Genetic counselor and proxy patient perceptions of genetic counselor responses to prenatal patient self-disclosure requests: Skillfulness is in the eye of the beholder

Abstract

Research demonstrates some genetic counselors self-disclose while others do not when patients’ request self-disclosure. Limited psychotherapy research suggests skillfulness matters more than type of counselor response. This survey research assessed perceived skillfulness of genetic counselor self-disclosures and non-disclosures. Genetic counselors (n = 147) and proxy patients, women from the public (n = 201), read a hypothetical prenatal genetic counseling scenario and different counselor responses to the patient's question, What would you do if you were me? Participants were randomized either to a self-disclosure study (Study 1) or non-disclosure study (Study 2) and, respectively, rated the skillfulness of five personal disclosures and five professional disclosures or five decline to disclose and five redirecting non-disclosures. Counselor responses in both studies varied by intention (corrective, guiding, interpretive, literal, or reassuring). Participants also described what they thought made a response skillful. A three-way mixed ANOVA in both studies analyzed skillfulness ratings as a function of sample (proxy patient, genetic counselor), response type (personal, professional self-disclosure, or redirecting, declining non-disclosure), and response intention. Both studies found a significant three-way interaction and strong main effect for response intention. Responses rated highest in skillfulness by both genetic counselors and proxy patients in Study 1 were a guiding personal self-disclosure and a personal reassuring self-disclosure. The response rated highest in skillfulness by both samples in Study 2 was a redirecting non-disclosure with a reassuring intention. Proxy patients in both studies rated all literal responses as more skillful than genetic counselors. Participants’ commonly described a skillful response as offering guidance and/or reassurance. Counselor intentions and response type appear to influence perceptions, and counselors and patients may not always agree in their perceptions. Consistent with models of practice (e.g., Reciprocal-Engagement Model), genetic counselors generally should aim to convey support and guidance in their responses to prenatal patient self-disclosure requests.

1 INTRODUCTION

Genetic counselor self-disclosure is ‘…the genetic counselor's communication to the patient of information about her- or himself. Self-disclosure includes a range of information including demographics, beliefs, attitudes, perceptions, experiences, desires, and actions, as well as feelings about people and/or situations other than the patient…’ (McCarthy Veach, LeRoy, & Callanan, 2018, p. 303). Some research indicates genetic counseling patients often ask genetic counselors to self-disclose (Balcom, Veach, Bemmels, Redlinger-Grosse, & Leroy, 2013; Peters, McCarthy Veach, Ward, & LeRoy, 2004; Thomas, Veach, & LeRoy, 2006), and genetic counselors vary in how they respond, namely, some self-disclose while others do not (Redlinger-Grosse, Veach, & MacFarlane, 2013).

Limited psychotherapy research suggests skillfulness of a response is more important than response type (i.e. self-disclosure vs. non-disclosure) when clients ask their therapists to self-disclose (Hanson, 2005). To date, however, no studies have explicitly investigated the skillfulness of genetic counselor responses to patient self-disclosure requests. The present research assessed genetic counselor and proxy patient perceptions of the skillfulness of different self-disclosure and non-disclosure responses to a hypothetical prenatal patient's self-disclosure request.

1.1 Self-disclosure by healthcare providers

1.1.1 Psychotherapists

A number of psychotherapy studies indicate clinician self-disclosure can have both benefits and risks (Henretty, Currier, Berman, & Levitt, 2014; Henretty & Levitt, 2010). Studies further suggest a client's reactions to self-disclosure may depend on the skillfulness of the clinician's response and the strength of the therapeutic relationship (e.g., Hanson, 2005). Skillful self-disclosure is often brief, well timed, returns focus to the client, and is relevant to the session. Skillful self-disclosure may increase client trust, clinician likability and perceived competence, and strengthen the therapeutic relationship by providing clients with reassurance, support, and guidance, and by decreasing the power differential (Audet, 2011; Hanson, 2005; Waehler & Grandy, 2016). In contrast, unskillful self-disclosures can damage the therapeutic relationship by creating clinician–client role reversal, causing clients to feel judged, and lowering clients’ perceptions of the clinician's competence (Audet, 2011; Berg, Antonsen, & Binder, 2016; Hanson, 2005). Clients often view disclosures as unskillful when they are lengthy, mistimed, weaken therapist neutrality, remove focus from the client, seem irrelevant to the session, and are discordant with client values (Audet, 2011; Berg et al., 2016; Hanson, 2005).

One study found that skillful non-disclosures to patient requests were compassionate and included the clinician's reasons for refusing to self-disclose (Hanson, 2005). Hanson concluded that skillful non-disclosures may promote client understanding and acceptance of clinician non-disclosure and validate clients’ ability to make decisions. She further found that clients perceived unskillful non-disclosure responses as ‘rigid’.

1.1.2 Physicians

Research on physician self-disclosure suggests benefits and risks comparable to those obtained in psychotherapy research. Patients who receive helpful self-disclosure from physicians generally view it as positive, relationship building, and comforting, and they have enhanced perceptions of provider trustworthiness (Beach et al., 2004; Frank, Breyan, & Elon, 2000; Zink et al., 2017). Physicians view self-disclosure as a beneficial way to express empathy and understanding, provide motivation, suggest new therapies, and give patients hope (Allen & Arroll, 2015). Risks of physician self-disclosure include the possibility of blurring professional boundaries between patient and provider and hindering relationship building when used unskillfully (Allen & Arroll, 2015; Gabbard & Nadelson, 1995; Zink et al., 2017). Similar to findings in psychotherapy studies, unskillful physician self-disclosures are tangential to the patient or the context of the visit, lack patient focus (McDaniel et al., 2007), and/or verbosely describe personal experiences with little apparent relevance for the patient (Beach et al., 2004).

1.1.3 Genetic counselors

Postulated benefits of counselor self-disclosure in the genetic counseling literature include enhancing the counselor–patient relationship by increasing trust and rapport (cf. Weil, 2000). Research on effects of genetic counselor self-disclosure suggest self-disclosure can improve the therapeutic relationship, increase genetic counselor likability, and increase patient satisfaction (Paine et al., 2010; Volz, Valverde, & Robbins, 2018). Hypothesized risks include removing the focus from the patient and triggering harmful countertransference in the genetic counselor (cf. Kessler, 1992).

Research suggests that patients’ motivations for requesting self-disclosure include seeking guidance, looking for validation, respecting the genetic counselor's opinion, and building the counselor–patient relationship (Thomas et al., 2006). Balcom et al. (2013) interviewed prenatal genetic counselors and found the most frequently requested type of self-disclosure concerned the patient question, ‘What would you do in my situation?’ The researchers identified four types of genetic counselor responses to patients’ requests for self-disclosure: personal disclosure (e.g. ‘I would do…’), professional disclosure (e.g. ‘Some patients…’), redirecting non-disclosure (e.g. ‘Let's focus on what's most important for you’), and decline to disclose (e.g. ‘Circumstances are different’).

Balcom et al.’s (2013) participants perceived self-disclosure responses as successful when they were brief and returned focus to the patient, and they perceived non-disclosures as successful when they contained the counselor's reason(s) for not disclosing. They perceived non-disclosures as unsuccessful when they lacked an explanation for the response, and this either provoked patient frustration or damaged the counseling relationship. Their perceptions of skillful self-disclosures and non-disclosures align with findings from Hanson’s (2005) study of psychotherapy clients.

Redlinger-Grosse et al. (2013) surveyed genetic counselors and genetic counseling students and found their responses varied for two hypothetical scenarios in which a prenatal patient requested self-disclosure. The patient asked, ‘What would you do?’ in one scenario, and in the other, ‘Have you ever had an amniocentesis?’ In each scenario, participants responded in writing to the patient. Then they provided the researchers with a reason for their response.

Across both participant groups, responses included professional self-disclosure, personal self-disclosure, a mixture of personal and professional self-disclosure, and non-disclosures that were either redirecting or declining to disclose. Counselor reasons for self-disclosure were as follows: to remain patient focused, build the relationship, promote decision-making, support or empower the patient, and being comfortable with the patient's question. Non-disclosing counselors’ reasons were as follows: to remain patient focused, remain non-directive, support or empower the patient, maintain privacy, and viewing self-disclosure as irrelevant. The researchers coded the implied emphasis of the written responses, extracting five categories: interpretive, literal, corrective, guiding, and reassuring. These categories were evident across all types of counselor responses (i.e., personal disclosure, professional disclosure, redirecting, and declining to disclose).

1.2 Purpose of the study

The genetic counseling studies reviewed herein show that genetic counselors vary in their responses to patients’ self-disclosure requests. To date, however, no research has investigated the skillfulness of their responses. Research on psychotherapist (Hanson, 2005) and physician self-disclosure (McDaniel et al., 2007) suggests skillfulness may moderate the effects of clinician self-disclosure and non-disclosure responses. As studies of response skillfulness may contribute to genetic counselor training, supervision, and practice, the present study assessed genetic counselor and proxy patients’ perceptions of the skillfulness of genetic counselor responses to a hypothetical prenatal patient's self-disclosure request. Counselor responses encompass Redlinger-Grosse et al.’s (2013) professional self-disclosure, personal self-disclosure, redirecting non-disclosure, and decline non-disclosure responses and their five response intentions (interpretive, literal, corrective, guiding, and reassuring). To limit survey fatigue and because the types of counselor responses were not the same between self-disclosure (i.e., personal vs. professional) and non-disclosure (i.e., redirecting vs. decline), participants were only shown either self-disclosure responses or non-disclosure responses. The data were therefore analyzed as two separate studies.

The major research questions were identical for both studies: (a) Which types of responses do genetic counselors perceive as most skillful? (b) Which type(s) of responses do proxy patients perceive as most skillful? (c) Are there between group differences in genetic counselor and proxy patient perceptions of response skillfulness?

2 OVERALL PARTICIPANT RECRUITMENT

2.1 Participants

The populations of interest for this mixed methods survey research were practicing genetic counselors and prenatal genetic counseling patients. Given the logistical difficulties associated with recruiting a large sample of actual prenatal patients, we recruited women from the public as proxy patients. Arguably, they might be or have been prenatal patients during their lives. Upon approval from the University of Minnesota Institutional Review Board, we recruited two participant samples: genetic counselors enrolled in the National Society of Genetic Counselors (NSGC) listserv and Amazon's Mechanical Turk (MTurk) workers. Participants were recruited in one wave and randomized to either Study 1 or Study 2.

2.1.1 Genetic counselor sample

Inclusion criteria for the genetic counselor sample were current practice in a clinical or non-clinical setting in North America, and being certified by the American Board of Genetic Counselors (ABGC) or board eligible. A research invitation containing an anonymous link to the survey was sent to individuals enrolled in the NSGC listserv (~n = 3,431). The invitation described the study's purpose as furthering information about genetic counselor responses to patient requests for self-disclosure, and it contained the inclusion criteria. The initial invitation, sent in October 2017, with a reminder email sent 2 weeks later, yielded 169 returned surveys. Of these, 18 respondents discontinued the survey after completing one section, and four discontinued the survey after completing two sections. Thus, the final sample of genetic counselors was 147.

2.1.2 Proxy patient sample

Proxy patient participants were recruited through Amazon's MTurk marketplace using a study description and link to an anonymous survey. Inclusion criteria were being women, over the age of 18 years, and residing in the United States. These criteria were used to increase similarities between participants and the hypothetical prenatal patient.

MTurk is an online marketplace hosted by Amazon where requesters can upload tasks, including surveys, and MTurk workers can complete these tasks for monetary reward. Individuals are only able to access tasks when their demographic information meets participation criteria. Research has shown no significant association between pay rate and data quality and internal consistency (Litman, Robinson, & Rosenzweig, 2015). Researchers comparing MTurk workers to traditional research pools have found that MTurk workers perform similarly to undergraduate and community research pools (Goodman, Cryder, & Cheema, 2013; Paolacci, Chandler, & Ipeirotis, 2010). In addition to being a reliable source of data, MTurk workers tend to be more diverse participants than those recruited in an academic setting (Behrend, Sharek, Meade, & Wiebe, 2011; Casler, Bickel, & Hackett, 2013).

The study description informed potential MTurk participants that the survey consisted of one page of background information, a genetic counseling scenario, skillfulness rating questions, and demographic questions. The survey was available in September 7, 2017 and reached the maximum number of desired participants (n = 200) that same day. A unique tracker ensured participants could only complete the patient survey once (Paolacci et al., 2010). Each respondent received $0.40 upon survey completion. One MTurk worker completed the survey but did not complete payment submission. The survey was closed after receipt of surveys from 201 eligible respondents. De-identified information was collected from each respondent and cross-referenced to ensure there were no duplicate survey submissions. The final proxy patient sample was 201.

Participants were then randomized into either Study 1 (n = 175) or Study 2 (n = 193). Demographics for genetic counselors across the whole sample, and for each study, are presented in Table 1. The majority were women (97.3%), Caucasian or white (95.2%), and married or in a committed relationship (71%). These demographics are comparable to those of respondents to a recent NSGC Professional Status Survey (PSS; NSGC, 2019). They had an average of 6.5 years of genetic counseling experience, 98% had seen patients within the past 5 years, and they varied in their practice specialties and work settings. Genetic counselors were more likely to work in a university medical center, public hospital, or private hospital (71%) compared to PSS respondents (62%). About 28% reported prenatal genetic counseling as a practice specialty, which is comparable to PSS respondents (29%). When asked about their disclosure behaviors, only about 5% of genetic counselors said they were likely or very likely to disclose personal opinions, and 17% said they were likely or very likely to disclose personal experiences. In contrast, about 92% of the genetic counselors indicated they were likely or very likely to disclose professional experiences. Randomization did not produce any statistically significant differences in demographics between those placed in Study 1 versus Study 2.

| Variable | Totala | Study 1b (disclosure) | Study 2c (non-disclosure) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n | % | n | % | n | % | |

| Age (years) | ||||||

| Mean | 32.6 | — | 32.2 | — | 33.0 | — |

| Range | 24–67 | — | 24–59 | — | 24–67 | — |

| Years of genetic counseling experience | ||||||

| Mean | 6.5 | — | 6.5 | — | 6.6 | — |

| Range | 1–35 | — | 1–35 | — | 1–33 | — |

| Gender | ||||||

| Female | 142 | 97.3 | 68 | 98.6 | 74 | 96.1 |

| Male | 4 | 2.7 | 1 | 1.4 | 3 | 3.9 |

| Ethnic background | ||||||

| Caucasian or White | 139 | 95.2 | 65 | 94.2 | 74 | 96.1 |

| Asian | 2 | 1.4 | 1 | 1.4 | 1 | 1.3 |

| Bi-racial | 1 | 0.7 | 1 | 1.4 | 0 | 0.0 |

| Hispanic/Chicano/Latina(o) | 1 | 0.7 | 1 | 1.4 | 0 | 0.0 |

| Other | 3 | 2.1 | 1 | 1.4 | 2 | 2.6 |

| Relationship status | ||||||

| Legally married | 74 | 51.0 | 36 | 45.6 | 38 | 50.0 |

| Single | 38 | 26.2 | 19 | 24.1 | 19 | 25.0 |

| CLTR/partnered | 29 | 20.0 | 12 | 15.2 | 17 | 22.4 |

| Divorced | 3 | 2.1 | 1 | 1.4 | 2 | 2.6 |

| Other | 1 | 0.7 | 1 | 1.4 | 0 | 0.0 |

| Likelihood of disclosing personal opinions | ||||||

| Very unlikely | 64 | 43.5 | 26 | 37.7 | 38 | 48.7 |

| Unlikely | 76 | 51.7 | 42 | 60.9 | 34 | 43.6 |

| Likely | 7 | 4.8 | 1 | 1.4 | 6 | 7.7 |

| Very likely | 0 | 0.0 | 0 | 0.0 | 0 | 0.0 |

| Likelihood of disclosing personal experiences | ||||||

| Very unlikely | 33 | 22.5 | 17 | 24.6 | 16 | 20.5 |

| Unlikely | 89 | 60.5 | 39 | 56.5 | 50 | 64.1 |

| Likely | 24 | 16.3 | 12 | 17.4 | 12 | 15.4 |

| Very likely | 1 | 0.7 | 1 | 1.4 | 0 | 0.0 |

| Likelihood of disclosing professional experiences | ||||||

| Very unlikely | 0 | 0.0 | 0 | 0.0 | 0 | 0.0 |

| Unlikely | 12 | 8.2 | 10 | 14.5 | 2 | 2.6 |

| Likely | 97 | 66.0 | 44 | 63.8 | 53 | 67.9 |

| Very likely | 38 | 25.9 | 15 | 21.7 | 23 | 29.5 |

| NSGC Region | ||||||

| Region I | 8 | 5.5 | 4 | 5.9 | 4 | 5.2 |

| Region II | 34 | 23.5 | 14 | 20.6 | 20 | 26.0 |

| Region III | 20 | 13.8 | 12 | 17.6 | 8 | 10.4 |

| Region IV | 39 | 26.9 | 15 | 22.1 | 24 | 31.2 |

| Region V | 18 | 12.4 | 9 | 13.2 | 9 | 11.7 |

| Region VI | 23 | 15.9 | 13 | 19.1 | 10 | 13.0 |

| Clinically seen patients in the past 5 years | ||||||

| Yes | 143 | 98.0 | 68 | 98.6 | 75 | 97.4 |

| No | 3 | 2.1 | 1 | 1.3 | 2 | 2.6 |

| n | % | n | % | n | % | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Work specialtyd | ||||||

| Prenatal | 64 | 43.5 | 30 | 43.5 | 34 | 44.2 |

| Cancer | 53 | 36.1 | 24 | 30.4 | 29 | 52.7 |

| Pediatric | 28 | 19.0 | 12 | 17.4 | 16 | 20.8 |

| General genetics | 24 | 16.3 | 8 | 11.6 | 16 | 20.8 |

| Genetic testing | 17 | 11.6 | 6 | 8.7 | 11 | 14.3 |

| Specialty disease | 9 | 6.1 | 5 | 7.2 | 4 | 5.2 |

| PG/preconception | 8 | 5.4 | 4 | 5.1 | 4 | 5.2 |

| Cardiology | 7 | 4.8 | 4 | 5.8 | 3 | 3.9 |

| Neurogenetics | 7 | 4.8 | 2 | 2.9 | 5 | 5.7 |

| Metabolic disease | 2 | 1.3 | 1 | 1.4 | 1 | 1.3 |

| Other | 6 | 4.1 | 4 | 5.1 | 2 | 2.6 |

| Primary work setting | ||||||

| University medical center | 59 | 40.7 | 29 | 42.0 | 30 | 39.5 |

| Private hospital or facility | 44 | 30.3 | 21 | 30.4 | 23 | 30.3 |

| Diagnostic laboratory | 10 | 6.9 | 4 | 5.8 | 6 | 7.9 |

| Group private practice | 10 | 6.9 | 6 | 7.6 | 4 | 5.3 |

| Federal, state, county office | 2 | 1.4 | 0 | 0.0 | 2 | 2.3 |

| Health maintenance Organization | 1 | 0.7 | 0 | 0.0 | 1 | 1.1 |

| Individual private practice | 1 | 0.7 | 0 | 0.0 | 1 | 1.1 |

| Other | 18 | 12.4 | 9 | 11.4 | 9 | 11.8 |

- Abbreviation: CLTR, Committed, long-term relationship.

- a n = 147.

- b n = 69.

- c n = 78.

- d Participants could endorse multiple specialties.

Demographics for the proxy patients across the whole sample, and for each study, are presented in Table 2. The majority self-identified as Caucasian or white (72.8%), were married or in a committed relationship (74%), and had a college degree or higher (55.5%). Sixty-eight percent reported having heard the term genetic counseling prior to this study, although only 28% indicated they were familiar or very familiar with it. Randomization did not produce any statistically significant differences in demographics between those placed in Study 1 versus Study 2.

| Variable | Totala | Study 1b (disclosure) | Study 2c (non-disclosure) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n | % | n | % | n | % | |

| Age (years) | ||||||

| Mean | 36.9 | — | 35.8 | — | 37.8 | — |

| Range | 19–71 | — | 19–70 | — | 20–71 | — |

| Ethnic Background | ||||||

| Caucasian or White | 147 | 72.8 | 71 | 74.0 | 76 | 72.4 |

| Asian | 23 | 11.4 | 10 | 10.4 | 13 | 12.4 |

| Black or African American | 12 | 5.9 | 4 | 5.2 | 7 | 6.7 |

| Hispanic/Chicano/Latina(o) | 9 | 4.5 | 4 | 4.2 | 5 | 4.8 |

| American Indian or Alaskan Native | 3 | 1.5 | 1 | 1.0 | 2 | 1.9 |

| Bi-racial | 3 | 1.5 | 2 | 2.1 | 1 | 1.0 |

| Other | 4 | 2.0 | 3 | 3.1 | 1 | 1.0 |

| Relationship Status | ||||||

| Legally married | 108 | 53.7 | 52 | 54.2 | 56 | 53.3 |

| CLTR/Partnered | 41 | 20.3 | 20 | 20.8 | 21 | 20.0 |

| Single | 36 | 17.8 | 16 | 16.7 | 20 | 19.0 |

| Divorced | 13 | 6.4 | 8 | 8.3 | 5 | 4.8 |

| Widowed | 3 | 1.5 | 0 | 0.0 | 3 | 2.9 |

| Highest level of education | ||||||

| Some high school | 2 | 1.0 | 1 | 1.0 | 1 | 1.0 |

| High School Graduate/GED | 20 | 9.9 | 8 | 8.3 | 12 | 11.4 |

| Some college, no degree | 41 | 20.3 | 21 | 21.9 | 20 | 19.0 |

| Associate's degree | 26 | 12.9 | 14 | 14.6 | 12 | 11.4 |

| Bachelor's degree | 76 | 37.6 | 33 | 34.3 | 43 | 41.0 |

| Master's degree | 27 | 13.4 | 13 | 13.5 | 14 | 13.3 |

| Doctorate/professional degree | 9 | 4.5 | 6 | 6.2 | 3 | 2.9 |

| Do you have children | ||||||

| Yes | 111 | 58.4 | 48 | 53.9 | 63 | 62.4 |

| No | 79 | 41.4 | 41 | 46.1 | 38 | 36.2 |

| Heard of genetic counseling | ||||||

| Yes | 137 | 68.0 | 69 | 71.9 | 68 | 64.8 |

| No | 54 | 27.2 | 24 | 25.0 | 30 | 28.6 |

| Not sure | 10 | 4.9 | 3 | 3.1 | 7 | 6.7 |

| Familiarity with genetic counseling | ||||||

| Little/no familiarity | 65 | 32.3 | 34 | 35.4 | 31 | 29.5 |

| Somewhat familiar | 79 | 39.3 | 39 | 40.6 | 40 | 38.1 |

| Familiar | 36 | 17.5 | 13 | 13.5 | 23 | 21.9 |

| Very familiar | 21 | 10.5 | 10 | 10.4 | 11 | 10.5 |

| Offered genetic testing | ||||||

| Yes | 69 | 34.3 | 36 | 37.5 | 33 | 31.4 |

| No | 131 | 65.2 | 60 | 62.5 | 71 | 67.6 |

| Not sure | 1 | 0.5 | 0 | 0.0 | 1 | 1.0 |

| Had genetic testing | ||||||

| Yes | 41 | 40.0 | 24 | 25.0 | 17 | 16.2 |

| No | 160 | 60.0 | 72 | 75.0 | 88 | 83.8 |

- Abbreviation: CLTR = Committed, long-term relationship.

- a n = 201.

- b n = 96.

- c n = 105.

3 STUDY 1: SELF-DISCLOSURE RESPONSES

3.1 Methods

3.1.1 Instrumentation and procedures

Stimulus materials comprised parallel forms of a survey developed based on a hypothetical prenatal genetic counseling scenario and genetic counselors’ written responses to a scenario from Redlinger-Grosse et al. (2013). The first section of each survey contained the scenario in which a patient (Katie) is referred for genetic counseling and amniocentesis at 16 weeks gestation for the indication of advanced maternal age. At the end of the session, Katie expresses some hesitation about the amniocentesis and asks the genetic counselor, ‘What would you do if you were me?’ On the genetic counselor version of the survey, participants were asked to imagine they were the counselor in the scenario. On the proxy patient version of the survey, participants were asked to imagine they were the patient in the scenario.

The proxy patient survey began with a definition of genetic counseling adapted from the NSGC scope of practice (National Society of Genetic Counselors, n.d.): ‘Genetic counseling is the process of providing information and support to families who may be at risk for a variety of genetic or inherited conditions’. A brief description of prenatal genetic counseling followed the definition, including why Katie would see a prenatal genetic counselor at age 35; a description of Trisomy 13, Trisomy 18 and Trisomy 21; and a description of amniocentesis and associated risk for miscarriage. The hypothetical scenario followed this information.

A series of counselor responses to Katie's question (‘What would you do if you were me?’) followed the scenario on both the genetic counselor and proxy patient forms of the survey. Participants viewed five different professional self-disclosure responses and five different personal self-disclosure responses. The order of viewing professional or personal responses first was randomized, as was the order of the responses on each page, thus limiting potential order effects.

Each counselor response on a page had either an interpretive, reassuring, corrective, guiding, or a literal intention. As defined by Redlinger-Grosse et al. (2013), ‘[an interpretive response] provided insight into the possible reason for the patient's question; literal response-the response addressed the surface content of the patient's request by providing information; corrective response-the response reminded the patient she was in a different situation than the counselor; guiding response-the response attempted to facilitate the decision making for the patient; reassuring response-the response offered support to the patient’ (p. 464). Table 3 contains the counselor self-disclosure responses used in the present study. They are amalgamations of the most prevalent genetic counselor responses obtained by Redlinger-Grosse et al. (2013).

| Interpretive | Reassuring | Corrective | Guiding | Literal | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Professional Self-Disclosure | ‘In my experience, some women are concerned about the risk of an amniocentesis and what an abnormal result means to them. Is this something you're concerned about?’ | ‘I get asked this a lot by patients. Many of my patients are uncertain of what they want to do. I don't think there's a wrong choice, but there is a best choice for you’ | ‘A lot of people have asked me that, but what I would do doesn't matter. I see women in your position every day, and they all make their decision for different reasons’ | ‘Other patients I’ve seen in this situation often think about their families, their values, and what they would do with the results from the amniocentesis’ | ‘Other patients that I have seen in this situation have chosen to proceed with the amniocentesis, too’ |

| Personal Self-Disclosure | ‘I don't know what I would do. It is a lot to think about. But, you said that you came here with good reasons for having the amniocentesis. Has that changed?’ | ‘I would do exactly what you're doing and think about all the reasons to have an amniocentesis, and all the reasons to not have an amniocentesis. It's very normal to have these conflicting thoughts’ | ‘In all honesty Katie, I'm not sure what I would do. I’m not you and I can't truly know what you are feeling right now’ | ‘I'm not trying to avoid your question, but many factors go into this decision. If I were you, I’d consider how much I wanted to know if there's a chromosome problem versus the risks of the procedure. Then I’d decide what would make me the most comfortable during the pregnancy’ | ‘I’m not sure. However, based on everything you have told me today, if I were you, I would move forward with the amniocentesis’ |

| Non-Disclosure Redirecting | ‘Perhaps you're asking what I would do because you're feeling unsure about wanting an amniocentesis?’ | ‘This is a tough decision. Let's talk about the issues you're thinking about, so you can make the choice that is best for you and your family’ | ‘That answer depends on many things. It's really a personal decision Let's focus on what's most important to you’ | ‘Well, there are a number of factors that go into a decision like this. Why don't we re-visit your options now and talk through what each scenario may bring’ | ‘Well, let's go over some of the options again’ |

| Non-Disclosure Decline to Disclose | ‘It's a very personal decision, and I can't say what I would do. Perhaps the information we discussed has you questioning your original plan?’ | ‘I really cannot answer that. But we can talk through the different options so you can reach a decision that's best for you’ | ‘I’m not you and this is a very personal decision. Only you can answer that question. What I would do might not necessarily be what is best for you’ | ‘I really can't answer that. I want to help you weigh your priorities and concerns and find the right decision for you. Let's think about what's important to you’ | ‘This is a difficult question. I can't say what I would do’ |

Participants rated each counselor response using a 6-point Likert scale (1 = Unskillful, to 6 = Skillful). To avoid biasing responses, the survey did not contain a definition of ‘skillful’. After rating the five counselor responses on the first page, participants were asked to describe what they thought made a response skillful. Participants repeated this process for the five counselor responses on the second page.

A final section of the genetic counselor survey included demographic questions (age, gender, ethnic background, relationship status, years of experience, specialty, primary work setting, NSGC region of practice, board certification, and if they have seen a patient clinically within the past 5 years). Three questions asked how likely they were to disclose personal opinions, personal experiences, and professional experiences to patients (Scale: 1 = Very Unlikely, to 4 = Very Likely).

A final section of the proxy patient survey contained demographic questions (age, gender, ethnic background, relationship status, whether they have children, highest level of education, zip code, household income, and household size). There were also questions asking whether participants had heard the term ‘genetic counseling’ prior to the survey (yes/no/not sure), and if so, how they heard about it; their familiarity with genetic counseling (Scale: 1 = Little/No Familiarity, to 4 = Very Familiar); and whether they had ever been offered or completed a genetic test (yes/no/not sure).

After several iterations, the counselor and patient surveys were piloted on one experienced genetic counselor and one female MTurk worker. Their feedback resulted in minor formatting modifications to improve clarity of the scenario on both surveys, and the background information on the patient survey.

3.1.2 Data analysis

Quantitative data

Descriptive statistics were calculated for responses to survey items, including marginal means, standard errors, frequencies, and ns. Due to randomization, the number of participants in each study varied. The research is a 2 × 2 × 5 mixed design. A three-way mixed analysis of variance (ANOVA) assessed main and interaction effects of participant sample (genetic counselors; proxy patients), type of self-disclosure (personal vs. professional), and response intention (interpretive, reassuring, corrective, guiding, or literal) on participants’ Likert ratings of counselor response skillfulness.

Qualitative data

The first and second authors independently analyzed responses to open-ended items asking participants to describe what made a response skillful. They used an a priori framework based on Redlinger-Grosse et al.’s (2013) five categories of genetic counselor response intentions: interpretive, reassuring, corrective, guiding, and literal. They also used thematic analysis (Silverman, 1993), an inductive approach, to extract additional categories for responses that could not otherwise be classified within the a priori categories. The senior author audited their categorizations. The coders and auditor used discussion to obtain concordance regarding final classifications.

4 RESULTS

4.1 Skillfulness ratings of the genetic counselor self-disclosure responses

4.1.1 Descriptive analyses

Table 4 contains the means and standard errors for skillfulness ratings of each genetic counselor self-disclosure response. On a 6-point scale (1 = Unskillful, 6 = Skillful), means for the 10 self-disclosure responses ranged from 1.42 to 4.59 for the genetic counselor sample, and from 2.85 to 4.68 for the proxy patient sample. For six of the 10 self-disclosure responses, genetic counselor and proxy patient mean ratings were above 3.50, suggesting they, on average, perceived these responses as more skillful, rather than less skillful.

|

Interpretive M (SE) |

Literal M (SE) |

Corrective M (SE) |

Guiding M (SE) |

Reassuring M (SE) |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Professional SD | |||||

| Proxy Pt | 4.52 (0.13) | 2.85 (0.12) | 3.37 (0.15) | 3.76 (0.14) | 4.33 (0.13) |

| GC | 3.84 (0.17) | 1.42 (0.15) | 2.67 (0.17) | 4.25 (0.17) | 4.07 (0.16) |

| Personal SD | |||||

| Proxy Pt | 3.93 (0.15) | 3.40 (0.12) | 2.87 (0.14) | 4.67 (0.13) | 4.68 (0.12) |

| GC | 4.22 (0.17) | 1.59 (0.15) | 2.30 (0.17) | 4.59 (0.15) | 4.45 (0.14) |

Note

- Ratings are based on a 6-point scale where 1 = unskillful and 6 = skillful; SD = self-disclosure; Pt = patient; GC = genetic counselor.

The self-disclosure responses with the highest mean ratings in both samples were personal self-disclosure with a guiding intention (I'm not trying to avoid your question, but many factors go into this decision. If I were you, I’d consider how much I wanted to know if there's a chromosome problem vs. the risks of the procedure. Then I’d decide what would make me the most comfortable during the pregnancy), and personal self-disclosure with a reassuring intention (I would do exactly what you're doing and think about all the reasons to have an amniocentesis, and all the reasons to not have an amniocentesis. It's very normal to have these conflicting thoughts). The self-disclosure response with the lowest mean ratings in both samples was professional self-disclosure with a literal intention (Other patients that I have seen in this situation have chosen to proceed with the amniocentesis, too).

4.1.2 Inferential analyses

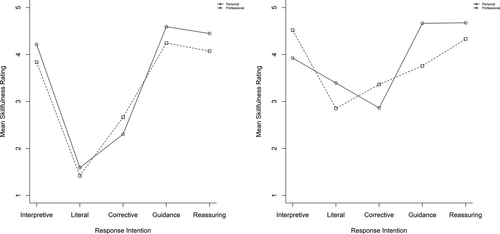

A three-way mixed ANOVA assessed differences in skillfulness ratings for counselor self-disclosure responses as a function of sample (proxy patient, genetic counselor), response type (personal, professional), and response intentions (interpretive, literal, corrective, guiding, reassuring). The ANOVA yielded a significant three-way interaction [F(4,652) = 5.49, p < .001,  = 0.03], as well as a very strong main effect for response intention [F(4,652) = 168.87, p < .001,

= 0.03], as well as a very strong main effect for response intention [F(4,652) = 168.87, p < .001,  = 0.51]. Full ANOVA results are presented in the Supplemental materials (see Table S1). The three-way interaction is presented in Figure 1.

= 0.51]. Full ANOVA results are presented in the Supplemental materials (see Table S1). The three-way interaction is presented in Figure 1.

The pattern of skillfulness ratings was different for genetic counselors and proxy patients. Genetic counselors had virtually identical patterns of skillfulness ratings for both the personal and professional disclosure response types, with interpretive, guiding, and reassuring intention statements being rated as substantially more skillful than the literal and corrective intention statements. The proxy patients similarly tended to view interpretive and reassuring intention statements as more skillful than literal and corrective intention statements, but the gap between them was much smaller than for the genetic counselors. The proxy patients also found the guiding intention statement to be more skillful in the personal self-disclosure than in the professional self-disclosure.

While main effects are typically not interpreted in the presence of significant interactions, they can still provide useful information in some cases. Given the interaction is primarily ordinal and the very large effect size of the main effect of response intention ( = 0.51) in both an absolute sense and relative to the effect size of the interaction (

= 0.51) in both an absolute sense and relative to the effect size of the interaction ( = 0.03), exploration of the post hoc tests for response intention is justified. Full results of the post hoc analyses are available in Table S2. There were no significant differences between the interpretive, guiding, or reassuring response intention skillfulness ratings (p range: .06–.96), and all three of these intentions were rated as more skillful than corrective or literal (p range: <.001–.002). Corrective response intentions were also rated as more skillful than literal intentions (p<.001).

= 0.03), exploration of the post hoc tests for response intention is justified. Full results of the post hoc analyses are available in Table S2. There were no significant differences between the interpretive, guiding, or reassuring response intention skillfulness ratings (p range: .06–.96), and all three of these intentions were rated as more skillful than corrective or literal (p range: <.001–.002). Corrective response intentions were also rated as more skillful than literal intentions (p<.001).

5 DISCUSSION OF STUDY 1 SKILLFULNESS RATINGS

The most highly rated personal self-disclosure responses by both genetic counselors and proxy patients were guiding and reassuring self-disclosure. The professional self-disclosure with the highest rating by genetic counselors was guiding while proxy patients rated the interpretative intention highest. Genetic counselors as a group viewed all disclosures with guiding, or reassuring, or interpretive intentions as significantly more skillful than corrective or literal responses. Proxy patients tended to view interpretive and reassuring self-disclosures as more skillful than those with corrective or literal intentions, although the differences were small, and they found a guiding intention to be more skillful for the personal self-disclosure statement than for the professional self-disclosure statement.

The generally favorable ratings for self-disclosure responses with guiding, reassuring, or interpretive intentions are consistent with the goals of the Reciprocal Engagement Model (REM; McCarthy Veach, Bartels, & LeRoy, 2007) of genetic counseling practice. A guiding intention aligns with the goal of facilitating collaborative decisions with patients. This intention is also congruent with findings that genetic counseling patients expect guidance from genetic counseling sessions (Davey, Rostant, Harrop, Goldblatt, & O’Leary, 2005; Michie, Marteau, & Bobrow, 1997), and with genetic counselors’ perceptions that some patients request self-disclosure because they desire guidance (Balcom et al., 2013; Thomas et al., 2006).

Reassuring responses align with the REM goal of facilitating the patient's feelings of empowerment and the REM tenet that patient feelings matter (McCarthy Veach et al., 2007). Patient reassurance/validation is also a proposed genetic counseling outcome (Redlinger-Grosse et al., 2016). The present findings are also consistent with research indicating genetic counseling patients expect reassurance or emotional support from genetic counseling appointments (Michie et al., 1997), and with genetic counselor beliefs that some patients request self-disclosure because they want validation (Balcom et al., 2013; Thomas et al., 2006). Interpretive responses correspond to two REM goals, namely, recognizing concerns that are triggering the patient's emotions, and helping patients gain new perspectives (McCarthy Veach et al., 2007).

Both genetic counselors and proxy patients rated the corrective professional self-disclosure response as unskillful; and genetic counselors also rated the corrective personal self-disclosure response as unskillful. Corrective responses contradict the patient, and thus may be perceived as contrary to a genetic counseling goal of providing patient support.

A large majority of genetic counselors and proxy patients perceived literal self-disclosures to be least skillful. Furthermore, the proxy patients rated the literal personal self-disclosure statement as more skillful than the literal professional self-disclosure statement. The mean ratings were below 3.5, however, suggesting they perceived both responses as less, rather than more, skillful.

6 STUDY 2: NON-DISCLOSURE RESPONSES

6.1 Methods

6.1.1 Instrumentation and procedures

The stimulus materials were identical to Study 1 with the exception of the types of disclosures presented to participants. In this study, the participants viewed five different redirecting non-disclosure responses and five different declining non-disclosure responses to a patient request for self-disclosure. The order of viewing redirecting or declining responses first was randomized, as was the order of the responses on each page, thus limiting potential order effects. Each counselor response on a page had either an interpretive, reassuring, corrective, guiding, or a literal intention based on amalgamations of the most prevalent genetic counselor responses obtained by Redlinger-Grosse et al. (2013). Table 3 contains the non-disclosure responses used in Study 2.

Identical to Study 1, after several iterations, the counselor and patient surveys were piloted on one experienced genetic counselor and one female MTurk worker. Their feedback resulted in minor formatting modifications to improve clarity of the scenario on both surveys, and the background information on the patient survey.

6.1.2 Data analysis

The data analyses were identical to Study 1 for both the quantitative and qualitative data, with the exception of the second IV in the ANOVA, which is now type of non-disclosure (redirect vs. decline).

7 RESULTS

7.1 Skillfulness ratings of the genetic counselor non-disclosure responses

7.1.1 Descriptive analyses

Table 5 contains the means and standard errors for ratings of the skillfulness of each genetic counselor non-disclosure response. Means for the 10 non-disclosure responses ranged from 1.79 to 4.99 for the genetic counselor sample, and from 2.10 to 4.98 for the proxy patient sample. Genetic counselors’ and proxy patients’ mean ratings for 6 of the 10 non-disclosure responses were above 3.50, suggesting they, on average, perceived these responses as more, rather than less, skillful.

|

Interpretive M (SE) |

Literal M (SE) |

Corrective M (SE) |

Guiding M (SE) |

Reassuring M (SE) |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Decline ND | |||||

| Proxy Pt | 3.35 (0.12) | 2.10 (0.12) | 3.08 (0.14) | 4.22 (0.14) | 4.15 (0.13) |

| GC | 4.00 (0.15) | 1.79 (0.14) | 3.31 (0.16) | 3.96 (0.16) | 3.07 (0.15) |

| Redirect ND | |||||

| Proxy Pt | 3.20 (0.14) | 4.03 (0.12) | 4.51 (0.14) | 4.96 (0.12) | 4.98 (0.11) |

| GC | 4.00 (0.16) | 1.84 (0.14) | 4.64 (0.16) | 4.39 (0.14) | 4.99 (0.13) |

Note

- Ratings are based on a 6-point scale where 1 = unskillful and 6 = skillful; ND = no self-disclosure; Pt = patient; GC = genetic counselor.

The non-disclosure response with the highest mean ratings in both samples was a redirecting non-disclosure with a reassuring intention (This is a tough decision. Let's talk about the issues you're thinking about, so you can make the choice that is best for you and your family). The non-disclosure response with the lowest mean ratings in both samples was decline to disclose with a literal intention (This is a difficult question. I can't say what I would do).

7.1.2 Inferential analyses

A three-way mixed ANOVA assessed differences in skillfulness ratings for counselor non-disclosure responses as a function of sample (proxy patient, genetic counselor), response type (redirecting, declining), and response intentions (interpretive, literal, corrective, guiding, and reassuring).

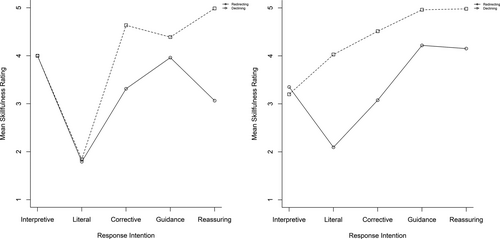

The ANOVA yielded a significant three-way interaction [F(4,720) = 21.16, p < .001,  = 0.10], as well as very strong main effects for response type [F(1,180) = 195.03, p < .001,

= 0.10], as well as very strong main effects for response type [F(1,180) = 195.03, p < .001,  = 0.52] and response intention [F(4,720) = 139.05, p < .001,

= 0.52] and response intention [F(4,720) = 139.05, p < .001,  = 0.44]. Full ANOVA results are presented in the Table S3. The three-way interaction is presented in Figure 2. The pattern of skillfulness ratings was different for genetic counselors and proxy patients. Genetic counselors had virtually identical skillfulness ratings for the interpretive and literal response intentions regardless of response type while they found corrective, guiding, and reassuring response intentions to be more skillful for redirecting non-disclosure responses than declining non-disclosure responses. The proxy patients had very similar skillfulness ratings for interpretive responses regardless of response type, and they rated the remaining response intentions higher for redirecting non-disclosure responses than for declining non-disclosures.

= 0.44]. Full ANOVA results are presented in the Table S3. The three-way interaction is presented in Figure 2. The pattern of skillfulness ratings was different for genetic counselors and proxy patients. Genetic counselors had virtually identical skillfulness ratings for the interpretive and literal response intentions regardless of response type while they found corrective, guiding, and reassuring response intentions to be more skillful for redirecting non-disclosure responses than declining non-disclosure responses. The proxy patients had very similar skillfulness ratings for interpretive responses regardless of response type, and they rated the remaining response intentions higher for redirecting non-disclosure responses than for declining non-disclosures.

Given the interaction is primarily ordinal and the very large effect size of the main effects of response type ( = 0.52) and intention (

= 0.52) and intention ( = 0.44) in both an absolute sense and relative to the effect size of the interaction (

= 0.44) in both an absolute sense and relative to the effect size of the interaction ( = 0.10), exploration of the post hoc tests for response type and intention is justified. Redirecting responses were rated as more skillful than declining responses (mean difference = 0.87, p<.001). Full results of the post hoc analyses for response intention are available in Table S4. There were no significant differences between the guiding or reassuring response intention skillfulness ratings (p = .89), and both were rated more skillful than interpretive, corrective, or literal intentions (all p < .001). There was no difference between interpretive and corrective response intentions (p = .12), and both were rated more skillful than a literal intention (both p < .001).

= 0.10), exploration of the post hoc tests for response type and intention is justified. Redirecting responses were rated as more skillful than declining responses (mean difference = 0.87, p<.001). Full results of the post hoc analyses for response intention are available in Table S4. There were no significant differences between the guiding or reassuring response intention skillfulness ratings (p = .89), and both were rated more skillful than interpretive, corrective, or literal intentions (all p < .001). There was no difference between interpretive and corrective response intentions (p = .12), and both were rated more skillful than a literal intention (both p < .001).

8 DISCUSSION OF STUDY 2 SKILLFULNESS RATINGS

Both genetic counselors and proxy patients rated reassuring non-disclosure responses as significantly more skillful than declining non-disclosures. The response with the highest mean ratings in both groups was a redirecting non-disclosure with a reassuring intention. As discussed in Study 1, there is a genetic counselor belief that some patients request self-disclosure because they want validation (Balcom et al., 2013; Thomas et al., 2006). A reassuring redirecting response may be viewed as skillful because it provides validation to patients, a finding that is consistent with psychotherapy literature on skillful non-disclosure responses (Hanson, 2005).

The redirecting and decline non-disclosures with a guiding intention received relatively high skillfulness ratings by genetic counselors and proxy patients. These findings support prior research suggesting that some genetic counseling patients are looking for guidance when they request self-disclosure (Balcom et al., 2013; Thomas et al., 2006). These non-disclosure responses may also empower and validate some patients to make their own decisions, which is a feature of skillful non-disclosure responses in psychotherapy (Hanson, 2005).

Both genetic counselors and proxy patients also gave relatively high skillfulness ratings to both the corrective redirecting and decline non-disclosures. Their ratings may be partially explained by prior research findings that skillful non-disclosures often explain the reason for non-disclosure (Balcom et al., 2013; Hanson, 2005). Both corrective responses in the present study contained an explanation for why the genetic counselor could not answer the request for self-disclosure.

Genetic counselors rated interpretive non-disclosure responses as higher in skill than proxy patients. Interpretive responses relate to REM goals that encourage patients to examine their emotions and consider new perspectives (McCarthy Veach et al., 2007). These goals may not be applicable to all patients, and some genetic counselors have commented that these goals can be either patient-dependent or inappropriate (Hartmann, Veach, MacFarlane, & LeRoy, 2015).

Both genetic counselors and proxy patients on average rated the literal declining non-disclosure as unskillful. However, proxy patients generally rated the literal redirecting non-disclosure as skillful while the genetic counselors did not. Literal responses take the patient's question at face value and provide a surface level answer. Some proxy patients may have preferred a surface level answer because they lacked a nuanced understanding of the hypothetical patient's underlying emotions. They may have rated the redirecting response more favorably because it offers to review and provide information about the patient's options. As such, the response reflects a key REM tenet of education (McCarthy Veach et al., 2007).

9 STUDY 1 AND 2 QUALITATIVE RESULTS: PARTICIPANT DESCRIPTIONS OF A SKILLFUL RESPONSE

Across both studies, participant descriptions of what made a response skillful were coded using Redlinger-Grosse et al.’s (2013) five categories of genetic counselor intentions: interpretive, reassuring, corrective, guiding, and literal. Thematic analysis yielded two additional categories: focus on patient and promotes autonomy. Answers that could not otherwise be classified were labeled miscellaneous. Miscellaneous answers often referenced counselor tone (e.g. described the response as polite) or sentence structure (e.g. the response uses patient words, is open-ended). Participant responses were often multifaceted and therefore classified within multiple categories. Table 6 contains definitions of the seven coding categories and verbatim examples. Frequencies of categories extracted from their open-ended comments are contained in Table S5.

| Category | Definition | Proxy Pt quote | GC quote |

|---|---|---|---|

| Corrective | Remind the patient her situation differs from the counselor's | ‘…it's a personal choice, and that what the counselor would do might not be the best choice for Katie’ | ‘reminds the patient that the decision is personal and unique to her own circumstances’ |

| Focus on Patient | Maintain focus of the conversation on the patient | ‘…makes it all about the patient, not about the counselor’ | ‘Focusing back to the needs of the patient’ |

| Guiding | Attempt to facilitate decision-making | ‘Gets her to clarify her concerns to move forward in decision making’ | ‘Facilitates decision making by weighing the patient's top priorities’ |

| Interpretive | Offer counselor insight into patient reasons for the question | ‘[tries] to get to the root of what is causing Katie's hesitancy’ | ‘Creating and expressing a ‘hunch’ about the situation/patient response’ |

| Literal | Take the question at ‘face value’ | ‘being truthful and explaining the science behind the amnio’ | ‘…outlines specifically what reasons to consider’ |

| Promotes Autonomy | Promote patient decision independent from the counselor opinion | ‘Offers help without giving a biased opinion’ | ‘Makes patient consider that her decision should not be influenced by others’ |

| Reassuring | Support or validate the patient | ‘alleviates her fear that she will make the wrong choice by assuring her there is no such thing’ | ‘normalizes her feelings and affirms that there is no wrong choice’ |

Prevalent categories for both samples were guiding (regarding decision-making) and reassuring (the patient). The corrective category (reminding the patient she and the counselor are different) was infrequent in both samples. There were also apparent differences between the samples. A greater percentage of genetic counselors mentioned focus on the patient, whereas a greater percentage of proxy patients mentioned promotes autonomy. There are striking differences for two categories. Interpretive (addressing underlying motivations for the patient's question) was one of the most prevalent categories for genetic counselors, but it was very low in frequency for proxy patients. The literal category (taking the patient's question at face value and responding accordingly) was somewhat common for proxy patients, but only two genetic counselors provided descriptions classified within this category.

10 OVERALL DISCUSSION

Overall, a majority of genetic counselors and proxy patients described skillful responses as those which provide reassurance/support and offer guidance. Very few participants described a skillful response as corrective. These results are fairly congruent with the Likert ratings of responses. In particular, responses with a guiding or reassuring intention generally received the highest skillfulness ratings in both studies.

Similar to differences between the samples’ skillfulness ratings, there were apparent differences between some of their descriptions of skillfulness. A large percentage of genetic counselors identified a skillful response as interpretive (exploring the patient's motivation for the self-disclosure request), and maintaining a focus on the patient. A focus on the patient is similar to previous findings that genetic counselors’ intend to keep attention on the patient regardless of whether they use self-disclosures or non-disclosures (cf. Redlinger-Grosse et al., 2013). This finding is also consistent with Hanson’s (2005) conclusion that skillful therapist disclosures and non-disclosures maintain a client focus. A greater percentage of proxy patients described a skillful response as promoting autonomy, and as being literal (answering patient question at face value).

Many participants in both groups commented that skillful responses reflected the genetic counselor's competency and/or genuineness. Perceptions of counselor genuineness and competency may be a by-product of response skillfulness, as some psychotherapy studies have shown that skillful responses can increase client trust, clinician likability, and perceived competence (Audet, 2011; Hanson, 2005).

The present findings suggest that although genetic counselors and proxy patients generally appear to be ‘on the same page’ regarding perceived response skillfulness (especially for guiding and reassuring responses), their views sometimes diverge. Importantly, responses genetic counselors regard as skillful may not always align with patient perceptions and may even create misunderstanding regarding the counselor's intention. Variations in perceptions may be partially explained by the limited content/context available in the hypothetical scenario. This factor likely would affect proxy patients to a greater extent than experienced genetic counselors. The variability in proxy patients’ comments highlights the importance of considering individual differences in patient reactions to genetic counselor statements.

10.1 Research limitations

Several factors may limit the generalizability of the present findings to actual genetic counseling sessions and different practice specialties. This study used a hypothetical prenatal genetic counseling scenario and non-random samples of genetic counselors and proxy patients. The use of written as opposed to audio counselor responses poses further limitations. For instance, a number of participants commented that they tried to interpret tone from the written responses. The counselor statements, although derived from the Redlinger-Grosse et al.’s (2013) findings, do not capture all possible responses. To portray the most common genetic counselor responses found by Redlinger-Grosse et al. (2013), some of the non-disclosures included self-referent pronouns (e.g. I can't say, I want to help you). This may have confounded results if participants considered these statements as self-disclosure. Finally, a single response does not capture a genetic counselor's overall skillfulness, and a skillful response may or may not be a helpful response.

The design of this research cannot completely rule out order effects, as the order of presentation of response type and response intention was not counterbalanced to ensure each permutation of response statements was presented the same number of times. Because each element was randomized per person; however, significant order effects are deemed highly unlikely. Given this study is the first to examine the skillfulness of genetic counselor responses in this context, replication is needed before one can confidently implement practice changes, and we recommend future studies more tightly control order effects (e.g. Latin Square design) to completely rule out this possible confound. Each response should also be presented on its own page of the survey without allowing participants to navigate to prior pages to eliminate the possibility of their deciding on their own order.

10.2 Practice implications

The results of this research suggest that response skillfulness involves a complex interplay among response type, counselor intention, and who is judging the skillfulness. Although both disclosing and non-disclosing responses conveying guidance and reassurance were generally viewed as skillful, the wide range of participants’ responses, particularly for proxy patients, illustrate the importance of individual differences. Genetic counselors and proxy patients did not always agree about the skillfulness of certain responses. Particularly noteworthy, a number of counselors favored interpretive responses, whereas a number of proxy patients preferred literal responses. Such differences indicate the importance of recognizing and responding to diverse patients’ needs, and/or the need to clarify for patients the genetic counselor's role in shared decision-making. These actions align with goals and tenets of the REM of genetic counseling practice (McCarthy Veach et al., 2007); in particular, goals involving the facilitation of decision-making and empowering patients, and tenets concerning the importance of relationship, individual attributes, and patient emotions.

The present findings and extant genetic counseling literature (e.g. Balcom et al., 2013; McCarthy Veach et al., 2018) suggest a few approaches when a prenatal patient asks the counselor what s/he would do: Assess patients’ needs, that is, either use your intuition to discern what they are seeking (e.g. guidance, support), or ask them to explain what they hope to gain by their question. This information may help you decide how to respond to their self-disclosure request. Be mindful, however, that some patients may be unable to explain their rationale and/or prefer not to be queried this way; clearly, they should not be pressed to provide a reason. Therefore, relying on your intuition rather than asking directly, may be a less risky strategy.

In the present study, some proxy patients noted that perceived counselor tone and acknowledgment of the self-disclosure request question played a role in their skillfulness ratings. Taking care to respond in a way that indicates respect (polite tone, acknowledges the question) may enhance the skillfulness of your response. For example, when using a redirecting non-disclosure response, first acknowledge the patient has asked a question and then redirect (e.g., ‘You asked me what I would do. I can see how difficult this decision is for you. Perhaps we can revisit the options’). Explain the reasons for your response (Balcom et al., 2013; Hanson, 2005), especially an interpretive response, and/or when declining to disclose, as this may prevent patient misperceptions and increase patient receptivity.

Finally, corrective responses received low ratings by both proxy patients and genetic counselors. These findings suggest you should avoid corrective responses unless some special circumstance makes them seem necessary. For instance, a patient might repeatedly ask you to tell them what to do. You may need to re-explain this is not part of your role and add a supportive statement that you would like to work with them to figure out what they wish to do.

10.3 Research recommendations

Further research on the skillfulness of counselor self-disclosure and non-disclosure responses in genetic counseling is needed. Designs that more closely reflect actual sessions such as video-recorded interactions (cf. Volz et al., 2018) would allow for assessment of the impact of non-verbals such as tone on perceptions of skillfulness. Future research should also investigate potential demographic and cultural differences in perceptions of skillfulness, especially among patients. Studies of other genetic counseling specialties and involving other types of self-disclosure requests would help to replicate and extend the present results. Further research could help to discern reasons genetic counselors’ perceptions do not always align with patients’ perceptions. Finally, studies are needed to investigate the extent to which skillful counselor responses lead to desired processes and outcomes in genetic counseling.

11 CONCLUSION

The present research helps to empirically define ‘skillful’ counselor responses to patient requests for self-disclosure. Genetic counselors and proxy patients commonly perceived skillful responses as providing guidance and reassurance. Responses generally perceived as less skillful were corrective (reminding the patient that they are different from the genetic counselor). Response intentions interacted with response types to affect participants’ perceptions, and genetic counselors and proxy patients differed in some of their perceptions of skillfulness. Variability of perceptions within the proxy patient sample indicates the need for genetic counselors to consider patients’ characteristics, the genetic counseling context, and genetic counseling goals, to decide how best to respond to requests for self-disclosure.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

V Greve: performed data analysis, interpreted data, wrote manuscript, helped to edit and evaluate manuscript, and acted as corresponding author. P McCarthy Veach: supervised development of work, performed data analysis, interpreted data, wrote manuscript, and helped to edit and evaluate manuscript. BS LeRoy: supervised development of work and helped to edit and evaluate manuscript. IM MacFarlane: performed statistical analysis, interpreted data, and helped to edit and evaluate manuscript. K Redlinger-Grosse: supervised development of work, performed data analysis, interpreted data, and helped to edit and evaluate manuscript.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This study was conducted by Veronica Greve as part of her training to fulfill a master's degree requirement. This project was funded in part by the National Society of Genetic Counselor's Prenatal Special Interest Group's 2017 Spring Grant.

COMPLIANCE WITH ETHICAL STANDARDS

Conflict of interest

Authors V Greve, P McCarthy Veach, BS LeRoy, IM MacFarlane, and K Redlinger-Grosse declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Human studies and informed consent

This study was reviewed and determined to be exempt from review by the University of Minnesota institutional review board. Informed consent was obtain from all participants and no identifying information was collected.

Animal studies

No non-human animal studies were performed by the authors for this article.