The Genetic Information Nondiscrimination Act and workplace genetic testing: Knowledge and perceptions of employed adults in the United States

The INSIGHT @ Work Consortium team members are listed in Acknowledgments section.

Abstract

Workplace wellness programs are an emerging avenue for health-related genetic testing, with some large employers now offering such testing to employees. Employees' knowledge and concerns regarding genetic discrimination may impact their decision-making about and uptake of workplace genetic testing (wGT). This study describes employed adults' objective knowledge of the Genetic Information Nondiscrimination Act (GINA) and evaluates how this knowledge correlates with attitudes and beliefs regarding wGT. Analyses utilized data from a large, national web-based survey of employed adults (N = 2000; mean age = 43 years; 51% female; 55.2% college educated). Overall, most respondents (57.3%) said they were unaware of any laws protecting against genetic discrimination. Specifically, 62.6% indicated they were not at all familiar with GINA. The primary study outcome was respondents' score on a 13-item measure assessing knowledge of basic facts about GINA. Participants had low overall GINA knowledge (M = 4.6/13 items correct (35%), SD = 2.9), with employees often presuming GINA offers greater legal protections than it does (e.g., 45.3% erroneously endorsed that GINA protected against discrimination in life insurance). Logistic regression analyses assessed associations between GINA knowledge and employees' demographic characteristics, prior experience with genetic testing, and attitudes regarding wGT. Variables significantly associated with GINA knowledge included higher interest in wGT (aOR = 1.45; 95% CI: 1.20, 1.77), self-reported familiarity with GINA (aOR = 2.02; 95% CI: 1.64, 2.50), and favorable attitudes toward wGT (aOR = 1.92; 95% CI: 1.52, 2.44). Results indicate public knowledge of GINA remains low over 15 years after its passage. These findings highlight the need for employee education on GINA before participating in wGT, as well as broader public education on GINA's legal protections and limitations. Genetic counselors lead GINA education efforts in clinical and public settings and can play a pivotal role in ongoing public education initiatives about GINA.

What is known about this topic

Workplace wellness programs are an emerging avenue for health-related genetic testing, wherein some large employers are now offering such tests as a benefit to their employees. However, little is known about employees' objective knowledge of legal protections against genetic discrimination in this and other genetic testing contexts, and what factors are associated with higher versus lower knowledge.

What this paper adds to the topic

This paper presents new data on employed adults' objective knowledge of the Genetic Information Nondiscrimination Act (GINA), further evaluating how this knowledge correlates with their attitudes and beliefs related to workplace genetic testing. Based on a large national survey of a diverse sample of employed adults, this paper identifies factors associated with GINA knowledge, ultimately highlighting gaps in education on this important anti-discrimination legislation.

1 INTRODUCTION

Scientific advancements have led to considerable growth in genetic testing outside of traditional clinical settings. Direct-to-consumer (DTC) genetic testing became available in the early 2000s (Allyse et al., 2018) and has now surpassed ten million genotyped consumers (Khan & Mittelman, 2018). More recently, some companies market whole genome sequencing to ostensibly healthy adults (Samlali et al., 2022). Employer-sponsored wellness programs have emerged as another non-clinical setting in which genetic testing has been initiated. Workplace genetic testing (wGT) programs are typically implemented by employers via third-party vendors, with a review by McDonald et al. (2020) identifying 15 vendors of wGT services. Some major corporations across different employment sectors (e.g., Apple, General Electric, Levi Strauss & Company, Visa) are reported to offer wGT programs to their employees (Singer, 2018).

To date, few studies have explored employee perspectives and beliefs about wGT. A recent study at a large biomedical institution found that its employees reported they would be most comfortable with genomic testing if offered in a workplace setting, compared to a doctor's office or via DTC testing services (Sanghavi et al., 2021). However, these employees also indicated a strong interest in knowing more about the confidentiality of test results, privacy protections, and the existence of relevant laws and policies before agreeing to genetic testing (Sanghavi et al., 2021). These results demonstrate a need to explore the extent to which employees in the United States who may be offered wGT are aware of and knowledgeable about relevant policies regarding genetic discrimination.

A key legal protection in this area is the Genetic Information Nondiscrimination Act (GINA), a federal law passed in 2008. The definition of genetic information under GINA includes both results of genetic tests and family medical history (Prince & Roche, 2014). GINA bars employers and health insurers from accessing or requesting an individual's genetic information and protects against genetic discrimination in these settings; however, there are a few notable limitations. For example, while GINA protects one's genetic information, it does not offer protections for manifested genetic conditions (e.g., having signs or symptoms of the condition). Also, GINA does not cover employers with fewer than 15 employees, nor does it apply to life, disability, or long-term care insurers (Prince & Roche, 2014). Additional collection exceptions include voluntary workplace wellness programs and insurance companies' requests for genetic test results from patients to assess claims for preauthorization or coverage of services indicated by certain genetic test findings (e.g., colonoscopy for patients whose genetic test results indicate Lynch syndrome). Previous studies suggest public awareness and knowledge of GINA is low. Wauters and Van Hoyweghen (2016) conducted a systematic review of 42 publications addressing fears and concerns of genetic discrimination, where they found a general lack of public awareness among participants regarding protections against genetic discrimination. A more recent survey evaluating public knowledge of GINA (Lenartz et al., 2021) highlighted the continued lack of awareness of the law over a decade after its passage, with nearly half (46.3%) of the respondents reporting low subjective knowledge of GINA.

GINA awareness is not widespread, but the legal protections against genetic discrimination and their limitations may be important considerations for individuals offered wGT. One study demonstrated that while only 20% of the adult population sampled reported awareness of GINA, the importance of laws that protect against genetic discrimination was perceived as high, with more than 80% of respondents rating these types of laws as somewhat or very important (Parkman et al., 2015). The aforementioned Lenartz et al. (2021) survey also revealed that many respondents indicated they would decline genetic testing based on concerns about genetic discrimination in the employment setting.

These findings highlight the importance of evaluating knowledge of legal protections against genetic discrimination among employed adults in the United States to understand how such knowledge may play a role in employee decisions about wGT. Much of the existing literature on GINA knowledge is limited to a focus on specific clinical populations (e.g., patients undergoing cancer genetic testing), and no studies, to our knowledge, have examined links between GINA knowledge and attitudes toward genetic testing in the workplace. In this study, we ascertained employed adults' objective knowledge of existing legal protections against genetic discrimination and analyzed results to help determine how such knowledge is associated with employee interest in and attitudes about wGT.

2 MATERIALS AND METHODS

2.1 Participants and procedures

A web-based survey was administered to a diverse, national sample of 2000 participants recruited via Dynata, a third-party survey firm. Dynata uses several quality control measures to validate survey takers and ensure responses are legitimate, including identity confirmation such as two-factor authentication and utilization of a third-party database to match the individual's existence in the real world (e.g., via characteristics such as income range, home ownership, or location information). Dynata also utilizes automated technologies to spot anomalies and outliers in survey-taking behavior.

Participants were eligible if they were (a) 18 years or older and (b) employed full or part-time by a third-party employer. Individuals were compensated for their participation by Dynata at their existing rates. Data collection took place from February through March 2022. Participants accessed a study information sheet and indicated their informed consent to access the web-based survey. The University of Michigan Institutional Review Board (IRB) approved this study after their review determined it to be exempt from ongoing IRB oversight (HUM00210267).

2.2 Instrumentation

The survey items utilized in this study were selected from a broader survey instrument developed as part of an ongoing, NIH-funded study on the ethical, legal, and social implications of wGT. Measures of employees' awareness and knowledge of GINA, including their concerns, interest, and attitudes about wGT, were the focus of this sub-analysis, with these survey domains described in greater detail below. A complete list of survey items used for this paper can be found in Appendix S1.

2.2.1 Demographics

Standard self-report items ascertained respondents' demographic characteristics, including age, sex, race and ethnicity, level of education, employer sector, and household income.

2.2.2 Awareness of GINA

Three items assessed participants' overall awareness of existing laws protecting against genetic discrimination and, specifically, participants' perceived knowledge of GINA. These items were based on the survey by Lenartz et al. (2021).

2.2.3 Objective knowledge of GINA

In total, 13 survey items assessed participants' objective knowledge of GINA. These items addressed different aspects of GINA, including (a) protections provided by GINA, (b) entities covered under GINA, and (c) specific examples of genetic discrimination in the employment and health insurance contexts. An overall GINA knowledge score was created by summing correct responses across the 13 items (range: 0–13). An interdisciplinary team with expertise in clinical, legal, and ethical issues of genetic testing developed the knowledge measure using both novel survey items and modified versions of three existing validated measures. Survey measures included five verbatim items from Lenartz et al. (2021), one modified survey item from Linderman et al. (2021), and one modified survey item from Morren et al. (2007). Six survey items were novel items developed by the interdisciplinary team after an extensive literature review of multiple sources covering similar concepts.

2.2.4 Attitudes and interest regarding wGT

Survey items addressed employee attitudes and interest regarding wGT. Attitudes about wGT were measured using four items asking respondents about perceptions of wGT utility and limitations. Responses on these items were summed (with two items reverse scored) to yield an overall attitude score ranging from 4 to 20, with higher scores indicating more favorable attitudes toward wGT. Assessment of interest in wGT included a two-part question asking if respondents had ever participated in a wGT program and (if not) whether they would be interested in participating. Those who answered “yes” to either of these items were categorized as having interest in wGT, with all others classified as not having test interest.

2.3 Data analysis

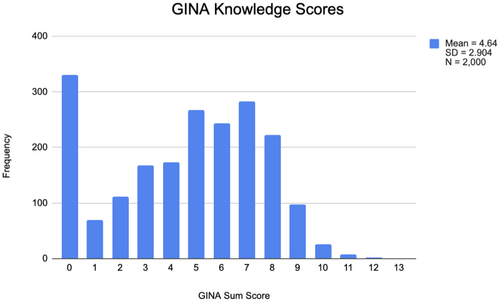

Descriptive statistics, including means and frequencies, were used to characterize the sample in terms of (a) demographic and employment characteristics and (b) item-level responses for outcomes of interest, including knowledge of GINA and attitudes toward wGT. A logistic regression analysis assessed whether key demographic variables (e.g., age, sex, race and ethnicity, level of education) and participants' wGT attitudes and beliefs were associated with lower versus higher GINA knowledge. The dependent variable was respondents' overall score on the GINA knowledge measure. Given that the overall GINA knowledge scores were not normally distributed (i.e., negatively skewed with a high proportion of respondents scoring zero), we used a median split to dichotomize respondents in lower (0–5 points) versus higher (6–13 points) knowledge categories. Data analyses were conducted using statistical software packages SPSS version 28.0 and R version 4.2.3.

3 RESULTS

3.1 Respondent characteristics

Participants (N = 2000) were, on average 43 years old, 51.1% female, and well-educated, with 55.2% having a college degree or higher (Table 1). The sample was diverse, with 13.6% identifying as Black (non-Hispanic), 8.2% as Asian, and 8.4% as Hispanic or Latino. The participants encompassed various professions and sectors of employment, reflecting a diversity of the categories reported by the U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics from the “Occupational Employment and Wage Statistics” (U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics, 2023). Among these, the predominant categories within our sample were “Education, training, and library” (11.1%), “Sales” (9.6%), and “Management” (9.3%).

| Characteristic | N (%) | M (SD) [range] |

|---|---|---|

| Age: (years) | 43.14 (14.17) [18–82] | |

| Sex | ||

| Female | 1022 (51.1) | |

| Male | 978 (48.9) | |

| Race and ethnicity | ||

| White, non-Hispanic | 1344 (67.2) | |

| Black, non-Hispanic | 272 (13.6) | |

| Asian | 163 (8.2) | |

| Hispanic or Latino | 167 (8.4) | |

| American Native or Native Alaskan | 16 (0.8) | |

| Native Hawaiian or other Pacific Islander | 6 (0.3) | |

| Multi-race | 23 (1.2) | |

| None of these describe me | 9 (0.5) | |

| Education | ||

| High school or less | 292 (14.6) | |

| Some college | 606 (30.3) | |

| College graduate | 663 (33.2) | |

| Professional/doctoral degree | 439 (22.0) | |

| Employer sector | ||

| Healthcare/pharmaceutical industry | 272 (13.6) | |

| Technology/biotechnology | 203 (10.2) | |

| Other | 1525 (76.3) | |

| Household income | ||

| $100,000 or more | 683 (34.2) | |

| $50,000–$99,999 | 838 (42.0) | |

| <$50,000 | 479 (24.0) | |

- Abbreviations: M, median; N, sample size; SD, standard deviation.

3.2 Awareness and perceived knowledge of GINA

In this study, 57.3% of respondents reported being unaware of any laws protecting against genetic discrimination, and 20.4% reported being unsure. Only 22.4% of all participants reported that they were aware of laws that protect against genetic discrimination. When all respondents were asked more specifically about familiarity with GINA, 62.6% of respondents reported they were not at all familiar, 24% reported being somewhat familiar, and 13.4% reported being extremely familiar.

3.3 Objective knowledge of GINA

Respondents' mean score on the GINA Knowledge Scale was 4.6 out of 13 items (SD = 2.9; median = 5.0; range 0–12) (Figure 1). No participants answered all questions correctly, and only 44.1% correctly answered six or more items. Across all questions, 32% or more indicated “I don't know,” and, notably, this was 40% or higher for six of the 13 questions.

Most participants failed to correctly respond to questions about what entities were covered (or not) under GINA (Table 2). Almost half of the respondents correctly responded that GINA applies to people who have undergone genetic testing and people with a family history of a genetic condition. However, only 19.4% of participants correctly identified that GINA protections do not apply to manifested conditions, and just 17.8% of participants correctly identified that GINA does not apply to all U.S. employers (Table 2). About half of respondents correctly answered that GINA protects against genetic discrimination in employment and health insurance. However, only a minority of respondents correctly identified GINA's limitations regarding life (13.3%), disability (13.8%), and long-term care (14.5%) insurance.

| Question | Yes | No | I do not know |

|---|---|---|---|

| N (%) | N (%) | N (%) | |

| Does the Genetic Information Non-Discrimination Act (GINA) apply to the following groups? | |||

| People who have undergone genetic testing | 969 (48.4) | 237 (11.9) | 794 (39.7) |

| People who have symptoms of a medical condition | 749 (37.5) | 387 (19.4) | 864 (43.2) |

| People with a family history of a medical condition | 980 (49.0) | 255 (12.8) | 765 (38.3) |

| All employers in the U.S. | 750 (37.5) | 357 (17.8) | 893 (44.7) |

| Does GINA protect against genetic discrimination in the following areas? | |||

| Employment | 1066 (53.3) | 200 (10.0) | 734 (36.7) |

| Health insurance | 1047 (52.4) | 212 (10.6) | 741 (37.1) |

| Life insurance | 905 (45.3) | 266 (13.3) | 829 (41.4) |

| Disability insurance | 912 (45.6) | 276 (13.8) | 812 (40.6) |

| Long-term care insurance | 812 (40.6) | 289 (14.5) | 899 (45.0) |

| Are the following allowed under GINA? | |||

| A health insurer increases premium rates for someone who tests positive for a genetic condition | 431 (21.6) | 901 (45.1) | 668 (33.4) |

| A health insurer denies coverage for someone with a family history of a genetic condition | 396 (19.8) | 949 (47.4) | 655 (32.8) |

| An employer does not hire someone because they have a family history of a genetic condition | 302 (15.1) | 1060 (53.0) | 638 (31.9) |

| Employers can collect genetic information from employees as part of workplace wellness programs | 729 (36.4) | 460 (23.0) | 811 (40.6) |

- Note: Correct responses are highlighted in bold.

- Abbreviations: GINA, Genetic Information Non-Discrimination Act; N, sample size; U.S., United States.

Lastly, when given several genetic discrimination scenarios in the contexts of employment and health insurance, only 36.4% of participants correctly identified that employers can legally collect genetic information from employees as part of workplace wellness programs under GINA. Almost half of the respondents (48.4% and 49.0%, respectively) knew that under GINA, a health insurer cannot legally increase premium rates for someone who tests positive for a genetic condition or deny coverage for someone with a family history of a genetic condition. More than half (53%) of respondents knew that an employer cannot refuse to hire someone because they have a family history of a genetic condition.

3.4 Factors associated with higher versus lower GINA knowledge

A binomial logistic regression (Table 3) tested for significant relationships between variables of interest and higher or lower GINA knowledge. Demographic characteristics including sex, age, education, household income, and employment sector were not significantly associated with GINA knowledge. However, variables including interest in wGT, familiarity with GINA, and attitudes regarding wGT were significantly associated with GINA knowledge. Participants who endorsed interest in wGT were more likely to have higher GINA knowledge (aOR = 1.45; 95% CI: 1.20, 1.77). Additionally, participants with more favorable attitudes regarding wGT were more likely to have higher GINA knowledge (aOR = 1.92; 95% CI: 1.52, 2.44). Finally, participants who reported being familiar with GINA were more likely to have higher GINA knowledge (aOR = 2.02; 95% CI: 1.64, 2.50).

| Participant characteristic | GINA knowledge OR (95% CI) |

|---|---|

| Sex | |

| Female | 0.96 (0.79, 1.16) |

| Male | 1.00 |

| Age | |

| 18–34 | 0.92 (0.70, 1.20) |

| 35–54 | 1.16 (0.91, 1.47) |

| 55 and above | 1.00 |

| Race and ethnicity | |

| Black, non-Hispanic | 1.31 (0.99, 1.73) |

| Asian | 1.23 (0.87, 1.74) |

| Hispanic or Latino | 1.19 (0.87, 1.72) |

| American Indian or Alaskan Native | 0.25 (0.04, 0.94) |

| Native Hawaiian or other Pacific Islander | 0.50 (0.07, 2.75) |

| Multi-Race | 0.60 (0.22, 1.48) |

| None of these describe me | 0.65 (0.13, 2.51) |

| White, non-Hispanic | 1.00 |

| Education | |

| Professional degree | 1.00 (0.71, 1.41) |

| College graduate | 1.17 (0.86, 1.60) |

| Some college | 0.99 (0.73, 1.33) |

| High school or less | 1.00 |

| Household income | |

| $100,000 or more | 1.00 (0.75, 1.32) |

| $50,000–$99,999 | 0.98 (0.77, 1.26) |

| <$50,000 | 1.00 |

| Interest in wGT | |

| Yes | 1.45 (1.20, 1.77)* |

| No | 1.00 |

| Previous genetic testing experience | |

| Yes | 1.00 (0.81, 1.24) |

| No | 1.00 |

| Attitudes about genetic discrimination | |

| Unfavorable | 1.24 (0.97, 1.58) |

| Favorable | 1.92 (1.52, 2.44)* |

| Neutral | 1.00 |

| Personal history of common diseases | |

| At least one disease | 1.11 (0.94, 1.46) |

| None | 1.00 |

| Family history of common diseases | |

| At least one disease | 1.17 (0.94, 1.46) |

| None | 1.00 |

| Familiarity with GINA | |

| Familiar | 2.02 (1.64, 2.50)* |

| Not familiar | 1.00 |

- Note: Bolded values are significantly associated with GINA knowledge.

- Abbreviations: CI, confidence interval; GINA, Genetic Information Non-Discrimination Act; OR, odds ratio; wGT, workplace genetic testing.

- * p < 0.001.

4 DISCUSSION

To the best of our knowledge, this is the first national study to ascertain public knowledge of GINA in the context of wGT. This novel study has extended previous work on GINA knowledge and awareness by evaluating employed adults' existing knowledge of GINA and its relationship to attitudes and interest in wGT. Most related studies evaluating genetic discrimination knowledge have focused on specific patient or provider populations. In comparison, this study utilized a large, diverse national sample of employed adults in the United States. Our assessment of objective knowledge of legal protections against genetic discrimination is one of the most comprehensive assessments of public knowledge of GINA to date in terms of the number of questions asked and topics explored.

A primary finding of this survey is that public knowledge of GINA is low, with most participants reporting they were not at all familiar with GINA and unable to demonstrate knowledge of basic facts regarding the law's protections and limitations. This was evident by the high percentage of “do not know” and incorrect responses. Importantly, the items most often answered incorrectly were those regarding GINA's limitations for coverage of life, disability, and long-term care insurance. These results are consistent with existing literature that has demonstrated GINA knowledge to be low among the general public, including the survey by Lenartz et al. (2021) that concluded there is a persistent lack of knowledge and misunderstanding of GINA. The existing literature on this topic has generally focused on specific patient populations; however, this survey's large, diverse national sample suggests this lack of knowledge is common across employed adults in the United States. An appropriate understanding of the protections and limitations of GINA related to wGT is necessary for employed adults to understand the potential implications of their test results and make an informed decision about undergoing testing.

4.1 Implications for practice and policy

Genetic testing offered to employees via their employer raises ethical, legal, and policy concerns about the confidentiality and use of private health information. For employees to make an informed decision regarding wGT, they need to understand existing legal protections against genetic discrimination. Our findings highlight that many participants appeared to know nothing at all about GINA, including the legal protections it offers or its limitations. The low levels of GINA knowledge observed in this survey, even among those with prior genetic testing experience, raise concerns about whether employees undergoing wGT are providing truly informed consent to this service. Results of this analysis demonstrated that self-reported familiarity with GINA, as well as interest in and more favorable attitudes about wGT, were associated with higher GINA knowledge. Demographic characteristics, including age, sex, and education, were not significantly associated with higher GINA knowledge, consistent with recent related literature (Lenartz et al., 2021). These findings suggest that uptake of wGT programs may depend more on employee attitudes and experiences rather than demographic characteristics. Participants who were interested in wGT and who reported favorable attitudes regarding wGT were more likely to have higher GINA knowledge; therefore, providing education on GINA in the context of wGT programs may be beneficial for employers who decide to implement these programs. Specifically, educating employees about the limitations and gaps of GINA may inform decisions about undergoing wGT, as our survey results suggest that employed adults in the United States are biased to assume GINA offers more extensive legal protections against genetic discrimination than it actually does.

Genetic counselors are often at the front line of addressing genetic testing with patients and play a key role in pre- and post-test counseling. Pre-test genetic counseling in asymptomatic patients often involves explaining insurance implications of test results and mention of GINA's protections and limitations. For individuals undergoing genetic testing in DTC and wGT settings, formal pre-test genetic counseling is generally omitted. Therefore, unless GINA is addressed in testing materials, readily available on the laboratory website, or researched by the individual undergoing testing, this information may be unknown. Genetic counselors should bear this potential lack of GINA knowledge in mind if patients contact them to discuss wGT either prior to undergoing testing or after receiving results.

The National Society of Genetic Counselors (NSGC) has issued a statement about wGT, expressing that genetic information collected through wGT should be defined in accordance with GINA, and participants who choose to share their genetic information through these programs “should undergo a separate informed consent process and have access to healthcare professionals with genetics expertise, such as certified genetic counselors” (National Society of Genetic Counselors, 2017). Other organizations have also made statements regarding wGT and GINA, prompted in part by the 2017 introduction of the H.R. 1313 bill (Preserving Employee Wellness Programs Act, 2017) in the House of Representatives. This bill would have allowed employers to impose financial penalties on employees who choose not to participate in genetic testing as part of workplace wellness programs, effectively limiting GINA's existing protections in the workplace setting. The American Society of Human Genetics issued a statement directly opposing the bill (American Society of Human Genetics, 2017), and the American College of Medical Genetics & Genomics later published a similar statement emphasizing the importance of maintaining comprehensive protections against genetic discrimination, including in the wGT setting (Seaver et al., 2022). Despite strong support from these professional organizations for protective measures against genetic discrimination, an ongoing challenge lies in raising public awareness about GINA. Additionally, maintaining and expanding current educational resources to ensure accurate interpretation of GINA is crucial, given the complexity of the law and the need for up-to-date information to reach employees and genetic counselors alike.

Given results of this and prior related studies, it is important to continue and expand public education efforts on GINA. These efforts would best be addressed through a multifaceted approach, including vendors offering DTC and wGT programs, the larger genetics community, and policymakers. DTC and wGT programs should ensure insurance discrimination is addressed as a risk and provide resources addressing GINA. Genetics professional organizations can also work to ensure GINA information is readily accessible on their websites. Notably, the NSGC has created an online GINA fact sheet (National Society of Genetic Counselors, 2021). However, ensuring the distribution of this resource to individuals seeking insights for informed decisions on genetic testing remains an ongoing challenge. It remains crucial for genetic counselors and other healthcare providers to stay up-to-date on how the changing landscape of genetic testing in non-clinical settings intersects with GINA's protections and limitations. Employer outreach is also an important part of increasing public knowledge of GINA. Employers offering wGT should be aware of their obligations under GINA and the importance of protecting employees' genetic information. Employers can disseminate information about GINA to their employees through handbooks, training sessions, and internal communications.

4.2 Study limitations/future directions for research

Our study had notable limitations that should be kept in mind when interpreting findings. Although survey respondents were a large, diverse sample of employed adults, individuals who completed the survey through Dynata were members of an existing survey panel, meaning that results from this survey may not be generalizable to all employed adults in the United States. Some survey measures, including the primary study outcome measure of GINA knowledge, included novel questions created specifically for this study; it may be useful for future studies to formally validate these measures. In addition, a mixed methods approach combining quantitative surveys and qualitative interviews could help illuminate employees' understanding of GINA and provide insights into how they weigh the pros and cons of genetic testing in a workplace context.

5 CONCLUSION

This study contributes to the relatively limited literature on wGT and highlights the ongoing lack of public knowledge and awareness of GINA, especially regarding GINA's gaps and limitations in coverage. This study suggests that, in the context of wGT, there is a need for greater employee education on GINA, as well as the law's limitations, as this knowledge is essential for informed consent before undergoing genetic testing and may inform employees' decisions on wGT as a whole.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

Lindsay Willard made substantial contributions to the data interpretation and drafting of the manuscript. Wendy Uhlmann made substantial contributions to the project development and design, data collection, data analysis, data interpretation, drafting of the manuscript, and critical revision of the manuscript. Anya E. R. Prince made contributions to the project development and design, data collection, data analysis, data interpretation, and critical revision of the manuscript. Drew Blasco made contributions to the project design, data analysis and interpretation, and critical revision of the manuscript. Subhamoy Pal made significant contributions to the data analysis and interpretation. J. Scott Roberts made contributions to the project development and design, data collection, data analysis, data interpretation, and critical revision of the manuscript. Authors Lindsay Willard and J. Scott Roberts confirm that they had full access to all the data in the study and take responsibility for the integrity of the data and the accuracy of the data analysis. All the authors gave final approval of this version to be published and agreed to be accountable for all aspects of the work in ensuring that questions related to the accuracy or integrity of any part of the work are appropriately investigated and resolved.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The INSIGHT @ Work Consortium consists of the following core team members, in addition to the named authors: Rachael Brandt, PhD, MS (Jefferson Health), Elizabeth Charnysh, M.S., C.G.C. (The Jackson Laboratory for Genomic Medicine), Betty Cohn, M.B.E. (University of Washington), Nicole Crumpler, M.S., M.B.A. (Jefferson Health), W. Gregory Feero, M.D., Ph.D. (Maine-Dartmouth Family Medicine Residency), Rebecca Ferber, M.P.H. (University of Michigan), Veda Giri, M.D. (Yale School of Medicine), Katherine Hendy, Ph.D., M.A. (University of Michigan), Debra Mathews, Ph.D., M.A. (Johns Hopkins University), Sarah McCain, M.P.H. (University of Michigan), Kerry Ryan, M.A. (University of Michigan), Kunal Sanghavi, MBBS, M.S., C.G.C. (The Jackson Laboratory for Genomic Medicine), Kayte Spector-Bagdady, J.D., M.B.E. (University of Michigan), Alyx Vogle, M.S., C.G.C. (Brigham & Women's Hospital), and Charles Lee, Ph.D., FACMG (mPI; The Jackson Laboratory for Genomic Medicine). Special acknowledgment to Jon Reader, M.S., Michigan Alzheimer's Disease Center, University of Michigan, who assisted with data analysis. The consortium is supported by advisory board members Kyle Brothers, Ellen Wright Clayton, Patricia Deverka, Thomas Ellis, Aaron Goldenberg, Susan Mockus, Cynthia Casson Morton, Jens Rueter, and Brett Witham, along with stakeholder workgroup members Ethan Bessey, Erynn Gordon, LaTasha Lee, Jessica Roberts, and Fatima Saidi. The lead author (Ms. Willard) conducted this work as part of fulfilling degree requirements (master's thesis) for her master's degree in genetic counseling at the University of Michigan.

FUNDING INFORMATION

This study was funded by the National Human Genome Research Institute grant R01 HG010679. Dr. Blasco was supported by the National Human Genome Research Institute grant T32 HG010030.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST STATEMENT

Authors Willard, Uhlmann, Prince, Blasco, Pal, and Roberts each declare they have no conflicts of interest to disclose.

ETHICS STATEMENT

Human studies and informed consent: Approval of this human subjects research was obtained by the University of Michigan Health Sciences and Behavioral Sciences Institutional Review Board (IRB). All procedures followed were in accordance with the ethical standards of the University of Michigan's IRB (HUM00210267).

Animal studies: No non-human animal studies were carried out by the authors of this article.

Open Research

DATA AVAILABILITY STATEMENT

The authors will make relevant, unpublished short segments of data available to collaborators external to our team for the purposes of verifying or contextualizing the conclusions we have drawn in this publication. Any disclosure will be constrained by the need to protect the privacy of respondents. Requests should be sent to the corresponding author with a description of the reason for the request and the qualifications of those requesting the data.