects on the individual's creative behavior according to the level of their openness to experience. When a low level of openness to experience is involved, employees with a medium level of autonomy display the highest levels of creative behavior. Conversely, the highest levels of creative behavior among individuals with high openness to experience occur when they are granted the highest level of autonomy. This importantly means that a high level of autonomy for employees generally will not bring about higher levels of creativity. It should also be stressed that a job without flexibility and autonomy will not allow employees to act creatively.

Second, the study extends the interactionist perspective on creativity (Woodman et al., 1993) by examining the effects of the interaction of job autonomy, openness to experience, and techno-invasion on creative behavior. Previous studies showed that stress can have both positive and negative effects on job outcomes (Srivastava et al., 2015). By considering the curvilinear relationship between the variables, the presented findings explain that at various levels of job autonomy and openness to experience techno-invasion can have a different curvilinear influence on employees' creative behavior.

The relationship between autonomy and creative behavior for individuals with a high level of openness to experience who face a low level of techno-invasion is U-shaped and curvilinear, which means that when given a high level of autonomy they engage in the highest levels of creativity. Still, when there are high levels of techno-invasion and openness to experience, the autonomy–creativity relationship will be inverse-U-shaped curvilinear and, thus, by increasing their autonomy the creativity of the employees will drop. On the other hand, in a situation when openness to experience is on a low level and techno-invasion is high, autonomy has a U-shaped relationship with creative behavior, while with a low level of techno-invasion this relationship is inverse-U-shaped.

Finally, empirically speaking, the three-source research design with data on respective constructs collected from the perspective of focal employees, their family members, and supervisors represents an important element of methodological rigor underlying implementation of the presented research model. In creativity research, as in many other fields, inflation of the obtained strengths of relationships sometimes occurs owing to common method variance in research using self-ratings of creativity (Ng & Feldman, 2012), although other ratings are increasingly becoming the norm for creativity assessments. Our supervisory ratings of creative output, as well as family members' ratings of openness to experience, address concerns related to common method variance challenges.

PRACTICAL IMPLICATIONS

The study offers a few management practices that can provide potential positive effects on employees' creative behavior. Managers must carefully investigate the different personality traits influencing the perception of techno-invasion and the measures to reduce the negative interaction with the openness to experience of the employees. Therefore, the measures should consider introducing a combination of tactics considering the broader organizational context and individuals' characteristics.

Techno-invasion acts as an important job constraint for employees with high openness to experience because it decreases the resources available to engage in creative thinking (Jaiswal & Dhar, 2017). Therefore, managers and organizations should engage in preventive solutions for high levels of techno-invasion of employees with high openness to experience. Thus, managers should monitor indications of the high techno-invasion of employees who possess high openness to experience and allow them considerable job autonomy to ensure the employees' highest creative behavior by using adaptive coping strategies. Nevertheless, a high techno-invasion might be positive for employees with low openness to experience when coupled with a medium level of job autonomy. This means good understanding of the interaction of technology with individual and contextual factors impacting creativity might result in the more effective employment of technology and the mitigation of harm. Managers should also provide additional resources for learning and technology use to support the detrimental techno-invasion effects on psychological and physical health, providing for a healthy workplace with established work–life balance. Potential remedies could be introducing comprehensive communication measures; investing in intuitive, user-friendly IT solutions, limiting external stimuli, and setting timeframe boundaries to keep work–life balance. In addition, avoiding the dysfunctional interaction of techno-invasion with employees' need for autonomy and creativity could prevent them from developing turnover intentions fostered potentially by stress, depression, and anxiety (Allen & Page, 2005; Reinecke et al., 2017).

LIMITATIONS WITH FUTURE RESEARCH DIRECTIONS

Our study has several limitations that refer to future research avenues. The data collection occurred during the COVID-19 pandemic and in a single country (Montenegro). Similar research should be performed in a more “normal,” non-pandemic situation. The study also does not allow for conclusions about causality due to its cross-sectional design. We applied a three-source research design whereby, for example, direct supervisors assessed employees' creativity (generally recognized as a strength in creativity research, cf. Ng & Feldman, 2012). While clearly a strength, it came with trade-offs requiring us to apply shortened scales in certain instances (e.g., for openness to experience) to not overburden respondents and reduce the sample size (which was already challenged by the fact that fully completed questionnaires from triads were needed). We suggest that future research address these concerns and use full scales to capture the constructs in our research model. In our research design, family members assessed focal employees' creative personality in terms of openness to experience. Future research could focus on assessing creative personality with other variables like preference for creativity or creative thinking styles, and apply a self-report approach to detecting this phenomenon.

Yet, since R&D team members are highly focused on creativity, a sample of R&D team members could be used to provide more details regarding the contextual focus of a study. Future studies should explore other models that influence employee creativity in either R&D teams or other knowledge-based teams in firms. Further, apart from examining the factors affecting employee creativity, it is equally important to investigate the outcome of employee creativity in various industries.

CONCLUSION

When employees are granted high levels of autonomy, this is generally good for their creativity; however, excessive autonomy brings diminishing returns. Our study on the curvilinear relationship between autonomy and creativity and its boundary conditions contributes theoretical and practical insights in this area since it is the first to investigate the curvilinear interaction among autonomy, openness to experience, and techno-invasion on employees' creative behavior. Our findings provide valuable insights into the complex relationship between autonomy, openness to experience, and techno-invasion in shaping employees' creative behavior. The results indicate that individuals possessing a higher level of openness to experience benefit more from job autonomy and a low level of techno-invasion. We also observed that a high level of techno-invasion has a negative effect on employees' creative behavior. The findings suggest that a different approach is needed to comprehend how different factors impact individual creative behavior in the workplace. Such findings are capable of assisting organizations seeking to boost creativity and innovation among their employees by identifying their employees' openness to experience, autonomy, and techno-invasion.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENT

This research has been supported by the Slovenian Research and Innovation Agency (ARIS) (Core Project Funding P5-0441 and J7-50185 and J5-4574).

CONFLICT OF INTEREST

The authors have no relevant financial or non-financial interests to disclose.

ETHICS STATEMENT

Being anonymous and noninvasive, the study is exempt from the ethics approval.

Open Research

DATA AVAILABILITY STATEMENT

Data are available upon request from any of the authors.