Analytical evaluation of the automated genotyping system (GenPlex) compared to a traditional real-time PCR assay for the detection of high-risk human papillomaviruses

Lijuan Zhang, Yan Ju, and Haixu Hu contributed equally to this study.

Abstract

The detection of high-risk human papillomaviruses (HPVs) is crucial for early screening and preventing cervical cancer. However, the substantial workload in high-level hospitals or the limited resources in primary-level hospitals hinder widespread testing. To address this issue, we explored a sample-to-answer genotyping system and assessed its performance by comparing it with the traditional real-time polymerase chain reaction (PCR) method conducted manually. Samples randomly selected from those undergoing routine real-time PCR detection were re-analyzed using the fully automatic GenPlex® system. This system identifies 24 types of HPV through a combination of ordinary PCR and microarray-based reverse hybridization. Inconsistent results were confirmed by repeated testing with both methods, and the κ concordance test was employed to evaluate differences between the two methods. A total of 365 samples were randomly selected from 7259 women. According to real-time PCR results, 76 were high-risk HPV negative, and 289 were positive. The GenPlex® system achieved a κ value greater than 0.9 (ranging from 0.920 to 1.000, p < 0.0001) for 14 types of high-risk HPV, except HPV 51 (κ = 0.697, p < 0.0001). However, the inconsistent results in high-risk HPV 51 were revealed to be false positive in real-time PCR by other method. When counting by samples without discriminating the high-risk HPV type, the results of both methods were entirely consistent (κ = 1.000, p < 0.0001). Notably, the GenPlex® system identified more positive cases, with 73 having an HPV type not covered by real-time PCR, and 20 potentially due to low DNA concentration undetectable by the latter. Compared with the routinely used real-time PCR assay, the GenPlex® system demonstrated high consistency. Importantly, the system's advantages in automatic operation and a sealed lab-on-chip format respectively reduce manual work and prevent aerosol pollution. For widespread use of GenPlex® system, formal clinical validation following international criteria should be warranted.

1 INTRODUCTION

Cervical cancer is a prevalent malignant tumor affecting females globally, ranking fourth in both morbidity and mortality.1, 2 Fortunately, cervical cancer stands as the sole tumor with a definite pathogeny, attributed to the persistent infection of high-risk human papillomaviruses (HPVs), providing a significant opportunity for prevention through early screening and vaccination.3-5 Presently, over 450 HPV types have been identified, with HPV 16, 18, 31, 33, 35, 39, 45, 51, 52, 53, 56, 58, 59, 66, 68, 73, 82, and 83 categorized as high-risk for cervical cancer. Additionally, HPV 6, 11, 42, 43, 44, and 81 are associated with genital warts and are considered low risk for cervical cancer.6-8 It is well-established that the probability of developing cervical cancer is extremely low in the absence of high-risk HPV infection. For women who experience transient infections, the risk of cervical cancer is minimal. Only a small percentage of women with persistent high-risk HPV infections may progress to cervical cancer.9-12 Therefore, routine detection of high-risk HPV plays a crucial role in preventing cervical cancer and has become widely accepted as a routine test in medical organizations.

Various molecular methods, including hybrid capture,13, 14 sequencing,15, 16 flow-through hybridization,17, 18 real-time polymerase chain reaction (PCR),19, 20 loop-mediated isothermal amplification,21, 22 and digital PCR,23, 24 have been successfully applied to HPV detection. Among these, real-time PCR is the most commonly used owing to its superior accuracy and reproducibility.25-27 However, to identify each clinically relevant HPV type, at least five reaction tubes (four for high risk and one for low risk) are required for one sample because of the limited fluorescent channels in each reaction (usually no more than five). This increases the workload and poses a staff shortage, particularly when dealing with dozens or hundreds of samples daily. Even though the assay could be simplified to one reaction tube, it lacks information for treatment decision-making as it only detects high-risk HPV without distinguishing the type or only discriminates HPV 16 and 18, which have the highest risk. Additionally, many potentially infected individuals may initially choose to visit community or primary-level hospitals, which are often not equipped with specialized PCR labs, leading to missed opportunities for detection.

To address these challenges, we aimed to find a technique that could automate the detection process. GenPlex® is a sample-to-answer HPV genotyping system capable of processing up to 24 samples/run within 3.5 h, discriminating 18 types of high-risk HPV (16, 18, 31, 33, 35, 39, 45, 51, 52, 53, 56, 58, 59, 66, 68, 73, 82, and 83) and six types of low-risk HPV (6, 11, 42, 43, 44, and 81) in a single test.28, 29 Importantly, all procedures are performed automatically in a sealed microfluidics biochip that integrates sample lysis, DNA extraction, PCR, membrane reverse blot hybridization, and waste storage. This efficient system saves labor and minimizes aerosol pollution. It is suitable for labs with heavy testing tasks and local hospitals lacking PCR labs and skilled technicians.

In this study, we evaluated the performance of the GenPlex® system in detecting high-risk HPV by comparing it with the real-time PCR assay routinely used in our center. Both methods had passed the clinical validation of Chinese National Medical Products Administration (NMPA) and Conformité Européenne (CE). Our data demonstrated high consistency between the two methods, but the GenPlex® system could identify more subtypes of HPV and exhibited clear advantages in terms of convenient operation.

2 PATIENTS AND METHODS

2.1 Patients

Women undergoing routine high-risk HPV examinations at the Fifth Medical Center of the Chinese PLA General Hospital were selected for this study. Cervical secretions were collected using a cell brush and stored at 4°C in storage buffer until analyzed by either the real-time PCR assay or GenPlex® system. The study received approval from the Ethics and Scientific Committee of the Fifth Medical Center of the Chinese PLA General Hospital. All patients provided informed consent upon admission, allowing the use of their samples for further investigation.

2.2 High-risk HPV detection by real-time PCR assay

The process was carried out following the manufacturer's instructions (Shanghai ZJ Bio-Tech Co), as previously described.22 Briefly, after uniform mixing, 600 μL of the samples were transferred into 1.5 mL Eppendorf tubes and centrifuged at 13 000 revolutions per minute (rpm) for 5 min. After removing the supernatant and adding 1 mL of saline injection, the samples were centrifuged at 13 000 rpm for 5 min. The supernatant was then removed, and 100 μL of nucleic acid extraction reagent was added. After thorough mixing, the samples were heated in a metal bath at 100°C for 10 min. Subsequently, the samples were centrifuged at 13 000 rpm for 5 min, and the supernatant containing the DNA template was analyzed by the High-risk HPV Genotyping Real-Time PCR Kit on the SLAN-96P Real-Time PCR System (Shanghai Hongshi Medical Technology Co., Ltd). Each sample underwent testing in four separate tubes, with Tube 1 containing HPV 16/56/31/internal control (IC), Tube 2 containing HPV 18/52/58/68, Tube 3 containing HPV 45/82/33/35, and Tube 4 containing HPV 39/51/59/66. Each tube comprised 0.4 μL of enzymes, 4 μL of DNA template (or positive and negative control), and 36 μL of the mixed solution. The reaction conditions were as follows: 94°C for 2 min; 93°C for 10 s, 62°C for 31 s, for 40 cycles. Fluorescence signals of FAM/VIC/ROX/CY5 were collected at 62°C. When all controls were qualified, a relative value was calculated as follows: the cycle threshold (Ct) of the HPV minus the Ct of IC plus 28. A relative Ct value of <40 and ≥40 could be defined as positive and negative, respectively.

2.3 HPV detection by using the GenPlex® system

Samples were selected using a stratified random sampling method from those underwent real-time PCR detection and were reanalyzed by the GenPlex® system (Beijing Bohui Innovation Biotechnology Group Co., Ltd). For each type of high-risk HPV, a minimum of 20 randomly selected positive samples were required (except for HPV45, which had an insufficient number of samples to choose from). The GenPlex® system detects the L1 region of HPV and consists of three parts: the microfluidic DNA chips, the matching reagents, and a nucleic acid detector (GenPlex controller). Following the manufacturer's instructions, all reagents were brought to room temperature, and the microfluidic chips were manually loaded into the corresponding place in the GenPlex controller. After uniform mixing, 200 μL of the samples were transferred into the sample holes on the chips. The cabin door was then closed, and “go” was pressed on the manipulate screen to start the entire process with no further manual operation. Target DNA extraction, PCR amplification, and reverse dot hybridization were carried out automatically under the drive of a micropump. The hybridization membrane of the detection area was coated with detection probes for 24 HPV subtypes. If the amplification product contained the target gene, it could be captured by the probe on the chip, showing spots in the specific position. For each run, up to 24 samples (six chips, each loaded with four samples) could be tested within 3.5 h. When the process was finished, the system would automatically report the results, which could be checked by the operators according to the probe distribution shown in Table 1. In addition to HPV genotyping probes, quality control probes were also integrated on the chip to ensure the reliability of the results: blank and negative control (BC and NC) in the top left corner of the chip eliminated false-positive results caused by aerosol pollution or incorrect operation; low, medium, and high internal control (IC, β-globin) in the left third row of the chip demonstrated the quality of DNA extraction, purification, and amplification; color development quality Spot control (SP) in the other three corners of the chip indicated the effect of hybridization.28 One type of HPV could be identified when all controls were valid, and a colored dot was observed in the corresponding position on the chip.

| BC | 11 | IC1 | 68 | 56 | 45 | 31 | SP2 |

| NC | 42 | IC2 | 73 | 58 | 51 | 33 | 16 |

| 81 | 43 | IC3 | 82 | 59 | 52 | 35 | 18 |

| SP1 | 44 | 6 | 83 | 66 | 53 | 39 | SP3 |

- Abbreviations: BC, blank control; IC, internal control; NC, negative control; SP, color development quality Spot control.

2.4 Comparison between two methods and statistical analysis

In cases where inconsistent results were observed in the comparison, samples were subjected to repeated testing by both methods to confirm the findings. Using the results of the real-time PCR assay as the reference, the GenPlex® system's sensitivity, specificity, positive predictive value, negative predictive value, and overall agreement were calculated. Additionally, the consistency between the two methods was assessed using a κ concordance test. κ values falling within the ranges of 0.0–0.20, 0.21–0.40, 0.41–0.60, 0.61–0.80, and 0.81–1.00 were categorized as poor, fair, moderate, good, and very good agreement, respectively. The McNemar's test was employed to determine whether there were statistical differences between the real-time PCR and GenPlex® system results. Furthermore, the Fisher exact test was utilized to assess whether statistical differences existed when detecting high-risk HPV 51 with or without the coexistence of high-risk HPV 59. All analyses were conducted using SPSS Statistics 24.0 (IBM Corporation), and p values < 0.05 were considered statistically significant.

3 RESULTS

3.1 Patients and samples

In total, cervical samples were collected from 7259 women (age range: 13–95 years) treated from November 2021 to February 2023 in our center for the present study. All samples were tested in the laboratory of the Senior Department of Oncology using the real-time PCR high-risk HPV assay, revealing a positive rate of 18.0% (1310/7259). Among the positive samples, 77.3% (1013/1310) were single-type HPV, while the remaining 22.7% (297/1310) consisted of mixed infections with more than two types of HPV. The most commonly identified types were high-risk HPV 52 (302 cases), 58 (245 cases), and 16 (202 cases), consistent with previous reports.18, 20 Conversely, high-risk HPV 35 (48 cases), 82 (25 cases), and 45 (17 cases) were relatively rare.

For the present study, 365 samples (289 positive and 76 negative) were randomly selected from the aforementioned women (age range: 23–77 years) and reanalyzed by the GenPlex® system in the laboratory of the Senior Department of Oncology. According to the results of the real-time PCR, 69.2% (200/289) of the high-risk HPV-positive samples were single type, 21.8% (63/289) had mixed infections with two types, 5.2% (15/289) with three types, 3.5% (10/289) with four types, and 0.3% (1/289) with five types. When counting by high-risk HPV-positive types, there were a total of 416 tests. The detailed test numbers for each type can be found in Table 2, revealing that the most common and rare types were high-risk HPV 52 (47 tests) and 45 (16 tests), respectively. Variations in numbers were primarily due to samples with mixed HPV types. Importantly, the clinical treatment of all women was not influenced by the results of the GenPlex® system.

| Type | GenPlex® | qPCR | Se (%) | Sp (%) | PPV (%) | NPV (%) | Ag (%) | κ | p | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| + | –a | |||||||||

| 16 | + | 28 (9) | 3 (0) | 100 | 99.1 | 90.3 | 100 | 99.2 | 0.945 | <0.0001 |

| – | 0 | 334 | ||||||||

| 18 | + | 24 (9) | 0 | 100 | 100 | 100 | 100 | 100 | 1.000 | <0.0001 |

| – | 0 | 341 | ||||||||

| 31 | + | 21 (10) | 0 | 100 | 100 | 100 | 100 | 100 | 1.000 | <0.0001 |

| – | 0 | 344 | ||||||||

| 33 | + | 21 (8) | 1 (0) | 100 | 99.7 | 95.5 | 100 | 99.7 | 0.975 | <0.0001 |

| – | 0 | 343 | ||||||||

| 35 | + | 23 (10) | 0 | 100 | 100 | 100 | 100 | 100 | 1.000 | <0.0001 |

| – | 0 | 342 | ||||||||

| 39 | + | 23 (10) | 0 | 95.8 | 100 | 100 | 99.7 | 99.7 | 0.977 | <0.0001 |

| – | 1 (1) | 341 | ||||||||

| 45 | + | 16 (10) | 0 | 100 | 100 | 100 | 100 | 100 | 1.000 | <0.0001 |

| – | 0 | 349 | ||||||||

| 51 | + | 22 (10) | 4 (1) | 62.9 | 98.8 | 84.6 | 96.2 | 95.3 | 0.697 | <0.0001 |

| – | 13 (13) | 326 | ||||||||

| 52 | + | 46 (30) | 4 (1) | 97.9 | 98.7 | 92 | 99.7 | 98.6 | 0.941 | <0.0001 |

| – | 1 (1) | 314 | ||||||||

| 56 | + | 28 (17) | 0 | 90.3 | 100 | 100 | 99.1 | 99.2 | 0.945 | <0.0001 |

| – | 3 (3) | 334 | ||||||||

| 58 | + | 38 (23) | 0 | 100 | 100 | 100 | 100 | 100 | 1.000 | <0.0001 |

| – | 0 | 327 | ||||||||

| 59 | + | 33 (21) | 2 (1) | 97.1 | 99.4 | 94.3 | 99.7 | 99.2 | 0.952 | <0.0001 |

| – | 1 (1) | 329 | ||||||||

| 66 | + | 28 (11) | 0 | 96.6 | 100 | 100 | 99.7 | 99.7 | 0.981 | <0.0001 |

| – | 1 (1) | 336 | ||||||||

| 68 | + | 25 (10) | 4 (1) | 100 | 98.8 | 86.2 | 100 | 98.9 | 0.920 | <0.0001 |

| – | 0 | 336 | ||||||||

| 82 | + | 19 (7) | 2 (1) | 95.0 | 99.4 | 90.5 | 99.7 | 99.2 | 0.922 | <0.0001 |

| – | 1 (1) | 343 | ||||||||

| Total | + | 289 (89b) | 0 | 100 | 100 | 100 | 100 | 100 | 1.000 | <0.0001 |

| – | 0 | 76 | ||||||||

- Abbreviations: Ag, agreement; NPV, negative predictive value; PPV, positive predictive value; qPCR, quantitative polymerase chain reaction; Se, sensitivity; Sp, specificity.

- a The negative sample number in each type is the sum of the total negative plus the number negative for that type.

- b The number in parentheses represents samples detected as mixed types by the real-time PCR method. The total number may not equal the sum of that number in each type because one sample may mix with more than two types of high-risk human papillomavirus.

3.2 Comparison between real-time PCR and the GenPlex® system

The head-to-head comparison of each sample is detailed in Table S1, confirming the successful testing of all samples. Real-time PCR assay was considered the gold standard in this comparison as it was routinely used in our center. However, it is important to note that real-time PCR may not be the ideal gold standard owing to potential differences in DNA extraction, HPV type coverage, detection limits, and other factors. This limitation is acknowledged in our study.

Based on the summarized data in Table 2, high-risk HPV types 18, 31, 35, 45, and 58 exhibited optimal performance, with complete agreement between the two methods (κ value of 1.0, p < 0.0001). High-risk HPV types 16, 33, and 68 showed slightly lower performance than the aforementioned types (κ value of 0.945, 0.975, and 0.920, respectively, p < 0.0001), with 100% sensitivity for positive results but some discrepancies in negative results (specificity of 99.1%, 98.8%, and 99.7%, respectively). Similar performance was observed for high-risk HPV types 39, 56, and 66 (κ value of 0.977, 0.945, and 0.981, respectively, p < 0.0001), with 100% specificity for negative results but some missed positive results (sensitivity of 95.8%, 90.3%, and 96.6%, respectively). High-risk HPV types 52, 59, and 82 demonstrated good performance despite occasional inconsistencies in both positive and negative results (κ value of 0.941, 0.952, and 0.922, respectively, p < 0.0001). The most significant disagreement was observed in high-risk HPV 51, achieving a sensitivity of 62.9% and specificity of 98.8% (κ value of 0.697, p < 0.0001). Importantly, these disagreements were specific to individual types; when considering samples without discriminating the HPV type, the two methods showed complete consistency (κ value of 1.0, p < 0.0001).

Furthermore, the GenPlex® system identified 73 cases of other HPV types not covered by the real-time PCR assay, including low-risk HPV 6 (n = 2), 11 (n = 1), 42 (n = 18), 43 (n = 4), 44 (n = 11), and 81 (n = 18), as well as high-risk HPV 53 (n = 16), 73 (n = 2), and 83 (n = 1). These cases were all accompanied by other high-risk HPV except sample No. 118, which was negative in real-time PCR assay but showed low-risk HPV 44 positive in GenPlex® system. The above data indicated that HPV 6, 11, 42, 43, 44, 53, 73, 81, and 83 were fairly common and should not be overlooked in routine detection.

3.3 Inconsistent results and their potential reasons

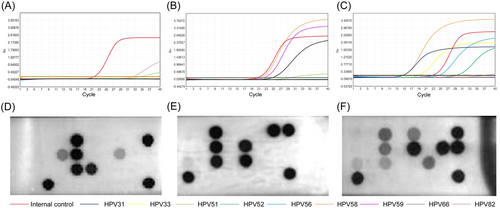

The inconsistent results were confirmed through repeated testing using both methods and detailed in Table S3. A representation of typical results is demonstrated in Figure 1.

Overall, 21 positive results that defined by real-time PCR were missed by GenPlex® system, including high-risk HPV 39 (n = 1), 51 (n = 13), 52 (n = 1), 56 (n = 3), 59 (n = 1), 66 (n = 1), and 82 (n = 1). Among them, high-risk HPV 51 should pay more attention (see example in Figure 1B,E), which demonstrated that 13 cases of inconsistency were all accompanied with high concentration of high-risk HPV 59 (the relative Ct value of of high-risk HPV 59 in all these samples were <30). In contrast, this situation was not observed in other high-risk HPV 51 positive samples, no matter single (n = 12) or mixed types (n = 10) aside from high-risk HPV 59. Fisher's exact test revealed the detection of high-risk HPV 51 was statistically different when it was accompanied with or without high-risk HPV 59 (p < 0.001). To confirm this observation that not been reported by previous literature, additional 12 samples with mixed high-risk HPV 51 and 59 that defined by real-time PCR were re-tested by GenPlex® system, which again reached a negative result in high-risk HPV 51. Interestingly, further analysis by ordinary PCR and gel electrophoresis in E6/E7 region revealed the results of high-risk HPV 51 in real-time PCR were false positive (see Table S4 for details). Therefore, the results of GenPlex® system would be more trustworthy. Concerning the inconsistency in high-risk HPV 39, 52, 56, 59, 66, and 82, the reason may be due to normal error or mutual interference between different types, but the inconsistent results were too few to figure out the inherent law.

Meanwhile, 20 negative cases that defined by real-time PCR were found positive by GenPlex® system, including high-risk HPV 16 (n = 3), 33 (n = 1), 51 (n = 4), 52 (n = 4), 59 (n = 2), 68 (n = 4) and 82 (n = 2). They were definitely not false positive results because all quality controls were ensured work. Notably, 80% (16/20) of them (only HPV 59 in sample No. 10, HPV 16 in sample No. 156, HPV 68 and 82 in sample No. 324 were not included) had a relative Ct value > 40 in real-time PCR, indicating HPV of that type may really present but its concentration was too low to generate a positive result (e.g., the result of sample No. 110 in Figure 1A). Their corresponding results in GenPlex® system provided further evidence to above assumption, namely, 65.5% (13/20) of them (HPV 16, n = 2; HPV 33, n = 1; HPV 51, n = 4; HPV 52, n = 2; HPV 59, n = 1; HPV 68, n = 1; HPV 82, n = 2) had a colored dot that obviously weak than the controls (e.g., the result of sample No. 110 in Figure 1D). Although more evidence is needed in the future, these data suggest that the GenPlex® system might be more sensitive than real-time PCR and could identify more positive samples with low DNA concentration.

4 DISCUSSION

Regular high-risk HPV testing for female adults is widely accepted for its significant role in preventing cervical cancer.9-12 While real-time PCR is a common method for high-risk HPV testing, the lack of professional labs and skilled technicians has hindered its use in primary-level hospitals, leading to overcrowding in higher level institutions. The GenPlex® system, verified in this study, presents a potential solution to this issue.

For primary-level hospitals with limited resources, the GenPlex® system eliminates the need for professional labs and skilled technicians. The system's chip integrates separate areas for sample preparation, DNA amplification, and product analysis, simulating the functions of a professional PCR lab.28 The entire process is sealed, preventing the risk of aerosol pollution. The manual operation is simple, requiring only reagent and sample loading, making it accessible to individuals with minimal experience after basic training. With the GenPlex® system, primary-level hospitals can conduct HPV tests easily and accurately, providing significant convenience for local residents.

For high-level hospitals with heavy workloads, the GenPlex® system can greatly alleviate the burden on technicians. Properly arranged, one machine can identify 18 types of high-risk HPV and six types of low-risk HPV for at least 72 samples in a workday (each one batch in the morning and afternoon, another one batch was performed before getting off work and checked in the next morning), providing sufficient throughput for most high-level hospitals. Importantly, the manual operation time for one batch is less than 5 min, significantly shorter than the manual operation time in real-time PCR assays (greater than 50 min). This allows technicians more time for other tasks. Moreover, the study's data show high consistency between the results of the GenPlex® system and real-time PCR, especially when not distinguishing between HPV types (κ = 1.0, p < 0.0001), indicating its suitability for routine practice.

PCR amplification of HPV DNA is a crucial step in both real-time PCR assays and the GenPlex® system. The main difference lies in the strategy used to read the PCR product. Real-time PCR assays use Taqman fluorescence probes, which, while specific, are limited in available fluorescence channels for one reaction. To recognize a dozen of HPV types, at least four reactions were needed for one sample, which would increase the workload and cost.19, 20, 22 In contrast, the GenPlex® system employs microarray-based reverse hybridization technology, requiring only one PCR to recognize HPV types through probes distributed on specific locations on the chip. This allows the system to easily detect up to 24 types of HPV with lower workload and cost.28, 29 Benefiting from the genotyping chip, the GenPlex® system identified 73 cases of other HPV types not covered by real-time PCR, including 54 cases of low-risk HPV and 19 cases of high-risk HPV.

Notably, despite low-risk HPV 6 and 11 being commonly recommended in condyloma acuminatum diagnosis, their detection rate was noticeably lower than that of low-risk HPV 42, 44, and 81. This could be attributed to the higher tendency of HPV 42, 44, and 81 to coexist with high-risk HPV compared to HPV 6 and 11. Previous reports have highlighted that the detection rate of low-risk HPV 6 and 11 is not the highest,18 emphasizing the importance of not neglecting other low-risk HPV types in routine testing. For high-risk types, HPV 53 stood out with a detection rate comparable to the 15 classical types of high-risk HPV. In contrast, high-risk HPV 73 and 83 showed lower incidences with only two and one cases, respectively. While not high in frequency, these cases should not be dismissed, especially considering a large population base. Based on this data, we recommend the GenPlex® system for routine clinical practice as it may provide more comprehensive information for treatment decision-making. In addition, this recommendation finds support in the false positive and false negative cases that detected by real-time PCR assay.

As we had mentioned before, real-time PCR assay was not the ideal gold standard because it could not ensure the absolute accuracy. Potential differences in DNA extraction, HPV type coverage, detection limits, and other factors could all attribute to the result variation, which may interfere the validity of the judgment. For example, the 13 inconsistent cases in high-risk HPV 51 were initially considered as the consequence of inhibition by high-risk HPV 59 in GenPlex® system (p < 0.001). However, with the assistance of ordinary PCR that amplified the E6/E7 region of high-risk HPV 51, these cases were revealed actually to be false positive in real-time PCR assay and the results of GenPlex® system were more trustworthy. According to our data, when a sample was detected as mixed high-risk HPV 51 and 59 in real-time PCR assay, attention should be paid to avoid the false detection in high-risk HPV 51.

For the 20 missed cases in real-time PCR, no clear distribution was exhibited in specific HPV types, indicating they were random events. Further analysis revealed that most of these cases had weak signals in real-time PCR, with relative Ct values exceeding the cutoff after adjustment with the IC. Additionally, most of the corresponding types showed weak coloration in the GenPlex® system. Collectively, the evidence suggests that these inconsistent cases were due to low DNA concentration. Our data suggest that the GenPlex® system may be more sensitive than real-time PCR in such samples, although further verification is warranted. To test this speculation, digital PCR could be explored, as it offers advantages in high sensitivity and absolute quantification. Digital PCR has the potential not only to quantify HPV DNA load in cervical secretions but also to predict early relapse of cervical cancer through plasma samples.30-32 As of now, a digital PCR assay covering 15 or 18 types of high-risk HPV is not available, making it a prospective focus for our research team in the future.

One limitation of present study is the GenPlex® system was not evaluated according to the validation guidelines for candidate HPV assays described by Meijer et al.33 This was because the two methods in present study had both passed the clinical validation of NMPA and was allowed to be used in medical organizations of China for cervical cancer screening. Besides, the results of both methods were entirely consistent (κ = 1.000, p < 0.0001) when counting by samples without discriminating the high-risk HPV type. Therefore, the two methods were compared directely in randomly selected samples and no clinial information of the samples was included to confirm the inconsistent results. Nevertheless, for widespread use of GenPlex® system, a formal clinical validation following international criteria should be warrantied

5 CONCLUSION

The GenPlex® system demonstrated a higher level of consistency in high-risk HPV detection than traditional real-time PCR assays. When evaluating each high-risk HPV type individually, the GenPlex® system achieved a κ value greater than 0.9 for 14 types, except HPV 51. However, the inconsistent results in high-risk HPV 51 were revealed to be false positive in real-time PCR by other method. When considering samples collectively, the results of the two methods were in full agreement (κ = 1.0, p < 0.0001). Moreover, the GenPlex® system could identify more positive cases that were not covered by real-time PCR assays or were in low DNA concentration. Importantly, the system's advantages in automatic operation and sealed lab-on-chip design could significantly reduce manual work and prevent aerosol pollution. For widespread use of GenPlex® system, formal clinical validation following international criteria should be warranted.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

Yi Liu and Lihong Bian contributed to the study design and practical coordination. Lijuan Zhang and Yan Ju performed data analysis. Haixu Hu, Chunhui Ma, and Yanju Yu conducted sample detection. Yan Huang, Lili Gong, Wei Zhao, and Yujia Liu collected the samples. Yi Liu wrote the manuscript. All authors reviewed and/or edited the manuscript. All coauthors approved the final manuscript and its submission to this journal.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This study was supported by the Beijing Municipal Science and Technology Commission (No. Z161100000516182).

CONFLICT OF INTEREST STATEMENT

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Open Research

DATA AVAILABILITY STATEMENT

No data were deposited in a repository.