Efficacy of interferon-based antiviral therapy in patients with chronic hepatitis C infected with genotype 5: A meta-analysis of two large prospective clinical trials

Abstract

The characteristics and response rate to pegylated interferon and ribavirin (PEG-INF + RBV) of patients with chronic hepatitis C infected with genotype 5 are poorly documented. A meta-analysis of two large phase III/IV prospective randomized clinical trials conducted in Belgium in patients with chronic hepatitis C (n = 1,073 patients) was performed in order to compare the response to antiviral therapy of hepatitis C virus (HCV) genotype 5 with that of other HCV genotypes. A subset of HCV-1 infected patients selected from within the study database were selected to match the HCV-5 sample for known prognostic factors. In Belgium HCV-5 is responsible for a significant minority of cases of chronic hepatitis C CHC (4.5%) and is characterized by a more advanced age (58.4 years), a high frequency of cirrhosis (27.7%), a specific mode of HCV acquisition, and a particular geographic origin (66.7% of patients from West Flanders). The primary comparative analysis showed that response to treatment with PEG-INF + RBV of HCV-5 is similar to HCV-1 and lower compared to HCV-2/3. The analysis of the matched patient subgroup demonstrates that the HCV-5 “intrinsic sensitivity” to PEG-IFN + RBV therapy is identical to HCV-1, with a sustained virological response of 55% in both groups. In contrast to previous publications, this meta-analysis suggests that HCV-5 response to treatment is closer to HCV-1 than to HCV-2/3 and suggests that in Belgium HCV-5 infection should be treated with the same antiviral regimen as HCV-1. J. Med. Virol. 83:815–819, 2011. © 2011 Wiley-Liss, Inc.

Abbreviations:

HCV, hepatitis C virus; PEG-INF, pegylated interferon; RBV, ribavirin.

INTRODUCTION

At least six major genotypes of hepatitis C virus (HCV) have been identified, each comprising multiple subtypes. HCV genotype 5 (HCV-5) shows a worldwide distribution mainly restricted to South Africa where it has been observed in up to 30% of HCV infected patients [Simmonds, 1995]. In other parts of the world genotype 5 is a minor component of the population infected with HCV [Blatt et al., 2000; Ross et al., 2000] except in a few restricted areas of higher prevalence [Jover et al., 2001; Henquell et al., 2004; Verbeeck et al., 2007]. In Belgium, the overall prevalence of HCV infection is estimated to be 0.9% of the population according to HCV antibody screening [Beutels et al., 1997] and the repartition of genotypes reflects the trends in Europe and the US: 68% genotype 1, 23% genotypes 2 or 3, and 3, 9% other genotypes [Kleter et al., 1998; Gerard et al., 2005].

Relatively little sequence heterogeneity is found within genotype 5 [Chamberlain et al., 1997; Verbeeck et al., 2005]. The characteristics and response rate of patients with chronic hepatitis C infected with HCV-5 to interferon-based therapy has been poorly documented to date, but the suggestion is that HCV-5 responds better to therapy than HCV-1 [Legrand-Abravanel et al., 2004; Delwaide et al., 2005; Bonny et al., 2006; Antaki et al., 2008]. An accurate comparison of the sensitivity of genotype 5 to treatment with other better known genotypes should allow a better evaluation of response to treatment and will help to define the optimal treatment regimen of this rare genotype. Because of the small size of the genotype 5 population large single studies are difficult to perform. Meta-analyses and matched subgroup analysis of genotype 5 response to treatment are an alternative. Two large clinical trials who assessed the antiviral effect of pegylated interferon and ribavirin (PEG-INF + RBV) have been performed in Belgium. They offer a unique opportunity for studying patients with chronic hepatitis C infected by HCV-5.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

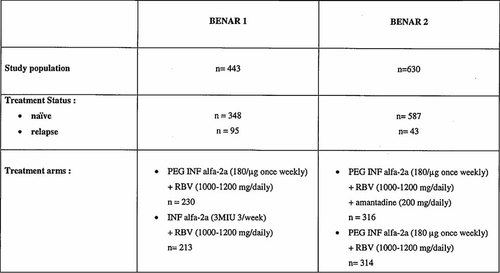

In order to compare the efficacy of antiviral therapy on HCV-5 with other genotypes, a meta-analysis of two large phase III/IV prospective randomized clinical trials conducted in Belgium in chronic hepatitis C naïve patients and relapsers (BERNAR 1 and BERNAR 2) has been performed [Langlet et al., 2009; Nevens et al., 2010]. The designs of both studies are summarized in Figure 1. For the meta-analysis the statistician had direct access to the individual patient data.

The designs of the BENAR 1 and BENAR 2 trials which assessed the response rate of pegylated interferon alpha-2a and ribavirin in patients with chronic hepatitis C in Belgium.

Both studies were conducted in full compliance with Good Clinical Practice standards with applicable Belgian laws and with the principles laid down in the revised version of the Declaration of Helsinki as reflected in an a priori approval by the institution's human research committee. As per protocol, informed consent was obtained from each patient after adequate explanation of the methods, objectives, and potential hazards of the study had been fully explained. The meta-analysis of the HCV-5 subgroup of patients was planned by protocol and a specific statistical analytical plan was issued prior to any analysis.

Both studies were designed to evaluate the safety and efficacy of pegylated interferon alpha and ribavirin therapy in a large population of patients with chronic hepatitis C. In both studies, the backbone therapy consisted of pegylated interferon alpha-2a (180 µg/week by sc route) and ribavirin (RBV) (1,000–1,200 mg po daily according to HCV genotype and body weight). Patients were treated for 24 (genotypes 2 and 3) or 48 (genotypes 1, 4, 5, and 6) weeks according to HCV genotype, according to internationally recommended practices [Fried et al., 2002]. The definitions of the endpoints were similar in both studies and also the inclusion and exclusion criteria were similar. International accepted rules for dose adaptation and interruption of treatment were used [Fried et al., 2002]. HCV RNA was measured in both studies with the AMPLICOR HCV MONITOR test V2.0.

The meta-analysis compared patient baseline characteristics, early virological response, response at 24 and 48 weeks of treatment, end-of-treatment response, sustained virological response, and relapse rate between, respectively, HCV-5 and HCV-1, and HCV-5, and HCV-2/3. For the purposes of consistency, only patients treated with pegylated interferon alpha-2a plus ribavirin (PEG-IFN + RBV) in both studies were included in the analysis of response to treatment. Since many amantadine HCV studies, including our BENAR 2 study and a recent meta-analysis showed that there was no effect of adding this drug, also patients who received amantadine together with PEG-INF + RBV were included in the analysis [Deltenre et al., 2004; Langlet et al., 2009]. The meta-analysis was done on the patient group who received at least one dose of study medication.

In addition, a subset of patients infected with HCV-1 selected from the studies databases to match the HCV-5 sample according to age category (< vs. ≥40), gender, baseline viral load (< vs. ≥800,000 IU/ml), cirrhosis (yes vs. no), pretreatment status (naïve vs. relapsers), and treatment received was compared to the HCV-5 patients. As in the previous analyses only patients treated PEG-IFN + RBV were selected.

Statistical Analysis

Categorical variables were compared using Fisher's exact test and continuous variables using Student's t-test. Stepwise logistic regression analyses were performed using a multivariate stepwise regression for end-of-treatment response, sustained virological response, and relapse rate. All statistical tests were performed at the 5% level of significance.

RESULTS

In total, 1,073 patients were recruited, from October 2000 to May 2005, in both studies of which 48 (4.5%) were of HCV-5 genotype. The distribution of genotypes of the patient population is given in Table I. The observed repartition of genotypes confirmed the predominance of genotypes 1, 2, and 3 but revealed a rather higher prevalence of HCV-5 in Belgium compared to other European countries and the USA.

| Study | All patients | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| BERNAR 1 | BERNAR 2 | Number | % | |||

| Number | % | Number | % | |||

| Genotype | ||||||

| 1 | 279 | 62.9 | 338 | 53.7 | 617 | 57.5 |

| 2 | 31 | 7.0 | 42 | 6.7 | 73 | 6.8 |

| 3 | 76 | 17.2 | 156 | 24.8 | 232 | 21.6 |

| 4 | 34 | 7.7 | 66 | 10.5 | 100 | 9.3 |

| 5 | 22 | 5.0 | 26 | 4.0 | 48 | 4.5 |

| 6 | 1 | 0.2 | 2 | 0.3 | 3 | 0.3 |

| Total | 443 | 100.00 | 630 | 100.00 | 1,073 | 100.00 |

Characteristics of the Patients

Main patient baseline characteristics are shown in Table II. HCV-5 patients are predominantly females from West Flanders. The mean age is 58 years, they are not infected by intravenous drug abuse and have more advanced liver disease. Among HCV-5, 60.4% of patients are female, compared to 32.8% in HCV-2/3 (P < 0.001). Mean ages in years are, respectively, 58.4 for HCV-5, 40.2 for HCV-2/3 (P < 0.001), and 47.3 for HCV-1 (P < 0.001). Cirrhosis was present in 27.7% of HCV-5 and in 15.1% of HCV-2/3, this difference is statistically significant (P = 0.037). The mode of HCV-5 acquisition is significantly different from both HCV-1 and HCV-2/3, most frequently this is unknown followed by transfusion. Only one single intravenous drug-associated case was identified suffering from HCV-5.

| Genotype | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 2/3 | 5 | |

| Geographic origin, n (%) | |||

| West Flanders | 61/617 (9.8%) | 34/305 (11.1%) | 32/48 (66.7%) |

| Gender, n (%) | |||

| Male | 329/617 (53.4%) | 205/305 (67.2%) | 19/48 (39.6%) |

| Female | 288/617 (46.6%) | 100/305 (32.8%) | 29/48 (60.4%) |

| Mean age, years | 47.3 | 40.2 | 58.1a |

| Caucasian, n (%) | 588/617 (95.3%) | 275/305 (90.2%) | 47/48 (97.9%) |

| Mean BMI (kg/m2) | 25.4 | 24.5 | 26.4 |

| Mode of HCV acquisition (%) | |||

| Unknown | 202/617 (32.7%) | 66/305 (21.6%) | 22/48 (45.8%) |

| Transfusion | 211/617 (34.2%) | 43/305 (14.1%) | 19/48 (39.6%) |

| Drug use | 142/617 (23.0%) | 166/305 (54.4%) | 1/48 (2.1%)a,b |

| Cirrhosis (%) | 113/617 (18.3%) | 46/305 (15.1%) | 13/48 (27.7%)c |

| Treatment status, n (%) | |||

| Naive | 528/617 (85.6%) | 276/305 (90.5%) | 44/48 (91.7%) |

| Relapsers | 89/617 (14.4%) | 29/305 (9.5%) | 4/48 (8.3%) |

| HCV ≥ 800,000 IU/ml, n (%) | 266/612 (43.5%) | 138/304 (45.4%) | 23/48 (47.9%) |

| ALT (%) | |||

| <2 ULN | 354/617 (57.4%) | 145/305 (47.6%) | 23/48 (47.9%) |

| 2 to <5 ULN | 226/617 (36.6%) | 114/305 (37.4%) | 22/48 (45.8%) |

| ≥5 ULN | 37/617 (6.0%) | 46/305 (15%) | 3/48 (6.3%) |

- ULN, upper limit of normality.

- a Genotype 5 versus 2/3: P < 0.001.

- b Genotype 5 versus 1: P < 0.001.

- c Genotype 5 versus 2/3: P < 0.037.

Response to Treatment

For this purpose only patients who received PEG-INF + RBV: genotype 1 patients n = 485, genotypes 2 and 3 n = 249, and genotype 5 n = 38. Treatment response is presented in Table III. Sustained virological response is 55.6% in HCV-5 which is very close to that seen in HCV-1 (50%) but lower, although not reaching statistical significance than in HCV-2/3 (75%). Early virological response (week 12) is lowest in HCV-5 (50%) and significantly different from that in HCV-2/3 (87.8%; P < 0.001). Response at end of treatment is also significantly lower in HCV-5 than in HCV-2/3.

| Genotype 1, n = 485 (%) | Genotype 2/3, n = 249 (%) | Genotype 5, n = 38 (%) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Virological response at week 12 | 65.9 | 87.8 | 50.0a |

| Virological response at week 24 | 71.4 | 81.8 | 66.7 |

| End of treatment response | 68.8 | 82.4 | 59.3a |

| Sustained virological response | 50.0 | 75.0 | 55.3a |

| Relapse Rate | 23.9 | 7.2 | 12.5 |

- a Genotype 5 versus 2/3: P < 0.001.

In the sample of matched patients, the “intrinsic sensitivity” of HCV-5 was shown to be identical to that of HCV-1 with a sustained virological response equal to 55.3% (21/38) in both matched groups (P = 1.000).

The multivariate analysis indicates that early virological response, genotype and HCV viral load at screening have a statistically significant impact on the rate of sustained virological response and that genotype, viral load at screening and treatment status (relapsers vs. naïve patients) are prognostic indicators of a sustained virological response.

DISCUSSION

The response rate to interferon-based therapy of patients infected with HCV-5 has been poorly documented and it has been suggested that HCV-5 patients respond better to therapy than HCV-1 patients [Legrand-Abravanel et al., 2004; Delwaide et al., 2005; Bonny et al., 2006]. However, this is based on retrospective data in small groups of patients treated with different kind of interferons with different dosages and treatment durations. This study is the first comparative analysis of HCV-5 response to pegylated interferon-based therapy derived from two large prospective randomized clinical trials. It has allowed better characterization of the Belgian HCV-5 population and the response to treatment in comparison to other genotypes.

Our HCV-5 population is characterized by a rather advanced age (58.4 years), a high frequency of cirrhosis (27.7%), a specific mode of HCV acquisition (mainly blood transfusion), and a particular geographic origin (66.7% of patients from West Flanders). This suggests that the infection in these patients occurred many years ago by blood transfusion in a specific region of Belgium. Genotype 5 is found frequently in South Africa. It was found that the Belgian and South African strains form two distinct clusters of similar diversity [Verbeeck et al., 2006].

In this study HCV-5 demonstrated a response to treatment similar to HCV-1 and a lower response to treatment compared to HCV-2/3. An analysis of matched patients demonstrates further that the HCV-5 “intrinsic sensitivity” to PEG-IFN + RBV combined therapy is indeed identical to HCV-1.

Therefore, in contrast to previous published studies, this meta-analysis suggests that HCV-5 patient response to treatment is more similar to that seen with HCV-1 than to HCV-2/3 and, that HCV-5 patients should probably be treated with the same antiviral therapy regimen as HCV-1 patients.