Dynamics of HCV RNA levels during acute hepatitis C virus infection

Correspondence to: Behzad Hajarizadeh, The Kirby Institute, Wallace Wurth Building, UNSW Australia, Sydney NSW 2052, Australia.

E-mail: [email protected]

Abstract

Understanding viral dynamics during acute hepatitis C virus (HCV) infection can provide important insights into immunopathogenesis and guide early treatment. The aim of this study was to investigate the dynamics of HCV RNA and alanine transaminase (ALT) levels during recent HCV infection in the Australian Trial in Acute Hepatitis C (ATAHC). ATAHC was a prospective study of the natural history of recently acquired HCV infection. Longitudinal HCV RNA and ALT levels were compared among individuals with persistent infection and spontaneous clearance. Among those with HCV persistence (n = 104) and HCV clearance (n = 30), median HCV RNA (5.2 vs. 4.1 log IU/ml, respectively) and ALT levels (779 vs. 1,765 IU/L, respectively) were high during month two following infection, and then declined during months three and four in both groups. Among those with HCV persistence, median HCV RNA was 2.9 log IU/ml during months four, increased to 5.5 log IU/ml during month five, and remained subsequently relatively stable. Among those with HCV clearance, median HCV RNA was undetectable by month five. Median HCV RNA levels were comparable between individuals with HCV persistence and HCV clearance during month three following infection (3.2 vs. 3.5 log IU/ml, respectively; P = 0.935), but markedly different during month five (5.5 vs. 1.0 log IU/ml, respectively; P < 0.001). In conclusion, dynamics of HCV RNA levels in those with HCV clearance and HCV persistence diverged between months three and five following infection, with the latter time-point being potentially useful for commencing early treatment. J. Med. Virol. 86: 1722–1729, 2014. © 2014 Wiley Periodicals, Inc.

INTRODUCTION

Acute hepatitis C virus (HCV) infection is characterized by the appearance of virus in the blood within 2–14 days of exposure, increases in the levels of liver-associated serum enzymes particularly alanine transaminase (ALT), and gradual appearance of HCV-specific antibodies (anti-HCV antibody) within 30–60 days of exposure (reviewed in [Grebely et al., 2011; Hajarizadeh et al., 2013]).

Acute HCV infection is followed by spontaneous clearance, defined by repeated undetectable HCV RNA in the blood, in around 25% of individuals [Micallef et al., 2006; Grebely et al., 2014]; the remaining 75% progress to chronic HCV infection with potential consequences of cirrhosis, liver failure, and hepatocellular carcinoma.

Understanding the patterns of change (dynamics) in HCV RNA and ALT levels during progression from acute to chronic HCV infection can provide important insights into immunopathogenesis. It may also have clinical utility in predicting spontaneous HCV clearance and hence guide in better timing for early treatment.

The dynamics of HCV RNA levels in early acute HCV (i.e., from exposure to seroconversion) have been characterized as occurring in three phases: a pre-ramp-up phase with intermittent low-level HCV RNA (from exposure to initial quantifiable HCV RNA); a ramp-up phase with exponential increase in HCV RNA levels (8–10 days); and a high-titre viremic plateau phase (45–68 days) [Glynn et al., 2005]. However, further data are needed to improve understanding of HCV RNA dynamics during progression from acute to chronic HCV infection. In addition, several studies investigating HCV RNA dynamics in acute HCV have enrolled blood product recipients [Barrera et al., 1995; Farci et al., 2000], frequent blood donors [Nübling et al., 2002; Glynn et al., 2005], haemodialysis patients [Lavillette et al., 2005; Weseslindtner et al., 2009], or health care workers [Thimme et al., 2001] where the date of exposure can be determined. However, these studies are generally limited by small sample sizes and are not representative of the most common form of HCV acquisition in developed countries (i.e., people who inject drugs). Individuals acquiring HCV through injecting drug differ in age, underlying health status, and generally less precise estimation of time of exposure.

This study sought to assess the dynamics of HCV RNA and ALT levels in recent HCV infection, with a particular focus on the transitional period during progression from acute to chronic infection, among individuals predominantly infected through injecting drug use.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Study Design and Participants

The Australian Trial in Acute Hepatitis C (ATAHC) was a prospective study of the natural history and treatment of recently acquired HCV infection. The ATAHC study design has been described previously in detail [Dore et al., 2010]. Individuals diagnosed with recent HCV infection (defined below) were recruited from June 2004 through November 2007. Recent infection with either acute or early chronic HCV infection was defined by the following eligibility criteria:

- Acute clinical hepatitis C infection, defined as symptomatic seroconversion illness or ALT level greater than 10 times the upper limit of normal (ULN, >400 IU/L) with exclusion of other causes of acute hepatitis, at most 12 months before the initial positive anti-HCV antibody; or

- Asymptomatic hepatitis C infection with seroconversion, defined by a negative anti-HCV antibody within the 2 years prior to the initial positive anti-HCV antibody.

Participants were followed from enrolment (screening) for up to 12 weeks (baseline) to allow for spontaneous clearance, and if HCV RNA remained detectable at the baseline visit, they were offered treatment. Participants unwilling to undergo treatment and those with undetectable HCV RNA at screening or baseline continued to be followed. Participants were followed up from baseline at 12 weekly intervals for up to 144 weeks.

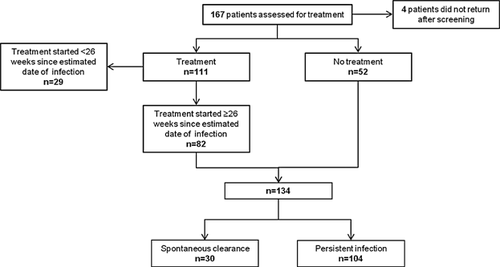

In the current analysis, all longitudinal HCV RNA and ALT measurements for untreated individuals (n = 52) were used to assess the dynamics of HCV RNA and ALT levels. Among treated individuals (n = 111), those with an estimated duration of infection <26 weeks on treatment commencement (n = 29) were excluded to reduce misclassification bias due to uncertainty around subsequent spontaneous clearance without treatment. Twenty-six weeks (6 months) was chosen as the cut-off given it has been shown that the large majority of individuals will spontaneously clear infection during the first 6 months following infection [Page et al., 2009]. Individuals treated for HCV with an estimated duration of infection ≥26 weeks were included, but only HCV RNA and ALT data up to and including the date of treatment commencement (baseline) were included in the analysis. A total number of 134 individuals were included in analysis including 52 untreated and 82 treated individuals (Fig. 1).

All study participants provided written informed consent. The study protocol was approved by St. Vincent's Hospital, Sydney Human Research Ethics Committee (primary study committee) as well as through local ethics committees at all study sites. The study was registered with clinicaltrials.gov registry (NCT00192569).

Study Definitions

Estimated date of infection

For individuals with acute clinical infection, the estimated date of infection was calculated as 6 weeks prior to onset of the seroconversion illness if present, or 6 weeks prior to the first ALT reading above 400 IU/L. For asymptomatic infection the estimated date of infection was calculated as the mid-point between the last negative anti-HCV antibody and the first positive anti-HCV antibody test result. For individuals who were anti-HCV antibody negative and HCV RNA positive at screening, the estimated date of infection was designated to be 6 weeks prior to screening.

Spontaneous HCV clearance

Participants with at least two undetectable qualitative HCV RNA tests (<10 IU/ml) ≥4 weeks apart following HCV infection detection.

Detection and Quantitation of HCV RNA

HCV RNA assessments were performed at all scheduled study visits, initially with a qualitative HCV RNA assay (TMA assay, Versant, Bayer, Pymble NSW, Australia; lower limit of detection 10 IU/ml) and if detectable repeated on a quantitative assay (Versant HCV RNA 3.0 Bayer, Pymble NSW, Australia; lower limit of detection 615 IU/ml). HCV genotyping using a commercial assay (Versant LiPa2, Bayer, Pymble NSW, Australia) was performed on all individuals with detectable HCV RNA at screening. Additional HCV genotyping using sequencing methods were also performed on longitudinal samples as described previously [Pham et al., 2010]. Briefly, RNA was extracted from 140 µl of sera using the QIAmp Viral RNA extraction kit (Qiagen, Hilden, Germany). The E1/HVR1 region encoding the last 171 basepairs (bp) of Core, E1, and the HVR-1 of E2 (840 bp, nucleotides 744–1,583, with reference to HCV strain H77, GenBank accession number AF009606) was amplified by a real-time nRT-PCR using reagents and reaction conditions as described [Pham et al., 2010].

Statistical Analyses

To evaluate the dynamics of HCV RNA and ALT levels during acute HCV infection, longitudinal HCV RNA and ALT levels were indexed by time since the estimated date of infection for all individuals. Population-average curves describing HCV RNA and ALT dynamics were constructed using longitudinal HCV RNA and ALT measurements. The median HCV RNA levels (log IU/ml) and ALT levels (IU/L) among all individuals were calculated in monthly intervals since estimated date of infection. To calculate monthly medians of HCV RNA and ALT, all individual measurements recorded during each 1-month intervals were included. All analyses were performed using Stata version 12.0 (Stata, College Station, TX) and graphs were generated using GraphPad Prism (GraphPad Software, La Jolla, CA).

RESULTS

A total of 134 individuals with recent HCV infection were included in this study among whom 82 received HCV treatment and 52 were untreated (Fig. 1). The background and baseline characteristics of included participants are summarized in Table I.

| Persistent infection (n = 104) | Spontaneous clearance (n = 30) | |

|---|---|---|

| Male sex, n (%) | 71 (68) | 20 (67) |

| Median age, years (IQR*) | 33 (24, 41) | 34 (26, 37) |

| Caucasian ethnicity, n (%) | 95 (91) | 28 (93) |

| Median estimated duration of infection at screening, week (IQR*) | 29 (21, 45) | 23 (20, 31) |

| Presentation of recent HCV, n (%) | ||

| Acute clinical (symptomatic) | 39 (38) | 14 (47) |

| Acute clinical (ALT >400 IU/L) | 14 (13) | 5 (17) |

| Asymptomatic seroconversion | 51 (49) | 11 (37) |

| Mode of HCV acquisition, n (%) | ||

| Injecting drug use | 78 (75) | 23 (77) |

| Sexual intercourse | 18 (17) | 3 (10) |

| Other | 8 (8) | 4 (13) |

| HCV genotype, n (%) | ||

| Genotype 1 | 49 (47) | 6 (20) |

| Genotype 2 | 4 (4) | 0 (0) |

| Genotype 3 | 46 (44) | 5 (17) |

| Genotype 4 | 1 (1) | 0 (0) |

| Not available | 4 (4) | 19 (63) |

| HIV infection, n (%) | 29 (28) | 7 (23) |

| IFNL3 genotype, n (%) | ||

| rs8099917 | ||

| GG | 5 (5) | 0 (0) |

| GT | 39 (37) | 4 (13) |

| TT | 56 (54) | 25 (83) |

| Not available | 4 (4) | 1 (3) |

| rs12979860 | ||

| CC | 49 (47) | 19 (63) |

| CT | 40 (38) | 9 (30) |

| TT | 12 (12) | 1 (3) |

| Not available | 3 (3) | 1 (3) |

- * IQR, inter-quartile range.

Dynamics of HCV RNA and ALT Levels

Spontaneous HCV clearance was observed in 30 individuals, while 104 individuals had persistent HCV infection. Among those with spontaneous clearance (n = 30), 18 individuals had undetectable HCV RNA at screening (indicative of spontaneous clearance prior to enrolment) and 12 individuals demonstrated spontaneous clearance during follow-up.

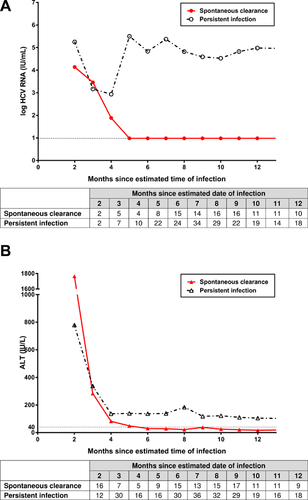

The dynamics of HCV RNA and ALT levels among individuals are illustrated in Figure 2 by HCV infection outcome. Median HCV RNA levels at month two following infection was 5.2 log IU/ml among those with persistent infection and was 4.1 log IU/ml among those with subsequent spontaneous clearance. Subsequent HCV RNA declines were seen in both groups, with similar median levels during month three in those with persistent infection (3.2 log IU/ml; inter-quartile range [IQR]: 2.8, 5.0) and spontaneous clearance (3.5 log IU/ml; IQR: 2.9, 5.0; P = 0.935). However, the pattern of median HCV RNA levels initiated to diverge between the two groups from month three to four: a slight decline to 2.9 log IU/ml (IQR: 2.8, 6.6) in those with persistent infection compared with a marked decline to 1.9 log IU/ml (IQR: 1.0, 3.1) in those with spontaneous clearance (P = 0.219 for comparison of month four levels). The divergence in median HCV RNA levels was accentuated from month four to five: a marked re-increase to 5.5 log IU/ml (IQR: 2.8, 6.4) in those with persistent infection contrasting with continued decline to undetectable level (IQR: 1.0, 2.8; P < 0.001 for comparison of month five levels; Fig. 2A).

High levels of ALT were observed at month two following infection among individuals with persistent infection (779 IU/L; IQR: 557, 1,624) and spontaneous clearance (1,765 IU/L; IQR: 496, 2,373; P = 0.239) followed by sharp declines by months four and five following infection. The median ALT decline was greater in those with spontaneous clearance, and remained within the normal range from month six. In contrast, median ALT levels in those with persistent infection remained elevated throughout follow-up (Fig. 2B).

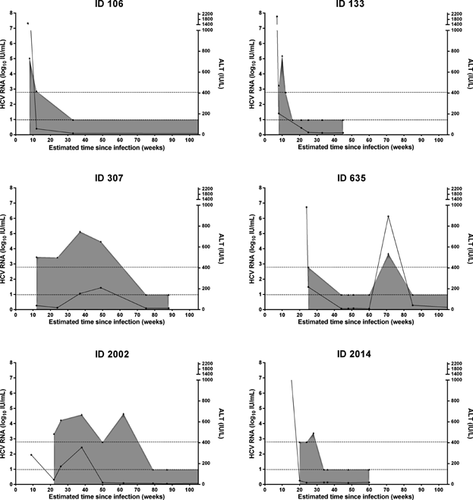

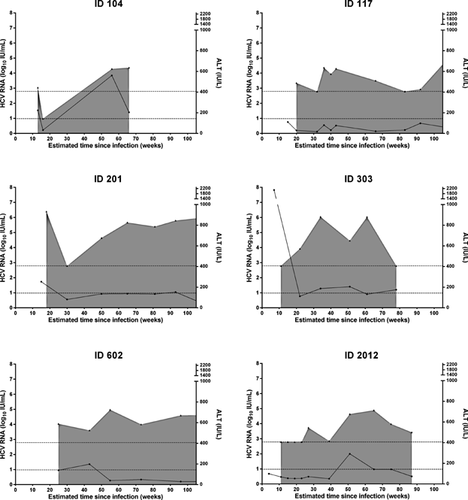

Although the patterns of the median HCV RNA and ALT are clearly distinct between the groups with persistent infection and spontaneous clearance (Fig. 2), there was considerable heterogeneity among individual patterns (Figures 3 and 4). For instance, among individuals with spontaneous clearance, participant ID 307 had increasing HCV RNA levels up to 9 months following infection but cleared infection eventually between month 12 and 18. Participant ID 635 showed spontaneous clearance with four undetectable HCV RNA assessments followed by HCV RNA recurrence 28 weeks after clearance (Fig. 3). Sequencing of samples taken at enrolment and subsequent detectable HCV RNA identified HCV re-infection (recurrence with heterologous strain) in this participant. Of interest, participant ID 635 had spontaneous clearance of re-infection following a single detectable HCV RNA assessment. Among those with persistent infection, participant ID 117 had two episodes of declining HCV RNA levels between months 5–8 and months 11–22 following infection, but both episodes were followed by a rebound in HCV RNA levels and progression to chronic infection. Participant ID 104 had one undetectable HCV RNA followed by HCV RNA recurrence 40 weeks after the intermittent undetectable HCV RNA (Fig. 4). Sequencing of samples taken at enrolment and subsequent detectable HCV RNA identified HCV RNA intercalation (recurrence with homologous strain) in this participant.

DISCUSSION

This prospective study characterized the dynamics of HCV RNA and ALT levels among individuals with recent HCV infection and indicated that median HCV RNA levels among those with subsequent spontaneous clearance and persistent infection diverged between months three and five following infection onset. In those with spontaneous clearance, a continuous decline in HCV RNA was observed between months two and five following infection as compared to an initial decline followed by an increase in HCV RNA among those with persistent infection. HCV RNA changes during this period may be useful in guiding early therapeutic intervention. However, the degree of heterogeneity in HCV RNA and ALT patterns among individuals with persistent infection and spontaneous clearance makes these inadequate as sole measures to guide therapy. Other factors, including polymorphism in the interferon lambda 3 (IFNL3; formerly called interleukin 28) gene region [Grebely et al., 2010; Grebely et al., 2011; Grebely et al., 2014] or the newly discovered interferon lambda 4 (IFNL4) gene region [Prokunina-Olsson et al., 2013], should be considered in therapeutic decision-making.

The virologic patterns demonstrated in this study, with evidence of enhanced virological control between month two and three in individuals with persistent infection and spontaneous clearance, and subsequent loss of control between month three and four in those with persistent infection, is consistent with a recent study that utilized next generation sequencing to evaluate early HCV viral evolution. In that study reductions in both HCV RNA levels and genetic diversity were identified within 100 days of infection (a “bottleneck” effect) irrespective of infection outcome, with subsequent increased HCV RNA levels and diversity in those with persistent infection [Bull et al., 2011]. Early virologic patterns have been evaluated previously as predictors of outcome. Thomson et al. reported that spontaneous clearance was associated with a 2.2 log drop in HCV RNA levels within 100 days following infection in a large cohort of individuals with HIV co-infection [Thomson et al., 2011].

Despite clearly divergent overall patterns in HCV RNA levels between those with persistent infection and spontaneous clearance, considerable heterogeneity was documented among individual cases. This variance included cases with relatively high HCV RNA levels during acute HCV infection, with spontaneous clearance beyond 6 months infection, and cases with large HCV RNA declines during acute HCV infection, without subsequent spontaneous clearance. Fluctuation in HCV RNA levels has been reported as a hallmark of the viral dynamics in the early stages of HCV infection, and was described by some investigators as a “yo-yo” pattern [Aberle et al., 2006; Smith et al., 2010]. Various studies have reported that a wide range (37–86%) of individuals with acute HCV experienced significant viral load fluctuations (generally defined as ≥1 log HCV RNA change) [McGovern et al., 2009; Smith et al., 2010; Loomba et al., 2011; Thomson et al., 2011]. Larger datasets of individuals with acute HCV infection are required to more fully characterize early virologic patterns, and to evaluate predictive models for spontaneous clearance. Such models may incorporate virologic features (HCV RNA level [Liu et al., 2012], early viral load decline [Thomson et al., 2011], and HCV genotype [Grebely et al., 2014]), demographic features (age [Zhang et al., 2006; Garten et al., 2008], gender [Micallef et al., 2006; Page et al., 2009; Grebely et al., 2014]), and host genetic (IFNL3 [Grebely et al., 2010; Tillmann et al., 2010; Grebely et al., 2014], IFNL4 [Prokunina-Olsson et al., 2013], HLA DQB1*03:01 [Duggal et al., 2013]) and biomarkers (IP-10 [Grebely et al., 2013a]), as all these factors have been associated with spontaneous clearance.

This study has some limitations. Most of the individuals with detectable HCV RNA at enrolment had an estimated duration of infection more than 1 month hence the very early dynamics of the HCV RNA levels were therefore missed. Further, estimated date of infection might not have been accurate for some individuals, particularly for asymptomatic individuals with a long period between their last HCV negative and first HCV positive tests. Although the number of individuals is relatively large for an acute HCV infection study, many individuals had relatively infrequent HCV RNA assessments. Thus, some monthly time-points had small numbers of HCV RNA measurements available. As mentioned previously, larger sample populations combining individuals from acute HCV cohorts is required to further characterize early viral dynamics. The International Collaboration of Incident hepatitis C in Injecting drug user Cohorts (InC3) has been established recently, with nine acute HCV cohorts (including ATAHC). Epidemiological studies are underway through InC3 to meet this objective [Grebely et al., 2013b].

In conclusion, the current data suggested that HCV RNA dynamics in those with HCV clearance and HCV persistence diverged between months three and five following infection, with the latter time-point being potentially useful for timing of early therapeutic intervention.