Development and preliminary evaluation of a genetics education booklet for retinoblastoma

Abstract

Background

Parents and survivors of retinoblastoma often hold misconceptions about the disease and desire more extensive and detailed information about its genetic nature. The aim of this study was to co-develop and evaluate a genetic education booklet for retinoblastoma.

Methods

A human-centered design approach was employed, in which the study team consulted with clinician and patient knowledge user groups to design, produce, and refine an educational booklet. Over three phases of consultation, the study team met with each knowledge user group to review booklet prototypes and collect feedback for its further refinement. A preliminary evaluation using quantitative and qualitative methods was completed with six mothers of children with retinoblastoma.

Results

The iterative, phased design process produced an educational booklet rich in images and stories, with complex genetic topics described in simplified terms. The preliminary evaluation showed an average improvement in knowledge between pre- and post-test questionnaire of 10%. Participants were satisfied with content and comprehensiveness of the information included in the booklet.

Conclusion

A novel educational tool for families affected by retinoblastoma was developed through collaboration with health care and patient knowledge users. Preliminary evaluation results indicate it is feasible to implement and study the booklet in a prospective, pragmatic trial to evaluate its efficacy.

What is known about this topic

- Genetic testing and formal genetic counseling for heritable cancer syndromes, like retinoblastoma, is rare in the African healthcare setting.

- There is a need to improve patient-facing health materials, particularly for genetics, yet studies show that the patient voice is rarely included.

- Our previous study revealed that Kenyan parents and survivors of retinoblastoma lacked complete understanding of their genetic diagnosis and demanded more comprehensive delivery of genetic counseling, including tangible resources to aid their understanding.

What this paper adds to the literature

- This paper describes the development and preliminary evaluation of a genetics educational booklet for families affected by retinoblastoma in Kenya.

- Patients were critical to the development of the educational resource, offering unique insight from the lived experience of being affected by heritable cancer in a low-and-middle income country context.

- In a preliminary evaluation, the genetics educational booklet improved knowledge and confidence in retinoblastoma genetics among parents of children with retinoblastoma, showing promise for future scale-up and formal evaluation.

1 BACKGROUND

Retinoblastoma (RB) is a childhood eye cancer which affects children worldwide, but has higher mortality rates in the African context (Dimaras et al., 2015; Selvarajah et al., 2021). RB is curable, with a ~96% survival rate observed in high-income countries like Canada (Selvarajah et al., 2021); in low-and-middle-income countries (LMICs), mortality remains high, but targeted research and capacity building efforts, such as those observed in Kenya are starting to change this (Dimaras et al., 2015). For example, the establishment of the Kenyan National RB Strategy (Hill et al., 2016), aimed at early RB detection and enhancing quality of care to improve patient outcomes, led to an increase in RB survival from 30% (Nyamori et al., 2012) to 70% (Namweyi Nandasaba, 2015). Given its curability, the World Health Organization has designated RB an index cancer in its Global Initiative for Childhood Cancer, aiming to improve survival to 60% by 2030.

As a heritable cancer syndrome, high-quality genetic testing is essential for comprehensive diagnosis of RB. Predisposing RB1 pathogenic variants can be identified with 95% sensitivity for RB patients (Rushlow et al., 2009) and testing for these variants has been found to be cost-effective in North American settings (Noorani et al., 1996). Early prediction of disease, facilitated by genetic testing in at-risk infants, prompts early and frequent screening to treat tumors as soon as they appear (Dimaras et al., 2015). This leads to better visual outcomes with less intensive therapy (Soliman et al., 2016). Coupled with effective genetic counseling, genetic testing can also predict future cancer risk, and support at-risk individuals to undergo tailored follow up, access timely care, make informed lifestyle and family planning choices, and cope with diagnosis. However, genetic testing and formal genetic counseling for RB is mostly unavailable in the African healthcare setting. Researchers and policymakers agree that genetic services are becoming increasingly more relevant for improved health outcomes in LMICs (Tekola-Ayele & Rotimi, 2015).

There is a need to improve patient-facing health materials, particularly for genetics, yet studies show that the patient voice is rarely included (Wynn et al., 2018). We conducted a series of focus groups with survivors and parents of children with RB (Gedleh et al., 2018), propelled by evidence showing that studying patient perspectives can inform the design of genetic services (Adedokun et al., 2015; Gillham et al., 2015). Our previous study revealed that Kenyan parents and survivors of RB lacked complete understanding of their genetic diagnosis, and demanded more comprehensive delivery of genetic counseling, including tangible resources to aid their understanding (Gedleh et al., 2018). The work described in this study is a direct response to this request from the patient community. The goal of this study was to co-develop, with patient families, a genetics educational booklet for retinoblastoma and demonstrate proof-of-concept for its future evaluation in a real-world study.

2 METHODS

2.1 Phase I: Development of educational booklet

In the first phase of the project, the study team consulted with health care and patient knowledge user groups to design, produce and refine the educational booklet. Phase I took place from May to August of 2018.

2.1.1 Knowledge user recruitment and selection

Healthcare knowledge users included: physicians (ophthalmologists or oncologists), nurses, support group leaders (counselors), and cancer advocacy group representatives. Patient knowledge users included parents of children with RB and survivors of RB. Knowledge users were identified and recruited from Kenyatta National Hospital (KNH; Nairobi, Kenya), the University of Nairobi (UoN; Nairobi, Kenya) PCEA Kikuyu Hospital (KH; Kikuyu, Kenya), and Moi Teaching Referral Hospital (MTRH; Eldoret, Kenya). Patient knowledge users were modestly compensated for their time with provision of refreshments during the consultations and reimbursement for travel where appropriate.

2.1.2 Design of educational booklet

A human-centered design approach was employed to iterate the content and design of the educational booklet. Over three rounds of consultation, the study team met with knowledge users to review booklet prototypes and collect feedback for its further refinement. In Round 1, consultations were focused on determining the optimal content for the booklet. Knowledge users were asked to suggest the broad categories of information (e.g., diagnosis, treatment, cancer genetics, and genetic testing) that they preferred to include. Knowledge users were asked to consider these informational needs against the quantity of information, with an eye towards avoiding reader overwhelm. In Round 2, consultations were focused on developing figures and images that could convey key messages with ease to the patient audience. Initial designs were sketched by a graphic design student at the University of Nairobi, instructed to create images that were relevant and relatable to a Kenyan audience. Round 3, the final phase of consultation, was focused on refining the language of the booklet, with the aim of reducing the quantity of text without losing important content. Language was reviewed first in English and a Swahili version was created by translating from the English text. A final review of the resultant booklet was performed with patient and health care knowledge users to informally assess their views on the final product. Knowledge users in the final review were given the option to review either the English or Swahili version of the booklet and asked to suggest how the booklet might be implemented and evaluated.

2.2 Phase II: Preliminary evaluation of educational booklet

In the second phase of the project, a preliminary evaluation was conducted to assess the educational booklet's impact on knowledge change and its suitability for real-world use. Phase II occurred from September to December of 2018, and the methods below reflect suggestions provided by Phase I knowledge users.

2.2.1 Participant recruitment and selection

Parents or caregivers of children with RB who could communicate in English were eligible for the preliminary evaluation. Individuals who were involved in Phase I were excluded. For the ease of recruitment and to facilitate a rapid preliminary evaluation, participants were recruited only at KNH and a convenience sample was sought. Participants were modestly compensated for their time with provision of refreshments during the research activities and reimbursement for travel where appropriate.

2.2.2 Evaluation

The preliminary evaluation was composed of a quantitative knowledge test and qualitative focus group discussion. A pre- and post-test questionnaire (18 short answer and multiple-choice questions) assessed baseline knowledge and changes immediately after independent review of the booklet (for participants with visual impairment or blindness, a study team member read the content of the booklet aloud). Test questions focused on clinical characteristics of RB (five questions), definitions of genes and cancer (five questions), genetic origins and heritability of RB (three questions), and implications of RB genetics (five questions). Participants also provided information regarding their relationship to RB, perceived knowledge and confidence about RB, and whether or not they would use the booklet. Data were analyzed by basic descriptive statistics and changes in pre–post scores by paired Student t-test where possible. The focus group discussion aimed to glean: thoughts on the booklet's content, length, design, and desired changes; perceived change in knowledge, confidence about RB genetics, and remaining questions; and planned use of the information in health-related decision making. The discussion was audio recorded and transcribed, then evaluated using a descriptive content analysis.

2.3 Research ethics

Phase I was exempt from Research Ethics Board approval as it was not a research activity, but development of an intervention with knowledge users. Ethical approval for Phase II was obtained from the University of Nairobi (Protocol #UP704/10/2018). Written informed consent was obtained from all participants in Phase II.

3 RESULTS

3.1 Phase I: Development of educational booklet

3.1.1 Knowledge users

Fifteen healthcare knowledge users and five patient knowledge users participated in three to five consultations each. Table 1 shows demographic details of the knowledge user groups.

| Knowledge users (n = 20) | n | % |

|---|---|---|

| Healthcare | 15 | 75 |

| Role | ||

| Physician | 8 | 53 |

| Nurse | 4 | 27 |

| Counselor | 2 | 13 |

| Advocate | 1 | 7 |

| Affiliation | ||

| Hospital | 11 | 73 |

| Advocacy Group | 3 | 20 |

| Ministry of Health | 1 | 7 |

| Patient | 5 | 25 |

| Role | ||

| Parent/Guardian | 5 | 100 |

| Survivor | 0 | 0 |

3.1.2 Booklet content and design

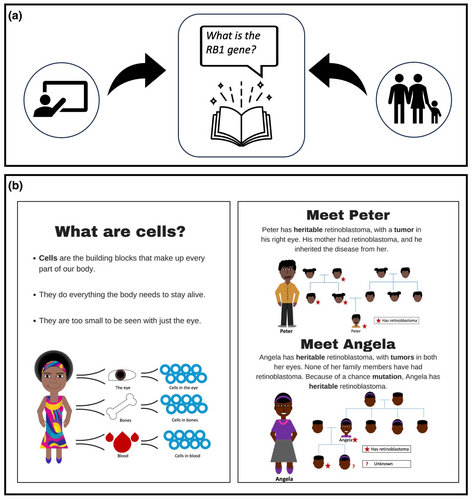

An iterative, phased design process produced an educational booklet rich in images and stories, with complex genetic information described in lay language. The images show cartoon families visiting doctors, and simplified diagrams of cells and genes (Figure 1). The booklet employs characters and stories to explain the nuances of heritable and non-heritable RB. Core concepts covered in the booklet include: definitions of DNA, genes, cells, and pathogenic variants; cancer development; the genetic development of RB and inheritance patterns; consequences of heritable RB versus non-heritable RB; and treatment. The booklet also tackles common myths about the origins of cancer (i.e., witchcraft or curse) to curb the stigma associated with heritable cancer.

3.1.3 User guide

An unexpected result of our knowledge user-directed process was that the knowledge users suggested the educational booklet be used in two ways: (1) as a take home for patient families (as initially anticipated); and (2) in educational sessions led by trained facilitators (e.g., nurses, counselors, and patient navigators), according to directions found in a user guide (Figure 1). A user guide was therefore designed to include suggested language for explaining concepts in the booklet, discussion points, and additional (non-essential) information to cover, depending on level of patient understanding. The user guide also instructed clinicians on how to employ a ‘teach-back’ method to check for patient understanding. The intention is to promote dialogue between health professionals and patients that eliminates confusion, a feature supported by the literature (Noorani et al., 1996; Rushlow et al., 2009). Knowledge users also suggested that the content of booklet could be printed as a large format flipchart, to better serve as a visual aid during the educational sessions.

3.2 Phase II: Preliminary evaluation of educational booklet

3.2.1 Participants

The final educational booklet was reviewed by six mothers of children undergoing treatment for RB at KNH; one mother was also a blind survivor of RB. Three of the six additionally participated in the knowledge evaluation.

3.2.2 Quantitative results

Average knowledge scores improved from 67% pre-test to 83% post-test for the two unaffected mothers (p < 0.001) (Table 2). The one survivor/parent scored 83% on both tests. Categories of questions that showed improvement were definitions of genes and cancer and genetic origins and heritability of RB (Table 3). All participants (3/3) reported that the booklet improved their knowledge and rated their confidence level as “Good” in making decisions about their affected child. When asked if they would share the booklet with family or community members, they all answered “Yes” and gave reasons including changing the thinking around RB and supporting early detection.

| Participant | Pre-test score | Post-test score | p Value | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n | % | n | % | ||

| Parents | |||||

| Participant 1F | 12 | 67 | 15 | 83 | <0.0001 |

| Participant 3F | 12 | 67 | 15 | 83 | |

| Survivor/parent | |||||

| Participant 2F | 15 | 83 | 15 | 83 | – |

| Participant | Pre-test | Post-test | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Correct | Incorrect | No answer | Score (%) | Correct | Incorrect | No answer | Score (%) | |

| Parents | ||||||||

| Participant 1F | ||||||||

| Clinical characteristics of RB (/5) | 5 | 0 | 0 | 100 | 5 | 0 | 0 | 100 |

| Definitions of genes and cancer (/5) | 0 | 2 | 3 | 0 | 2 | 1 | 2 | 40 |

| Genetic origins and heritability of RB (/3) | 2 | 0 | 1 | 67 | 3 | 0 | 0 | 100 |

| Implications of RB genetics (/5) | 5 | 0 | 0 | 100 | 5 | 0 | 0 | 100 |

| Participant 3F | ||||||||

| Clinical characteristics of RB (/5) | 5 | 0 | 0 | 100 | 5 | 0 | 0 | 100 |

| Definitions of genes and cancer (/5) | 1 | 0 | 4 | 20 | 3 | 0 | 2 | 60 |

| Genetic origins and heritability of RB (/3) | 2 | 0 | 1 | 67 | 3 | 0 | 0 | 100 |

| Implications of RB genetics (/5) | 4 | 1 | 0 | 80 | 4 | 1 | 0 | 80 |

| Survivor/parent | ||||||||

| Participant 2F | ||||||||

| Clinical characteristics of RB (/5) | 5 | 0 | 0 | 100 | 5 | 0 | 0 | 100 |

| Definitions of genes and cancer (/5) | 2 | 2 | 1 | 40 | 2 | 1 | 2 | 40 |

| Genetic origins and heritability of RB (/3) | 3 | 0 | 0 | 100 | 3 | 0 | 0 | 100 |

| Implications of RB genetics (/5) | 5 | 0 | 0 | 100 | 5 | 0 | 0 | 100 |

3.2.3 Qualitative results

It has given us a lot of information, because at first I thought it [retinoblastoma] was maybe witchcraft. In fact when they told me it was about genetics, I was asking myself, I have never heard of this in my family. And I was asking why, my baby? And so now, I have gotten this information from this booklet. (Participant 1F)

After I have gone through the booklet, I would like to know more about the second cancers. I didn't understand. And can the baby be screened for retinoblastoma in the womb? Is it possible? (Participant 1F)

-

- Participant 5F

-

- I think you caninclude, which food can we eat, or how can we treat it by what we eat. We want to know what we can do ourselves.

-

- Participant 2F

-

- And what food to avoid.

When you see your child is improving from medication and treatment, you will remember the booklet. So then you think, okay this kid can be a cancer survivor. And you can go ahead educating someone. (Participant 2F)

It is important to encourage mothers who are worrying. (Participant 4F)

-

- Participant 2F

-

- They [retinoblastoma families] don't have any hope. If they come to hospital they would be depressed. Even if they had the booklet it wouldn't help because they wouldn't have any hope.

-

- Facilitator

-

- Then in that case, how could the booklet include support you could access?

-

- Participant 2F

-

- Yes it could include counselling or financial support.

It is helpful, because we are gaining insight in this discussion about the booklet. We are learning things we didn't know. (Participant 2F)

4 DISCUSSION

Genetic testing and counseling are essential for cancer care (American Society of Clinical Oncology, 2003), but availability, access, and quality varies worldwide (Hawkins & Hayden, 2011; He et al., 2014; Hill et al., 2015). This is in part attributable to a false impression by funders and policymakers that genetic services are irrelevant for LMICs (Wonkam et al., 2010). Where genetic services do exist, it is predicted that they will soon be unable to meet their increasing demand (Trepanier & Allain, 2014). With increasing demand for cancer genetic services in LMICs like Kenya, new models of service delivery are needed (Trepanier & Allain, 2014). Specifically, these models should take in to account the unique ethical, social, and cultural context of the setting they are being designed for (Zhong et al., 2021). Our prior work defined a model for delivery of clinical genetic services in Kenya that emphasized the need to develop novel educational tools, and a patient- and community-centered approach to genetic counseling (He et al., 2014). Our current study represents a novel patient-oriented approach to begin identifying and addressing such issues while filling the gap in genetic counseling services in Kenya. Furthermore, by focusing the work on the prototypic heritable cancer RB, our results have wide relevance and applicability to the many countries, inclusive of LMICs and also HICs, currently shaping childhood cancer policy to improve RB outcomes and quality of life.

Comprehensive understanding of RB and its heritable consequences is important so that appropriate interventions, such as regular eye examinations for at-risk infants, are sought out early enough to save lives and vision. The educational booklet described in this manuscript showed promise in meeting this aim, as it was developed in direct consultation with the patient community. As a result, the educational booklet contains the content that families want and need to know, described in an understandable format. The combination of factual content and stories used in the resultant booklet has been proven effective in relaying health information (Kitamura et al., 2011) and communicating difficult concepts to patients and families with low literacy (Houts et al., 2006). Furthermore, the images and language choices, particularly in the Swahili version of the booklet, were tailored to the cultural context of Kenya. Yet, even with these culturally specific nuances, the broader content in the booklet has potential applicability to other geographic or cultural regions struggling with communicating information about heritable cancer.

Genetic diagnoses place a significant psychosocial burden on families (Eijzenga et al., 2014; Wonkam et al., 2014). Culture and society can influence how people interpret genetic health information (Solomon et al., 2012). Thus, engaging patients in designing genetic counseling interventions is important so that innovations are useful and relevant. However patient engagement is challenging in the LMIC context (Janic et al., 2020); while we were able to recruit 11 patient partners, we did not achieve a 1:1 ratio of patients to non-patients recommended for such work. Importantly however, the patients who did participate were able to provide important insights into the local context, particularly the need for financial support and psychosocial counseling to support the uptake of genetic information. Also of note, one participant indicated that they would share the booklet with friends and family to reduce stigma around cancer, which is prevalent in the Kenyan context. The issue of stigma is increasingly being reported in North American context as more diverse populations are being included in research about disclosure of genetic results to family (Hunter et al., 2023).

Another outcome of our knowledge user-guided process was the development of a user guide to assist health professionals in leading counseling sessions. This was suggested by health care knowledge users, noting that they required more support in information delivery; the user guide was suggested with the intention to help standardize the delivery of genetic information, particularly in a context where genetic counselors are rare. In our evaluation, the user guide and educational session were not evaluated, but instead the booklet was independently reviewed by participants. An educational session intervention would need to be developed and tested in future. Previously, to address the challenge of scarce genetic counselors in Kenya, we implemented and tested a role-play based workshop to improve health professional understanding and skills regarding genetic counseling for RB (Hill et al., 2015). This workshop could be modified to train facilitators on the use of the booklet and user guide. Encouragingly, there are more and more formal programs starting to introduce genetic counseling in sub-Saharan Africa through twinning, for example, in Ethiopia (Quinonez et al., 2021).

The preliminary intervention has shown promise in improving knowledge and confidence in RB genetics among parents of children with RB. Interestingly, the booklet inspired new questions on screening for second cancers and prevention of RB, which are key research questions yet to be solved globally. Importantly, it also revealed that it could be improved to better articulate the limited evidence on the role of environmental factors, such as diet, on RB development, to alleviate worry or guilt in parents.

Genetic testing can identify the precise pathogenic variant carried by a proband, the discovery of which is essential to predict the cancer in at-risk family members or confirm non-heritable RB status. The Kenyan Ministry of Health guidelines for RB care (Ministry of Health Kenya, 2014) include recommendations for genetic testing and counseling; however, since few Kenyan families have been able to access RB genetic testing (via North American or European laboratories, paying out of pocket), most patients are counseled by their clinician based on their phenotype or known family history of disease. Therefore, the educational booklet was designed and tested in the current context of the absence of genetic testing for RB. However, the original study that indicated a need for more education also indicated that patients want improved availability and access to genetic testing—motivated by the idea of preventing or minimizing the effects of the cancer on future generations (Gedleh et al., 2018). Even the patients in the current research had questions about prenatal detection and early intervention, though it is currently only available in the European (Gerrish et al., 2019) and North American (Soliman et al., 2016) contexts. Yet, questions like the ones from the patients in this study, as well as research on other heritable cancers in other parts of Africa, indicate that cancer genetic services are desired by the patient community; a study from Nigeria even showed that cancer patients are willing to pay out of pocket for cancer genetic testing (Adejumo et al., 2023).

We note that the main limitation of our evaluation was the small sample in Phase II, a result of limited time and funding. Given these anticipated logistical constraints, the study team set out to conduct a small preliminary study to gauge the feasibility of proceeding with a larger-scale evaluation. Moreover, the small sample size provided an unexpected opportunity for the study team to assess how patient engagement could be enhanced, actively involving parents or survivors as partners in the future evaluation; these insights have been presented in our published model for patient engagement in LMICs (Janic et al., 2020). Embedding patient partners into our study team is expected to facilitate recruitment and retention of a sufficient sample size in future study (Chhatre et al., 2018).

In summary, our preliminary evaluation indicated feasibility of future implementation and formal evaluation of the booklet for its efficacy in increasing knowledge and health decision making regarding RB genetics. Patients were critical to its development and offering unique insight from the lived experience of being affected by heritable cancer in the Kenyan context. Given that genetic testing for RB is being developed now for Kenya, the current intervention could be expanded to include a patient-facing genetic testing report to aid counseling sessions for those who have undergone testing.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

All authors meet the 4 ICJME criteria as follows: Conception or design of the work (HD) or acquisition, analysis, or interpretation of data for the work (all authors); drafting the work (TI, MB, AH, and HD) or reviewing the work critically for important intellectual content (KK, JK, FN, LN); final approval of the version to be published (all authors); and agreement to be accountable for all aspects of the work (all authors). Author HD confirms that she had full access to all the data in the study and takes responsibility for the integrity of the data and the accuracy of the data analysis. All of the authors gave final approval of this version to be published and agree to be accountable for all aspects of the work in ensuring that questions related to the accuracy or integrity of any part of the work are appropriately investigated and resolved.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The authors wish to acknowledge the contributions of all knowledge users for their time and input into the development of the educational booklet. Authors TI, MB, and AH completed this work as part of their undergraduate degree requirements and were supported by the Queen Elizabeth II Diamond Jubilee Foundation Scholarship program, which included a research allowance that was used to support project activities.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST STATEMENT

The authors have no conflicts to disclose.

ETHICS STATEMENT

Human studies and informed consent: This study adhered to the principles set out in the Declaration of Helsinki. Phase I was exempt from Research Ethics Board approval as it was not a research activity, but development of an intervention with knowledge users. Ethical approval for Phase II was obtained from the University of Nairobi (Protocol #UP704/10/2018). Written informed consent was obtained from all participants in Phase II.

Open Research

DATA AVAILABILITY STATEMENT

De-identified data may be made available upon reasonable request sent to corresponding author.