Determination of potential biotin interference on accuracy of results of serologic assays for various viral hepatitis markers

Abstract

Biotin taken orally can interfere with some diagnostic immunoassays, including those for thyroid hormones, ferritin, and markers of infectious disease. Assays affected are ones that use streptavidin-biotin in their design. The goal of our study was to examine the effect of biotin concentrations of up to 1200 ng/mL on three serological assays performed on VITROS 3600 system, Immunoglobulin M (IgM) antibodies to hepatitis A virus (anti-HAV), total anti-HAV, and IgM antibodies to hepatitis B virus core antigen (anti-HBc), by spiking serum samples with variable amounts of biotin. No false-negative results were generated with either concentration of biotin for total anti-HAV (65/65). Likewise, biotin caused no false-positive IgM anti-HAV results (59/59) with either concentration of biotin; however, 6.7% false negativity was found for IgM anti-HAV when samples were spiked with 1200 ng/mL of biotin. Conversely, 100% false positivity (30/30) was produced by biotin interference in total anti-HAV negative specimens with both concentrations of biotin. False negativity rate was 87.5% in IgM anti-HBc positive samples when biotin levels were at 1200 ng/mL. These data show that individuals taking biotin-containing supplements may test false-positive in some serologic assays using streptavidin-biotin chemistries. Further studies are warranted to determine the extent of biotin interference resulting in false-positive and negative results and their impact, if any, on surveillance and diagnostic settings.

Highlights

- Exogenous biotin can interfere with some markers of viral hepatitis on the Ortho VITROS platform.

- Depending on the assay, either false positives or false negatives may be observed in the presence of exogenous biotin.

- The results of the serologic assays that use streptavidin-biotin chemistry need to be interpreted with caution.

Abbreviations

-

- Anti-HAV

-

- antibodies to hepatitis A virus

-

- Anti-HBc

-

- antibodies to hepatitis B virus core antigen

-

- HAV

-

- hepatitis A virus

-

- HBV

-

- hepatitis B virus

-

- IgG

-

- Immunoglobulin G

-

- IgM

-

- Immunoglobulin M

-

- PBS

-

- phosphate buffered saline

1 INTRODUCTION

Biotin is water-soluble vitamin B involved in a range of metabolic processes related to utilization of fats, carbohydrates, and amino acids.1 Over-the-counter biotin intake has gained in popularity due to its purported ability to improve the health and appearance of hair, skin, and nails. While an adequate daily dose is 30 to 70 µg/day for adults,2 many of the supplements available may contain 1 to 20 mg of biotin per tablet and 30 to 300 µg are typically found in multivitamins. Biotin intake is also recommended by some clinicians as part of the treatment for mitochondrial diseases, certain inborn metabolic disorders, and neurological defects, with recommended dosages up to 300 mg/day2. The Food and Drug Administration (FDA) recommends testing interference of up to 1200 ng/mL of biotin in serum in biotin-streptavidin-based immunoassays since this level can be found in individuals who consume 300 mg/day of biotin as a nutritional supplement.3

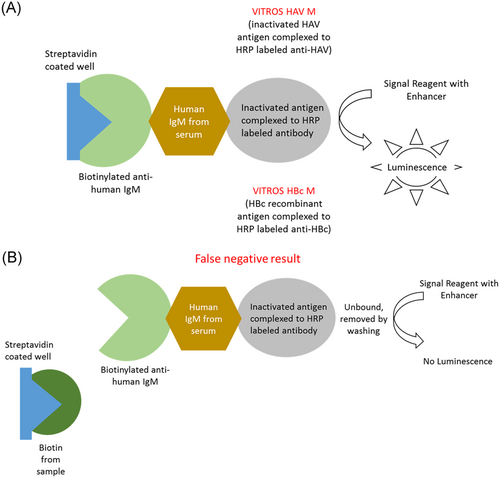

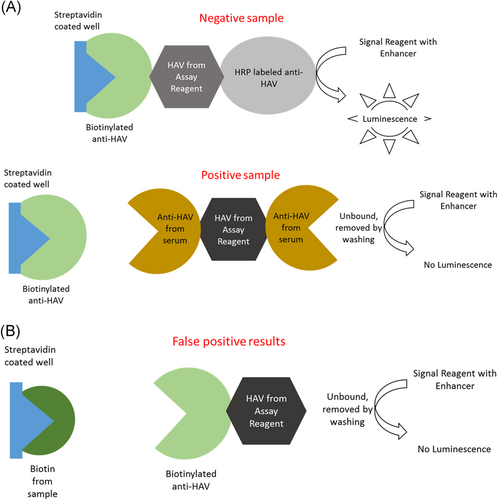

Biotin half-life is 1 hour and 50 minutes, and its concentration peaks in human serum 1 hour after oral intake.2 Despite the short half-life of biotin, one study found that 7.4% of patients seen in the emergency department were found to have biotin concentrations high enough to cause interference in assays using biotin-streptavidin.4 The amount of peak biotin depends on oral intake of the vitamin. For example, people with just dietary intake of biotin peak at 0.1 to 0.8 ng/mL, while people who take 5 to 10 mg/day peak at around 30 ng/mL, and people who take 300 mg peak at around 1200 ng/ml2. Orally taken biotin interferes with some diagnostic tests using biotin-streptavidin-based chemistry for detection of serological markers. A study found that about 59% of immunoassays used in the United States are based on the biotin-streptavidin chemistry.5 Biotin present in human serum may generate potential false-negative results in sandwich immunoassays and false-positive results in competitive immunoassays2 (Figures 1 and 2). There are only a few studies addressing the effect of low-level biotin intake on the results of the assays for detection of various viral hepatitis markers.6, 7 We investigated the effects of high levels of biotin on Immunoglobulin M (IgM) antibodies to hepatitis A virus (anti-HAV), total anti-HAV and IgM antibodies to hepatitis B virus core antigen (anti-HBc) tests, all of which use streptavidin-biotin chemistry, on the VITROS 3600 Immunodiagnostic Platform (Ortho Clinical Diagnostics, Raritan, NJ).

2 MATERIALS AND METHODS

De-identified human plasma samples from a plasma donation center rejected for antibody reactivity to human immunodeficiency virus (HIV), parvovirus, or hepatitis B surface antigen (HBsAg), and/or nucleic acid positivity for HIV, hepatitis B virus, or hepatitis C virus were used for this study and characterized for all markers of hepatitis in the Hepatitis Diagnostic Reference Laboratory at CDC using Clinical Laboratory Improvement Amendments approved tests. From these samples, a panel of positive and negative samples for IgM anti-HAV, total anti-HAV, and anti-HBc was developed based on the results from the antibody testing using Ortho Clinical (Raritan, NJ) FDA approved immunoassays. The first aliquot was spiked with phosphate buffered saline (PBS, 10% vol/vol), the second with 300 ng/mL biotin in PBS (10% vol/vol), and the third with 1200 ng/mL biotin in PBS (10% vol/vol). The specimens were tested on the VITROS 3600 Immunodiagnostic Platform according to the manufacturer's instructions for each marker. As a control, we determined the effect of the same biotin concentrations on the results of the HBsAg assay, which does not utilize streptavidin-biotin detection chemistry, on the same immunoanalyzer.

3 RESULTS

For IgM anti-HAV, a serological sandwich assay, 1200 ng/mL biotin concentration in the specimen generated 6.7% false negatives (2/30), while no false positives were observed (0/30). Among the specimens spiked with 300 ng/mL of biotin, 3% false negatives (1/30) were detected, and no false positives (Table 1). For total anti-HAV, a competitive serological assay, test results in specimens spiked with 1200 ng/mL biotin were 100% false-positive (30/30), while no false negatives were observed (0/30). Identical results were achieved with 300 ng/mL of biotin (Table 1). For IgM anti-HBc, an antibody capture assay, the addition of 1200 ng/mL biotin generated 87.5% false negatives (7/8). While no false positives (0/42) were observed due to biotin intake with 300 ng/mL of biotin spike, there were 25% false negatives (2/8) (Table 1). For the control HBsAg assay, which does not involve biotin-streptavidin chemistry, biotin spike at either concentration had no effect on the assay results (Table 1).

| Marker | Pos | Neg | Biotin concentration | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0 ng/mL | 300 ng/mL | 1200 ng/mL | ||||||

| FP | FN | FP | FN | FP | FN | |||

| HBsAg | 26 | 27 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| IgM anti-HBc | 8 | 42 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 2 (25%) | 0 | 7 (87.5%) |

| IgM anti-HAV | 30 | 59 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 (3%) | 0 | 2 (6.7%) |

| Total anti-HAV | 57 | 30 | 0 | 0 | 30 (100%) | 0 | 30 (100%) | 0 |

- Abbreviations: FN, false-negative; FP, false-positive; HBsAg, hepatitis B virus surface antigen; no biotin chemistry; IgM anti-HAV, Immunoglobulin M antibodies to hepatitis A virus; IgM anti-HBc, Immunoglobulin M antibodies to hepatitis B core antigen; Total anti-HAV, total antibodies to hepatitis A virus.

4 DISCUSSION

Biotin intake as a nutritional supplement has been shown to have no effect on the results of the assays for detection of various viral hepatitis markers.6, 7 The FDA recommends testing the effects of up to 1200 ng/mL biotin on the performance of serologic markers that utilize biotin-streptavidin chemistry. We demonstrated the effect of this high concentration on three viral hepatitis markers on the Ortho Clinical Diagnostics Platform VITROS 3600. Ortho Clinical Diagnostics does not provide biotin interference threshold for their assays. A statement is provided in the product insert limitations section that biotin level in serum may remain elevated up to 24hours after either oral intake or infusion.8, 9 Our data show that three of the assays for hepatitis markers used on the VITROS 3600 which utilize streptavidin-biotin detection chemistry were partially affected by high levels of biotin; biotin levels lower than FDA suggests may interfere with tests producing both false positives or false negatives results, dependent on assay. High concentrations of biotin affected three different streptavidin-biotin chemistry dependent assays differently. Whether biotin was present in the samples before testing does not affect the results of this study since we previously determined antibody response in these specimens before biotin spike; discordant results from the same sample was only obtained after biotin was spiked/introduced into the sample before retest.

The strongest effect of biotin was seen in total anti-HAV assay generating false-positive results, suggesting that people who take large amounts of biotin would be deemed immune to HAV infection, when they are potentially susceptible. Competitive assays are particularly susceptible to excess biotin; analyte concentration is inversely proportional to signal intensity. High amounts of biotin in serum will compete with the biotinylated antibody for the biotin-binding sites on the microplate, decreasing the intensity of the signal, and resulting in false positivity. In addition, free biotin from the specimen may have higher affinity for well-bound streptavidin than the biotinylated anti-HAV complex from the reagent kit. The other two assays in this study, IgM anti-HAV and IgM anti-HBc, are based on capture by human IgM; subsequent steps allow for target-specific detection. In this case, the free biotin binds the streptavidin blocking the antibody from binding and producing a signal leading to false negativity. Sandwich assays have a much larger dynamic range than competitive assays, therefore may be less affected by the excess biotin resulting in lower percent of false negatives.

With biotin gaining popularity as a nutritional supplement, high levels of biotin that can significantly affect serological assays for hepatitis viruses should be assessed by clinicians ordering serological tests. Data on biotin levels in different populations are not widely available, and there is a need for studies to answer this question. Because of the potential biotin interference, the results of the serologic assays that use streptavidin-biotin chemistry need to be interpreted with caution for those individuals who are known to take biotin.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

The findings and conclusions in this paper are those of the authors and do not necessarily represent the views of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Use of trade names is for identification only and does not imply endorsement by the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, the Public Health Service, or the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.