Epidemiology of Influenza among patients with influenza-like illness and severe acute respiratory illness in Pakistan: A 10-year surveillance study 2008-17

Abstract

In Pakistan, the burden of influenza was largely unknown, as no formal surveillance system was in place. In 2008, an influenza surveillance system was set up in eight sentinel sites. This study describes the epidemiology of influenza virus using a 10-year surveillance data from 2008 to 2017. Nasopharyngeal/throat swabs were collected from patients with influenza-like illness (ILI) and severe acute respiratory illness (SARI) along with relevant epidemiological information. The samples were tested using real-time reverse transcriptase-polymerase chain reaction for the detection and characterization of influenza viruses. A total of 17 209 samples were tested for influenza, out of which 3552 (20.6%) were positive; 2151/11 239 (19.1%) were patients with ILI, whereas 1401/5970 (23.5%) were patients with SARI. Influenza A/H1N1pdm09 was the predominant strain with 40.6% (n = 1442) followed by influenza B (936, 26.4%). Influenza A/H1N1pdm09 was predominant among the children (5-14 years) and adults (15-64 years). Influenza B strain was predominantly found in the elderly age group (≥ 65 years) accounting for 48% of cases followed by children (2-4 years) accounting for 37% of cases. This 10-year surveillance data provides evidence of influenza activity in the country throughout the year with seasonal winter peaks. The results could be used to strengthen the epidemic preparedness and response plan.

Highlights

-

The study findings allow national policy makers to better prepare for upcoming seasons.

-

The study describes critical features of influenza epidemiology including risk groups and transmission characteristics.The study will support the selection of influenza strains for vaccine production.

-

Influenza viruses affected all age groups and gender and circulated seasonally peaking during the winter months of December through February.

1 INTRODUCTION

Influenza virus infections substantially contribute to global morbidity and mortality especially among those aged < 5 years and ≥ 65 years.1 Every year, globally, 5% to 10% of adults and 20% to 30% of children have influenza illness, and 3 to 5 million individuals suffer from severe influenza, leading to 250 000 to 500 000 deaths.2-5 There are two main types of influenza viruses (A and B) which are responsible for recurrent epidemics.3, 6 In the 2009 pandemic, influenza A/H1N1 led to over 15 000 reported deaths globally.7

In 2001, the World Health Organization (WHO) formulated a Global Agenda for Influenza Surveillance and Control which highlighted the role of influenza surveillance to understand the epidemiology and transmission of the virus.2, 8, 9 Influenza sentinel surveillance which includes the collection of epidemiological and virological data provides a tool to monitor the circulating strains and subtypes of influenza along with its seasonality. This helps in assessing the burden of influenza and rapidly detecting the appearance of novel influenza subtypes in human population.3, 4, 10

Historically, influenza surveillance has focused on outpatient visits for influenza-like illness (ILI) with fever and cough.11 After the 2009 pandemic, WHO recommended the inclusion of patients with a severe acute respiratory infection (SARI) for influenza surveillance.12, 13 Following this, influenza surveillance systems have been established in many countries greatly contributing to the understanding of the virus.2, 4, 14 However, there is considerable variation in the epidemiology of the virus in different settings which needs to be documented.

In Pakistan, influenza surveillance system was established in 2008 which captured information from both ILI and SARI in eight sentinel sites (high burden tertiary level hospitals) across six provinces. Since then, no comprehensive assessment of the surveillance data has been conducted. Previous studies in Pakistan have looked at the molecular epidemiology and clinical factors associated specifically with influenza A(H1N1)pdm09 virus infection during the 2009 to 2010 pandemic.15, 16 Another study analyzed influenza surveillance data for the period 2008 to 2011 in only four sentinel sites.3 Thus, the present study was carried out in eight sentinel sites in Pakistan during 2008 to 2017; (a) to determine the proportion of influenza positivity among patients with ILI and SARI tested, (b) describe the epidemiology (seasonality, age and sex distribution, and circulating strains), and (c) clinical manifestations among confirmed cases. This comprehensive assessment of the surveillance data will offer a better understanding of the influenza epidemiology in the country.

2 MATERIALS AND METHODS

2.1 Study design

This is a descriptive study of routinely collected influenza sentinel surveillance data from eight sentinel sites of Pakistan from 2008 to 2017.

2.2 Study setting

2.2.1 General setting

Pakistan, a South Asian country is the sixth most populous country in the world with a population of ~220 million.17 The country has a tropical to temperate climate and arid conditions in the coastal south. Rainfall varies greatly from year to year, and alternate flooding and drought are common. Health care in Pakistan is provided mainly in the private sector which accounts for approximately 80% of all outpatient visits.18 Influenza has become a serious public health issue especially after the H1N1 pandemic in 2009.19, 20

Influenza vaccination rate in Pakistan is suboptimal due to unaffordable cost, traditional norms, and customs and poor awareness about the vaccine and its benefits. There is no national influenza policy and the vaccine is not a part of the national immunization program.21

2.2.2 Specific setting: influenza surveillance system in Pakistan

Since 1980, there have been sporadic influenza surveillance activities under the National Influenza Center (NIC) at the National Institute of Health (NIH), Islamabad. In 2008, a sentinel lab-based influenza surveillance network was established in collaboration with the US-Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). The Federal Government Services Hospital in Islamabad was the first sentinel site under the network.3 Seven more influenza surveillance sentinel sites in high-load tertiary hospitals across four provinces and two regions have been set up since then. The sentinel sites and their year of incorporation are: King Edward Medical University, Lahore and Hayatabad Medical Complex, Peshawar (2009), Bolan Medical Complex Hospital, Quetta and Civil Hospital, Karachi (2010), Nishter Medical College and Hospital, Multan (2012), District Headquarter, Gilgit (2013) and Abbas Institute of Medical Sciences, Muzaffarabad (2013).

The physicians from the departments of Medicine, Pediatrics, Ear Nose and Throat, and Obstetrics and Gynecology in each of the sentinel sites were sensitized about the surveillance project. In each site, there was a designated laboratory technician under the project for sample collection and shipment to the sentinel site. The laboratory staff and other project staff were trained in sample processing and testing, data entry, and database maintenance. Presumptive cases, that is, ILI or SARI (as per case definition given below) were referred by the physicians in each sentinel site to the assigned technician for throat/nasopharyngeal swab collection. The sample collected was then sent to the National Institute of Health and designated sentinel sites virology laboratories for testing following standard procedures described below. The demographic and clinical data were recorded at the time of sample collection and also validated by cross-checking with the hospital patient records.

2.3 Case definitions

ILI: defined as a person with acute respiratory illness, with a temperature of (>38°C), and cough within past 10 days of onset. SARI: defined as those with acute respiratory illness, measured fever of (>38°C), cough within past 10 days of onset and requiring hospital admission Appendix S1.22

2.4 Laboratory diagnosis

Throat and/or nasopharyngeal swabs collected from presumptive cases were stored at 70°C in 2 to 3 mL viral transport medium (Virocult). RNA was extracted from samples using Qiagen QIAmp Viral RNA mini kit and eluted in 60 µL elution buffer. The samples were analyzed by one-step real-time reverse transcription-polymerase chain reaction (RT-PCR) on Applied Biosystems platform ABI-7500 following recommended US-CDC protocol.11 The assay was performed using AgPath-IDTM one-step RT-PCR (Ambion; California).3 Briefly, 25 μL of PCR mixture containing 0.5 μL each of probe (FAM-labeled), forward and reverse primers, 1 μL of enzyme mix, 12.5 μL of 2X master mix, 5 μL of nuclease-free water and 5 μL of extracted RNA were added for amplification under the following conditions: reverse transcription at 50°C for 30 minutes, Taq inhibitor activation at 95°C for 10 minutes and 45 cycles at 95°C for 15 seconds, and an extension step of 55°C for 31 seconds. Each sample was tested for influenza typing (A and B) and subtyping of influenza A, including seasonal H3 and A/H1N1pdm09. Human ribonuclease P gene was used as an internal positive control for human nucleic acid. No template or negative controls, and positive template controls for all primer/probe sets were included in each run.23 Reagents (primers and probes) and control were supplied by Influenza Reagents Resource, US-CDC for diagnostic testing. Before and after the emergence of influenza A/H1N1/Pdm09, all protocols/primers were updated in accordance with CDC updated protocol.24

3 STATISTICAL ANALYSIS

Data were entered into and analyzed using SPSS (IBM, version 22). Number of cases of ILI and SARI tested and found positive for influenza are presented year-wise. A time-trend graph shows the seasonality (monthly variation) in the number of confirmed cases of influenza and sample positivity. The influenza patients were divided into five groups on the basis of the type of strain identified: A/H1N1, A/H3N2, A(H1N1) pdm09, A (not typed), and influenza B. These strains were compared across time and age groups using a stacked vertical bar diagram. The χ2 test was used to test the association of demographic characteristics and clinical symptoms with influenza positivity. The average caseload, by week, over 10 years was produced by using R package 2.9.2: R script moving epidemic method (MEM) Appendix S2.25

3.1 Ethical considerations

Ethics approval was obtained from The Union Ethics Advisory Group, Paris, France. Administrative approval was obtained from the National Institute of Health-Islamabad Pakistan. As the study involved a review of existing programme deidentified records, waiver of informed consent was obtained.

4 RESULTS

4.1 Results of influenza testing

A total of 17 209 samples were tested for influenza, out of which 3552 (20.6%) were found to be positive: Among ILI, 2151 out of 11 239 samples (19.1%) were positive whereas 1401 cases of influenza came from 5970 patients (23.5%) with SARI. The number of samples tested and found positive for influenza in each year has been described in Table 1. The annual number of samples tested and positive for influenza in different sites have been given in Appendix S3. Sample positivity ranged from 8.7% in 2015 to 24% in 2009 except for 2011 when 44% of samples tested were positive for influenza.

| Influenza-like Illness | Severe acute respiratory infection | Total | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Year of | Total samples tested | Total samples positive | Total samples tested | Total samples positive | Total samples tested | Total samples positive | |||

| testing | n | n | (%) | n | n | (%) | n | n | (%) |

| 2008-09 | 339 | 78 | (23) | 24 | 0 | (0) | 363 | 78 | (21) |

| 2009-10 | 864 | 181 | (21) | 540 | 156 | (29) | 1404 | 337 | (24) |

| 2010-11 | 1854 | 237 | (13) | 321 | 103 | (32) | 2175 | 340 | (16) |

| 2011-12 | 2546 | 965 | (38) | 623 | 429 | (69) | 3169 | 1394 | (44) |

| 2012-13 | 1344 | 187 | (14) | 322 | 53 | (16) | 1666 | 240 | (14) |

| 2013-14 | 1403 | 124 | (09) | 671 | 67 | (10) | 2074 | 191 | (09) |

| 2014-15 | 1535 | 212 | (14) | 752 | 120 | (16) | 2287 | 332 | (15) |

| 2015-16 | 685 | 54 | (08) | 1275 | 117 | (09) | 1960 | 171 | (09) |

| 2016-17 | 669 | 113 | (17) | 1442 | 356 | (25) | 2111 | 469 | (22) |

| Total | 11239 | 2151 | (19) | 5970 | 1401 | (23) | 17209 | 3552 | (21) |

- a Influenza-like illness.

- b Severe acute respiratory illness.

4.2 Characteristics of confirmed influenza cases

Of 3552 influenza cases, more than half were males (1981, 55.8%), belonging to the age group of 15 to 49 years (1575, 44.3%) followed by 5 to 14 years (569, 16.0%). Most of the cases were from Islamabad site (n = 2922, 82.3%). About 39.2% of cases (n = 1394) were reported in the year 2011. Influenza A/H1N1pdm09 was the predominant strain (40.6%, n = 1442) followed by influenza B (936, 26.4%) and influenza A (not typed) with 17.9% (n = 635) (Table 2).

| Characteristics | Confirmed influenza cases from ILIa | Confirmed influenza cases from SARIb | Total confirmed influenza cases | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total | 2229 | (%) | 1323 | (%) | 3552 | (%) | |

| Age group | <2 y | 350 | (15.7) | 150 | (11.3) | 500 | (14.1) |

| 2-4 y | 289 | (13.0) | 146 | (11.0) | 435 | (12.2) | |

| 5-14 y | 437 | (19.6) | 132 | (10.0) | 569 | (16.0) | |

| 15-49 y | 971 | (43.6) | 604 | (45.7) | 1575 | (44.3) | |

| 50-64 y | 96 | (4.3) | 167 | (12.6) | 263 | (7.4) | |

| 65 and above | 86 | (3.9) | 124 | (9.4) | 210 | (5.9) | |

| Sex | Male | 1218 | (54.6) | 763 | (57.7) | 1981 | (55.8) |

| Female | 1011 | (45.4) | 560 | (42.3) | 1571 | (44.2) | |

| Surveillance site | Islamabad | 1822 | (81.7) | 1100 | (83.1) | 2922 | (82.3) |

| Lahore | 70 | (3.1) | 27 | (2.0) | 97 | (2.7) | |

| Karachi | 40 | (1.8) | 31 | (2.3) | 71 | (2.0) | |

| Muzaffarabad | 54 | (2.4) | 29 | (2.2) | 83 | (2.3) | |

| Gilgit | 68 | (3.1) | 14 | (1.1) | 82 | (2.3) | |

| Quetta | 64 | (2.9) | 7 | (0.5) | 71 | (2.0) | |

| Multan | 38 | (1.7) | 102 | (7.7) | 140 | (3.9) | |

| Peshawar | 73 | (3.3) | 13 | (1.0) | 86 | (2.4) | |

| Year | 2008-09 | 78 | (3.5) | 0 | (0.0) | 78 | (2.2) |

| 2009-10 | 181 | (8.1) | 156 | (11.8) | 337 | (9.5) | |

| 2010-11 | 297 | (13.3) | 43 | (3.3) | 340 | (9.6) | |

| 2011-12 | 974 | (43.7) | 420 | (31.7) | 1394 | (39.2) | |

| 2012-13 | 187 | (8.4) | 53 | (4.0) | 240 | (6.8) | |

| 2013-14 | 124 | (5.6) | 67 | (5.1) | 191 | (5.4) | |

| 2014-15 | 212 | (9.5) | 120 | (9.1) | 332 | (9.3) | |

| 2015-16 | 60 | (2.7) | 111 | (8.4) | 171 | (4.8) | |

| 2016-17 | 116 | (5.2) | 353 | (26.7) | 469 | (13.2) | |

| Influenza | A (not typed) | 478 | (21.0) | 157 | (12.0) | 635 | (17.9) |

| Strains | A/H1N1 | 26 | (1.0) | 02 | (0.0) | 28 | (0.8) |

| A/H3N2 | 367 | (16.0) | 144 | (11.0) | 511 | (14.4) | |

| A/H1N1pdm09 | 738 | (33.0) | 704 | (53.0) | 1442 | (40.6) | |

| B | 620 | (28.0) | 31 | (24.0) | 936 | (26.4) | |

- a Influenza-like illness.

- b Severe acute respiratory illness.

4.3 Seasonal distribution of influenza

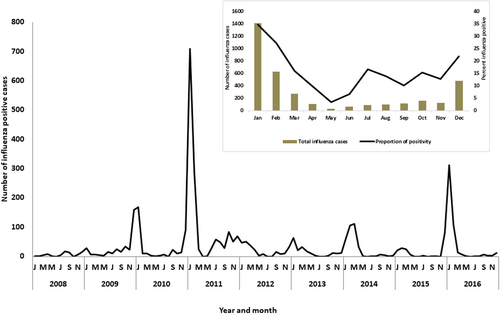

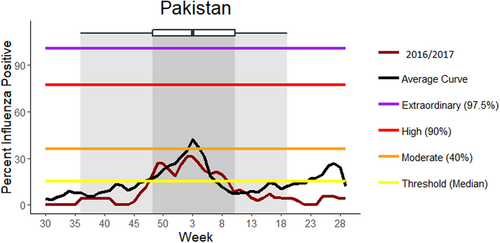

Figure 1 shows that the cases of influenza peaked during the months of December, January, and February with small peaks in the months of July and October in 2011. A delayed seasonal peak was also seen in March 2014. Positivity of samples was highest during the winter months of January (34.8%, 1413/4066), February (27.4%, 626/2287), and December (21.8%, 478/2919). Figure 2 shows the average weekly curve of influenza positivity compared to various threshold levels calculated by the MEM method. The average curve crosses the moderate threshold level during 2 to 5 weeks which corresponds to the month of January to February, whereas it crosses the median threshold level during 45 to 08 weeks corresponding to the months of November to February.

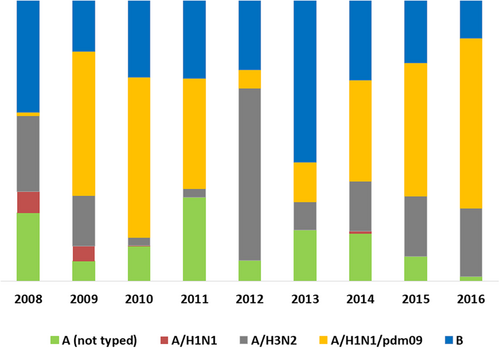

4.4 Time trend and age distribution of different influenza strains

During the pandemic period (2009–2010), the proportion of A/H1N1pdm09 among the positive samples ranged from 51% to 57% followed by influenza B (18-27%). In the pre-pandemic period in 2008, influenza B was the predominant strain (40%). In 2012, influenza A/H3N2 subtype accounted for 61% of the positive samples, whereas, in 2013 influenza B was the predominant strain (58%). During 2014 to 2016, A/H1N1pdm09 was again the most commonly reported influenza subtype ranging from 37% in 2014 to 61% in 2016 (Figure 3).

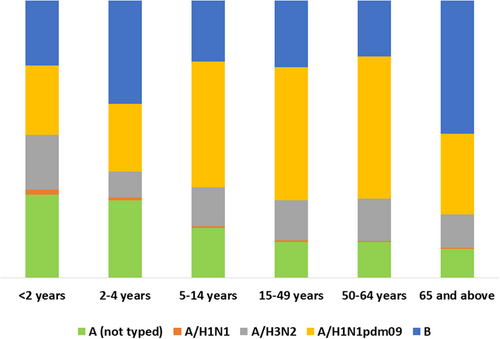

Figure 4 shows the distribution of various influenza strains in different age groups. Influenza A/H1N1 was predominant in the young (14%) and middle-aged adults (32%) in 15 to 64 years accounting for nearly half of all cases in that age group and also in the 5 to 14 years age group (45%). Influenza B was predominant in the elderly age group (≥ 65 years) with 48% of cases followed by children aged 2 to 4 years accounting for 37% of all influenza cases in that age group.

The distribution of influenza strains by the type of surveillance site has been given in Appendix S4.

4.5 Association of clinical symptoms with influenza positivity

Fever and cough were the most common manifestations seen in 88% and 86% of the confirmed influenza cases followed by sore throat (71%) and shortness of breath (46%). Fever and cough together were seen in 82%, fever, and sore throat in 61% whereas fever and shortness of breath were seen in 28% of influenza cases.

Shortness of breath was significantly associated with influenza positivity (P < .001) overall and among patients with ILI. A combination of fever and shortness of breath was significantly associated with influenza positivity among SARI (P < .001). Influenza positivity was significantly lower among those with other symptoms such as fever, sore throat, cough, and their combinations compared to those without these symptoms (Table 3).

| Influenza-like illness | Severe acute respiratory illness | Overall | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Characteristics | Total | Positive (%) | P | Total | Positive (%) | P | Total | Positive (%) | P | |

| Age group | 0-4 y | 3483 | 628 (18) | .001* | 1885 | 307 (16) | .001* | 5368 | 935 (17) | .001* |

| 5-14 y | 2396 | 432 (18) | 1018 | 132 (13) | 3414 | 564 (17) | ||||

| 15-49 y | 4593 | 910 (20) | 2009 | 665 (33) | 6602 | 1575 (24) | ||||

| >50 y | 742 | 178 (24) | 1051 | 295 (28) | 1793 | 473 (26) | ||||

| Sex | Male | 6123 | 1159 (19) | .540 | 3449 | 822 (24) | .440 | 9572 | 1981 (21) | .840 |

| Female | 5116 | 992 (19) | 2521 | 579 (23) | 7637 | 1571 (21) | ||||

| Fever | Yes | 10192 | 1934 (19) | .170 | 5304 | 1189 (22) | .001* | 15496 | 3123 (20) | .001* |

| No | 1047 | 217 (21) | 666 | 212 (32) | 1713 | 429 (25) | ||||

| Cough | Yes | 10178 | 1191 (19) | .002* | 5258 | 1140 (22) | .001* | 15436 | 3051 (20) | .001* |

| No | 1061 | 240 (23) | 712 | 261 (37) | 1773 | 501(28) | ||||

| Sore throat | Yes | 9086 | 1665 (18) | .001* | 3851 | 847(22) | .001* | 12937 | 2512 (19) | .001* |

| No | 2153 | 486(23) | 2119 | 554 (26) | 4247 | 1040 (24) | ||||

| Shortness of breath | Yes | 4274 | 1156 (27) | .001* | 2464 | 370 (15) | .001* | 6738 | 1526 (23) | .001* |

| No | 6965 | 995 (14) | 3506 | 1031 (29) | 10471 | 2026 (19) | ||||

| Fever and cough | Yes | 5028 | 1079 (22) | .001* | 9600 | 1825 (19) | .400 | 14628 | 2904 (20) | .001* |

| No | 942 | 322 (34) | 1639 | 326 (20) | 2581 | 648 (25) | ||||

| Fever and sore throat | Yes | 3261 | 658 (20) | .001* | 8146 | 1503 (19) | .003* | 11470 | 2161 (19) | .001* |

| No | 2709 | 743 (27) | 3693 | 6481 (21) | 5802 | 1391 (24) | ||||

| Fever and shortness of breath | Yes | 1313 | 79 (6) | .001* | 3373 | 922 (27) | .001* | 4686 | 1001 (21) | .150 |

| No | 4657 | 1322 (28) | 7866 | 1229 (16) | 12523 | 2551 (20) | ||||

- * denotes significant association.

There was no gender difference in influenza positivity whereas positivity was significantly higher among adults (15-49 years) and the elderly (≥50 years) compared to children (<15 years) Table 3.

5 DISCUSSION

We found that influenza viruses affected all age groups and gender and circulated seasonally peaking during the winter months of December through February. There were some interesting observations in this study.

A large number of samples were tested in 2011 to 2012 season with high positivity. Two factors may have contributed to this: (a) this was the post-pandemic period with increased virus circulation and heightened surveillance, and (b) the surveillance system which started in 2008 had become more efficient by then.

A majority of cases of influenza came from one site that is, Islamabad, probably because it is a heavy load tertiary care hospital and the surveillance project started from this sentinel site. Also, this was the nodal site in the surveillance project coordinating all other sites and more resources were available here in terms of funding and dedicated project staff. Other sites were dependent on the routine hospital staff. Perhaps, more attention could have been paid to surveillance in other sites.

Surveillance data from Pakistan showed a seasonal pattern of circulation of influenza viruses during winters (December-February) with a peak in January in most seasons. This reflects influenza circulation trends similar to other temperate climates such as in Turkey and Northern China, which have documented high influenza transmission rates during winters.12 Several factors have been proposed to explain the seasonality of influenza, including climatic conditions (temperature and humidity), living environment, host susceptibility, and virus characteristics. Therefore, surveillance data with more information on climatic factors might be helpful to better understand the seasonality of influenza. Our study also reports sporadic influenza cases throughout the year. This pattern is comparable to tropical countries such as Northern Vietnam, Thailand, and Singapore where influenza viruses circulate year round.26 Therefore, we conclude that influenza circulation in Pakistan showed an overlapping pattern of temperate and tropical regions, even though it is geographically located in the temperate region. This has important implications for pandemic preparedness in the country. It calls for round the year monitoring of influenza-related illnesses and deaths and investigation of unusual respiratory disease outbreaks with a special focus during the winter months.

During the immediate post-pandemic period (2010-2011), there continued to be sustained circulation of influenza A/H1N1pdm0927 due to a second wave of Influenza A/H1N1pdm09 in the early part of year 2011 which has been reported from most countries.28 While the exact mechanism for this is not clear, molecular studies suggest that large populations in the tropics can serve as reservoirs of influenza infection throughout the year, with reseeding of drifted viruses possibly leading to outbreaks.29 However, in the later years, during 2012 to 2013, seasonal Influenza B and H3N2 strains were frequently seen mirroring the global picture.30, 31 In recent years (2014-2016), there has been a resurgence of A/H1N1 which is reported globally as well.32-34 This has been attributed to genetic reassortment of the virus, rapid change in environmental conditions and decrease in host immunity.35-37

Pandemic viruses typically infect younger age groups and healthy adults in comparison to seasonal influenza where extremes of age and individuals with comorbid conditions are more susceptible. Similar findings were also reported in this study with detection of A/H1N1pdm09 (pandemic strain) being higher in the younger age group and adults.12 However, influenza B was seen predominantly among the elderly and the young children (<5 years) contrary to other studies which indicates evolving epidemiology of influenza.38

We found no significant gender difference in influenza positivity similar to the findings reported previously in Pakistan.3 But there was significant age-wise difference in influenza positivity with poor positivity among children < 15 years which could be due to other respiratory tract pathogens circulating in this age group such as respiratory syncytial virus, rhinovirus, adenovirus, parainfluenza etc, with similar clinical presentation.13, 39-42 This might also explain the poor performance of the case definitions. Thus, other respiratory viral pathogens should be tested in the surveillance system in future, especially among children.

Besides shortness of breath, other symptoms such as fever, cough, and sore throat were not found to be significant clinical predictors of influenza. Nearly one-fourth of those without fever and cough had influenza which was significantly higher than patients having those symptoms. This calls for a rethinking on the current case definition of suspected cases of influenza. Another possible reason for this finding might be poor adherence to the case definition during patient selection from the sentinel sites which requires adequate training of the project staff and regular monitoring.

About one-fifth of the samples were tested positive for influenza. Other national surveillance systems have reported positivity ranging from 10% to 50% primarily depending on the timing of the activity. Surveillance carried out during the pandemic season (2009-2011) yielded higher positivity compared to those established in the post-pandemic period.13, 16, 43-45 This study also reported a positivity of 44% during the pandemic season reaching upto 50% during the peak period.

Only one-third of the patients were recruited as SARI, similar to previous surveillance assessments due to the global focus on surveillance among patients with ILI.38, 46, 47 This finding was probably because testing of patients with SARI started later in the project after post-pandemic in year 2011. In addition, there were many practical challenges in getting samples from SARI patients due to their ill-health. An important lesson here is that surveillance systems must be prepared enough to capture samples from both ILI and SARI patients in accordance with the WHO recommendations.48, 49 Those with SARI had higher test positivity compared to patients with ILI probably due to the circulation of severe influenza strains. However, the exact reasons could be explored in future research.

There were major strengths in this study. First, the surveillance data presented in this study were part of a well-funded US-CDC supported laboratory-based sentinel surveillance project. Second, the sentinel sites were high-load tertiary care hospitals across all the four provinces of the country. Third, 10-year data (2008-2017) on influenza surveillance in all eight sentinel sites were analyzed. This is a time period long enough to allow a better understanding of the changing transmission dynamics of the virus in the country to guide effective prevention and control measures. Fourth, confirmation of diagnosis of influenza was done using RT-PCR which is the gold standard test. Laboratory procedures of collection of samples, storage, transportation, and testing followed a standard international protocol. Fifth, the surveillance database had a considerable proportion of influenza cases aged less than 5 years who are generally underrepresented in influenza surveillance systems elsewhere.

There were some limitations in this study as well. First, the cases of influenza presented in this study were reported from hospital-based sentinel surveillance sites, thus, missing out an unknown proportion of cases in the community who could not visit the facilities due to poor access or did not require hospital care due to mild symptomatology. Second, the surveillance system did not capture cases who visited the private sector and other levels of health care. Third, this being a hospital-based data, population denominator was not available for estimation of burden of the disease.

6 CONCLUSION

This 10-year influenza surveillance data (2008-2017) in Pakistan provides strong evidence that influenza activity occurs throughout the year with seasonal peaks during the winter season from December to February affecting all age groups and gender. The study finding will support designing of a national influenza pandemic preparedness plan and strengthening the routine surveillance system.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

This study was conducted through the Structured Operational Research and Training Initiative (SORT IT), a global partnership led by the Special Program for Research and Training in Tropical Diseases at the World Health Organization (WHO/TDR). The model is based on a course developed jointly by the International Union Against Tuberculosis and Lung Disease (The Union) and Medécins sans Frontières (MSF/Doctors Without Borders). The specific SORT IT program which resulted in this publication was jointly developed and implemented by: The Union South-East Asia Office, New Delhi, India; the Center for Operational Research, The Union, Paris, France; The Union, Mandalay, Myanmar; The Union, Harare, Zimbabwe; MSF Luxembourg Operational Research (LuxOR); MSF Operational Center Brussels (MSF OCB); Jawaharlal Institute of Postgraduate Medical Education and Research (JIPMER), Puducherry, India; Velammal Medical College Hospital and Research Institute, Madurai, India; National Center for Tuberculosis Control and Prevention, China CDC, Beijing, China; and Khesar Gyalpo University Medical Sciences of Bhutan, Thimpu, Bhutan. We also thank the Centers for Disease Control & Prevention, Atlanta; Virology Department, National Institute of Health, Islamabad; Epidemic Investigation Cell, NIH Islamabad for the financial and technical support provided to support the influenza surveillance system in Pakistan.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

NN, JPT, and CL conceived and designed the study. NN, UBA, NB, and MRM provided laboratory support and collected the surveillance data. NN, JPT, CL, and AY analyzed the data. NN, JPT, and CL interpreted the results, drafted the manuscript and reviewed it. NN, UBA, NB, MRM, SSZZ, MS, and AI critically reviewed the manuscript and provided useful technical inputs. All the authors have read and approved the final draft of the manuscript.

CONFLICT OF INTERESTS

The authors declare that there are no conflict of interests.