Prevalence and clinical significance of hepatitis D virus co-infection in patients with chronic hepatitis B in Korea

Abstract

Hepatitis D virus (HDV) infection can cause severe acute and chronic liver disease in patients infected with hepatitis B virus (HBV). Despite the significant decline in the global HDV infection, it remains a major health concern in some countries. This study aimed to investigate the prevalence and clinical features of HDV co-infection in patients with chronic HBV infection in Korea, where HBV infection is endemic. Nine hundred forty patients [median age, 48 (18–94) years; men, 64.5%] infected chronically with HBV were enrolled consecutively. All patients who were positive for hepatitis B surface antigen (HBsAg) for at least 6 months and were tested for anti-HDV. A portion of the HDV delta antigen was amplified, sequenced, and subjected to molecular and phylogenetic analysis using sera from the patients who were anti-HDV positive. Clinical features and virologic markers were evaluated. Inactive HBsAg carriers, chronic hepatitis B, cirrhosis and hepatocellular carcinoma accounted for 29.5%, 44.7%, 17.9%, and 8.0%, respectively. Only three patients were positive for anti-HDV, corresponding to a 0.32% positive rate. All patients who were positive for anti-HDV were inactive HBsAg carriers. HDV RNA could be amplified by PCR from the sera of two patients. Phylogenetic analysis showed that both carried HDV genotype 1. In conclusion, the prevalence of HDV infection is very low (0.32%) in Korea. All HDVs were genotype 1 and detected in inactive HBsAg carriers. Therefore, HDV co-infection may not have a significant clinical impact in Korean patients with chronic HBV infection. J. Med. Virol. 83:1172–1177, 2011. © 2011 Wiley-Liss, Inc.

Abbreviations:

HBeAg, hepatitis B e antigen; anti-HBe, antibody to hepatitis B e antigen; HBsAg, hepatitis B surface antigen; HBV, hepatitis B virus; HCC, hepatocellular carcinoma; HCV, hepatitis C virus; HDV, hepatitis D virus; HIV, human immunodeficiency virus.

INTRODUCTION

The hepatitis D virus (HDV) is a defective RNA virus that requires the hepatitis B virus (HBV) for its replication and transmission [Rizzetto et al., 1977]. It can cause both acute and chronic manifestations and leads to more severe liver disease than HBV mono-infection, although the severity of disease may vary widely [Niro et al., 1997]. Approximately 5% of HBV carriers worldwide are known to be co-infected with HDV, which has been classified into at least eight genotypes [Wedemeyer and Manns, 2010]. While HDV appears to span different geographic distributions, its general pattern is parallel to that of HBV. HDV is endemic in Mediterranean countries, the Middle East, Central Africa, and northern parts of South America. Although the prevalence of HDV infection has declined globally as a result of HBV vaccination and improvement of socio-economic conditions [Gaeta et al., 2000], it remains a relevant cause of morbidity in some countries [Viana et al., 2005; Oyunsuren et al., 2006; Khan et al., 2008]. There is even a resurgence in Western Europe owing to immigration from highly endemic areas [Gaeta et al., 2007; Wedemeyer et al., 2007; Cross et al., 2008].

Although the prevalence of chronic HBV infection in Korea has declined after universal HBV vaccination, HBV infection is still endemic in the country and is one of the most common causes of chronic liver disease in Korea [Jang et al., 2001]. However, studies on the epidemiology of HDV co-infection with HBV in Korea are scant [Kim et al., 1985, 1989; Suh, 1985; Choi et al., 1987; Jung et al., 2005]. This study aimed to investigate the prevalence and clinical features of HDV co-infection in patients infected chronically with HBV in Korea.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Patients and Study Design

Nine hundred forty patients with chronic HBV infection at Kangdong Sacred Heart Hospital of Hallym University Medical Centre, Seoul, Korea, were enrolled consecutively from January 2008 to October 2010.

All patients were positive for hepatitis B surface antigen (HBsAg) for at least 6 months and were tested for antibody against hepatitis D virus (anti-HDV). Serum samples were also screened for hepatitis e antigen (HBeAg), antibody to HBeAg (anti-HBe), HBV DNA, and antibody to hepatitis C virus (anti-HCV). Demographic and laboratory data at the time of anti-HDV screening were used. The severity of liver disease was classified as follows: (1) inactive HBsAg carriers were those who were HBsAg-positive for more than 6 months, were HBeAg-negative, had a serum HBV DNA levels <104 copies/ml, and had persistently normal serum ALT levels for more than 1 year; (2) patients with chronic hepatitis B were those who had serum HBV DNA levels >104 copies/ml, persistently or intermittently elevated serum ALT levels and a lack of evidence for the presence of cirrhosis and hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) [Lok and McMahon, 2007]; (3) cirrhosis was diagnosed by histological examination and/or ultrasonographic/CT imaging features, with accompanying clinically relevant portal hypertension (esophageal and/or gastric varices, ascites, splenomegaly with a platelet count of <100,000/mm3) or hepatic encephalopathy; (4) diagnosis of HCC was made according to the guidelines of the American Society for the Study of Liver Diseases, which is based on imaging studies and serum alpha-fetoprotein levels [Bruix and Sherman, 2005].

This study was approved by the Investigation and Ethics Committee for Human Research at the Hallym University Medical Centre, Seoul, Korea.

Laboratory and Virological Assay

Routine biochemical tests were performed using standard laboratory procedures. HBsAg, HBeAg, and anti-HBe were measured using a micro-particle enzyme immunoassay (Abbott Laboratories, North Chicago, IL). Serum HBV DNA levels were measured by the VERSANT 3.0 Assay (Bayer Healthcare, Tarrytown, NY; lower limit of detection: 2,000 copies/ml) or COBAS TaqMan PCR assay (Roche, Branchburg, NJ; lower limit of detection: 116 copies/ml). Anti-HCV was measured using a chemiluminescent micro-particle enzyme immunoassay (ARCHITECT anti-HCV; Abbott Diagnostics, Wiesbaden, Germany), and anti-HDV, by enzyme immunoassay using ETI-AB-DELTAK-2 (Diasorin, Vercelli, Italy).

Detection of Viral Nucleic Acids and Sequencing

Serum HDV RNA was extracted using commercial kits (QIAGEN, Hilden, Germany), according to the manufacturer's protocol. All serum samples were stored at −70°C until analysis. Conserved regions of HDV were amplified by RT-PCR using the amplification primers and thermo-cycling conditions described previously [Niro et al., 1997]. The following primer sequences were used: forward 5′-GCC CAG GTC GGA CCG CGA GGA GGT-3′, reverse 5′-ACA AGG AGA GGC AGG ATC ACC GAC-3′ for the primary PCR; the nested primer sequences were as follows: forward 5′-GAG ATG CCA TGC CGA CCC GAA GAG-3′, and reverse 5′-GAA GGA AGG CCC TCG AGA ACA AGA-3′. The PCR products were purified by a QIAEX II Gel Extraction Kit (QIAGEN) and directly sequenced using an ABI PRISM BigDye™ Terminator Cycle Sequencing Ready Reaction Kit (Applied Biosystems, Inc., Foster, CA) on an ABI automated fluorescent sequencer (ABI 3730xl; Applied Biosystems, Inc.).

Phylogenetic Analyses

The nucleotide sequences of HDV were compared to 40 reference strains of HDV genotypes 1–8. The sequences were subjected to alignment with ClustalX V2.0 software [Larkin et al., 2007]. A phylogenetic tree was constructed using the neighbor-joining algorithm implemented in MEGA version 4.0 software [Tamura et al., 2007]. The reliability of the inferred tree was assessed by a bootstrap re-sampling test including 1,000 replications.

Statistical Analysis

Chi-square analysis or Fisher's exact test for categorical variables was used where applicable. A value of P < 0.05 was considered statistically significant. Statistical analysis was performed using SPSS version 18.0 (Chicago, IL).

RESULTS

Characteristics of the Patients

The median age was 48 (18–94) years and 64.5% (606 out of 940) of the patients were male. Three hundred forty-seven patients were tested positive for HBeAg (36.9%). Inactive HBsAg carriers, chronic hepatitis B, cirrhosis, and HCC accounted for 29.5% (277/940), 44.7% (420/940), 17.9% (168/940), and 8.0% (75/940) of the patients, respectively. Of the patients with chronic HBV infection, 16 patients (1.7%) had a super-infection with chronic hepatitis C. Three of the 940 patients were positive for anti-HDV, generating a positive rate of 0.32%. The baseline characteristics of the patients are summarized in Table I. All patients who were tested positive for anti-HDV were inactive HBsAg carriers and not co-infected with HCV or HIV. Their clinical characteristics are summarized in Table II. Among the patients with HDV co-infection, only one had a family history of HBV infection and the others presented with no other risk factors for transmission, such as history of intravenous drug use, family history of liver disease, surgery, transfusion, or multiple sexual partners. An additional 10 patients with acute hepatitis B were tested for anti-HDV during the same period to assess the possibility of simultaneous HBV and HDV infection. However, none of those patients were infected with HDV.

| Variables | Total (n = 940) |

|---|---|

| Age (years) | 48 (18–94) |

| Male (%) | 606 (64.5%) |

| HBeAg positive (%) | 347 (36.9%) |

| Severity of liver disease (%) | |

| Inactive HBsAg carrier | 277 (29.5%) |

| Chronic hepatitis B | 420 (44.7%) |

| Liver cirrhosis | 168 (17.9%) |

| HCC | 75 (8.0%) |

| HBV DNA [log(copies/ml)] | 4.10 (2.06–8.99) |

| Serum total bilirubin (mg/dl) | 0.8 (0.2–40.3) |

| Serum albumin (g/dl) | 4.1 (0.6–5.6) |

| INR | 1.03 (0.70–4.66) |

| Platelet (mm3) | 190.5 (12.0–651.0) |

| Serum AST (IU/L) | 30 (8–2232) |

| Serum ALT (IU/L) | 30 (5–2542) |

| Anti-HCV positive (%) | 16 (1.7%) |

| Anti-HDV positive (%) | 3 (0.32%) |

| HIV positive (%) | 2 (0.21%) |

- HBeAg, hepatitis B e antigen; HBsAg, hepatitis B surface antigen; HCC, hepatocellular carcinoma; HBV, hepatitis B virus; INR, international normalized ratio; AST, aspartate aminotransferase; ALT, alanine aminotransferase; HCV, hepatitis C virus; HDV, hepatitis D virus; HIV, human immunodeficiency virus.

- Data are expressed as median (range) or number.

| Patients | Age/sex | HBeAg/Ab | HBV DNA (copies/ml) | ALT (IU/L) | HDV RNA |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 48/M | −/+ | 569 | 14 | + |

| 2 | 32/F | −/+ | <116 | 20 | + |

| 3 | 79/F | −/+ | <2000 | 16 | − |

- HBeAg, hepatitis B e antigen; HBeAb, antibody to hepatitis B e antigen; HBV, hepatitis B virus; ALT, alanine aminotransferase; HDV, hepatitis D virus; M, male; F, female.

Molecular and Phylogenetic Analyses of Co-Infecting HDV

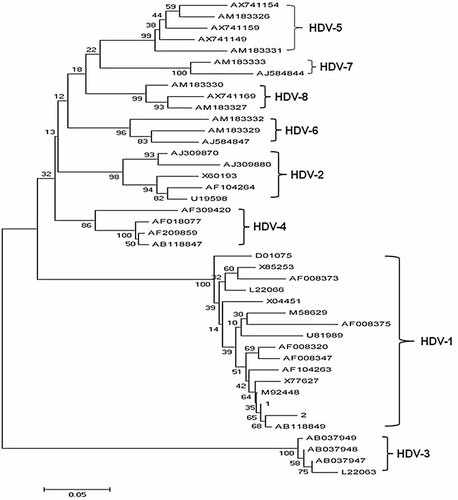

HDV RNA was detected in two of the three patients who were tested positive for anti-HDV. The 357-bp sequences of the hepatitis delta antigen obtained from patients with HDV infection were compared to the corresponding sequences from 40 reference strains of HDV genotypes 1–8 retrieved from GenBank. All Korean isolates were branched as HDV genotype 1 with a bootstrap value of 100%, based on 1,000 replicates (Fig. 1).

The 357-bp sequences of the hepatitis delta antigen obtained from the two patients with HDV infection were compared to the corresponding sequences from 40 reference strains of HDV genotypes 1–8. All Korean isolates were branched as HDV genotype 1.

DISCUSSION

HBV infection is a global health problem, and more than 350 million people worldwide are infected chronically with HBV. It has been estimated that approximately 5% of the HBsAg carriers worldwide are co-infected with HDV, resulting in 15–20 million HDV carriers globally [Wedemeyer and Manns, 2010]. The main regions where HDV is prevalent are the Mediterranean basin, the Middle East, Central and Northern Asia, West and Central Africa, the Amazonian basin, Venezuela, Columbia, and certain Pacific islands [Pascarella and Negro, 2011]. Although the geographical distribution of HDV infection might be expected to mirror that of HBV, the rate of HDV infection is not a simple reflection of that of HBV. Korea is well known as a region where HBV infection is endemic, but there have been few studies on the prevalence of HDV infection, which ranges from 0% to 3.6% [Kim et al., 1985, 1989; Suh, 1985; Choi et al., 1987; Jung et al., 2005]. The varying rates of HDV prevalence might be attributable to heterogeneity of the patient population based on differing modalities of patient recruitment.

To date, six studies, including ours, have been conducted on the prevalence of HDV infection in Korea. The prevalence of HDV co-infection in Korean patients with chronic HBV infection was 0.92% (17/1,842). There was no significant difference between HDV infection in the 1980s and 2000s [0.99% (7/708) vs. 0.88% (10/1134), P = 0.807]. Although the prevalence of HDV infection in Korea is considered very low, such findings remain inconclusive because previous studies were conducted in a relatively small number of patients with chronic HBV infection. To our knowledge, this is the largest study on the prevalence HDV infection in Korea to date. In this study, the prevalence of HDV infection in Korean patients with chronic HBV infection was 0.32%, and this finding is in accordance with that of previous studies. In addition, as mentioned above, there was no significant change in the prevalence of HDV infection in Korea for the past 20 years, based on the data of previous studies. Thus far, there has been no report on the molecular epidemiology of HDV in Korea as well, and therefore, an attempt was made to identify the HDV genotype by using a phylogenetic tree. The HDV detected in Korean patients with chronic HBV infection were all of genotype 1. Genotype 1 is the most common HDV genotype worldwide and displays varying pathogenicity. On the other hand, the other genotypes are usually found in specific geographical regions. For example, genotypes 2 and 4 are predominant in the Far East. Genotype 3 is associated with HBV genotype F and fulminant hepatitis in South America, and genotypes 5–8 are found mainly in Africa. HDV genotype 1 has a wider distribution owing to its interaction with HBV, which is more efficient than other HDV genotypes [Hsu et al., 2002; Shih et al., 2008, 2010].

Several studies have shown that chronic HDV infection leads to more severe liver disease than chronic HBV mono-infection. Infection with HDV is associated with an accelerated course of fibrosis progression, an increased risk of HCC, and early decompensation of cirrhosis [Wedemeyer and Manns, 2010]. Overall, the relative risk of developing cirrhosis, HCC, and/or death during follow-up in patients co-infected with HBV and HDV is 2-, 3- and 2-fold, respectively, compared to that in patients with HBV mono-infection [Fattovich et al., 2000, 2008]. Other studies, however, have shown that HDV co-infection did not increase risk of progression to liver cirrhosis or HCC in patients with chronic HBV infection [Huo et al., 1996, 2000; Liaw et al., 2004]. It is well known that HDV infection is associated with reduced levels of HBV DNA [Wu et al., 1995; Sakugawa et al., 2001; Heidrich et al., 2009]. The current study also showed that all three patients with HDV co-infection had low HBV DNA levels, that is, less than 2,000 copies/ml, and were classified as inactive HBsAg carriers. In this study, none of the patients with advanced liver disease had HDV infection. Even when examined in combination with the total number of studies carried out in Korea, there was no significant difference between the prevalence of HDV infection in patients with mild liver disease (inactive HBsAg carrier and chronic hepatitis B) and those with advanced liver disease (cirrhosis and HCC) [0.65% (8/1223) vs. 1.45% (9/619), P = 0.120]. This suggests that HDV infection does not influence the clinical course of Korean patients with chronic HBV infection. However, the impact of HDV co-infection on chronic HBV infection is still inconclusive because the prevalence of HDV infection in the present study (0.32%) is rather low.

HDV infection spreads in the same manner as HBV infection, mainly through parenteral exposure, whereas perinatal transmission of HDV is rare [Pascarella and Negro, 2011]. It is well known that perinatal transmission, from mother to neonate, is the principal route of HBV transmission in the Far East, including Korea. It might be responsible for the paradoxical prevalence of HBV and HDV infection in the Far East.

In conclusion, the prevalence of HDV infection is very low (0.32%) in Korea, where HBV infection is endemic, and only genotype 1 of HDV was detected. In addition, HDV co-infection may not affect the clinical course in chronic HBV infection in Korea because of both its low prevalence and its detection only in patients with mild liver disease, such as inactive HBsAg carriers.