Preliminary image evaluation performance of radiographers in one New Zealand District: a 6-month prospective study

Abstract

Introduction

Preliminary image evaluation (PIE) is a system where radiographers alert emergency department referrers to the presence or absence of abnormalities on acute extremity X-ray examinations. PIE and similar systems have been utilised in the United Kingdom (UK) and Australia due to a shortage of radiologists to provide a timely report. As New Zealand (NZ) faces a similar shortage, PIE should be considered to address the negative impact this has on patients. The aim of this study was to determine the effect of regular feedback and education on radiographers' performance when detecting and describing acute abnormalities on extremity X-ray examinations in ED.

Methods

A prospective longitudinal study design was utilised for this study. The sensitivity, specificity, accuracy, and accuracy of PIEs performed by seven radiographers at a public provincial district in NZ were assessed over a 6-month period, with the participants provided monthly results along with regular e-mailed feedback on common errors.

Results

The mean for sensitivity, specificity, and accuracy calculated with a 95% confidence interval over the 6-month period were 92.8% (89.9, 95.8), 94.9 (93.1, 96.8), and 94.2 (91.9, 96.5), respectively. When the month-to-month results were analysed, the results demonstrated an improvement in participants' sensitivity, specificity, and accuracy over the 6-month period.

Conclusion

The results of this study demonstrated that radiographers who participated in the study can perform PIE to a high standard that is comparable with the findings from international studies and demonstrated an improvement over 6 months. Therefore, PIE may be useful in NZ to aid ED clinicians in their clinical decisions when a radiology report is unavailable.

Introduction

The potential for radiographers to assist clinical decision making in the emergency department (ED) has evolved significantly over the past 40 years, with abnormality detection systems such as ‘red dot’ reporting, preliminary clinical evaluation in the United Kingdom (UK), and preliminary image evaluation (PIE) in Australia.1-3 PCE and PIE are a feedback system which allows radiographers to write a short comment, alerting referrers to findings, or lack of, on X-ray examinations in ED.4 Importantly, PIE is not a replacement for an official ‘gold standard’ radiology report, but it can assist with clinical decision making for ED clinicians.5 While radiographer reporting is now part of extended practice in the UK in response to a significant shortage of radiologists to provide timely radiology reports, PIE is still used widely, particularly in settings where immediate reporting is not available by reporting radiographers or radiologists.6

Although there is desire for extended practice into radiographer reporting in NZ and Australia,7, 8 and image evaluation is included in undergraduate education,9 radiographer reporting in NZ is not currently supported by the Medical Radiation Technologists Board (MRTB).10 Further, radiologists are an additional barrier to radiographer reporting in Australia and New Zealand, who have outlined they do not support radiographers extending their practice to reporting X-ray examinations.11 This is despite the New Zealand (NZ) public health service having approximately 60 full-time equivalent consultant and registrar radiologists per 1,000,000,12 which frequently results in delays in radiology reports for ED patients. Furthermore, the distribution of radiologists differs by region, where often rural or provincial regions do not have access to a radiologist on-site.11 The average time for a radiology report to be completed in the Taranaki District, a provincial district, between March 2022 and February 2023 was 4.52 days. Additionally, 24.32% of radiology reports were not completed for more than 7 days.13 This delay has led to ED clinicians making treatment decisions without the aid of the radiology report.14 As many of the ED clinicians are junior doctors, nurse practitioners and clinical nurse specialists, concerns have been raised about the performance of these clinicians to interpret X-ray examinations, which can vary with experience.3, 14-16 One study found that ED clinicians sensitivity was as low as 42% with an accuracy of 77%.17 The most common treatment error in ED is missed fractures, accounting for over 77% of treatment errors.18 Additionally, a study conducted in Australia demonstrated that 3.1% of fractures are missed at the time of treatment, only to be discovered when the radiology report became available.19 The same risk may be present within the New Zealand healthcare system as the context is closely aligned to Australia.8

Recent coroner's inquests in Australia have outlined that radiographers who see any abnormalities on an X-ray examination should alert referrers to these findings.20 This was supported by the Medical Radiation Practice Board of Australia, and the MRTB, who both stipulate that all radiographers are responsible for recognising significant findings on X-ray examinations and must communicate these findings to the referrer.16, 21 To allow this communication to occur in a concise and timely manner, a formal system such as PIE has been suggested.5, 14, 16 In the past 10 years, PIE and similar systems have been expanding internationally, with use reported in South Africa, Singapore, Ghana, and significantly in Australia.5, 22-24

There has been extensive research internationally using image evaluation tests demonstrating radiographers' performance in writing PIE comments increases following intensive training.4, 19, 22, 23, 25-30 Although these studies demonstrate that radiographers have an increase in performance immediately following intensive training, studies that follow participants at differing time periods after they have received intensive training have mixed results. For example, two studies demonstrated that participants' performance improved at 10–12 weeks post-training,19, 27 whereas one study showed a return to baseline performance 6 months following training.30

Additionally, several studies discussed radiographer participants' confidence in participating in PIE and found while training increased their participation in PIE, they were still reluctant to write a PIE when they were unsure of the findings.31-34 One suggestion to overcome this barrier was to ensure participating radiographers received regular feedback, which also helped improve the accuracy of the comments.34 However, there is no known research to show the effect of regular feedback on participants' performance to perform PIE clinically. In addition, although there has been research conducted in Australia,3, 35-38 the UK,31, 39, 40 and other countries17, 24 to assess radiographers' performance when writing PIE comments, there is no published research assessing the clinical performance of radiographers in New Zealand.

The aim of this study was to determine what effect fortnightly feedback of common errors, with monthly targeted continuing professional development sessions, had on radiographers' performance when detecting and describing acute abnormalities on extremity X-ray examinations in ED.

Methods

Ethics

Ethics approval was granted by the Auckland Health Research Ethics Committee Application (AH25289) and Te Whatu Ora, Taranaki District Chief Medical Advisor.

Design

A prospective longitudinal study design was used to analyse the sensitivity, specificity, and comment accuracy of PIEs performed by radiographers between 2 April and 30 September 2023 at Taranaki Base, and Hawera Hospitals, within Taranaki District, New Zealand. Each month, the participants' sensitivity, specificity, accuracy, and comment accuracy were analysed to provide regular feedback to the participants on common errors, with the aim of increasing their confidence, and improve their performance during the study.

Sample size calculation

To determine the sample size of X-ray examinations included for evaluation, the number of acute extremity X-ray examinations matching the inclusion criteria in the 12 months preceding the study was determined (7422). An X-ray examination consisted of several X-ray images for the same body part being imaged. As the study period was only 6 months, the number was halved to account for the shorter duration of data collection, yielding an estimated 3711 X-ray examinations that could potentially be encountered during the study period. Following examples in other similar studies performed in Australia,3, 36 an online sample size calculator was used to determine the sample size required to achieve 95% confidence intervals,41 which calculated that 352 X-ray examinations would be required to achieve a representative sample. To ensure there was a full representation of the typical acute extremity examinations performed over the entire 6 months, all PIEs completed during the study period were included in the sample selection, rather than stopping once the sample size was reached. This allowed for any changes in the groups' performance over 6 months to be assessed.

Study setting and participants

The study was conducted at two public hospitals within a single provincial district in NZ. All radiographers who may be rostered to the ED in Taranaki District, either Taranaki Base or Hawera Hospital were invited to participate in the study (N = 28). ED is staffed by one radiographer for each shift, with two shifts each day. Of the eligible radiographers, only nine are rostered exclusively to general X-ray, with the remaining radiographers also rostered to CT and MRI, limiting the time they could work in ED. Seven radiographers (25%) agreed to participate, six of whom work exclusively in general X-ray. It is likely the radiographers who did not agree to participate did so due to the limited time they work in ED.

As the primary researcher also worked in the same department as the participants, the participants' data was kept confidential during the study through the use of a unique identifier each participant created themselves by combining the first three letters of the street name with the house number they lived at on their 21st birthday. For example: 10 Clyde Street would be CLY10. This ensured that results were not traceable back to a particular participant, and ensured the researchers were blinded. Each participant consented to be part of the study and had the right to withdraw at any time, where their data would be removed from the study. PIE was not in use in the Taranaki district prior to the start of this study. Therefore, prior to commencement of the study participants completed a two-day intensive training education programme, for a total of 9 hours. The training programme included specific education on acute extremity X-ray examinations, from shoulder to fingers, and pelvis to toes. Participants were also given instruction on how to write a PIE comment. The course was developed and delivered by an expert in image evaluation, who has qualifications specific to image interpretation (MHSc image interpretation), and who has been teaching image evaluation at a post-graduate certificate level for over 10 years.

Procedure

Immediately following the two-day intensive training programme, the participants were asked to record a written PIE on all included X-ray examinations while working in ED at Taranaki Base and Hawera Hospitals in the radiology information system (RIS), using their unique identifier to enable tracking of the comments to each participant. Included appendicular X-ray examinations were trauma studies that occurred within 14 days of the trauma incident at the time of presentation to ED. Any examination where trauma occurred more than 14 days prior to presentation to ED, pathologies other than trauma such as osteomyelitis or osteoarthritis, or examinations in other body parts were excluded from the study.

Participants were instructed to record their PIEs in the radiology information system (RIS) immediately following the completion of the X-ray examination. The X-ray examinations were viewed on a DICOM monitor in the ED X-ray room. PIEs were extracted from the RIS on a weekly basis along with the official radiology report and imported into an Excel spreadsheet. They were then assessed by a senior radiographer who has extensive experience in PIE. Each PIE comment was assessed against the radiologists' report as being true positive (TP), true negative (TN), false positive (FP) or false negative (FN), with comment accuracy scored using a scoring system adapted from Neep et al.42 This allowed for a simplified system for sensitivity and specificity to be assessed without using partial marks. Additionally, this allowed analysis of the accuracy of the comments made by the participants (Table 1). As well as assessing the accuracy of the contents of the PIE comments, the overall accuracy, determined by calculating the percentage of correct PIEs (TN and TP combined), was also assessed. This demonstrates the accuracy of the PIE system and allows direct comparison with international studies. Any PIEs that were inconsistent with the radiology report were discussed with a senior consultant radiologist.

| Score | Comment score | |

|---|---|---|

| For examinations with a traumatic abnormality | ||

| Abnormality not detected | FN | 0 |

| Abnormality detected but not described correctly, including missed additional abnormalities | TP | 1 |

| Abnormality detected; description incomplete (but not incorrect) | TP | 2 |

| Abnormality detected and correctly described in entirety | TP | 3 |

| For examinations with no traumatic abnormality | ||

| False abnormality reported or described | FP | 0 |

| Correctly identified the absence of traumatic abnormality | TN | 3 |

- FN, False Negative; FP, False Positive; TN, True Negative; TP, True Positive.

Participants were given feedback by the same senior radiographer, in consultation with the senior consultant radiologist, via e-mail every 2 weeks for 3 months starting in May, then every 3 weeks for the remainder of the study. Feedback consisted of guidelines on how to write PIE comments, and examples of common mistakes, for example, missed lipohaemarthrosis or avulsion fractures. General feedback was also passed on each month at in-house continuing professional development meetings. Additionally, each month participants were informed of the group's mean, highest, and lowest sensitivity, specificity, and comment accuracy for the preceding month to provide encouragement by outlining the groups change in performance each month.

Data analysis

Conventional descriptive statistics were performed using SPSS v29.0.0. The mean sensitivity, specificity, and overall accuracy were calculated with 95% confidence intervals. Comment accuracy was not included in the confidence interval calculations because this was only used to form the feedback to the participants.

Results

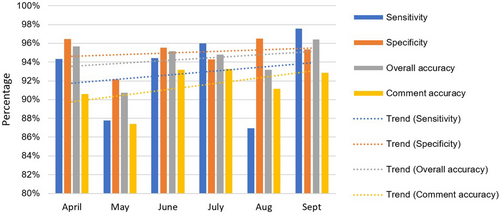

Over the 6-month study period, 844 X-ray examinations were evaluated by the participants, greater than the sample size required. The sample size used aligns with multiple other studies enabling direct comparisons.31, 35, 36, 40 The mean for sensitivity, specificity, and overall accuracy calculated with a 95% confidence interval were 92.8% (89.9, 95.8), 94.9 (93.1, 96.8), and 94.2 (91.9, 96.5), respectively. The mean comment accuracy was 91.41%. When the month-to-month results were analysed (Table 2), a key finding is the lower sensitivity in May and August, which was caused by these months featuring the highest number of false negatives, almost double the average, with a corresponding drop in comment and overall accuracy. Despite these outliers, the trend demonstrated an increase in sensitivity, specificity, overall accuracy, and comment accuracy (Fig. 1).

| Month | TP | TN | FP | FN | Total | Sensitivity (%) | Specificity (%) | Overall accuracy (%) | Comment accuracy (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| April | 50 | 82 | 3 | 3 | 138 | 94.34 | 96.47 | 95.65 | 90.58 |

| May | 43 | 94 | 8 | 6 | 151 | 87.76 | 92.16 | 90.73 | 87.42 |

| June | 51 | 107 | 5 | 3 | 166 | 94.44 | 95.54 | 95.18 | 93.17 |

| July | 48 | 116 | 7 | 2 | 173 | 96.00 | 94.31 | 94.80 | 93.26 |

| August | 40 | 83 | 3 | 6 | 132 | 86.96 | 96.51 | 93.18 | 91.16 |

| September | 40 | 41 | 2 | 1 | 84 | 97.56 | 95.35 | 96.43 | 92.86 |

| Mean | 45.33 | 87.17 | 4.67 | 3.50 | 140.67 | 92.83 | 94.92 | 94.19 | 91.41 |

- FN, False Negative; FP, False Positive; TN, True Negative; TP, True Positive.

The median number of PIEs performed by the participants was 120 (range 24–205), with two significant outliers who performed the fewest number of PIEs, one with a significantly lower sensitivity (Table 3).

| Participant | TP | TN | FP | FN | Total number | Sensitivity | Specificity | Overall accuracy | Comment accuracy |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 36 | 68 | 4 | 1 | 109 | 97.30% | 94.44% | 95.41% | 93.88% |

| 2 | 11 | 13 | 0 | 0 | 24 | 100.00% | 100.00% | 100.00% | 95.83% |

| 3 | 6 | 26 | 0 | 3 | 35 | 66.67% | 100.00% | 91.43% | 86.67% |

| 4 | 44 | 105 | 3 | 4 | 156 | 91.67% | 97.22% | 95.51% | 92.95% |

| 5 | 59 | 135 | 5 | 6 | 205 | 90.77% | 96.43% | 94.63% | 92.52% |

| 6 | 47 | 69 | 8 | 6 | 130 | 88.68% | 89.61% | 89.23% | 86.67% |

| 7 | 69 | 107 | 8 | 1 | 185 | 98.57% | 93.04% | 95.14% | 90.99% |

| Mean | 38.9 | 74.7 | 4 | 3 | 120 | 92.83% | 94.92% | 94.19% | 91.39% |

- FN, False Negative; FP, False Positive; TN, True Negative; TP, True Positive.

Of the 844 examinations, 21 false negatives and 28 false positives were identified. Analysis by anatomical region demonstrates the shoulder, pelvis and knee regions have higher overall accuracy, whereas elbow, wrist and ankle have the lowest overall accuracy (Table 4). The false negatives were assessed (Table 5), and the most common missed abnormalities were in the fingers, hand, and elbow.

| Body region | TP | TN | FP | FN | Total | Sensitivity (%) | Specificity (%) | Overall accuracy (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Shoulder/humerus | 60 | 56 | 2 | 1 | 119 | 98.36 | 96.55 | 97.48 |

| Elbow/forearm | 33 | 43 | 3 | 4 | 83 | 89.19 | 93.48 | 91.57 |

| Wrist/hand | 97 | 147 | 6 | 11 | 261 | 89.81 | 96.08 | 93.49 |

| Pelvis/femur | 29 | 67 | 3 | 0 | 99 | 100.00 | 95.71 | 96.97 |

| Knee/tibia | 19 | 96 | 3 | 1 | 119 | 95.00 | 96.97 | 96.64 |

| Ankle/ft | 34 | 114 | 11 | 4 | 163 | 89.47 | 91.20 | 90.80 |

| Total | 272 | 523 | 28 | 21 | 844 | |||

| Mean | 45.3 | 87.2 | 4.7 | 3.5 | 140.7 | 92.83 | 94.92 | 94.19 |

- FN, False Negative; FP, False Positive; TN, True Negative; TP, True Positive.

| Body part | Number of FN | Findings (number of examinations) |

|---|---|---|

| Finger | 6 | Subtle tuft fracture (3) Avulsion fracture of distal phalanx (2) Missed foreign body (1) |

| Elbow | 4 | Joint effusion representing occult fracture (3) Joint effusion with medial epicondyle fracture (1) |

| Hand | 3 | Un-displaced distal phalanx fracture (2) Neck of 5th metacarpal fracture (1) |

| Ankle | 2 | Avulsion fracture to talus (1) Avulsion fracture to distal fibula (1) |

| Wrist | 2 | Buckle fracture (1) Comminuted radial fracture (1) |

| Foot | 2 | Fracture of distal phalanx of the great toe (1) Avulsion fracture to talus (1) |

| Knee | 1 | Missed lipohaemarthrosis (1) |

| Shoulder | 1 | Surgical neck fracture – also missed by radiologist at time of report, detected on concurrent CT scan. |

- CT, computed tomography; FN, false negatives.

There were only two studies that were marked as TP that had additional missed fractures. Both examinations involved complicated fractures, such as a bimalleolar fracture where only a Weber B fracture was noted, and a missed hook of hamate fracture in context of carpometacarpal dislocation.

During the assessment of PIEs, 10 of the 273 (3.7%) X-ray examinations with acute abnormalities had findings identified by participants who were not identified in the radiologist report. A senior radiologist assessed these studies, and in all instances the abnormalities were deemed to be missed by the reporting radiologist. The affected radiology reports were amended, and the referrers were notified ensuring the patient received the appropriate follow-up that was required. Six of these studies were missed abnormalities in the fingers or thumb, one was in an elbow, two were in the hip, and one was in a knee, similar to the findings of the missed abnormalities by the radiographers.

Discussion

This is the first known study about preliminary image evaluation to be conducted in New Zealand. The participants in this study demonstrated a sensitivity, specificity, and overall accuracy at a similar level of, or greater when compared to similar PIE studies conducted internationally (Table 6).3, 24, 31, 35, 36, 38, 40 Additionally, the participants demonstrated an increase in their performance over the 6 months of the study period.

| Study | Sensitivity (%) | Specificity (%) | Overall accuracy (%) | Abnormality prevalence (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Brown et al.3 | 71.1 | 98.4 | 92.0 | – |

| Del Gante et al.24 | 94.3 | 98.2 | 96.9 | 35.0 |

| Lidgett et al.31 | 86.0 | 91.0 | 90.0 | 35.5 |

| McConnell et al.38 | 94.2 | 95.3 | 95.0 | 31.6 |

| Petts et al.36 | 80.0 | 98.0 | 92.0 | 19.6 |

| Smith & Younger35 | ||||

| Upper extremity | 99.1 | 93.9 | 96.3 | 45.2 |

| Lower extremity | 98.2 | 93.0 | 95.0 | |

| Verrier et al.40 | 84.0 | 97.0 | 92.0 | 35.5 |

| This study | 92.8 | 94.9 | 94.2 | 34.7 |

The aim of this study was to determine what effect fortnightly feedback of common errors, with monthly targeted continuing professional development sessions, had on radiographers' performance when detecting and describing acute abnormalities on extremity X-ray examinations in ED. To achieve this aim, the comment accuracy was used to form the feedback given to participants with the intention of improving their performance when detecting and describing acute abnormalities, and therefore increase their confidence to participate.32 When the analysis was first conducted on the results from April, a key finding was that despite a high overall accuracy, the comment accuracy was low in comparison. One study conducted in the UK outlined that many PIE comments contained too many words which reduced their comment accuracy.43 The lower comment accuracy in this study implied a similar phenomenon was occurring. It was decided that the participants required further guidance on how to write PIE comments. Feedback was therefore given to the participants to follow the “3Ws of PIE” outlined by Cooper et al.,14 “What is it, where is it, what is it doing.” While comment accuracy continued to be lower than overall accuracy, the margin was much closer for the remainder of the study. Although it was encouraging that participants' performance when performing PIE improved over 6 months, as PIE was not implemented into the department prior to the start of the study this increase in performance may be due to experiential learning, rather than the ongoing feedback. Further research would be required in a department with PIE previously established to determine whether follow-ups make a difference to participants' performance when detecting and describing acute abnormalities on extremity X-ray examinations. As confidence in writing PIE comments is a major barrier to radiographers participating in a PIE system,44 it is suggested that the ongoing feedback could be useful to help remove this barrier for departments planning on implementing PIE in the future.

A further finding in this study is the number of missed abnormalities, by both the participants and the radiologists. These were prominently in the fingers, toes, wrist, and ankle, with avulsion fractures making up the majority of missed fractures. This is a common finding in other studies.40, 45 This finding demonstrates the importance of educating radiographers on the appearance of avulsion fractures, and that vigilance is required when searching for acute abnormalities, as small avulsion fractures are easily missed. Of note, 3.7% of abnormalities during this study were detected by the radiographer but missed by the reporting radiologist. Although the majority of the abnormalities were avulsion fractures, this study demonstrated that working together, a PIE with radiology report can help improve the accuracy of acute abnormality detection.

The number of X-ray examinations with missed additional acute abnormalities was minimal in this study, with only two in the context of significant trauma. It is likely these missed abnormalities were due to satisfaction of search, where participants stop searching for abnormalities in cases where obvious abnormality is present.14 Therefore, it is vital to ensure that when participating in PIE, participants receive education around satisfaction of search.

The abnormality prevalence in this study (34.7%) is higher than the anticipated prevalence based on an internal audit of the preceding year (26%). However, the prevalence found in this study is aligned with, or lower than the prevalence found in other similar studies.17, 24, 31, 35, 40 The most likely cause of the higher prevalence is a result of participants not writing PIE comments on studies that did not have an abnormality. This has the potential to skew the sensitivity higher, and the specificity lower.46 However, it is also established that the higher prevalence could represent case selection bias, and suggests that participants may only be writing PIE comments on X-ray examinations they feel confident in.47 The findings suggest that feedback and continuing professional development sessions can help maintain, or improve PIE performance, and therefore a robust audit and feedback system should be considered as part of a PIE system.

Limitations

The key limitations to this study are the main biases that exist: case selection bias and participant bias.46 Case selection bias is where participants would only complete PIEs on X-ray examinations they felt confident in.47 Regular communication and training was provided to help build radiographer confidence and minimise this bias. The second bias was participant bias, where only those participants who are interested in PIE volunteered to be a part of the study, and therefore the results are not an indication of the entire population at the study site. As this is a clinical study, this bias was minimised by assessing participants in their daily practice over a period of 6 months, ensuring their performance was assessed on an ongoing basis. Although these were identified as limitations, the biases were minimised as much as possible by ensuring there was an appropriate sample size collected over the entire study period to help minimise the potential for these to impact the results.

Another limitation in this study is the small population size. While the sample size ensured that the results were an accurate demonstration of the PIE performance of radiographers working in the Taranaki district, it cannot be certain that these results would extend to the wider radiographer population in NZ. It is recommended that further study is done to determine the performance of radiographers in NZ as a whole.

Conclusion

This study demonstrates that participants performed PIE to a high standard, which is comparable with radiographers internationally. Additionally, participants improved their performance when detecting and describing acute abnormalities over the course of the study. However, the study was unable to determine if this improvement was due to the ongoing feedback, or experiential learning. This study demonstrates radiographers working in two public hospitals within a single provincial district in NZ have a high level of sensitivity, specificity, and accuracy when performing PIE in ED. This suggests PIE would be useful to assist NZ ED clinicians with their treatment decisions when a radiology report unavailable. In addition, the number of missed acute appendicular abnormalities in ED will likely be reduced. It is recommended that participants in a PIE system receive training and ongoing feedback to provide confidence and support to ensure they can maintain their performance when detecting and describing abnormalities on acute extremity X-ray examinations.

Acknowledgements

The authors wish to acknowledge Helen Vere for her work in assessing the PIEs and creating the feedback e-mails and CPD sessions. Also to Heather Gunn for facilitating the training sessions. Acknowledgements to the New Zealand Institute of Medical Radiation Technology Continuing Education Fund for travel and accommodation funds for the intensive training course facilitator.

Funding Information

Funds were provided by the New Zealand Institute of Medical Radiation Technology Continuing Education Fund for travel and accommodation funds for the intensive training course facilitator.

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Ethics Approval

Ethics approval was granted by the University of Auckland Ethics committee (AH25289) and Te Whatu Ora, Taranaki District Chief Medical Advisor.

Open Research

Data Availability Statement

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request. The data are not publicly available due to privacy or ethical restrictions.