Successful radiofrequency ablation via transseptal approach for premature ventricular contractions originating from left ventricular outflow tract following self-expanding transcatheter aortic valve implantation

Graphical Abstract

Transseptal catheter ablation resolved ventricular arrhythmias originating from the left ventricular outflow tract following transcatheter aortic valve implantation with a self-expanding Evolut valve. This report highlights the transseptal approach as a safe and effective alternative, overcoming the structural complexities of self-expanding valves while reducing procedural risks and preserving valve integrity.

Transcatheter aortic valve implantation (TAVI) has become a standard treatment for severe aortic stenosis, particularly in elderly patients. While conduction abnormalities are well-established complications of TAVI,1 reports of ventricular arrhythmias (VAs) following the procedure remain exceedingly rare. Furthermore, catheter ablation for VAs post-TAVI has only been documented in a few cases, all involving balloon-expandable valves (SAPIEN valve, Edwards Lifesciences, Irvine, CA) and performed via a transaortic approach.2, 3 Herein, we report the first known case of catheter ablation for VAs following the implantation of a self-expanding valve (Evolut valve; Medtronic, Minneapolis, MN, USA), utilizing a transseptal approach rather than the conventional transaortic approach.

An 83-year-old woman presented with dyspnea and palpitations 3 years after undergoing TAVI (Evolut Pro+26 mm; Medtronic) for the treatment of severe aortic stenosis. A 24-h Holter ECG revealed PVCs comprising 24.3% of all beats. Despite bisoprolol (2.5 mg/day) and flecainide (50 mg twice daily), PVC burden and symptoms remained unchanged. Therefore, we decided to proceed with catheter ablation for drug-refractory symptomatic frequent PVCs.

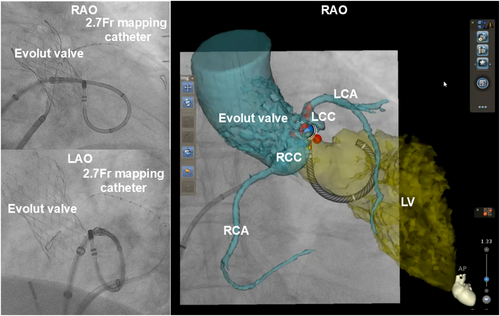

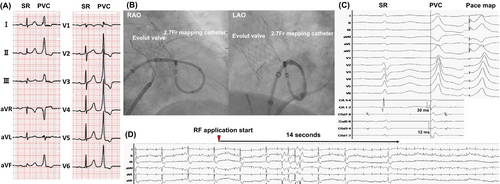

The ECG revealed high R-wave amplitude in the inferior leads and an early transition zone shifting from lead V1 to V2 during sinus rhythm, suggesting PVCs originating from the left ventricular outflow tract (LVOT), including the aortomitral continuity (AMC) (Figure 1A). The procedure was performed under intracardiac echocardiography (ICE) guidance (SOUNDSTAR; Biosense Webster) using the CARTO3 mapping system and QDOT Micro catheter (Biosense Webster). To minimize valve-related risks and difficulties, a transseptal approach was selected over a transaortic approach. A 2.7-Fr microcatheter (EPstar Fix AIV; Japan Lifeline) was placed in the anterior interventricular vein to assist in detailed mapping (Figure 1B).

Under ICE, a transseptal puncture was successfully performed, and a Vizigo sheath (Biosense Webster) advanced into the left atrium. The ablation catheter, shaped into a U-curve, targeted the AMC (Figure 1B). During PVCs, the local bipolar activation potential recorded by the ablation catheter preceded the QRS onset by 30 ms, which was earlier than the 12 ms recorded by the microcatheter (Figure 1C). A good pacemap was obtained from the ablation catheter (Figure 1C).

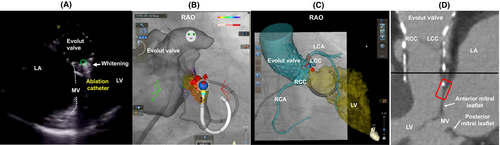

Radiofrequency ablation (35 W, 60 s) resulted in the immediate cessation of PVCs within 14 s (Figure 1D). Eight additional lesions were delivered to adjacent sites, with ICE confirming the whitening of the ablated areas (Figure 2A). During isoproterenol infusion, no recurrence of PVCs was observed, and the procedure was successfully completed without complications. At the 6-month follow-up, Holter monitoring showed a dramatic reduction in PVC burden to 0.001% of total beats, with no evidence of structural valve dysfunction.

Catheter ablation for VAs originating from the LVOT, AMC, or aortic cusps after TAVI has only been reported in cases involving balloon-expandable valves.2-4 To date, there are no documented cases of ablation targeting VAs following the implantation of self-expanding valves.

The structural differences between self-expanding Evolut valves and balloon-expandable SAPIEN valves significantly impact on catheter navigation when the transaortic (trans-TAVI valve) approach is used. The Evolut valve is characterized by supra-annular leaflets, while the SAPIEN valve has intra-annular leaflets. Additionally, the Evolut valve's smaller cell size (10 Fr, compared to 13–20 Fr for the SAPIEN valve) and longer stent frame present substantial challenges for catheter manipulation in the transaortic approach. These design features make it particularly difficult to navigate an ablation catheter through the valve cells or along its edges to access the native aortic cusps. Although successful ablation using catheter techniques tailored to balloon-expandable valves has been reported, these methods are nearly infeasible with the Evolut valve due to its structural constraints.

For these reasons, selecting the transseptal approach as the first-line strategy in this case was appropriate. Indeed, a previous study reports that VAs originating from the LVOT can be accessed and treated via a transseptal approach using an ablation catheter configured in a reversed S-curve.5 This approach successfully suppressed PVCs; however, if it had been unsuccessful, an alternative strategy, such as the transaortic (trans-TAVI valve) approach, could have been considered. A trans-TAVI valve approach to access the left ventricle poses risks such as valve migration and structural dysfunction. In post-TAVI cases, traditional catheter looping via the aortic cusps during valve opening is not feasible.4 Instead, a straight catheter trajectory must be employed, but this is hindered by the high commissural posts and tall frame of the Evolut valve. These structural features might increase the technical challenges of trans-Evolut ablation compared to trans-SAPIEN procedures.

The PVCs appeared 3 years after TAVI, making acute tissue injury an unlikely cause. The successful ablation site was located adjacent to the lower left edge of the Evolut valve (Figure 2B–D), which may suggest a relationship with the valve's self-expanding design and its slightly ventricular position within the left ventricle. These factors could have created an arrhythmogenic substrate, although the precise mechanism remains unclear.

Electrophysiologists must carefully consider the type of TAVI valve when selecting the ablation strategy. This case highlights LVOT ablation via a transseptal approach as an effective method for managing LVOT arrhythmias while minimizing valve-related risks.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank Dr. Jungo Kasai for editing a draft of this manuscript.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST STATEMENT

Dr. Hachinohe is a clinical proctor for Edwards Lifesciences, Abbott Medical, and Medtronic. The remaining authors have nothing to disclose.

ETHICS APPROVAL STATEMENT

This research was conducted according to the principles of the Declaration of Helsinki.

PATIENT CONSENT STATEMENT

The patient provided written informed consent to publication of the details of her case.

Open Research

DATA AVAILABILITY STATEMENT

The authors confirm that all the data supporting the findings of this research are available within the article.