Nationwide seroepidemiology of hepatitis B virus infection in South Korea in 2009 emphasizes the coexistence of HBsAg and anti-HBs

Abstract

Hepatitis B virus (HBV) infection is the major cause of chronic liver disease in Korea. This study investigated the seroprevalence of HBV infection with an emphasis on the coexistence of hepatitis B surface antigen (HBsAg) and antibody (anti-HBs). In all, 290,212 people undergoing health check-up examinations in 29 institutions during 2009 were recruited. The crude seroprevalences of HBsAg and anti-HBs was adjusted by age, sex, and geographic area using the 2009 estimated population of Korea. The adjusted seroprevalences of HBsAg and anti-HBs was 4.0% and 73.5%, respectively. Males showed higher HBsAg positivity and lower anti-HBs positivity than females (P < 0.001). HBsAg positivity increased with age from 3.5% in people 20–29 years old to 4.8% in people 40–49 years old, followed by a decrease in people ≥50 years old. HBsAg positivity in Southern provinces (4.5%) including Jeju (5.9%), was significantly higher than that in Central provinces (3.6%; P < 0.001). Interestingly, HBsAg and anti-HBs coexisted in 0.1% of the total subjects and in 2.9% of the HBsAg-positive group, showing distinct age distribution and higher alanine aminotransferase levels than those of the group positive for only HBsAg. In conclusion, the seroprevalence of HBsAg and anti-HBs in Korea varies significantly by age, sex and geographical location and coexisted in 2.9% of HBsAg-positive subjects. Continuous monitoring of seroepidemiology may facilitate the eventual eradication of HBV infection. J. Med. Virol. 85:1327–1333, 2013. © 2013 Wiley Periodicals, Inc.

INTRODUCTION

Korea is an endemic area of hepatitis B virus (HBV) infection, where it is the major cause of chronic liver disease [Kim et al., 1994, 2008]. Hepatitis B surface antigen (HBsAg) positivity accounts for 73% of chronic hepatitis and cirrhosis patients, and 79% of primary liver cancer patients, stressing the importance of HBV as a public health burden in Korea [Chae et al., 2009]. A domestic HBV vaccine was successfully developed in 1983 and the Korean government launched universal vaccination of infants in 1991. An active strategy for prevention of perinatal transmission was also successfully implemented in 2002. Those efforts resulted in a remarkable decrease in HBsAg positivity in the population, especially in children and adolescents [Choung et al., 2002].

The treatment paradigms for chronic hepatitis B have shown dramatic changes during last 20 years. Antiviral therapy with pegylated interferon alpha and several kinds of oral nucleos(t)ides analogues have improved the prognosis of HBV-related liver disease [Liaw et al., 2004; Hosaka et al., 2012]. The combined efforts of vaccination and the use of effective treatment regimens have contributed to a reduction in HBV-related liver disease mortality. From 1999 to 2009, the rank order of liver disease mortality among the whole causes of mortality in Korea decreased from fifth (23.4 per 100,000 people) to eighth (13.8 per 100,000 people) [Statistics Korea, 2009].

During the last 10 years, success in treating HBV has led to less attention being paid to the epidemiology of HBV. Although the Korea National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (KNHANES) includes HBsAg testing, its sample size does not permit calculation of more detailed epidemiological factors of seroprevalence. However, a report from Statistics Korea has documented that the prevalence of chronic liver disease differs by sex, age, and geographical area [Statistics Korea, 2009]. Also, a comprehensive survey of hepatitis B antibody (anti-HBs) positivity has not been reported, even though among HBsAg-positive people, a small fraction is also positive for anti-HBs. The implication of this phenomenon has been reported in several small-scale studies [Wang et al., 1996; Cha and Chae, 2000; Zhang et al., 2007; Jang et al., 2009], but no large-scale investigation of these patients has been conducted.

The aims of this study were to investigate the nationwide seroprevalence of HBsAg and anti-HBs in South Korea, and to evaluate the frequency and clinical characteristics of the coexistence of HBsAg and anti-HBs. This was accomplished using a large-scale survey of individuals who visited 29 health check-up institutions in all areas of the nation from January to December 2009.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Subjects

The study population was composed of 290,212 males and females ≥20 years old who visited health check-up institutions around South Korea between January and December 2009. The ethical committees of all participating institutions approved this study. The investigators were blind to the identity of participants, such as their name or registration number.

Data Analysis

Data on age, sex, geographic area, HBsAg, anti-HBs, and biochemical tests, including liver function tests, were collected from all subjects using an electronic data retrieval method from the hospital medical record system of each participating hospital. Age at the time of the examination was calculated. Serum HBsAg and anti-HBs were qualified according to the international laboratory standard in each institution [Yoo et al., 2006], and their results were expressed qualitatively as positive or negative, which meant that no quantitative results were analyzed. The cutoff criteria for a positive anti-HBs result was a titer >10 mIU/ml in all of the study institutions. The normal ranges of aspartate aminotransferase (AST) and alanine aminotransferase (ALT) were each defined as ≤40 IU/L. For convenience, the geographic areas of Korea were divided into 16 administrative districts (Seoul, Busan, Daegu, Gwangju, Daejeon, Ulsan, Gangwon, Gyeonggi, Chungbuk, Chungnam, Gyeongbuk, Gyeongnam, Jeonbuk, Jeonnam, and Jeju). Among the districts, the Southern provinces included Jeonnam, Jeonbuk, Gwangju, Gyeongnam, Gyeongabuk, Busan, Ulsanm Daegu and Jeju, while the Central provinces included Seoul, Gyeonggi, Gangwon, Incheon, Chungnam, Chungbuk, and Daejeon. The 2009 Korea Nutritional Statistical Office census was used To obtain the age-, sex-, and location-standardized prevalence.

Statistical Analysis

Continuous variables were expressed as the mean with standard deviation (SD) and range. Since the values of many biochemical laboratory tests were not normally distributed but left skewed, geometric means were compared with t-test. Prevalence values for categorical variables were tested using the χ2 tests. The correlation between positivity of HBsAg and anti-HBs according to geographical area was examined. Statistical analysis was conducted with IBM SPSS software version 20.0 (IBM, Chicago, IL) and a P-value <0.05 was considered to be statistically significant.

RESULTS

Seroprevalence of HBsAg in South Korea

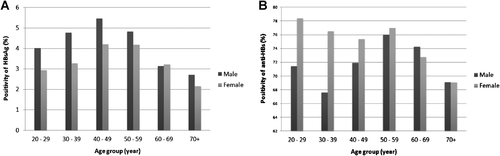

Among the 290,212 subjects, 177,954 (61.3%) were male ranging from 20 to 96 years of age. The overall seroprevalence of HBsAg adjusted by age, sex and geographical area was 4.0%. The seroprevalence of HBsAg increased with age, peaking in people 40–49 years of age, and decreased with age thereafter (Table I). The age- and geographical area- and adjusted HBsAg positivity was significantly higher in male (4.5%) than in female (3.4%; P < 0.001) except for those aged 60–69 (Fig. 1A). There was a statistically significant difference in HBsAg seropositivity by district (P < 0.001) such that HBsAg positivity in the Southern provinces (4.5%) was significantly higher than that in the Central provinces (3.6%) with the highest prevalence in Jeju.

| Population (2009) | Subject (n) | HBsAg(+) (n) | Crude rate (%) | Adjusted rate (%) | Adjusted variable | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sex | ||||||

| Male | 18,426,385 | 177,954 | 8,168 | 4.6 | 4.5 | Age and area |

| Female | 18,789,576 | 112,258 | 4,023 | 3.6 | 3.4 | |

| Age (years) | ||||||

| 20–29 | 7,015,200 | 8,246 | 280 | 3.4 | 3.5 | Sex and area |

| 30–39 | 8,184,646 | 70,328 | 2,628 | 3.7 | 4.0 | |

| 40–49 | 8,371,374 | 104,885 | 5,008 | 4.8 | 4.8 | |

| 50–59 | 6,351,452 | 72,335 | 3,281 | 4.5 | 4.5 | |

| 60–69 | 3,920,205 | 26,695 | 825 | 3.1 | 3.2 | |

| 70+ | 3,373,084 | 7,723 | 169 | 2.2 | 2.4 | |

| Area | ||||||

| Seoul | 7,917,892 | 85,747 | 3,262 | 3.8 | 3.5 | Sex and age |

| Busan | 2,739,593 | 7,778 | 390 | 5.0 | 4.7 | |

| Daegu | 1,857,146 | 11,379 | 506 | 4.4 | 4.2 | |

| Incheon | 1,991,894 | 12,038 | 488 | 4.1 | 3.6 | |

| Gwangju | 1,056,507 | 3,479 | 188 | 5.4 | 5.0 | |

| Daejeon | 1,122,764 | 4,955 | 228 | 4.6 | 4.5 | |

| Ulsan | 799,065 | 19,073 | 1,077 | 5.6 | 4.6 | |

| Gangwon | 1,121,538 | 9,521 | 420 | 4.4 | 3.7 | |

| Gyeonggi | 8,509,264 | 92,605 | 3,750 | 4.0 | 3.7 | |

| Chungbuk | 1,126,810 | 4,238 | 175 | 4.1 | 3.8 | |

| Chungnam | 1,498,867 | 16,200 | 571 | 3.5 | 2.9 | |

| Gyeongbuk | 2,037,890 | 5,814 | 261 | 4.5 | 3.9 | |

| Geyongnam | 2,363,984 | 3,889 | 191 | 4.9 | 4.5 | |

| Jeonbuk | 1,316,881 | 7,478 | 315 | 4.2 | 3.9 | |

| Jeonnam | 1,355,629 | 3,611 | 211 | 5.8 | 5.6 | |

| Jeju | 400,237 | 2,407 | 158 | 6.6 | 5.9 | |

| Total | 37,215,961 | 290,212 | 12,191 | 4.2 | 4.0 | Sex, age, and area |

- The Southern provinces (Jeonnam, Jeonbuk, Gwangju, Gyeongnam, Gyeongbuk, Busan, Ulsan, Daegu, and Jeju) and the central provinces (Seoul, Gyeonggi, Gangwon, Incheon, Chungnam, Chungbuk, and Daejeon) were divided.

The mean AST and ALT levels of the total subjects were 23.0 and 22.0 IU/L, respectively. The overall proportion of people with ALT levels >40 IU/L was 13.7%. The mean AST and ALT levels in the HBsAg positive group (27.2 and 27.5 IU/L, respectively) was significantly higher than that in HBsAg negative group (22.8 and 21.8 IU/L, respectively; P < 0.001).

Seroprevalence of Anti-HBs in South Korea

The overall seroprevalence of anti-HBs adjusted by age, sex, and geographical area was 73.5%. As shown in Table II, the area- and age adjusted anti-HBs positivity was significantly higher in female (75.4%) than in male (71.6%; P < 0.001; Table II), except for those ≥60 years of age (P < 0.001; Fig. 1B). The seropositivity of anti-HBs was highest in people 50–59 years old (76.5%) followed by those 20–29 years old (74.8%). Anti-HBs seropositivity showed significant differences according to geographic being highest in Incheon (75.7%) and lowest in Jeonnam (67.5%, P < 0.001). The anti-HBs seropositivity in the Southern provinces (72.6%) was significantly lower than in the Central provinces (74.1%, P < 0.001). The regions of higher HBsAg positivity showed lower anti-HBs positivity. There was a negative correlation between HBsAg and anti-HBs positivity (r = −0.487, P < 0.001).

| Population (2009) | Subject (n) | Anti-HBs(+) (n) | Crude rate (%) | Adjusted rate (%) | Adjusted variable | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sex | ||||||

| Male | 18,426,385 | 177,954 | 128,766 | 72.4 | 71.6 | Age and area |

| Female | 18,789,576 | 112,258 | 85,249 | 75.9 | 75.4 | |

| Age (years) | ||||||

| 20–29 | 7,015,200 | 8,246 | 6,237 | 75.6 | 74.8 | Sex and area |

| 30–39 | 8,184,646 | 70,328 | 50,396 | 71.7 | 71.9 | |

| 40–49 | 8,371,374 | 104,885 | 76,550 | 73.0 | 73.6 | |

| 50–59 | 6,351,452 | 72,335 | 55,568 | 76.8 | 76.5 | |

| 60–69 | 3,920,205 | 26,695 | 19,854 | 74.4 | 73.5 | |

| 70+ | 3,373,084 | 7,723 | 5,410 | 70.1 | 69.1 | |

| Area | ||||||

| Seoul | 7,917,892 | 85,747 | 64,007 | 74.6 | 74.6 | Sex and age |

| Busan | 2,739,593 | 7,778 | 5,837 | 75.0 | 74.4 | |

| Daegu | 1,857,146 | 11,379 | 8,295 | 72.9 | 73.1 | |

| Incheon | 1,991,894 | 12,038 | 9,173 | 76.2 | 75.7 | |

| Gwangju | 1,056,507 | 3,479 | 2,457 | 70.6 | 71.6 | |

| Daejeon | 1,122,764 | 4,955 | 3,663 | 73.9 | 73.5 | |

| Ulsan | 799,065 | 19,073 | 13,891 | 72.8 | 72.4 | |

| Gangwon | 1,121,538 | 9,521 | 6,500 | 68.3 | 68.3 | |

| Gyeonggi | 8,509,264 | 92,605 | 68,305 | 73.8 | 74.5 | |

| Chungbuk | 1,126,810 | 4,238 | 3,024 | 71.4 | 71.4 | |

| Chungnam | 1,498,867 | 16,200 | 11,979 | 73.9 | 73.7 | |

| Gyeongbuk | 2,037,890 | 5,814 | 4,221 | 72.6 | 71.1 | |

| Geyongnam | 2,363,984 | 3,889 | 2,898 | 74.5 | 73.9 | |

| Jeonbuk | 1,316,881 | 7,478 | 5,566 | 74.4 | 74.3 | |

| Jeonnam | 1,355,629 | 3,611 | 2,507 | 69.4 | 67.5 | |

| Jeju | 400,237 | 2,407 | 1,692 | 70.3 | 71.6 | |

| Total | 37,215,961 | 290,212 | 214,015 | 73.7 | 73.5 | Sex, age, and area |

- The Southern provinces (Jeonnam, Jeonbuk, Gwangju, Gyeongnam, Gyeongbuk, Busan, Ulsan, Daegu, and Jeju) and the central provinces (Seoul, Gyeonggi, Gangwon, Incheon, Chungnam, Chungbuk, and Daejeon) were divided.

Coexistence of HBsAg and Anti-HBs

HBsAg and anti-HBs coexisted in 353 individuals, which comprised 0.1% of the total subjects and 2.9% of the HBsAg-positive group. This group showed significantly different age distribution from the HBsAg single-positive group (P = 0.024). The coexistence group also progressively increased with age from 30 to 70, while the HBsAg rate peaked at 40–49 years of age and decrease thereafter, however, the proportion of subjects ≥50 years old was higher in the coexistence group than in the HBsAg single positive group. The coexistence group showed significantly higher AST and ALT levels (30.7 and 31.5 IU/L, respectively) than the sole positive group for HBsAg (27.1 and 27.4 IU/L, respectively; P < 0.001; Table III).

| HBsAg (+), anti-HBs (−) n = 11,838 | HBsAg (+), anti-HBs (+) n = 353 | P-value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Sex | |||

| Male, n (%) | 7,936 (65.4%) | 232 (66.7%) | 0.604 |

| Female, n (%) | 3,902 (32.0%) | 121 (34.8%) | |

| Age (years) | |||

| 20–29, n (%) | 268 (2.2%) | 12 (3.4) | 0.024 |

| 30–39, n (%) | 2,558 (21.0%) | 70 (20.1) | |

| 40–49, n (%) | 4,877 (40.0%) | 131 (37.6) | |

| 50–59, n (%) | 3,184 (26.1%) | 97 (27.9) | |

| 60–69, n (%) | 792 (6.5%) | 33 (9.5) | |

| 70+, n (%) | 159 (1.3) | 10 (2.9) | |

| AST | |||

| Meana ± SD (IU/L) | 27.1 ± 1.5 | 30.7 ± 1.7 | <0.001 |

| ALT | |||

| Meana ± SD (IU/L) | 27.4 ± 1.8 | 31.5 ± 2.0 | <0.001 |

- AST, aspartate aminotransferase; ALT, alanine aminotransferase.

- a Geometric mean, χ2 for sex, age; t-test for AST, ALT.

DISCUSSION

It is important to investigate the changing epidemiology of HBV infection to estimate the disease burden and to establish the public health policy related to HBV infection. This is the first study of the nationwide seroprevalence of HBsAg and anti-HBs in South Korea adjusted by age, sex, and geographical area of the estimated population of Korea in 2009. The results show that the overall seroprevalence of HBsAg among adults over 20 years old was 4.0% and that of anti-HBs was 73.5%. HBV seroepidemiology significantly varied with age, sex, and geographical area. Among the HBsAg-positive, 2.9% showed coexistence of HBsAg and anti-HBs and their characteristics differed significantly compared to those of the HBsAg-positive group.

Until the 1980s, the prevalence of HBV in Korea was almost 8% of the general population [Ahn, 1982; Chi and Kim, 1988]. KNHANES reported that the overall prevalence of HBsAg among those older than 10 years has decreased from 4.6% in 1998 and 3.7% in 2005 to 3.2% in 2009. According to KNHANES, while the overall HBsAg seroprevalence in those ≥10 years of age in 2009 was 3.2%, the seroprevalence in those ≥30 years of age was 4.0%. In this study, the age-, sex-, and geographical area-adjusted overall seroprevalence of HBsAg in those ≥20 years of age was 4.0%. When the data were re-examined, the overall seroprevalence in those ≥30 years of age was 4.1%, which was very close to the previous Korean survey results. Therefore, the results of this study reflect the standardized seroprevalence of HBsAg of Korea, although this study population comprised health-check examinees rather than the general population. HBsAg seroprevalence has been reduced by half during the past 30 years, probably due to the combined effect of vaccination and antiviral therapy. These results suggest that the decrease in HBsAg seroprevalence may accelerate in the future.

The seropositivity of HBsAg in this study increased with age from 20 to 40 years old, then decreased thereafter, which is comparable to other reports [Chae et al., 2009; Kim et al., 2009]. The reasons for decreasing seroprevalence in those over age 50 may be related to the natural loss of HBsAg and death from liver diseases such as cirrhosis or hepatocellular carcinoma [Lee et al., 2011]. Concerning the geographic differences of HBsAg seroprevalence in Korea, a previous study reported similar HBsAg seropositivity in several administrative areas with the exception of Jeju, where HBsAg seropositivity was approximately three times higher and anti-HBs positivity significantly lower than those of the national average in 1998 [Lee et al., 2002; Kang et al., 2004]. Jeju is an island on which the relatively limited population migration and inadequate vaccination may explain these findings. The regions of higher HBsAg positivity showed lower anti-HBs positivity. The 2009 report of Statistics Korea showed that the prevalence of chronic liver disease differs by sex, age, and geographical areas [Statistics Korea, 2009]. The Jeonnam province had the highest liver disease mortality rate (16.6 per 100,000), while Daejeon had the lowest rate (8.7 per 100,000). Those patterns of prevalence and mortality of liver disease may be partially related to the altered prevalence of hepatitis B according to age, sex, and geographic area because HBV is the major cause of liver disease in Korea.

Research into anti-HBs seroprevalence in Korea has been limited in the last 10 years [An et al., 2006]. However, the previous Korean survey (KNHANES) did not survey anti-HBs after 1998, when it reported that anti-HBs seropositivity was 57.0% in males and 58.9% in females. The present data showed that age, sex, and geographical area-adjusted anti-HBs positivity in 2009 was 71.6% in males and 75.4% in females. The HBV vaccine response has been superior in females than in males [Fang et al., 1994; Zeeshan et al., 2007], and this result was compatible with previous studies in Korea [Park et al., 2003; Kim et al., 2009]. Anti-HBs positivity means recovery from HBV or immunization after vaccination. Considering that the prevalence of anti-HBc increased markedly with age [Joo et al., 1999] and that HBsAg seropositivity has been gradually decreasing with time, the increase of anti-HBs positivity since 1998 likely primarily be the result of vaccination programs and to a lesser extent, the result of recovery from infection.

HBsAg and anti-HBs coexisted in 2.9% of HBsAg carriers, which is lower than previously reported results of 3–10% [Wang et al., 1996; Cha and Chae, 2000; Zhang et al., 2007; Jang et al., 2009]. In the past, the coexistence of HBsAg and anti-HBs was regarded simply as superinfection with a different subtype of HBV [Heijtink et al., 1982; Shiels et al., 1987], suggesting no significant protective or pathogenic effect. However, recent studies have shown that the coexistence of HBsAg and anti-HBs is associated with high replicative activity of HBV and mutations in the viral surface gene around the “a” determinant, which may alter the antigenicity of HBsAg and lead to subsequent failure of anti-HBs neutralization. These escape mutants, which contain a G to R substitution at amino acid 145 of HBsAg, have been described in hepatic graft recipients or vaccinated newborns from HBsAg positive mothers [Ho et al., 1998]. Another study reported that coexistence of HBsAg and anti-HBs in 2.8% in chronic HBV-infected patients (13/459) and nine of 13 patients were in immunosuppressive conditions including kidney transplantation, human immunodeficiency virus infection, prolonged corticosteroid therapy or immunosuppressive chemotherapy[Colson et al., 2007]. The median titers of anti-HBs were 22 IU/L, and HBV DNA levels were very high, suggesting active HBV replication. The HBsAg from these patients harbored mutations that may escape from neutralization by anti-HBs, resulting in a significant variability within the reverse transcriptase (RT) region overlapping the C terminal region of HBsAg. Higher variability in the RT region may be implicated in antiviral resistance [Heijtink et al., 1982; Shiels et al., 1987; Zhang et al., 2007]. In this study, the concurrent positive group of HBsAg and anti-HBs showed increasing prevalence with age, and significantly higher AST and ALT level than the HBsAg only group. This result may suggest that mutations in the HBs gene accumulate with age under a modest immune response, which may provoke persistent hepatic inflammation. Therefore, those patients with both HBsAg and anti-HBs may not lose their HBsAg, however, there have been no study of the natural course of these patients. Although this study did not investigate the presence of immune suppressive condition or severity of liver disease in the coexistence group, this group may be at high risk of severe disease and should be studied in the future.

The major limitation of this study is that subjects were voluntary health-check persons rather than general population. The other limitation is the lack of the detailed data such as quantitative HBsAg or anti-HBs results, body mass index, history of potentially hepatotoxic drug use, alcohol consumption, and clinical diagnosis of HBsAg-positive patients. However, as discussed above, results concerning HBsAg prevalence were very similar to the standardized prevalence reported in the National Korean survey (KNHANES) of the same year, which was representative of national data.

In conclusion, this is the first report of significant differences in HBV seroprevalence based on geographical area in Korea, and the coexistence of HBsAg and anti-HBs in such a large population. Continuous monitoring of seroepidemiology will facilitate eradication of HBV infection in this longstanding HBV endemic area of the world; moreover, the significance of the coexistence of HBsAg and anti-HBs should be studied further.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank to Korean Hepatitis Epidemiology Study Group members for the data collection and statistical support as the authors of this.

Korean Hepatitis Epidemiology Study Group includes the following researchers:

Byung Seok Lee,1 Yong Kyun Cho,2 Sook-Hyang Jeong,3 In Hee Kim,4 Kwang-Hyub Han,5 Do Young Kim,5 Joon Hyeok Lee,6 Young-Joo Jin,7 Don Lee,7 Dong Jin Suh,7 Sun Jae Lee,8 Kyung-Ah Kim,9 Young Kul Jung,10 Hyung Joon Yim,11 Youn Jae Lee,12 Jeong Heo,13 Dong Joon Kim,14 Soon Koo Baik,15 Dae Hee Choi,16 Young Seok Kim,17 Hee Bok Chae,18 Ha Yan Kang,19 Won Young Tak,20 Heon Ju Lee,21 Neung Hwa Park,22 Woo Jin Chung,23 Sung-Kyu Choi,24 Kim Man Woo,25 Eun-Young Cho,26 Byung-Cheol Song,27 Moran Ki28

Departments of Internal Medicine, 1Chungnam National University School of Medicine, 2Kangbuk Samsung Hospital, 3Seoul National University Bundang Hospital, 4Chonbuk National University School of Medicine, 5Yonsei University College of Medicine, 6Seoul Samsung Hospital, 7Seoul Asan Hospital, 8Korea University Guro Hospital, 9Inje University Ilsan Paik Hospital, 10Gachon College of Medicine, 11Korea University Ansan Hospital, 12Inje University Pusan Paik Hospital, 13Pusan National University School of Medicine, 14Hallym University College of Medicine, 15Yonsei University Wonju College of Medicine, 16Kangwon National University, 17School of Medicine, Soonchunhyang University College of Medicine, 18Chungbuk National University College of Medicine, 19Dankook University College of Medicine, 20Kyungpook National University College of Medicine, 21Yeungnam University, College of Medicine, 22University of Ulsan College of Medicine, 23Keimyung University School of Medicine, 24Chonnam National University Medical School, 25Chosun University Hospital, 26Wonkwang University College of Medicine, 27Jeju National University, Department of Preventive Medicine, 28Eulji University School of Medicine.