Full genome characterization of hepatitis B virus strains from blood donors in Iran

Abstract

Iran is a low to medium endemic country for hepatitis B virus (HBV), depending on the region, where genotype D is dominant. Samples from 170 asymptomatic HBsAg-positive blood donors were quantified and the median viral load was 6.7 × 102 IU/ml with 10.6% samples unquantifiable. Fifty complete genome sequences of these strains were characterized. Phylogenetic analysis identified 98% strains as subgenotype D1 and 2% as D2. Deduced serotypes were ayw2 (94%), ayw1 (4%), and adw (2%). The nucleotide diversity of the complete genome subgenotype D1 Iranian strains was limited (2.8%) and comparison with D1 strains from Egypt and Tunisia revealed little variation between strains from these three countries (range 1.9–2.8%). The molecular analysis of the individual genes revealed that the G1896A mutation was present in 86.2% of the strains and in 26 strains (29.9%) this mutation was accompanied by the G1899A mutation. The double mutations A1762T/G1764A and G1764T/C1766G were found in 20.7% and 24.1% of the strains, respectively. The pre-C initiation codon was mutated in five strains (5.8%). One strain had a 2-amino acid (aa) insertion at position s111 and another sP120Q substitution suggesting a vaccine escape mutant. J. Med. Virol. 83:948–952, 2011. © 2011 Wiley-Liss, Inc.

INTRODUCTION

The dominant hepatitis B virus (HBV) genotype in The Middle East and in Iran is genotype D [Alavian et al., 2007] and especially subgenotype D1 [Veazjalali et al., 2009]. Iran has medium endemicity of HBV [André, 2000; Alavian et al., 2007; Khedmat et al., 2007; Doosti et al., 2009; Kafi-Abad et al., 2009; Merat et al., 2009] and the recently reported prevalence of HBsAg and anti-HBc in the general population was 2.6% and 16.4%, respectively [Merat et al., 2009], although Kafi-Abad et al. [2009] reported an HBV prevalence of 0.8% among 1st time blood donors. Iran is a multiethnic country and its HBsAg levels differ from region to region [Doosti et al., 2009]. The implementation of infant vaccination since 1992 played an important role in the decrease of HBV prevalence [Alavian et al., 2007; Merat et al., 2009]. However, HBV remains the main cause of chronic liver disease and hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) in Iran [Alavian et al., 2007; Merat et al., 2009]. The identification and description of HBV mutations is of great importance because it could predict the outcome of the disease, for example, specific mutation on the X genes are associated with higher risk of HCC, mutations on the S gene with occult HBV, and mutations on basic core promoter/pre-core (BCP/PC) with lack of, or reduced production of the early HBV antigen.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

HBsAg-containing plasma samples (N = 170) were obtained from volunteer asymptomatic blood donors in Tehran, Iran. Screening of samples for HBV is routinely done in Iran and was performed as reported previously [Kafi-Abad et al., 2009]. Positive donors were excluded from further donations. Viral DNA was extracted from 500 µl of plasma using the Roche Total Nucleic Acid Isolation kit (Roche Diagnostics GmbH, Mannheim, Germany) according to the manufacturer's instructions. Viral DNA was quantified by Q-PCR using a TaqMan-based methodology and the Mx3000 or Mx4000 Multiplex Quantitative PCR Systems (Stratagene, La Jolla, CA) as described previously [Allain et al., 2003]. A secondary in-house internal control calibrated regularly against the WHO International Standard for HBV DNA for nucleic acid testing (NAT) assays 97/746 (National Institute for Biological Standards and Controls [NIBSC], Potters Bar, UK) was used as standard.

To obtain complete nucleotide sequences of HVB genome, a nested PCR using the Expand High Fidelity PCR system (Roche) amplifying a product of approximately 3,000 bp (base pairs) was used as reported previously [Zahn et al., 2008]. A semi-nested PCR targeting the BCP/PC region (276 bp) was used as described [Candotti et al., 2006]. It allowed to add the 50 bp not amplified with the nearly full-length primers.

Full-length and BCP/PC amplicons were purified with the E.Z.N.A.™ Cycle-Pure kit (Omega Bio-tek, Inc., Norcross, GA). Purified DNA was directly sequenced with the ABI Prism BigDye Terminator Cycle Sequencing Ready Reaction kit, version 1.0, and the ABI Prism 3100 Genetic Analyzer or the Applied Biosystems 3730xl DNA Analyzer (Applied Biosystems, Warrington, UK). A set of 6 sequencing primer pairs covering the whole HBV genome was used as previously described [Zahn et al., 2008].

Analysis of the produced electrophoregrams was done with the SeqMan Pro program from the Lasergene package version 7.1 (DNASTAR, Inc., Madison, WI). The consensus sequences of the full-length and BCP/PC regions were jointed with the MacVector software version 7.2 and the ClustalW alignment option. Translation of the four HBV genes was done with the SeqBuilder program of Lasergene package. Phylogenetic analysis was performed using PAUP* under the Neighbor-Joining algorithm based on Kimura-2-parameter distance estimation ignoring all positions with gaps in pairwise comparisons. Bootstrap values above 70% were considered as significant.

Full genome diversity between subgenotype D1 strains obtained from Iran (N = 49), Egypt (N = 29), and Tunisia (N = 15) and within the four genes of wild-type genotype D1 Iranian strains was calculated using PAUP* as described by Meldal et al. [2009]. Serotyping of the strains was predicted from the genome sequence according to Kramvis et al. [2005]. All complete genome sequences from Iran were submitted to GenBank under the accession numbers (GU456635–GU456684).

The statistical analysis of the data was performed with Microsoft® Excel® 2004 version 11.5.1 and PRISM version 4.0b (GraphPad Software, Inc., San Diego, CA). The non-parametric Mann–Whitney test was used to compare not distributed normally data and the Fisher's exact test was used for the analysis of contingency tables.

RESULTS

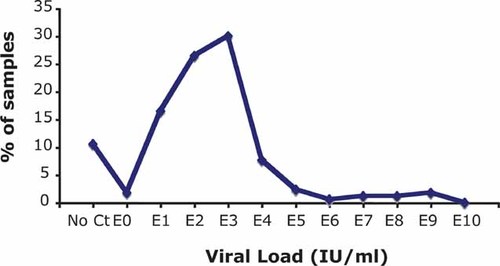

In total, 170 HBsAg+ samples from Tehran, Iran were processed. The age of donors ranged between 19 and 61 years with a median of 39.5 years. The majority of donors were male (91.2%). HBV DNA was quantified in 152/170 samples (89.4%) by Q-PCR and the median viral load was 6.7 × 102 IU/ml (range 0–5.1 × 109 IU/ml). The viral load distribution is shown in Figure 1. The majority of the samples carried viral load below 1 × 104 IU/ml. Samples that were Q-PCR-negative (No Ct) and HBsAg-positive were assumed to contain HBV DNA below the limit of detection of the assay (10 IU/ml).

HBV viral load distribution of 170 Iranian HBsAg+ blood donor samples. The majority of the samples carry viral load below 1 × 104 IU/ml. Viral load of 10.6% samples could not be quantified either because viral load was too low to be adequately quantified (<10 IU/ml) or did not give any signal (no Ct). The dashed line represents the limit of detection.

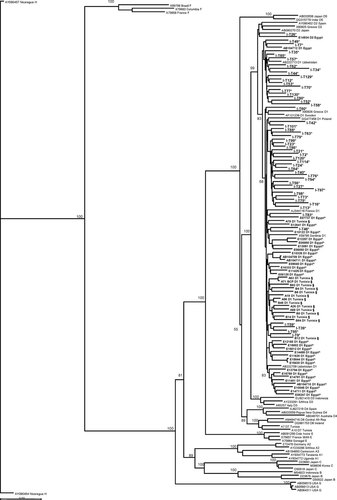

Complete HBV genome sequence was obtained for 50/67 (74.6%) samples selected at random. Full-length sequences were used for phylogenetic analysis and genotyping. Neighbor-Joining analysis determined that 49 strains were clearly clustered with subgenotype D1 (98%) and one (2%) with subgenotype D2 (Fig. 2). The majority of strains, 47/50 (94%), carried serotype ayw2. Two strains carried the deduced serotype ayw1 (4%) and one strain carried the serotype adw (2%). The genetic diversity of the strains was calculated and compared to two other groups of genotype D sequences from other South Mediterranean countries. The percentage of nucleotide (nt) divergence of D1 subgenotype strains from Iran, Egypt, and Tunisia are given in Table I. There was no more diversity within than between countries. It ranged between 1.9% and 2.8% and did not significantly differ between countries of origin.

Neighbor-Joining phylogenetic tree of HBV complete genome sequences from three countries where genotype D is dominant and other references. The sequence names of the three countries are in bold and the geographic origin of the samples is coded as asterisk (*) for Iran; circumflex accent (∧) for Egypt and section sign (§) for Tunisia. Bootstrap-support values obtained from 1,000 replicates are indicated. Accession number, origin and genotype/subgenotype are included in the code of the reference sequences. The accession numbers of the Tunisian sequences can be found in Meldal et al. [2009]. The 26 Egyptian sequences whose code name starts with E are unpublished. Bar corresponds to 0.02 substitutions per site.

| Country | N | Iran (%) | Egypt (%) | Tunisia (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Iran | 49 | 2.78 ± 1.88 | ||

| Egypt | 29 | 2.63 ± 1.64 | 2.18 ± 1.96 | |

| Tunisia | 15 | 2.61 ± 1.4 | 2.21 ± 0.3 | 1.87 ± 1.37 |

Molecular analyses were conducted on 87 BCP/PC sequences. Overall, 65 strains (74.7%) had one or more mutations at position(s) 1762/1764 or 1896 and 14 strains (16.1%) had triple mutations at positions 1762/1764/1896. The double A1762T/G1764A mutation was present in 18 strains (20.7%) and the double G1764T/C1766G mutation in 21 strains (24.1%). A premature stop codon related to the G1896A mutation was observed in 75/87 sequences (86.2%) and in 26 strains (29.9%) this mutation was accompanied by the G1899A mutation. The pre-C initiation codon was mutated in five strains (5.8%). The median amino acid (aa) divergence within the pre-C/C of 50 genotype D strains was 13% (range 2–26%).

Other genes were examined in terms of aa changes. In pre-S1, 3/50 strains (6%) had deletions. One strain (I/T70) presented a 3 aa deletion (positions ps5–7 aa) and a 21 aa deletion (positions ps59–79 aa), another strain (I/T58) had a 25 aa deletion (positions ps50–74 aa) and a 3 aa deletion (positions ps85–87 aa), and a third strain (I/T73) had a 14 aa deletion (positions ps50–63 aa). In pre-S2, 3/50 strains (6%) had deletions. One strain (I/T98) presented a 2 aa deletion (positions ps128–129 aa), another one (I/T23) had a 5 aa deletion (positions ps126–130 aa), and strain I/T58 had 10 aa deletion (positions ps121–130 aa). Strain I/T97 had 2 aa insertion in the a-determinant at position s111. The HBsAg concentration of this sample was 19 IU/ml and the viral load 3.6 × 103 IU/ml. There were three strains truncated of the last 11 aa (I/T56, I/T58, I/T73) of the S protein. The median overall aa divergence within the pre-S/S of 50 genotype D strains was 10% (range 0–36%). In the major hydrophilic region (MHR) the substitution rate was 0.4%. Only one sample (I/T97) had a sP120Q substitution suggesting a vaccine escape mutant. The median aa divergence within the polymerase of 50 genotype D strains was 27% (range 7–49%). There were five strains with deletions in the spacer domain corresponding to the pre-S1/S2 deletions.

The X gene sequence of 50 genotype D strains was examined. There were 12 strains (24%) with the xK130M substitution and 16 strains (32%) with the xV131I that have been associated with increased risk of developing HCC. In most strains, aa substitutions were single events. Twelve strains had coexisting substitutions of xK130M and xV131I. In 50 genotype D X proteins, the median aa divergence was 6% (range 0–13%).

DISCUSSION

The present study analyzed 50 complete HBV genome sequences from asymptomatic HBsAg+ Iranian blood donors. This selection of samples gives a more representative picture of the HBV prevalence in the general population than patient samples that would bias the results toward a specific disease/condition. Only five complete genome sequences from Iranian chronic HBV carriers have been published previously [Amini-Bavil-Olyaee et al. 2005].

The phylogenetic analysis of full HBV genome sequences indicated that genotype D, subgenotype D1, is dominant in Iran (98%) confirming previous studies conducted in the area [Amini-Bavil-Olyaee et al. 2005; Doosti et al., 2009]. Subgenotype D2 (2%) represented a small percentage of genotype D infections. The most prevalent subtype was ayw2 two samples carried subtype ayw1 and one adw [Amini-Bavil-Olyaee et al. 2005; Mohebbi et al. 2008; Veazjalali et al. 2009].

The nucleotide divergence of subgenotype D1 strains from Iran, Egypt, and Tunisia was calculated (Table I). Irrespective of distance or continent, subgenotype D1 was remarkably conserved, independently of the geographical origin of the strains. However, in Tunisia, the most distant from Iran, subgenotype D7 was identified that might have evolved from subgenotype D1 [Meldal et al. 2009]. There seemed to be a clear clustering of strains from each country with a few outliers (Fig. 2). The sequences from Iran seemed to form two different clusters and two sequences seemed to cluster with two groups of Egyptian strains. This clustering, however, was not supported by high bootstrap values.

In this cohort of asymptomatic blood donor samples, there were no significant mutations of the MHR of the surface protein apart from one sample presenting sP120Q substitution suggesting a vaccine escape mutant. The same sample also had a 2 aa insertion after position s111. This insertion did not seem to affect the replication of the virus since the viral load was 3.6 × 103 IU/ml and the HBsAg level was 19 IU/ml. There were a few samples with deletions in the pre-S1 and pre-S2 regions which have been reported to lead to intracell accumulation of large surface protein.

The G1896A mutation introduces a stop codon in the PC region that abolishes the production of HBeAg. This mutation was found in 86.2% (75/87) of strains from asymptomatic blood donors in this study but only in 36% of asymptomatic carriers reported by Veazjalali et al. [2009] and in 59.5% (81/136) of HBV patients observed by Mohebbi et al. [2008]. In the study of Amini-Bavil-Olyaee et al. [2005] the G1896A mutation was present in 80% (4/5) of HBeAg negative samples but Poustchi et al. [2008] detected the mutation in 61.5–68.4% of 95 HBeAg negative patients. Unfortunately, the HBeAg status of the carriers studied here is not available and cannot be compared with the previous reports. The premature stop codon was present in 85% of 102 HBV genotype D strains of Tunisian blood donors [Meldal et al., 2009] but only in 4.4% of 23 HBV genotype D strains of Pakistani HBV DNA positive individuals [Ahmed et al., 2009]. Ozgenc et al. [2007] reported the presence of the PC stop codon in 89% of Turkish strains from patients with sustained response at the end of therapy.

The double A1762T/G1764A and G1764T/T1766G mutations were detected in 20.7% and 24.1% of samples, respectively. These results are comparable with those of Mohebbi et al. [2008] who reported 15.4% and 29.4% of chronic patients to have the above double mutations, whereas Poustchi et al. [2008] found that these double mutations were present in 32.7% and 30%, respectively.

Overall, this large-scale study of 50 complete genome HBV sequences of asymptomatic Iranian blood donors confirmed that subgenotype D1, subtype ayw2, is predominant in Tehran, Iran and the PC stop codon is the most common mutation of the virus.

Acknowledgements

We thank the staff of National Blood Transfusion Organization in Tehran, Iran for collecting and testing donor samples.