Impacts of genesurance considerations on genetic counselors' practice and attitudes

Abstract

Genesurance counseling has been identified as an integral part of many genetic counseling sessions, but little is known about the workflow impacts and genetic counselor perceptions of genesurance-related tasks. In this study, we aimed to characterize how insurance and billing considerations for genetic testing are being incorporated into genetic counselors' practice in the United States, as well as describe current attitudes and challenges associated with their integration. An electronic survey was sent by email to members of the National Society of Genetic Counselors (NSGC). A total of 325 American Board of Genetic Counselors-certified genetic counselors who provide direct patient care in the United States for at least 50% of their time were included in data analysis. Results showed that the frequency and timing of various insurance- and billing-related tasks were not consistent among respondents, even those practicing in similar settings. Inadequate training to complete tasks was reported by 64% of respondents, and 47% reported a lack of resources from their employer and/or institution to complete genesurance tasks. Additionally, only 38% of respondents agreed that insurance- and billing-related tasks were within the scope of the genetic counseling practice, and there was little consensus on who respondents believe is the most appropriate person to complete these tasks. When asked how genesurance considerations affected job satisfaction, 85% of respondents reported a negative impact. This study found an inconsistent genesurance workflow among genetic counselors practicing in the United States, a lack of consensus on who should be responsible for genesurance tasks, several challenges associated with completing these tasks, and identifies genesurance considerations as potential risk factors for genetic counselor burnout.

1 INTRODUCTION

Due to advancements in genetic testing technologies and increased awareness of clinical applications of this testing, more patients are being offered genetic testing as a part of their medical care (Kotzer et al., 2014). However, uptake of these tests often depends on the ability to obtain insurance coverage (Prince, 2015). Recent studies have identified multiple insurance- and billing-related barriers to coordinating genetic testing, including cumbersome preauthorization processes, inconsistent coverage by payers, and insufficient staffing to complete insurance and billing tasks (Kutscher, Joshi, Patel, Hafeez, & Grinspan, 2017; Uhlmann, Schwalm, & Raymond, 2017). Patient decision-making regarding genetic testing is also influenced by insurance coverage, and many patients chose not to proceed with genetic testing due to lack of coverage and cost of testing (Hayden, Mange, Duquette, Petrucelli, & Raymond, 2017).

Given that insurance and billing factors play a role in patient decision-making, discussion of these issues is viewed by many clinicians as part of the informed consent process for genetic testing (Hooker et al., 2017; Riggs & Ubel, 2014), more recently referred to as ‘genesurance’. Genesurance counseling was first defined in the literature as the part of a genetic counseling session dedicated to discussing costs and insurance coverage of genetic testing (Brown et al., 2017). This same study focused on how genetic counselors perceived their role in regard to insurance and financial topics reported that 99% of genetic counselors discuss insurance and billing with their patients and 85% of genetic counselors viewed genesurance counseling as a part of their role (Brown et al., 2017). A second study focusing on patient expectations reported that a majority of patients expect genesurance counseling during a genetic counseling session (Wagner et al., 2018).

While genesurance discussions take place during a genetic counseling session, insurance and billing considerations also influence genetic counselors' workflow outside of sessions, especially when coordinating genetic testing (Hooker et al., 2017). Many of the tasks necessary to complete genetic testing are multi-step and time-consuming processes (Uhlmann et al., 2017). Insurance coverage for genetic testing often varies between payers, plans, and testing indications, which leads to complications in healthcare navigation for both the genetic counselor and the patient (Lu et al., 2018; Prince, 2015). In addition, one study found that 74% of genetic counselors reported that insurance-related issues directly changed their practice dynamics (Brown et al., 2017). The nature of these reported changes was not investigated at that time.

Despite the evidence that the vast majority of genetic counselors are incorporating genesurance into their practice, the impacts of its incorporation into the practice, especially those tasks that occur outside of patient-facing session time, have not been well characterized. The first aim of this study was to describe the impacts of genesurance considerations related to genetic testing on genetic counselors' workflows, specifically in regard to the frequency and timing that genetic counselors are completing genesurance-related tasks. The second aim was to assess current attitudes toward the incorporation of genesurance-related tasks into the genetic counseling practice. By characterizing this, we hope to identify the challenges associated with insurance and billing tasks in the genetic counseling practice and determine possible ways to address and alleviate these challenges for current and future genetic counselors.

2 METHODS

This study was approved by the Institutional Review Board at UT Health (HSC-MS-18-0493).

2.1 Participants

Board-certified genetic counselors practicing in the United States of America who spoke English and who reported spending at least 50% of their time counseling patients in person or via telemedicine were eligible to participate in this study. Screening questions at the beginning of the survey ensured participants met eligibility criteria for participation in the study; all others were excluded.

2.2 Instrumentation

An electronic survey with a total of 28 questions was developed by the authors based on anecdotal experience and prior studies regarding genesurance. It was initially piloted to a group of six genetic counselors across a variety of specialties and then distributed via the Qualtrics platform (Qualtrics, Provo, UT). Survey respondents remained anonymous. To meet the aims of this study, questions were developed and presented in one of three domains: demographics, workflow, and attitudes. Workflow questions related to the objective aspects of insurance and billing tasks included timing, frequency, and resources utilized. Attitude questions related to the subjective aspects of insurance and billing tasks included job satisfaction, perceived patient impact, and confidence. A free response question asked respondents to identify and describe, if any, challenges they have faced incorporating genesurance into their workflow. A second free response question asked respondents who reported practicing in multiple specialties to describe any perceived differences in billing and insurance considerations between their specialties. The full survey is available in the Supporting Information.

2.3 Procedure

Eligible counselors were invited to participate via an email distributed through the National Society of Genetic Counselors (NSGC) listserv, reaching approximately 4,000 genetic counselors, students, and other healthcare professionals. The survey was accessible from August 8, 2018, to September 31, 2018. Participants were not required to complete the survey in its entirety or during a single session. Informed consent was obtained by participants prior to initiation of the survey.

2.4 Data analysis

Survey results were collected in Qualtrics and coded into a Microsoft Excel file stored on a secure server. All eligible respondents who completed at least 50% of the survey beyond the demographics portion of the survey were included in data analysis. Data were analyzed with Stata (v.13.0), and statistical significance was assumed at type I error rate of 5% (p < .05). Descriptive statistics were produced using frequencies and percentages for categorical variables and means and standard deviations for continuous variables. Any group containing over 50% of respondents was considered the majority group. Chi-square analysis was used to determine significant associations between variables. As multiple chi-square analyses were performed, a Bonferroni correction was calculated to control for familywise error rate for 25 analyses, resulting in an adjusted significant p-value of p < .002. For the purposes of our analysis, respondent-reported specialties were grouped into five major subcategories. Respondents who reported practicing in only one specialty were categorized as cancer, prenatal, pediatric, or other. The ‘other’ subcategory included respondents who reported working in only adult, cardiology, industry, infertility/preconception, metabolic, molecular/cytogenetics, neurology, or primary care genetics. Respondents who reported in working one or more specialty were categorized as ‘multiple specialties’ and could include any combination of the above specialties.

Analysis of free responses was completed using content analysis in which each response was independently categorized into one or more identified themes by the primary author ET and author LM (Bengtsson, 2016). Thematic coding of each response was subsequently compared and agreed upon by both authors.

3 RESULTS

3.1 Demographics

A total of 369 eligible individuals initiated the survey. Respondents who completed only the demographics section (n = 40) and respondents who completed <50% of the survey beyond the demographics section (n = 4) were excluded, resulting in a total of 325 respondents included in the data analysis. As not all participants completed the survey in full, questions have varying response rates. Based on data from the 2018 NSGC Professional Status Survey (National Society of Genetic Counselors, 2018a) indicating 59% of counselors work in direct patient care positions, and the approximate number of members on the NSGC listserv at the time of survey distribution, the overall response rate of eligible participants was approximately 325/2,360 (13.8%).

Demographic data of respondents are outlined in Table 1. Each of the six NSGC regions was represented by the respondents. Experience level, as indicated by years as a practicing certified genetic counselor, varied among respondents with the highest proportion of respondents (151/325, 46.5%) reporting 1–4 years as a practicing genetic counselor. Most respondents reported working in one of three primary work settings: academic institution (135/325, 41.5%), private hospital or facility (96/325, 29.5%), and public hospital or facility (76/325, 23.4%). Respondents were asked to identify all specialties in which they work, of which 39.1% (127/325) reported working in multiple specialties. Cancer was the most frequently reported specialty, with 49.2% (160/325) of respondents reporting working in a cancer setting in some capacity. Prenatal (98/325, 30.2%) and pediatrics (97/325, 29.8%) were the next most frequently reported specialties, respectively.

| n | (%) | |

|---|---|---|

| NSGC region (n = 325) | ||

| 1 | 21 | 6.5 |

| 2 | 65 | 20.0 |

| 3 | 48 | 14.8 |

| 4 | 102 | 31.4 |

| 5 | 47 | 14.5 |

| 6 | 42 | 12.9 |

| Years practicing (n = 325) | ||

| <1 year | 31 | 9.5 |

| 1–4 years | 151 | 46.5 |

| 5–10 years | 77 | 23.7 |

| Over 10 years | 66 | 20.3 |

| Primary work setting (n = 325) | ||

| Academic institution | 135 | 41.5 |

| Private facility | 96 | 29.5 |

| Public facility | 76 | 23.4 |

| Laboratory | 10 | 3.1 |

| Research | 1 | 0.3 |

| Other | 7 | 2.2 |

| Specialty (n = 325) | ||

| Cancer genetics | 160 | 49.2 |

| Prenatal | 98 | 30.2 |

| Pediatric | 97 | 29.8 |

| Adult | 57 | 17.5 |

| Cardiology | 38 | 11.7 |

| Infertility/Preconception | 32 | 9.9 |

| Neurogenetics | 26 | 8.0 |

| Metabolic diseases | 24 | 7.4 |

| Laboratory testing | 11 | 3.4 |

| Other | 9 | 2.8 |

| Industry | 4 | 1.2 |

| Primary care | 3 | 0.9 |

| Multiple specialties | 127 | 39.1 |

3.2 Practice

3.2.1 Frequency and timing of tasks

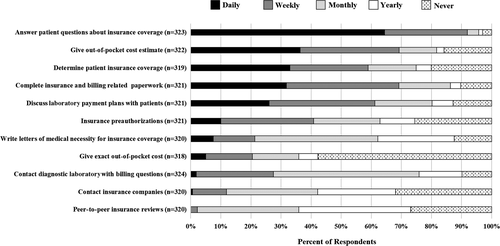

Respondents were asked to identify the frequency and timing of several billing and insurance tasks they may perform in relation to genetic testing. Figure 1 outlines the specific tasks and frequency reported for each task. The most frequently performed task was answering patient questions about insurance coverage with over 90% (297/323) of respondents performing this task at least weekly. Additionally, a majority of participants reported performing the following tasks at least once per week: giving estimated out-of-pocket estimates (223/322, 69.3%), completing insurance- and billing-related paperwork (222/321, 69.2%), discussing laboratory payment plans with patients (196/321, 61.1%), and determining patient insurance coverage (188/319, 58.9%). The least frequently performed task was peer-to-peer insurance reviews with 97.8% (313/320) of respondents performing this task less than once per week. Other tasks performed less than weekly by a majority of respondents include the following: insurance preauthorizations (190/321, 59.2%), contacting diagnostic laboratories with insurance- and billing-related questions (198/322, 61.5%), writing letters of medical necessity for insurance coverage (252/320, 78.8%), giving exact out-of-pocket cost estimates (252/318, 79.2%), and contacting insurance companies with questions (282/320, 88.1%).

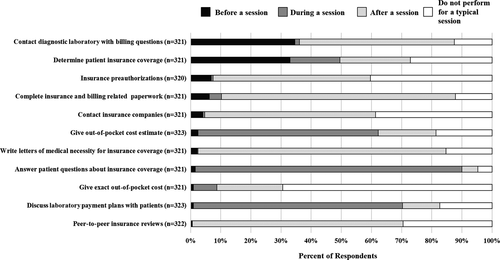

The time at which these tasks are typically completed in relation to the genetic counseling session is summarized in Figure 2. The majority of respondents reported answering patient questions about insurance coverage (284/321, 88.5%), discussing laboratory payment plans with patients (224/323, 69.3%), and giving out-of-pocket cost estimates (193/323, 59.8%) as being performed during the genetic counseling session. Contacting the diagnostic laboratory with insurance and billing questions (165/321, 51.4%), calling insurance companies with questions (182/321, 56.7%), insurance peer-to-peer reviews (225/322, 69.9%), completing insurance- and billing-related paperwork (249/321, 77.6%), and writing letters of medical necessity for insurance coverage (264/321, 82.2%) were reported as being performed after the genetic counseling session by a majority of counselors. The majority of respondents reported never providing exact out-of-pocket costs (223/321, 69.5%) and determining patient insurance coverage was most commonly reported as occurring before the genetic counseling session (106/321, 33.0%).

Respondents reported when they initiated genesurance discussions with patients during a typical genetic counseling session. The majority of respondents (207/325, 63.7%) discuss these considerations after explaining testing options but before a patient has elected genetic testing and 24.9% (81/325) of respondents reported talking to patients about billing and insurance factors after the patient has elected genetic testing. Discussing these factors before discussing genetic testing or only if the patient brings it up were reported by 4.3% (14/325) and 4.6% (15/325) of respondents, respectively, and 2.5% (8/325) of respondents do not discuss insurance and billing considerations during a typical session.

3.2.2 Laboratory selection

Over 90% (296/324) of respondents reported that multiple insurance and billing factors influenced their choice of genetic testing laboratory. When asked to choose the factor that most heavily influences their choice, 23.7% (76/321) chose the patient's out-of-pocket cost for testing. The patient's in-network insurance coverage was indicated by 18.4% (59/321) of respondents as the most influential factor, and 15.9% (51/321) indicated the availability of a cost notification threshold. The cost of a patient self-pay option (28/321) was cited by 8.7% of respondents, and laboratory performed preauthorizations (27/321) and institutional contracts (27/321) were each cited by 8.4% of respondents as being the most influential consideration. Availability of out-of-pocket cost estimates was selected by 6.5% (21/321) of respondents, and laboratory financial assistance plans were selected by 2.8% (9/321) of respondents. Other factors not specified by the survey were cited by 3.7% (12/321) of respondents, and 3.4% (11/321) of respondents did not send out genetic testing.

The most frequently selected influential factors in selecting a diagnostic laboratory were the availability of an out-of-pocket cost estimate for the patient, in-network coverage of laboratories, and the availability of a cost notification to the patient. Financial assistance programs offered by the laboratory, patients exact out-of-pocket cost for a test, institutional contacts with laboratories, and ‘other’ were less frequently selected by respondents. A chi-square test of independence was performed to examine the relationship between specialty (categorized as cancer, prenatal, pediatric, multiple specialties, or other) and selection of most influential factors in selecting a laboratory, and this relationship was significant (χ2 (32, N = 321) = 106.54, p < .001). Individuals who only practice in cancer were more likely to choose the availability of cost notification (29.9%) or self-pay as their most influential factor (28.9%). Individuals who only practice in prenatal were more likely to choose laboratories in-network with their patient's insurance as their most influential factor (32.6%). Individuals practicing in pediatrics were more likely to select out-of-pocket cost (20.0%) and whether or not their institution had a contract with the diagnostic laboratory (20.0%) as their most influential factors.

3.3 Differences between specialties

Just over one-third (127/325, 39.1%) of respondents reported working in multiple specialties. Of those respondents, 48.8% (62/127) reported that there were differences in insurance and billing considerations between specialties. Free responses describing variation between specialties were provided by 54/62 (87.1%) of respondents who reported differences between their specialties. Six themes emerged encompassing differences in: insurance and billing processes (30/54, 55.6%), availability of genetic testing guidelines (17/54, 31.5%), availability of billing staff (9/54, 16.7%), importance of insurance coverage for testing (6/54, 11.1%), patient population (5/54, 9.3%), and time restrictions on testing (2/54, 3.7%). Some responses were assigned more than one theme.

3.4 Attitudes

3.4.1 Training and resources

When asked whether they were confident in their abilities to complete insurance- and billing-related tasks, 75.7% (237/313) of respondents agreed that they felt confident, while 24.3% (76/313) of counselors did not feel confident. Most counselors (305/324, 94.1%) reported the use of multiple resources while performing insurance and billing tasks, including past experience (269/324, 83.0%), the performing laboratory's self-pay price of a test (262/324, 80.9%), the performing laboratory's billing department (212/324, 65.4%), colleagues (208/324, 64.2%), insurance company policies, websites, or phone support (165/324, 50.9%), the performing laboratory's online cost estimation tool (140/324, 43.2%), and institutional billing support (124/324, 38.3%). Overall, a perception of adequate access to resources was reported by 52.9% (165/312) of genetic counselors.

Although 76.0% (247/325) of respondents reported learning about insurance and billing in multiple settings, reporting multiple learning settings was not associated with reported confidence (χ2 (1, N = 311) = 4.59, p = .032). The majority of participants cited self-guided or on the job learning (318/325, 78.8%), a lecture in graduate school (169/325, 52.8%), and clinical experience in graduate school (189/325, 58.9%) as learning settings. Self-guided or on the job learning was the only learning setting reported by 23.4% (76/325) of respondents. Employer provided training (44/325) and opportunities through professional societies (43/325) were cited by 13.5% and 13.2% of respondents, respectively. Less than 1% (3/325, 0.9%) of respondents reported having a full course in graduate school. Overall, inadequate training to complete insurance and billing tasks was reported by 63.8% (199/312) of respondents.

3.5 Scope

Participants were asked to indicate whether they believed insurance and billing considerations outside of direct patient counseling were within the scope of the genetic counseling practice. Responses showed that 38.2% (120/314) of participants agreed that these tasks were within the scope of practice, 35.0% (110/314) disagreed, and 26.8% (84/314) were unsure. A chi-square test of independence was performed to examine the relationship between specialty (cancer, prenatal, pediatrics, multiple specialties, or other) and whether or not participants felt genesurance tasks outside of direct patient interaction fell within the genetic counselor scope of practice (agree, disagree, unsure). The relationship between these variables was significant (χ2 (8, N = 314) = 27.09, p = .001). Cancer counselors were more likely to agree that these tasks fell within the scope of genetic counseling practice 52/96 (54%), while only 32.0% (31/97) of prenatal respondents and 29.0% (27/93) of pediatric respondents agreed with this statement. Counselors who practiced in multiple specialties were evenly split with 45/125 (36%) agreeing with this statement, 40/125 (32%) disagreeing with this statement, and 40/125 (32%) stating they were unsure if these tasks fell into the genetic counseling scope of practice. Finally, counselors who practiced in other specialties were more likely to disagree with this statement 10/16 (62.5%).

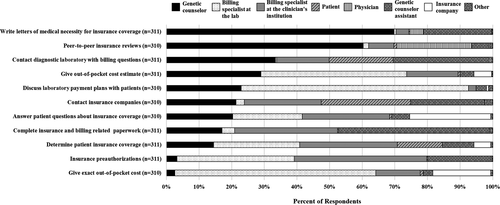

Additionally, respondents were asked to indicate the individual that they believed was the best person to manage each insurance and billing task (Figure 3). A majority of respondents believed that genetic counselors were the best individuals to complete letters of medical necessity (217/311, 69.8%) and perform peer-to-peer reviews (187/310, 60.3%). Less than 4% of respondents believed that genetic counselors were the best individuals for obtaining insurance preauthorizations (10/311, 3.2%) or providing exact out-of-pocket costs (8/310, 2.6%).

3.5.1 Job satisfaction

To assess the impact of insurance and billing factors on job satisfaction, respondents were asked to describe the impact on a five-point Likert scale. Responses were highly skewed toward a negative perception with 20.1% (63/313) reporting a significant negative impact and 64.9% (203/313) reporting a negative impact on job satisfaction. Only 1.9% (6/313) of respondents reported a positive impact, and 0.3% (1/313) reported a significant positive impact. Insurance and billing factors had no impact on job satisfaction for 12.8% (40/313) of respondents.

3.5.2 Patient interaction

Respondents were asked to describe the impact that insurance and billing considerations had on their patient interactions using a five-point Likert scale. Almost half (154/313, 49.2%) of respondents reported no impact on patient interaction. A negative impact was reported by 31.0% (97/313), and a significant negative impact was reported by 2.6% (8/313) of respondents. A positive impact was indicated by 15.3% (48/313) and a significant positive impact by 1.9% (6/313) of respondents.

3.6 Challenges

A majority (264/313, 84.3%) of respondents reported experiencing challenges in the incorporation of insurance and billing tasks into their genetic counseling practice. Respondents had the opportunity to elaborate on these challenges by responding to a free response question. A total of 189 of the 264 (71.6%) respondents described experiencing challenges in their free responses. Many responses encompassed more than one theme. From these responses, eleven themes emerged including the following: time management issues (87/189); inconsistent, complex, or confusing processes; restricts testing options or availability (76/189); negative impact on patient experience or management (51/189); impedes GC's ability to provide the highest quality care to patients (51/189); inadequate staffing or support (39/189); difficulty obtaining information needed to complete tasks from insurance companies, laboratories, or employers (38/189); inadequate training, knowledge, or resources to complete tasks (31/189); unethical utilization of healthcare dollars (6/189); institutional restrictions (4/189); and poor patient literacy (4/189), as summarized in Table 2. A complete compilation of free responses regarding challenges and their assigned themes is available for review in Supplementary Table 1.

| Theme | n | % | Excerpts |

|---|---|---|---|

| Creates time management issues | 87 | 46.0 |

‘Time consuming and takes up time for other clinical activities’ ‘The largest challenge I have faced is time management. While I feel capable of handling billing issues and preauthorizations they are incredibly time consuming’ ‘Balancing clinical and research work, along with other projects, with the unpredictable yet time-consuming legwork that goes into attempting to obtain insurance coverage for our patients, including to draft letters of medical necessity, coordinating and conducting peer-to-peer discussions, and preparing documents for appeals’ |

| Inconsistent, complex or confusing processes | 76 | 40.2 | ‘Insurance and lab policies seem to change all the time. Difficult to keep up with all of the updates and changes. And all of the exceptions to the rules that are in place’ |

| Restricts testing options or availability | 51 | 27.0 |

‘The quality of testing being done has also been a challenge because we are faced with the option of testing through a non-preferred laboratory or not testing at all for some cases’ ‘Billing considerations can significantly impact whether or not a patient can have appropriate genetic testing. I often have to spend a significant amount of time on billing/insurance related issues when considering which lab to use and sometimes [am] forced to go with, in my opinion, a sub-par lab simply because of their insurance. Also, the amount of time spent on doing this detracts from more pressing issues like patient care and preparedness for clinic’ |

| Negative impact on patient experience or management | 51 | 27.0 | ‘Me bringing up lack of coverage has added a negative cloud to some sessions that were otherwise going smoothly. I end up having to counsel patients through some of their feelings about their finances’ |

| Impedes ability to provide the highest quality care to patients | 51 | 27.0 |

‘It frustrates me that patients' different insurance plans mean they have unequal access to care. We can see two patients with the exact same clinical situation but the testing they are able to have is very different because of financial considerations’ ‘A significant portion of my time that I could be using for better patient care is dedicated to insurance-related tasks and follow up. We have also received an increasing number of denials for genetic testing from different insurance companies, which then takes more time from my practice with appeals and explaining self-pay options to patients’ |

| Inadequate staffing or support | 39 | 20.6 |

‘Our institution lacks administrative support and clear policies regarding insurance authorization for genetic testing’ ‘The billing representatives within my organization are even less equipped than I am to handle billing matters for genetic testing. Discussion of insurance and billing-related matters take up enormous amounts of time, and it is frustrating for patients when they are told they need to contact our billing team when our billing team bounces them right back to me as soon as they hear the word “genetic”’ |

| Difficulty obtaining information needed to complete tasks from insurance companies, labs, or employers | 38 | 20.1 | ‘Insurance companies having contradictory policy statements and I cannot speak with a human representative to help answer questions/ resolve the issue’ |

| Inadequate training, knowledge, or resources to complete tasks | 31 | 16.4 | ‘I did not receive formal training to address insurance/billing aspects and found it very difficult to "learn on the job" with little/no guidance or support’. |

| Unethical utilization of healthcare dollars | 6 | 3.2 | ‘Also, the high cost to insurance companies with small out-of-pocket for [patient] is ethically challenging for me…I do not like the “wink, wink” approach’ |

| Poor patient insurance literacy | 5 | 2.6 |

‘I find the underlying knowledge base of insurance and third-party payer systems is extremely lacking for most patients. It is difficult to explain the intricacies of insurance and genetic testing when there is a fundamental misunderstanding of how the system as a whole works’ ‘I sometimes feel so helpless when explaining [billing] to patients. They want everything to be “covered” or they call their insurance company before coming in and are told testing is “covered” then are enraged when they have a bill. I often spend time explaining the difference between “covered” and “paid for” as well as an [explanation of benefits] versus a bill’ |

| Institutional restrictions | 4 | 2.1 | ‘My institution only allows institutional billing so we cannot utilize the testing laboratory options for insurance investigation and decreased patient cost of testing’ |

| Total n = 189 | |||

4 DISCUSSION

Past studies have identified that insurance- and billing-related barriers are factors in patient decision-making regarding genetic testing and also present challenges to genetic counselor's workflow. This study further characterizes the current impacts of insurance and billing considerations on the genetic counseling practice in the United States. Specifically, we describe an inconsistent genesurance workflow among genetic counselors, a lack of consensus on who should be responsible for genesurance tasks, several challenges associated with completing these tasks, and identifies genesurance considerations as potential risk factors for genetic counselor burnout.

We found that most genetic counselors in this study experience a variety of challenges in incorporating insurance and billing considerations into their practice. Some aspects of workflow and attitudes were similar among the majority of respondents; however, many areas evaluated lacked consensus. Most importantly, respondents held different views as to whether insurance and billing tasks were even within the scope of genetic counseling practice. The absence of clear patterns among respondents makes it difficult to identify specific ways that the genetic counseling community can address these challenges.

We assessed the frequency and timing of several insurance- and billing-related tasks completed by patient-facing genetic counselors. How often tasks were completed was extremely variable, with a majority frequency being reached for only two tasks: answering patient questions daily and never giving exact out-of- pocket costs. The timing of tasks was less variable among respondents, but as previous studies have shown, these data indicated that many tasks are completed outside of direct patient counseling (Attard, Carmany, & Trepanier, 2018; Uhlmann et al., 2017). Tasks completed outside of genetic counseling sessions have the potential to take away from a genetic counselor's available time for direct patient care, a scenario that many respondents reported compromises the quality of patient care, as demonstrated by free responses categorized under time management issues (Table 2, Supplementary Table 1).

The informed consent process within a session can also be time-consuming due to insurance and billing factors. Respondents explained that because financial factors influence the decision to pursue testing for many patients, additional time is required within the session to explain the insurance process. However, the time it takes to provide financial informed consent is not the only challenge. It can also be difficult to determine the best point in time within a session to bring up the financial aspect of genetic testing to ensure patient understanding without overshadowing the clinical importance of a test. While Wagner et al. (2018) found that 79% of genetic counseling patients wished to discuss financial aspects of genetic testing before deciding whether or not to pursue testing, there are no professional guidelines for genetic counselors regarding when financial should be discussed with patients. The role of genesurance discussions in the informed consent process for genetic testing also remains unclear. This lack of guidance is reflected in the results of this study, with respondents initiating genesurance conversations at variable times throughout the genetic counseling session.

Time management is an increasing concern in the genetic counseling profession. Between 2016 and 2018, there was an average 30% increase in patient volume, with no significant changes in patient face-to-face time (National Society of Genetic Counselors, 2018a). A reported 67% of genetic counselors worked overtime hours each week, likely in an effort to maintain face-to-face time with an increasing patient population. It can be assumed that an increasing caseload also leads to an increase in time dedicated insurance and billing tasks both during and outside of sessions. Many of our respondents expressed feeling competent in insurance and billing tasks but described the main challenge as finding time with which to complete them.

The complexity of the current insurance and billing landscape in the United States exacerbates issues of time management as coverage varies among insurance plans and laboratories have varying billing policies which must be investigated for each individual patient. In addition, policies are frequently updated, sometimes without notice. The time and effort required to navigate these policies was frustrating for many respondents and may be partially attributed to the fact that a majority felt they lacked the resources and training to complete insurance and billing tasks. Surprisingly, having an institutional billing specialist as a resource did not appear to impact a genetic counselor's perception of challenges, with many citing that the billing specialist at their institution also lacked the appropriate training required to deal with insurance and billing for genetic testing.

Respondents indicated that inconsistency in policies not only complicates the processes required for insurance and billing, but also restricts the autonomy of laboratory and test selection. Results of this study show that insurance and billing considerations influence laboratory selection, and many of our participants stated that they were often unable to order the ideal test due to lack of insurance coverage, cost, or institutional contract restrictions (Table 2, Supplementary Table 1).

The fact that financial factors dictate the availability or type of testing for many patients leads to unequal access to care (Kutscher et al., 2017). For this reason, genetic counselors may view genesurance considerations as barriers to high-quality care, in that they may lead to circumstances in which genetic testing has been deemed appropriate, clinically important, and beneficial to the patient's overall care, but insurance or billing considerations make testing unattainable or undesirable for the patient. Currently, genetic counselors' influence on insurance reform for genetic testing is limited, especially because they are not currently recognized as providers by the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services. Addressing this issue is one of the 2019–2021 Strategic Goals of the NSGC, with two of the main objectives being the passage of the Access to Genetic Counselors Service Act and the engagement of third-party payers to streamline insurance and billing processes for genetic services (National Society of Genetic Counselors, 2018b).

One way to increase efficiency for any task is to ensure the proper training and resources are available, and despite most respondents reporting multiple learning settings and resources, a considerable number felt they lacked adequate training and access to resources. This disparity suggests the current resources available are not sufficient. Training adequacy is difficult to address due to the great variation in insurance and billing policies between states and institutions. Many respondents reported learning about insurance and billing through lectures and clinical experience in graduate school; however, specifics learned in their graduate training program were not applicable once they began working in another setting. Because graduate training programs cannot be expected to train students to be competent in every insurance and billing environment they will encounter in their career, these programs may not be the best modality for providing genetic counselors with the details of insurance and billing tasks. In addition, it may be a challenge to explicitly incorporate insurance and billing into the practice-based competencies published by the Accreditation Council for Genetic Counseling (Accreditation Council for Genetic Counseling, 2015). Currently, the competencies remain general, stating that genetic counseling students must be trained in ordering, investigating availability of, discussing costs of, and coordinating genetic testing. The primary challenge of explicitly addressing genesurance considerations in the ACGC competencies is that it remains unclear whether most, if any, insurance and billing are even within the scope of a genetic counselor. A second challenge would be addressing the nuances of insurance and billing tasks that can vary extensively between institutions; it would be challenging to ensure consistency among graduate training programs.

And while national and state-based professional societies have created training opportunities, they face the same inability to address institution-specific polices. Only 13.5% of respondents reported employer provided training. In addition, staffing issues may make employer provided training impossible at some institutions.

Creating helpful resources also poses challenges. While respondents were not asked which resources they felt were the most helpful, content from free responses suggests that insurance and billing challenges are alleviated in part by the publication of professional guidelines or recommendations. Many respondents found insurance and billing tasks easier to perform in the cancer setting and noted in their free responses that most insurance companies follow National Comprehensive Cancer Network guidelines for hereditary cancer testing coverage making reimbursement more uniform among payers. Some respondents practicing in the prenatal setting stated that recommendations by professional societies including the American College of Obstetrics and Gynecology as leading to consistent coverage of some prenatal genetic testing. However, it is clear that the creation of genetic testing guidelines, recommendations, or algorithms will never encompass every scenario encountered by genetics professionals, especially in the context of rare diseases, and would need frequent updating as genetic testing strategies evolve.

An additional challenge to creating a more uniform insurance and billing landscape for genetic testing is the fact that over a third of the genetic counselor respondents felt that insurance and billing considerations are outside the scope of genetic counseling, and over a quarter of respondents were unsure whether they are within the scope of the profession. This sentiment, along with the lack of agreement about who should be responsible for many insurance and billing tasks, illustrates why the challenges of insurance and billing considerations are so difficult to address for the genetic counseling community as a whole. Successful completion of the 2019–2021 NSGC Strategic Goal objective of making insurance and billing processes easier and less time-consuming will be welcomed by genetic counselors practicing in the United States, but will not address the issue that many genetic counselors may not believe that these processes should be the responsibility of genetic counselors.

The importance of addressing challenges associated with insurance and billing factors is clearly illustrated by the 85% of respondents who reported a negative impact on job satisfaction due to these factors. While most counselors in the 2018 Professional Status Survey reported overall job satisfaction (National Society of Genetic Counselors, 2018a), studies have shown that specific areas of dissatisfaction with the workplace can lead to clinician burnout. One study by Johnstone et al. (2016) found that burnout in genetic counselors was associated in part with increased patient volumes, increased workload, increased work hours, overextension of personal and workplace resources, time constraints, inadequate skills or training, and concerns for role boundaries. The current study has shown that most of the challenges of insurance and billing considerations fall within these burnout risks, suggesting insurance and billing tasks have a strong potential to contribute to genetic counselor burnout.

4.1 Practice implications

It will be difficult to determine ways that the genetic counseling community in the United States can address insurance and billing for genetic testing without first coming to a consensus on which, if any, insurance and billing tasks are within the scope and are the responsibility of a genetic counselor. Consensus toward either end is needed to guide how the issues must be addressed. Factors within the control of genetic counselor including workflow, training, and resources have the potential to impact in part how genetic counselors meet the challenges of insurance and billing, but problems caused by inconsistent coverage policies and billing will require changes by third-party payers and billing entities.

4.2 Study limitations

This study sampled only a subset of genetic counselors who directly counseled patients for at least 50% of their working hours and utilized a non-validated survey developed by the investigators. Those who had strong feelings regarding insurance and billing considerations may have been more likely to complete the survey leading to selection bias and polarized results. In addition, recall bias among respondents is possible, and when asked how genesurance impacts aspects of their role as a genetic counselor, the terms ‘job satisfaction’ and ‘patient interaction’ were not defined and may have been interpreted inconsistently by respondents. Another limitation is that prenatal genetic counselors were underrepresented in this study when compared to the 2018 NSGC Professional Status Survey demographic data. Finally, respondents working in multiple specialties were only given the opportunity to provide one generalized answer for each question, so data may not be fully representative for those respondents.

4.3 Research recommendations

Addressing the challenges found in this study will first require identification of which specific insurance and billing tasks, if any, genetic counselors believe are within the scope of practice. Future studies should focus on (a) investigating impacts between insurance and billing tasks and genetic counselor burnout and job satisfaction; (b) determining who the best person is for each insurance and billing task based on skill, training, and workflow efficiency; (c) characterizing, in more detail, the differences in insurance and billing considerations between specialties; and (d) engaging third-party payers to streamline insurance and billing processes for genetic services, as stated in the 2019–2021 NSGC Strategic Goals.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTION

All authors made substantial contributions to this study as outlined by the International Committee of Medical Journal Editors (ICMJE) and agreed to be accountable for all aspects of this work including the integrity of the data and accuracy of the data analysis. Emily Thoreson contributed to study design, survey development, data collection, data analysis, and manuscript drafting and editing. Chelsea Wagner contributed to study design, survey development, data collection, data analysis, and manuscript drafting and editing. Lauren Murphy contributed to study design, data analysis, and manuscript editing. Jennifer Lemons contributed to study design, survey development, data analysis, and manuscript editing. Laura Farach contributed to study design, survey development, data analysis, and manuscript editing. Kate Wilson contributed to study design, survey development, data analysis, and manuscript editing. Ashley Woodson contributed to study design, survey development, data analysis, and manuscript editing. Emily Thoreson and Chelsea Wagner have full access to all the data in this study and will ensure all questions related to the accuracy or integrity of this work are appropriately investigated and resolved.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This study was conducted while the first author (ET) was in training for fulfillment of a Master's degree in genetic counseling and was funded through a student research grant from the Texas Society of Genetic Counselors. The authors would like to acknowledge Dr. Syed S. Hashmi, MD, MPH, PhD for his contributions to statistical analysis and review of the manuscript.

COMPLIANCE WITH ETHICAL STANDARDS

Conflict of interest

The authors, Emily Thoreson, Chelsea Wagner, Lauren Murphy, Jennifer Lemons, Laura Farach, Kate Wilson, and Ashley Woodson declare that they have no conflicts of interest.

Human studies and informed consent

All procedures followed were in accordance with the ethical standards of the responsible committee on human experimentation (institutional and national) and with the Helsinki Declaration of 1975, as revised in 2000 (5). Informed consent was obtained from all participants for being included in the study.

Animal studies

No non-human animal studies were carried out by the authors for this article.

Open Research

DATA AVAILABILITY STATEMENT

The datasets generated during and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.