Epstein-Barr virus viral load and serology in childhood non-Hodgkin's lymphoma and chronic inflammatory conditions in Uganda: Implications for disease risk and characteristics

Abstract

Epstein-Barr virus (EBV) has been linked to malignancies and chronic inflammatory conditions. In this study, EBV detection was compared in children with non-Hodgkin's lymphoma and children with chronic inflammatory conditions, using samples and data from a case-control study carried out at the Mulago National Referral Hospital between 2004 and 2008. EBV viral load was measured in saliva, whole blood and white blood cells by real-time PCR. Serological values for IgG-VCA, EBNA1, and EAd-IgG were compared in non-Hodgkin's lymphoma and chronic inflammatory conditions; and in Burkitt's lymphoma and other subtypes of non-Hodgkin's lymphoma. Odds ratios (ORs) and corresponding 95% confidence intervals (CIs) were calculated. Of the 127 children included (87 males and 40 females; median age 7 years, range 2–17), 96 had non-Hodgkin's lymphoma (46 Burkitt's lymphoma and 50 other non-Hodgkin's lymphoma), 31 had chronic inflammatory conditions, and only 10% were HIV-positive. The most common clinical presentations for all disease categories considered were fever, night sweats, and weight loss. EBV viral load in whole blood was elevated in Burkitt's lymphoma compared to other non-Hodgkin's lymphoma (OR 6.67, 95% CI 1.32, 33.69; P-value = 0.04), but EBV viral loads in saliva and white blood cells were not different in any of the disease categories considered. A significant difference in EAd-IgG was observed when non-Hodgkin's lymphoma was compared with chronic inflammatory conditions (OR 0.19, 95% CI 0.07, 0.51; P-value = 0.001). When compared to chronic inflammatory conditions, EBV viral load was elevated in Burkitt's lymphoma, and EA IgG was higher in non-Hodgkin's lymphoma. This study supports an association between virological and serological markers of EBV and childhood non-Hodgkin's lymphoma, irrespective of subtype, in Uganda. J. Med. Virol. 86: 1796–1803, 2014. © 2014 Wiley Periodicals, Inc.

INTRODUCTION

Epstein-Barr virus (EBV) is a ubiquitous virus with global infection rates of over 90% [Shah and Young, 2009]. Despite this large number, only a small proportion of the world population develops EBV-related disease. Acute manifestations of EBV infection, such as infectious mononucleosis, are also few and far between. The most well-known complication of EBV infection is the development of malignant diseases, such as Hodgkin's lymphoma, various types of non-Hodgkin's lymphoma (e.g., Burkitt's lymphoma), post-transplant, and AIDS-related lymphoproliferative disorders, diffuse large B-cell lymphoma and Natural Killer/T-cell lymphoma, nasopharyngeal carcinoma, gastric adenocarcinoma, and leiomyosarcoma and leiomyoma, which occur mostly in HIV/AIDS patients. The prevalence of these malignancies differs by age, geographical location, and socioeconomic and environmental co-factors [Kutok and Wang, 2006].

In developing countries in sub-Saharan Africa, EBV-related malignancies occur at a fairly early age, which might be due to infection with EBV early in life. More than 80% of children in sub-Saharan Africa become infected with EBV between 2 and 4 years of age, but they are generally capable of mounting appropriate anti-EBV immune responses [Piriou et al., 2012]. Poor socioeconomic conditions, malnutrition, co-infections, poor hygiene, and overcrowding are risk factors for early EBV infection, and are associated with aberrant anti-EBV immune responses [Sumba et al., 2010]. This may explain the demographic differences between EBV-related malignancies in developed and developing countries in Asia and sub-Saharan Africa.

Differences in the disease pattern of EBV-related malignancies in developed and developing countries might also exist. Indeed, in developed countries these malignancies occur more often in adults, whereas in developing countries in Africa these malignancies tend to occur mainly in children, although there are exceptions [Adham et al., 2012]. The most common EBV-related malignancy in sub-Saharan Africa is endemic Burkitt's lymphoma [Parkin et al., 2000]. The most common clinical characteristics of endemic Burkitt's lymphoma in Africa are uncommon in Asia and other parts of the developing world, including Latin America. Moreover, in Asia and other parts of the developing world these characteristics are not always associated with EBV infection [Kim et al., 2005]. Instead, these peculiar characteristics are most likely due to differences in co-factors, such as malaria, general health status, immune status, and age [Carpenter et al., 2008]. The presence of EBV DNA has been linked to the development of lymphoid malignancies in children [Moormann et al., 2005], whereas levels of antibodies against distinct EBV antigen complexes reflect either quiescent or reactive EBV persistence.

Given the growing list of EBV-related malignancies and chronic inflammatory conditions, it is important to review the role of EBV infection in childhood non-Hodgkin's lymphoma and chronic inflammatory conditions. Many studies have focused on understanding the precise role of EBV in the causation of endemic Burkitt's lymphoma. Given the early onset of EBV infection and the multiple factors at play in children, the juvenile population is best suited to provide clues about this unique association. Therefore, the aim of this study was to understand the relationship between childhood non-Hodgkin's lymphoma and chronic inflammatory conditions and biological markers of EBV infection. To this end, clinical characteristics, EBV viral load in blood and saliva, and antibody levels against distinct viral antigen complexes were determined and compared in children with non-Hodgkin's lymphoma and those with chronic inflammatory conditions. The hypothesis is that aberrant EBV activity, such as elevated EBV viral load and increased antibody titers to distinct EBV antigens, might be related to disease type and characteristics.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

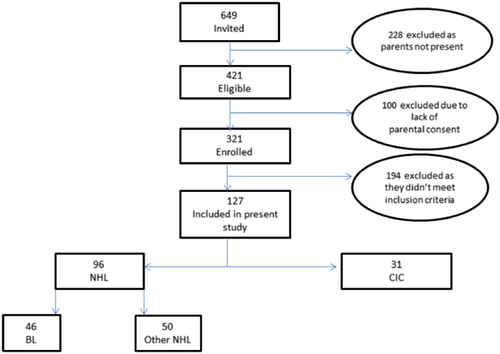

Data and samples were used from a case-control study of childhood non-Hodgkin's lymphoma conducted between 2004 and 2008 at the Mulago National Referral Hospital, Kampala, Uganda. The study site, participants and referral mechanism for childhood cancer in Uganda have been described previously [Orem et al., 2011, 2012]. Briefly, in the aforementioned case-control study, children with suspected malignancies and chronic inflammatory conditions who sought care at the Mulago National Referral Hospital were identified, and informed consent was sought from their parents or guardians. Assent was obtained from children over 9 years of age before study enrollment. Children then underwent clinical examination, at which time detailed clinical and demographic information was collected by questionnaire. Children without clinical or demographic data were excluded (Fig. 1).

Diagnostic procedures used in the case-control study have been published previously [Orem et al., 2012]. Briefly, children with a clinical diagnosis of non-Hodgkin's lymphoma at the Mulago National Referral Hospital were referred to the Uganda Cancer Institute in Kampala for specialized management. If the clinical diagnosis of non-Hodgkin's lymphoma was confirmed at the Uganda Cancer Institute, the patient was considered a suspected “non-Hodgkin's lymphoma case.” Children with other malignancies and children with chronic inflammatory conditions were considered suspected “tumor controls” and suspected “non-tumor controls,” respectively. Cases and controls were not matched for any patient characteristics in the case-control study. In the absence of a standard definition of chronic inflammatory conditions, in the present study, it was defined as a condition that had been reported by parents, was noticed at least 2 months prior to study enrollment, and led to the collection of a tissue sample for diagnosis. These diagnoses included musculoskeletal masses, non-specific lymphadenitis, chronic allergic conditions, vasculitis, and other glandular swelling, among others.

Fresh tissue samples, saliva samples and blood samples were collected from all children. Tissue samples were divided into two specimens: one was stored at −80°C and one was embedded in paraffin and sent to the Department of Pathology, Makerere University College of Health Sciences, Kampala, Uganda, for histological diagnosis. Saliva samples were collected using the ORACOL saliva test kit (Malvern Medical Developments, Worcester, UK) as per the manufacturer's instructions. Saliva samples and 1 ml of whole blood and WBCs were frozen and stored at −80°C. Children that did not have all three biological samples available were excluded from this analysis.

Fresh-frozen tissue samples, paraffin-embedded tissue samples, original pathological slides, saliva samples and samples of whole blood and WBCs that were judged to be of sufficient quality and quantity were then shipped to the Department of Pathology at the VU University Medical Center, Amsterdam, the Netherlands, for review. This laboratory is an academic center of excellence for cancer pathology, and highly specialized in EBV- and other virus-related cancers. Morphological examination of the submitted slides was performed in the Netherlands by pathologists with expertise in lymphoma. Pathologists in the Netherlands were blinded to clinical and pathological diagnoses assigned in Uganda. Reporting criteria was based on the presence of non-Hodgkin's lymphoma (i.e., Burkitt's lymphoma, or other subtypes of non-Hodgkin's lymphoma, referred to hereafter as “other non-Hodgkin's lymphoma”), the presence of other tumors, or the presence of other processes with no tumor (e.g., specific infectious conditions such as tuberculosis). New histological slides were made in the Netherlands from paraffin-embedded tissue samples received from Uganda, that is, 5–10 separate parallel sections were cut for hematoxylin and eosin staining. EBV-encoded small RNA (EBER) by RNA in situ hybridization (EBER-RISH), plus CD10, bcl2 and control staining, including pan-B-cell antigen (CD19), pan-T-cell antigen (CD3), and cytokeratin-18 was done, with all analyses performed using standardized procedures. Burkitt's lymphoma was defined as CD10+/bcl2−/CD19+/CD3−/CK18− [Orem et al., 2012]. Diagnoses and test results in the present report reflect laboratory results from the Netherlands.

Ethical approval for the study was obtained from the Makerere University College of Health Sciences Ethical Committee, Kampala, Uganda, and the Uganda National Council for Science and Technology.

EBV Testing

EBV viral load was measured by quantitative real-time PCR in saliva, whole blood and WBCs. Saliva samples were dissolved in 4 ml NucliSens lysis buffer (bioMérieux, Boxtel, the Netherlands), and the absorption pad extracted. Total nucleic acids (DNA and RNA) were obtained by silica-based isolation and quantified by PCR as described previously [Stevens et al., 2005]. EBV viral load cut-off levels and normal to elevated clinically relevant levels have been defined previously [Stevens et al., 2002]. EBV serology was performed by ELISA, which measured IgG antibodies against viral capsid antigen (VCA-p18 IgG), EBV nuclear antigen (EBNA1-IgG), and early antigen (EAd-IgG), as described previously [Meij et al., 1999; de Sanjosé et al., 2007; Piriou et al., 2009].

Serological results for HIV were obtained by ELISA (Abbott Diagnostics, Abbott Park, IL) and malaria was reported based on microscopy of Giemsa-stained thick-smears.

Statistical Methods

The clinical characteristics of study children were explored by calculating summary statistics for all non-Hodgkin's lymphoma, Burkitt's lymphoma, other non-Hodgkin's lymphoma and chronic inflammatory conditions. Initially, children with non-Hodgkin's lymphoma were compared to those with chronic inflammatory conditions. Then non-Hodgkin's lymphoma was divided into subtypes (Burkitt's lymphoma and other non-Hodgkin's lymphoma) and children with Burkitt's lymphoma were compared to those with other non-Hodgkin's lymphoma. EBV viral load in saliva, whole blood and WBCs was classified into three categories (high, intermediate, and low) and compared as mentioned above. The level of antibody titers was also classified into three categories (positive, normal, and elevated) and compared. To analyze the associations between type of disease and EBV viral load and serology, odds ratios (ORs) and associated two-sided 95% confidence intervals (CIs) were calculated by fitting ordinary logistic regression. SAS software version 9.3 was used for all calculations.

RESULTS

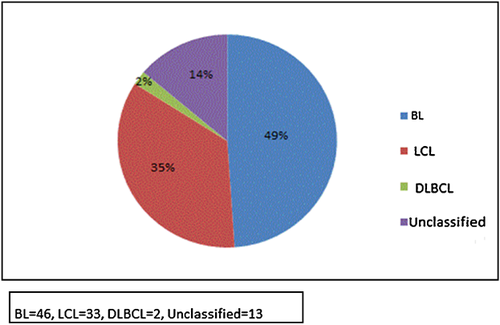

Out of 321 children enrolled in the original case-control study between 2004 and 2008, 194 did not meet the inclusion criteria for the present analysis, leaving 127 children (87 male children and 40 female children, median overall age 7 years, range 2–17) (Table I). Ninety-six children had non-Hodgkin's lymphoma (46 with Burkitt's lymphoma and 50 with other non-Hodgkin's lymphoma) (Fig. 2) and 31 had chronic inflammatory conditions.

| Characteristic | All NHL | BL | Other NHL (except BL) | CIC | P-value | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N = 96 | N = 46 | N = 50 | N = 31 | ||||||

| Frequency | % | Frequency | % | Frequency | % | Frequency | % | ||

| Gender | |||||||||

| Male | 68 | 70.8 | 33 | 71.7 | 35 | 70.0 | 19 | 61.3 | 0.375 |

| Female | 28 | 29.2 | 13 | 28.3 | 15 | 30.0 | 12 | 38.7 | |

| Age, years, median (IQR) | 7 (5) | 7 (5) | 7 (5) | 7 (5) | 0.876 | ||||

| Fever | |||||||||

| Yes | 75 | 83.3 | 39 | 88.6 | 36 | 78.3 | 25 | 80.7 | 0.785 |

| No | 15 | 16.7 | 5 | 11.4 | 10 | 21.7 | 6 | 19.4 | |

| Night sweats | |||||||||

| Yes | 63 | 70.0 | 34 | 73.9 | 29 | 58.0 | 23 | 74.2 | 0.819 |

| No | 27 | 30.0 | 10 | 21.7 | 17 | 34.0 | 8 | 25.8 | |

| Weight loss | |||||||||

| Yes | 54 | 60.0 | 29 | 65.9 | 25 | 54.3 | 22 | 71.0 | 0.389 |

| No | 36 | 40.0 | 15 | 34.1 | 21 | 45.7 | 9 | 29.0 | |

| Lympadenopathy | |||||||||

| Yes | 16 | 18.4 | 4 | 9.8 | 12 | 26.1 | 5 | 16.7 | 1.000 |

| No | 71 | 81.6 | 37 | 90.2 | 34 | 73.9 | 25 | 83.3 | |

| Facial swelling | |||||||||

| Yes | 37 | 41.1 | 20 | 45.4 | 17 | 37.0 | 15 | 48.4 | 0.532 |

| No | 53 | 58.9 | 24 | 54.6 | 29 | 63.0 | 16 | 51.6 | |

| Extra facial mass | |||||||||

| Yes | 39 | 43.3 | 17 | 38.6 | 22 | 47.8 | 12 | 38.7 | 0.680 |

| No | 51 | 56.7 | 27 | 61.4 | 24 | 52.2 | 19 | 61.3 | |

| Abdominal disease | |||||||||

| Yes | 33 | 36.7 | 15 | 34.1 | 18 | 39.1 | 9 | 29.0 | 0.516 |

| No | 57 | 63.3 | 29 | 65.9 | 28 | 60.9 | 22 | 71.0 | |

| Liver involvement | |||||||||

| Yes | 7 | 7.9 | 5 | 11.6 | 2 | 4.4 | 1 | 3.2 | 0.678 |

| No | 82 | 92.1 | 38 | 88.4 | 44 | 95.6 | 30 | 96.8 | |

| HIV Status | |||||||||

| Positive | 10 | 10.6 | 5 | 11.1 | 5 | 10.2 | 2 | 6.9 | 0.730 |

| Negative | 84 | 89.4 | 40 | 88.9 | 44 | 89.8 | 27 | 93.1 | |

| Malaria | |||||||||

| Yes | 51 | 100 | 25 | 100 | 26 | 100 | 16 | 100 | 1.000 |

| No | 0 | 0.0 | 0 | 0.0 | 0 | 0.0 | 0 | 0.0 | |

- NHL, non-Hodgkin's lymphoma; BL, Burkitt's lymphoma; CIC, chronic inflammatory conditions.

Fever was the most common clinical characteristic (all non-Hodgkin's lymphoma = 83.3%, Burkitt's lymphoma = 88.6%, other non-Hodgkin's lymphoma = 78.3%, and chronic inflammatory conditions = 80.7%), followed by night sweats (Burkitt's lymphoma = 73.9%, other non-Hodgkin's lymphoma = 58.0%, and chronic inflammatory conditions = 74.2%), and weight loss (Burkitt's lymphoma = 65.9%, other non-Hodgkin's lymphoma = 54.3%, and chronic inflammatory conditions = 71.0%). Other common clinical characteristics were lymphadenopathy, facial swelling, and extra facial mass. Less than 11% of the children in the study were HIV-positive (all non-Hodgkin's lymphoma = 10.6%, Burkitt's lymphoma = 11.1%, other non-Hodgkin's lymphoma = 10.2%, and chronic inflammatory conditions = 6.9%), and all were positive for malaria. There was no statistically significant difference between children with non-Hodgkin's lymphoma, its subtypes, or chronic inflammatory conditions by clinical or demographic characteristics (Table I).

No statistically significant difference was observed when EBV viral load in saliva, whole blood and WBCs were compared in children with non-Hodgkin's lymphoma and those with chronic inflammatory conditions, nor was there any statistically significant difference in VCA-p18 IgG and EBNA1 serology in these children. However, when children with non-Hodgkin's lymphoma were compared to those with chronic inflammatory conditions, a statistically significant difference was found between normal and elevated EAd-IgG serology (OR 0.19, 95% CI 0.07, 0.51; P-value = 0.001), with children with non-Hodgkin's lymphoma having higher EAd-IgG values (Table II).

| All NHL | CIC | All NHL vs. CIC | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| N (%) | N (%) | OR (95% CI) | P-value | |

| 1. EBV viral load | ||||

| Saliva: Median EBV viral load (copies/ml) | ||||

| Low (0–2,000) | 29 (25.4) | 20 (26.3) | 1 | — |

| Intermediate (2,000–10,000) | 13 (11.4) | 5 (6.6) | 0.56 (0.17, 1.81) | 28 |

| High (>10,000) | 72 (63.2) | 51 (67.1) | 1.03 (0.52, 2.01) | 0.37 |

| Blood: Median EBV viral load (copies/ml) | ||||

| Low (0–2,000) | 44 (37.3) | 32 (41.0) | 1 | — |

| Intermediate (2,000–10,000) | 21 (17.8) | 14 (18.0) | 0.92 (0.41, 2.07) | 0.99 |

| High (>10,000) | 53 (44.9) | 32 (41.0) | 0.83 (0.44, 1.56) | 0.64 |

| White Blood Cell: Median EBV viral load (copies per 105 white blood cells) | ||||

| Low (0–2,000) | 54 (81.8) | 35 (83.3) | 1 | — |

| Intermediate (2,000–10,000) | 12 (18.2) | 7 (16.7) | 0.90 (0.32, 2.51) | 0.84 |

| High (>10,000) | 0 | 0 | — | — |

| 2. EBV serology | ||||

| VCA-p18 IgG (normalized value) | ||||

| Positive (1) | 1 (0.7) | 0 (0) | — | — |

| Normal (1–6) | 26 (19.3) | 20 (21.5) | 0.001–999 | 0.99 |

| Elevated (>6) | 108 (80.0) | 73 (78.5) | 0.88 (0.46, 1.69) | 0.70 |

| EBNA1-IgG | ||||

| Positive (1) | 2 (1.5) | 1 (1.1) | 1 | 0.49 |

| Normal (1–6) | 40 (29.6) | 34 (36.6) | 0.59 (0.05, 6.77) | 0.67 |

| Elevated (>6) | 93 (68.9) | 58 (62.4) | 0.73 (0.42, 1.29) | 0.28 |

| EAd-IgG | ||||

| Positive (1) | 25 (18.5) | 14 (15.0) | 1 | 0.28 |

| Normal (1–6) | 81 (60) | 74 (79.6) | 0.61 (0.29, 1.27) | 0.19 |

| Elevated (>6) | 29 (21.5) | 5 (5.4) | 0.19 (0.07, 0.51) | 0.001 |

- VCA-p18 IgG, viral capsid antigen; EBNA1-IgG, EBV nuclear antigen; EAd-IgG, early antigens.

There was no statistically significant difference found in EBV viral load in saliva in any of the disease categories considered; however, in whole blood there was a statistically significant difference between high and low viral loads when children with Burkitt's lymphoma were compared to those with other non-Hodgkin's lymphoma (OR 6.67, 95% CI 1.32, 33.69; P-value = 0.04). There was no statistically significant difference in EBV viral loads in WBCs when children with non-Hodgkin's lymphoma and those with chronic inflammatory conditions were compared. There was no statistically significant difference in VCA-p18 IgG, EBNA1 or EAd serology when children with Burkitt's lymphoma and those with other non-Hodgkin's lymphoma were compared. When children with Burkitt's lymphoma were compared to those with chronic inflammatory conditions, no significant difference was found in EBV viral loads or serology.

DISCUSSION

This article describes the clinical characteristics and markers of EBV infection in children with non-Hodgkin's lymphoma and chronic inflammatory conditions in Uganda. Overall, fever was the most common clinical characteristic at presentation, especially in Burkitt's lymphoma. Other common symptoms were night sweats, weight loss, extra facial mass, and lymphadenopathy. Lymphadenopathy was more common in children with other non-Hodgkin's lymphoma and chronic inflammatory conditions than in those with Burkitt's lymphoma. Apart from Burkitt's lymphoma, the other common subtypes of childhood non-Hodgkin's lymphoma were large cell lymphoma and diffuse large B-cell lymphoma. Comparisons of the frequency of clinical symptoms in children with different disease categories did not show statistically significant differences.

EBV viral load in whole blood was significantly higher in children with Burkitt's lymphoma compared to children with other non-Hodgkin's lymphoma. This difference was not reflected in the EBV viral load in saliva, indicating that a large fraction of circulating EBV DNA might originate from apoptotic fragments released from the tumor mass, rather than from circulating Burkitt's lymphoma tumor cells. The EBV-DNA levels observed in Burkitt's lymphoma patients were similar to those observed in previous reports from Kenya and Malawi, and much higher than those reported in regional healthy controls [Stevens et al., 1999; Asito et al., 2010]. High EA IgG serology, which is a marker of viral reactivation and of acute or chronic active EBV infection, was significantly present in children with non-Hodgkin's lymphoma. Finally, high to intermediate EBV viral loads in saliva and WBCs was noted in children with Burkitt's lymphoma, but there was no statistically significant difference in this factor between children with non-Hodgkin's lymphoma and those with chronic inflammatory conditions. However, the EBV viral load observed in both saliva and whole blood were elevated considerably in all children in this study, possibly reflecting chronic, or bystander activation of EBV due to poor nutritional or general health conditions, or alternative infectious or inflammatory conditions that may affect EBV latency control. This is in line with previous reports [Njie et al., 2009; Piriou et al., 2012].

The higher EBV viral load in whole blood observed in children with Burkitt's lymphoma compared to those with chronic inflammatory conditions is in line with previous observations [Stevens et al., 1999; Asito et al., 2010] and could be explained by enhanced viral lytic replication, or high turnover of (tumor) cells with latent EBV infection, which results in high levels of circulating tumor-derived DNA due to apoptosis. The latter hypothesis is most likely, because most circulating EBV DNA is fragmented and does not reflect intact virion DNA [Kawada et al., 2006]. The strong association of EBV viral load in blood and WBCs with Burkitt's lymphoma is in line with an earlier study on Burkitt's lymphoma, which compared EBV viral load and extent of disease [Asito et al., 2010]. No statistically significant elevation of EBV viral load in whole blood was observed in children with other non-Hodgkin's lymphoma and chronic inflammatory conditions. Recent studies have highlighted the importance of high EBV viral load in children with Plasmodium falciparum infection, and the role of EBV reactivation in disease etiology [Donati et al., 2006; Chene et al., 2007, 2011]. It has been hypothesized that this could be linked to the high risk of Burkitt's lymphoma in sub-Saharan Africa [Chene et al., 2011; Moormann et al., 2011]. In Kenya, EBV viral load was significantly higher in the blood samples of children aged 1–4 years from the malaria-holoendemic Kisumu District than those from the Nandi area, in which Burkitt's lymphoma is highly prevalent [Piriou et al., 2009, 2012]. Donati et al. [2006] also observed a high level of salivary shedding in African children, but did not observe a clear age relation.

The most intriguing observation in the present study is the association between non-Hodgkin's lymphoma and EA IgG, a known marker of both acute primary EBV infection and EBV reinfection. There was a highly statistically significant association between elevated EA IgG in children with non-Hodgkin's lymphoma compared to those with chronic inflammatory conditions. EA IgG is not usually expressed in healthy chronic carrier states, except when there is underlying viral replication in response to stress factors [Glaser et al., 2005]. This is also true for malignancies such as nasopharyngeal carcinoma, in which a high level of EA IgG is known to reflect reactivation of EBV infection and disease activity [Paramita et al., 2007]. Previous studies have indicated that certain serological markers of EBV are suitable for Burkitt's lymphoma diagnosis, but a detailed picture of EBV serology in childhood lymphoma and chronic inflammatory conditions in Africa is currently lacking [de-Thé et al., 1978; Geser et al., 1983]. The data in the present study point to a role for combined EA IgG and EBV viral load testing as a marker for EBV-related childhood non-Hodgkin's lymphoma. However, background factors such as infections and low immunity, including HIV infection and malnutrition, must be considered.

The findings of high to intermediate EBV viral load in saliva and WBCs may point to a possible role for EBV in other non-Hodgkin's lymphoma and chronic inflammatory conditions in children. The interphase between cell-bound EBV in WBCs and in the oral cavity, via the epithelial lining in the mouth, has been recognized as critical in viral shedding [Hadinoto et al., 2009]. An earlier study reported a very high level of EBV shedding in the oral cavity in families in Uganda [Mbulaiteye et al., 2006].

A possible weakness of the study is the large number of children excluded from the final analysis due to the difficulty of obtaining consent and assent from invited children in the original case-control study [Okello et al., 2013]. This could have introduced uncertainty, but that possibility is allayed by the comparability of included and excluded children with respect to clinical and demographic characteristics. A second weakness was the low capacity of the Ugandan laboratory to prepare the samples collected for the advanced laboratory procedures that would be applied in the Netherlands. Nevertheless, detailed subtyping was possible in 86% (Fig. 2) of the submitted tissue samples. Finally, healthy children were not enrolled as controls in the original case-control study due to ethical concerns, hence there was no disease-free comparison group.

The main strength of the study is the use of a sound diagnosis to assign children to the different disease categories. Diagnoses were based on histology performed at an external cancer reference laboratory and reliable clinical information collected by local investigators with experience in the evaluation of children with lymphoma in Uganda. Finally, the present study should stimulate new research on the role of EBV DNA and serology in the diagnosis and risk stratification of children with chronic, possibly EBV-associated, chronic inflammatory conditions. Evaluation of the spectrum of EBV-associated childhood malignancies and other conditions such as HIV and malaria in Uganda is important. Finally, a better understanding of the spread of EBV in the community and the implementation of preventive strategies such as vaccination are needed in developing countries.

In conclusion, the present study has shown that children with non-Hodgkin's lymphoma and chronic inflammatory conditions in Uganda present with similar clinical characteristics: fever, weight loss, and night sweats. These clinical features may suggest a common background process. They show that EBV viral load in blood is statistically significantly elevated in children with Burkitt's lymphoma, but not in children with other non-Hodgkin's lymphoma. A highly statistically significant expression of EA IgG in children with non-Hodgkin's lymphoma, but not those with chronic inflammatory conditions, was also observed. This may inform better design for clinical and preventive interventions for EBV-related illnesses in children in Uganda, and elsewhere in the future.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

Additional contributors are Dr Michael Odida and Dr Henry Wabinga of the School of Medicine, Makerere University College of Health Sciences, Kampala, Uganda for providing pathological data; Dr Hedy Juwana, Dr Sandra Verkuijlen, Dr Bogdan Mazuruk, and Dr Astrid Greijer of the Department of Pathology, VU University Medical Center, Amsterdam, the Netherlands for providing EBV serology and molecular analysis. The authors would like to thank the children who participated in this study and their families; Fred Okuku, David Sentongo, Laurence Olweny, and Irene Judith Nasozi for study support; Yusuf Mulumba and Pouran Almstedt for data management; Chris Meijer and Tineke Vendrig for initial detailed EBER and IHC tissue analysis; and Trudy Perdrix-Thoma for editorial assistance and language review. This study was financed by a grant from the Swedish International Development Cooperation Agency (SIDA) for the research collaboration between Makerere University and the Karolinska Institutet, Stockholm, Sweden.