Clinical course and predictive factors of virological response in long-term lamivudine plus adefovir dipivoxil combination therapy for lamivudine-resistant chronic hepatitis B patients†

Mashu Aizawa and Akihito Tsubota contributed equally to this work.

Abstract

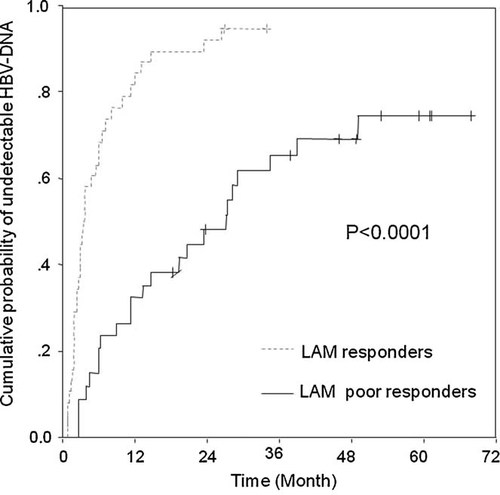

The aims of this study were to assess the long-term efficacy of lamivudine (LAM) plus adefovir dipivoxil (ADV) combination therapy in patients with chronic hepatitis B resistant to LAM, to identify predictive factors of complete viral response (HBV-DNA <2.6 log copies/ml at 12 months of combination therapy), and to analyze amino acid substitutions associated with treatment resistance in the hepatitis B virus (HBV) genome. Seventy-two patients who received ADV in addition to LAM for breakthrough hepatitis were enrolled. Undetectable HBV-DNA was observed in 61%, 74%, 81%, 84%, and 85% at 12, 24, 36, 48, and 60 months of combination therapy, respectively. On multivariate analysis, undetectable HBV-DNA during the preceding LAM monotherapy (P < 0.0001), alanine aminotransferase value ≥ the upper limit of normal × 6 (P = 0.006) and HBV-DNA level < 6.0 log copies/ml at the initiation of combination therapy (P = 0.007) were independent significant predictors of complete viral response. The cumulative rate of undetectable HBV-DNA was significantly higher in patients with response to the preceding LAM monotherapy than in those with poor response to it. Breakthrough hepatitis occurred in three patients without complete viral response and with poor response to the preceding LAM monotherapy, and rtA181A/V substitution was detected in one of the three patients. In conclusion, undetectable HBV-DNA during the LAM monotherapy was the strongest independent predictor of complete viral response to the following combination therapy. The efficacy of LAM plus ADV combination therapy may be determined by viral response to the preceding LAM monotherapy. J. Med. Virol. 83:953–961, 2011. © 2011 Wiley-Liss, Inc.

INTRODUCTION

Chronic hepatitis B affects as many as 350–400 million people worldwide and 1.5 million people in Japan, remains an important public health problem and a leading cause of liver-related morbidity and mortality [Kane, 1995; Lee, 1997]. Nucleos(t)ide analogues, such as lamivudine (LAM), adefovir dipivoxil (ADV) and entecavir (ETV), improve serum alanine aminotransferase (ALT) levels and liver histological findings by potent suppression of hepatitis B virus (HBV) replication [Nevens et al., 1997; Lai et al., 1998, 2002; Suzuki et al., 1999; Hadziyannis et al., 2003; Marcellin et al., 2003], and thus have been approved as therapeutic agents against chronic hepatitis B. Consequently, clinical manifestations of chronic hepatitis B patients would be improved significantly for a long-term period. However, prolonged treatments of nucleos(t)ide analogues increase the risk of emergence of drug-resistant HBV mutants.

LAM was the first oral therapeutic agent approved for the treatment of chronic hepatitis B and has a well-established safety and efficacy profile [Lai et al., 1998; Dienstag et al., 1999]. However, LAM causes resistant mutation at a high rate in the YMDD (tyrosine–methionine–aspartate–aspartate) motif of the HBV-DNA polymerase domain [Allen et al., 1998]. LAM-resistant mutants were reported to develop in 16–32% at 1 year, and 70% at 4 years of LAM monotherapy [Lok et al., 2003]. Therefore, most of patients with chronic hepatitis B with LAM-resistant mutants develop virological and biochemical breakthroughs, and may result in hepatic decompensation.

ADV is a nucleotide analog that possesses a potent antiviral activity against chronic hepatitis B resistant to LAM and wild-type chronic hepatitis B [Hadziyannis et al., 2003; Marcellin et al., 2003; Schiff et al., 2003; Perrillo et al., 2004; Peters et al., 2004]. ADV monotherapy was also reported to increase the risk of emergence of ADV-resistant mutants in patients resistant to LAM, with the rates of 21% at 15–18 months and 22% at 24 months after ADV monotherapy [Fung et al., 2006; Rapti et al., 2007]. On the other hand, combination therapy with ADV plus LAM was reported to reduce the rate of emergence of ADV-resistant mutations in patients resistant to LAM [Fung et al., 2006; Rapti et al., 2007]. A previous open-label study in HBeAg negative patients resistant to LAM demonstrated that combination therapy did not result in the development of ADV resistance over a period of 3 years, and that the rate of undetectability of serum HBV-DNA was higher than ADV monotherapy [Rapti et al., 2007]. However, some patients resistant to LAM show poor response to LAM plus ADV combination therapy, and a few studies reported the emergence of HBV mutations associated with resistance to LAM and ADV (rtA181T/V, rtN236T) [Perrillo et al., 2004; Lee et al., 2006; Yatsuji et al., 2008]. The emergence of these HBV mutations would be a critical issue in patients with chronic hepatitis B who receive LAM plus ADV combination therapy.

The aims of this study were: (1) to assess the long-term efficacy of LAM plus ADV combination therapy in patients with chronic hepatitis B resistant to LAM; (2) to identify predictive factors of complete viral response to combination therapy; and (3) to analyze amino acid substitutions associated with treatment resistance in HBV genome.

METHODS

Patients

Since January 2001, 195 adult Japanese patients with chronic hepatitis B received LAM monotherapy at Department of Gastroenterology and Hepatology, Kashiwa Hospital and Jikei University Hospital, Jikei University School of Medicine. Of the 195 patients, 98 received ADV in addition to ongoing LAM (“combination therapy”) due to breakthrough hepatitis, which was defined as re-elevation of serum ALT levels greater than the upper limit of normal (ULN, 35 IU/L) following the development of virological breakthrough (defined as >1 log copies/ml increase of serum HBV-DNA from the nadir level). Of the 98 patients eligible for participation in this study, 26 were excluded, because 12 were started LAM therapy at the other hospitals, 5 moved in the other prefectures after the initiation of combination therapy and 9 satisfied the exclusion criteria. Data from the 72 patients who received LAM plus ADV combination therapy were subjected to this analysis. All of the patients were positive for hepatitis B surface antigen (HBsAg) and serum HBV-DNA, and had elevated serum ALT levels for more than 6 months before treatment. None of the patients had been treated with any other nucleos(t)ide analogs, such as ETV. They continued to receive the combination therapy for more than 12 months. The exclusion criteria were as follows: positive for hepatitis C virus antibody, decompensated cirrhosis, evidence of other liver diseases, such as alcoholic liver disease, drug-induced liver disease, or autoimmune hepatitis, and poor compliance with LAM monotherapy. This study was conducted in accordance with The Code of Ethics of the World Medical Association (Declaration of Helsinki). The local ethics committee of The Jikei University School of Medicine approved the study. All patients provided their written informed consent.

Treatment

In all of the 72 patients, LAM was administrated orally 100 mg once a day, and then ADV (10 mg once a day) was added to LAM after the development of breakthrough hepatitis. All patients were followed-up every 4–12 weeks during combination therapy, and assessed for clinical and laboratory data and HBV-related markers (hepatitis B e antigen; HBeAg, antibody against HBeAg; anti-HBe, and HBV-DNA). Adverse effects were monitored by careful interview and medical examination throughout the study. Patient compliance with treatment was evaluated by a questionnaire and medical records and by counting the number of returned capsules. The diagnosis of cirrhosis was based on liver biopsy and/or on imaging modality, such as deformity of liver and atrophic liver right lobe/elongated left lobe. Treatment efficacy was evaluated by viral response, determined by undetectable of serum HBV-DNA level (<2.6 log copies/ml) after combination therapy, and ALT normalization after the initiation of LAM plus ADV combination therapy. HBeAg loss and seroconversion were measured for the secondary evaluation of treatment response. Complete viral response was defined as viral response at 12 months of combination therapy.

Serum Assays

Serum HBsAg, HBeAg, and anti-HBe were determined by using commercially available enzyme immunoassay (EIA) kits (Abbott Japan, Tokyo, Japan). Serum HBV-DNA level was determined using transcription-mediated amplification assay method (TMA; Chugai Pharmaceutical, Tokyo, Japan: detection range, 3.7–8.7 log genome equivalent; LGE/ml) [Kamisango et al., 1999]. If serum HBV-DNA levels decreased to <3.7 LGE/ml during follow-up, a method of measurement was changed to Amplicor HBV monitor test (Roche Diagnostics, Tokyo, Japan: detection range, 2.6–7.6 log copies/ml). The HBV genotype was determined by using an HBV genotype enzyme immunosorbent assay (Institute of Immunology, Tokyo, Japan) [Usuda et al., 1999]. The measurement of YMDD mutations was performed by using the enzyme-linked mini-sequence assay (PCR-ELMA; Genome Science, Tokyo, Japan).

DNA Extraction and Direct Sequencing Analysis

The amino acid substitutions associated with ADV resistance were assessed in patients with chronic hepatitis B who developed virological breakthrough after the initiation of combination therapy. HBV-DNA was extracted from sera by using the Smitest EX-R&D kit (Genome Science). The polymerase and surface regions of the HBV genome were amplified specifically by using GeneAmp High Fidelity Polymerase chain reaction (PCR) System (Applied Biosystem, Inc., Foster City, CA). The PCR conditions were performed as follows: 94°C for 1 min; 54°C for 1 min; and 68°C for 3 min; 35 cycles, followed by a final elongation of 10 min at 68°C. All of the necessary precautions to prevent cross-contamination were observed, and negative controls were included in each assay. The nucleotide sequences of the PCR products were determined by direct sequencing method. Translation into deduced amino acid sequences and alignments were done by using DNASIS software packages (Hitachi Software, Tokyo, Japan). The references of HBV genome in patients with chronic hepatitis B were used from DDBJ/EMBL/Genbank databases registered [Okamoto et al., 1988].

Statistical Analysis

Non-parametric tests including Fisher's exact probability test, χ2 test and Mann–Whitney U-test were used to compare patient characteristics, as appropriate. The cumulative rate of undetectable HBV-DNA was calculated using the Kaplan–Meier method and differences between the curves were tested using the log-rank test. To investigate the factors associated with complete viral response, univariate analyses were conducted using logistic regression analysis, and all factors found to be at least marginally in relation to complete viral response (P < 0.10) were tested by multivariate analysis using a stepwise logistic regression model. P-values of <0.05 were considered statistically significant. All data were analyzed using the SPSS 17.0 statistical package (SPSS, Chicago, IL).

RESULTS

Patient Characteristics at the Initiation of LAM Plus ADV Combination Therapy

Patient characteristics at the initiation of LAM plus ADV combination therapy are shown in Table I. HBV genotype was examined for 46 patients: 44 were infected with genotype C, and the remaining two with genotype A and B, respectively. Twenty-three patients (32%) had compensated cirrhosis. YMDD mutations were assayed in 46 patients before the addition of ADV to ongoing LAM therapy. The rate of YIDD, YVDD, and mixed type was 48%, 24%, and 28%, respectively. Patient compliance with combination therapy was excellent.

| At the initiation of LAM monotherapy (n = 72) | At the initiation of LAM plus ADV combination therapy (n = 72) | |

|---|---|---|

| Gender (male/female) | 59/13 | 59/13 |

| Age (years)a | 48 (21–65) | 51 (23–67) |

| HBeAg positive, n (%) | 41 (57) | 38 (53) |

| HBV-DNA (log copies/ml)a | 6.9 (3–8.8) | 7.0 (3.4–8.8) |

| HBV genotype, n | ||

| A | 1 | 1 |

| B | 1 | 1 |

| C | 44 | 44 |

| YMDD mutation, n (%) | ||

| YVDD | — | 22 (48) |

| YIDD | — | 11 (24) |

| V/I | — | 13 (28) |

| Total bilirubin (mg/dl)a | 0.8 (0.4–1.8) | 0.8 (0.3–3.1) |

| AST (IU/L)a | 65 (19–407) | 73 (21–1,091) |

| ALT (IU/L)a | 97 (21–781) | 110 (19–1,945) |

| Albumin (g/dl)a | 4.2 (2.9–5) | 4.3 (3.2–5.0) |

| Alpha-fetoprotein (µg/L)a | 6 (0.6–201) | 5 (2–1,353) |

| Platelet count (×104/mm3)a | 13.8 (4.5–28.2) | 14.0 (3.6–25.8) |

| Liver cirrhosis, n (%) | 23 (32) | 23 (32) |

- a Median (range).

Outcome of LAM Plus ADV Combination Therapy

The median follow-up period was 78 months (range, 32–114 months) after the initiation of LAM monotherapy, and 46 months (range, 21–80 months) after the initiation of combination therapy. Viral response was observed in 61% (44/72), 74% (52/70), 81% (48/59), 84% (38/45), and 85% (23/27) at 12, 24, 36, 48, and 60 months of combination therapy, respectively. Thus, 44 patients achieved complete viral response. ALT normalization was observed in 67% (48/72), 83% (58/70), 92% (54/59), 82% (37/45), and 89% (24/27), respectively (Table II). In 11 of 38 HBeAg-positive patients, HBeAg loss occurred after combination therapy. Seven of the 11 patients showed HBeAg loss within 12 months of combination therapy.

| Time (month) after LAM plus ADV combination therapy | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 12 | 24 | 36 | 48 | 60 | |

| All patients (n = 72) | n = 72 | n = 70 | n = 59 | n = 45 | n = 27 |

| Viral response, n (%)a | 44 (61) | 52 (74) | 48 (81) | 38 (84) | 23 (85) |

| ALT normalization, n (%)b | 48 (67) | 58 (83) | 54 (92) | 37 (82) | 24 (89) |

| Virological breakthrough, n (%) | 0 (0) | 1 (1) | 2 (3) | 3 (7) | 3 (11) |

| Patients with complete viral response (n = 44) | n = 44 | n = 44 | n = 35 | n = 25 | n = 15 |

| Viral response, n (%)a | 44 (100) | 44 (100) | 35 (100) | 25 (100) | 15 (100) |

| ALT normalization, n (%)b | 34 (77) | 36 (82) | 31 (89) | 22 (88) | 15 (100) |

| Virological breakthrough, n (%) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) |

| Patients without complete viral response (n = 28) | n = 28 | n = 26 | n = 24 | n = 20 | n = 12 |

| Viral response, n (%)a | 0 (0) | 8 (31) | 15 (63) | 13 (65) | 8 (67) |

| ALT normalization, n (%)b | 14 (50) | 22 (85) | 23 (96) | 15 (62) | 9 (75) |

| Virological breakthrough, n (%) | 0 (0) | 1 (4) | 2 (8) | 3 (15) | 3 (25) |

- a HBV-DNA < 2.6 log copies/ml.

- b ALT < 35 IU/L.

All of the 44 patients with complete viral response and sustained viral response and ALT normalization throughout the entire follow-up period. By contrast, in 28 patients who did not achieve complete viral response at 12 months, the rate of viral response was 31% (8/26), 63% (15/24), 65% (13/20), and 67% (8/12) at 24, 36, 48, and 60 months of combination therapy, respectively (Table II). In three patients without complete viral response, their HBV-DNA levels increased again (virological breakthrough) at 20, 31, and 46 months of combination therapy, and subsequently breakthrough hepatitis developed. The maximum of ALT flare was 74, 92, and 172 IU/L, respectively. Although the fluctuation of serum ALT level was continued, severe hepatitis or hepatic failure did not occur during follow-up in the three patients.

None of 23 patients with cirrhosis progressed to decompensation or hepatic failure. However, three cirrhotic patients developed hepatocellular carcinoma, and were treated with transcatheter arterial chemoembolization and/or percutaneous ethanol injection. All the three patients are alive.

Factors Predictive of Complete Viral Response to LAM Plus ADV Combination Therapy

Univariate analysis showed that the following variables were significantly associated with complete viral response: patient age <40 years (P = 0.049), undetectable HBV-DNA (P < 0.001), and ALT normalization (P = 0.030) during the preceding LAM monotherapy, duration time between the initiation of LAM monotherapy and biochemical breakthrough <1.5 years (P = 0.062)/virological breakthrough <1 year (P = 0.016), and ALT level ≥ULN × 6 (P = 0.044), HBeAg negative (P = 0.006), and HBV-DNA level <6.0 log copies/ml (P = 0.004) at the initiation of combination therapy.

Multivariate analysis was performed subsequently, because some of these variables were correlated mutually. In the final step, multivariate analysis identified the following variables as significantly independent predictors of complete viral response: undetectable HBV-DNA during LAM monotherapy [odds ratio (OR): 13.44, 95% confidence interval (CI): 3.33–54.15, P < 0.001], and ALT level ≥ ULN × 6 (OR: 10.38, 95% CI: 1.95–55.24, P = 0.006) and HBV DNA level <6.0 log copies/ml at the initiation of combination therapy (OR: 11.74, 95% CI: 1.94–71.08, P = 0.007) (Table III).

| Factors | Category | Odds ratio | 95% CI | P |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| HBV-DNA undetectable during LAM monotherapy | 1: Absence | |||

| 2: Presence | 13.44 | 3.33–54.15 | <0.001 | |

| ALT (IU/L) at baselinea | 1: <ULN × 6b | |||

| 2: ULN × ≥6b | 10.38 | 1.95–55.24 | 0.006 | |

| HBV-DNA (log copies/ml) at baseline a | 1: <6.0 | 11.74 | 1.94–71.08 | 0.007 |

| 2: ≥6.0 |

- CI, confidence interval.

- a Baseline; the initiation of LAM plus ADV combination therapy.

- b Upper limit of normal; 35 IU/L.

Comparison of Viral Response to Combination Therapy Between LAM Responder and LAM Poor Responder

Seventy-two patients were categorized into 34 LAM responders in whom HBV viremia disappeared at least once during the preceding LAM monotherapy and 38 LAM poor responders in whom HBV viremia persisted. The cumulative rate curves of undetectable HBV-DNA after combination therapy are shown in Figure 1. The cumulative rates were significantly higher in LAM responders than those in LAM poor responders (P < 0.0001). Subsequently, the association of viral response to combination therapy with HBV-DNA and ALT levels at the initiation of combination therapy was investigated (Table IV). Approximately 80% of the LAM responders decreased serum HBV-DNA to undetectable within 24 months of combination therapy, despite of unfavorable factors (HBV-DNA level ≥ 6.0 log copies/ml and ALT level < ULN × 6). Significant differences between the two groups were shown at 6 and 12 months of combination therapy.

Cumulative probability of undetectable HBV-DNA during LAM plus ADV combination therapy in the CHB patients showed LAM response or LAM poor response. LAM responder: HBV viremia once cleared during preceding LAM monotherapy. LAAM poor responder: HBV viremia persisted during preceding LAM monotherapy.

| Time (month) after LAM plus ADV combination therapy | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0 | 6 | 12 | 24 | 36 | 48 | 60 | |

| HBV-DNA ≥ 6 log copies/ml and ALT < 210 IU/L | |||||||

| LAM responders, n (%) | 0/11 (0) | 5/11 (45) | 6/11 (55) | 9/11 (82) | 8/9 (88) | 6/6 (100) | 4/4 (100) |

| LAM poor responders, n (%) | 0/22 (0) | 2/22 (9) | *4/22 (18) | *9/20 (45) | 13/19 (68) | 12/17 (71) | 8/11 (72) |

- * P < 0.05.

Amino Acid Substitutions in Polymerase and Surface Region of HBV Genome in Patients With Virological Breakthrough

To examine the relation between development of HBV mutations and virological breakthrough after combination therapy, amino acid substitutions in polymerase/transcriptase (Pol/RT) and surface regions of the HBV gene were analyzed in three patients resistant to LAM who developed breakthrough hepatitis after combination therapy (Table V). The three patients were HBeAg positive and showed ALT level < ULN × 6 at the initiation of combination therapy and poor response to the preceding LAM monotherapy. Cases 1 and 3 had HBV-DNA >6 log copies/ml at the initiation of combination therapy.

| Pol/RT | Surface | ||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Codon | 80 | 169 | 173 | 180 | 181 | 184 | 200 | 202 | 204 | 233 | 236 | 250 | 164 | 173 | 192 | 195 | 196 |

| Reference sequencea | L | I | V | L | A | T | A | S | M | I | N | M | E | L | L | I | W |

| Case 1 | |||||||||||||||||

| Pre-LAM | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — |

| Pre-ADV | — | — | — | M | — | — | V | — | I | — | — | — | — | — | F | — | L |

| 20 months of ADV | — | — | — | M | — | — | V | — | I | — | — | — | — | — | F | — | L |

| 52 months of ADV | — | — | — | M | A/V | — | V | — | — | — | — | — | — | L/F | F | I/M | W/L |

| Case 2 | |||||||||||||||||

| 48 months of ADV | — | — | L | L/M | — | — | — | — | I | — | — | — | D | — | — | — | L |

| Case 3 | |||||||||||||||||

| 55 months of ADV | — | — | — | M | — | — | — | — | V | — | — | — | — | — | — | M | — |

- a References of whole HBV genome were used previous sequences date of DDBJ/EMBL/Genbank databases.

Amino acid substitutions associated with both LAM resistance (rtL80, rtV173, rtL180, rtM204) and ADV resistance (rtA181, rtI233, rtN236) were detected in case 1 (rtL180M + rtA181A/V). The remaining two patients showed only LAM-resistant mutations: rtV173L + rtL180L/M + rtM204I in case 2 and rtL180M + rtM204V in case 3. There was no amino acid substitutions associated with ETV resistance (rtI169, rtT184, rtS202, rtM250) in all the three patients.

Therefore, amino acid substitutions of Pol/RT and surface regions in case 1 were analyzed sequentially (Table V) at the initiation of LAM monotherapy, at the initiation of combination therapy, at the development of virological breakthrough (20 months of combination therapy) and at the subsequent development of breakthrough hepatitis (52 months of combination therapy). The substitution rtM204I emerged when breakthrough hepatitis occurred during the preceding LAM monotherapy, and was replaced by wild type at the emergence of rtA181A/V (52 months of combination therapy). The substitution rtA181A/V was undetectable at the virological breakthrough (20 months of combination therapy), but detectable at the subsequent breakthrough hepatitis (52 months of combination therapy). The other amino acid substitution in the Pol/RT region was rtA200V that emerged in case 1. In the surface region overlapped with Pol/RT region, some amino acid substitutions were detected: rtA181A/V and sL173L/F, rtA200V and sL192F in case 1, rtV173L and sE164D in case 2, rtM204I and sW196L in cases 1 and 2, and rtM204V and sI195M in case 3.

DISCUSSION

The present study was conducted to assess the long-term anti-viral effects of LAM plus ADV combination therapy on chronic hepatitis B resistant to LAM and to clarify factors that influenced viral response to the combination therapy. Univariate and multivariate analyses indicated that low HBV-DNA and high ALT levels at the initiation of combination therapy were independent factors associated with complete viral response in patients resistant to LAM. Interestingly, undetectable HBV-DNA during the preceding LAM monotherapy was the strongest influencing factor (Table III). In patients with undetectable HBV-DNA during the preceding monotherapy, serum HBV-DNA was eliminated earlier after the initiation of combination therapy compared to those with persistent HBV viremia. The cumulative rates and curves of undetectable HBV-DNA showed apparent difference between the two patient groups (P < 0.0001, Fig. 1). Despite high HBV-DNA and low ALT levels at the initiation of combination therapy, such patients with favorable viral response to the preceding monotherapy showed satisfactory response to the following combination therapy. By contrast, in patients who showed persistence of HBV viremia during the preceding monotherapy, viremia was likely to persist during the following combination therapy. It is noteworthy that viral response to the preceding LAM monotherapy would determine the long-term outcome of the following LAM plus ADV combination therapy even after the emergence of LAM-resistant mutants. Predictive factors of viral response to ADV treatment in patients resistant to LAM have been reported to be female gender, lower HBV-DNA, higher ALT, negative HBeAg at the initiation of ADV therapy, and rapid HBV-DNA decline after ADV therapy [Lampertico et al., 2005; Fung et al., 2006; Buti et al., 2007; Hosaka et al., 2007; Rapti et al., 2007; Yatsuji et al., 2008; Hass et al., 2009]. Most of these factors were measured at the initiation of ADV therapy or after the treatment. There are few reports that explored the association of variables at the initiation of the preceding LAM monotherapy or during the monotherapy with the following outcome of LAM plus ADV combination therapy. To our knowledge, this is the first study that investigated the correlation between the response to the preceding LAM monotherapy and the following LAM plus ADV combination therapy. These novel findings might provide us important information and clues to treat patients with nucleotide analogues and to understand the underlying mechanism of treatment sensitivity or resistance.

Several studies reported that rtA181S substitution was detected at the initiation of combination therapy in patients with poor response to ADV and associated with the lack of viral response at 6 and 24 months of treatment [Moriconi et al., 2007; Yatsuji et al., 2008]. In the present study, one patient (case 1) developed rtA181A/V substitution during the long-term combination therapy. However, the substitution was detected after the breakthrough hepatitis during combination therapy, but not at the initiation of combination therapy. There were no HBV mutations associated with ADV resistance in the remaining two patients with breakthrough hepatitis and two patients without complete viral response (date not shown). Therefore, unfavorable treatment outcome of combination therapy appears not to depend exclusively on ADV-resistant mutations.

Several studies investigated the relation between mutation patterns resistant to LAM and response to ADV treatment. One study reported that the decline of HBV-DNA level was greater in patients with rtM204I than those with rtM204V [Suzuki et al., 2006]. However, another study suggested that mutations resistant to LAM, such as rtM204I, rtM204V, rtL180M, rtL80I, and rtV173L, did not influence the early antiviral effect of ADV monotherapy [Cha et al., 2009]. Thus, there is no consensus concerning common resistant mutants against ADV-rescue therapy. Amino acid substitutions alone do not elucidate completely the reason why patients with poor response to the preceding LAM monotherapy responded poorly to combination therapy. An alternative explanation for this issue may be related to the low potency of 10 mg daily dose of ADV. Previously, efficacy and safety of ADV 20 mg daily in patients resistant to LAM and with persistent viremia during the preceding ADV 10 mg daily were reported [Hezode et al., 2007]. Although increments in dose of ADV might be beneficial strategy for achievement of complete viral response, it is not recommended because of drug safety [Marcellin et al., 2003].

In the present study, the emergence of rtA181A/V substitution was accompanied with reversion of rtM204 at breakthrough hepatitis after combination therapy. Clonal HBV genome analyses reported the dynamic changes of major variants in HBV quasispecies throughout sequential therapy with nucleos(t)ide analogues [Yim et al., 2006; Ji et al., 2009; Zaaijer et al., 2009]. The selection of viral variants in quasispecies might be essential to the survival of HBV. In clinical and in vitro study, the rtA181T/V mutation reduced the susceptibility not only to LAM, but also to ADV [Qi et al., 2006; Villet et al., 2008]. In the present study, the proportion of rtM204I mutation in HBV quasispecies decreased gradually, while the proportion of rtA181V mutation increased and eventually became dominant.

A recent study, in which Japanese patients resistant to LAM were treated with LAM plus ADV combination therapy for median 28 months, reported that the rate of viral response was 69% at 12 months, 81% at 24 months, and 87% at 36 months [Yatsuji et al., 2008]. The rate of viral response in this study (median follow-up period, 44 months) was 61%, 74%, and 81%, respectively, indicating that two results were similar. Of note, the rate of viral response was maintained even after 60 months of combination therapy in 85% (23/27) of the present patients, all of whom sustained viral response and did not develop breakthrough hepatitis during the follow-up periods. Thus, the efficacy of combination therapy lasted for long-term periods in patients resistant to LAM. In contrast, the rate of viral response was only 67% (8/12) at 60 months of combination therapy in patients without complete viral response. Furthermore, breakthrough hepatitis occurred in 3 patients without complete viral response alone, who had HBV viremia persistently throughout the preceding LAM monotherapy. The rate of development of breakthrough hepatitis was relatively high as compared to that reported in previous studies [Peters et al., 2004; Lampertico et al., 2007; Rapti et al., 2007]. One study reported that none of 145 patients resistant to LAM developed virological breakthrough during 4 years of LAM plus ADV combination therapy, whereas the cumulative emergence rate of rtA181T was 4% at 4 years [Lampertico et al., 2007]. These differences among several reports might be caused by the baseline characteristics; the rate of HBe-Ag positive and HBV-DNA level in our study were higher than those in the previous study (53% vs. 24% and 7.0 log copies/ml vs. 6.0 log copies/ml, respectively). Most of patients in this study were infected with HBV genotype C, while genotypes in a previous study were D. On the other hand, another study from Japan reported that ADV-resistance mutants rtA181S and rtA181T/rtN236T were detected in 2 of 129 patients resistant to LAM treated with combination therapy, and that breakthrough hepatitis occurred in one patient [Yatsuji et al., 2008]. Similar to this study, HBV viremia persisted throughout the preceding LAM monotherapy and the following combination therapy in the patient with breakthrough hepatitis. Previous reports suggested that persistent viral replication during treatment of nucleos(t)ide analogues facilitates the occurrence of substitutions in Pol/RT region of the HBV genome [Hadziyannis et al., 2006; Rapti et al., 2007]. As described in this study, persistence of HBV viremia throughout the preceding LAM monotherapy might increase the risk of development of HBV mutations and breakthrough hepatitis. To reduce the risk by decreasing HBV viremia to undetectable level, alteration of treatment strategy (e.g., addition of or switching to another nucleos(t)ide analogue) would be important.

The antiviral efficacy and safety of tenofovir disoproxil fumarate (TDF) have been reported in patients with resistance to different nucleos(t)ide analogues treatment including combination of LAM with ADV [van Bommel et al., 2006; Tan et al., 2008]. Its effect on complete viral suppression was independent of viral load at the switching to TDF monotherapy, except for patients with ADV genotypic resistance. Thus, switching to TDF monotherapy may be better for patients with treatment failure of LAM monotherapy, especially when resistance to the following ADV could be foreseen. However, TDF has been licensed in 2008 for the treatment of HBV infection only in the United States and the Europe. LAM monotherapy is still prescribed for treatment-naïve patients in many countries, and management of HBV resistant to LAM is one of critical issues even now. ADV is still key drug to rescue patients with treatment failure of LAM.

In conclusion, undetectable level of serum HBV-DNA during the preceding LAM monotherapy was associated most strongly with complete viral response to the following LAM plus ADV combination therapy in patients with chronic hepatitis B resistant to LAM. In patients who did not achieve complete viral response, HBV viremia persisted during the preceding LAM monotherapy and breakthrough hepatitis occurred during the following LAM plus ADV combination therapy. Careful and close monitoring of patients resistant to LAM is necessary even after combination therapy, specifically, in patients with persistent HBV viremia during the preceding LAM monotherapy.